CHAPTER 4: WHY DID NOBODY WARN US?

“Diseases know no boundaries. They threaten us all.” Former US President Clinton, 1996 (WP, 2020)

The truth is, we had been warned – on numerous occasions and from several different sources. I guess maybe not many people were listening in either government or business circles around the world. Very few people in the workplace today will have lived through a serious pandemic. Consequently, I believe the truth is that before the SARS-CoV-2 virus arrived, many were living in a state of ignorance or denial.

“At some point, we are likely to face another pandemic.”

George W Bush, 1 November 2005 (WP, 2020)

Long before he became US President, Barack Obama was endeavouring to raise the profile of the pandemic threat. In 2005 he said:

“When we think of the major threats to our national security, the first to come to mind are nuclear proliferation, rogue states and global terrorism.

But another kind of threat lurks beyond our shores, one from nature, not humans – an avian flu pandemic. An outbreak could cause millions of deaths, destabilize Southeast Asia (its likely place of origin), and threaten the security of governments around the world.”

Barack Obama, 2005 (McLeigh, 2017)

Two years earlier, the speed at which SARS had proliferated across 26 countries should have started alarm bells ringing. Furthermore, in 2012, a second emerging and potentially fatal coronavirus, MERS, ought to have complemented any cacophony that SARS had managed to create. However, it seems that only some of those countries in Asia that had found themselves caught in the ‘crosshairs’ of SARS and MERS actually sat up and took notice.

In 2005, The New York Times published an article jointly written by Barack Obama and Richard Lugar in which they quoted Dr Julie L Gerberding. She was, at the time, the Director for the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. In referring to the possibility of an avian flu identified as H5N1 spreading from South East Asia, Dr Gerberding said:

“A killer flu could spread around the world in days, crippling economies in Southeast Asia and elsewhere. From a public health standpoint, Dr. Gerberding said, an avian flu outbreak is “the most important threat that we are facing right now.”.” (Obama & Lugar, 2005)

Originally identified in 1976, the 2014-2016 West Africa Ebola outbreak was contained. This was thanks to thousands of selfless health workers. A global spread of the disease was avoided, but not before more than 11,000 had died. It was while this outbreak was in full flight in 2015 that Bill Gates gave the TED talk entitled “The next outbreak? We’re not ready”. Did no one see and react to this talk? According to the TED website, around 43 million did view the recording, while the YouTube posting of the talk has at this time of writing, logged a further 36 million views. So, did no one take Bill Gate’s warning seriously?

Other warnings have come and gone, and have been largely ignored, except perhaps by the medical profession, which knows only too well the health implications of a severe pandemic.

4.1 The coronavirus family

Coronavirus was first discovered by the Scottish virologist, Dr June Almeida, in her laboratory at St Thomas’ Hospital, London in 1964. The virus owes its name to the crown or halo that surrounds it, which Almeida observed through an electron microscope (Brocklehurst, 2020).

The CDC has listed seven coronaviruses that can infect humans, although four, 229E, NL63, OC43 and HKU1 only result in relatively mild symptoms. However, the remaining three SARS-CoV, MERS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2 can be fatal to humans and have all been identified since the start of the new millennium (CDC, 2020).

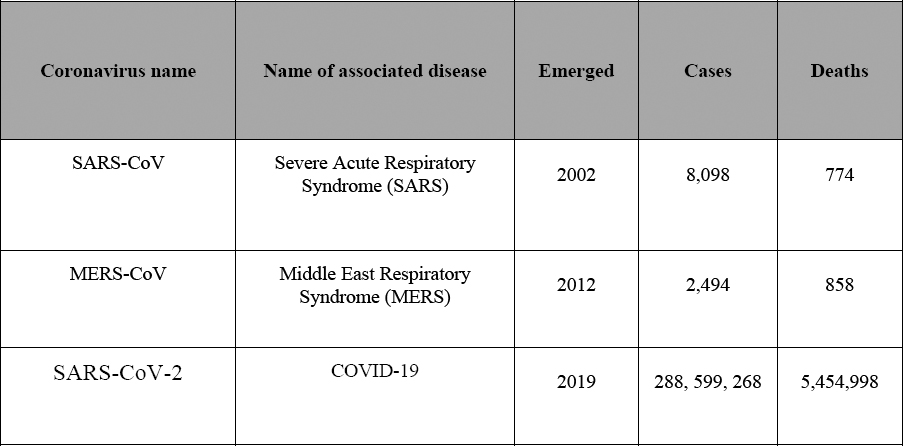

Although COVID-19 has spread globally, SARS and MERS only reached 26 and 27 countries respectively. Their mortality rates also differ, with MERS measured at 34.4%, SARS at 9.50% and COVID-19 the lowest of the three coronaviruses at 5.06%.

Figure 24 provides a snapshot comparison of these three coronaviruses, although, at the time of writing, the world was still very much in the clutches of the COVID-19 disease.

Figure 2: SARS, MERS and COVID-19 statistical comparison

The three conditions present similar symptoms, although COVID-19 can affect different people in different ways. Some will be asymptomatic, but most infected people will develop mild to moderate illness and recover without hospitalisation. Those typically presented symptoms might include, although are by no means limited to, fever, dry cough, tiredness and breathing difficulties. As we have learned more about COVID-19, more symptoms have been identified. For an up to date list, please refer to a credible source, such as the WHO, CDC or your national disease control centre, such as Public Health England, ECDC, China CDC and African CDC, etc.

For some people, COVID-19 results in symptoms that last for weeks or even months after the infection has gone. Often referred to as post-COVID-19 or ‘long COVID’, the typical symptoms are not dissimilar to COVID-19 itself. As in the previous paragraph, for an up to date list of these symptoms, please refer to one of these reliable sources.

What the world cannot afford to overlook, is the frequency with which these potentially fatal coronaviruses have appeared since the arrival of the new millennium. Ten years between SARS and MERS, followed by seven years between MERS and COVID-19. Does that mean that we can expect another coronavirus to appear on the scene during the current decade?

4.1.1 Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS)

“Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) is the first new disease to show the damage possible in a globalized world.”

(Mary Kay Kindhauser, WHO, 2003), (Clark, 2016, p43)

The virus, SARS-CoV, which causes the severe acute respiratory syndrome, was the first novel virus and wake-up call of the new millennium. It demonstrated how quickly a novel virus could spread across the world assisted by modern commercial aviation. It was spreading even before the WHO knew of its existence.

SARS originated in Guangdong province in China in November 2002, although initially the Chinese authorities treated the situation as a state secret. Consequently, when it spread to Hong Kong in February 2003 and from there on to Singapore, Hanoi, Toronto and Taiwan, people erroneously believed that Hong Kong was the initial source (Feeney, 2014).

SARS was contained by isolating the infected and quarantining those believed to have been exposed to the disease. In Toronto, 25,000 were quarantined and 18,000 in Beijing. At least this lesson was not wasted, and has been employed again in dealing with COVID-19. Even so, when the numbers quarantined during the SARS outbreak are compared with the many millions of people quarantined as entire cities were locked down in response to COVID-19, SARS almost fades into insignificance. However, there is still no known cure or a vaccine available for SARS, so a comeback is not beyond the realms of possibility.

“The psychological reaction in Hong Kong was the generation of fear, panic and paranoia. Moreover, putting the situation into context, of the 7,000,000 inhabitants of Hong Kong, less than 2,000 were infected with SARS and around 300 died. That represents less than 0.029% of the population who actually caught the disease. Even so, approximately 80% of the population took to wearing face masks, in what some have called an unnecessary knee-jerk reaction.”

(Clark, 2016, p 74)

In just a few months, SARS is known to have infected less than 10,000, with 776 recorded associated deaths. Despite this, it was referred to as an economic tsunami and cost the global economy an estimated $50 billion (TASW, 2011).

In Hong Kong, tourism, hospitality and retail industries were all badly affected, along with their supporting industries and associated supply chains. Airlines cancelled flights to and from the territory, as passenger numbers plummeted by as much as 77% in April 2003. Hong Kong-based carrier, Cathay Pacific, went from reporting a $505 million 2002 operating profit to losing $3 million per day.

Nervous customers were staying away as restaurants, bars and cinemas generally remained empty, while the wearing of protective face masks became the norm. Between March-May 2003, average hotel occupancy rates dropped from 79% to 18%, which necessitated some drastic action. Among the more elite hotels:

• The Hyatt Regency sacked 130 staff, while another 470 staff took ten days unpaid leave per month.

• The Grand Hyatt closed some floors and all staff had to take unpaid leave.

• In the Regal Hotel Group, every employee in its five hotels took eight days unpaid leave per month.

• At the Marriott, voluntary unpaid leave was encouraged. The CEO took the month off as a ‘leading by example’ show case.

(Lee & Warner, 2008)

“The world should brace itself for an increase in infectious diseases like SARS because of a fatal underestimation of the power of viruses and bacteria …

“Humans tampered with the environment to the extent that the effects were now being seen in the form of mutated viruses.

“I believe that the next ten to 15 years will see a substantial increase in infectious disease,” Prof Curson said.”

Professor Peter Curson, Historical Epidemiologist at Sydney’s Macquarie University (Curson, 2003)

Of the many novel diseases discovered since the end of World War II, if we only consider the three potentially fatal coronaviruses that have emerged this century, Curson’s prediction has so far proved remarkably accurate. In 2012, ten years after SARS, the Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS) was identified, and COVID-19 followed seven years later.

4.1.2 Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS)

Unlike SARS and COVID-19, which were first identified in China, MERS is believed to have originated in Saudi Arabia. It is also likely to be the least well-known of the three. Compared with its two coronavirus relations, MERS is rare, and well under 3,000 cases have been diagnosed since it emerged. Although cases have been recorded in 27 countries, it is most common in the Middle East.

Sometimes referred to as ‘camel cough’, as it is believed to be carried by camels, its symptoms are similar to SARS and COVID-19, and it can be transmitted from human to human by cough droplets. Approximately one-in-three cases prove to be fatal.

In 2015, there was an outbreak in South Korea, which has, to date, been the largest outbreak outside of the Middle East, with 185 cases diagnosed and 38 deaths. Having faced both outbreaks of SARS and MERS, South Korea is certainly one country that appears to have been better prepared to deal with COVID-19.

While MERS has not spread with the same intensity of either SARS and especially COVID-19, it did provide the world with another reminder that emerging diseases should be taken seriously.

4.1.3 SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19)

As I write, we are in the middle of a pandemic, and COVID-19 is the here and now. Hardly a day passes when we do not learn something new about the disease.

Like SARS and MERS, we know that the symptoms are similar, and it can be transmitted from human to human in the same way. However, two symptoms not presented by SARS or MERS patients have been noted – loss of taste and smell. We also know that, unlike SARS and MERS, it is more than just a respiratory infection, and, as a multi-systems disease, it can attack just about any organ within the body.

We have also learned that it can leave infected patients with scarring on the lungs, along with possible side effects on the heart and kidneys, and it may even have a neurological legacy, too. The UK Sepsis Trust is concerned that COVID-19 survivors could subsequently develop sepsis. This condition can be triggered when the body overreacts to an infection, causing the immune system to turn on itself – leading to tissue damage, organ failure and potentially death.

In August 2020, the UK’s Office of National Statistics (ONS) published a report possibly linking polluted air and COVID-19 mortality. Corresponding studies in the US, Northern Italy and the Netherlands have revealed similar results (ONS, 2020).

For some people, COVID-19 does not present a linear recovery path. In fact, a victim’s recovery time can be significantly prolonged by post-viral fatigue, which in some instances could last for many weeks and delay a return to work. Moreover, evidence has also been found suggesting that Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic (BAME) groups can be twice as much at risk from COVID-19 than the white population. UK scientists are receiving millions of pounds of government funding to research why people from an ethnic minority background are at greater risk from COVID-19.

Clearly, a major priority was to find a vaccine, and more than 100 worldwide laboratories joined the challenge to find a safe and effective solution. What is more, it is as yet unclear whether infected patients gain any long-term immunity once they have recovered from COVID-19. In addition to the search for a vaccine, work has also been focusing on whether any existing medication can help with the treatment of the disease. So far, work in the UK has discovered that the inexpensive and readily available drug, dexamethasone, can speed up recovery time. Remdesivir is also being used in an attempt to accelerate a patient’s recovery from COVID-19.

4.2 H5N1 2006 and H1N1 2009

Although they were mild outbreaks, influenza reminded us it was still around with the avian flu and swine flu outbreaks of 2006 and 2009. The reality is that, scary though many may consider COVID-19 to be, it is possibly just a trial run for the severe influenza pandemic that many NRRs are predicting (see section 4.5).

4.3 Bill Gates – “The next outbreak? We’re not ready”

The Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation works with partners across the globe to tackle five different programme areas. Of specific interest to readers of this book will be the Global Health Division, which aims to reduce inequities in health by developing new tools and strategies to reduce the burden of infectious disease (Gates Foundation, 2020).

In his 2015 Ted Talk, Bill Gates told the audience that when he was a child, the disaster that people worried about most was a nuclear war. But today, a global disaster is much more likely to come from an influenza pandemic than a nuclear apocalypse. If anything is likely to kill millions of people, it is most likely to be a virus.

Gates argued that the world is simply not ready for the next epidemic and he uses the 2014-2016 Ebola outbreak to illustrate the point. Moreover, Ebola was largely contained across three West African countries – unlike COVID-19, which has achieved global proliferation. That said, Ebola was active primarily in rural communities, but had it spread to densely populated areas, the outcome could have been very different. He also adds that the virus could be a natural occurrence or it could be the result of bio-terrorism (Gates, 2015).

4.4 Business Continuity and the Pandemic Threat

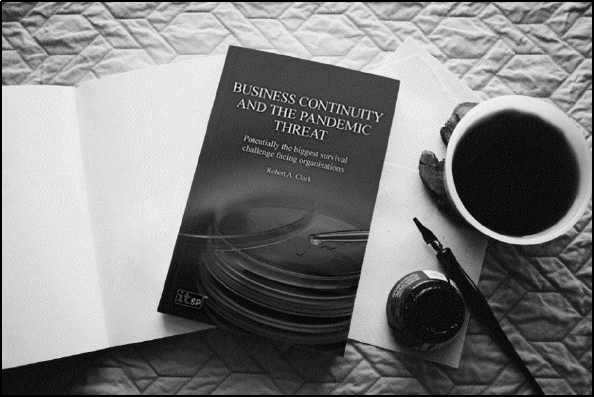

Having already been convinced of the high probability of a severe pandemic occurring, when my own publication first hit the bookshelves in 2016, I did hope that it would add some support to the other pandemic wake-up calls that had gone before. Consequently, I was delighted to discover that the medical fraternity embraced it and were taking it very seriously.

Since its initial launch, to my knowledge, at least two US clinicians have referenced my book in their own publications, Dr Jonathan Quick (Quick, 2018) and Dr Lisa (Koonin, 2020).

In writing the book, I was very grateful for guidance from Dr Martyn Hinchcliffe BM MRCP FRCR and Dr Fergus O’Connor MD FRCS (Lon) FRCS (Edin) who also very kindly said:

“I know you had the business community in mind when you wrote this book, but everyone should read it, it could save lives.”

Figure 3: Business Continuity and the Pandemic Threat – Potentially the biggest survival challenge facing organisations

Sadly, the same was not true of people involved in business continuity or crisis management, who were actually the target audience I originally had in mind. Some thought the subject matter was too morbid. Others just laughed at me and said a severe pandemic was never going to happen. “Don’t worry, the health services have this one covered”, was a typical response.

In July 2017, I also took the opportunity to speak at the Business Continuity Institute’s (BCI) North East forum meeting in Leeds. My presentation was entitled “Is a pandemic potentially the biggest survival challenge facing organisations?”, but disappointingly my talk received a very cool reception.

Even though Business Continuity and the Pandemic Threat ultimately became a bestseller, I have taken no pleasure in being proved right, especially as I watched the daily toll of new cases and fatalities continuing to grow across the world.

Figure 4: There’s going to be a pandemic – you’re having a laugh?

4.5 National risk registers

I have had the opportunity to examine a number of NRRs from different countries over a period that stretches back well over a decade. They all have one thing in common – severe influenza pandemics were seen as the ‘Number One’ threat.

In writing this book, I will refer to the UK NRR of Civil Emergencies (UK NRR) as it is in the public domain and can be downloaded for reference (UK Cabinet Office, 2017). This document is reviewed and republished periodically.

The UK NRR explains that it is difficult to forecast the spread and impact of a new flu strain or new emerging infectious diseases until they start circulating. However, consequences may include up to 50% of the UK population experiencing symptoms, potentially leading to between 20,000-750,000 fatalities and high levels of absence from work.5

If a global estimate is calculated from a simplistic extrapolation from the projected worst case UK scenario, this would result in an approximate global figure in excess of 85 million deaths.

In the context of a pandemic, there are two risks that need consideration, ‘pandemic influenza’ and ‘emerging infectious diseases’ – COVID-19 falls into the latter category.

The UK NRR also warns of the possible spread of vector-borne diseases, such as Dengue, Yellow Fever, West Nile virus and Zika, which are carried by mosquitoes. Except for Zika, they are not known to be transmitted from human to human, they are typically found in the tropics and have previously not bothered countries with temperate climates. However, with the ever-growing threat of global warming, there is evidence that these diseases are already expanding their range both north and south. The aedes aegypti mosquito has already established itself in Florida and other areas, such as the Mediterranean Sea basin, could prove to be an ideal climate, too.

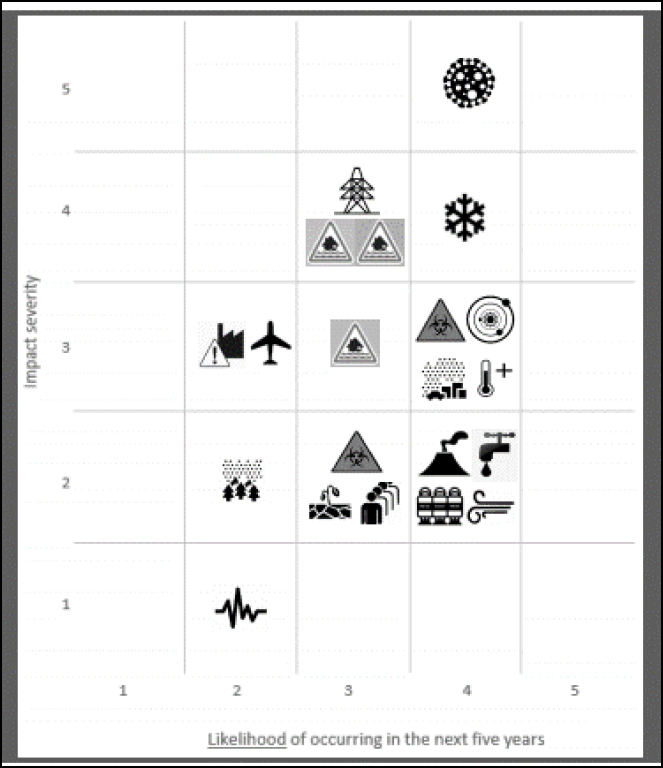

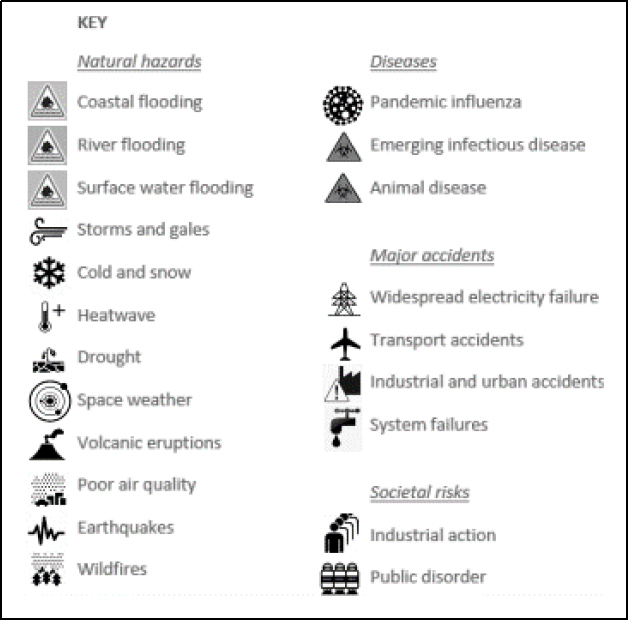

Figure 5: Hazards, diseases, accidents and societal risks (UK Cabinet Office, 2017, p 9)6

Figure 5 illustrates the UK NRR risk prioritisation, while Figure 6 provides the key or legend.

Using a ‘5 x 5’ matrix to calculate the risks in Figure 5, the maximum score possible is 25 (i.e. if you have a risk that scores a ‘5’ for the impact severity and another ‘5’ for the likelihood of occurring, ‘5’ x ‘5’ gives you that maximum score of ‘25’).

Figure 6: Hazards, diseases, accidents and societal risks legend (UK Cabinet Office, 2017, p 9)7

The pandemic influenza risk scores 20 out of 25, placing it in the ‘Number One’ risk position. This is followed in second place by ‘cold and snow’, four points behind. ‘Emerging infectious diseases’, the classification for COVID-19, scores a comparatively much lower score of 12 out of 25. The UK NRR goes on to explain that:

“The emergence of new infectious diseases is unpredictable but evidence indicates it may become more frequent.

This may be linked to a number of factors such as: climate change; the increase in world travel; greater movement and displacement of people resulting from war; the global transport of food and intensive food production methods; humans encroaching on the habitat of wild animals; and better detection systems that spot new diseases.

No country is immune to an infectious disease in another part of the world. In light of evidence from recent emerging infectious diseases such as Ebola and Zika, the likelihood of this risk has increased since 2015.”

(UK Cabinet Office, 2017, p 7)

It is worth noting that the risk value of ‘emerging infectious diseases’ in the UK NRR published in 2015 was 9/25 (UK Cabinet Office, 2015, p 13). In the 2017 UK NRR publication, while the projected impact of ‘emerging infectious diseases’ remains the same as its 2015 equivalent, the probability of occurrence has increased. The relative likelihood of occurring in the next five years increased from between ‘1-in-200 and 1-in-20’ to ‘1-in-20’ and ‘1-in-2’. The events of 2020 have clearly shown this revision of the risk assessment to have been justified.

Adding strength to the UK NRR, in his 2018 publication, The End of Epidemics, Dr Jonathan Quick states that close to 400 new infectious diseases have been discovered in the previous 75 years. This includes HIV/AIDS, Ebola and Zika. He adds that since 1971, scientists have discovered at least 25 new pathogens for which we have no vaccine or treatment. Quick further argues that:

“Given the rate at which population, deforestation, global warming, urbanization, climate change, international travel, and emergence of new pathogens are accelerating the risk of pandemics, it’s reasonable to ask: Are we entering the century of pandemics?”

(Quick, 2018, p 41)

4.6 The fragility of tourism in the face of a pandemic

In November 2018, I was invited to present a paper at the Budapest Business School (BGE) entitled “The fragility of tourism and hospitality in the face of a pandemic”. This invitation was extended to joining the panel discussion on Sustainable Tourism – Best Practices.

With COVID-19 raging around the world, two of the most vulnerable industry sectors have been reeling – tourism and hospitality. There are other industries of course, but these were the two my paper focused on in Budapest.

The World Travel and Tourism Council maintains that tourism directly accounts for 3.2% of the global economy, along with a further 10.4% indirectly. However, some countries are far more dependent on tourism income than others. In the Maldives, almost 40% of its GDP is tourism generated. At 14.2%, Malta is the European country with the highest GDP tourism dependency compared with 3.7% for the UK and 2.6% for the US (Smith, 2020).

Using the lessons learned from Hong Kong’s experience in 2003 with SARS, I was able to relate the type of actions that hotels and restaurants would need to take to stand a chance of surviving a severe pandemic.

Figure 7: Delivering at the BGE

The Sustainable Tourism panel, which followed the seminar, included Catherine Feeney (Edinburgh Napier University), Balazs Kormany (Board member of the Hungarian Hotel and Restaurant Association), Professor Melanie Smith (Corvinus University of Budapest), Robert Clark (Consultant, Trainer and Author) and moderator Dr Németh Tamás (BGE).

The venue was full, thus presenting an opportunity, albeit limited, to promote the threat of a pandemic to the attention of the academia. In a positive response, Dr Sara Csillag, Head of Institute at the BGE, expressed her intent to implement a programme of hygiene across the school, which would need to be one of the key actions required in the event of a pandemic.

4.7 Leading virologist warns top corporations

In 2019, world-expert virologist, Nathan Wolfe, warned top corporations that a severe pandemic could have multi-trillion dollar implications. Unfortunately, the warning seems to have fallen on deaf ears (Machell, 2020).

A similar warning had been previously issued by economist, Dr Sherry Cooper, some 11 years earlier, who stated that the cost to the global economy from even a moderate pandemic would be measured in trillions of dollars.

4.8 International Security Expo – December 2019

I guess the last irony, from a personal point of view, was the International Security Expo, London, which was held in December 2019. I had originally been invited to present a paper entitled “Evaluating the multi-faceted threat from a pandemic that will confront the business world”. By chance, the timing of the Expo coincided with the embryonic stages of what was to become the coronavirus pandemic. Yet, what would have been my last opportunity to address a large audience about the pandemic threat before it actually occurred never happened. The promoters, as was their right, opted for an alternative speaker who spoke about computer viruses instead. Life is so full of irony!!

4.9 So, was anyone really listening to the warnings?

Speaking on the BBC Breakfast programme in April 2020, Bill Gates believes that despite all the warnings most governments were simply not ready for the coronavirus. He also remarked that:

“Very few countries are gonna to get an A-grade for what that scrambling looked like and now here we are, we didn’t simulate this, we didn’t practice so both the health policies and economic policies, we find ourselves in unchartered territory.”

(Gates, 2020)

In October 2019, the world-renowned Johns Hopkins University published its Global Health Security Index. It marked every country out of 100 for its effectiveness across six criterions. In the section measuring ‘Rapid Response to and Mitigation of the spread of an Epidemic’, the UK came top with 91.9% and the US was in second place with 79.7% (Johns Hopkins University, 2019, p 20). The implication of Johns Hopkins’s findings was that the UK and the US were both prepared to react to a pandemic. Ironically, when considering their respective responses to COVID-19, neither country has been a shining example of best practice in managing a pandemic.

Seized by the gravity of the COVID-19 crisis, the World Health Assembly in May 2020 requested the Director-General to review lessons learned from the WHO-coordinated international health response to COVID-19. The Director-General asked Her Excellency, Ellen Johnson Sirleaf and the Right Honourable Helen Clark to convene an independent panel for this purpose. They, in turn, invited 11 highly experienced, skilled and diverse people to form the panel. These include other former heads of government, senior ministers, health care experts and members of civil society. Referred to as The Independent Panel for Pandemic Preparedness and Response (TIP), it spent eight months reviewing evidence of the spread, actions and responses to the COVID-19 pandemic. Although not mentioning either the UK or the US specifically, TIP observed that:

“Country wealth was not a predictor of success. A number of low- and middle-income countries successfully implemented public health measures which kept illness and death to a minimum. A number of high-income countries did not.”

(TIP, 2021)

So, which countries might be in line for that elusive Bill Gates ‘A-grade’? If we consider those countries that experienced SARS and/or MERS, in the main they have fared better than most countries that are experiencing a coronavirus outbreak for the first time.

As I write, the pandemic continues its march across the planet with the Omicron variant currently leading the charge. Consequently, it will only be in the final analysis that we will be able to accurately conclude which countries did well, which could have done better and which were a complete disaster. But, we can look at those countries that have got off to a good start and try to understand why.

A rather important point to remember is that the WHO has not provided any guidelines on how countries should report their COVID-19 cases and related fatalities. Therefore, each country has been left to decide how its figures are presented, and it is not always possible to accurately compare statistics. Moreover, some countries in the developing world do not necessarily have the means to diagnose every COVID-19 case. Charles Parton spent 22 years of his 37-year diplomatic career in China, Hong Kong and Taiwan. Commenting on China’s COVID-19 case and fatality count, he remarked:

“I don’t think anyone believes that the statistics coming out of China are accurate. Clearly politics comes into this and the party wishes to show that it has done a far better job at containing it (the Coronavirus) than it really has.”

(Gracie, 2020)

Russia is another country where case and fatality statistics seem rather out of step. By 9 September 2020, it had declared more than one million cases, but only 18,000 fatalities, circa 1.7% of its total case count. This was seen by many experts as totally implausible. With a global average mortality rate of around 6%, a more realistic Russian death count should have been in the region of 67,000. However, by the end of 2020, The British Medical Journal (BMJ) reported that Russia had come clean. It had admitted that its death toll was more than 180,000, making it the third highest in the world at that time (BMJ, 2020). In fact, by 31 December 2021, Russia had declared around 10 million cases with over 300,000 fatalities. Meanwhile, Iran’s statistics have attracted interest, too. With a declared death toll of 17,000 as of 1 August 2020, leaked official Iranian government papers revealed the actual figure is likely to have been more than 42,000, 2.5 times higher than officially declared. Like Russia, Iran also appeared to be reporting a more realistic figure of 131,606 fatalities as year end 2021 approached.

That said, it does appear that, generally, South-East Asian countries that have had experience of SARS or MERS have made a good start and I would like to focus on three of them.

4.9.1 Hong Kong

I have been a frequent visitor to Hong Kong in recent years, including the time I spent there researching the impact of SARS for my previous pandemic book. What has always impressed me is that it is clearly ready for a pandemic, as a consequence of the devastating effect that SARS had on the territory. As people arrive in Hong Kong, thermal imaging has been used to discreetly measure their temperatures since the SARS outbreak. Many other countries only started doing this after the COVID-19 pandemic materialised.

Some countries’ leaders have been giving out mixed messages regarding whether people should wear masks or not. Even before the pandemic, in Hong Kong, if someone had a cold or some other infection, they automatically wore a mask so as not to pass it on to others. Remember that we should all wear masks to reduce the chance of passing infections onto others.

Walk into a shopping mall and you will see hand sanitising dispensers for peoples’ use. Although public transport and airlines around the world have started regular, deep cleaning, this has been routinely done in Hong Kong since SARS.

Hong Kong is semiautonomous, and it is the fourth most densely populated country or territory in the world, with a population of around 7.5 million. Yet, by mid-July 2020, it had recorded less than 2,000 cases of COVID-19, and around a dozen deaths in the first wave of the pandemic. Seventeen months later, those figures had risen to a comparatively low 12,667 and 213 respectively. I believe the world can learn a lot about managing pandemics from Hong Kong, especially in the way it appears to have used SARS as a dress rehearsal for COVID-19.

4.9.2 South Korea

I have never been to South Korea, and unlike Hong Kong, its experience of SARS was minimal. However, in 2015 it did suffer the largest outbreak of MERS outside of the Middle East. Many companies and individuals looking to purchase face masks for protection during the MERS epidemic found that they very quickly sold out. This was an experience to be repeated in various parts of the world when COVID-19 appeared on the scene. Even so, its highest first pandemic wave daily peak of 851 new COVID-19 cases occurred more than a week before the WHO’s global pandemic declaration on 11 March 2020.

Although its case and fatality statistics are not as impressive as Hong Kong’s, what has caught the attention of many observers is South Korea’s apparent ability to track and trace the spread of the virus.

Four years before the MERS outbreak, South Korea had introduced the Personal Information Protection Act, which imposed strict compliance on any organisation that collects individuals’ personal data. This would typically include mobile phone tracking and credit/debit card transaction recording. However, in the event of a national emergency, government agencies can collect and use this data without needing to seek authority.

“The ability to collect, process and widely disclose personal data has enabled health authorities to conduct contact-tracing with military precision.”

(Chan, 2020)

What sets South Korea apart from other democracies is its willingness to use widely available advanced technology that almost gives it a kind of ‘Big Brother’ persona, normally considered synonymous with totalitarian regimes.

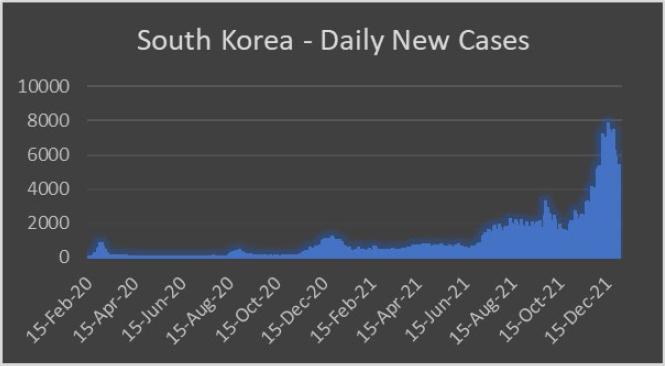

But sadly, South Korea’s 2021 year end assessment presented a worrying development. While previous daily new cases’ statistics had shown the maximum spike size of 3,200 new case diagnoses in October 2021, within two months, a cluster of new cases had appeared with each spiking at more than double the October figure.

4.9.3 Taiwan

One of the six SARS hotspots in 2003, with a population of around 24 million, Taiwan is certainly the country to watch. While some countries have been seeing daily new case counts measuring in the tens of thousands, by year-end 2020, Taiwan had never exceeded 27.

In the eight months since the pandemic outbreak, in a population of almost 24 million, Taiwan has recorded only 817 cases and just 7 deaths. This rose to 17,000 and 850 respectively by December 2021. Its approach has been simple. Initially, the border was closed to non-residents in March 2020. It has since followed a strict quarantine procedure for all arrivals, plus a targeted testing process, coupled with a very efficient contact tracing programme. The population are also complying with social distancing and wearing face masks, resulting in Taiwan, unlike so many other countries, not needing to implement a major lockdown. It did, however, introduce tougher measures by closing entertainment venues and limiting the size of gatherings to deal with a spike in cases between May and July 2021.

4.9.4 The Hare and the Tortoise?

Having mentioned Taiwan, South Korea and Hong Kong in this way, I feel I must add a caveat. We must not forget that we are in a marathon, not a sprint, as each country battles with coronavirus. It will only be after the pandemic is declared ‘over’ that we will be able to look back and make an accurate and fare assessment on how each country has performed.

Despite their excellent starts, whether these three countries will remain among the front runners, achieving one of those coveted ‘A’ ratings that Bill Gates spoke of, remains to be seen. Or perhaps the moral of The Hare and the Tortoise may yet prove to be more appropriate.

So how had these countries fared by year-end 2021?

Figure 8: South Korea – Daily new cases 31 December 2021

For South Korea, after the initial surge of daily new cases at the end of February 2020, Figure 8 illustrates a low steady flow of cases with a modest peak during August and September. Moreover, the maximum number of daily cases in the second peak was only around half the number recorded during the original peak. But by November, things started to go wrong. and we see a massive third wave of new daily cases, peaking at more than 1,200 and then doubling by August 2021. Fuelled by the arrival of the Omicron variant, 2021 ended with South Korea’s daily new case count more than doubling the peaks witnessed some four months before.

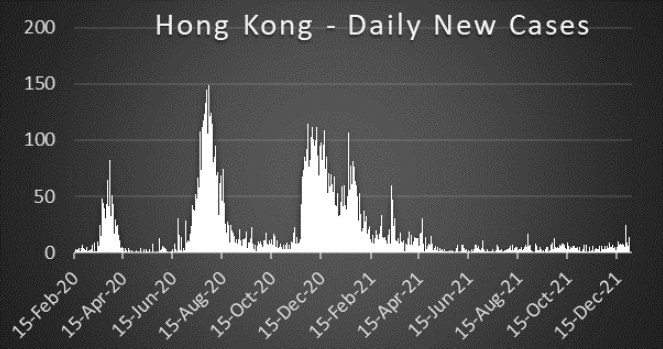

In stark contrast, after a comparatively small first wave that peaked at just 82 new daily cases, Hong Kong presented signs of a much bigger second wave that threatened to overwhelm its health services. Even so, its current peak of 145 daily new cases on 27 July 2020 is still considerably smaller than South Korea’s highest daily figure of 851 registered on 3 March 2020. Moreover, South Korea has registered 4.4 times as many deaths as Hong Kong.

Figure 9: Hong Kong – Daily new cases 31 December 2021

Despite the comparatively modest daily new case count peak, the BBC reported that:

In a statement on 29 July 2020, the Chief Executive of Hong Kong, Carrie Lam, warned the local population that the city was on the “verge of a large-scale community outbreak, which may lead to a collapse of our hospital system and cost lives, especially of the elderly.” (BBC News, 2020)

Like South Korea, Hong Kong had also experienced a third peak before year-end 2020, although its peak was lower than the second wave, reaching only just over 100 daily new cases.

An interesting comparison can be made between Hong Kong, France and the UK. The populations for each of the two European countries are approximately nine times greater than Hong Kong’s. But as of 15 October 2020, the highest daily new case counts for France and the UK were 206 and 136 times greater respectively than Hong Kong’s highest peak of 149. On a population count pro-rata comparison, Hong Kong was in a considerably much better position than either France or the UK.

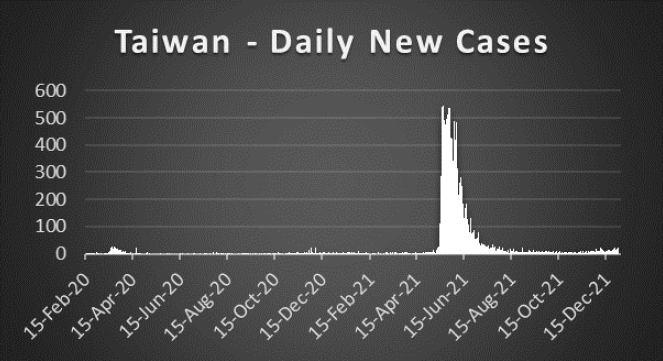

But still very much on course for that elusive ‘A’ grade that Bill Gates talked of is Taiwan.

Figure 10: Taiwan – Daily new cases 31 December 2021

Apart from a handful of minor spikes in December, its first and only wave, from 11 March8 to 10 May 2020, recorded only 393 positive cases of COVID-19. Over the same period, South Korea reported 3,361 cases, while Hong Kong reported 927.

By year-end 2020, it had still only recorded 817 cases of COVID-19 and just seven deaths, while Hong Kong had reached 9,050 cases and 153 deaths. South Korea brought up the rear of this trio with 64,979 and 1,007 respectively. However, Taiwan certainly saw a brief but uncharacteristic blip around June 2021 when new daily case declarations hovered around the 500 mark.

4.10 The pop-up hospitals

In reacting to the rapid increase of COVID-19-related hospital admissions, the world did seem better prepared to face the pandemic than it did in many other respects. Like other countries, in England the NHS freed up around 15,000 beds by cancelling elective (planned) operations. Another 15,000 were freed by discharging patients primarily into care homes, while a further 8,000 were purchased at cost from the private sector. However, social distancing necessitated extra space between beds thereby reducing the total number that could be accommodated across the hospitals.

Pop-up hospitals started appearing – sometimes as a reaction to an immediate demand for extra beds and intensive care capability, other times as a contingency measure.

The day after the Wuhan lockdown in China (refer to section 7.1), work started on constructing the Huoshenshan and Leishenshan Hospitals. With the names of the hospitals meaning Fire God Mountain (Huoshenshan) and Thunder God Mountain (Leishenshan), these two 25,000 square metre pop-up hospitals were constructed using prefabricated units. providing a combined capacity of 2,300 beds.

The project was completed in around 10 days, and was based on Xiaotangshan Hospital, which was constructed in Beijing to help manage the SARS virus in 2002-2003. The Xiaotangshan was in fact reopened during the COVID-19 crisis, although other pop-up hospitals were also planned.

Other countries activated their contingency plans, too. The UK quickly converted a number of existing buildings into what were referred to as ‘Nightingale Hospitals’, adding around 12,000 extra beds in England alone. This included a former railway terminus – ‘Manchester Central’. On two previous occasions, the UK had temporarily commandeered and converted operational railway stations (Kings Cross in London and Manchester Victoria) into triage centres to manage casualties following terrorist attacks.

In the US, the hospital ships, the USNS Mercy and Comfort, were deployed to Los Angeles and New York respectively, while field hospitals were erected, such as the one in Manhattan’s Central Park, to provide hospitals with overflow capacity.

The healthcare system in Italy was in serious trouble at the height of its first wave. The country turned to shipping containers converted into intensive care facilities to complement the country’s hospital capacity.

Although there are other examples from around the world, the last example I would like to mention is in the Netherlands. With the Eurovision Song Contest 2020 being cancelled, the Rotterdam Ahoy concert venue was converted into an emergency hospital to help in the battle against COVID-19.

There is one final fundamental point that must not be overlooked vis-à-vis pop-up hospital strategies. It is certainly a very positive step that some countries are able to react in this way. However, at the risk of stating the obvious, they must not forget they still need to find the trained resources to man these hospitals without leaving other parts of their health services dangerously exposed.

In some countries, it was not always possible to locate a ‘pop-up’ hospital close to existing health facilities. This often presented the challenge of finding sufficiently trained staff to operate them without leaving other areas of their respective health services exposed. However, as the pandemic ebbed and flowed, the need to keep the pop-up facilities permanently operational all but disappeared.

Nevertheless, the alarming proliferation of the Omicron variant towards the end of 2021 re-emphasised the need for ‘pop-up’ hospitals. In some countries, including the UK, purpose-built structures were erected in the grounds of existing hospitals. This made it easier to manage the extra demands that the pop-up facilities placed on trained staff.

4.11 Risk managers criticised

“I am constantly amazed by the number of executives who dismiss potential disasters as being too unlikely to consider, or who put off dealing with known risks because they have other things to worry about.”

Martin Caddick, Former Head of Resilience, PwC, UK (Clark, 2014, p 8)

As this chapter has established, the writing was clearly on the wall vis-à-vis the pandemic threat, supported by a plethora of multi-source, high-profile warnings. I find it inconceivable that so many organisations seemed utterly unprepared. It would also appear that some countries did not appear to believe in their own NRRs and the veracity of the pandemic threat.

Tracey Skinner, Director of Insurance and Risk Financing for the BT Group, was critical of risk managers and said:

“With hindsight, risk managers could have done a better job of identifying pandemics as a threat before Covid-19 hit.”

(Norris, 2020)

4.12 The final word on global preparedness

TIP, whose formation was explained in section 4.9, spent eight months reviewing evidence of the spread, actions and responses to the COVID-19 pandemic. It has produced a definitive account of what happened and why, and has analysed how a pandemic can be prevented from happening again.

In its 2021 report, “COVID-19: Make it the Last Pandemic – A Summary”, TIP observed that:

“Years of warnings of an inevitable pandemic threat were not acted on and there was inadequate funding and stress testing of preparedness, despite the increasing rate at which zoonotic diseases are emerging.”

(TIP, 2021)

It seems appropriate that the head of the WHO has the final word on just how ready the world was:

“None of this should come as a surprise. Over the years there have been many reports, reviews and recommendations all saying the same thing: – the world is not prepared for a pandemic.”

4 The number of cases, fatalities and mortality statistics quoted for SARS, MERS and COVID-19 were as of 31st December 2021.

5 Before the end of August 2021, UK fatalities had exceeded 131,000, more than any other European country and, at that time, globally exceeded only by the US, India, Brazil and Mexico.

6 https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/644968/UK_National_Risk_Register_2017.

7 https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/644968/UK_National_Risk_Register_2017.

8 10 March 2020 was the date the pandemic was declared by the WHO.