Ambiguity and Sentence Position: An Experimental Case Study on Manner Adverbs91

Abstract: Wasow (this volume) looks at ambiguity from the perspective of language production and concludes that speakers disobey the principle ‘Avoid ambiguity’ on many occasions. This paper looks at ambiguity from the perspective of language comprehension. The question is whether readers use specific information, namely the position of a word in a sentence for disambiguation. I will present an experimental study on ambiguous adverbs in German. The aim of the study is to differentiate between two approaches to position-driven differences in adverb interpretation and to show that experimental data have an important share in investigating ambiguity.

1 Introduction

In his article “Ambiguity Avoidance is Overrated”, Wasow (this volume) reports a number of studies from language production that present evidence against ‘Avoid ambiguity’ which is a sub-principle of the Gricean Maxim of Manner: Speakers do not stick to this principle on many occasions. The present study looks at ambiguity from another perspective, namely that of language comprehension. The question to be answered is whether readers use syntactic position information for the interpretation of ambiguous words. The linguistic phenomenon under consideration is ambiguous adverbials. One example of ambiguity in adverbs is given by Wasow (example (6b), repeated here as (1)).

(1) Pat frankly criticized our proposal.

Frankness can either be attributed to Pat or to the speaker’s description of what Pat did.

The present study will focus on German adverbs like sicher which has either a manner reading (‘confident’) or can be interpreted as speaker-oriented (‘certainly’).

Wasow points to the fact, that there is no diachronic evidence that ambiguity avoidance directs language change. The example above even shows that language change creates ambiguity. In earlier stages, sicher had the manner reading only. The speaker-oriented reading evolved later on (Axel-Tober & Featherston 2013; for the emergence of ‘subjective’ meanings from descriptive meanings in English, see e.g., Traugott 1982). In today’s German both readings are available.

The first aim of my study is to find out whether readers use the syntactic position of these adverbs for disambiguation. Furthermore, I would like to know whether the two readings are equally available or whether there is a preference for one of the two interpretations. The second aim is to differentiate between two accounts of these position-driven interpretation differences: the lexical approach, which assumes two different lexical entries, and the scope approach, which explains the two readings in terms of differences in scope taking.

First, I will give you a short overview of the psycholinguistic studies relevant for the phenomenon under investigation. The second part introduces the two approaches that try to handle ambiguous adverbs in linguistic theory. The remainder of the paper describes an empirical study with a sentence-paraphraserating task and discusses the results of this experiment.

2 Psycholinguistic Studies on Ambiguity

In the last 40 years the focus of linguistically informed investigations of sentence comprehension was the processing of syntactic ambiguities. The question to be answered was whether non-syntactic information like semantic and pragmatic information guides the resolution of ambiguities. Interactive models like constraint-based accounts assume that all types of linguistic and non-linguistic information (e.g., plausibility, (situational) context, world knowledge) influence parsing. Modular models assume that the parser uses only syntactic information for structure building (see Pickering & van Gompel 2007 for an overview).

A similar split-up of approaches can be seen in research on lexical ambiguity. Most studies are interested in the role of context for ambiguity resolution (for an overview, see Simpson 1994). The question is to what extent higher level semantic representations (i.e., sentence or discourse semantics) constrain the interpretation of an ambiguous word. Two classes of models and empirical evidence for both of them exist: The modular approach assumes that both meanings of an ambiguous word (or the preferred meaning only) are activated independent of the context it appears in whereas the interactive approach allows access to only the contextual appropriate meaning.

Frazier & Rayner (1990), Klepousniotou (2002) and Pylkkänen, Llinas & Murphy (2006) point to a fact that has long been noted in linguistic theory: Lexical ambiguity is not a homogenous phenomenon, but is subdivided into two distinct types, namely homonymy and polysemy. For homonyms like bank, it is assumed that the two meanings which have no semantic relation to each other, at least synchronically, are stored with two separate lexical entries. For polysemous words like newspaper (physical object vs. institution vs. building etc.), the widespread assumption is that the different senses that are semantically related share the same lexical entry (see e.g., Bierwisch & Schreuder 1992). All three studies cited above found evidence for this assumption in terms of processing differences for homonyms in contrast to polysemes. With an eyetracking study, Frazier & Rayner (1990) found only reading time differences for sentences with homonyms (see examples in (2)). They interpret the results as evidence for an immediate semantic interpretation of homonyms. Participants chose the preferred reading (preferences were determined by an offline rating study) immediately, and had to reanalyze their interpretation when confronted with a continuation only compatible with the non-preferred reading as in example (2b). No such difference was found for polysemy as in the examples in (3). The authors assume that the full interpretation of polysemes is delayed until disambiguating information appears.

- The records were carefully guarded after they were scratched.

- The records were carefully guarded after the political takeover.

(3)

- The newspaper was destroyed, lying in the rain.

- The newspaper was destroyed, managing advertising so poorly.

But if disambiguating contextual information precedes the ambiguous word, both homonyms and polysemes show a preference for the preferred reading, even if contextual information biases the non-preferred reading. These data are evidence for the modular approach. Contextual information influences ambiguity processing, but cannot overwrite the preference for one of the two readings. I will come back to these data when I will formulate the hypotheses for the present study.

We saw that semantic context information can influence ambiguity resolution. It has also been shown that syntactic context influences the processing of noun-verb lexical ambiguities in English (e.g., She held the rose. vs. They all rose, see Tanenhaus, Leiman & Seidenberg 1979, among others). Another type of syntactic context information, namely the role of position information for the processing of ambiguous words, has not been investigated so far. In the following, I will focus on the role of position for ambiguous adverbials.

3 Position and Interpretation of Adverbials

It has long been noted that manner adverbs which typically describe some manner in which the situation referred to by the verb phrase is performed can occur in different positions and receive different readings dependent on their position.

This observation is illustrated in (4) (McConnell-Ginet 1982, but see also Austin 1961, Jackendoff 1972 for similar observations).

(4)

- Louisa departed rudely.

- Louisa rudely departed.

The adverb rudely in the sentence-final position as in (4a) receives a reading whereby Louisa departed in a rude manner, whereas the adverb in a higher position as in (4b) gets an interpretation whereby her act of departing was rude.

The examples in (5) show another type of interpretation variance dependent on position (see Ernst 2002).

(5)

- Alice has answered the questions cleverly.

- Alice cleverly has answered the questions.

According to Ernst (2002), (5a) represents the manner reading: Alice answered the questions in a clever manner (although it might have been stupid for her to answer at all). (5b) in contrast gets a subject-oriented interpretation in which Alice is clever for having answered the questions (although the content of each answer may be stupid).

Frey & Pittner (1998) point to another type of interpretation difference dependent on position. The German adverb langsam can either have the manner reading as illustrated in (6a). In the higher position in (6b), it receives an event-related interpretation.

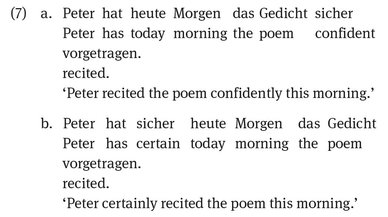

The German examples in (7) illustrate a similiar ambiguity. (7a) again represents the manner reading of the adverbial sicher (‘confident’) whereas the high position of the adverbial in (7b) goes along with a speaker-oriented interpretation (‘certainly’).

Note that, dependent on information-structural constraints like definiteness of the noun phrases and prosody, the low position in (6a) and (7a) is also compatible with the speaker-oriented interpretation which is also reflected in the frequency data below, but the experimental data will show that this reading is clearly dispreferred for the low position.

Two different accounts for these position-driven interpretation differences were proposed (see Rawlins 2008, for this categorization): The scope approach explains the interpretation difference in terms of differences in scope taking of the adverbial (e.g., Thomason & Stalnaker 1973). It is assumed that adverbs in a high position compose with something else than adverbs in a lower position. The lexical approach in contrast assumes that these adverbs have two different lexical entries, i.e. that they are homonyms. The two meanings are related to each other by a lexical rule (e.g., McConnell-Ginet 1982).

The aim of the present study is the attempt to differentiate between these two approaches empirically. First of all, the question is whether the position effect based on the intuitions of linguists can also be found in naïve speakers in a controlled experimental setting. To do so, the examples in (6), which are not discussed in the literature so far, were chosen.

On the basis of the two approaches together with the results from processing lexical ambiguities, the following predictions can be derived.

The scope approach predicts that the availability of the two readings depends upon the position of the adverbial: the manner reading should correlate with the low position, the speaker-oriented reading should correlate with the high position. It has been assumed that the base position of manner adverbs in German minimally c-commands the base position of the main predicate whereas the base position of speaker-oriented adverbials c-commands the base positions of all arguments and other adjuncts and the base position of the finite verb (see e.g. Frey 2003). With this approach, no preference for one of the two readings is predicted. First evidence for this assumption comes from a study on the processing of temporal adverbials (Stolterfoht 2012). In this study, I used sentences like the examples in (8)

(8) Der Tellerwäscher erzählt, dass …

(The dishwasher told that …)

(9)

- Preparing the tomato soup takes thirty minutes. process-related

- Preparing the tomato soup will start in thirty minutes. event-related.

Participants had to rate sentence paraphrase pairs (scale 5 (=‘highly acceptable’) – 1 (= not acceptable)): Sentences like (8a) and (8b) in combination with paraphrases like (9a) or (9b). The results revealed an interaction of adverb position and paraphrase. With a high adverb as in (8b), the event-related reading (9b) was rated higher than the process-related reading in (6a) (3.1 vs. 2.3). In contrast, with a low adverb the event-related reading was rated lower (2.4 vs. 3.3). No overall preference for one of the two readings was found (no significant main effect of paraphrase). These results show that the syntactic position of a temporal adverbial influences interpretation. The results can be explained within a scope approach that assumes one (underspecified) semantic representation for time-frame adverbials. The two interpretations arise from a difference in the syntax-semantics-mapping, i.e., the mapping from different modifier positions to different semantic domains. The early adverbial has scope over the event-external domain whereas the late adverbial composes with the process domain (e.g. Haider 2000, Ernst 2002, Rawlins 2008).

The lexicalist approach also predicts that the availability of the two readings depends upon the position of the adverbial. But on the basis of the data reported by Frazier & Rayner (1990), this approach, in contrast to the scope approach, predicts an overall preference for one of the two readings. One could ask whether ambiguous adverbs like sicher are homonyms or polysemes. According to McConnell-Ginet (1982), they are homonyms. But as contextual information in terms of syntactic position is available immediately, the prediction for both homonyms and polysemes would be the same. But what is the preferred reading for this kind of adverb? One well-known source of interpretation preferences is frequency. Therefore, I conducted a small-scale corpus search in the morphosyntactically annotated German corpus TIGER 1.0 consisting of 700,000 tokens (40,000 sentences) of German newspaper text (www.ims.stuttgart.de/projekte/TIGER). All occurrences of the ambiguous adverbs used in the study (sicher, bestimmt, ernsthaft) dependent on its assumed base position (high = preceding the subject; low = preceding the main predicate) were extracted. For the 56 occurrences of these adverbs, 31 had a speaker-oriented interpretation (17 in high position, 14 in low position) and 25 had a manner interpretation (all in low position). These results indicate a rather balanced occurrence of the two readings, with slightly more occurrences of the speaker-oriented interpretation, and therefore give us no reliable bias for a preference prediction.

From a diachronic perspective we can speculate that the manner reading from which the speaker-oriented meaning evolved over time is the preferred one (and this is what the data will show; but see the discussion below for another explanation of a manner preference in terms of focus structure).

To sum up, the main difference in the predictions derived from the two approaches is whether a preference for one of the two readings will be found or not.

4 The Experiment

With a questionnaire paraphrase rating study, I tested whether the two readings are psychologically real and whether they correlate with position. Furthermore, the data might also provide evidence for a possible overall preference for one of the two readings. An example of the experimental sentences is given in (10).

Target sentences

Adverb low

Peter hat heute Morgen das Gedicht sicher vorgetragen.

Peter has today morning the poem confident recited.

‘Peter recited the poem confidently this morning.’

Adverb high

Peter hat sicher heute Morgen das Gedicht vorgetragen.

Peter has certain today morning the poem recited.

‘Peter certainly recited the poem this morning.’

Paraphrases

manner

Souverän hat Peter heute Morgen das Gedicht vorgetragen.

Competent has Peter today morning the poem recited.

‘Competently, Peter has recited the poem this morning.’

Speaker-oriented

Zweifellos hat Peter heute Morgen das Gedicht vorgetragen.

Undoubtedly has Peter today morning the poem recited.

‘Undoubtedly, Peter has recited the poem this morning.’

The target sentences vary the position of the adverbial. The adverbial either appears between the finite verb and a temporal adverbial (high) or between the direct object and the participle (low). The paraphrases (manner vs. speaker-oriented) use partially synonymous adverbials to express the two readings of the ambiguous adverbials. To avoid position matching effects of target sentence and paraphrase, the adverbials in the paraphrases appear in the prefield (the position preceding the finite verb in German V2-clauses).

Predictions

- (i) If the two readings correlate with the position of the adverbial, an interaction of the two factors POSITION (high/low) and PARAPHRASE (manner/speaker-oriented) is expected. This result is predicted by the scope approach as well as by the lexicalist approach.

- (ii) If one of the two readings is preferred, a main effect of the factor PARAPHRASE is predicted (→ evidence for lexicalist approach). Diachronic evidence might predict a preference for the manner reading.

- (iii) If the two readings are equally available, no main effect of the factor PARAPHRASE (→ evidence for scope approach) is predicted.

4.1 Method

40 undergraduate students of the University of Tübingen were paid for their participation. All were native speakers of German.

Materials

Materials consisted of 24 experimental sentences and 62 filler sentences. Each experimental item was prepared in four versions which differed with respect to the position of the adverbial in the target sentence (high vs. low) and the following paraphrase (manner vs. speaker-oriented) (see examples in (10)). Three different ambiguous adverbials were used (sicher ‘certainly’/‘confident’, bestimmt ‘categorically’/‘decided’, ernsthaft ‘wholeheartedly’ /‘intensely’).

Design and procedure

Four presentation lists were constructed in which the 24 experimental items were randomly mixed with the 62 filler items. The four lists were counterbalanced across items and conditions: Each list included only one version of each experimental sentence-paraphrase pair. Half of the target sentences had a low adverbial, the other half had a high adverbial. Half of the paraphrase were manner, the other half were speaker-oriented. Thus, a 2 (high/low) by 2 (manner/speaker-oriented) -design was employed with both factors being manipulated within participants and within items.

Participants completed the questionnaire in the lab. They were told to read the two sentences (target sentences + paraphrase) carefully and to rate the adequacy of the second sentence as a paraphrase of the first one on a scale from 5 to 1. If the second sentence expresses exactly the same as the first sentence, then they should rate this sentence-paraphrase-pair ‘5’. If the second sentence is not a paraphrase of the first sentence, but expresses something else, they should rate this sentence-paraphrase-pair ‘1’. For graded judgments, they were told to use the values ‘4’, ‘3’ and ‘2’. Each experimental session lasted approximately 15 minutes.

Data Analysis

Participants’ ratings were analyzed with two separate ANOVAs, one with an error term that was based on participant variability (F1) and one with an error term that was based on item variability (F2). The independent variables were POSITION (high/low) and PARAPHRASE (manner/subject-oriented). The ANOVAs were 2 × 2 with repeated measurement on the two factors in both the participant- and the item-analysis.

The mean ratings are displayed in Table 1 and Figure 1.

Table 1: Mean ratings of sentence-paraphrase pairs

| Adverb Position | ||

|---|---|---|

| Paraphrase | early | late |

| manner | 3.07 | 4.07 |

| subject-oriented | 3.49 | 3.05 |

The analyses revealed significant main effects of POSITION (F1 (1,39) = 6.89, p1 ≤.01; F2 (1,23) = 30.55, p2 ≤.001) and PARAPHRASE (F1 (1,39) = 5.39, p1 ≤.05; F2 (1,23) = 15.74, p2 ≤.001), as well as a highly significant interaction of the two factors (F1 (1,39) = 20.84, p1 ≤.001; F2 (1,23) = 30.37, p2 ≤.001).

Figure 1: Mean ratings of sentence-paraphrase pairs

4.2 Discussion

The highly significant interaction of the two factors shows that the position of an ambiguous adverbial plays an important role for the interpretation of the sentence and can be found in naïve speakers in a controlled experimental setting: sentences with a high adverb got better ratings when paired with a subject-oriented paraphrase and sentences with a low adverb got better ratings when paired with a manner paraphrase. This result is predicted by both the scope approach as well as the lexicalist approach.

As predicted by the lexicalist approach, we found a main effect of the type of paraphrase, with an overall preference for the manner interpretation (3.56 vs. 3.28). This also fits well with the prediction derived from diachronic evidence. At first sight, this seems to be evidence for the lexicalist approach. But if we look at the full set of data, there is an additional main effect of adverb position, with higher overall ratings for the late adverb (3.57 vs. 3.27). This result was predicted by neither approach. The descriptive mean ratings given in Table 1 reveal that both main effects seem to be driven by the exceptional high ratings for the condition with a low adverb paired with a manner paraphrase. That means there is no overall preference for a manner reading. An explanation of this effect can be given in focus structural terms (thanks to Susanne Winkler for this suggestion). The low position with manner interpretation is also the accent position for the wide focus reading of the sentence (the data show that the subject-oriented reading is clearly dispreferred in this position).

Psycholinguistic evidence from auditory studies clearly indicates that perceivers’ attention is immediately directed to focused and accented material. Focusing by pitch accents leads to faster responses in phonological processing (Cutler & Fodor 1979), and, in addition, syntactic processing, e.g., syntactic ambiguity resolution, can be affected by focal pitch accents (Schafer, Carter, Clifton & Frazier 1996, Schafer, Carlson, Clifton & Frazier 2000, Carlson 2001, Carlson 2002).

There is also empirical evidence that phonological and prosodic representations are built up while reading a sentence. (see e.g., Rayner & Pollatsek 1989, Pollatsek, Rayner & Lee 2000) and that focusing in reading increases the salience of the focused constituent (Birch, Albrecht & Myers 2000) and leads to more careful encoding by the reader (Birch & Rayner 1997). Therefore, the manner reading is supported by two independent factors, syntactic position and pitch accent position. To find further evidence for this explanation, an auditory study with a manipulation of pitch accent position will be conducted. The prediction is an interaction of the factors accent and paraphrase.

To sum up, the present results cannot differentiate finally between the lexicalist and the scope approach. Nevertheless, two conclusions can be drawn from these data: Firstly, syntactic position guides the interpretation of a sentence. Readers use position information for the interpretation of ambiguous adverbials. Secondly, the comparison of ambiguous manner adverbs with temporal adverbials shows that with regard to syntactic position the class of adverbials is not a homogenous one. Further research will show how information structural factors like focus and prosody interact with the position and interpretation of adverbials.

References

Austin, John (1961) Philosophical papers. Oxford: OUP.

Axel-Tober, Katrin & Sam Featherston (2013) The expression of extrapropositional meaning: diachrony and synchrony. Project proposal C6. SFB 833 The construction of meaning – the dynamics and adaptivity of linguistic structures. University of Tübingen.

Bierwisch, Manfred & Robert Schreuder (1992) From concepts to lexical items. Cognition 42, 23–60.

Birch, Stacy, Jason Albrecht & Jerome Myers (2000) Syntactic focusing structures influence discourse processing. Discourse Processes 30.3, 285–304.

Birch, Stacy & Keith Rayner (1997) Linguistic focus affects eye movements during reading. Memory and Cognition 25.5, 653–660.

Carlson, Katy (2001) The effects of parallelism and prosody in the processing of gapping structures. Language and Speech 44.1, 1–26.

Carlson, Katy (2002) Parallelism and prosody in the processing of ellipsis sentences. New York, London: Routledge.

Cutler, Anne & Jerry Fodor (1979) Semantic focus and sentence comprehension. Cognition 7, 49–59.

Ernst, Thomas (2002) The syntax of adjuncts. Cambridge: CUP.

Frazier, Lyn, & Keith Rayner (1990) Taking on semantic commitments: Processing multiple mean ings vs. multiple senses. Journal of Memory and Language 29, 181–200.

Frey, Werner (2003) Syntactic conditions on adjunct classes. In: Ewald Lang, Claudia Maienborn & Catherine Fabricius-Hansen (eds.) Modifying Adjuncts (Interface Explorations 4). Berlin, New York: de Gruyter, 163–209.

Frey, Werner & Karin Pittner (1998) Zur Positionierung der Adjunkte im deutschen Mittelfeld. Linguistische Berichte 176, 489–534.

Haider, Hubert (2000) Adverb placement, convergence of structure and licensing. Theoretical Linguistics 26, 95–134.

Jackendoff, Ray (1972) Semantic interpretation in generative grammar. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Klepousniotou, Ekaterini (2002) The processing of lexical ambiguity: Homonymy and polysemy in the mental lexicon. Brain and Language 82, 205–223.

McConnell-Ginet, Sally (1982) Adverbs and logical form: A linguistically realistic theory. Language 58, 144–184.

Pickering, Martin J. & Roger P. G. Van Gompel (2007) Syntactic parsing. In: Matthew Traxler & Morton A. Gernsbacher (eds.) The Handbook of Psycholinguistics. San Diego: Elsevier, 455–503.

Pollatsek, Alexander, Keith Rayner & Hye-Won Lee. (2000) Phonological coding in word perception and reading. In: Allan Kennedy, Ralph Radac, Dieter Heller & Joél Pynte (eds.) Reading as a perceptual process: Oxford: Elsevier, 399–425.

Pylkkänen, Liina, Rodolfo Llinás & Gregory L. Murphy (2006) The Represenation of Polysemy: MEG evidence. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience 18.1, 1–13.

Rawlins, Kyle (2008) Unifying Illegally. In: Johannes Dölling, Tatjana Heyde-Zybatow & Martin Schäfer (eds.) Event Structures in Linguistic Form and Meaning. Berlin/New York: de Gruyter, 81–102.

Rayner, Keith & Alexander Pollatsek (1989) The Psychology of Reading. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice Hall.

Schafer, Amy, Juli Carter, Charles Clifton & Lyn Frazier (1996) Focus in relative clause construal. Language and Cognitive Processes 11.1/2, 135–163.

Schafer, Amy, Katy Carlson, Charles Clifton & Lyn Frazier (2000) Focus and the interpretation of pitch accents: disambiguating embedded questions. Language and Speech 43.1, 75–105.

Simpson, Greg B. (1994) Context and the processing of ambiguous words. In: Morton A. Gernsbacher (ed.) Handbook of Psycholinguistics. San Diego: Academic Press.

Stolterfoht, Britta (2012) Processing Temporality: Position Determines Interpretation. Poster presented at the 25th Annual CUNY Conference on Human Sentence Processing. New York City, NY, March 2012.

Tanenhaus, Michael K., James M. Leiman & Mark S. Seidenberg (1979) Evidence for multiple stages in the processing of ambiguous words in syntactic contexts. Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior 18, 427–441.

Thomason, Richmond & Robert Stalnaker (1973) A semantic theory of adverbs. Linguistic Inquiry 4, 195–220.

Traugott, Elisabeth C. (1982) From propositional to textual and expressive meanings; Some semantic-pragmatic aspects of grammaticalization. In: Winfried P. Lehmann & Yakov Malkiel (eds.) Perspectives on Historical Linguistics. Amsterdam: Benjamins.