CHAPTER 5: IS IT TOO LATE TO WRITE A PANDEMIC PLAN?

With the world’s first COVID-19 vaccine having been approved by the UK in early December 2020, the more optimistic among us who believe that COVID-19 will soon be just a distant memory, might feel justified in asking this question. Now to remind you that I am not a clinician or a virologist, but in my humble opinion as a Fellow of the Institute of Strategic Risk Management, COVID-19 is not the severe pandemic that the world was expecting.

That might surprise you, but as I explained in section 4.5, the various NRRs I have had sight of have all flagged a severe influenza pandemic as their biggest concern. While the custodians of these NRRs may well choose to re-examine their assessment of emerging infectious diseases, such as coronaviruses, I see no reason why they would want to change their thinking regarding influenza pandemics. Also, keep in mind that with COVID-19, it could be several days after being infected that symptoms start to present, assuming the infected individual is not asymptomatic. Conversely, when the 1918-1919 Spanish influenza pandemic was raging, people could look a picture of health at breakfast time but be dead before dinner time.

“Are we entering the Century of Pandemics?” (Dr Jonathan Quick, 2018)

History has taught us that periodically we will be threatened by the onset of a severe influenza pandemic. Maybe it will be this year, perhaps next year or conceivably sometime in the next ten years. If you take a look at the UK NRR, which, to remind you, is in the public domain, you’ll see that the probability of a severe influenza pandemic occurring in the next five years is between 1-in-20 and 1-in-2. The truth is we may not know for sure when that will be until it is virtually breathing down our necks. Unfortunately, the bad news is that Mother Nature does not publish a useful timetable of forthcoming dangerous and disruptive events. As consolation, I should add that the WHO has created a global influenza surveillance response system. Even so, we also only need look at the COVID-19 proliferation timeline to see how fast the disease has spread. Yet, until the case count exploded in China, most of us had never heard of it. Moreover, China had recorded almost 45,000 cases with over 1,100 associated deaths before this novel coronavirus had even been given a name.

Now let us contemplate the plethora of unregulated organisations that had either never given pandemic planning a thought, or had opted to prepare only when they were warned that one was imminent. So, consider this:

• On 1 February 2020, there were around 14,500 known coronavirus global cases and 300 associated deaths.

• One month later, those numbers had increased to 88,000 and 3,000 respectively.

• Within two months, the count was 1,000,000 cases with 50,000 fatalities.

• After three months, the case count was up to 3,356,391 and fatalities had reached 244,917.

So, had your organisation been one of the “let’s wait and see what happens” brigade, or “we will create a plan when we know the threat of a pandemic is looming”, at what point would you have hit the panic button? Moreover, how long do you think it will take to actually develop a plan – it certainly is not an overnight task. Moreover, you will have no doubt found that many of the consumables that you were invariably going to need (e.g. PPE, hand sanitiser, cleaning products, etc.) were in very short supply.

Some organisations may argue that they have engaged with business continuity and have a validated BCP. That is clearly good news, but is that sufficient when you are facing a serious pandemic? Those organisations that are familiar with the BCI’s Good Practice Guidelines (GPG), will appreciate that:

“The business continuity plans are not intended to cover every eventuality as all incidents are different. The plans need to be flexible enough to be adapted to the specific incident that has occurred and the opportunities it may have created. However, in some circumstances, incident specific plans are appropriate to address a significant threat or risk, for example, a pandemic plan.”

(BCI, 2018, p 62)

I believe it is safe to assume that, in addition to a BCP, the GPG is recommending that organisations develop and maintain a contingency plan specifically for pandemics.

And here is some more bad news. SARS-CoV-2, to use its viral name, is the third potentially fatal coronavirus to have emerged since the turn of the millennium. That makes it three coronaviruses inside 17 years. If they keep coming at that rate, then we have at least one more novel coronavirus to look forward to before 2030.

To return to the question ‘Is it too late to write a pandemic plan?’, when considering the ever-present influenza threat plus emerging infectious diseases, the answer is most emphatically ‘NO’, it is not too late.

Other sources of information out there that can help organisations prepare to face a pandemic include the Arizona State University (ASU). It has published “A comprehensive survey on how companies are protecting their employees from COVID-19”. Using survey data collected from more than 1,000 companies across 29 countries, it reveals the stark challenges in navigating the pandemic (ASU, 2020). Supported by the Rockefeller Foundation, more recently ASU has also prepared a very useful resource entitled “Back to the Workplace: Are we there yet?” (ASU, 2021).

5.1 Did you have a pandemic plan in place?

5.1.1 Yes, we had prepared a pandemic plan

For those organisations that had a pandemic plan in place before COVID-19 arrived, you need to be asking yourselves some serious questions, such as:

• Did the plan work?

• What went well, what could have been done better and what went badly?

• What lessons did you learn?

• Did your organisation find itself facing any unexpected risks? In which case, are there any future mitigation actions or contingency activities you should consider?

• What incorrect assumptions did you make in originally preparing the plan?

• Did government legislation and regulations help or hinder your ability to conduct your business?

You may not know all the answers to any issues arising until after the pandemic is over. But there is no harm in making any changes to the plan that you realise are necessary.

5.1.2 No, we didn’t have a pandemic plan

The first thing to remember about a pandemic plan is that, like a BCP, one size does not fit all. For example, there is little point in using a plan that was perhaps developed for a financial institution if you are, say, a manufacturing outfit. That said, your pandemic plan should work in conjunction with your BCP.

In the prequel to this book, I devoted around 70 pages to how to go about writing a pandemic plan. In the following sub-sections, for your convenience, I have included an overview of some key points that you will need to consider while preparing your own plan. Please keep in mind that the shape of your plan will be very much influenced by whether your country considers your business to be essential or non-essential. In the latter case, in the event of a total lockdown, you are likely to be unable to operate from your premises until the restrictions are lifted.

While accountability must lie with senior management, where in your organisation should you position the responsibility for developing your pandemic plan? Ideally, this should be managed from the same area of the organisation that deals with your business continuity planning or within risk management. However, it would be wise to seek medical expertise to advise and provide independent validation of your plan. Your HR team can also expect to play a key role in the plan’s development.

5.1.2.1 First and foremost, your employees

a. Where possible and practical, if your staff can work from home (WFH), then this should be encouraged. You will need to ensure that staff are properly equipped and, if appropriate, they have an acceptable Internet bandwidth. Keep in regular contact with them either via online meetings or phone calls. Be aware of the potential for both mental health and well-being issues, plus musculoskeletal disorders resulting from long periods of using display equipment.

b. You should try and make allowances for those employees who are more vulnerable to the pandemic, perhaps because of underlying health issues.

c. Be prepared for staff absenteeism, which could be for any one of a number of reasons (e.g. sickness, childminding, sick parents needing care, transport issues, in isolation, fear, etc.)

d. Ensure staff know what to do if they develop any pandemic-related symptoms, whether they are at home or work. This will invariably be based upon in-country medical guidance. While an individual’s COVID-19 symptoms can deteriorate over a period of days, other illness can develop very quickly, such as influenza.

e. Develop a process for dealing with workers who may be taken ill at work, which minimises the threat of cross infection to other workers. Although it hasn’t been necessary with COVID-19 as the symptoms develop relatively slowly, in the event of an influenza outbreak, having a medical room available can be a useful means of helping to manage sickness at work. Ensure that procedures are in place to follow-up with cleaning any areas of the workplace potentially infected.

f. Allow sick staff sufficient time to recover from the pandemic, keeping in mind that some may suffer from an extended period of post-viral fatigue (e.g. long COVID – see section 3 etc.).9

g. Consider enlisting the service of trauma counsellors should staff be severely affected by the death of any colleagues. You may choose to extend this service to include the death of their loved ones, including close friends.

5.1.2.2 Making the workplace safe

Various governments have published guidelines about keeping both staff and customers safe in the workplace. In the event that you cannot locate any relevant documents for your own country, I have included a number of useful URLs on my website: www.bcm-consultancy.com/pandemicthreat.

There are several recognised ways in which your employees and customers can be infected by the virus in and around the workplace. This can include:

• Employees coming to work when they are presenting symptoms that can be for any one of a number of reasons (e.g. they will not be paid if they stay at home, a sense of loyalty – letting the team down, etc.). This type of situation needs to be addressed by your HR team before it becomes an issue in the workplace.

• When hands are not washed or washed adequately.

• Workers not observing coughing and sneezing etiquette, including not wearing face masks, especially when working indoors.

• Cross infection occurring in potentially high traffic areas, such as toilets, canteens, ingress and egress points.

• Inadequate cleaning regime in the workplace.

• Contravening social distancing regulations.

• Inadequate ventilation in the workplace.

• Insufficient supplies of PPE, handwash and hand sanitiser.

• Workers co-habiting and/or car sharing when travelling to and from work.

The following actions should be considered as part of your workplace safety plan:

a) Introduce a process that ensures employee’s and visitor’s temperatures are taken regularly and, if required, log the results. Forehead thermometers are ideal for this, although there are more sophisticated alternatives that are less intrusive, such as those deployed in airports. Remember that whoever is responsible for monitoring temperatures should also record their own, too.

b) Educate staff in handwashing plus coughing and sneezing protocols. Prominently display posters around the workplace to act as constant reminders. Where one does not already exist, foster a culture of wearing face masks.

c) Ensure that ample supplies of PPE, especially face masks and hand sanitisers are available. Consider allocating staff with their own bottles of hand sanitiser. Do not wait for a pandemic to be declared before ordering supplies – they ran out when the comparatively minor 2015 MERS outbreak occurred in South Korea. When COVID-19 arrived, the global demand quickly outstripped the supply.

d) Perform a risk assessment with the primary objective of identifying:

i. Areas where people tend to congregate;

ii. Bottlenecks, especially where social distancing might be difficult to maintain;

iii. Surfaces that are likely to be touched repeatedly; and

iv. Indoor areas with poor ventilation.

e) Frequent cleaning of the workplace is essential, especially infection traps, such as elevator buttons, handrails, door access keypads, door handles, telephones, etc. This list could be extensive, and is also likely to vary from organisation to organisation. Special attention should be paid to cleansing any high-traffic areas identified by your risk assessment.

f) In the event that workers or visitors are taken ill on your premises, ensure that procedures are in place to follow up with cleaning those areas of the workplace potentially infected.

g) Prohibit cultural greetings that involve any form of physical contact.

h) Discourage face-to-face meetings if possible and encourage the use of online conference platforms. even if it is two or three people who work in adjacent offices. Keep in mind that staff may need training in the use of your chosen platform.

i) Travel, especially internationally, may become difficult if not impossible. Unessential travel should be avoided.

j) If staff cannot WFH, ensure your plan allows for accommodating all social distancing regulations.10

k) Consideration may need to be given to workplace ventilation, especially if windows cannot be opened.

l) Engage in dialogue with those workers who cohabit and/or travel to work together. Determine how to reduce the risk of them being vulnerable to infection and/or instrumental in the virus spreading.

m) Put in place one-way systems to reduce potential congestion and, if possible, designate staircases going up and others going down. Ideally nominate ingress/egress as either just an entrance or an exit from your premises.

n) While it may not be easy, it is also worth discouraging gossip in the workplace, especially if it specifically references pandemic conspiracy theories. The proliferation of misinformation could serve to undermine your efforts to keep the workplace safe.

5.1.2.3 Communications

Whenever you are faced with a crisis, your ability to communicate effectively can make the difference between a successful outcome or a major catastrophe. Having a well-rehearsed communication plan in place is an essential part of business survival, regardless of the nature of the crisis you are facing. Just to be clear, this communication is not specifically for a pandemic, it should be for any type of crisis that comes your way.

So, what needs to be in your plan?

Let’s start with the basics, how are you going to mobilise your crisis management team (CMT) and any other supporting team you may need (e.g. business continuity, IT disaster recovery, emergency preparedness, etc.). Crises can happen at any time and for those organisations that still enjoy the luxury of working from 9 am to 5 pm, Monday to Friday, then statistically a crisis is more likely to occur outside of your normal working hours.

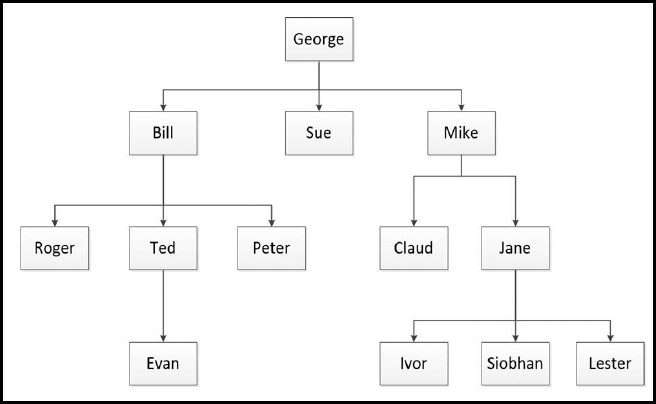

Figure 11: Telephone message cascade approach

Some, usually small- to medium-size organisations, may opt to use the telephone message cascade approach. In the preceding illustration, George calls Bill, Sue and Mike. Bill then calls Roger, Ted and Peter, while Mike calls Claud and Jane, etc. But the more links there are in the chain, the greater the chance of the chain breaking.

In one crisis rehearsal exercise case I researched, it was acted out over a weekend. The scenario was a plane crash at an airport and the local hospital was involved. It was an unannounced exercise, and they used the message cascade approach, but the person responsible for alerting the hospital catering manager, failed to make the call. The catering team were expected to keep the emergency workers fed and watered over the weekend. But, owing to the message cascade failure, no field kitchen facilities were deployed and there were no refreshments available for the entire weekend.

What is becoming more popular are mass notification systems which, in addition to mobilising your teams, can be used for emergency warnings, too (e.g. active shooter, tsunami threat, wildfires, chemical spills, etc.). The better examples on the market certainly remove the risk of a cascade call chain breaking.

Your communications will also need to take account of your stakeholders, and an obvious pre-requisite is actually knowing who your stakeholders are. Surprisingly, not everyone does, but they may be:

• Referred to as an ‘interested party’;

• A critical component in the successful resolution of a crisis; and

• An individual person, a group or an organisation.

You must know WHO you will need to communicate with, HOW you are going to communicate with them and WHAT you are going to tell them. Also, keep in mind that communication is a two-way thing, so you must be set up to monitor and react to inbound messages, too.

So, let’s think about the WHO. For example, your stakeholders could include the following:

• Authorities/government

• Competitors

• Customers and suppliers

• Emergency contacts

• Shareholders

• Employees

• Local communities

• Media

• Regulators/legislators

• Financiers

There may well be others that you will have to factor into your plan accordingly. On occasions, you may need to consider the order in which you communicate with your stakeholders. This begs questions, such as: ‘Is there anyone we should be telling first?’

Next, HOW are you going to communicate with your stakeholders? You will need to define your communication channels and decide on the most appropriate for each stakeholder group, such as:

• Mass notification systems

• Internet/website

• Telephone/SMS texting/fax

• Radio/television

• Local/national newspapers

• Social media

• Media advertisements

• Trade journals

Now here is the thing. Communication channels can be compromised by the very crisis you are trying to manage. Consequently, I would strongly recommend that you include some contingency measures in your plan that would enable continuity of communications by using alternative channels.

It is also worth remembering that when a crisis starts, people will expect answers and quickly. For example:

• The 2002-2003 SARS outbreak happened while social media was very much in its infancy. Over the three days, 8-10 February 2003, the SMS text message: ‘There is a fatal flu in Guangzhou’ was sent 126 million times just from mobile phones in the city of Guangzhou alone (Brahmbhatt & Dutta, 2008).

• The week following the 2007 bombing, Glasgow Airport website received 130,000 visits compared to 6,000 the previous week. (Crichton, 2007, pp 18-23)

• When the 2009-2011 Toyota product recall crisis reached its peak, circa 14,000 daily inbound phone queries were received in the UK alone. (Duncan, 2014, p. 252)

• After the 2015 Paris terrorist attacks, approximately 10.7 million tweets were posted in a 24-hour period. Twitter is just one of many social media platforms. Much of this Paris-focused information was incorrect or arguably ‘economical with the truth’. (Whitten, 2015)

So, WHAT are we going to communicate?

For each threat scenario that has been included within the crisis management scope, it should be possible to construct a set of communication templates to speed up the process of responding. These templates should be subject to a programme of continual improvement, as more experience is gained by the organisation.

Keep in mind that an organisation’s chief executive officer is not always the best person to stand up in front of the media.

5.1.2.4 Supply chain management

Examine your upstream supply chain, especially if it has more of global rather than local dependency and reflect on just how vulnerable to a pandemic it could be. When China went into lockdown, many organisations found products that they depended upon were no longer easily obtainable. This very much impacted global health services and their urgent need for PPE.

A friend needing to ship a small package from Australia to the US was informed that the transit time (normally just a few days) would now take several weeks. Oh, and the price had gone up 10-fold, making the shipment more expensive than the value of the product.

Those organisations operating a just-in-time (JIT) supply chain model could find they are especially vulnerable. Many passenger airlines effectively closed down, which meant their cargo holds were no longer available for shipping products quickly around the world. You should also consider your downstream supply chain – your customers. If your operation is interrupted, maybe because of a lockdown, how will you inform your customers that you are back in business? Or, if you are able to continue operations during a lockdown, how will you tell them ‘we are still here’, always assuming of course that your customers are still in business, too.

One example I rather liked was Amazon originally created a ‘COVID-19 Information’ page on its website. This kept customers up to date about how Amazon was dealing with the pandemic and, more importantly, was reassuring them that it was still open for business.

And a final thought. Do your suppliers have BCPs and pandemic plans in place and are they prepared to share them with your organisation? In the interest of being reassured, there is no harm in asking – some of your customers may ask you the same question.

5.1.2.5 Resources to help you create your plan

If you don’t already have a copy of the prequel to this book, just to remind you that it has around 70 pages devoted to writing a pandemic plan.

You will also find a number of useful pandemic-related resources, including sample plans, case studies, videos and useful links on my website:

www.bcm-consultancy.com/pandemicthreat.

9 Some countries are not very generous with paid sick leave allowance. Staff may be tempted to return to work while they are still infectious because they cannot afford to remain at home if they are not being paid. I know of at least one country that permits only two weeks paid sick leave even when an extended period of hospitalisation is necessary.

10 Social distancing recommendations have not been applied consistently globally, with some countries opting for one metre while others have chosen two. Your social distancing plans may need to be flexible, especially as recommended distance may be increased or decreased as more is learned about the virus. There have been incidents where it has been revealed that social distancing has not been adequately observed (e.g. food processing plants, etc.) but workers have been reluctant whistleblowers for fear of losing their jobs.