Chapter 1

Identifying Costs and Matching Costs with Revenue

In This Chapter

![]() Knowing the ins and outs of costs and expenses

Knowing the ins and outs of costs and expenses

![]() Understanding the difference between product and period costs

Understanding the difference between product and period costs

![]() Figuring out which costs to depreciate

Figuring out which costs to depreciate

![]() Mulling over revenue recognition

Mulling over revenue recognition

This chapter is your introduction to a company's tangible assets, which you can touch and feel — they have a physical presence. Tangible assets, also called fixed assets, include property, plant, and equipment (PP&E). Many fixed assets are used for years, and a company relies on a mysterious accounting tool called depreciation to keep its financial statements in line with the reality of how long those assets stay in use.

If you read this entire chapter, depreciation won't seem so mysterious anymore. This chapter helps you understand what depreciation is and how it connects a business's costs to its expenses. (Yes, costs and expenses are two different things in the business world.) This chapter also walks you through the information you find in a schedule of depreciation.

Because you match expenses with revenue, this chapter wraps up with a discussion of revenue recognition — the event or transaction that determines when revenue is posted to your accounting records.

Defining Costs and Expenses in the Business World

In the world of business, costs aren't the same as expenses. Note this process:

- When a business incurs a cost, it exchanges a resource (usually cash or a promise to pay cash in the future) to purchase a good or service that enables the company to generate revenue.

- Later, when the asset is used to create a product or service, the cost of the asset is converted into an expense.

- When the product or service is sold, the company generates revenue. The revenue is matched with the expenses incurred to generate the revenue. Businesses use this matching principle to calculate the profit or loss on the transaction.

Here's an example of a common business transaction that demonstrates the process:

Suppose you're the manager of the women's apparel department of a major manufacturer. You're expanding the department to add a new line of formal garments. You need to purchase five new sewing machines, which for this type of business are fixed assets.

When you buy the sewing machines, the price you pay (or promise to pay) is a cost. Then, as you use the sewing machines in the normal activity of your business, you depreciate them: You reclassify the cost of buying the asset to an expense. So the resources you use to purchase the sewing machines move from the balance sheet (cost) to the income statement (expense).

Your income statement shows revenue and expenses. The difference between those two numbers is the company's net income (when revenue is more than expense) or net loss (when expenses are higher than revenue).

Still wondering what the big deal is with accountants having to depreciate fixed assets? Well, the process ties back to the matching principle, discussed in the next section.

Satisfying the Matching Principle

In accounting, every transaction you work with has to satisfy the matching principle (see Book I, Chapter 4). You have to associate all revenue earned during the accounting period to all expenses you incur to produce that revenue. The idea is that the expenses are matched with the revenue — regardless of when the expense occurs.

Continuing with the sewing machine example from the previous section, suppose the life of the sewing machine — the average amount of time the company knows it can use the sewing machine before having to replace it — is five years. The average cost of a commercial sewing machine is $1,500. If the company expenses the entire purchase price (cost) of $1,500 in the year of purchase, the net income for year one is understated and the net income for the next four years is overstated.

Why? Because although the company laid out $1,500 in year one for a machine, the company anticipates using the machine for another four years. So to truly match the sales the company generates from garments made by using the sewing machine, the cost of the machine has to be allocated over each of the years it will be used to crank out those garments for sale.

Identifying Product and Period Costs

The way a company classifies a cost depends on the category the cost falls into. Using generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP) as explained in Book IV, Chapter 1, business costs fall into the two general categories in the following list:

- Product costs: Any costs that relate to manufacturing or merchandising an item for sale to customers. A common example is inventory (see Chapter 2), which reflects costs a manufacturing company incurs when buying the raw materials it needs to make a product. For a merchandiser (retailer), the cost of inventory is what it pays to buy the finished goods from the manufacturer.

- Period costs: Costs that, although necessary to keep the business's doors open, don't tie back to any specific item the company sells. You can also think of period costs as costs you incur due to the passage of time, such as depreciation, rent, interest on a loan, and insurance premiums.

Discovering Which Costs Are Depreciated

When a company purchases a fixed asset (see Book IV, Chapter 3), such as a computer or machine, the cost of the asset is spread over its useful life, which may be years after the purchase. Therefore, depreciation is a period cost: As time passes, the fixed asset is used to generate revenue. The cost of the fixed asset is converted into an expense.

Your next question may be: “Which costs associated with purchasing a fixed asset do you add together when figuring up the entire cost? Just the purchase price? Purchase price plus tax and shipping? Other costs?”

For example, a company makes pencils and buys a new machine to automatically separate and shrink-wrap ten pencils into salable units. Various costs of the machine may include the purchase price, sales tax, freight-in, and assembly of the shrink-wrapping machine on the factory floor. (Freight-in is the buyer's cost to get the machine from the seller to the buyer.)

Handling real property depreciation

Now, what about real property — land and buildings? Both are clearly fixed assets, but the cost of the land a building sits on isn't depreciated and has to be separated from the cost of the building. Your financial statements will list land and building as two separate line items on the balance sheet. Why? The answer is that GAAP mandates that separation — no ifs, ands, or buts about it.

So, if a company pays $250,000 to purchase a building to manufacture its pencils and the purchase price is allocated 90 percent to building and 10 percent to land, how much of the purchase price is spread out over the useful life of the building? Your answer is: $250,000 × 0.90 = $225,000.

Allocating costs between land and buildings

Frequently, a company pays one price for both a building and the land that the building sits on. Figuring out the allocation of costs between land and building is a common challenge. The best approach is to have an appraisal done during the purchasing process.

An appraisal occurs when a licensed professional determines the value of real property. If you've ever purchased a home and applied for a mortgage, you're probably familiar with property appraisals. Basically, the appraisal provides assurance to the mortgage company that you're not borrowing more than the property is worth.

Even if a business doesn't have to secure a mortgage to purchase a real property asset, it still gets an appraisal to make sure it's not overpaying for the property. Alternatively, the county property tax records may show an allocation of costs to land. However, that allocation is just for property tax purposes; it may not be materially correct for depreciation purposes. Just remember to subtract land cost from the total before calculating real property depreciation (depreciation on just the building).

If a business purchases a piece of raw land and constructs its own building, the accounting issue is more straightforward, because you have a sales price for the land and construction costs for the building.

Expensing repairs and maintenance

Preventative repair and maintenance costs are expensed in the period in which they're incurred. For example, on June 14, a florist business has the oil changed and purchases new tires for the flower delivery van. The cost of the oil change and tires goes on the income statement as an operating expense for the month of June.

The next month, the delivery van's transmission goes completely out, stranding the driver and flowers at the side of the road. Rebuilding the transmission significantly increases the useful life of the delivery van, so you have to add the cost of the new transmission to the net book value of the van on the balance sheet. Net book value (or book value for short) is the difference between the cost of the fixed asset and its accumulated depreciation at any given time.

Preparing a Depreciation Schedule

Book III, Chapter 1 explains the different methods a business can use to calculate depreciation and how the methods compare to each other. A company may use different depreciation methods for different types of assets.

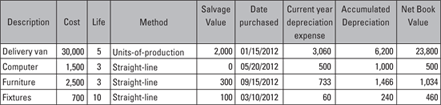

All businesses keep a depreciation schedule for their assets showing all the relevant details about each asset. Here is the basic information that shows up on a depreciation schedule:

- Description: The type of asset and any other identifying information about the fixed asset. For a truck, the description may include the make and model of the truck and its license plate number.

- Cost: The purchase price of the asset plus any other spending that should be added to the asset's cost. See “Discovering Which Costs Are Depreciated,” earlier in this chapter for an explanation of other costs that are included with the purchase price. Although most additions to purchase price take place when the company acquires the asset, the fixed asset cost can be added to after the fact if material renovations are performed. (Think about the truck transmission example from the earlier section “Expensing repairs and maintenance.”)

- Life: How long the company estimates it will use the fixed asset.

- Method: The method of depreciation the company uses for the fixed asset.

- Salvage value: The estimated value of the fixed asset when the company gets rid of or replaces it.

- Date purchased: The day the asset was purchased.

- Current depreciation: The depreciation expense booked in the current period.

- Accumulated depreciation: The total amount of depreciation expensed from the day the company placed the fixed asset in service to the date of the financial report.

- Net book value: The difference between the fixed asset cost and its accumulated depreciation.

Depending on the size of the company, the depreciation schedule may also have the fixed asset's identifying number, the location where the fixed asset is kept, property tax information, and many more facts about the asset.

Having a nicely organized depreciation schedule allows the company to keep at its fingertips a summary of activity for each fixed asset. Check out Figure 1-1 to see the basic organization for a depreciation schedule.

©John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Figure 1-1: Example of a depreciation schedule.

Deciding When to Recognize Revenue

The matching principle requires that you match costs incurred with the revenue a company generates. Previously in this chapter, you explore the costs side of the matching principle. You wrap up this chapter by considering the revenue side of the matching principle.

Going over the revenue recognition principle

The revenue recognition principle, first mentioned in Book I, Chapter 4, requires that, if you use the accrual basis of accounting, you recognize revenue by using these two criteria:

- Revenue is recorded when it has been earned

- Revenue is considered earned when the revenue generation process is substantially complete

Generally, the revenue generation process is complete when you deliver your product or service. So, when the clothing store receives jeans from the manufacturer, the company that produced the jeans should recognize revenue. If you're a tax accountant, you recognize revenue when you deliver the completed tax return to the client.

Recognizing revenue and cash flow

With accrual accounting, you can recognize revenue prior to receiving any payment from the client. A company recognizes revenue as soon as it delivers the goods or services.

For businesses that use accrual accounting, revenue recognized for the month may be very different from cash inflows for sales for the same period. Specifically, the increase in cash may not equal sales for the month. (See Book V, Chapter 2 for more about cash flows.)

A business using cash-basis accounting recognizes revenue when the cash is received from the client. (See Book I, Chapter 4 for more about the difference between cash- and accrual-basis accounting.) If you review the checkbook of a cash-basis company, the deposits for the month will match the revenue for the month. Most businesses, however, use the accrual-basis of accounting.

Except for the allocation of cost between land and buildings (see the section, “

Except for the allocation of cost between land and buildings (see the section, “