CHAPTER 7: LOCKDOWNS: SAVING LIVES, SHATTERING ECONOMIES

This chapter considers how different countries have approached lockdown. There are those that have adopted a very relaxed manner, while others have been extremely oppressive. Which are right and which are wrong, which are better and which are worse, will only truly become apparent when some kind of final post-pandemic analysis can be conducted.

“We isolate now so when we gather again, no one is missing.” An anonymous Haiku

In past pandemics, the world has experienced most of the social containment strategies we have seen deployed during COVID-19, but certainly not lockdowns on anything like the scale that have been endured during the COVID-19 pandemic. In addition to other countries around the world, at one point, much of China and all of India went into lockdown, meaning billions simultaneously found themselves in this state.

Let’s be clear, isolation does not kill the virus, but it can reduce the rate of infection. It has given rise to the word ‘Blursday’, meaning an unknown day of the week resulting from the disorienting effect of a lockdown. All that said, can this mass confinement of the world’s citizens really be justified? Taking different modelling approaches and using data from 11 European countries, both Imperial College London and the University of California, Berkeley, arrived at similar conclusions – the timely lockdowns executed in March 2020 served to save over 3 million lives in those countries.

“According to one [study] conducted by Imperial College London, wide-scale rigorous lockdowns imposed in March 2020 averted 3.1 million deaths in 11 European countries (including the UK, Spain, Italy, France and Germany).” (Schwab & Malleret, 2020)

While the ‘powers that be’ also argued that lockdown measures would contain the virus and save lives, there has been a cost to pay. The most obvious one is the effect on the global economy, which will invariably prove to be a millstone around the necks of future generations. Just how much of a burden will depend upon how long the pandemic lasts, although it is fair to expect a substantial rise in debt-to-GDP ratios across the globe. Furthermore, countries with high dependency on service industries, such as tourism and hospitality, are certainly at a disadvantage. Moreover, the effects on the economies of individual countries will also be determined by how successful each has been in containing the spread of the virus.

Reflecting on how economies and businesses are changing to combat COVID-19, Former World Bank Chief Economist, Paul Romer, remarked:

“An economy can survive with 10 percent of the population in isolation. It can’t survive when 50 percent of the population is in isolation.”

(Murray & Parkinson, 2020)

We have seen businesses go under, and many have lost their jobs. What is more, with many economies shrinking, it is also a bad time for youngsters entering the job market for the first time, as employment opportunities dry up. While there are of course those who have been protected by economic stimulus packages their respective governments have introduced, others have not had this protection. This is especially true of ex-patriot workers stranded in foreign countries, who have found they are not eligible to receive any form of local subsistence allowance. Just about the only recourse for many stranded ex-pats was to try and get home. This often necessitated travelling with the dwindling number of airlines still operating, which were often exploiting the situation by charging very inflated fares. Naturally, airlines would argue it is all justified by the principles of ‘supply and demand’.

From my own UK vantage point close to Manchester International Airport, I noted a massive reduction in the number of flights passing overhead. Even so, one constant has been the reliable, daily appearance of Qatar Airways, which has continued to operate a regular service unabated.

We must also not forget the collateral casualties from the pandemic with unrelated health concerns. Some have been reluctant to seek medical treatment for fear of being infected with coronavirus. Others had urgent hospital treatment delayed because health services had to switch their attention to addressing the COVID-19 onslaught.

Hospitals also denied patient visitor access and care homes adopted a similar policy. Although in the interest of reducing the serious threat from cross infection, it has caused much distress and heartbreak, especially when families were unable to be with loved ones in their final hours. And, we must not forget those individuals who have found the whole experience of lockdown a psychologically dauting situation to manage. To them, their front doors represented the entrance to a prison rather than a sanctuary.

Hundreds of people defied the coronavirus restrictions, gathering in Piccadilly Gardens in the UK city of Manchester in protest against England’s second lockdown. Many had arrived by coach from other parts of the country, and the crowd displayed a total disregard for social distancing and the wearing of face masks.

Arrests were made by Greater Manchester Police, whose resources were already stretched because 10% of the force were off work due to COVID-19 (Robson, 2020).

Finally, we have witnessed the polarisation of communities – some demanding the lockdowns continue to save lives, others insisting the economy is opened up to protect jobs. In some countries, large multitudes have taken to the streets in protest. Groups primarily, although not exclusively, consisting of millennials have also been observed blatantly ignoring local face covering and social distancing directives while they continued their social lives unabated.

7.1 Wuhan, China – The world’s first mass lockdown

This section is based primarily upon the account of a Chinese citizen who has requested to remain anonymous, and who regularly travels to Wuhan to visit an elderly relative. Arriving at the beginning of 2020, they planned to remain for just a few weeks, although with the intervention of coronavirus, their stay was extended by several months.

The capital of Hubei province, with a populace in excess of 10 million, Wuhan is the most densely populated city in central China. It is situated at the confluence of the Yangtze River and, its largest tributary, the Han River, approximately 750 kilometres west of Shanghai.

The story of the doctor unfairly dubbed the ‘Wuhan whistleblower’, Dr Li Wenliang, has been widely chronicled. On realising that patients being treated in Wuhan Central Hospital for a mysterious pneumonia were actually presenting SARS-like symptoms, he shared his concerns with his colleagues at the end of December 2019. In this supposedly private message, he encouraged his colleagues to take extra precautions to protect themselves from the infection. Despite requesting confidentiality, his concerns were widely circulated and were subsequently posted on social media. Although later completely exonerated, Dr Li was initially reprimanded and accused of spreading false rumours on the Internet. Sadly, he contracted the disease and died on 7 February 2020, aged just 33.

By mid-January 2020, rumours originating from the hospitals that a SARS-like disease was circulating in Wuhan started spreading among local residents. At that time, there had been no official mention of the situation, and in fact, the media and government dismissed the rumours as being false. Even so, hospitals had already started clearing the wards of patients suffering with less-urgent conditions. China, of course, had had first-hand experience of SARS in 2002-2003, and it was severely criticised on that occasion for what amounted to an attempted cover-up (Guardian, 2003). The British medical journal, The Lancet, reported that in the days before his death, Dr Li Wenliang was alleged to have said:

“If the officials had disclosed information about the epidemic earlier, I think it would have been a lot better. There should be more openness and transparency.” (Green, 2020)

In its report COVID-19: Make it the Last Pandemic – A Summary, TIP concurs with Green’s remark acknowledging that “valuable time was lost”. (TIP, 2021)

Before the enforced Wuhan lockdown, the virus spread rapidly, hospitals were at breaking point and PPE for health workers was in short supply. PPE manufacturers were calling their employees back from their Chinese New Year holiday break to meet the sudden surge in demand for their products.

Wuhan residents believe the actual death toll was far higher than the official figures suggested. This alleged discrepancy may have been driven by an official need to appear to be totally in control, a compelling aspect of the ‘face saving’ culture common in that part of the world.

New CDC figures appear to confirm that belief. When the agency tested 34,000 people in Wuhan for coronavirus antibodies, it found a rate of 4.43%. Extrapolating that figure across a city of close to 11 million people, that means nearly 490,000 people were infected, dwarfing the official tally of 50,354 cases (Sherwell, 2021). This would suggest that only 1 in 10 cases were recorded.

Initially, there was also no means of effectively testing people for COVID-19, as it was a novel virus. Meanwhile, two vloggers who referred to themselves as citizen journalists, Fang Bin and Chen Qiushi, using VPN, loaded several videos onto YouTube that documented what was happening in Wuhan. They recorded long lines of people seeking help at hospitals. The conditions inside were desperate and piles of body bags were seen in corridors as the mortuaries overflowed. By mid-February, Fang and Chen had ‘disappeared’ but, for posterity, their legacy remains on YouTube.

7.1.1 The lockdown

Following the outbreak of what we now know as COVID-19, Chinese authorities imposed a complete lockdown in Wuhan on 23 January 2020, in an effort to contain the spread of the novel virus. This included the suspension of all public transport, rail, major highways and air transport. The lockdown was eventually relaxed on 8 April 2020. But, in the hours leading up to the initial closing down of the city, an estimated 500,000 managed to beat the deadline and leave. It is highly likely that some took the virus with them.

Other Chinese provinces soon followed Wuhan and Hubei’s lockdown lead, resulting in an estimated 234 million quarantined in China alone. During this time, people returning to China from overseas were routinely quarantined in hotels for 14 days. In the event that 5 or less passengers on an inbound flight to China tested positive for COVID, flights to and from that destination would be suspended for one week. Up to 10 positive cases and flights would stop running for 2 weeks. More than 10 cases and flights would be suspended indefinitely.

It is usual in Wuhan for most residents to live in high-rise apartment buildings, sometimes with as many as 50 or more floors in which several hundred families reside. It is also quite common for several of these high rises to be grouped together in what can best be described as a gated community. When the lockdown started, these gated communities were locked and, unless they were classed as essential workers, no one was permitted to leave their apartments except to be taken to hospital. Every day, residents had to report their temperature to the community management team, which would normally have one person assigned to manage each high rise. This restriction remained in place for 76 days.

During the lockdown, local food stores were only allowed to sell to the nominated representatives of each community, who would also organise any medication that their community’s residents needed. This would be delivered directly to the residents’ apartments. Older residents were treated as a priority, and they would receive fish and meat free of charge. All non-essential shops, restaurants and cafes were closed.

With public transport suspended, volunteer car drivers and shuttle buses were introduced to enable essential workers, especially health workers, to get to their respective places of work. The day following lockdown, China deployed an extra 1,800 doctors and medical specialists from Beijing to Hubei province, along with PPE and medical supplies. Doctors from other parts of China followed later.

Post-Thanksgiving: Massive COVID case spike observed

Both national and religious holiday periods (such as the Chinese New Year vacation) can represent a major risk of seriously propagating a contagion during a pandemic.

In another example, while the estimates do vary, around four million US citizens are known to have travelled over the 2020 Thanksgiving holiday, resulting in a massive spike in new COVID-19 cases. On 26 November, Thanksgiving Day, at just under 162,000, the new daily case count appeared to be following a downward trend. However, by 11 December, that daily new case figure had risen to 248,000.

7.1.2 Relaxing of the lockdown

When the lockdown was relaxed on 8 April 2020, although they were discouraged from doing so, residents were permitted to leave their communities, but usually for no more than two hours at a time. They were clocked out and clocked back in again by their community officials. If they used public transport, they had to present their smartphone health code (see section 7.1.4) before being permitted to board. This had to be scanned on boarding and alighting to facilitate ‘track and trace’ activities. Should someone who was later diagnosed with COVID-19 have travelled on the same vehicle, this would establish exactly who was on the bus at the same time. Anyone who came into close proximity with an infected person would find their health code change from green to amber. Before the outbreak, buses would be driver-only, but a second crew member was added to validate the health check status of passengers before permitting them to board.

Despite the relaxation of regulations, those individuals wanting to shop or perhaps go to their bank would need to present their health code and have their temperature taken before being allowed to enter those premises. Moreover, without exception, if they were not wearing a face mask, they would not be permitted entry or for that matter be allowed to board a bus.13

7.1.3 Ten million tests in two weeks

During the second half of May 2020, China mounted a massive logistical operation in Wuhan, when every one of its ten million inhabitants was tested for the virus in a process that took around two weeks. Everyone had their test results returned within two days. With the exception of France, Germany, Italy, Spain and the UK, that is more tests than every European country had achieved in the first nine months of the pandemic. Furthermore, at least nine of the countries falling into that category have populations in excess of Wuhan.

Based apparently on a British concept, the swabs from the Wuhan exercise were tested in batches of ten at a time, and providing the combined test was negative, all ten individuals included in that batch would be flagged accordingly. If, however, the presence of the virus was detected, the ten people would be tested again individually, enabling any positive cases to be identified. The batch approach clearly increased the overall efficiency of the exercise.

7.1.4 The Alipay health code

Alipay is a mobile and online payment platform that was first introduced into Hangzhou, China, in 2004, and is now used extensively throughout the country. The company claims to have 1.2 billion users, which includes approximately 80% of the Chinese population (1.15 billion), plus international merchants who sell to Chinese consumers.

In 2020, Alipay introduced the use of the QR code to support the containment of COVID-19. By using the Alipay app on smartphones, a code turns ‘red’ for those who should be in quarantine. If you are waiting for test results or you have come into contact with a confirmed COVID-19 case, your code would be ‘amber’, otherwise, your code would be ‘green’. Individuals would need to provide data, such as their Chinese ID number, phone number, residential address and their place of work.

While the virus is in circulation, citizens will only be allowed to leave their communities if their health code is ‘green’. The New York Times conducted an analysis exercise of the software code and discovered that the app does far more than decide whether a smartphone’s owner poses a contagion risk.

“It also appears to share information with the police, setting a template for new forms of automated social control that could persist long after the epidemic subsides”

(Mozur et al, 2020).

The Times’s analysis found that as soon as a user grants the software access to personal data, a piece of the program labelled “reportInfoAndLocationToPolice” sends the person’s location, city name and an identifying code number to a server.

The majority of buildings, including work locations, public buildings and residential compounds have security guards in situ who are responsible for measuring the temperature of anyone entering. They are also expected to check an individual’s Alipay health code before allowing entrance. The 20% of Chinese citizens who do not own a smartphone are faced with a challenge, and they are generally dependent either upon their children or their local communities for support.

Although the introduction of the health code by Alipay has enabled China to relax lockdowns across the country, it has raised concerns from international human rights advocates. Known for its ‘Big Brother’ approach to controlling the population, the advocates fear that China will use the health monitoring software as a means to increase its ability to ‘manage’ its citizens.

7.1.5 The Wuhan stigma

As the lockdown was relaxed, people from Wuhan found it difficult getting work outside of Hubei province. Prospective employers were reluctant to employ anyone associated with what had been China’s epicentre for the virus. Prime Minister Li Keqiang encouraged people who had lost their jobs to become street vendors.

Broadcast by the BBC, ‘Three Years in Wuhan’, Episode three tells the story of a group of businessmen from Wuhan who, after lockdown had been lifted and with government approval, went on a trip to Hangzhou, Jiaxing and Shanghai. Software entrepreneur Huang Tiesen explains that on arriving in Hangzhou, they tried to book into a hotel but were turned away. At another hotel they managed to slip in, but on later realising where they were from, they were ejected by hotel staff at 5.00 am the next morning. In desperation, they hired a car and slept in that.

“It was very difficult when others started to blame Wuhan (for causing the pandemic) and call people here idiots. It was really hurtful because people outside didn’t understand what we were going through.”

Huang Tiesen (Three Years in Wuhan, 2020)

7.1.6 The positive legacy of SARS

China had first-hand experience of the 2002-2003 SARS outbreak, particularly as the virus is known to have originated in Guangdong province. Consequently, because of the connection to SARS, unlike some people in other countries, individuals in Wuhan took the COVID-19 outbreak very seriously, especially as many had personally experienced SARS. So, just maybe, that 2002-2003 outbreak had provided a rehearsal that the vast majority of the world did not get.

All that said, local Wuhan officials were slow to understand the gravity of the early reports of hospitalised people presenting SARS-like symptoms. Instead, Dr Li Wenliang was allegedly censored (Verna Yu, 2020), and the spread of the virus gathered momentum, while any chance, however small, of preventing its proliferation was lost.

7.2 Lockdowns, saunas and vodka

Despite the world having had some limited experience of dealing with coronaviruses before, we still have much to learn about the specifics of COVID-19, especially when a new mutation is discovered such as Omicron. Consequently, there is no precise model or playbook on which countries and organisations can base their pandemic plans, mitigation measures and contingencies. Therefore, it is hardly surprising that each country is for all intents and purposes ‘doing its own thing’ in whichever way it thinks is best. Their respective coronavirus lockdown ‘rules’, country by country, include the way in which they each report their COVID-19 confirmed cases and associated fatalities. This will invariably lead to some reporting inconsistencies.

Even so, we have learned from previous epidemics and pandemics that while the world waits for a vaccine, cure or an effective treatment for the coronavirus, isolation, quarantining and social distancing are all valid responses. Moreover, changes to social behaviour can also make a big difference, such as more frequent handwashing, not shaking hands or hugging and, as the French would say, ‘arreter de faire la bise’ – stop cheek kissing. The Māori traditional greeting of rubbing noses should be temporarily suspended, too.

In addition to observing a safe sneezing and coughing etiquette, we have been encouraged not to touch our face, because if we have somehow contaminated our hands, our eyes, nose and mouth are areas where viruses can easily enter our body. Some estimates show that we can touch our face as many as 20 times an hour. But, psychologist Natasha Tiwari explains “we can’t help it, it’s part of our DNA. We’re hardwired to do it”, (Tiwari, 2020).

Figure 13: Pictured wearing a mask that rather appropriately makes ‘A Pointe’ is Anne Jobson, ballet instructor at ‘Ballet for Adults’ in the UK city of Exeter

Regrettably, some countries were either too slow to adopt or even chose to ignore recommendations emanating from the WHO, such as the wearing of face masks and conducting extensive testing. With regard to face masks, I make no apology for saying what some may consider to be contentious.

It has been widely reported in several countries that there are those individuals who just refuse to wear masks, even to go into a shop. To me their actions are implying that they are quite happy to be inconsiderate and really don’t care if they share their germs with other people. I am equally sure that some of those individuals who claim that they cannot wear them for health reasons are not genuine. When all is said and done, there are those countries where the culture means that everyone unreservedly wears a face mask.

“Patients without medical conditions ask GPs for sick notes to exempt them from mask rules.”

(Diver, 2020)

Professor Martin Marshall, Chair of the Royal College of General Practitioners, has expressed his concern that doctors’ valuable time was being wasted by these frivolous requests. But as one UK nurse, very distinctly put it:

“Until you’ve done Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation (CPR) in scrubs, scrubs gown, plastic apron, FFP3 masks, visor, hood and two pairs of gloves, you should probably stop moaning about wearing a mask to the shops.”

Staying with the point regarding clinicians wearing face masks, hospital operating theatre staff will always wear them. Edwards nicely presents the rationale behind this when he remarked:

“Surgeons and nurses performing clean surgery wear disposable face masks. The purpose of face masks is two-fold: to prevent the passage of germs from the surgeon’s nose and mouth into the patient’s wound and to protect the surgeon’s face from sprays and splashes from the patient.”

(Edwards, 2016)

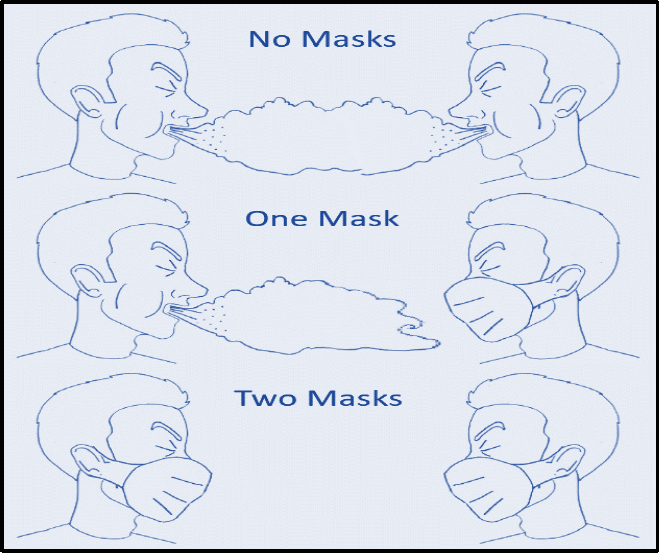

Figure 14: What a difference a mask can make Artwork: Geoffrey A. Clark

Enter the ‘COVIDiots’

One morning I heard a new coronavirus-spawned word while I was watching a Breakfast TV news programme – ‘COVIDiots’. Many airports and commercial airlines insist that travellers observe social distancing protocols and wear face masks continuously from the moment they enter their departure airport right up to the moment they walk out of their destination airport. This is as much for the safety of the individual travellers as it is to protect airport and airline employees.

The news programme reported that the face mask rules had been flouted on one particular flight from the Greek island of Zante to Cardiff, Wales. The flight was full and had around 200 passengers and crew onboard. One traveller said the flight was carrying several ‘COVIDiots’ who not only ignored social distancing while waiting to board, but wouldn’t wear masks while on the plane. Moreover, the cabin crew appeared inept and didn’t seem to care about the absence of masks. Another passenger claimed there “wasn’t much” policing of the rules. At least 16 of the travellers have since tested positive for COVID-19, and every passenger has now had to go into isolation for 14 days (BBC News (Wales), 2020).

When two people are not observing social distancing protocols, figure 14 illustrates how masks can help make a difference. When neither is wearing a mask, infection can more easily pass from one to the other. Where only one wears a mask, infection can still pass from the person without the mask to the person with. In the third case, where both are wearing masks, the possibility of either infecting the other is dramatically reduced.

And what is it with those people who insist on wearing masks that cover their mouths but not their nose? Perhaps they are unaware that, like their mouths, their noses are also connected to their lungs. By not covering both, they are defeating the object of mask wearing. For anyone in doubt, the WHO provides advice on its website about ‘when and how to use masks’.

Maybe this is the stuff of fantasy, but I keep coming across a report from the 1918-1919 Spanish flu outbreak. It claims that a special officer working for the US Board of Health shot a man for refusing to wear an influenza mask. The man apparently survived and after hospital treatment he was arrested for refusing to comply with the order. Could this happen today?

Born in 1933, the now 87-year-old June Selway remembers living through World War II. Immediately following the declaration of war, in the interest of their safety, many children were evacuated from UK cities. When comparing the air raids of the 1940s with the situation in 2020 and the fuss some make about wearing a face mask, June simply says:

“Try being evacuated from your home for years because of a blitz ... running to the air-raid shelter most nights. Just wear your masks ... it’s little enough to do.”

In the instance of the 2002-2003 SARS experience, tens of thousands were quarantined, which ultimately enabled the virus to be contained within a few months of the initial outbreak. That valuable lesson has clearly not been lost. With COVID-19, at one point in time, well over one billion people found themselves in a lockdown situation, sometimes of the most draconian nature.

The whole point of a lockdown is to contain the spread of the disease by instructing non-essential workers to remain at home. This, in turn, means fewer people are infected, and it reduces the impact on a country’s health services because of reduced numbers needing hospitalisation.

Having followed the media from several different countries in researching for this book, frequent reference has been made to the ‘R’ number, or the ‘reproduction number’. The UK government’s definition of ‘R’ is the average number of secondary infections produced by a single infected person.

An R number of 1 means that on average every person who is infected will infect one other person, meaning the total number of infections is stable.

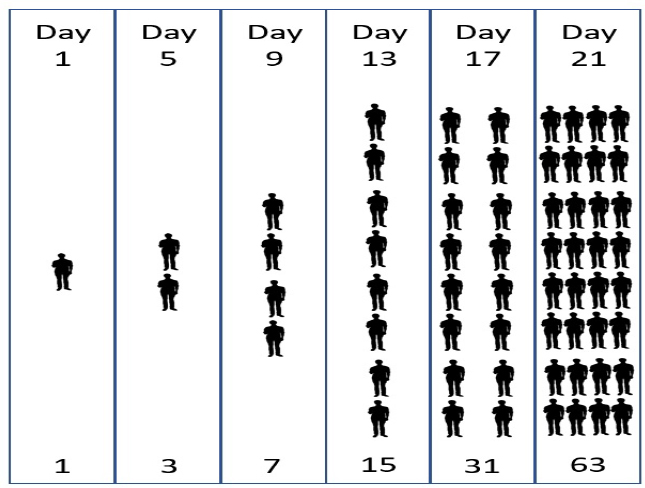

If R is 2, on average, each infected person infects two more people. In the following illustration, it assumes that R=2 and each individual who has become infected are themselves in an infectious state within four days.

Figure 15: Example of unimpeded spread of COVID-19 when R = 2

Using this model, by the end of the third week, 63 people will have been infected. If this situation is allowed to continue unabated and the number of confirmed cases approximately doubles every four days, after eight weeks, that infection count will be in excess of 65,000.

These conclusions do not allow for a ‘super-spreader’ occurrence, and the earlier example of the flight from Greece to Wales is a point in case. Likewise, the 26 September 2020 Amy Coney Barret White House ceremony resulted in 11 people subsequently testing positive (Annett, 2020).

R has changed over time.14 For example, it falls when there is a reduction in the number of contacts between people, which reduces transmission. Even so, by comparing various countries and their approach to lockdown, you will see variations. But, all countries should avoid exiting lockdown until R is less than ‘1’.

The first country to implement a lockdown policy was China, which was oppressive to the point that some may consider it akin to martial law.

“China’s coronavirus lockdown strategy: Brutal but effective.”

(Graham-Harrison & Kuo, 2020)

Around 50,000 were quarantined during the SARS outbreak in various parts of the world, including 18,000 in Beijing. However, on 23 January 2020, China kicked off its attempted containment of the coronavirus by locking down the 10 million inhabitants of the city of Wuhan, believed to be the origin of the outbreak. But, the lockdown coincided with the start of the Chinese New Year holiday. The country’s Outbound Tourism Research Institute estimated that more than 7 million international trips were planned during this period, while many more millions would also be travelling within China. So, had the genie already got out of the bottle and was COVID-19 spreading before the Wuhan lockdown?15

Public transport stopped, only food shops and pharmacies could remain open, and private cars were banned, unless granted special permission. Some residents were even banned from leaving their homes, and had to rely on suppliers delivering their provisions. Quarantined arrivals from overseas were also required to follow the ‘not one step’ policy, which meant they literally could not step over the threshold of their apartment or hotel room for 14 days.

A very uncompromising policy of door-to-door health checks was conducted by officials. Anyone suspected of being infected with COVID-19 was forced into isolation.

The wearing of face masks became ubiquitous across the country.

With the Chinese New Year holiday period coinciding with the start of the lockdown, industry effectively shut down in China. Organisations depending on a JIT supply chain model with products sourced in China, felt the effects of the spreading virus almost immediately. Both the UK-based Jaguar Land Rover and the Italian car manufacturer Fiat were among the first to express supply chain concerns.

The world also started scrambling to source PPE that was needed for protecting health workers from the virus. Moreover, countries that had stockpiled PPE of a type suitable for influenza, which included the UK, found this was inadequate when dealing with coronavirus. Much of the world’s supply was also made in China, although the global PPE shortage was further exacerbated when President Trump banned the export of PPE from the US. At the beginning of the pandemic, the UK was producing just 1% of its PPE needs. By August 2020, that number had increased to 70%.

Staying with the UK, its devolved parliaments defined the parameters for each of the four countries making up the union. Although they were similar, there were slight variations from one to another to reflect their specific circumstances. For example, beyond its larger cities, Scotland has an average of around 67 people per square mile in contrast to the more densely populated England which has 1,010. As for Northern Ireland, it shares a land border with the Republic of Ireland, which is not part of the UK.

The procurement and distribution of PPE in England proved a major challenge. In normal times, PPE would be distributed to 151 Primary Care Trusts (PCT). But, with the coronavirus outbreak, PPE use became essential in more than 58,000 locations that extended to doctors’ surgeries, clinics, residential care homes, nursing homes and dentists. This massive logistical nightmare was ultimately managed by the UK armed forces.

23 March 2020, Prime Minister Boris Johnson instructed all but essential workers in England to remain at home except for food shopping, medically related activities or to exercise for a maximum of one hour every day, such as walking in a local park. Gymnasiums, pubs, clubs and restaurants were closed, although those restaurants that could offer take-out food were permitted to continue trading.

Individuals who could WFH were naturally encouraged to do so. It should be stressed that the chief medical officers (CMOs) from each of the four UK countries remained in regular dialogue. Moreover, COVID-19 related experiences were also shared with the CMOs of other countries outside of the UK.

Foodbanks globally have seen a massive increase in demand. In the UK, a 59% rise has been experienced and Italy opened soup kitchens in its worst hit areas. Meanwhile, foodbanks across the US are under widespread and growing pressure as they cope with an increase in the ‘new needy’ amid the coronavirus pandemic ensuing unemployment (Lakhani, et al., 2020).

“Just as poverty has been a propagator of the pandemic, the pandemic has become a propagator of poverty.”

(Bryant, 2020)

Sweden’s approach to lockdown was more relaxed, and those bars and restaurants capable of ensuring social distancing were permitted to remain open. Conversely, when compared with the more favourable case and fatality counts of its Nordic neighbours, Sweden’s figures are less than impressive, and some have been critical of its seemly nonchalant cavalier approach to lockdown.

Swedish state epidemiologist, Dr Anders Tegnell, believes that the country will have achieved up to 40% exposure to the virus, while its Nordic neighbours will be around 1%. Dr Tegnell justified the relaxed approach explaining that Sweden believed that, before the end of May 2020, between 30-40% of the population would have been exposed to COVID-19. By reaching this goal, this would have achieved a high degree of ‘herd immunity’. (Tegnell, 2020).

That said, even allowing for any asymptomatic cases that have not been identified by testing, with the benefit of hindsight, it does seem that Tegnell’s herd immunity aspiration was somewhat over ambitious.

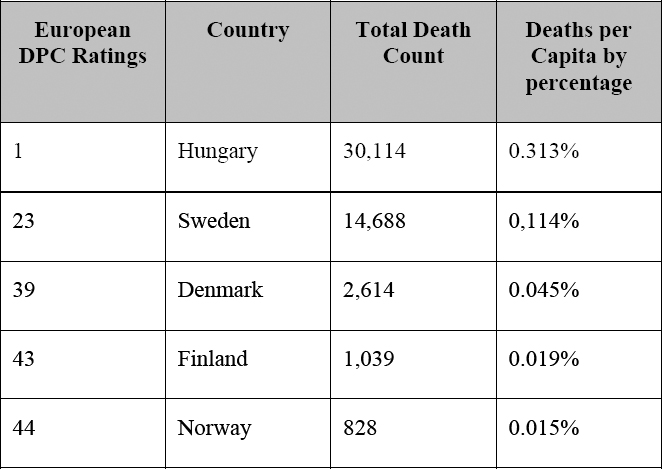

Although Sweden’s first wave seems longer than many other countries, it is possible that its more relaxed lockdown attitude may indeed pay dividends in the longer term. There have been examples around the world in a number of countries with citizens demonstrating against the lockdowns they are having to endure. Now Sweden, like other countries, is facing another pandemic wave, just maybe the Swedes will not be so lockdown weary as other nationalities might be. Even so, what a second wave that is proving to be which, before year-end 2020, its peak is more than ten times higher than its first. However, at just under 9,000 its 31 December fatality count is around 2% of its declared cases. But by mid-August, 2021, Sweden’s death rate was reported to be 10 times higher than its Scandinavian neighbours (Bendix, 2021). However, when compared across Europe by deaths per capita (DPC), Sweden was 23rd out of the 48 countries/provinces reporting.

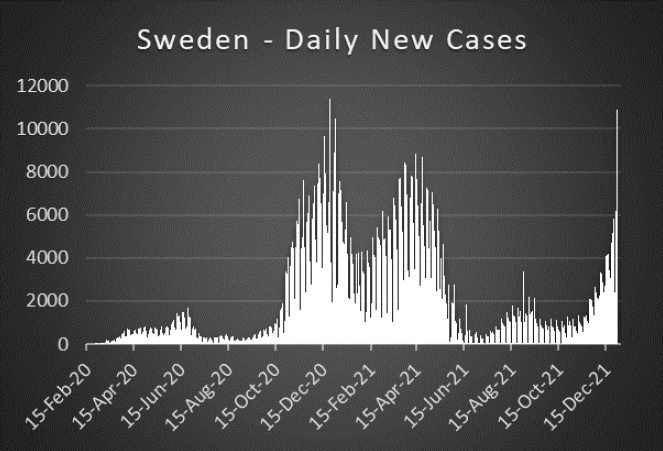

Figure 16: Sweden’s daily new cases as of 31 December 2021

In the Mediterranean island republic of Malta, initially, a €1,000 fine (approximately $1,175 US) was introduced for anyone caught breaking the COVID-19 quarantine regulations. This was subsequently raised to €3,000, and it was reported that, following spot checks conducted by the police, a Frenchman based in Malta had breached quarantine on five separate occasions. He was subsequently fined €9,000. Malta raised the fine for a third time offence to €10,000, and there have been no reported breaches since.

Failure to observe the social distancing rule of not meeting in more than groups of three was also enforced in Malta. This attracted a more modest fine of €100. By the end of April 2020, 645 fines had been recorded with 96 being issued for one single event.

On the other side of the world, the Australian state of Victoria wasted no time and declared a state of emergency on 16 March 2020. Meanwhile, Western Australia was fining people as much as $50,000 (circa US $35,000) and up to one year in jail for breaching mandatory isolation. In New South Wales (NSW), the same crime carried a less draconian $10,000 fine, with up to six months in jail. Not complying with social distancing could cost you a $1,000 fine. NSW later added a $5,000 fine for anyone deliberately coughing or spitting at an ‘essential worker’, with a repeat offence attracting a six-month prison sentence.

Still in Australia, 7-News reported that three young women were apprehended when trying to cross the border into Queensland, after two of them had previously tested positive for COVID-19 before leaving Melbourne. They were charged on 23 July 2020 with providing false or misleading documents plus fraud, and they face up to five years in jail plus hefty fines.

As Christmas 2020 approached, the UK ONS announced that more than 27,000 pandemic regulation-related fines had been given by police in Great Britain alone (England, Scotland and Wales). However, these fines were far from being evenly distributed.

“The 27,000 fines, mostly for gatherings, are not evenly spread geographically. Leicester has been under the longest-standing restrictions – yet it has a far lower rate of fines than north-west England, which has faced similar challenges.”

(Triggle, 2020)

The reality is that when confronted by the threat of rising COVID-19 case numbers, a country is generally dammed if it goes into lockdown and is dammed if it doesn’t. Taiwan is certainly one exception worthy of note.

A lockdown will invariably be to the detriment of a country’s economy and its non-essential businesses, while its population, although potentially better protected from the virus, can expect to suffer varying degrees of hardship. The more severe the lockdown, the tougher it will be on the economy, and millions may well find themselves nosediving into extreme poverty.

Conversely, if a country does not go into lockdown, that might be good news for the economy, but more of its citizens will be placed at a greater risk of becoming victims of COVID-19.

“We have seen leaders all around the world posturing, wanting to blame other countries or other individuals for what is happening.”

(Davidson, 2020)

Furthermore, some leaders just seem to be completely out of their depth and are struggling to manage the pandemic consequences that their countries are suffering.

While I am sure that every country will have their own stories about how good, bad or indifferent their leaders have been in handling the situation, initially, I want to focus on just two who have not had a good press.

The first is the Brazilian President, Jair Bolsonaro who presides over a population in excess of 212 million. Even though he tested positive for COVID-19 on 6 July 2020, he has been guilty of belittling the coronavirus, while telling supporters that it was nothing to worry about.

“In a televised address last week, he repeated a now well-worn phrase. “It’s just a little flu or the sniffles,” he said, blaming the media once again for the hysteria and panic over Covid-19.”

(Watson, 2020)

The tragedy is that by 31 December 2021, Brazil’s COVID-19 case count was over 22 million, while its corresponding fatality statistics are in excess of 600,000. Even so, on 16 April 2020, Bolsonaro sacked his Minister of Health, Luiz Henrique Mandetta, after he had urged people to observe social distancing and remain indoors. Mandetta’s replacement, Nelson Teich, resigned after only being in the job for one month, although without giving any reason for quitting.

To be quite cynical, Bolsonaro seems utterly determined to keep the economy open, but without any regard of the cost to Brazilian lives.

The second is Belarus President Alexander Lukashenko who has also taken a rather flippant approach to dealing with the pandemic. Belarus is a landlocked country bordered by Russia, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland and Ukraine. Its population is around 9.5 million, while the population density is 118 people per square mile (188 per square km).

Writing for Reuters, back in April 2020, Andrei Makhovsky reported that Lukashenko had stated that nobody will die from the coronavirus in Belarus even though, at that time, there had already been 26 fatalities in the country, and by 31 December 2021, over 5,500 had died.

“It was the latest show of defiance by the strongman leader, who has dismissed worries about the disease as a ”psychosis” and variously suggested drinking vodka, going to saunas and driving tractors to fight the virus.

In stark contrast to other European countries, Belarus has kept its borders open and even allowed soccer matches in the national league to be played in front of spectators.”

(Makhovsky, 2020)

To juxtapose the seemingly frivolous Bolsonaro and Lukashenko styles of pandemic management with a much more divergent approach, praise has been heaped on the way New Zealand (NZ) has managed the virus to date. Moreover, it has only ever recorded one case of SARS and no cases of MERS, so, it hardly fits the same profile as the South-East Asian countries that have had first-hand experience of a coronavirus outbreak.

Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern’s decision to close the border to non-national’s clearly helped the country make a good start in managing the situation.

NZ has a population of around 5 million and an average density of 46 persons per square mile. The distance from Australia, its nearest neighbour, is around 2,500 miles (4,000 kilometres).

The first confirmed COVID-19 case was diagnosed on 28 February 2020, and it closed it borders less than three weeks later, by which time the confirmed case count was still only 28. A State of Emergency (SoE) was declared on 24 March, in response to the case count having jumped by a factor seven to reach 208 in the five days since the border closure.

The SoE expired on 13 May 2020, when the country entered a National Transition Period that was due to last three months.

With the threat level raised to its highest point, ‘Level 4 – Lockdown’, it has meant that except essential workers, citizens have been instructed to remain at home barring vital personal movement (e.g. collecting food provisions or medical reasons, etc.).

Safe exercising was permitted within an individual’s immediate locality, although any form of travel was severely curtailed. All events and gatherings were banned, while non-essential businesses and public venues were closed down.

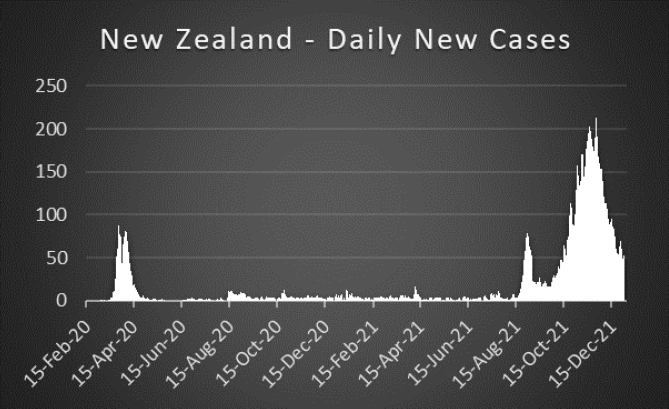

Figure 17: New Zealand’s first wave COVID-19 statistics, 31 December 2021

By year end, apart from its early but fairly modest first wave, by year-end 2020, NZ, like Taiwan, had very little to report. That was until August 2021 when a second wave began to develop. However, with the new daily case count remaining below 100, this certainly compares favourably with much of the remainder of the world. Even so, while still low compared with other countries, that daily count had doubled within two months.

But despite its early and apparent continued success, not everyone has been totally convinced with NZ’s pandemic management. Professor Patricia Davidson, Dean of Johns Hopkins University School of Nursing, believes that strong leadership during the crisis is essential and uses NZ’s Jacinda Ardern as an example. However, during a COVID-19: Psychological Impact, Wellbeing and Mental Health – Discussion Panel, she then went on to say that:

She may have a point about NZ, so let’s compare it with another island nation, Japan, which also made a good start.

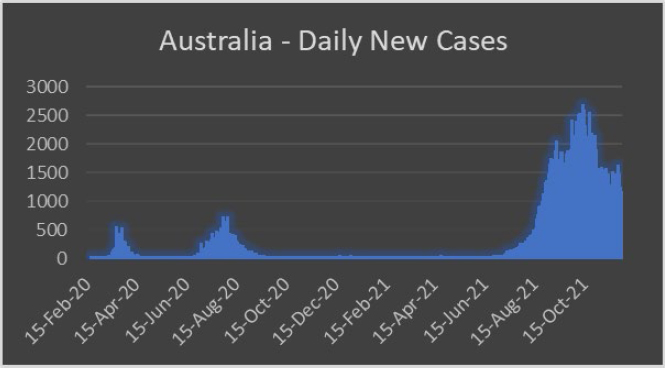

Like New Zealand, Australia also adopted what is best described as a nationalistic isolationist approach to the pandemic along with a low vaccination take up. It has tightly controlled its international borders and apart from two relatively minor surges within the first five months of the pandemic, its daily new case count (DNCC) has remained very low. However, as July 2021 arrived, the DNCC soared dramatically suggesting the country’s isolationist policy was no longer working effectively.

Figure 18: Australia’s COVID-19 statistics, 31st December 2021

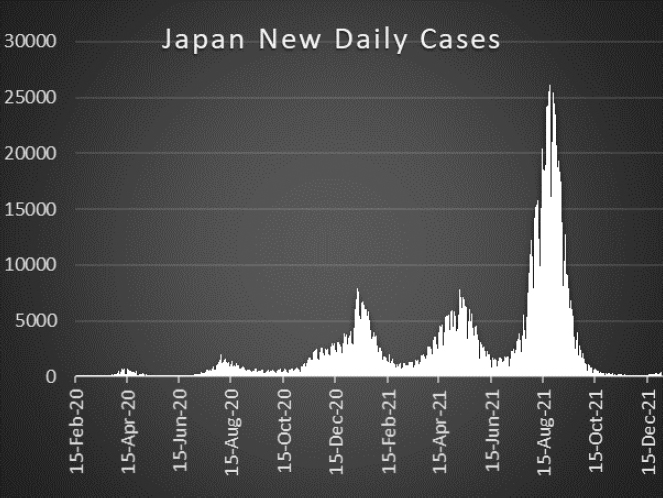

Similar to NZ, Japan is a group of islands, although at more than 126 million, its population is 25 times greater than NZ with only around 50% more land mass. But when you compare their COVID-19 case counts, Japan’s is only 16 times higher than NZ, and so has a much lower confirmed cases per capita. Rather surprisingly, Japan, as yet, has also not gone into a formal lockdown, and despite the disparity of population sizes, Japan’s testing count is only around 200,000 greater than NZ.

“When you look at Germany or South Korea, Japan’s testing figures look like they’re missing a zero.”

(Wingfield-Hayes, 2020)

No movement restrictions were placed on Japanese citizens and many businesses were permitted to remain open, including shops, hairdressers and restaurants.

There are certainly a number of circumstances that may have contributed towards helping Japan to be an early contender for one of Bill Gates’s ‘A’ grades for pandemic preparedness. However, there is no one obvious single factor that can be identified.

Before the coronavirus outbreak, Japan already had a track and trace process in place, although unlike other app-based approaches, Japan’s was analogue. Even so, while other countries had to design and implement a process and then train operators, Japan was able to hit the ground running. It is unclear whether this analogue process would be scalable or not should it be required to manage greater case numbers in a future wave.

There is also a school of thought that believes that Japan learned many early useful lessons when it was presented with the fait-accompli of having to manage the COVID-19 crisis onboard the Diamond Princess (refer to section 12.11.1). With the world watching on, having the virus arriving on your doorstep with an infected cruise ship docking in Yokohama, is certainly likely to have grabbed the attention of the local community.

Although there is evidence that obesity can be a factor in an individual’s chances of surviving COVID-19, Japan has one of the lowest obesity rates in the world, which is likely to weigh heavily in its favour. Even so, in mid-April, a SoE was declared in response to a spike in case numbers. Japanese local governments were granted the authority to ‘urge’ citizens to stay inside, but unlike other countries, they could not apply any punitive measures or legal force. The number of daily new cases noticeably reduced and the SoE remained in operation for one month.

During this time, citizens were encouraged by doctors and medical experts to follow the ‘Three Cs’. This meant avoiding:

• Closed spaces with poor ventilation;

• Crowded areas; and

• Close contact situations, such as close-range conversations.

Time reported that Mikihito Tanaka, a professor at Waseda University, said:

“You could say that Japan has had an expert-led approach, unlike other countries”

(Du & Huang, 2020)

With politicians being slow to react and take ownership of the crisis, perhaps Tanaka’s observations hit the right mark.

Figure 19: Unlike New Zealand, Japan has now had five waves

Regardless of which country you are in, the easing of restrictions should not be taken as a signal that the pandemic is over. As July 2020 arrived, something started to go wrong in Japan. Within a month of lifting its SoE, a new one had to be imposed. This ultimately led onto a third wave as year-end 2020 approached.

“Officials have begun to speak of a phase in which people “live with the virus,” with a recognition that Japan’s approach has no possibility of wiping out the pathogen.”

(Du & Huang, 2020)

The arrival of July 2021 saw not only the commencement of the delayed Olympic Games but also a rapid rise in new daily case counts. Even so, the Japanese government were insisting that there was no relationship between the games and the case count rise.

So, arguably, one of the few countries definitely in poll position to receive one of Bill Gates’s ‘A’ grades (see section 4.9) for pandemic preparedness has to be Taiwan, one of the six worst hit locations from the 2002-2003 SARS outbreak. It clearly learned the lessons to be gained from that experience.

Returning to the analogy used in section 4.9.4 of the pandemic being a marathon rather than a sprint, the reality is that countries will invariably find it necessary to impose more than one lockdown. Moreover, the actual size of a country may affect whether it impose constraints on discrete parts or applies restrictions to the entire country.

After it had relaxed its initial lockdown measures, in response to a spike of new cases, China locked down Beijing, a city of 20 million inhabitants. Similarly, in England, the city of Leicester (population 330,000) was locked down at the end of June, while the remainder of the country had largely relaxed lockdown. About one month later, the UK re-established restrictions to areas in the North West of the country, including Greater Manchester, in response to COVID-19 spikes, affecting around four million inhabitants. Australia has taken comparable action in relation to the city of Melbourne (population 4.5 million), in addition to imposing a night-time curfew. In Belgium, a night-time curfew order was also imposed on the city of Antwerp, with the threat of even the capital city of Brussels following suit.

Even into 2021 some countries introduced further lockdown measures, particularly in response to the rapid spread of the Omicron variant.

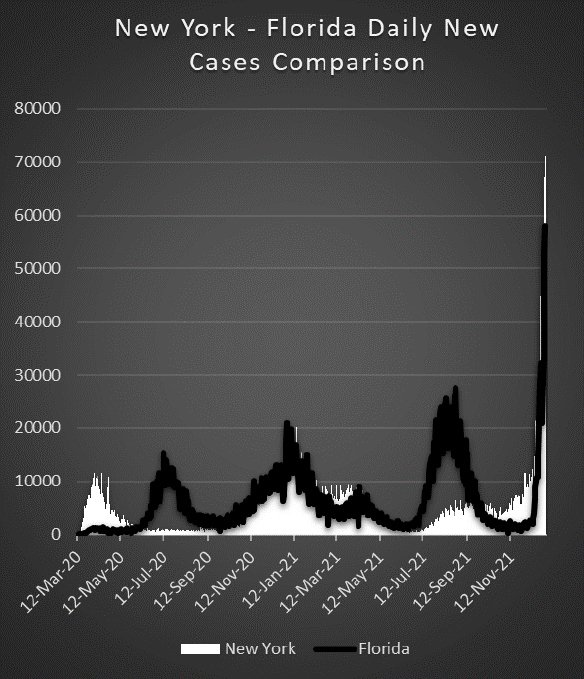

Figure 20: New York – Florida: Daily new case comparison

By making a comparison of two states in the US, New York and Florida, we can see as New York was exiting the first wave around the end of May, Florida was just entering. By year-end 2020, both states had entered a second wave almost alongside each other. Likewise, both states simultaneously entered a third wave although the Florida daily new case count was far more severe than New York’s. In fact, Florida’s DNCC figure was approximately five times that of New York. Even so, despite the comparison of the two sets of pandemic waves being largely out of sync, it is noticeable that the late 2021 Omicron arrival seems to be affecting both states simultaneously.

As the pandemic ebbs and flows, in response, lockdowns will be relaxed or intensified. Rather worryingly, there are those people who seem to be deluded that once the lockdown in their respective countries has been relaxed, that’s it – the pandemic is over. There are also those individuals who prefer to bury their heads in the sand and pretend the pandemic isn’t really happening. Should they choose to ignore their government’s COVID-19-related regulations vis-à-vis staying at home, washing hands, social distancing and wearing face masks, although they may not suffer the consequences of their actions, others might.

What is also likely to have helped proliferate the spread of the disease were the number of demonstrations that have occurred in various countries since the pandemic started. Some targeted local lockdown regulations, while others were totally unrelated, such as the ‘Black Lives Matter’ protest supported in several countries.

‘Don’t kill granny!’

Whatever little children call their grandmothers – granny, grandma, nanny, etc. – it is still the same person. In August 2020, the UK city of Preston re-entered lockdown after a spike in COVID-19 cases was detected. With half of the people who tested positive being between 18 and 30 years old, the leader of the city’s local government issued a stark warning to these youngsters – ‘Don’t kill granny’. Although young people are statistically less likely to present any serious symptoms, they can still pass the infection on to other, more vulnerable people.

In a separate example, using around 20,000 volunteers, the UK Biobank has been undertaking a study into how COVID-19 spreads. This organisation describes itself as being a major national and international health resource, and a registered charity. Its aim is to improve the prevention, diagnosis and treatment of a wide range of serious and life-threatening illnesses.

Although the Biobank study is still in progress, early results have indicated that antibodies have been detected in 1 in 14 of the participants. This means they have unknowingly had COVID-19 and were probably asymptomatic. These early results also indicate that the biggest group by far falling into this category, like the city of Preston, are in the 18 to 30 age range. If they also belong to the gung-ho ‘COVID-19 won’t get me’ brigade, then the coronavirus version of the children’s fairy-tale ‘Little Red Riding Hood’ (Guenthier, 2020) may well apply to them.

Those of you familiar with the fairy-tale will appreciate the parallel of a pandemic-themed cartoon I recently saw. A little girl was walking through the woods on her way to her grandma’s house when she came across a wolf called ‘Coronavirus’. Confronted by the wolf, the little girl stood her ground and said “I’m not afraid of you, Mr Wolf”, to which the wolf replied “Oh, I’m not interested in you little girl, I just want to follow you to Grandma’s house”.

So, who was ultimately infected with coronavirus in this variant of the story? Of course, it was grandma.

7.3 You can’t rob us of our rights and our liberty

Many of the major democracies around the world, although not all, have been struggling to manage the pandemic crisis without upsetting the voters who elected them in the first place. That is a difficult achievement, even on a good day, because as the saying goes, ‘you cannot please all of the people all of the time’. Politicians invariably want to be re-elected when their term in office comes to an end. Consequently, doing or saying anything that has the potential to upset the electorate is a big ‘No-No’.

However, in the midst of the pandemic, for some it has become an impossibility, especially when the question of what to do about Christmas had arisen. Although every country that celebrates Christmas will regulate what its citizens can and cannot do, very few countries approached it in the same way. That is not unreasonable if we remind ourselves of the old adage: ‘one size does not fit all’.

As year-end 2020 approached, an increase in new cases of COVID-19 was being witnessed across much of the world. With Christmas celebrations in mind, a variety of actions were being taken, and some examples are as follows:

• Germany and the Netherlands would be in lockdown.

• Italy originally had cancelled Christmas markets and imposed a 10.00 pm to 5.00 am curfew. But with less than a week before Christmas, the country opted to join Germany and the Netherlands re-entering lockdown.

• France relaxed travel restrictions over the holiday period.

• Russia told elderly citizens to self-isolate.

• Spain permitted travel and limited gatherings.

• Originally, the UK proposed introducing temporary ‘Christmas Bubbles’, allowing up to three households to celebrate together over a five-day period. The devolved governments in Wales and Northern Ireland imposed tighter controls because of a dramatic rise in new cases. However, one week before Christmas, by which time the new case counts were rising rapidly across all four UK countries and a new variant of the virus was emerging, tighter restrictions were introduced. Prime Minister Boris Johnson announced that the planned relaxation of COVID rules for Christmas was to be scrapped for large parts of south-east England and cut to just Christmas Day for the rest of England, Scotland and Wales. Around 18 million people in London and the south east were effectively placed into lockdown. A further six million people, primarily from East Anglia and Hampshire, were expected to be added to these tighter restrictions on 26 December, in response to further rapid proliferation of the virus variant.

To antagonise the situation, French President, Emmanuel Macron, banned all travellers from the UK from entering France for fear of the new variant of COVID-19 spreading. Massive traffic jams resulted in both Dover and Calais, with thousands of commercial vehicles being trapped as both Eurotunnel operations and ferry crossings between the two countries were initially suspended. However, by 28 December, cases of the new variant were being reported worldwide.

• In the US, each state was defining its own restrictions. By mid-December, 22 states had travel restrictions imposed and many had up to 14-day quarantine in place. With the country still reeling from the Thanksgiving-associated spike in new cases, Christmas travel was expected to be more than double.

In the UK, in July 2020, the government imposed extra restrictions immediately before Eid al-Adha. In effect, this deprived the British Muslim community of one of their major religious festivals. At that time, the new daily case count was well under 1,000 while by mid-December, it was hovering around the 25,000 mark. Had Prime Minister Boris Johnson allowed Christmas to proceed as originally planned, this would have been seen by many as discourteous and hypocritical.

So here is the challenge. On the one hand there were those who believed Christmas should be severely curtailed or even cancelled, thereby depriving the virus of an excellent opportunity to proliferate. There is certainly some very strong evidence supporting this argument, especially when we consider the spiralling numbers being hospitalised by COVID, long before the festive season. Some health services were already stretched to their limits and those in the northern hemisphere would also have the fallout from seasonal flu to contend with.

The BMJ and the Health Service Journal (HSJ) jointly issued a warning that the easing of the UK COVID regulations for the Christmas holiday period “would cost many lives” (Godlee, 2020 and McClellan, 2020).

In referring to the BMJ and HSJ’s joint statement, BBC reporter, Chris Mason, remarked that any tightening of the regulations may be seen by many as: “Robbing us of liberties that we take for granted.” (Mason, 2020). This is, of course, a luxury that the citizens of those more autocratic countries do not necessarily enjoy.

Mason’s remark takes us to the other side of the argument and those who maintained that Christmas should be ‘business-as-usual’.

Those NGO’s whose raison d’être is to champion a nation’s civil liberties would understandably argue that governments have an obligation to protect people’s lives which seems reasonable to me. This would naturally be expected to continue during a public health emergency such as the coronavirus pandemic. However, when this also involves imposing restrictions on the populace, some might consider that it erodes civil liberties. In such instances, NGOs would invariably be quick to react by protesting in the strongest possible terms.

In response to the UK’s Coronavirus Act, 2020, which granted the government emergency powers, one such UK based NGO, was Liberty. It proposed its own alternative Bill to be put before parliament entitled “Support Protecting Everyone” (Liberty, 2021). While this Bill looks to curb pandemic related government emergency powers, it also seems to be using the coronavirus as a smokescreen to address issues that would have existed even if the pandemic had never happened. Moreover, in my opinion, some of Liberty’s demands are in direct conflict with a number of measures put in place to help keep people safer.

But organisations like Liberty should remember that in a democracy, a government is elected to run the country and they should be allowed to do so in whichever way they see fit. It will ultimately be the electorate that are subsequently allowed to decide, via the ballot box, whether they have or have not done a good job. It was Winston Churchill who reminded us that “no one pretends that democracy is perfect”, but it is the best thing we have.

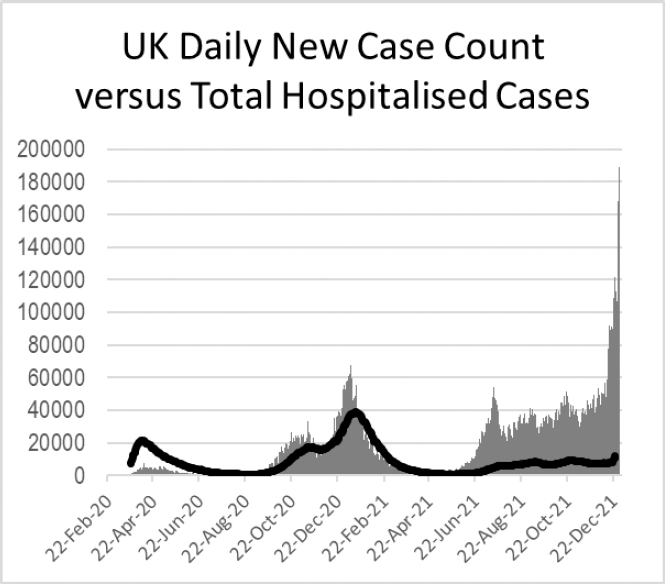

Figure 21: UK – Daily new case count versus total hospitalised

Figure 21 shows the UK’s DNCC with the black line indicating the number admitted to hospital with COVID-19.

What is very noticeable is the UK’s daily new case count on 25 December 2020 was 32,705, although 11 days later on 6 January 2021, this had almost doubled to 62,322. Although the Christmas holiday break undoubtedly played a part in this surge, so too did the new coronavirus variant discovered in the UK, which spread at an alarming rate.

Running alongside the 2020 post-Christmas DNCC surge was the UK’s vaccination programme. In Figure 21, it is noticeable that as the third wave commenced in July 2021, while hospital cases rose, they did not rise anywhere near as sharply as they had done during the second wave. This was attributed to the extensive vaccine take-up by the population. The alarming increase in daily new cases caused by the Omicron variant is clearly visible.

7.4 Running a business during lockdown

There will be some businesses that by their very nature will not be able to operate during a lockdown regardless of its severity. Whether they survive a pandemic could depend upon a number of factors. The scope and conditions attached to any economic stimulus packages that their respective governments may choose to introduce will be a major influence. Almost undoubtedly, the economic consequences of COVID-19 will be shrinking economies and potentially a major global recession, synonymous with business failures and mass unemployment.

UK Chancellor Rishi Sunak’s ‘Eat Out to Help Out’ incentive designed to help the struggling hospitality sector was used more than 150 million times in 84,000 restaurants during August 2020.

During a Downing Street press conference, 26 March 2020, UK Chancellor of the Exchequer, Rishi Sunak announced the country’s unprecedented furlough scheme. This was designed to support workers whose jobs were at risk due to the pandemic. Initially 80% of salaries of circa 10 million UK workers would be paid by the government. However, Sunak added the caveat:

Employee with Type-1 diabetes dismissed for self-isolating

Following her doctor’s advice, the plaintiff, Mrs Jackie Reid, self-isolated at the beginning of the pandemic as her condition made her more vulnerable to the virus. Her employer claimed that by self-isolating she was in breach of her contract.

An industrial tribunal found in favour of the plaintiff awarding her substantial damages. Although the law will obviously vary from country to country, employers should familiarise themselves with the rights of both themselves and their employees under their local employment law (Shaw, 2020).

Sadly, each month since the pandemic was declared, we have seen companies collapse while others have shed employees in an effort to survive. For many organisations we have seen ‘business-as-usual’ become ‘business-as-survival’, and many simply have not made it. Some were already struggling economically before the pandemic. One early victim was the UK airline Flybe that found the pandemic to be the proverbial straw that broke the camel’s back. It collapsed to the detriment of its supply chain, while leaving a substantial hole in UK and European intercity travel options.

There have been outcries on both sides of the Atlantic because a UK government agency used a photo of a dancer by the name of Desire. The appended caption read “Fatima’s next job could be in cyber (she just doesn’t know it yet) – Rethink. Reskill. Reboot”. US photographer Krys Alex said she was ‘devasted’ that her work was used in this way, suggesting that the dancer should retrain. Although the UK Culture Secretary, Oliver Dowden, had the picture pulled, describing it as ‘crass’, the damage had been done and the post had already gone viral on social media (Djudjic, 2020).

But let’s step back and look at the reality of the bigger picture. Firstly, if someone loves their chosen career, it is tragic if circumstances, such as this pandemic, mean they can no longer follow their dream. But this stretches far beyond the performing arts, which I will talk about later in the book. The reality is that there are many people around the world who have trained for a specific profession and now find themselves out of work, some with little or no prospect of finding similar opportunities. Today we are pointing fingers at the pandemic as being the root cause, but we have seen some professions all but disappear in the past simply because society no longer needed them, or automation has made vocations obsolete. We have witnessed blacksmiths largely replaced by motor mechanics, and chimney sweeps by central heating specialists. Others have virtually vanished, such as thatchers, switchboard operators, hot metal typesetters, typists, railway signalmen and elevator operators. Even before the arrival of the twentieth-century, powder monkeys and climbing boys had long since disappeared and the days of the lamplighters were numbered, too. In fact, the World Economic Forum believes that:

“The Forum estimates that by 2025, 85 million jobs may be displaced by a shift in the division of labour between humans and machines.”

(Whiting, 2020)

We also see businesses change because of technological advances and improvements in our ability to communicate. For example, news of the 1805 British naval victory at the Battle of Trafalgar took more than two weeks to reach London, a distance of 1,500 miles (2,350 km). It would have taken around three months for that same message to have travelled to Australia, but 100 years later in 1905, it would have taken less than seven hours. Today, it is virtually instantaneous. More recently, enhanced technology has facilitated the increased popularity of online banking, resulting in the closure of some high street bank branches, along with the redundancy of their staff.

On a personal level, had I wanted an appointment to see my doctor in 2019, I would have phoned the surgery and turned up for a face-to-face appointment at the agreed date and time. In the early days of the pandemic, a number of doctors’ surgeries were contaminated with COVID-19. So, now in 2021, although I still phone for an appointment, my initial consultation may well be via video call. In the UK, it was always the intent to embrace technology in this manner, but the arrival of coronavirus has certainly expedited the project.

As mentioned in section 7.1.5, the Chinese Prime Minister Li Keqiang has been encouraging the unemployed in Wuhan to become street vendors. You could argue that this would be insulting to anyone who is highly skilled and qualified for a specific career. While there are of course others, one group of professionals who have had to endure some serious culling have been airline pilots. For the foreseeable future, the ever-growing yoke of redundant pilots will be chasing a rapidly shrinking list of opportunities.

According to CNBC, US airlines alone ended the year 2020 with 90,000 fewer workers due to pandemic related redundancies. However, twelve months later, pilot hiring numbers are surpassing pre-coronavirus pandemic levels.

Another group that seems to have become an endangered species in certain parts of the world are English Language teachers. Students have not been travelling to destinations that specialise in offering English as a Foreign Language, primarily to millennials (see section 13.4).

But, invariably, it will be hospitality, events, leisure, entertainment, gymnasiums and tourism that will be among those to suffer most, along with non-essential retail outlets. Other businesses that depend upon offering clients a close contact face-to-face service, such as hairdressers, beauticians and massage parlours are also likely to suffer a similar fate. Moreover, those organisations that expect any business interruption insurance (BII) policy to cover losses may be in for some serious disappointment (refer to section 11).

Each country dictates its own lockdown regulations, and as you will have read in chapter 7, some have been extremely draconian, while others were comparatively relaxed.

Furthermore, every business, large or small, should realise that when a crisis occurs, there will be no moratorium on other crises occurring simultaneously. For instance, we only need look to Australia. During the 2019-2020 southern hemisphere summer period referred to locally as ‘Black Summer’, Australian emergency services had to deal with unusually intense bushfires, flooding and COVID-19. When breaking the impact down from national level to an individual business viewpoint, there will have been some organisations that may have been adversely affected by two if not all three of these crises. Similarly, at the time that COVID-19 began its rampage across the US, several severe outbreaks of wildfires started far earlier than usual in California, while outbreaks in Oregon were unprecedented. Moreover, the Southern States have had to contend with the consequences of hurricane damage, starting with Laura, which made land fall in August.

As we have seen in chapter 7, lockdowns came in a variety of shapes and sizes from the harsh draconian measures enforced in China to something like the more relaxed Swedish version. Or, as in the case of Taiwan where they have avoided the need to lock down all together. So, which approach is right, and which is wrong?

Let’s just recap for a moment and remind ourselves why we really need to have these lockdowns. Simplistically put, if everyone is isolating at home, then the virus cannot spread. This is how SARS was contained in 2002-2003. But, the consequence of everyone isolating at home for long periods is that the global economy will go into meltdown.

“Virus is like a huge sink hole in global economy. No one (not even anyone on this chat!) knows how big/deep it is. And every day world in lockdown it gets bigger and deeper.”

(Paumgarten, 2020)

Getting the balance right between saving lives and protecting the economy is a major challenge that I believe is a potential oxymoron. There are also some ‘politicians’ around the world who have been behaving as though their primary concern is avoiding doing anything unpopular, which could result in them not being re-elected. Time for them to wake up and smell the coffee, although for some, maybe it’s too late already!

Until such time as the WHO declares the pandemic is over, exiting a lockdown does not mean that the virus has gone away. Nor is it safe just to pick up life where it was left off before coronavirus arrived on the scene. Sadly, I have seen evidence that certain sections of society in several countries are behaving as though it is all over. Others seem in denial that the pandemic has actually happened. The number of people that can gather together in social groups is dictated by individual countries.

International Labour Organisation – 23 September 2020

The devastating losses in working hours caused by the COVID-19 pandemic have brought a massive drop in labour income for workers around the world.

Excluding any income support provided by respective government measures, the first three quarters of 2020 have witnessed a 3.5 trillion USD drop in income compared with the same period in 2019 (ILO, 2020).

Even so, there are those individuals, primarily, although not exclusively, in the 18 to 30 age range, the millennials, who act as though these restrictions do not apply to them and it’s ‘party time’. They will pose a constant societal COVID-19 proliferation threat all the while they choose to ignore what is their social responsibility. Such situations are far less likely to occur in countries such as China where the government is completely intolerant of dissent.

There have been many references to the ‘new normal’, but what exactly does that mean? Is it real or some kind of illusion, like a mirage in a desert that we think we can see but never actually get to? I believe we will not be able to accurately describe what it looks like until we have actually arrived, which in itself begs the question:

“Will the new normal be our final destination or just a transient state?”

What we can safely assume about this ‘new normal’ is that it could necessitate changes to the way we conduct both our personal and professional lives. Moreover, it probably means that every time the ‘R’ number swings in the wrong direction, locally or nationally, some kind of lockdown measures may well follow. How often will the economy need to be closed down, partially or totally, necessitating that we run for cover, seeking the sanctuary of our homes. For the time being, that is the ‘new normal’ and what we need to learn to manage both societally and professionally.

There are, of course, some serious issues that will need addressing before we can finally reach that harmonious destination of Shangri-La when we can genuinely believe that the worst is behind us. They will invariably include some key questions such as:

• Will scientists have discovered a vaccine or a cure? There was certainly some very encouraging news since Q4 2020. with several vaccines being approved. But, will those vaccinated still be capable of carrying COVID-19 droplets in their nose? Although they are far less likely to be infected by COVID-19, they could still be infectious to others who have not been vaccinated. Will any immunity provided by vaccination continue to be effective if the virus mutates, or will annual COVID vaccinations become a feature of the future, just like seasonal flu vaccinations?

• Is there some kind of treatment that may allow us to downgrade COVID-19 from a potentially fatal disease to a chronic but treatable illness? HIV/AIDS is a classic example.

• Has just about everyone on the planet been exposed to COVID-19 and the virus has nowhere else to go? Although, hang on! Reports have been appearing about people being re-infected. Are these just isolated cases or, given time, will any post-COVID acquired immunity gradually dissipate?

What we do know is that COVID-19 has already proved to be a massive agent of change. But haven’t we been here before? Didn’t we have to come to terms with a ‘new normal’ after World War I, then again after the Spanish flu, not to mention the Great Depression, World War II, the Cold War, the 2007-2008 financial crisis, the ever-growing cyber threat and, in the European Union, Brexit? I believe that, in reality, while the availability of a vaccine, cure or treatment will be key factors, we will pick ourselves up, dust ourselves off and just get on with whatever personal and professional parameters that life presents us.

One of the effects of the pandemic has been on town and city centres, which have, in some cases, been likened to ghost towns. Shops and hospitality outlets depend upon passing trade, but the footfall has been so low, especially with so many workers becoming home based. It is true to say that the traditional ‘high street’ has been slowly disappearing in recent years, threatened by the ever-growing presence of online alternatives. This has certainly accelerated since March 2020 because of pandemic lockdowns. Those independent shops and chain stores without an online side to their business have been particularly disadvantaged. Even when lockdown regimes have been relaxed, there has not been an automatic restoring of the ‘status quo’, and it is already apparent that some businesses will not be reopening. In the UK, the head of the Confederation of British Industry (CBI), Dame Carolyn Fairbairn, pointed out that local businesses from dry cleaners to sandwich bars depend upon the country’s offices.

Reports from Japan indicate that Fujitsu will halve its office footprint within three years, as WFH will become a standard option that employees can choose. I worked for Fujitsu Consulting for a number of years, and along with many of my colleagues, I was home based as far back as 1997. Using a hot-desk system, I only went into a Fujitsu office if I had to attend a meeting or needed to replenish my home office supplies. Today, with the multitude of online conferencing platforms, maybe going into the office for meetings will also become a thing of the past.

Meanwhile, Twitter has told employees that, if their role permits, they can WFH ‘forever’ if they wish, as it reassesses its post-pandemic corporate estate requirements.

7.4.1 Dealing with extensive absenteeism

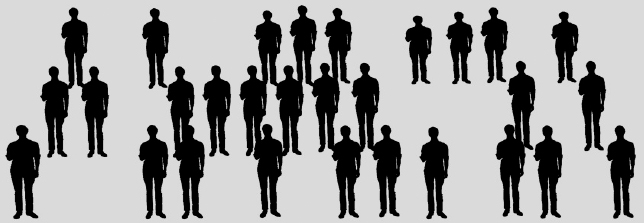

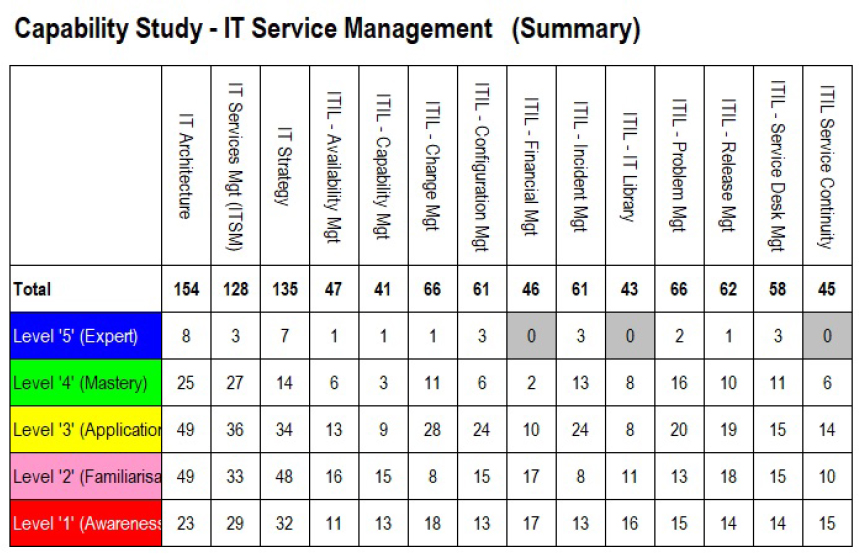

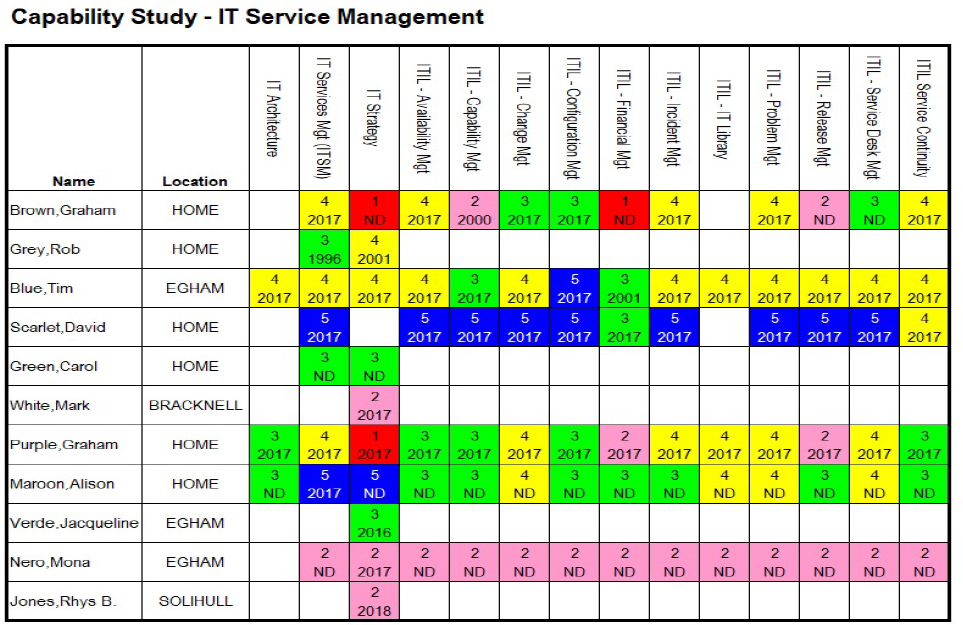

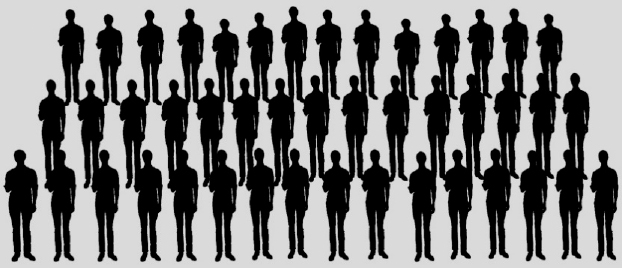

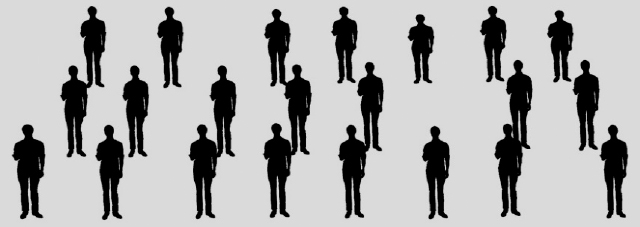

Consider for a moment that your organisation might look something like the one portrayed in Figure 22, which in this example has 45 employees. Could you manage if it was decimated16 by a pandemic and looked more like the line-up in Figure 23? Furthermore, absenteeism will invariably be decided at random, possibly robbing you of key employees.

Figure 22: Your organisation might normally look like this

Figure 23 would see your workforce reduced by 35%, from the original hypothetical number of 45 down to 29 employees. The figure of 35% absenteeism could rise or fall depending on the severity of the pandemic. However, the potential effects of social distancing may well be contingent on the nature of your business and your working environment. You may find that these regulations may decimate your workforce still further taking it down to 23 (see figure 24), almost one half of its original size. Moreover, if your premises are open to your customers, you may find you have to restrict the number that can enter at any one time.

Figure 23: Absenteeism could reduce your organisation to this

Figure 24: Social distancing could cripple your organisation

By the summer of 2021 here in the UK, we were seeing businesses suffering from staff shortages especially in the hospitality, transport and food industries. This situation was further compounded by year end as both public and private sectors began to suffer significantly from COVID-19 related absenteeism.