CHAPTER 13: IMPACT ON EDUCATION

Should education be classified as a business or an industry? There are arguments both for and against. Whatever you own personal opinion happens to be, there are certainly lessons (both positive and negative) that the more traditional business sectors can learn from the educational response to the pandemic. This chapter considers the effects of these lockdown restrictions and responses, by looking at educational examples primarily from the UK and China.

Many universities, schools, kindergartens and even commercial training organisations around the world have been closed down to restrict the spread of COVID-19. The formal classroom teaching approach was one of the early victims of the pandemic. In the UK, some schools remained open for the children of essential workers (e.g. emergency services, health and care workers, etc.) who would not be able provide home schooling support.

There have been many encouraging accounts of children being effectively home schooled, although this has invariably depended upon the appropriate technology being available to support this. As previously mentioned, supply chain issues for tablets and laptops quickly manifested themselves as the business world also scrambled to procure equipment to support their staff WFH.

Conversely, disturbing reports have also surfaced of children, often in their teen years, locking themselves away in their bedrooms for hours on end much to the consternation of their parents. Concern grows for the longer term psychological impact that this could cause.

“In 1665, following an outbreak of the bubonic plague in England, Cambridge University closed its doors, forcing Newton to return home to Woolsthorpe Manor. While sitting in the garden there one day, he saw an apple fall from a tree, providing him with the inspiration to eventually formulate his law of universal gravitation”.

(Nix, 2020)

One must wonder whether anyone forced to work at home during the pandemic, may, like Isaac Newton, also experience an ‘Annus Mirabilis’.

What is unsurprisingly apparent is that schools and universities are just as vulnerable to both staff and pupils being infected with COVID-19 as any other sector of the community. In the UK, schools reopened at the end of August 2020. However, within a just few days, incidents of infected staff and pupils were being reported. On one day alone in Greater Manchester, COVID cases were confirmed at more than 40 schools, necessitating children being sent home (Gill, 2020).

Concern had also been expressed in the UK regarding universities reopening their doors again in September. There had already been incidents reported vis-à-vis students blatantly ignoring social gathering rules and partying. In response, some universities issued tough warnings that any miscreants caught engaging in such activities faced expulsion. Even so, universities throughout the UK have had to insist that students testing positive, plus those who are known to have been exposed to COVID-19, must isolate. The consequence has been thousands of students isolated in halls of residence and shared accommodation.

Although the vast majority of students who almost inevitably become infected with COVID-19 may well be asymptomatic, the concern surrounds the potential impact when they return home, taking the infection into the wider community. US universities reopened two months earlier, from which there were certainly lessons to have been learned, although they seem to have been largely ignored. Writing in The BMJ, Gavin Yarney, Professor of Global Health and Public Policy and Rochelle Walensky, Chief of Division of Infectious Diseases observed:

“The national reopening experiment already looks to have been a disaster.”

(Yamey & Walensky, 2020)

Major campus outbreaks have resulted in universities being shut down. The University of North Carolina (UNC) is an example where, from a 30,000 student population, 130 new student cases plus five staff were detected in the first week. This prompted UNC to switch to online classes. Across the country, at least 26,000 cases have been reported in 750 colleges and universities, an average of 35 cases per institution.

Yamey and Walensky identify three specific lessons that can be taken from the US experience:

1. Curbing community transmission of COVID before reopening. They cite the positive example of Taiwan in reopening its universities only after achieving virtual elimination of community transmission.

2. The value of quarantining students before arrival.

3. Transmission of the infection between asymptomatic students can be rapid. Congregate situations, especially residential halls and shared off-campus accommodation, can create high-risk locations.

Any testing programmes should include both students and staff, and every effort should be made to shield the older and more vulnerable, particular those with underlying health conditions.

13.1 The Royal Hospital School, Ipswich, UK

The RHS is an independent co-educational boarding and day school for 11-18 year olds. It provides an outstanding, full and broad education, fit for the modern world, and enriched by a unique naval heritage. Having spent five years there myself, I can tell you it is an amazing place.

Founded in 1712 in Greenwich, London, it moved to its spectacular site, set in 200 acres of Suffolk countryside overlooking the River Stour, in 1933. The school has continued to develop its stunning purpose-built site and has grown in size and reputation to become one of the UK’s leading independent schools (RHS, 2020).

From a very early stage of the pandemic, RHS had an evolving set of risk assessments and plans. But, as in any crisis, plans need to be flexible, although they were based upon its guiding three principles of:

1. Protecting the health and well-being of pupils, staff and the wider community by minimising any risk of transmitting the virus.

2. Prioritising the learning and academic progress of pupils, regardless of whether they can be physically in school.

3. Maintaining effective communications with both the pupils and staff community.

Like every other school in the UK, RHS went into lockdown on 20 March 2020. But, unlike so many other schools, and in fact many businesses too, the following Monday, lessons seamlessly recommenced, offering its entire academic timetable, albeit online (see section 8.2 – Teaching children by remote learning). Boarders were cared for at the school until it was safe to return home.

When the school reopened as the UK lockdown was relaxed, over 720 pupils returned. With 400 boarders included in the mix, RHS has adopted the Boarding School’s Association COVID Safe Charter. All pupils and staff are constantly reminded to observe social distancing guidelines.

“There is genuine recognition that to be back in class is a positive step but as both a parent and a headteacher, there is also a concern about what lies ahead. Further disruption to our children’s education could be much harder a second time around. The initial novelty that was associated with a national lockdown may be replaced with a sense of frustration and helplessness for pupils who are already concerned about the implications for their future in the workplace.”

(Simon Lockyer, Headmaster, RHS, September 2020)

As it proved necessary to lock down again in January 2021, the school immediately reverted to live, online teaching.

“After the COVID-19 forced closure on Friday 20th March, with iPads the school had provided pupils, and using Microsoft Teams, 108 teachers began teaching 750 pupils, in 38 countries, 28 subjects the following Monday. By the time the school reopened, over 22,000 online lessons had been delivered.”

(Independent School Parent, 2020)

“The moment the schools closed RHS were providing a full online timetable for all of their pupils. We were so impressed that our children didn’t miss a single lesson and still had such regular meetings with their tutors. Our kids also loved all the fun sports challenges to help them stay fit and have some fun! Thank you RHS for supporting our children through such a tough time.”

(RHS parent)

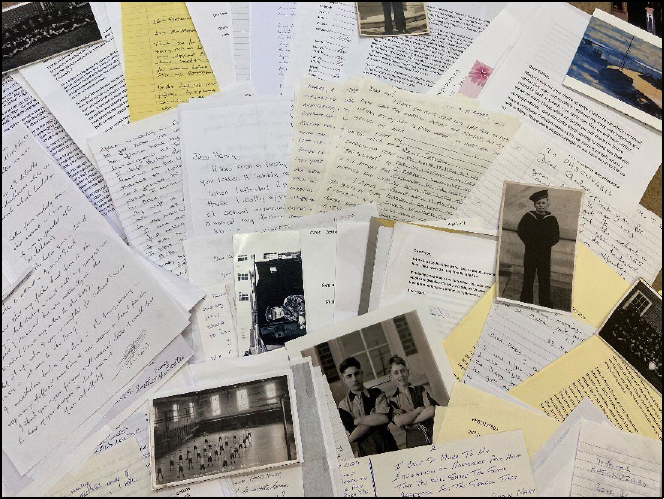

Many people around the world, especially the elderly, may well have felt isolated and lonely whenever they found themselves in lockdown. As part of a joint initiative run by the RHS Compass Programme, which teaches citizenship, and the school’s alumni association, pupils were encouraged to write to around 800 of the older alumni to help combat loneliness, (Sandalls, 2020).

Some pupils went even further. Three Year 11 RHS students also wrote letters on behalf of the Rural Coffee Caravan which were delivered to those isolated, elderly, or vulnerable during the pandemic. Their efforts did not go unnoticed. They were among a number of teenagers recognised by the inaugural Suffolk Hope awards whose judges included representatives from Suffolk police, Suffolk County Council and Suffolk Hate Crime Network (Earth, 2021).

Figure 36: Just a few of the letters written by RHS pupils

Back at school, pupils have been expected to use alcohol-based hand sanitising gel whenever they are entering classrooms. Face mask wearing, plus handwashing etiquette is also rigorously enforced, especially after using the toilet plus before and after meals. Sanitising wipes are provided for pupils to clean their desks before and after every lesson.

Day pupils presenting any COVID-19 type symptoms (see section 4.1.3) should not be sent to school on that day. Pupils presenting any COVID-19 like symptoms while at school will be escorted to the health centre. Day pupils will remain at the centre while awaiting collection by their parents/guardians.

Such was the effectiveness of the measures implemented by the RHS, by the end of term, December 2020, the school had only one case (a day pupil) of COVID-19 reported among staff or pupils.

One other point certainly worthy of mention is, wanting to help out with the initial PPE shortage, the school’s Design and Technology team started making protective face masks for the NHS in the county of Suffolk, where the school is located.

13.2 Cottage Grove School, Portsmouth, UK

The school is based in an area of high deprivation, and has approximately 450 pupils. It is a two-form entry primary school with a nursery attached, with ages ranging from 4-11 years. There are 85 staff, of which 28 are teachers, made up of a mix of part time and full time.

Between them, the children can speak around 38 different languages, with only 45% having English as their first language. The other main language groups include Bengali, Kurdish, Farsi, Arabic and Romanian. A number of the parents would normally be studying for doctorates or masters’ degrees at the University of Portsmouth, so consequently many of the children are transient.

A large proportion of the local children come from high-rise and low-rise council owned apartments, local authority temporary lodging and Salvation Army supported housing. Occasionally, children will come from local woman’s refuge centres. When a child first arrives, staff can never be sure exactly how long they will be attending the school.

Headteacher, Polly Honeychurch, who has been at the school for over 20 years, takes up the story:

“Leading up to the pandemic

In early 2020, the media was full of the images of the coronavirus outbreak in Wuhan, plus the Diamond Princess quarantined in Japan. However, we didn’t feel threatened in anyway as that was on the other side of the planet. Then, before anything came through official channels, I was warned of the impending pandemic via the book club I belong to. A fellow member’s husband is a consultant at Queen Alexander Hospital, Portsmouth, and he too had been watching the developments in China and Japan. The friend remarked that she had never seen her husband so scared. He simply said, “that is coming here!”

Figure 37: Cottage Grove Primary

Staying safe in school

In line with the first UK national lockdown directives, we closed the school except for vulnerable children and the children of key workers. This left us with between 40 and 50 children still attending school. Where practical, I instructed staff to work from home but there are some jobs which you can only do on site, such as teaching those children in attendance, however few, cleaning and lunchtime supervision.

What was good to see was the children adapted very quickly to the changes that we had to introduce. More often than not it was the staff that needed reminding, especially about social distancing. I found it necessary to reorganise the staff room by reducing the number of easy chairs from thirty to six and reducing chairs at the staffroom table. Disinfectant spray was left on the table for staff to clean up after they had finished.

While staff were trying to adapt to the cultural changes imposed making references to the ‘new norm’, for the children joining us in the reception year, to them, this was the norm. Moreover, the children often proved to be far more resilient than adults.

Morning and afternoon school arrivals and departures were staggered, and the year groups were instructed to use separate entry and exit points. However, some parents did prove problematic especially those who would not observe social distancing protocols or wear masks when delivering or collecting their children. I did have parents inform me that they were reluctant to come to the school as they felt threatened by this inconsiderate and anti-social behaviour. Moreover, while parents had previously always been welcomed into the school, we had to insist that they remained outside the parameter and, if they did need to speak to someone, they would have to make an appointment.

Children were split up into year group bubbles. Movement around the school was restricted and we introduced a one-way system. Girls’ and boys’ toilets were reallocated to year groups to prevent any potential for cross-over infection between the groups. A staggered arrival for lunch with each year group bubble being allocated their own tables. Instead of queuing at the kitchen hatch for their lunch, it was brought to them at their tables. When they had finished, their tables and chairs were cleaned in preparation for the next group.

Prior to the pandemic, assemblies were held daily, this is currently reduced to one assembly each week. This was an online session which children and staff could sign into whether they were in school or at home. We have been using the Google Meet platform, but I quickly learned of its limitations as I managed to crash it when over one hundred tried to logon simultaneously. We now have a Zoom account which allows up to 500 users. It has been very encouraging to see a good level of engagement from those at home.

Between the initial lockdown in March and the end of November 2020, we had just two cases of COVID-19 in school. One pupil and one staff member. However, in December 2020 alone, the case count shot up to 20, which included 10% of all staff.

A number of staff have also been ‘pinged’ by track and trace and they have self-isolated for the statutory ten days. But staff never knew why they had been pinged and none presented any symptoms. They were either never pinged at all or were pinged on multiple occasions, and some appeared to lose confidence in the system especially when they never presented any symptoms.

In January 2021, self-testing kits arrived at school for use by staff and these were the type sent out for use at home rather than testing centres. The only training I had received was in the form of two one-hour webinars and I then had to instruct staff how to self-test.

Communications

Lines of communications have not always been reliable or coherent. I often learned of policy changes via the media or the daily briefings from Downing Street rather than directly from the Department for Education (DfE). That said, the DfE took to issuing communications often via lengthy documents one day and then continued to regularly reissue the documents with minor changes. But they would not just indicate what had changed, making it necessary to re-read the entire document, thereby causing unnecessary information overload. This wasted valuable time, which could have been avoided.

One mixed message that caused confusion was that politicians were initially making statements that school environments were safe. Then immediately before the January 2021 lockdown came, the contradiction when we were told that schools were vectors of transmission. Which is it?

We have also been receiving confusing and often conflicting messages from the DfE regarding face masks and social distancing.

Online teaching

We have learnt so much since the initial lockdown in March regarding how to go about online learning for children. In hindsight, what the school could offer children at the outset was awful compared to what we are doing now.

During that initial lockdown, it gave the school the chance to try out some things and I gave teachers the opportunity to deliver in a way that they wanted to. By September, we had reviewed what everyone had done and how successful or not that had been.

The Key Stage 2 children, that’s the 7-11 year olds, use Google Classroom. Every child has their own Google email address which they would use when they logged-in while in the classroom. At home they would go through the same process.

From September 2020, they were able to try using Google Classroom in the school, which was good practice for studying at home. Every day in Google Classroom, work is already set for them and it is easy for them to contact their teacher. It is also easy for teachers to email the whole class at a time or individuals.

Ideally, classes would engage in regular Google Meet sessions. However, the school needed to be mindful that siblings may be sharing a device so they cannot guarantee that all children in a class will be logged on simultaneously.

There are still children who do not have access to a device. Initially, the school was allocated 64 computers from the government scheme and we have since given out 90 devices to families so far. Other families are on a waiting list, although we have no devices physically in school to give them at present. The government is promising more equipment and the school is awaiting the green light to order them as we will be instructed what we can order and when. I do also appreciate that there have been supply chain issues as many businesses have been scrambling to procure laptops and tablets to support their own home workers Key Stage 1 children, aged from 5 to 7 years, are using a platform called Seesaw. This is easier for them than Google Classroom, especially as it can be used on a phone or tablet making it a lot more accessible.

Some families do not have internet access and the school has obtained SIM cards, each preloaded with 10 Gigabytes of data. When they have used the allocation, they can go back to the school for a replacement card. Routers for families have also been ordered but they have not yet arrived.

There is a big digital divide between families and I consider these children with no home broadband or devices to be vulnerable children. These are the children that would typically be put in school during lockdowns alongside essential worker’s children.

While there are still some families that will not engage with online learning, an estimated 70% are taking home schooling seriously. Occasionally, the issue has been the result of parents not knowing what to do, and we have endeavoured to plug the gap by providing tutorials for them. But, on a positive note, there are two families back in Dubai and one in Romania still accessing online lessons.

At the centre of the community

The austerity cuts experienced in the UK since the financial crisis have resulted in many local services disappearing, leaving schools as the only constant. Consequently, the only place people can go to is the school as, in many cases, that is all that is left. Therefore, parents have been turning to the school for a whole range of things such as:

• Technical support to assist with home schooling;

• Emotional support;

• Physical support; and

It seems that whatever problem the local community has, the answer will be invariably found at the school.

Communicating with some parents can be challenging when messages can be lost in translation. Explaining what isolation means has sometimes proved difficult. One parent had nine children at the school from two separate families. However, despite counselling to the contrary from the school, he would spend time with both groups. He was also known to have travelled back and forward to Bolton in the north west of the UK, an area that has been flagged for its almost uninterrupted high infection rate. He and his children were all ultimately infected by COVID-19.

A few silver linings …

Strange as it might seem, there have actually been some benefits from how we have reacted to the pandemic. Firstly, I have noticed a big improvement in the children’s behaviour, something that is always appreciated by teachers.

It had always been my intent to empower the management team to make decisions on behalf of the school, thereby delegating some responsibilities. The pandemic rather forced my hand in terms of expediting the implementation. Staff were then encouraged to take any concerns or issues to the management team who were empowered to address them accordingly. There have been occasions when staff have not got the resolution they wanted, and some have subsequently come to me to appeal the decision. However, even if I didn’t happen to agree with the ruling handed down, I was not prepared to undermine the team’s authority.

I have also noted the positive effect that lunchtime table services have had on the children. I have decided that after the pandemic is over, we will continue with the practice as it is a much nicer experience for them than the way it was done before.

Finally, limiting the contact between children in the school has worked really well. Despite being in the middle of a pandemic, there has been very little evidence of colds and flu.

In conclusion

Since the pandemic started, in the interest of health and safety, we have found ourselves continually having to refine the way things have been done. I have learnt not to take things at face value and never to judge a book by its cover. For example, there have been some people who I have previously underrated and yet they have stepped up and gone above and beyond. Conversely, there have been others that I thought were totally dependable that just could not cope.

It is also important to know what you can control and what you cannot, such as limiting the number of children I have in school. I had made that decision to restrict numbers even before the instruction to close in early January had been sent out by the DfE.

Finally, I recognise that my job has changed beyond all recognition over the last year. On reflection, it makes me wonder whether this much changed role is the ‘new norm’ for head teachers everywhere.”

13.3 Hangzhou Primary Schools, China

With a population of over 10 million, the city of Hangzhou is located in the Chinese province of Zhejiang, some 110 miles (180 kms) south-west of Shanghai. The city’s schools were closed for the Chinese New Year holiday on 26 January 2020, three days after the lockdown had been imposed in Wuhan, approximately 470 miles (750 kms) to the west of Hangzhou. However, like other schools across China, they did not reopen when planned on 8 February 2020, as the COVID-19 lockdown measures had been extended across the country.

While schools were still physically closed, online learning for students started on 25 February 2020 using DingTalk, an Alibaba Group product, which is described as an enterprise communication and collaboration platform.

Finally, Hangzhou schools started reopening between 13 and 19 April for staff to be trained in the new COVID-19 regulations. The students had a staggered return over the following week.

The new regulations were strictly enforced as described below:

Campus entry and exit

1. Prior arrival all students and staff must have completed the education board administered health-check survey.

2. All staff and students must be temperature checked upon arrival.

3. Social distancing – spots circa one metre apart placed on the floor for those waiting to enter.

4. Student entry staggered with the oldest students arriving first and then each grade arrives in ten-minute intervals.

5. Staggered exit with grade 1 exiting first and then every ten minutes another grade departs.

6. Health staff present at entry to help anyone with a fever or who are presenting other symptoms.

1. No groupwork or shared desks.

2. Staff and students required to wear masks at all times (this was in place for around two weeks).

3. Each classroom has a designated entrance and exit.

4. Anyone entering a classroom must use alcohol gel to wash hands prior to each entry.

5. Initially, the use of air-conditioning was not permitted. However, after three weeks, as the temperature rose, the school had the system disinfected and its use was again allowed.

6. All student and staff are temperature checked twice a day and the results recorded and provided to the school administration and education board.

Dining

1. All students eat in their own classrooms and bring their own sterilised dishes and utensils.

2. For subject teachers who are not homeroom teachers, the dining hall is open, but they can only eat in socially distanced and dedicated spots.

General

1. All classrooms and offices are provided with alcohol gel.

2. All staff and students are required to wear masks.

3. Staff are allocated with one mask every day.

4. Interclass events are prohibited during April, May and June.

5. No contact PE classes or team sports are allowed.

6. Classes receive designated slots for outside play (implemented after mid-May) so each class can use a designated outside space once every two days. (Each block has eight classes and two designated spaces.)

In case of staff or students presenting symptoms

1. If a member of staff or a student has a high temperature and/or other symptoms, they are assessed on site (for the purpose of deciding how strictly to apply classroom quarantine measures) before being sent to hospital.

2. Any classroom in which they have taught in is quarantined until the results of COVID-19 testing are known.

3. In the case of fever, the person in question cannot return to the school until they have been fever free for 48 hours (provided they tested clear of the virus). This regulation was in effect until around the start of June.

13.4 English Language Schools face a bleak future

While countries around the world struggle to keep their education systems running or to restart them as quickly as possible, destinations that specialise in offering English as a Foreign Language are facing lean times.

It is estimated that in 2019 in the Republic of Malta (pop: 493,559), around 14% of the country’s GDP came from tourism. Students who travelled to Malta for English Language tuition accounted for just over half of the tourism figures. But, during July 2020, only 1,800 of the expected 18,000 weekly student intake actually travelled to Malta. Consequently, the 1,400 English language teachers were feeling very exposed. Deloitte estimates that even with a best case government rescue package, at least half would still lose their jobs (Arena, 2020).

13.5 Home schooling

With schools closing around the world, many countries are promoting ‘home schooling’. There are those schools that can offer their students online support, as in the example of the Hangzhou World Foreign Language school (see section 13.3).

I do feel it must be challenging for many parents expected to take on the role of ‘teacher’, particularly if they are WFH themselves and they have their own work objectives to meet. When all is said and done, to become a teacher you usually need to undertake several years of training – something that most parents will not have done. It is also possible that children may know more about some academic subjects than their parents.

Even though my sons’ schooling days are well behind me, I have tried to put myself in the position of a parent expected to home school their own children. I have a master’s degree, I occasionally lecture in universities and I run commercial training courses. Yet, when I look at the school curriculum across the various age groups, I believe that in most subjects I would have most definitely struggled.

Home schooling can also rely upon technical resources, such as laptops or tablets, and for some families this can be an expense too far, especially if there are several children at home all competing for the same resources. Maybe even the same resources that parents need for home working.

While some schools have been able to provide ‘online’ lessons for their students, in the UK, the BBC had previously set up what they called BBC Bitesize, which certainly proved its worth during the pandemic. This provides daily education options for children from three years old up to the post-16-year-old age group. It also provides tips for parents in supporting their children’s home-based learning.

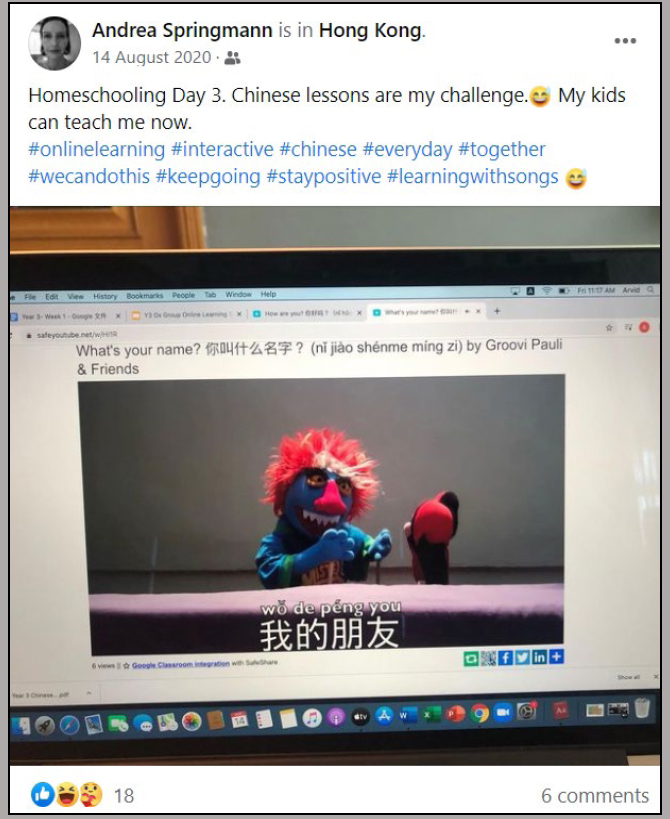

German national Andrea Springmann lives in Hong Kong with her husband and two children. Like many parents, she has endeavoured to home school her children which includes Chinese language lessons. As she reported on her Facebook page, her children are now more proficient at Mandarin than she is.

As for online lessons, these can be pre-recorded lessons or live, interactive sessions. One English as a Foreign Language teacher I know was expected to go down the pre-recorded route, while another had to be available for live tuition. Both had returned to the UK when the pandemic started, and while it may have seemed convenient to be able run online English lessons from the comfort of your own home, time zone differences meant that one teacher, had to start work at 2.00 am.

13.6 Traditional university

Students completing their university studies in the 2019-2020 academic year would not have anticipated the disruption that was about to be caused by the pandemic in their final few weeks. Along with schools, universities were closed as countries went into lockdown. In the UK, this happened just two to three weeks before the Easter holiday break.

Universities, along with other institutions in the UK, are finding it financially very difficult during the COVID-19 crisis. Approximately 2.38 million students attended in the academic year 2018-2019. The Institute of Fiscal Studies [IFS] states:

“The total size of the university sector’s losses is highly uncertain: we estimate that long-run losses could come in anywhere between £3 billion and £19 billion, or between 7.5% and nearly half of the sector’s overall income in one year.”

(Drayton & Waltmann, 2020)

The IFS also estimates that “The biggest losses will likely stem from falls in international student enrolments (between £1.4 billion and £4.3 billion, with a central estimate of £2.8 billion”. So, around 33% of expected income would normally come from 25% of students. This is seriously significant for universities and higher education institutes.

In a recent London Economics report it identified that:

Combining the impact of the economic downturn with the expected deferral rate due to the uncertainty caused by the pandemic, compared to 2018-219 first year enrolments, approximately 232,000 students will no longer enrol in higher education in 2020-221. Equivalent to a 24% decline compared to the baseline (2018-219) cohort, this will result in heavy economic fallout. With so many of the current universities being financially vulnerable, the threat of bankruptcy for some draws nearer unless support funding from other sources materialises. (Halterbeck, et al., 2020, p 15).

The UK government has since indicated funding is available on application. Education Secretary, Gavin Williamson, sought to reassure the sector when he announced:

“We understand the challenges universities are facing, which is why we have already provided a range of support to ease financial pressures.”

(Department for Education, 2020)

The government has indicated that as a condition for taking part in the scheme, universities will be required to make changes that meet wider government objectives, depending on the individual provider’s circumstances. Among these are delivery of high-quality courses with strong graduate outcomes, which is already a prerogative. However, they do not wish the focus on resources at the front line to be at the expense of reduced administrative costs. The three main objectives that the government restructuring initiative requires are:

1. Protect the welfare of current students.

2. Supporting the role higher education providers play in regional and local economies through the provision of high-quality courses aligned with economic and societal need.

3. Preserving the sector’s internationally outstanding science base (noting specific support is being made available for research activities).

Consideration will also be given to the ‘impact groups’ of students, teaching provision, local economy and communities, along with research knowledge and exchange. These requirements have been identified and contained within the document for prospective funding application.

The New Statesmen (2020) outlines that universities have already responded to a freeze on hiring new staff, cuts on temporary teaching posts and graduate student teaching jobs, along with restructuring and redundancies being part of the required objectives. They also state that thousands of jobs are already at risk. Worrying announcements have already been made at prestigious universities, including Oxford, Liverpool, York, Birmingham, Manchester, Nottingham, Glasgow, King’s College London and Durham, among others.

The unions have already pressurised for redundancies to be limited, with threats of strikes if the voluntary route is not followed first. This academic year has been a difficult one for staff, with issues of pay and pensions coming before the pandemic requirements were established. The next few years will be lean ones especially until a vaccine for COVID-19 is widely available to ensure that overseas students return in the numbers managed previously. Education has been completely turned around, and the future at this moment, until other areas of the economy are resolved, is looking very challenging.

Have universities become a concentration of risk?

Early September 2020, the University of South Carolina reported more than 1,000 of its 35,000 students had tested positive for COVID-19. Students have been urged to remain vigilant regarding social distancing, hand hygiene and mask wearing, while avoiding unnecessary social activities. Similar conditions have been reported by other universities.

13.7 Commercial training

I have been running a variety of training courses for over 20 years, primarily for commercial clients, and occasionally as a visiting university lecturer. During that time, while I have delivered programme management and project management, my preference is most definitely for business continuity, ICT disaster recovery and crisis management. It will probably come as no surprise to you that, more recently, I have added pandemic preparedness training to my repertoire. What is more, I can often dip into my various publications and pull out a relevant case study or two.

But, I do like working in a classroom with the students. To see the whites of their eyes, read their body language, and try and keep them awake during the ‘graveyard shift’, which tends to come immediately after lunch. And all this time I am pacing up and down the room while endeavouring to find appropriate words of wisdom to shower on the students. Judging by the positive consistency of the feedback I have received, the students largely appreciate my style of delivery.

Then came the pandemic. No one was travelling and classroom-based courses just stopped overnight. Even private in-house training courses for specific clients ceased, especially when countries started to close their borders. In fact, training had slipped way down the list of most companies’ priorities in the face of the pandemic. The global education business TES issued a stark warning in April 2020 that “Without support, training providers won’t survive” (Parker, K. 2020).

Thank heavens for the variety of online platforms that are now available for conferences and training. Having now worked with several, my own preference is Zoom. I also have to admit that online training does have its benefits. Yes, I have hooked up simultaneously with students in different parts of the world. No, I haven’t had to travel to deliver courses, which for some clients can add an extra day at each end of the course. Moreover, due to different time zones, I have been able to deliver two courses alongside each other in the same week – one in the Middle East followed by one in the US. Make no mistake, it’s hard work, but it can be done.

But there are downsides to the online approach. Although the feedback I have received has been just as positive as with the classroom delivery, I can’t always see the students, especially if they have their videos turned off. I am not always sure if they are even there, unless I ask questions or invite them to go to a syndicate room for an exercise. I guess for those individuals who would prefer to sit in the backrow of a classroom in the interest of remaining inconspicuous, being able to decide whether the course facilitator can see them or not must be very appealing. Moreover, we must not forget the real danger of ‘Zoom overload’, or the equivalent for other online platforms, which I guess is a variation of ‘death by PowerPoint’.

While I have mastered how to mute and unmute the students’ microphones, I am yet to discover how to turn on their videos. Perhaps that would be considered too invasive. But let’s be pragmatic about online training. If students and the course facilitator can all work effectively together in an online environment, just the cost savings alone for travel, hotel and the training venue could spell the beginning of the end of classroom training. When you add travel time to and from the training venue, the case for discontinuing classroom training gets ever stronger. I am sure this will not be lost on the army of accountants out there who will invariably be charged with minimising post COVID-19 business expenditure.

Coronavirus has been called a harbinger of change. So, among other things, perhaps that may mean the days of formal classroom training are numbered – RIP.

But then in December 2021, I experienced what was a ‘first’ for me. I travelled to Dubai where I delivered two courses on behalf of Meirc Plus – ICT Disaster Recovery and Crisis Management. The big difference was that I had attendees both in the classroom (wearing masks and adequately socially distanced) plus, online attendees simultaneously connecting using Zoom. Is this the future for commercial training?

13.8 The lost school productions

Author’s note

I can remember missing my youngest son’s school Christmas nativity play when he was about five years old. I was abroad on business at the time, but when I next spoke to him on the phone he said “Daddy, you missed my play”. The disappointment he conveyed because I had not been there was not lost on me. If nothing else, it made me feel very guilty as, despite his young age, that school play was really important to him, particularly as he was hoping both his parents would be there to support him. And so it is for children everywhere.

With that sentiment in mind, I was unsure whether to place this section within the ‘Impact on education’ chapter or ‘Performing arts’. However, by placing it here, I believe I have got as close as I can to straddling the two.

Westbourne House School is a co-educational day and boarding preparatory school located near Chichester in the UK. It caters for children ranging from age 2½-13 years old, and the pupils are split into year groups according to age. Margo Dodd (see section 14.5.4) is a freelance production manager, a role that includes wardrobe and prop design/management, set design, stage management, plus make-up and hair design. She has been involved in most of the school’s theatrical productions for the 7-13 year olds over a 12-year period.

Years 3, 4, 7 and 8 had been rehearsing all term for their respective school productions. They were scheduled to be performed in front of their parents and grandparents, four before and two after the 2020 Easter holidays. As we now know, these plans were unwittingly on a collision course with the proliferation of the coronavirus pandemic.

The six productions were split among the year groups with years 3 and 4 performing two each and years 7 and 8 just one a piece.

Except for Fawlty Towers and Oliver, which the school intended to stage in May and July respectively, all the performances were scheduled for the week commencing 16 March. However, with the country already plummeting towards lockdown and public gatherings being discouraged, the school opted to film the four performances using an iPhone, without audiences present. Copies of the recording were later sent to parents in MP4 format.

The year 3 performances were brought forward by two days, which placed extra pressure on the production manager. However, with the writing on the wall, both pupils and staff were starting to disappear and isolate, resulting in Jack and the Beanstalk being cancelled, at very short notice, at 8.25 am on the morning of the performance. Its remaining cast, still at school, joined the also depleted ranks of The Adventures of a Pirate Boarding School, which, along with the two Shakespeare plays, was one of the only three to go ahead that week. By the end of that week, the UK’s lockdown became official and, with the school now closed, all the staff and pupils had left. This excluded the offspring of key workers who were permitted to remain, along with the staff and their families who live on site.

The impact of cancellation on the children

There was extreme disappointment throughout the school, especially for the year 8 pupils who were leaving the school as the 2019-2020 academic year concluded. Quite apart from their all-important common entrance exams, these children, although resilient in many ways, like all children, will have suffered badly from the missed ambition, excitement and treats of their final term at the school. The grand finale should have been their year group’s annual staged musical, Oliver, and the much awaited prize giving at the end of it. This, and the absence of their final preparations before moving on to their senior schools, will have left a large hole in their young lives. The conclusion was that they were only given one day to return to school, collect their belongings and say farewell to all their teachers and friends before the official end of term in July. Loss of confidence, motivation and self-esteem was already in evidence, according to the school’s director of music. He had been trying to put on a ‘virtual’ concert of songs from the cancelled musical, but had struggled to get some of the children to co-operate with that alternative project. Generally, a fear of an unseen enemy and the uncertain future, together with instructions to distance from each other, not to share their belongings and to cover their noses and mouths in certain places were bound to have an adverse psychological effect, very possibly triggering an increase in anxiety and other mental health issues. Only time will tell.

Impact on backstage staff

The decision to bring forward the production date of any performance will invariably not be without its impact on the all-important backstage activity, overseen by the production manager. Margo Dodd’s business supplied many of the costumes and props for the performances.

For the year 3 productions, the two days lost meant seriously condensing the time originally planned for the final costume preparations, which literally needed round-the-clock dedication to make up that lost time. But then with Jack and the Beanstalk cancelled at the eleventh hour, much of the overnight effort was wasted and was replaced with a desperate a reshuffle of pirate costumes for a hastily reworked version of The Adventures of a Pirate Boarding School.

As costumier for the productions, Margo Dodd suffered a large financial loss, because of the ‘no-show, no-fee’ arrangement, particularly for the year 7 and 8 productions in the summer term, which were of course cancelled. A considerable number of costumes, shoes, props and furniture had been supplied (or were planned to be) from her own collection. This would have generated a handsome hire fee, along with costumes from two other organisations and a large quantity of props, furniture and set from the local theatre, and portable staging from another amateur group. This was lost revenue for them as well. Furthermore, other fees that were lost included the second instalment of her show fee for Fawlty Towers and full show fee for Oliver.

We find ourselves in an era where youngsters’ education has been seriously disrupted. After all the effort put into rehearsing, to also be deprived of the opportunity to see their respective school productions through to a natural conclusion, must be bitterly heart-breaking.

The impact of the pandemic on the performing arts is covered in more detail in the next chapter, especially for the amateur scene.