Chapter 3

Examining Contribution Margin

In This Chapter

![]() Figuring contribution margin

Figuring contribution margin

![]() Meeting income goals with cost-volume-profit analysis

Meeting income goals with cost-volume-profit analysis

![]() Analyzing your break-even point, target profit, and margin of safety

Analyzing your break-even point, target profit, and margin of safety

![]() Exploring operating leverage

Exploring operating leverage

When you have to make a business decision about what to sell, how much of it to sell, or how much to charge, you first need to understand how your decision is likely to affect net income — your profit. Suppose you sell one refrigerator for $999.95. How does that sale affect your net income? Now suppose you sell 1,000 of the same make and model at this price. How does that sales volume affect net income?

Contribution margin simplifies these decisions. In this chapter, you find out how to calculate contribution margin and how to apply it to different business decisions, using both graphs and formulas. You also find out how to prepare something called a cost-volume-profit analysis, which explains how the number of products sold affects profits. And you discover how to prepare a break-even analysis, which indicates exactly how many products you must sell in order to break even and start earning a profit.

Suppose you set a target profit — a goal for net income this period. This chapter shows you how to estimate the number of units you need to sell in order to meet your target profit. It also explains how to measure something called margin of safety, or how many sales you can afford to lose before your profitability drops to zero. Finally, this chapter explains and demonstrates operating leverage, which measures a company's riskiness.

Computing Contribution Margin

Contribution margin = Sales – Variable costs

For example, if you sell a gadget for $10 and its variable cost is $6, the contribution margin for the sale is $10 – $6 = $4. Selling this gadget increases your profit by $4, before considering fixed costs. Your contribution margin less fixed costs equals your profit.

You can calculate contribution margin in three forms, as discussed in the following sections: in total, per unit, or as a ratio.

Contribution margin, in any of its forms, explains how different factors in the company — sales price, sales volume, variable costs, and fixed costs — interact. This understanding helps you make better decisions when planning sales and costs.

Figuring total contribution margin

Total contribution margin measures the amount of contribution margin earned by the company as a whole. You calculate it by using this formula:

Total contribution margin = Total sales – Total variable costs

To determine overall profitability, subtract total fixed costs from total contribution margin. Net income equals the excess of contribution margin over fixed costs.

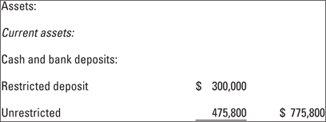

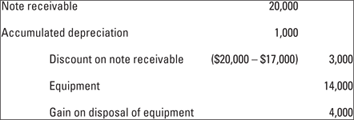

You can use total contribution margin to create something called a contribution margin income statement. This document differs from a multi-step income statement (shown in Figure 3-1), where you first subtract cost of goods sold from sales and then subtract selling, general, and administrative costs.

©John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Figure 3-1: Multi-step income statement.

A contribution margin income statement first subtracts the variable costs and then subtracts fixed costs, as shown in Figure 3-2. Here, variable costs include variable costs of both manufacturing and selling. Likewise, fixed costs include more manufacturing and selling costs.

©John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Figure 3-2: Contribution margin income statement.

The contribution margin income statement makes understanding cost behavior and the way sales will affect profitability easier. In Figure 3-2, the company earns $1,000 in sales, $400 of which goes toward variable costs. This scenario results in $600 of contribution margin.

These amounts — sales, variable costs, and contribution margin — change in proportion to each other. If sales increase by 10 percent, then variable costs and contribution margin also increase by 10 percent; $1,100 in sales increases variable costs to $440 and contribution margin to $660. On the other hand, fixed costs always remain the same: The $300 in fixed costs is $300 regardless of any increase or decrease in sales and contribution margin.

Calculating contribution margin per unit

Contribution margin per unit = Sales price per unit – Variable costs per unit

Say a company sells a single gadget for $100, and the variable cost of making the gadget is $40. Contribution margin per unit on this gadget equals $100 – $40 = $60. Therefore, selling the gadget increases net income by $60, assuming no change in fixed costs.

Increasing the sales price doesn't affect variable costs because the number of units manufactured, not the sales price, is what usually drives variable manufacturing costs. Therefore, if the gadget company raises its sales price to $105, the variable cost of making the gadget remains at $40, and the contribution per unit increases to $105 – $40 = $65 per unit. The $5 increase in sales price goes straight to the bottom line as net income. Again, this assumes that fixed costs don't change.

Working out contribution margin ratio

- Contribution margin ratio = Total contribution margin ÷ Total sales

- or

- Contribution margin ratio = Contribution margin per unit ÷ Sales price per unit

Suppose a gadget selling for $100 per unit brings in $40 per unit of contribution margin. Its contribution margin ratio is 40 percent:

Contribution margin ratio = $40 ÷ $100 = 0.40 or 40%

To find out how sales affect net income, multiply the contribution margin ratio by the amount of sales. In this example, $1,000 in gadget sales increases net income by $1,000 × 0.40 = $400 (before considering fixed costs).

Preparing a Cost-Volume-Profit Analysis

Contribution margin indicates how sales affects profitability. When running a business, a decision-maker needs to consider how four different factors affect net income:

- Sales price

- Sales volume

- Variable cost

- Fixed cost

Cost-volume-profit analysis helps you understand different ways to meet your net income goals. The following sections explain cost-volume-profit analysis by using graphical and formula techniques. These sections pay special attention to computing net income based on different measures of contribution margin: total contribution margin, contribution margin per unit, and the contribution margin ratio.

Drafting a cost-volume-profit graph

Figure 3-3 visually describes the relationship among cost, volume, and profit for a company called Pemulis Basketballs. It sells its basketballs for $15 per basketball. The variable cost of the basketballs is $6. Pemulis has total fixed costs of $300 per year.

©John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Figure 3-3: Cost-volume-profit graph.

In this figure, the fixed costs of $300 are represented by a horizontal line because regardless of the sales volume, fixed costs stay the same. Total variable costs are a diagonal line, starting at the origin (the point in the lower-left corner of the graph where sales are zero). Total costs (the sum of total variable costs and total fixed costs) are a diagonal line starting at the $300 mark because when the company makes and sells zero units, total costs equal the fixed costs of $300. Total costs then increase with volume. Finally, total sales forms a diagonal line starting at the origin and increasing with sales volume.

Figure 3-4 shows when the company will earn net income or incur a loss. When the sales curve exceeds total costs, the company earns net income (represented by the shaded right side of the X in Figure 3-4). However, if total sales are too low to exceed total costs, then the company incurs a net loss (the shaded left side of the X). The higher the sales volume — that is, the more sales volume moves to the right of the graph — the higher the company's net income.

©John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Figure 3-4: Identifying net income and loss in a cost-volume-profit graph.

Dropping numbers into the chart shows exactly how much income can be earned at different sales levels. Assuming Pemulis has a sales price of $15 per unit, a variable cost per unit of $6, and total fixed costs of $300, what happens if Pemulis sells 60 basketballs? Total sales come to 60 units × $15 = $900. Total variable costs multiply to 60 units × $6 = $360. Add these total variable costs to total fixed costs of $300 to get total costs of $660.

Figure 3-5 illustrates these amounts. Total sales of $900 sits on the Total sales line. Total costs of $660 sits on the Total cost line. The difference between these amounts of $240 represents the net income from selling 60 units.

©John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Figure 3-5: Applying a cost-volume-profit graph to a specific case.

Trying out the total contribution margin formula

Net income = Total contribution margin – Fixed costs

Assume that Pemulis Basketballs sells 60 units for $15 each for total sales of $900 (see the preceding section for more on the origins of this example). The variable cost of each unit is $6 (so total variable costs come to $6 × 60 = $360), and total fixed costs are $300. Using the contribution margin approach, you can find the net income in two easy steps:

- Calculate total contribution margin.

Use the formula provided earlier in the chapter to compute total contribution margin, subtracting total variable costs from total sales:

Total contribution margin = Total sales – Total variable costs = (60 × $15) – (60 × $6) = $900 – $360 = $540

This total contribution margin figure indicates that selling 60 units increases net income by $540 (before considering fixed costs).

- To calculate net income, subtract the fixed costs from the total contribution margin.

Just plug in the numbers from Step 1:

Net income = Total contribution margin – Fixed costs = $540 – $300 = $240

Subtracting fixed costs of $300 from total contribution margin of $540 gives you net income of $240.

Practicing the contribution margin per unit formula

If you know the contribution margin per unit (see “Calculating contribution margin per unit” earlier in this chapter), the following approach lets you use that information to compute net income. Here's the basic formula equating net income with contribution margin per unit:

Net income = (Sales volume × Contribution margin per unit) – Fixed costs

Say Pemulis Basketballs now wants to use this formula. It can simply plug in the numbers — 60 units sold for $15 each, variable cost of $6 per unit, fixed costs of $300 — and solve. First compute the contribution margin per unit:

Contribution margin per unit = Sales price per unit – Variable costs per unit = $15 – $6 = $9

Next, plug contribution margin per unit into the net income formula to figure out net income:

Net income = (Sales volume × Contribution margin per unit) – Fixed costs = (60 × $9) – $300 = $540 – $300 = $240

Eyeing the contribution margin ratio formula

If you want to estimate net income but don't know total contribution margin and can't find out the contribution margin per unit, you can use the contribution margin ratio to compute net income.

Contribution margin ratio = Total contribution margin ÷ Total sales = Contribution margin per unit ÷ Sales price per unit = $540 ÷ $900 = 0.60 = 60%

This means that 60 cents of every sales dollar increases net income, after considering fixed costs. After you know the contribution margin ratio, you're ready for the net income formula:

Net income = (Sales volume in units × Contribution margin per unit) – Fixed costs

To calculate net income for the earlier example company, plug the contribution margin ratio of 60 percent into the formula:

Net income = (Sales volume in units × Contribution margin per unit) – Fixed costs = ($900 × 0.60) – $300 = $540 – $300 = $240

Generating a Break-Even Analysis

How much do you need to sell in order to break even? The break-even point (BE) is the amount of sales needed to earn zero profit — enough sales to avoid a loss, but insufficient sales to earn a profit. This section shows you a couple of different ways — graphs and formulas — to locate your break-even point.

Plotting the break-even point

In a cost-volume-profit graph, the break-even point is the sales volume where the total sales line intersects with the total costs line. This sales volume is the point at which total sales equals total costs.

Suppose that, as with the basketball example earlier in the chapter, a company sells its products for $15 each, with variable costs of $6 per unit and total fixed costs of $300. The graph in Figure 3-6 indicates that the company's break-even point occurs when the company sells 34 units.

©John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Figure 3-6: Plotting the break-even point.

Using the formula approach

When you need to solve actual problems, drawing graphs isn't always practical. For a quicker approach, you want to rely on the three formulas that use contribution margin to measure net income. (See “Preparing a Cost-Volume-Profit Analysis” earlier in the chapter.)

The break-even point is where net income is zero, so just set net income equal to zero, plug whatever given information you have into one of the equations, and then solve for sales or sales volume. Better yet: At the break-even point, total contribution margin equals fixed costs.

Suppose a company has $30,000 in fixed costs. How much total contribution margin does it have to generate in order to break even?

- Net income = Total contribution margin – Fixed costs

- 0 = Total contribution marginBE – Fixed costs

- 0 = Total contribution marginBE – $30,000

- $30,000 = Total contribution marginBE

Here, too, at the break-even point, total contribution margin equals fixed costs of $30,000. Now suppose a company has contribution margin per unit of $6 and fixed costs of $600. What's the break-even point in units?

- Net income = (Sales volume × Contribution margin per unit) – Fixed costs

- 0 = (Sales volumeBE × Contribution margin per unit) – Fixed costs

- 0 = (Sales volumeBE × $6) – $600

- $600 = Sales volumeBE × $6

- $600 ÷ $6 = 100 units

Another company has a contribution margin ratio of 40 percent and fixed costs of $1,000. Sales price is $1 per unit. What's the break-even point in dollars?

Net income = (Sales × Contribution margin ratio) – Fixed costs

- 0 = (SalesBE × Contribution margin ratio) – Fixed costs

- 0 = (SalesBE × 0.40) – $1,000

- $1,000 = SalesBE × 0.40

- $1,000 ÷ 0.40 = SalesBE

- $2,500 = SalesBE

Shooting for Target Profit

If you've set a specific goal for net income, contribution margin analysis can help you figure out the needed sales. This goal for net income is called target profit.

- Net income = Total contribution margin – Fixed costs

- $20,000 = Total contribution marginTarget – $10,000

- $30,000 = Total contribution marginTarget

Total contribution margin of $30,000 will result in $20,000 worth of net income. Now suppose a company has set its target profit for $2,000, earns contribution margin per unit of $5, and incurs fixed costs of $500. How many units must the company sell?

- Net income = (Sales volume × Contribution margin per unit) – Fixed costs

- $2,000 = (Sales volumeTarget × Contribution margin per unit) – Fixed costs

- $2,000 = (Sales volumeTarget × $5) – $500

- $2,500 = Sales volumeTarget × $5

- $2,500 ÷ $5 = Sales volumeTarget

- 500 units = Sales volumeTarget

If the company wants to earn $2,000 in profit, it needs to sell 500 units. Consider another company with a contribution margin ratio of 40 percent and fixed costs of $1,000. The company is looking to earn $600 in net income. How much does that company need in sales?

- Net income = (Sales × Contribution margin ratio) – Fixed costs

- $600 = (SalesTarget × Contribution margin ratio) – Fixed costs

- $600 = (SalesTarget × 0.40) – $1,000

- $1,600 = SalesTarget × 0.40

- $1,600 ÷ 0.40 = SalesTarget

- $4,000 = SalesTarget

Observing Margin of Safety

Margin of safety is the difference between your actual or expected profitability and the break-even point. It measures how much breathing room you have — how much you can afford to lose in sales before your net income drops to zero. When budgeting, compute the margin of safety as the difference between budgeted sales and the break-even point. Doing so will help you understand the likelihood of incurring a loss. Turn to Book VI, Chapters 4 and 5 for more about budgeting.

Using a graph to depict margin of safety

Figure 3-7 shows you how to visualize margin of safety with a graph. In this example, margin of safety is the difference between current or projected sales volume of 60 units and break-even sales volume of 34 units, which is 26 units. Sales would have to drop by 26 units for existing net income of $240 to completely dry up.

©John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Figure 3-7: Graphing margin of safety.

Calculating the margin of safety

To compute margin of safety directly, without drawing pictures, first calculate the break-even point and then subtract it from actual or projected sales. You can use dollars or units:

- Margin of safety (in dollars) = SalesActual – SalesBE

- Margin of safety (in units) = Unit salesActual – Unit salesBE

For guidance on finding the break-even point, check out the earlier section “Generating a Break-Even Analysis.”

Taking Advantage of Operating Leverage

Operating leverage is typically driven by a company's blend of fixed and variable costs. The larger the proportion of fixed costs to variable costs, the greater the operating leverage. For example, airlines are notorious for their high fixed costs. Airlines’ highest costs are typically depreciation, jet fuel, and labor — all costs that are fixed with respect to the number of passengers on each flight. Their most significant variable cost is probably just the cost of the airline food, which, judging from some recent flights couldn't possibly be very much. Therefore, airlines have ridiculously high operating leverage and unspeakably low variable costs. A small drop in the number of passenger-miles can have a dreadful effect on an airline's profitability.

Graphing operating leverage

In a cost-volume-profit graph (see Figure 3-3 earlier in the chapter), operating leverage corresponds to the slope of the total costs line. The more horizontal the slope of this line, the greater the operating leverage. Figure 3-8 compares the operating leverage for two different entities, Safe Co., which has lower operating leverage, and Risky Co., which has higher operating leverage.

©John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Figure 3-8: How operating leverage increases risk.

In this example, Risky Co. has higher fixed costs and lower variable costs per unit than Safe Co. Therefore Risky's total cost line is more horizontal than Safe's total cost line. Accordingly, Risky has the potential to earn much higher income with the same sales volume than Safe does. Because its fixed costs are so high, Risky also has the potential to incur greater losses than Safe does.

Looking at the operating leverage formula

The formula for operating leverage is

Operating leverage = Total contribution margin ÷ Net income

Suppose that Safe Co. and Risky Co. each earn sales of $400 on 50 units. Assume that on these sales, Safe Co. has $150 in contribution margin and Risky has $300 in contribution margin. Safe Co. has fixed costs of $50, while Risky Co. has fixed costs of $200. Safe's net income comes to $100 ($150 – $50). At this volume level, Risky's net income also works out to be $100. Here's the math:

- Operating leverage = Total contribution margin ÷ Net income

- Operating leverageSafe Co. = $150 ÷ $100 = 1.5

- Operating leverageRisky = $300 ÷ $100 = 3.0

According to these measures, Risky Co. has twice the operating leverage of Safe Co. Although a 10-percent increase in sales boosts Safe Co.'s net income by 15 percent, a similar 10-percent increase in sales for Risky Co. increases that company's net income by 30 percent!

That said, high operating leverage can work against you. For Safe Co., a 10-percent decrease in sales cuts income by 15 percent; for Risky, a 10-percent decrease in sales reduces net income by 30 percent.

Contribution margin measures how sales affects net income or profits. To compute contribution margin, subtract variable costs of a sale from the amount of the sale itself:

Contribution margin measures how sales affects net income or profits. To compute contribution margin, subtract variable costs of a sale from the amount of the sale itself: When computing contribution margin, subtract all variable costs, including variable manufacturing costs and variable selling, general, and administrative costs. Don't subtract any fixed costs. You compute gross profit by subtracting cost of goods sold from sales. Because cost of goods sold usually includes a mix of fixed and variable costs, gross profit doesn't equal contribution margin.

When computing contribution margin, subtract all variable costs, including variable manufacturing costs and variable selling, general, and administrative costs. Don't subtract any fixed costs. You compute gross profit by subtracting cost of goods sold from sales. Because cost of goods sold usually includes a mix of fixed and variable costs, gross profit doesn't equal contribution margin. The graphs provide a helpful way to visualize the relationship among cost, volume, and profit. However, when solving problems, you'll find that plugging numbers into formulas is much quicker and easier.

The graphs provide a helpful way to visualize the relationship among cost, volume, and profit. However, when solving problems, you'll find that plugging numbers into formulas is much quicker and easier.