The Influence of Prosody on Children’s Processing of Ambiguous Sentences

Abstract: Studies in adults have shown that syntactic ambiguity can be effectively resolved with the help of prosodic cues, studies in children have found little or no effect of prosody on ambiguity resolution. In view of this discrepancy, a picture selection task was designed in order to investigate whether children can resolve syntactic ambiguities with the help of strong prosodic boundary cues.

This paper argues that children are capable of prosodic disambiguation using the same processing mechanisms as adults. The results clearly support this hypothesis and refute claims that children are unable to resolve syntactic ambiguities with the help of prosody. The results can also make a tentative statement about the point at which prosody is integrated in processing.

1 Introduction

This paper investigates the role of prosody in children’s processing of globally ambiguous sentences such as (1).

The ambiguity used in this study is a structural ambiguity which only arises in the oral realization of the test sentences and can be intonationally disambiguated. Depending on the location and length of the prosodic boundary, the sentence can be parsed either as one clause where the verb draw is transitive (2a) or as two intransitive sentences (2b).

(2)

- Mary draws the boy’s hammer.

- Mary draws. The boys hammer.

Structurally, the ambiguity in sentence (1) can be compared to early / late closure ambiguities such as (3).

(3)

- When Roger leaves the house is dark.

- When Roger leaves the house it’s dark. (Kjelgaard & Speer 1999, 156)

In both cases, the syntactic structure can be mapped directly onto the prosodic structure. That is, the distribution of intonational phrases (IPhs) corresponds with distribution of clause boundaries.

(4)

- (Mary draws the boy’s hammer)IPh

- (Mary draws)IPh (The boys hammer)IPh

(5)

- (When Roger leaves)IPh the house is dark.

- (When Roger leaves the house)IPh it’s dark. (Kjelgaard & Speer 1999, 156)

For adults, experiments on early / late closure ambiguities (Kjelgaard & Speer 1999, Schafer et al. 2000, Speer et al. 1996) showed that the existence of a prosodic boundary can facilitate comprehension and that prosodic disambiguation is easier when prosodic structure coincides with syntactic structure (Anderson & Carlson 2010). Price et al. (1991) stipulated that listeners associate relatively larger prosodic breaks with syntactic breaks and that syntactic boundaries of clauses that contain complete sentences nearly always coincide with major prosodic breaks (see also Wagner & Watson 2010).

Whereas comprehension of early / late closure ambiguities is facilitated by prosody, adults have problems resolving syntactic ambiguities when a prosodic boundary does not coincide with a major syntactic unit. In DP / clause ambiguities such as (6) IPh boundaries and syntactic clause boundaries do not necessarily match. Anderson & Carlson (2010) were able to show that speakers tend not to place an IPh boundary after the main verb.

(6)

The jury believed [the defendant had committed the crime]. (qtd. in Anderson & Carlson 2010, 473)

They argued that speakers’ mapping from syntax to prosody did not give them any incentive to insert a prosodic boundary after believed as the main clause and the verb phrase are equally incomplete at this point (c.f. Cooper & Paccia-Cooper 1980). The fact that speakers have many prosodic options for sentences like (6) makes prosodic boundary cues less helpful and prosodic disambiguation for the listener more difficult.

The studies presented so far, could lead to the assumption that a prosodic effect is only noticeable when prosodic and syntactic clause boundaries coincide. However, studies on the attachment of Prepositional Phrases (PP) suggest otherwise. PP attachment ambiguities like the one presented in (7) were reliably disambiguated with the help of prosodic boundary cues in several experiments (Schafer 1997, Pynte & Prieur 1996).

(7) Paula phoned her friend in Alabama. (qtd. in Schafer 1997, 52)

In (7), The PP in Alabama can either be attached to the NP friend or to the VP phoned.

According to Schafer (1997), those kind of attachment ambiguities show that prosodic boundaries play a central role in providing information about how the linguistic signal is structured and are not just additional evidence for the existence of clause boundaries. She suggests that there is a phonological module to the processing system which builds up a prosodic representation of the incoming material. The prosodic representation is then made available to the higher processing modules. Thus, the input into the syntactic module does not only consist of a string of words but is already pre-shaped by the phonological component. Those prosodically-defined domains then determine the salience of potential attachment sites. Thus, syntactic attachment effects are not only caused by “the particular syntactic content of the material in a phonological phrase” (e.g. minimal attachment and late closure) but also by the “overall pattern of phonological phrasing for the utterance” (Schafer 1997, 43). Out of these assumptions Schafer developed the prosodic visibility hypothesis:

(8) Prosodic Visibility Hypothesis:

The phonological phrasing of an utterance determines the visibility of syntactic nodes.

Nodes within the phonological phrase currently being processed are more visible than nodes outside of that phonological phrase; visibility is gradient across multiple phonological phrases.

In first analysis and reanalysis, attachment to a node with high visibility is less costly in terms of processing/attentional resources than attachment to a node with low visibility. (Schafer 1997, 42)

Schafer’s theory therefore complements Frazier’s garden path model (1978). In Frazier’s modular account the processor initially pays attention to syntactic information only and there is no interchange between the different modules of language processing. However, although initial processing is modular, subsequent processing does not have to be modular. According to Schafer, the syntactic module has already been modified by the phonological component. Contrary to this view, there are other modular accounts of parsing which claim that prosody only contributes to the reanalysis of a syntactically analyzed sentence. Pynte & Prieur (1996) argue along those lines.

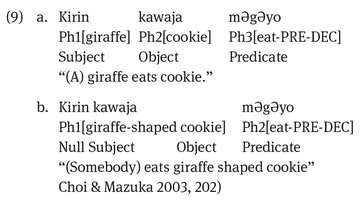

Most studies on children’s use of prosody employ globally ambiguous sentences and feature some kind of picture selection task. With regard to what we know about adults’ use of prosody in PP attachment ambiguities, we would expect to see that children’s actions are also affected by prosody. However, until recently, it seemed that prosody had little or no effect on children’s interpretation of those sentences (Choi & Mazuka 2003, Snedeker & Trueswell 2001, Vogel & Raimy 2002). Choi & Mazuka (2003), for example, argued that 5-to 6-year-old children were not able to use prosodic information to resolve structural ambiguities. They tested both Korean adults and children using sentences such as (9).

A phrasal boundary between kirin and kawaja indicates that kirin functions as the subject of the sentence. No boundary between kirin and kawaja groups the words together so that they form the object of the sentence.

In the experiment, the participants listened to the ambiguous sentence and then had to choose between two pictures depicting the two possible interpretations, i.e. a giraffe eating a cookie and someone eating a giraffe-shaped cookie. Whereas adults were able to disambiguate the syntactic ambiguity with the help of prosody, children were not. Choi & Mazuka concluded that children failed to use prosody in order to resolve syntactic ambiguities. This result is surprising and contradicts the predictions made by Schafer’s prosodic visibility hypothesis. However, it seems possible that children’s insensitivity could stem from their problem with interpreting pro (Isobe 2007). In order to help children overcome their difficulties with the null-subject, Isobe (2007) provided additional context information. His experiment showed that children were able to use prosody for structural disambiguation once contextual information was provided.

In 2008, Snedeker & Yuan used eye-tracking as a more sensitive measure for the influence of prosody on children’s processing of PP attachment ambiguities such as (10).

- (You can feel the frog)IPh with the feather.

- (You can feel)IPh the frog with the feather. (Snedeker & Yuan 2008, 574)

The results for the first part of the experiment showed that prosody had a moderate but reliable effect on interpretation. The children performed instrument actions more often when instrument prosody was used. The proportion of instrument reactions decreased when modifier prosody was used.

The results are in accordance with Schafer’s prosodic visibility hypothesis. In sentence (10a), no processing difficulty occurs because there is already a structural bias for VP attachment, which is then confirmed by the output of the prosodic module. In sentence (10b) the syntactic bias can be overcome by the fact that the VP is less visible. As attachment to a node with low visibility is more costly than attachment to a node with high visibility, a modifier interpretation is more readily available.

2 Predictions

The experiment discussed in this paper uses globally ambiguous sentences like (1) to examine the effects of prosody on syntactic processing of children. The experimental material differs from previous material as it combines a global ambiguity with a structure where prosodic and syntactic boundaries coincide. This kind of structure is normally found in temporarily ambiguous early / late closure ambiguities which showed very stable results for adults. We expect that the strong prosodic boundary cues should make methods like eye-tracking unnecessary. Our material enables the experimental set-up to be more playful and less stressful for the children.

We agree with Schafer (1997) and hold the view that for both adults and children prosodic structure informs syntactic parsing decisions. This leads to our hypothesis that processing difficulties associated with the less favoured syntactic analysis should disappear when sentences are spoken with felicitous prosody.

For our material we assume a natural bias towards the one sentence interpretation (Mary draws the boy’s hammer). Our claim is justified both by Frazier’s late closure theory as well as by Hoeks’ et al. thoughts on topic structure.

Studies have repeatedly found a processing advantage for late closure sentences (Frazier & Rayner 1982, Kjelgaard & Speer 1999). For Frazier (1987) and others, this preference is due to structural simplicity. Frazier’s garden path model predicts that initial parsing is directed by two fundamental principles: minimal attachment and late closure. Minimal attachment stipulates that an ambiguous phrase is attached to the proceeding tree structure using the fewest number of nodes (Frazier 1987, 562). The principle of late closure predicts that attachment to preceding items is favored over attachment to subsequent items, provided that two equally minimal attachments exist (Frazier 1987, 567). According to late closure, a phonological string like ðə bɔjz drʌm should preferably be attached to the preceding string and interpretation (11a) should therefore be favored over interpretation (11b).

- Mandy plays the boy’s drum.

- Mandy plays. The boys drum.

However, it is not only syntactic simplicity which promotes a one sentence interpretation. With respect to gapping structures, Hoeks et al. (2006) explained the preference of nongapping sentences with the principle of minimal topic structure. This stipulates that readers, and listeners alike, prefer to have only one topic in any given utterance. They concluded that gapping structures were more difficult to process because of their complex topic structure and not because of their syntactic complexity. Their approach is not only useful for sentence coordinations but can be transferred to the interpretation of two independent clauses. Since interpretation (11a) is about a single topic (i.e. Mandy), it should be preferred over sentence (11b) which is about two topics (i.e. Mandy, the boys).

The purpose of the following experiment is to establish whether children can overcome this preference with the help of prosodic cues. As suggested by Schafer’s prosodic visibility hypothesis, prosody should structure the language input and therefore make the two sentence interpretation more readily available when an agreeing prosody is used. Since the VP in sentence (11b) is prosodically less visible (due to the pause) when reaching the boys, attachment of the DP to the preceding item should be prohibited and the start of a new sentence with a new topic should be facilitated.

3 Method

3.1 Participants

22 children aged 6 participated in the study. The children were pupils at Rathmichael Elementary School in Shankill, Ireland. All the children that began the experiment completed it and were included in the analysis. Each child listened to eight test items recorded in both one-sentence prosody and two-sentence prosody.

The experimental set-up also included four unambiguous fillers such as (12) and (13).

(12) Kate plays the boy’s guitar.

(13) Molly drinks. The boys eat.

3.2 Stimuli

This paper will use the prosodic hierarchy first described by Pierrehumbert and colleagues (Pierrehumbert 1980, Beckman & Pierrehumbert 1986, Pierrehumbert & Hirschberg 1990, Beckman 1996) and follow the conventions of the English ToBI annotation system (cf. Beckman & Ayers 1997). According to this system, each utterance is built up of Intonational Phrases (IPh) which consist of at least one Phonological Phrase (PPh). Intonational Phrases end with either a high (H%) or a low boundary tone (L%), Phonological Phrases end with either a high phrase accent (H-) or a low phrase accent (L-). The end of an Intonational Phrase is therefore marked by the combination of the PPh-final phrase accent and the IPh-final boundary tone. Our analysis also includes break indices which range from 1 (break between two words) to 4 (break between two intonational phrases).

Although the ambiguity used in this study is a structural ambiguity, we will refer to it as IPh-ambiguity since the listener has to locate the IPh boundary in order to understand the intended meaning. For sentence (2a) the only IPh boundary with low phrase accent (L-) and low boundary tone (L%) occurs after hammer. Within the sentence there are only minor breaks (level 1) separating each word (cf. figure 1).92

Figure 1: Pitch Extraction Contour of Example (2a).

Figure 2: Pitch Extraction Contour of Example (2b).

Contrary to (2a), (2b) has two IPh boundaries (cf. figure 2). The first one occurring after draws, including a high phrase accent (H-) and a high boundary tone (H%) as well as a level 4 break. The second IPh boundary occurs after hammer and has the same features as the one in (2a). Thus, whereas sentence (2a) has only one sentence final IPh boundary, sentence (2b) has two IPh boundaries, corresponding with the two syntactic clause boundaries. The prosodic cues should therefore be fairly strong.

The sentences were spoken by a female speaker of general American English and recorded as 16-bit digital sound files which were sampled at 22.1 kHz. Phonetic indicators of the prosodic boundary included: i. lengthening of the clausefinal syllable; ii. a clause-following silence; iii. a pitch discontinuity between the end of the first clause and the beginning of the second clause. Table 1 gives an overview of these three factors in the relevant ambiguous sentences.

Table 1: Characterization of the Test Items

The children heard both versions of the sentence. As figure 3 illustrates, the set of pictures which accompanied the critical sentences always contained: i. a picture corresponding to the one-IPh interpretation (for figure 3: the girl painting the hammer); ii. a picture depicting the two-IPh interpretation (for figure 3: the girl painting and the boys hammering); iii. a distractor picture depicting a different scene (for figure 3: the girl playing the violine).

Figure 3: Set of Pictures for the Picture Selection Task

3.3 Procedure

The children were tested in two groups of eleven in their familiar classroom in school. During the experiment, they sat on their own to prevent them from copying each other. They were told that the experimenter was from Germany and was staying in Ireland to learn English. They were then asked if they could help the experimenter with some difficult English sentences. In order to make it a bit more fun, the experimenter had designed a listening game.

At the beginning of each trial, the children were asked to pick up an envelope which was placed on a chair. They were instructed to open the envelope and take out the three pictures. When they were ready, the experimenter played a pre-recorded sound file from a computer connected to external speakers. Each sentence was repeated once. The children got the instruction to put the picture which was described back into the envelope and then to put the envelope underneath the chair. After they had finished the task, they were asked to get the next envelope from the chair. Both the experimenter as well as a class teacher were present and encouraged the children to listen closely. The children internalized the procedure very quickly and stayed focused throughout the experiment.

4 Results

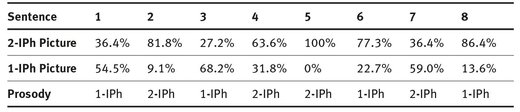

Sentence one to five showed a correlation between prosody and interpretation. However, in sentence six to eight the participants appeared to have acted against the interpretation favored by prosody (cf. table 2).

Table 2: Results

The highest correct response rate for one-IPh prosody received sentence three (Mandy plays the boy’s drum) with 68.2% of all children choosing the corresponding picture (cf. table 2). For two-IPh prosody, sentence five received the highest correct response rate with 100%. The next highest rating for two-IPh prosody was still higher than the highest rating for one-IPh prosody. Sentence two (Diana drinks. The boys drink) received 81.1% correct responses. Furthermore, when comparing the total of one-IPh responses with the total of two-IPh responses, it can be seen that the rate of two-IPh responses was higher than the rate of one-IPh responses (cf. figure 4).

5 Discussion

The main goal of the experiment was to find an answer to the following questions: Firstly, can children’s syntactic bias be overridden by prosodic cues? Secondly, if so, at what point does prosody come into play?

Children’s interpretation for sentence one to five shows that prosody plays a crucial role in sentence processing. If anything, children are more sensitive towards prosodic cues than adults. Not only was the interpretation supported by prosody the preferred one in each sentence, prosody could even override the initial one-IPh bias when two-IPh prosody was used. The fact that the total rate of correct responses was higher for two-IPh prosody than for one-IPh prosody would suggest that children are even more reliant on prosodic structuring than adults.

The results are in correspondence with Schafer’s visibility hypothesis and lead to the conclusion that prosody can structure syntactic input in both adults and children. This explains why the children chose the structurally more complex interpretation when favored by prosodic structuring. In item (2), (4) and (5) the initially favored VP-attachment was prohibited due to the low visibility after the prosodic break.

Studies on adult sentence parsing found that processing was hugely facilitated by prosody. This is especially true for early versus late closure ambiguities. Due to the similarities between early versus late closure ambiguities used for adults and the ambiguity used in this study, it is not far-fetched to conclude that very young children as well as adults are sensitive to prosodic cues and that children use them in an adult-like fashion when processing sentences.

This study also suggests that children are not only able to use prosodic cues, but that they do so at first hearing and not at the point of reanalysis. We can therefore provide evidence for a processing system which is not strictly modular. As the sentences are globally ambiguous, both interpretations can be considered as valid. If children’s initial parsing decision was based on syntax only, there would be no need to revise this decision. A one-IPh preference would be expected.

However, even though there is a strong correlation between prosody and interpretation in sentence one to five, in sentence six to eight, prosody and final interpretation do not correlate. Nevertheless, the results do not necessarily have to reflect children’s inability to use prosodic cues but are probably due to the experimental set-up. When analyzing the experiment it became clear that there was a priming effect for the last three test items which was caused by the unambiguous fillers as well as by preceding test items. Even though this study can make tentative suggestions concerning the role of prosody in child processing, several alteration of the experimental set-up are necessary.

The priming effect in the last three test items shows that children are very sensitive towards parallelism and repetition. The internal and external parallelism in sentence (6) (Diana drinks the boy’s drink) even biased the children towards the 2-IPh interpretation which was both structurally and prosodically disfavoured. In order to get results that are more reliable, these factors need to be controlled to prevent priming. It would be interesting to see whether a higher variety in both test items and fillers might lead to clearer results for the sentences in the second part of the experiment.

Additional areas for further research include the relation between prosody and working memory and the comparison between children and adults. There is clear evidence that memory capacity has a great influence on language processing. It would be interesting to investigate whether a relatively lower working memory leads to a higher prosodic sensitivity as it is implied by Schafer’s hypothesis.

Although the ambiguity used in this study has not been investigated with adults before, earlier experiments suggest that adults should be able to integrate the prosodic cues and solve the ambiguity with the help of prosody. A comparative experiment could provide additional evidence that there are no qualitative differences between the processing mechanisms of adults and children.

References

Anderson, Catherine & Katy Carlson (2010) Syntactic Structure Guides Prosody in Temporarily Ambiguous Sentences. Language and Speech 53, 472–493.

Beckman, Mary E. (1996) The Parsing of Prosody. Language and Cognitive Processes 11, 17–67.

Beckman, Mary E. & Gayle M. Ayers (1997) Guidelines for ToBI Labelling, Version 3.0. Ohio State University.

Beckman, Mary E. & Janet B. Pierrehumbert (1986) Intonational structure in Japanese and English. Phonology Yearbook 3, 255–309.

Choi, Youngon & Reiko Mazuka (2003) Young Children’s Use of Prosody in Sentence Parsing. Journal of Psycholinguistic Research 32, 197–217.

Cooper, William E. & Jeanne Paccia-Cooper (1980) Syntax and Speech, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Frazier, Lyn (1978) On Comprehending Sentences: Syntactic Parsing Strategies. Ph.D. Diss., University of Connecticut.

Frazier, Lyn (1987) Sentence Processing: A Tutorial Review. In: Max Coltheart (ed.) Attention and Performance XII. The Psychology of Reading. Hillsdale, N.Y.: Erlbaum, 559–586.

Frazier, Lyn & Keith Rayner (1982) Making and Correcting Errors During Sentence Comprehension: Eye Movements in the Analysis of Structurally Ambiguous Sentences. Cognitive Psychology 14, 178–210.

Hoeks, John C. K., Petra Hendriks & Wietske Vonk (2006) Processing the NP-versus S-Coordination Ambiguity: Thematic Information does not Completely Eliminate Processing Difficulty. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology 59(9), 1581–1599.

Isobe, Miwa (2007) The Acquisition of Nominal Compounding in Japanese: A Parametric Approach. In: Alyona Belicova, Luisa Meroni & Mari Umeda (eds.) Proceedings of the 2nd Conference of Generative Approaches to Language Acquisition North America. Somerville, MA: Cascadilla Proceedings Project, 171–179.

Kjelgaard, Margaret M. & Shari Speer (1999) Prosodic Facilitaion and Interference in the Resolution of Temporary Syntactic Closure Ambiguity. Journal of Memory and Language 40, 153–194.

Pierrehumbert, Janet B. (1980) The Phonology and Phonetics of English Intonation. Ph.D. Diss., MIT.

Pierrehumbert, Janet B. & Julia Hirschberg (1990) The Meaning of Intonational Contours in the Interpretation of Discourse. In: Philip R. Cohen, Jerry Morgan & Martha E. Pollack (eds.) Intentions in Communication. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 271–311.

Price, Patti, Mari Ostendorf, Stefanie Shattuck-Hufnagel & Cynthia Fong (1991) The Use of Prosody in Syntactic Disambiguation. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 90, 2956–2970.

Pynte, Joel & Bénédicte Prieur (1996) Prosodic Breaks and Attachment Decisions in Sentence Parsing. Language and Cognitive Processes 11, 165–192.

Schafer, Amy J. (1997) Prosodic Parsing: The Role of Prosody in Sentence Comprehension. Ph.D. Diss., University of Massachusetts.

Schafer, Amy J., Shari R. Speer, Paul Warren & S. David White (2000) Intonational Disambiguation in Sentence Production and Comprehension. Journal of Psycholinguistic Research 29,169–182.

Snedeker, Jesse & Sylvia Yuan (2008) Effects of Prosodic and Lexical Constraints on Parsing in Young Children (and Adults). Journal of Memory and Language 58, 574–608.

Snedeker, Jesse & John Trueswell (2001) Unheeded Cues: Prosody and Syntactic Ambiguity in Mother-Child Communication, Paper presented at the 26th Boston University Conference on Language Development. (non vidi).

Speer, Shari, Margaret M. Kjelgaard & Kathryn M. Dobroth (1996) The Influence of Prosodic Structure on the Resolution of Temporary Syntactic Closure Ambiguities. Journal of Psycholinguistic Research, 25, 247–268.

Vogel, Irene & Eric Raimy (2002) The Acquisition of Compound vs. Phrasal Stress: The Role of Prosodic Constituents. Journal of Child Language 29, 225–250.

Wagner, Michael & Duane G. Watson (2010) Experimental and theoretical advances in prosody: A review. Language and Cognitive Processes 25, 905–945.