CHAPTER 7

People

A BUSINESS ORGANIZATION is like the human body The human body. contains autonomic nerves that work without regard to human wishes and motor nerves that react to human command to control muscles.

At Toyota, we began to think about how to install an autonomic nervous system in our own rapidly growing business organization. In our production plan, an autonomic nerve means making judgments autonomously at the lowest possible level; for example, when to stop production, what sequence to follow in making parts, or when overtime is necessary to produce the required amount.

People are fundamental to lean. It is through people that the lean system learns and improves. To fully utilize the skills and ability of the people in the system, the jobs have to be designed to allow them to think and to share their learning with others. While highly skilled and motivated workers are needed, individual craft production is actively discouraged. Rather lean seeks to scientifically understand the craft, so that the craft can become standard.

When he took over Toyota’s machine shop in 1946, Ohno stated that:

The first thing that I did was standardization of jobs. … we first made manuals of standard operation procedures and posted them above the work stations so that supervisors could see if the workers were following the standard operations at a glance. Also, I told the shop floor people to revise the standard operating procedures continuously saying, “You are stealing money from the company if you do not change the standard for a month.” (Fujimoto 1999, p. 64 from Stalk, Stephenson and King 1996)

There are three points in the previous quote. One is that improvement was made by standardizing jobs at every position in the shop. The second is that the standards were visually posted so that they could be easily reviewed by everybody in the company and enforced, if necessary. Finally, that the standards were not set in stone. Instead, the standards became the baseline for improvement, and that improvement was expected.

Toyota did adopt the Taylor’s approach to standardization. Every operation was done using the single best way of performing the operation. But, Toyota did not adopt the Taylor approach of freezing the standard. Toyota did not freeze standard operations, which in other companies created a vertical division between the workers and the engineers and managers. Toyota insisted on continuous improvement in the standards and that this continuous improvement in the standards was to be accomplished by those performing the work—that is, the people.

It is possible for organizations to improve by integrating new technology into their systems. The technology will provide new ways of doing the work. But, people are still there. As Shingo pointed out:

No matter what the level of automation, people will always be an essential and vital part of production. (Shingo 1989, p. 60)

Action is taken by people. People make the decisions to respond to change. People solve the problems. People create the innovations. People affect each of the basics that we have discussed up to this point in the book.

It is people who identify the customer needs and translate these needs into products and services.

It is people who design the process flow and who perform the operations in the process to provide the products and services.

People influence all three variables in Little’s Law: inventory, lead time, and throughput rate. People provide the service and help determine the average time at which work is processed. As people improve the process and reduce the time to perform process activities, the improvement can be tracked using Little’s Law (I = R × T ).

As discussed earlier, increased variance increases the buffer requirements and reduces responsiveness to the customer and to changes in the market. It is the people in the organization who can help eliminate variance in processes or, unintentionally, increase variance in the processes.

Buffers protect the system throughput from variance in the system. However, people have to manage the buffers to provide the appropriate protection. It is people who are closest to the day-to-day work who can fine tune the buffer management plan to improve system performance.

Organizational Learning and People

Organizations only learn if the people in them learn. If an individual in an organization learns how to perform a task better, it is possible for the organization to learn by having others adopt the new improved standard.

Organizational learning requires individuals to learn and to encode their learning into the systems, subsystems, policies, and procedures of a company. If they can encode their learning into these systems and subsystems, then the company as a whole will respond differently to future events than it did to past events.

In terms of organizational learning, the use of standards for all tasks transforms tacit knowledge into explicit knowledge, which becomes the performance baseline. Improvement that is then immediately translated into new standard operating procedures, which creates a new performance baseline for workers’ performance.

Lean Work Design and People

Lean work design is concerned with organizing the flow of work so that the efforts of people are most effectively coordinated and directed to satisfy the customer more completely. The work design of the system is often performed in a hierarchical manner and involves all the levels of management at various points in the work design. The middle managers operationalize the goals of upper management through their design or redesign of the work.

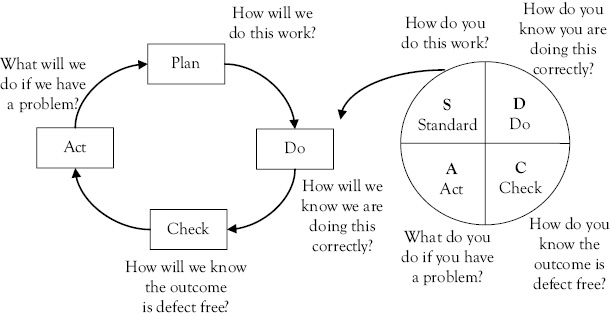

The ongoing cycle of using standard operating methods for every job while continuously improving the job is often illustrated using the Plan-Do-Check-Act (PDCA) cycle as depicted in Figure 7.1. This PDCA cycle is an implementation of the scientific method. The “Plan” step is what we intend to do and how we intend to do it. In the PDCA cycle, the “Do” step should be done according to a standard, which is the “S” step in the small Standard-Do-Check-Act (SDCA) cycle that is next to the Do step of the SDCA cycle. The SDCA cycle is what the company is doing when it produces to standard. In the SDCA cycle the company has a Standard which is used in the Do step. The Do step is where the work is done. In the Check step, the employee checks whether the standard was actually effective during the Do step. If the Check step confirmed the standard was good, then the Act step is to continue with the Standard. If the standard was not found to be effective then the Act step is to change the standard.

Managers can drive the implementation and maintenance of a lean work design by continuously engaging their employees in answering four basic questions (from Spear and Bowen 1999).

How do you do this work?

How do you know you are doing this correctly?

How do you know this outcome is defect free?

What do you do if you have a problem?

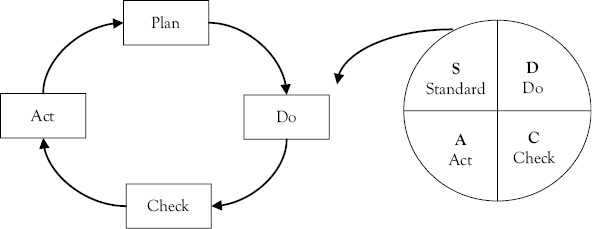

Managers can drive the PDCA cycle by repeatedly asking these questions and listening to the answers. This is illustrated in Figure 7.2. The first time the questions are asked is focused on SDCA. Are the employees using the standard procedures? The next set of questions is PDCA, in that they are focused on having the employees improve the process. The manager is ensuring that there is a channel of communication that incorporates each employee into the work design process. So, those who are essential to the delivery of the work are involved in the design of the work. For example, the answer to the question of “How do you do this work?” should not only inform the manager about the actual process used to perform a task, but also whether there is a standard process that is consciously followed. If there is no standard process, then the first improvement is to develop and implement a standard. In addition, if there is no standard, then the standard creation is involving the employee at the lowest level in the creation of the standard.

Figure 7.1 Standard operations and continuous improvements of standards: PDCA and SDCA cycles

Figure 7.2 Driving PDCA with questions

By asking these questions, the manager builds the confidence of the employees and ensures that the lowest level of the firm that is involved in the decision is competent to make the decision. This is a very basic, but important change from Fordism and Taylorism, which rely primarily on the knowledge of the managers and engineers to make day-to-day decisions as well as decisions about process improvements. However, while lean gives decision-making power to the line worker, lean does not make the role of the manager less important, rather it changes the role of the manager and makes the manager’s role even more challenging in the organization.

… standard work procedures, corresponding to each player’s ability, must be adhered to at all times. When abnormalities arise— that is, when a player’s ability cannot be brought out—special instruction must be given to bring the player back to normal. This is an important duty of the coach. (Ohno 1988, p. 8)

Ohno explains the role of standardization in creating a highly coordinated team of employees by viewing the plant as a baseball team. In this analogy the managers and supervisors are the team manager and the coaches and the line workers are the players on the field. The players have practiced working together and have become a team. They have mastered the plays, which they have to perform during a game and they have learned to respond to any situation with coordinated action. To achieve this coordinated team play, they developed and used standard work procedures. These procedures (i.e., plays) are adapted to correspond to each player’s ability.

Just as in a baseball team, the production team also must have the same goals (i.e., the goals must be aligned) for the team to be successful. So the first role of the manager is to ensure that everyone knows the goals, and what they must do to achieve the goals.

The baseball team manager keeps the entire team focused on responding to the changing situations from game to game and during a particular game. The players do the work (i.e., fielding and hitting), but the manager is evaluating their strengths and weaknesses. In a company, the manager keeps the team focused on meeting the needs of the customers. It is essential for a lean work design to be effective that everyone within the company sees it as their responsibility to meet the customers’ needs. This includes upper management and middle management, as well as the front-line employees. At each level, the people in the company have to answer the question of “How does the work that they are doing addresses the customers’ needs?” For everyone to answer this question, the customers’ needs have to be clearly communicated to everyone.

Lean Work Design and Employee Empowerment

Managing people within a lean work design requires the manager to understand the level of involvement and empowerment needed from the employees at each level. Empowerment means “to invest with power or official authority” (American Heritage 2007, p. 451). Empowerment changes the role of everybody in the company compared to classical mass production, because empowerment means that everyone is expected to ensure that their work meets the customer needs. This means that everyone is responsible for improving their work processes. Employees cannot wait for someone at a higher level in the hierarchy to suggest improvements. This does not mean that there are no roles, and that employees are not constrained by their roles. Everybody in the organization has to understand their role and have the skills necessary to competently perform their assigned roles. Therefore, empowerment requires training on how to perform on the team.

Example: Crew resource management is an example of employee empowerment. Airlines provide training to their cockpit crews to ensure they have the interpersonal skills to communicate effectively as a member of the flight deck crew. The crew resource management training was instituted after an air crash where a crew member tried to indirectly give the captain critical information and tried to indirectly inform the captain that the plane was about to crash. However, before the captain understood the problem the plane crashed. The crew resource management training consists in teaching the crew member how to: (1) get the attention of the captain; (2) state their concern in clear, direct language; (3) state the problem; (4) state a possible solution; (5) attempt to obtain agreement. This crew resource management training has since been adapted for use in maintenance crews, firefighting crews and so on.

In the lean system, the worker is responsible for identifying when the system is not performing within specifications and to stop it. Once stopped, the workers can call for assistance or repair the system themselves.

The empowerment phase is often marked by initiation of training and promotion unequivocally intended to reach everyone in the company. The training needs to cover what can be done and what must be done in terms of both technical skills and people issues. (Shiba and Walden 2001, p. 456)

It is important to recognize that empowerment requires training, because part of empowerment is the capability to perform competently. Methods must be provided to employees that allow them to make decisions for process improvements in a coordinated manner. This is often done through the use of quality improvement teams. A worker can be a member of a team that is addressing an on-going problem in order to develop a solution by eliminating the root cause of the problem. The team will have standard procedures for its problem identification and solution and the creation of new work standards.

Worker empowerment and the use of workers for continuous improvement does not mean that the manager or supervisor is not required. Just as the coach of a baseball team is constantly watching to find ways to improve, the manager and the supervisor must also constantly observe to find ways to improve the performance of the systems they manage.

Empowerment makes everyone responsible for learning and sharing what they have learned. As the workers and managers learn, the company learns. The learning is captured by the company in its routines or standard operating procedures. All people have knowledge about how to perform their job. Often, this knowledge is not explicit knowledge that can be transferred easily for example, by writing it down. The knowledge that we have about how to perform our task is often tacit knowledge, which is difficult to share. Tacit knowledge in the form of “know-how” and “practical knowledge” is closely associated with production tasks and its transfer can be complex (Grant 1996).

Example: A recipe in a cookbook is explicit knowledge. The list of ingredients and the set of steps in combining the ingredients is easily transferable from one person to another. However, as we all know from our own experience, a “great” meal requires more than just a recipe. A great cook can transform a so-so recipe into a great meal. This tacit knowledge of the cook is difficult to transfer, since a cook may not know how to explain his or her “magic touch”. Often, the master chef can guide the novices to provide the little touches and adjustments that make their own efforts superior. By working together, the master chef is able to transfer this tacit knowledge about cooking.

By establishing standard operating procedures and insisting that they be rigorously adhered to, lean operations seek to convert the tacit work knowledge into explicit work knowledge. Standards can be enforced in part by writing them down, but also some of it may be shared by one worker demonstrating to another how to do a job or task. By requiring constant improvement in the standard operating procedures, lean pushes those workers who are actually doing the tasks to seek improvements in their task performance. As they revise the standard operating procedures, they are sharing the improvements they found with others.

Customers want changes that improve the services or products they receive. So, the requirements of each job or task will also change. For a company to change in order to better respond to its customers, it must change its systems, subsystems, policies, and procedures. To do that, the people involved in performing the tasks involved in creating and maintaining these systems, subsystems, policies, and procedures must recognize the need to change and then create a shared view of how to change their systems, subsystems, policies, and procedures.

To change quickly (i.e., to be responsive), the company must have methods that identify the need to change. It must have methods that allow it to identify problems. And, it must have methods to allow it to solve the problems and disseminate the solutions throughout the company.

There are multiple tools to identify problems and suggestions for change. The point here is that for a company to learn, it must have in place these systems to support problem identification and learning. These include techniques such as an employee suggestion system and training programs such as training within industry.

… it is vitally important that organizational leaders have a good understanding of human motivation. Each person is a unique individual, and what will cause one to be excited may create fear in another. (Okes and Westcott 2001, p. 25)

Earlier, we explained the importance of empowering an employee to take action to satisfy the customer and the importance of the employee engaging in continuous learning. However, there is one problem with authority—it brings responsibility, which some people would like to avoid. This is important for you as manager and also for the line worker. It is important for you to remember that through your authority you also have a responsibility not only to business objectives but also to the people you are managing. This is important when considering how to motivate people and is an important aspect of Leadership.

Empowering people and giving them authority is not enough. The next step is to understand how to motivate employees to use their knowledge, and how to share their knowledge.

Employees’ motivation to perform tasks is due to both intrinsic and extrinsic motivational factors. Intrinsic task motivation is generally considered to be more motivational than extrinsic motivation. Both the extrinsic and intrinsic motivation are important in the work design. However, in a large organization the extrinsic motivational factors such as the reward structure are outside the control of the middle manager, who may be in charge of the work design, so we are focused here on the intrinsic task motivation factors, which the middle manager is often able to influence as part of the work design. Intrinsic task motivation is often implemented in practice by organizing employees into teams. The teams may be organized differently, but in general they consist of self-directed work teams, which have a defined level of control over a shared set of tasks. Each employee on the team has responsibility not only for performing tasks that advance the work (e.g., installing an item onto a subassembly) but also for ensuring quality and safety and for performing administrative tasks such as scheduling vacation and training for the team members. The team processes enhance the employees’ perceptions of the impact and meaningfulness of their work as well as their sense of competence and allows them self-determination within these prescribed limits.

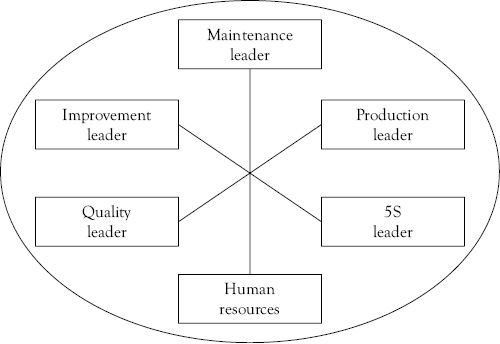

Both intrinsic and extrinsic motivation can be provided to the frontline employee by developing an appropriate team structure to implement. The team structure has to give the employee both explicit responsibilities and the authority to implement those responsibilities as well as provide the employee recognition. Figure 7.3 provides one example of how this can be done. In this example, each team member is given a designated responsibility. For example, the maintenance leader’s responsibility requires the team member to ensure all preventive maintenance tasks are performed each day. This worker also maintains contact with the maintenance employees and ensures the equipment operating measurements are taken and recorded correctly.

The responsibilities inherent in the position can also be made more explicit by providing each team with a matrix—as depicted in Table 7.1— showing the responsibilities of each leadership position. This checklist makes it easier to train the team leader and helps to make explicit the tacit understandings that allow one team leader to perform better than another. It gives clear responsibility to each team leader and the use of measurement means that they receive recognition for tasks done or not done. In addition, it develops leadership skills in the team.

Figure 7.3 Example of responsibility structure on a self-directed work team

Table 7.1 Example of responsibility check list

| Team leadership area | Task | Target | Measurement |

| Maintenance | 1. Assign responsibility to other team members for hydraulic and grease point checks |

Each point has one member assigned | Maintenance checklist shows assignment |

2. Daily check that assigned hydraulic and grease point checks are completed |

Completed before start of shift | Initialed checklist by team leader |

The intrinsic task motivation of the employee is often viewed using the four dimensions of empowerment. These dimensions are:

Sense of Impact: A sense of impact means that the employees feel the task they are performing is important to the completion of the entire work. This is usually operationalized as knowledge of results, so it is important that the employees individually see how their work contributes to the final product.

Competence: Competence is the worker’s feelings of confidence that they are fully qualified to perform the required tasks correctly.

Meaning: Meaning is the match or fit between the work being performed and the individuals own values and beliefs. This is very individual, but it can be developed further by the supervisor engaging the employee in a discussion about the meaning of the task and its relevance to the employee.

Self-determination: Self-determination is the employee’s ability to makes choices about how to perform a task.

Examining the responsibilities given to employees through the team structure using these four dimensions shows that by assigning each member of a team a leadership area we provide a sense of impact, job meaning, and self-determination. The employee is able to recognize that if they do not fulfill their responsibility, their team will not perform as well. The employee is also better placed to see how the work they are doing affects others not only on the team but also on teams that are their customers. Finally, the employee has some ability to decide how they will perform their tasks and how to get others on the team to perform their tasks. A sense of competence is obtained by the worker as they are trained in how to perform their leadership task and the team tasks. As they perform these over time, their confidence in their ability increases.

Leadership

There are two theories. One says, “there’s a problem, let’s fix it.” The other says “we have a problem, someone is screwing up, let’s go beat them up.” To make improvement, we could no longer embrace the second theory, we had to use the first. (Repenning and Sterman 2001, p. 82)

Not one of choosing but of generating, of generating a clear and adequate formulation of what the problem situation “is,” of creating from a set of incoherent and disorderly events a coherent “structure” within which both current actualities and further possibilities can give an intelligible “place”—and of doing all this, not alone, but in continual conversation with all the others who are involved …. (Shotter 1993, p. 150) as quoted in Weick (1995, p. 9)

A leader at work is one who gives others a different sense of the meaning of that which they do by recreating it in a different form, a different “face,” in the same way that a pivotal painter or sculptor or poet gives those who follow him (or her) a different way of “seeing”—and therefore saying and doing and knowing in the world. A leader does not tell it “as it is”; he tells it as it might be, giving what “is” thereby a different “face.” … The leader is a sense-giver. (Thayer 1988, pp. 250–54), as quoted in Weick (1995, p. 10)

The critical point—and the one that takes the most time to ensure—is that top management must have both a clear understanding of the issues and the zeal needed to carry through to the end. More important than anything else is securing the understanding and consent of everyone in the plant, especially of the people on the production floor. Indeed, that is the key point that will determine ultimate success or failure. (Shingo 1989, p. 224)

These quotations about the role of the leader are meant to convey that the role of the leader is very important in a lean environment. Empowerment does not mean that leadership is not important. Actually, with empowerment leadership becomes even more important. The leader has to guide and coach the employees. The manager as a leader does not choose a path, but instead, as Shotter previously says, must generate a structure that allows an ongoing conversation with everyone involved in the work place.

Here we discuss the role of the leader by separating leadership into three categories based on the position of the leader in the organizational hierarchy.

The top level or the system leaders are responsible for formulating the strategy of the organization including directives on organizational policies and goals. These policies and goals are typically general and abstract creating the framework for the organizational structure through directives or policies for each of its parts.

The middle level of leaders or middle management aligns the policies and goals of their units with the directives or policies and goals received from the upper management, creating the organizational structure for their unit.

At the lowest level of the hierarchy, the leaders who directly supervise line workers or front-line employees rely on the organizational structure to keep the organization operating effectively and use routines to solve problems.

Different skill sets are dominant at each level of leadership. The system leader needs higher levels of conceptual (coordinating and integrating) skills. The middle manager requires high levels of human ( understanding and motivating individuals and groups) skills. The direct supervisor or leader requires more technical (performing technical activities) skills. This does not mean that the system leader does not need any human or technical skills, but it does mean that their, and thus the organization’s, success depends more on their conceptual skills than technical skills.

Consequently, each level of leadership has different critical tasks to perform. It is critical for the systems leaders to modify and clarify the company’s goal or mission as the environment and the customer need change to support the company’s effort in creating strategy and policies to modify the overall organization design and the subsystem design. The middle management or organizational unit leader has to integrate the subsystems with each other and develop plans to achieve the company’s goals or mission using the subsystems. The direct leaders are responsible for administering the operating procedures and practices that were developed to accomplish the goals that have been delegated to their subsystem. To do this the direct leaders must maintain and develop the required skills themselves and work with the people, who are reporting directly to him to develop the required skills.

Example: The various roles of the leader at different levels in the organizational hierarchy can be seen during the leaders’ gemba walks (i.e., when the leader walks through the production or service facility). The purpose of the gemba walk is for the leader to understand what is being done and to coach the workers and lower level managers on how to improve the process. For example, when the front-line supervisor is walking through the workplace, they should be checking to see if each team and individual worker is performing the tasks by following standard operating procedures. The front-line supervisor should also be asking about improvements when the department manager walks through with the supervisor. The department manager should be checking that the supervisor has checked that the standard operating procedures are being followed. The department manager does this by looking at one or two teams on how they follow standard operating procedures. The department manager should also be looking to engage the supervisor in conversation for possible improvements. The value stream manager or process manager walks through with the supervisor and the department manager. The value stream manager checks whether the supervisor and the department manager are checking the use of standard operating procedures, and should also be asking questions of the department manager to engage in continuous improvement.

References

American Heritage. 2007. The American Heritage College Dictionary. 4th ed. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin Co.

Grant, R.M. 1996. “Prospering in Dynamically-Competitive Environments: Organizational Capability as Knowledge Integration.” Organization Science 7, no. 4, pp. 375–87.

Ohno, T. 1988. Toyota Production System: Beyond Large-Scale Production. Published in Japanese by Diamond, Inc., Tokyo, Japan, 1978. Translation into English by New York, NY: Productivity Press.

Okes, D., and R.T. Westcott, eds. 2001. The Certified Quality Manager Handbook. 2nd ed. Milwaukee, WI: ASQ Quality Press.

Repenning, N.P., and J.D. Sterman. 2001. Nobody Ever Gets Credit for Fixing a Problem that Never Happened. California Management Review 43, no. 4, pp. 64–88.

Shiba, S., and D. Walden. 2001. Four Practical Revolutions in Management: Systems for Creating Unique Organizational Capability. Cambridge, MA: Productivity Press and Center for Quality of Management.

Shingo, S. 1989. A Study of the Toyota Production System from and Industrial Engineering Viewpoint. 1st revised ed. Cambridge, MA: Productivity Press.

Spear, S., and H.K. Bowen. 1999. “Decoding the DNA of the Toyota Production System.” Harvard Business Review, September–October, pp. 97–106.

Stalk, G., Jr., S. Stephenson, and T. King. 1996. “Searching for Fulfillment: Breakthroughs in Order and Delivery Processes in the Auto Industry.” Discussion Paper, The Boston Consulting Group, as cited in Fujimoto, T. (1999). The Evolution of a Manufacturing System at Toyota. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Weick, K.E. 1995. Sensemaking in Organizations. 1st ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.