CHAPTER 1

Lean Work Design

Work design is defined as the system of arrangements and procedures for organizing work.

Lean Work Design, the title of our book, integrates two concepts: lean operations and work design. There are many definitions of Lean in the literature. In this book, we use a definition proposed by Hopp and Spearman (2004)—a system is lean if it is able to buffer throughput against variance at minimal buffering costs. These buffering costs are the costs of having an inventory buffer, a capacity buffer, or a lead time buffer. A lean system ensures throughput at minimum cost—this means that a lean system realizes operational excellence.

Lean is about achieving operational excellence and is emerging as a body of knowledge because of the success of the Toyota Production System (TPS). To achieve operational excellence, the design of work within the system (i.e., the work design) must not only ensure that individual activities achieve operational excellence but that these activities help the system achieve operational excellence. Indeed, the Shingo Prize for Operational Excellence (www.shingoprize.org), which is named in honor of Shigeo Shingo, who is credited with developing many components of TPS, does not use the word “lean” in its guidelines. Instead the Shingo prize focuses on principles for achieving operational excellence.

Work design is not a job design. Work design considers all the activities that are required to provide a service or a product, while job design focuses on the individual tasks or jobs. Most work is so complex that it is subdivided into tasks performed by different people within different functions and possibly within multiple companies. These people and functions must interact with each other to competently complete the work. This book on Lean work design is concerned with identifying the principles of operational excellence to use to design interactions between those involved in the work process of a product or service so that excellence is achieved.

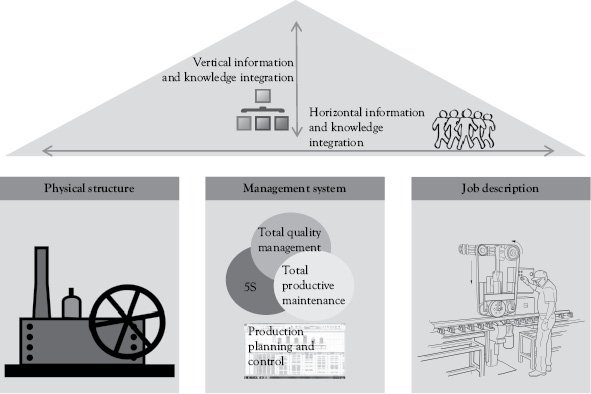

The work environment is complex and many decisions have to be in place to effectively manage work. This includes decisions on the physical structure, the management system, the job description, and how information and knowledge are integrated in the company as shown in Figure 1.1. In the figure’s roof, which determines how a company communicates information and knowledge, an organizational structure is put in place that determines how people will interact with each other while they perform the tasks that are needed to complete work. This organizational structure affects both the vertical and horizontal flows of information and the ability of the organization to integrate knowledge. The main decisions included in the work design are summarized in Figure 1.1.

Decisions about the work design determine the systems that are needed to support the work as well as how the work itself will actually be done. Decisions must be made about the physical structure, the supporting management systems and the job descriptions of the individual jobs within the system as well as the positions that provide support to frontline workers. Even simple tasks require the support of a system to be effective.

Figure 1.1 Main decisions of work design

Example: A department store decides to offer free gift wrapping to customers to encourage sales. The manager designs how this will be done by deciding where to physically perform the work, what equipment is needed to do it, and how this equipment should be positioned in the available space. These are decisions about the physical structure. The manager also has to consider the management system and ensure that it includes a system to provide supplies and labor to staff the gift wrapping station, as needed. The manager has to decide on the standard procedures for performing the work and whether the staff will perform multiple functions or only wrap gifts. These decisions create the actual job design, that is, how the tasks or operations will be performed.

These decisions occur at multiple levels of the hierarchy and influence the physical structure and managerial system, as well as the individual job design. Through their design decisions, managers influence the decisions of everyone else in the organization. For example, these decisions determine which communication channels are natural to use, which information will be shared, and what decisions a worker is allowed to take without previous authorization by upper management. All these decisions must be carefully taken to allow for a competent execution of the task by the worker.

Lean work design is concerned with the entire design of a system and its interacting elements and how that contributes to operational excellence in accomplishing work. The work design is a fundamental set of decisions that determine what processes are in place, which in turn affects the behaviors of departments and individuals in the organization and ultimately determines the organization’s productivity. The following example illustrates how decisions about the organizational structure (e.g., which divisions and departments are created) influence how the work itself will actually be done. For example, the organizational structure decisions affect what coordinating and supportive actions management will take as well as what they will establish as goals, targets, metrics, rewards, and incentives.

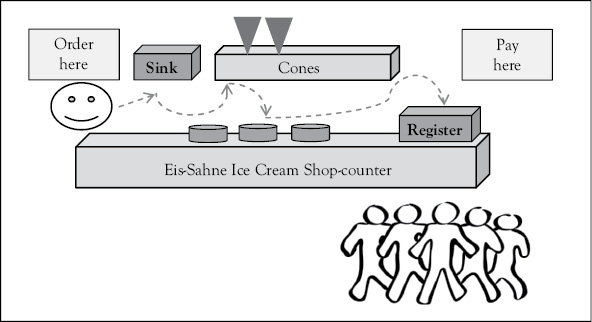

Example: The Eis-Sahne Ice Cream shop is designed so that the customer enters and walks up to the counter where a sign says: “Order Here.” When a clerk is free, the clerk walks to the spot and asks: “What do you want today?” The customer then selects items from the menu, while the clerk records this on a piece of paper. When it is recorded, the clerk repeats it back to the customer and if it is confirmed, the clerk asks the customer to walk to the “Pay Here” sign at the end of the counter. The clerk then walks to the sink, rinses his or her hands, picks up an ice-cream scoop, selects the type of cone the customer ordered, and walks to the location where the type of ice cream the customer requested is stored. The clerk slides the door of the ice-cream cooler to the side, bends over, and scoops up the correct amount of ice cream and places it in the cone. When this is completed, the clerk walks to the “Pay Here” window and places the cone into a cone holder. The clerk enters information about what the customer ordered into the cash register and tells the customer the price. The clerk waits while the customer gets money to pay out of their wallet and gives it to them. The customer then waits while the clerk makes change, prints off a receipt, and then hands it to them. Then the customer takes the cone from the cone holder and leaves the shop.

The preceding work design for the Eis-Sahne is illustrated in Figure 1.2. The work performed in this ice cream shop is relatively simple, but still illustrates how a manager’s decisions about the work design affect the level of operational performance that can be achieved. In this example, the clerk’s work is to provide the ice cream that the customer wants. To do this, the smiley-faced clerk in Figure 1.2 typically follows the path shown by the dashed line each time an order is filled. To serve one customer the clerk typically walks the path that is shown by the dotted line. The clerk starts at the counter, walks to the sink, then to where the cones are stored and from the cone storage to the ice-cream counter. Once the clerk scoops out the correct amount of ice cream and puts it into the cone, the clerk goes to the cash register to take the customer’s money.

This work design is the result of four sets of decisions that the store manager made:

Figure 1.2 Work design of the Eis-Sahne Ice Cream Shop

The manager determined the physical structure of the shop. This could be done by designing a new building, or by locating the shop within an existing physical space. However, the choices about the space affect the flow of the work. The manager also provides physical support to the clerk engaged in the actual service delivery by providing the server with the supporting tools (e.g., the scoop) and equipment (e.g., the cash register and ice-cream cooler).

The manager determined the management system by giving a set of customer service targets to the clerk and how they are controlled. First, the manager established performance measures and targets for performance. Common service targets include the greeting of a customer within 30 seconds of their arrival in the store. Another common example is to set a total service time for the customer. For example, a target might be that customer orders are fulfilled within 2 minutes from the time they are given to the clerk. Other decisions about the management system include establishing a method of ordering more ice cream, a method of balancing labor staffing with customer demand, as well as keeping the shop clean and ensuring security.

The manager created a job description for each position in the system. The job description would include a list of the various work tasks that the worker is responsible for. A more detailed list of work instructions would provide the specific task sequence for a particular service. For example, the work instructions to prepare an ice-cream cone might be simply a detailed list of the steps required by the clerk to prepare a specific type of ice-cream cone for the customer.

The manager established methods to share information and knowledge throughout the work system. For example, how will managers learn the number of customers coming in to the store each hour? How will managers learn the product mix that most appeals to customers? How can orders of more ice cream be processed and paid for? How can the manager ensure that the equipment is being maintained?

As the company provides a more complex set of products and services, the overall work design becomes more complex. However, no matter how complex the overall work being performed becomes, the work design must integrate both the actual work and coordinate the work performed by individuals or individual departments so that there is a smooth flow of materials and services. To do this, lean work design often focuses on simplifying the performance of the work at each stage of the work.

Lean work design considers the same work design components as any other type of work design. The difference is that as lean managers pursue operational excellence they recognize that their decisions about the work design affect the ability of the system component to contribute to operational excellence. Decisions about lean work design are made to ensure that each component of the system contributes to the operational excellence of the system. To achieve operational excellence in a demanding environment, the work design must include respect for the humans operating within the system. Lean work design recognizes that the tasks performed, the equipment used, and the humans in the system are all part of an interacting system.

Many companies face a paradox. On the one hand there is an increase in the number of tools and techniques for improving performance while on the other hand there has been little improvement in the capability of firms to implement these innovations. Repenning and Sterman (2001) suggest that this is due to the inability of managers to think in terms of systems, which means they are not able to see their firm as an organic whole:

Most importantly, our research suggests that the inability of most organizations to reap the full benefit of these innovations has little to do with the specific improvement tool they select. Instead, the problem has its roots in how the introduction of a new improvement program interacts with the physical, economic, social, and psychological structures in which implementation takes place. In other words, it is not just a tool problem, any more than it’s a human resource problem or a leadership problem. Instead it is a systematic problem, one that is created by the interaction of tools, equipment, workers and managers. (Repenning and Sterman, 2001, p. 66)

We view lean as a management method that requires managers to begin “to see” the entire system. Lean requires managers to examine the effects of decisions and seek a deeper understanding of the relationship of the various decisions. The ability of a firm to achieve operational excellence is determined by a large number of short-term decisions. But, to be effective these decisions must be equally interpreted across the organization and lead to concerted actions to achieve the organizational goals.

Is Lean Just an Updated Ford?

Finally you may ask: How do lean operations (i.e., TPS) differ from Fordism? Henry Ford was famous for introducing the assembly line and for emphasizing efficiency by eliminating waste. In his book Henry Ford stated his philosophy of production (Ford 2003):

Efficiency is merely the doing of work in the best way you know rather than in the worst way. …. It is the training of the worker and the giving to him of power so that he may earn more and have more and live more comfortably. (p. 5)

Our own attitude is that we are charged with discovering the best way of doing everything, and that we must regard every process employed in manufacturing as purely experimental. If we reach a stage in production which seems remarkable as compared with what has gone before, then that is just a stage of production and nothing more. (p. 48)

Taiichi Ohno, the vice-president of Toyota, who is credited with creating many of the components of the lean work design, states that a major difference between Ford and Toyota is that while both emphasized improving the efficiency of the work flow, Toyota also emphasized eliminating the warehouse by reducing setup times and using small lot sizes. Ford sought to reduce the unit cost by producing in large quantities, so that the cost of the setup was spread over many units. Ohno discusses these differences in many places in his book even as he discusses the similarities between Toyota and Ford (Ohno 1988).

Why are we so different from—in fact, the opposite of—the Ford system?

For example, the Ford system promotes large lot sizes, handles vast quantities, and produces lots of inventory. In contrast, the Toyota system works on the premise of totally eliminating the overproduction generated by inventory and costs related to workers, land, and facilities needed for managing inventory. (p. 95)

Which is the superior position, the Ford system or the Toyota system? Because each is undergoing daily improvement and innovation, a quick conclusion cannot be drawn. I firmly believe, however, that as a production method the Toyota system is better suited to periods of low growth. (pp. 96–97)

I, for one, am in awe of Ford’s greatness. I think that if the American king of cars were still alive, he would be headed in the same direction as Toyota. (p. 97)

We see in Ford’s thinking his strong belief that a standard is something not to be directed from above. Whether it be … top management, or a plant manager, the person who establishes the standard should be someone who works in production. … And I agree. (p. 99)

Here, the foresight of Ford is revealed clearly. We see that automation and the work-flow system invented and developed by Ford and his collaborators were never intended to cause workers to work harder and harder, to feel driven by their machines and alienated from their work. (p. 100)

Ford’s successors, however, did not make production flow as Ford intended. … A major reason is that Ford’s successors misinterpreted the work flow system … I think they were forcing the work to flow. (p. 100)

These quotes from Taiichi Ohno and Henry Ford suggest that Repenning and Sterman (2001) are correct. To be successful, a work design must solve the problems due to the interactions of the physical, economic, and human issues in the work place. Again, the purpose of this book is to explain how lean work design can be used to solve these interaction problems in a systematic manner toward reaping the full benefits of lean operations.

References

Ford, H. 2003. Today and Tomorrow: Commemorative Edition of Ford’s 1926 Classic. Originally published by Doubleday, Page & Company. Reprinted, Boca Raton, FL: Taylor & Francis Group, LLC, CRC Press.

Hopp, W.J., and M.L. Spearman. 2004. “To Pull or Not to Pull: What Is the Question?” Manufacturing & Service Operations Management 6, no. 2, pp. 133–48.

Ohno, T. 1988. Toyota Production System: Beyond Large-Scale Production. Published in Japanese by Diamond, Inc., Tokyo, Japan, 1978. Translation into English by New York, NY: Productivity Press.

Repenning, N.P., and J.D. Sterman. 2001. “Nobody Ever Gets Credit for Fixing a Problem that Never Happened.” California Management Review 43, no. 4, pp. 64–88.

Sinha, K.K., and A.H. Van de Ven. 2005. “Designing Work Within and Between Organizations.” Organization Science 16, no. 4, pp. 389–408.