CHAPTER 2

MDM: Overview of Market Drivers and Key Challenges

In the first chapter of this book, we discussed the reasons for and the evolution of Master Data Management and Customer Data Integration. We also offered a working definition of MDM. Specifically, we defined Master Data Management as the framework of processes and technologies aimed at creating and maintaining an authoritative, reliable, sustainable, accurate, and secure data environment that represents a holistic version of the truth for master data. Master data are those entities, relationships, and attributes that are critical for an enterprise and foundational to key business processes and application systems across multiple lines of business.

We stated that MDM in general and its variants such as the customer-centric version known as Customer Data Integration and the product-centric version often referred to as Product Information Master are especially effective in modernizing a global enterprise, and that the need for an authoritative, accurate, timely, and secure “holistic version of the truth” is pervasive and is not particular to a specific industry, country, or geography.

We also mentioned that Master Data Management, although evolutionary from the pure technological point of view, is revolutionary in its potential business impact and represents a particularly interesting opportunity to any business-to-consumer (B2C), government-toconsumer/citizen (G2C), and even business-to-business (B2B) entity.

Using all these factors as background, we are now ready to focus on a business view of MDM and discuss the reasons for its rapid proliferation, the challenges that its adopters have to overcome in order to succeed in implementing MDM initiatives, and the way the market has been growing and reacting to the demands and opportunities of MDM.

Specifically, this chapter will concentrate on the following subjects:

• Market growth and adoption of MDM

• Business and operational drivers of MDM

• Challenges of MDM

We will also focus on the ability of MDM solutions to help transform an enterprise from an account-centric to a customer-centric, agile business model.

Market Growth and Adoption of MDM

MDM is rapidly maturing and its adoption is growing strong. In the first edition of this book, published in 2007, we referenced a survey conducted by The MDM Institute (www.tcdii.com). The survey found that 68 percent of Fortune 2000 companies were actively evaluating or building MDM solutions. The adoption of MDM was much lower outside of these 2,000 large companies. At that time the survey focus was on both business and technical aspects of MDM. The survey tried to weigh the potential benefits of implementing an MDM platform against the cost, implementation, and operational risks of new technologies; the potential shortage of qualified resources; and the impact on established business processes. Many organizations that subscribe to the “buy before build” principle were also evaluating MDM vendors and system integrators as potential technology partners. The survey also found that many MDM initiatives that may have started as small pilots and were developed in-house were rapidly growing in size and visibility and have been repositioned to use best-in-class commercially available solutions.

Three years later, at the beginning of 2010, when this second edition of the book was written, according to the new MDM Institute report,1 by 2012, 80 percent of Fortune 5000 companies will have committed to MDM as a core business strategy and have implemented at least one master entity solution (typically, a party or a product). From the comparison of the surveys performed in 2007 and 2010, it is fairly clear that MDM’s adoption increased significantly over these years. The MDM that first started within Fortune 2000 has moved downstream to include “smaller” large companies outside Fortune 2000 and has begun penetration into the mid-market. Many companies are looking to move from a single-domain MDM to a more comprehensive multi-domain MDM, to leverage an MDM solution to resolve and manage relationships and hierarchies, and to integrate MDM with unstructured information.

And this MDM growth trend is not just about moving from a single-domain MDM to a multi domain MDM. In this chapter, we’ll show that the most common drivers and challenges of MDM apply across many industry verticals and public sectors. In other words, we can see clearly now that MDM is indeed a horizontal discipline.

In the MDM space, the “buy before build” principle has evolved even more to a clear dominance of the “buy” over the “build.” MDM products have been quickly maturing and currently provide numerous advanced capabilities “out of the box.” These capabilities cannot typically be easily matched by homegrown solutions.

Although this “buy over build” trend is encouraging and points to an MDM market expansion, we need to recognize that embarking on an MDM journey is not a small or easy task. From a business perspective, building or buying an MDM solution is a significant undertaking that has to be supported by a comprehensive and compelling business case. Indeed, considering the high degree of technical and business risk, the significant software licenses and implementation costs, the (typically) long multiphase duration, and the high level of visibility and organizational commitment required to implement a full-fledged Master Data Management initiative, an MDM project should be considered if it can provide an enterprise with a well-defined and measurable set of benefits and a positive return on investment (ROI) in a reasonable amount of time. In short, a completed and deployed MDM solution should provide the enterprise with a tangible competitive advantage. Chapter 12 in Part IV of this book discusses the business case, the MDM roadmap, and its challenges in more detail. You can find more information using the references given at the end of this chapter.2,3,4,5

Every major IT industry analysis organization indicated that market demand for MDM remains healthy even during the economy downturn of 2009. As per Gartner Research,6,7 demand for MDM technology remains strong, with 93 percent of businesses sustaining or increasing MDM spending. MDM business case, vision, strategy, processes, governance, and technology remain the focus of the MDM community worldwide.

MDM Growth and Customer Centricity

One way for customer-facing enterprises to achieve a competitive advantage is to know their best and largest customers, and be able to organize them into groups based on explicit or implied relationships, including corporate and household hierarchies. Knowing customers and their relationships allows an enterprise to assess and manage customer lifetime value, increase effectiveness of marketing campaigns, improve customer service, and thus reduce attrition rates. It is also important to recognize “bad” customers, including relationships involved in fraudulent activities (or “spinners”). This term applies to former customers dropped due to a history of delinquencies and unpaid debts. Spinners attempt to open new accounts under another name or use other tricks to conceal their true identity. A customer, individual, or a company that receives a significant credit for an enterprise’s products or services by means of opening multiple accounts under different identities creates a significant credit risk for the enterprise, thus jeopardizing its financial stability.

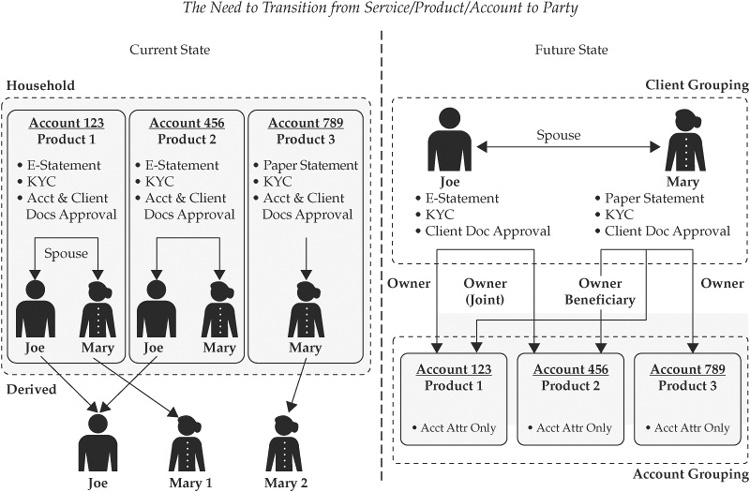

In the account-centric world, depicted on the left side of Figure 2-1, there is no systemic way to determine whether the Joe who holds an employment insurance account (Account 123) is the same Joe that signed the student loan (Account 456). Similarly, does the record for the Mary from the employment insurance account represent the same Mary who owns the pension plan account (Account 789)? In the traditional account-centric scenario, the government agency cannot see the total of benefits that a citizen and his household receive from the government. Using the government agency as an example, in the future world, presented on the right side of Figure 2-1, a new entity “Citizen” is resolved and maintained, which makes the agency “customer centric” (more accurately, “citizen centric” in this example). In the future state, the organization that implements MDM is enabled to support a holistic, panoramic view of a customer or a party, including relationships between people, relationships between people and accounts, and the roles citizens play on the accounts. We see similar needs in customer-centricity patterns across multiple industries: financial services, telecommunications, insurance, hospitality, and so on. This transformation, revolutionary from the business perspective, represents the Holy Grail of MDM for many organizations and promises significant competitive advantages.

Although it may appear that the same can be accomplished using a more traditional CRM system, a full-function customer-centric MDM solution can extend the scope of already familiar CRM sales-services-marketing channels by integrating additional information sources that may contain customer-related data, including back-office systems, finance and accounting departments, product master references, and supply-chain applications. This broad and far-reaching scope of MDM data coverage provides a number of opportunities for an MDM-empowered enterprise to achieve a sustainable competitive advantage. Let’s look at some prominent components of this competitive advantage.

FIGURE 2-1 Transformation from account-centric to customer-centric enterprise

Even though Figure 2-1 depicts a customer-centric transition for citizens or retail customers, organizations serving commercial or institutional customers can equally benefit from MDM and obtain considerable competitive advantage by enabling the organizations to address the following questions and problems:

• Value of a customer and product Does your organization measure the value of a client and product correctly by including all the subsidiaries, divisions, sites, brands, and so on? Do you classify/categorize your customers correctly and provide a value-based level of service?

• Marketing Are there up-selling or cross-selling opportunities that your organization is missing? If your organization has relationships with Company A and some of its subsidiaries, but is not aware of the existence of some other subsidiaries in the complex hierarchical structure of Company A, marketing opportunities may have been missed.

• Credit risk Does your organization correctly evaluate relationship risks? The knowledge that a midsize company is a subsidiary of a larger corporation is critical in evaluating the risk associated with the given relationship.

• Pricing and fees Do your commercial customers receive the right pricing and fees? Lack of understanding of B2B hierarchies can cause errors in pricing and fees, impact customer satisfaction, and result in considerable overhead.

• Data-cleansing efforts Does your organization spend money on data-cleansing efforts aimed at fixing your client and product hierarchy data? This problem can be permanently resolved by MDM

In Parts II and IV of this book, we will discuss specifics of an MDM architecture, its components, and the MDM roadmap as it applies to organizations serving individual customers and commercial enterprises.

Business and Operational Drivers of MDM

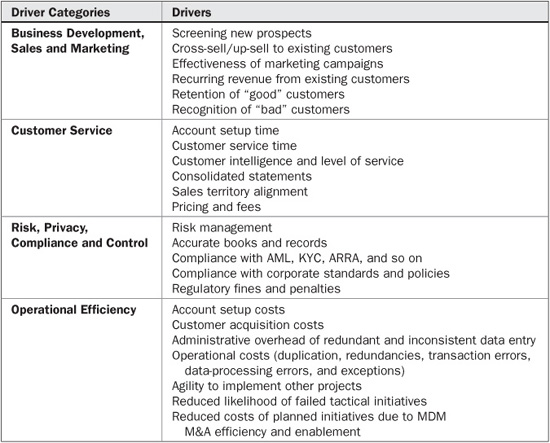

In order to define the value proposition and end-state vision, we have to clearly understand both business and operational drivers. Table 2-1 lists typical business drivers grouped by high-level categories such as Business Development, Sales and Marketing; Cost Reduction; Customer Service; and Compliance and Control. Organizations can use this list as a starting point to prioritize and quantify the importance of the business drivers as they apply to the company.

For more information, see “The Business Case for Master Data Management,”8 as well as “Creating a Business Case for Master Data Management.”9

TABLE 2-1 Common MDM Drivers

Once the drivers and the areas of impact are understood and documented, the project team in conjunction with the business stakeholders should perform an in-depth applications and business process analysis that answers the following questions:

• What business requirements drive the need to have access to better quality and more accurate and complete master data while still relying on existing processes and applications?

• What business activities would gain significant benefits from changing not just applications but also key business processes that deal with customer interactions and customer services at every touch point and across front- and back-office operations?

To illustrate these points, consider a retail bank that decides to develop an MDM platform to achieve several business goals, including better customer experience, better compliance posture, and reduced maintenance costs for the IT infrastructure. The bank may deploy an MDM Data Hub solution that enables the aggregation and integration of customer, product, and location data across various channels, application systems, and lines of business. As a result, existing and new applications may have access to a new customer master that should contain more accurate and complete customer information. The bank’s Customer Relationship Management (CRM) and various Business Intelligence (BI) systems may have to be modified to leverage this new data. Improved insights into complete customer profile and past behavior as well as better anticipation of the customer’s needs for products and services translate into better customer service and higher customer satisfaction. These are all valid and valuable benefits that allow the bank to quantify and measure a tangible return on investment. However, the core banking business still revolves around the notion of customer accounts, and the bank will continue to service its customers on the basis of their account type and status.

Moving to a customer-centric business model would allow the bank to understand and manage not just customer accounts but the totality of all current and potential customer relationships with the bank, to drastically improve the effectiveness and efficiency of customer interactions with the bank, and even to improve the productivity of the bank’s service personnel. To achieve these goals, the bank would have to not only create a new customer master, but also redesign and deploy new, more effective and efficient business processes. For example, in the past the bank may have had an account-opening application that was used to open new customer accounts and modify existing ones. In the new customer-centric world, the bank may have to change its business processes and operational workflows in order to “create a customer” and modify his or her profile, assets, or relationships (accounts). These new processes will be operating in the context of the integrated holistic customer view. The efficiencies may come from the fact that if the bank deals with the existing customer, it can effectively leverage information already collected about that customer. The bank can leverage this information to shorten the time required to perform the transaction, and to offer better, more personalized, and more compelling products and/or services that are configured and priced based on the total view of the customer. Clearly, these new processes are beneficial to the customer and the bank, but they may represent a significant change in the behavior of the bank’s application systems and customer service personnel. This is where the customer-centric impact analysis should indicate not only what processes and applications need to change, but what would be the financial impact of the change, and what would be the expected cost-benefit ratio if these changes are implemented as part of the MDM initiative.

Improving Customer Experience

Customer experience has emerged as a clear competitive differentiator. In the Internet-enabled e-business world, customer experience is viewed as one of the key factors that can strengthen or destroy trusted relationships that a customer may have with the enterprise. Customer experience includes a variety of tangible and intangible factors that collectively can make a customer a willing and eager participant or a dissatisfied party looking to take his or her business to a competitor as soon as possible. And in the era of e-banking, e-sales, and other Internet-enabled businesses, customers can terminate their relationship with the enterprise literally at a click of a button.

As a master customer data facility that manages all available information about the customer, MDM enables an enterprise to recognize a customer at any “point of entry” into the enterprise and to provide an appropriate level of customer service and personalized treatment—some of the factors improving customer experience and increasing enterprise’s brand “stickiness.” Let’s illustrate this point with an example of a financial services company.

This company has created a wealth management business unit that deals with affluent customers, each of whom gets services from a dedicated personal financial advisor (PFA). When such an affluent customer calls his or her financial advisor, it is extremely important for the advisor to be able to access all the required information promptly, should it be information about a new product or service, a question about investment options, or a concern about tax consequences of a particular transaction. Unfortunately, in many cases, lack of customer data integration does not allow companies to provide an adequate level of service.

For example, it is customary in wealth management to have a variable-fee structure, with the amount of service fees inversely proportional to the amount of money under management (in other words, it is not unusual to waive fees for a customer who has total balances across all accounts that exceed a certain company-defined threshold). Of course, such a service would work much more effectively if the enterprise can readily and accurately recognize a customer not as an individual account holder but as an entity that owns all her or his accounts. What if a high-net-worth client calls because his fees were calculated incorrectly? The advisor could not obtain the necessary information during the call, and thus would not be able to provide an explanation to the customer and would ask for extra time and possibly an additional phone call to discuss the results of the investigation. This is likely to upset the customer who, as an affluent individual, has become used to quick and effective service. This situation can deteriorate rapidly if, for example, the investigation shows that the fee system interpreted the customer’s accounts as belonging to multiple individuals. The corrective action may take some time, several transactions, and, in extreme cases, a number of management approvals, all of which can extend the time required to fix the problem, and thus make the customer even more unhappy.

This is a typical symptom indicating that a sound customer-centric MDM solution is required. If the situation is not resolved and occurs frequently, this may weaken the customer’s relationship with the organization and eventually cause increased attrition rates.

Improving Customer Retention and Reducing Attrition Rates

To achieve sustainable growth, a company needs to focus on the customer segments with the highest growth potential in the area in which the company specializes—and build high loyalty by helping customers to realize their expectations from products and services offered by the company. Conceptually, these segments can be classified as follows:

• New, high-revenue-potential customers

• Existing customers whose total revenue potential has not yet been realized

In the case of new customer segments, every customer-facing enterprise has to solve the challenge of finding and acquiring new customers at the lowest possible acquisition cost. However, whether it is a new or an existing customer, enterprises have to find ways to improve customer retention rates at even lower costs. This last point is very important: Experience and market studies show that the cost of new customer acquisition could be many times the cost of retaining the existing customer, so the enterprise needs to understand the reasons that cause an existing customer to leave and go to a competitor. As mentioned in the preceding section, among the reasons for attrition are cumbersome or inconvenient ways of doing business (for example, an inefficient or aesthetically unappealing web portal, few retail bank branches, inconvenient locations or working hours, and a large number of high or “unfair” fees), poor customer service, lack of personalized or specific product and services offerings, lack of trust caused by violation of the customer’s privacy and confidentiality, overly aggressive sales and marketing, and other factors that individually or collectively comprise the customer experience.

The cause of many of these factors is the lack of accurate business intelligence about the customer. Business intelligence has always been a valuable competitive differentiator, and best-in-class BI solutions such as customer analytics and customer data mining are critical to achieve a competitive advantage. The accuracy of business intelligence, in turn, depends on the availability, quality, and completeness of customer information. The value of accurate business intelligence became even more important as the result of the global financial crisis of 2008–2009, where the number of retail and commercial customers defaulting on their financial obligations (loans, mortgages, and so on) increased dramatically, and directly impacted the bottom line of any business that had an exposure to this risk. Thus, the role of an MDM solution designed to acquire and deliver complete, timely, and accurate customer information to appropriate users and BI applications has become ever more important.

Growing Revenue by Leveraging Customer Relationships

Enterprises have come to realize that customer loyalty is eroding, and with shortening product life cycles, most markets are facing intense competition and commoditization. In addition, and especially in financial services, the institutions have made a significant effort to acquire what is known as the “most profitable customers.” However, because the total population of “best customers” is finite (that is, there are only so many customers that are worth doing business with), the businesses have realized that the new sources of revenue may come not from new customers but from the ability to understand and leverage the totality of the relationships a given customer may have with the enterprise. Therefore, the companies have to manage the life cycle of their customers beyond the acquisition. To state it differently, the strategy involves the notion of acquiring, understanding, and servicing the customer in the context of his or her relationships with the enterprise. This is different from the commonly used segmentation approach of CRM systems, which is based primarily on the history of customer transactions.

Understanding and leveraging relationships is one of the ways MDM can help to grow the business through increasing the “share of the wallet,” by extending additional services to the existing customers individually and as part of various customer groups. This goal can be accomplished if the enterprise has developed and maintains accurate, complete, and actionable customer intelligence—a set of analytical insights and predictive traits indicating the best customers and the types of services and products that need to be offered to them in order to gain an increased share of the wallet. This customer intelligence is especially effective if it is gathered in the context of customer relationships with the enterprise and other customers. Examples of a relationship include a household, family, business partners, or any other group of customers that can be viewed as a single group from the service perspective. This relationship-based intelligence allows the enterprise to interact with customers based not only on their requirements and propensity to buy products and services, but also on the added opportunity of leveraging customer relationships for increased revenue as a percent of the entire relationship group’s share of the wallet. The importance of understanding the relationships applies equally well to the corporate customers and partners that the company works with in the normal course of business. In the case of corporate customers, the relationships tend to be bi-directional (that is, the company offers products and services to a customer and buys that customer’s products and services for its own use), thus creating an important management metric often called “balance of trade.”

In addition to the increased “share of the wallet” and better value of the “balance of trade,” an MDM solution can help to grow the customer base by identifying opportunities for acquiring new customers through actionable referrals. These MDM-enabled revenue growth opportunities drive market demand for MDM data integration products and services.

Improving Customer Service Time: Just-in-Time Information Availability

As mentioned in Chapter 1, one of the drivers behind Master Data Management is the need to make accurate data available to the users and applications more quickly. In many cases, the latency of information has a significant negative impact on various business processes, service quality and delivery, and customer experience. Indeed, imagine a customer contacting a service center with a question or complaint only to hear that the customer service representative cannot get to the right information because “our system is slow” or “this information is in our marketing systems and we don’t have access to it.” Likewise, a trading partner may contact the company’s representative complaining about an unauthorized or invalid transaction, without getting a timely and satisfactory answer to the query. These situations do not improve the customer’s or partner’s confidence in the way the enterprise manages its business.

Timely availability of accurate data is clearly a requirement for any enterprise, especially customer-facing businesses that support a variety of online channels. This data availability and timeliness has two key components:

• Physical, near-real-time access to data is a function of operating systems, applications, and databases. Practically every organization has deployed these systems and the underlying technical infrastructures to enable the near-real-time execution of online transactions.

• Accurate and timely data content is created by aggregating and integrating relevant information from a variety of data sources, and this integration is the job for an MDM solution.

The latter point is one of the reasons enterprises seriously consider significant investment into MDM initiatives. Having just-in-time, accurate, and complete master data can not only improve customer service, but can also enable the enterprise to create near-real-time cross-sell and up-sell opportunities across various online channels. Successful cross-sell and up-sell activities have a significant positive impact on cost of sales and result in increased sales revenue. Likewise, just-in-time, accurate, and complete information about transactions, products, accounts, and customers is key to fraud detection, risk management, compliance requirements for unauthorized access, customer onboarding, and a host of other key business activities.

The typical overnight batch-cycle data latency provided by traditional data warehouses is no longer sufficient to support some business demands. Enterprises are looking for ways to cross-sell or up-sell immediately when a customer is still in the store or shopping online on the company’s website. Today, sophisticated customer analytics and fraud detection systems can recognize a fraudulent transaction as it occurs. MDM-enabled data integration allows an enterprise to build sophisticated behavior models that provide real-time recommendations or interactive scripts that a salesperson could use to entice the customer to buy additional products or services.

For instance, suppose you have just relocated and purchased a new home. You need to buy a number of goods. The store should be able to recognize you as a new customer in the area and impress you with a prompt offering of the right products that fit your family’s needs. In order to do this efficiently, an MDM system would find and integrate your customer profile, household information, and buying patterns into one holistic customer view.

Using this integrated data approach, an advanced sales management system would be able to recognize an individual as a high-potential-value customer regardless of the channel the customer is using at any given time.

Improving Marketing Effectiveness

Marketing organizations develop MDM solutions to improve the effectiveness of their marketing campaigns and enable up-sell and cross-sell activities across the lines of business. It is not unusual for an MDM solution to increase the effectiveness of marketing campaigns by an order of magnitude. According to Michael Lowenstein,10 the Royal Bank of Scotland reduced the number of marketing mailings from 300,000 to 20,000 by making marketing campaigns more intelligent, targeted, and event driven.

At a high level, marketing campaigns are similar across industries. There are some industry-specific marketing areas, though (for example, Communities of Practice). This marketing solution is well known in the pharmaceutical industry. The Communities of Practice solution is based on a methodology aimed at identifying medical professionals considered to be “thought leaders” by their professional communities within a given geography and specialization area (specific infectious diseases, certain inflammatory diseases, areas of oncology, and so on). As soon as the thought leaders are identified, the pharmaceutical company can launch a highly selective marketing campaign targeting the thought leaders who are expected to influence their colleagues on the merits of the drug or product. One of the key challenges in implementing the Communities of Practice approach is to recognize medical professionals and maintain the required profile information and information about their professional relationships and organizations. For more information, refer the article by to Etienne Wenger, et al.11

Reducing Administrative Process Costs and Inefficiencies

A significant MDM driver is its ability to help reduce the administrative time spent on account administration, maintenance, and processing. It is not unusual that every time a new account for an existing customer needs to be opened, the customer profile information is entered redundantly again and again. Many current processes do not support the reuse of the data that has already been entered into the account profile opened at a different time or by a different line of business. One of the reasons for not reusing the data is the complexity associated with finding a customer’s other account or profile data across various application silos.

An MDM solution capable of maintaining the client profile and relationships information centrally can significantly reduce the overhead of account opening and maintenance.

In addition, a comprehensive MDM solution can help to improve data quality and reduce the probability of errors in books and records of the firm. This improved accuracy not only helps maintain a high level of customer satisfaction but also enables an enterprise to be in a better position to comply with the requirements of government and industry regulations, such as the Sarbanes-Oxley Act for the verifiable accuracy and integrity of financial reporting. Some financial service organizations invest in MDM with the goal of reducing the administration time spent by the sales force by 50 percent.

Reducing Information Technology Maintenance Costs

In addition to the business drivers described in the preceding section, enterprise-wide MDM initiatives focused on the creation of a new, authoritative, complete, and accurate source of master data records are often driven by the objective to reduce the cost of ongoing maintenance of the IT infrastructure, applications, and operations. Lack of common system architecture, lack of systemic controls, and data inconsistencies cause data-processing errors and increase the cost of IT maintenance and operations. In addition, from the information technology perspective, the absence of a holistic authoritative system of record results in the limited ability of the enterprise to adapt to the ever-changing business requirements and processes, such as those driven by new and emerging regulatory and compliance demands. The need for system and application agility to support business and regulatory demands is a powerful MDM driver. Properly implemented MDM solutions enable more agile application development and reduce system implementation costs and risks. Many enterprise-wide initiatives, such as CRM and Enterprise Data Warehouse, often fail because in the pre-MDM days the issues of data accuracy, timeliness, and completeness had not been resolved proactively or, in some cases, successfully.

MDM Challenges

This section offers a high-level view of the challenges and risks that a company faces on its way toward mature Master Data Management and customer centricity. Parts II, III, and IV of this book will deal with these issues in more depth.

We start by offering two perspectives that organizations should acknowledge and address in adopting and executing a successful MDM strategy:

• The first perspective addresses business issues, such as defining a compelling value proposition that encompasses a cross-functional perspective championed by data governance and sound data policies, project drivers, the new end-state business vision, the project organization, competing stakeholder interests, and overcoming socialization obstacles.

• The second perspective addresses technical issues such as architecture, data profiling and quality, data synchronization, visibility, and security. In addition, it examines regulatory and compliance project drivers.

One of the general observations we can make by analyzing how MDM solutions are implemented across various industries is the strong desire on the part of the enterprise to embark on an MDM initiative in a way that properly addresses MDM challenges, manages and mitigates implementation risk, while at the same time realizing tangible business benefits. In practical terms, it often means that MDM initiatives start small and focus on a single high-priority objective such as improving data quality or creating a unified customer profile or product hierarchies based on available data. Often, these initial MDM implementations are done using in-house development rather than a vendor MDM tool, and they try to leverage existing legacy systems to the extent possible. For example, many organizations try to reuse existing business intelligence, reporting, and profile management applications while providing them with better, more accurate, and more complete data.

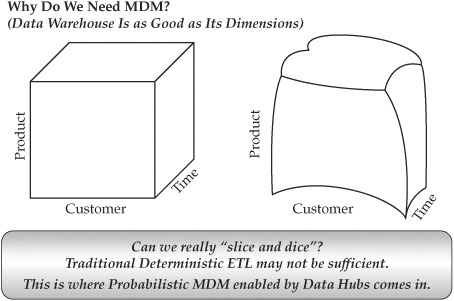

Many MDM implementations start with the primary focus of enabling data warehousing by building the content of data warehousing dimensions, oftentimes referred to as “analytical MDM.” Indeed, for complex data warehousing dimensions such as Customer, Product, Service, Provider, and Location, traditional ETL technologies may not be able to create and maintain high-quality dimensions. As a result of this problem, the main data warehousing promise of enabling an enterprise with “slice and dice” reporting and analytics capabilities to calculate the total value of a relationships, and other customer- and product-centric metrics, remains unrealized. The paradigm of “slice and dice” heavily relies on the perfection of multidimensional data structures containing all possible levels of measures. These structures are often referred to as “multidimensional cubes” or simply “cubes.” In reality, the cubes may be far from perfection, as illustrated on the right side of Figure 2-2.

In the case of Customer dimensions, for example, required “slice and dice” capabilities can provide correct results only if all expected customers and nodes of the corporate hierarchy are accounted for and no double-counting is performed.

FIGURE 2-2 “Slice and dice” capabilities depend on the quality of complex dimensions.

As the initial pilots begin to prove their usefulness to the business community, we see a common trend of expanding the scope of the project by including additional data sources and new consuming applications. This may include functionality that can leverage new customer identity information and create new service improvement and revenue opportunities driven by more complete knowledge of the customers and their relationships. Ultimately, MDM initiatives mature enough to have a profound impact on the business model of the enterprise by enabling enterprise transformation from account-centric to customer-centric processes.

From the technology point of view, we see that after projects that were initially developed in-house succeed in implementing an MDM proof of concept, enterprises start evaluating and implementing best-in-class vendor solutions. Many enterprises ensure that this transition is relatively smooth by adapting a service-oriented architecture (SOA) approach and proven MDM architecture patterns, even to the in-house MDM pilot implementations. In fact, we see that those enterprises that follow the SOA approach can relatively easily grow their MDM framework by replacing MDM components that were developed in-house with longer-term SOA-based MDM vendor products combined with the enterprise-wide SOA infrastructures, common messaging frameworks, common process management, and even common enterprise-wide information security.

To summarize, some common high-level MDM approaches include implementation strategies aimed at reducing project and investment risk, and a broad adoption of the service-oriented architecture to build, integrate, and deploy an MDM Data Hub as a component of the overall enterprise architecture.

On the business side, enterprises are beginning to see significant benefits that MDM solutions offer, including growth of revenue and up-sell and cross-sell opportunities, improved customer service, consistent cross-channel customer experience, increased customer-retention rates, better visibility into key performance indicators for business relationship and partner management, and a better regulatory and compliance posture for the enterprise. At the same time, enterprises quickly realize the complexity and multidisciplinary nature of an MDM initiative and therefore often treat an MDM program as a multiphase corporate initiative that requires large cross-functional teams, multiple work streams, robust and active project management, and a clearly defined set of strategic measurable goals.

The following list presents some of the key technical challenges facing every organization that plans to implement MDM:

• Technical aspects of data governance and the ability to measure and resolve data quality issues.

• The need to create and maintain enterprise-wide semantically consistent data definitions.

• The need to create and maintain an active and accurate metadata repository that contains all relevant information about data semantics, location, and lineage.

• Support and management of distributed and/or federated master data, especially as it requires business rules–driven synchronization and reconciliation of data changes across various data stores and applications.

• Uniformed architecture approach of integrating, federating, and distributing master data, especially reference data, in a way that does not proliferate methods and techniques that result in creating redundant data.

• The complexity of the processes required to orchestrate composite business transactions that span systems and applications, not only within the enterprise but also across the system domains of its business partners.

• Scalability challenges that require an MDM solution to scale with data volumes, especially as new entity-identification tokens such as radio frequency identification (RFID) solutions for products, universal identification cards for citizens, and GPS coordinates for locations become available.

• Scalability of data types. The need to rationalize and integrate both structured and unstructured content is rapidly becoming a key business requirement, not only in the areas of product, trading, and reference data, but even when dealing with customer information, some of which can be found in unstructured files such as documents and images, as in a photo gallery.

• The need to implement process controls to support audit and compliance reporting.

• The challenges of leveraging an existing enterprise security framework to protect the new MDM platform and to enable function-level and data-level access control to master data that is based on authenticated credentials and policy-driven entitlements.

Senior Management Commitment and Value Proposition

Enterprise-scale MDM implementations tend to be lengthy, expensive, complex, and laden with risks. A typical MDM initiative takes at least a year to deliver, and the initiative’s cost can easily reach several million U.S. dollars. Senior management’s real commitment in terms of strategy, governance, and resources is essential for the success of the initiative. Only a compelling value proposition with clearly defined challenges and risks can secure their commitment.

On the surface, defining and socializing a compelling value proposition appears to be a straightforward task. In practice, however, given the diversity of project stakeholders and new concepts that an MDM project often brings to the table, this step will likely take time and energy and may require multiple iterations. Projects may have to overcome a few false starts until finally the organization gains the critical mass of knowledge about what needs to be achieved in all key domains. Only then can the project team obtain and confirm required levels of executive sponsorship, management commitment, and ownership.

Customer Centricity and a 360-Degree View of a Customer

The stakeholders often use popular terms such as “360-degree view of a customer,” “single version of the truth,” “golden customer record,” and so on. We used this terminology in Chapter 1 as well. It takes time for the organization to understand what these frequently used terms mean for the company and its business. For one thing, these terms by themselves do not necessarily imply customer centricity. Indeed, many CRM systems had a holistic customer view as one of their design and implementation goals, but achieving this 360-degree customer view without changing fundamental business processes did not transform an organization into a customer-centric enterprise, and the traditional account-centric approach continued to be the predominant business model. One way to embark on the road to becoming a customer-centric enterprise is to clearly articulate the reasons for the transformation. To accomplish that goal, the project’s stakeholders should answer a number of questions:

• What business processes currently suffer from a lack of customer centricity?

• Do different lines of business or business functions, such as compliance, marketing, and statement processing, have identical definitions of a customer, including cases that deal with an institutional customer?

• Can the company share customer information globally and still comply with appropriate global and local regulatory requirements?

• What are the benefits of the new customer-centric business processes and how can the company quantify these benefits in terms of ROI?

Answering these questions may not be as simple as it sometimes appears, and often represents a challenge for an organization embarking on an MDM project. Indeed, many of these questions, if answered correctly, imply a significant financial, resource, and time commitment, so they should not be taken lightly. On the other hand, not answering these questions early in the project life cycle may result in a significant risk to the project when the stakeholders begin to review the project status, goals, budget, and milestones.

Challenges of Selling MDM Inside the Enterprise

By their very nature, MDM projects enable profound and far-reaching changes in the way business processes are defined and implemented. At the same time, experience shows that enterprise-scale MDM initiatives tend to take a long time and significant expenditure to implement. These factors make the challenges of socializing the need and benefits of MDM ever more difficult.

Because MDM initiatives are often considered to be infrastructure projects, the articulation of business benefits and compelling value proposition represents an interesting management challenge that requires considerable salesmanship abilities and a clear and concise business case. Without any application that can rapidly take advantage of a new MDM environment, and without clearly articulated, provable, and tangible ROI, it could be difficult to sell the concept of the MDM (and justify the funding request) to your senior management and business partners. In fact, selling the idea of a new application that can quickly take advantage of the MDM solution could prove to be the most effective way to define a compelling value proposition. This consumption-based approach often becomes a preferred vehicle for getting the buy-in from the internal stakeholders, especially if the new application delivers certain mandated, regulatory functionality.

In some cases, MDM initiatives start as IT process improvement/new system platform projects (moving from a mainframe to an open-system platform, moving from one database management system to another, and so on). In these situations, the projects may not have a clearly articulated set of business requirements, and the primary justification is based on the enterprise technology strategy direction, cost avoidance, partner integration requirements, or the objectives of improving the internal infrastructure, rationalizing the application portfolio, improving data quality, and increasing processing capacity and throughput. If these drivers are sufficiently important to the enterprise, the organization responsible for the delivery of the new capabilities becomes a vocal and powerful champion, and the MDM project can start without too much resistance.

Whether there are clear and compelling business requirements, or the MDM tasks and deliverables are defined within a more traditional technology-driven project, one thing is clear: Large, complex, and costly initiatives such as MDM projects typically fail without comprehensive buy-in from senior management and other stakeholders. We will discuss this in more detail in Chapter 12.

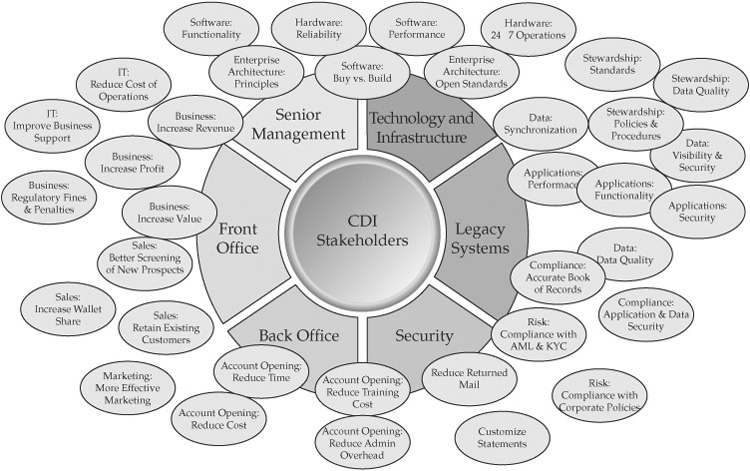

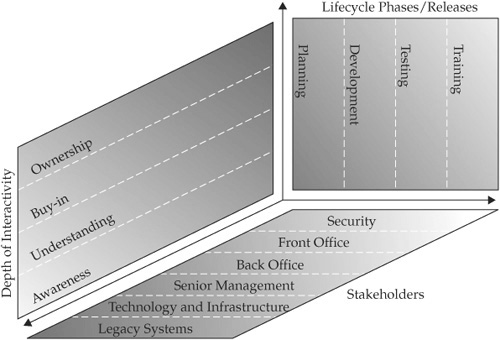

It is important to point out that the answers to the questions for the stakeholders that are listed in the previous section are expected to be multifaceted and would depend on the context and the stakeholder role. Indeed, initiatives and projects of MDM caliber involve multiple stakeholder groups (see Figure 2-3 for a graphical representation of the stakeholder groups).

This stakeholder landscape includes executive management and sponsors; line-of-business leaders; front, middle, and back office; corporate and LOB data governance professionals; technology managers, architects, and engineers; finance; regulatory compliance; legal department; information security; technical infrastructure; external technology partners; and possibly other participants. Given their diversity and differences in priorities and goals, these stakeholders will most likely have different opinions and will thus provide different answers to the questions listed earlier. It is crucial to the success of the project that even though the views are different, they must represent different sides of a single consistent “story” about the project’s goals, objectives, strategy, priorities, and the end-state vision. It is the ultimate challenge of the project’s executive sponsors and project management team to establish, formulate, and disseminate project messages consistently to the appropriate team members, stakeholders, and project sponsors.

FIGURE 2-3 Variety of stakeholders and functional areas of MDM

From the risk management perspective, human factors outweigh technical factors. For example, the IT organization might decide to implement the MDM project without obtaining an organizational buy-in. Even if the resulting solution is technically sound and perfectly implemented, the efforts would be viewed as a failure if the project is not socialized properly within the organization. Only about 20 percent of all MDM failures are caused by poor technology or architecture decisions. An estimated 80 percent have a root cause in political, management, user acceptance, and other human and cultural issues. In order to mitigate this risk, the initiative should be aligned with business objectives. In this case, project sponsors can “sell” the effort as a major improvement in business processes, customer experience, customer intelligence, business development, marketing, compliance, and so on.

Socializing MDM as a Multidimensional Challenge

The socialization challenge of a large-scale initiative like MDM is a multidimensional problem (see Figure 2-4).

We see the socialization problem as having at least three dimensions. The first dimension illustrates a variety of stakeholder groups.

The phases of the project life cycle are shown as the second dimension. The role of each group evolves over time as the initiative progresses through the life-cycle phases. For example, business analysts who represent various business units and define business requirements at the beginning of the initiative may later participate in business acceptance testing. The challenges continue in the roadmap development and architecture phase when the solution is defined and the road to the end state is determined. The challenges vary as the project evolves, but they continue to be present throughout the project life cycle. To ensure the success of the MDM initiative, the project team has to make sure to obtain and regularly renew the organizational commitment from multiple stakeholder groups throughout all phases of development, implementation, deployment, and training.

FIGURE 2-4 The three-dimensional socialization problem

The third dimension represents the depth of interactivity or the level of user buy-in and involvement. The user involvement begins with awareness. At this level, a stakeholder group becomes aware of the upcoming change but may have a limited high-level understanding of the initiative. The next level includes understanding the magnitude and complexity of the effort and its primary implications. Finally, the key stakeholders should participate in the initiative at the ownership level. These stakeholders actively participate in the effort and are responsible for assigned deliverables. On some projects the level of interaction between stakeholders is insufficient, and oftentimes stakeholders are taken by unpleasant surprise when they eventually learn about some decisions made without their involvement. On the other hand, having numerous standing meetings attended by 50–70 people, due to an attempt to engage all parties in MDM project discussions, is counterproductive. Proper understanding of the depth of interactivity helps in building and maintaining a balanced project communications plan.

Technical Challenges of MDM

MDM projects represent a myriad of technical challenges and risks to IT managers, systems, applications and data architects, security officers, data governance officers, data stewards, and operations. This section focuses on high-level implementation challenges and risks.

For example, customer-centricity solutions are trivialized by suggesting that the problem can be solved by placing all customer data in a single repository. This approach has been known not to work in all cases. Similarly, the best way to build a product master may not lie in making a central product database for all product information as a single data repository. In reality, this approach is limited and may be appropriate for small department-level projects. However, MDM projects become much more complex and difficult as the size of the company and the diversity of customer, product, service, and location data grows. In midsize and large organizations, it is not unusual to find that master data is physically distributed and logically federated across multiple application systems that provide existing and new business functions and support various lines of business. Rationalizing, federating, and aggregating this information is not a trivial task, and dealing with the legacy data and applications brings additional complications into the mix. This is especially true if you consider that in many cases legacy systems lack complete and accurate process documentation and stable data definitions—the principal obstacles to seamless semantic integration of heterogeneous data sources.

Of course, an enterprise may adopt a strategy of decommissioning some legacy systems to help deal with this challenge, and can put together an end-state vision for the MDM project that allows for some of these legacy application systems to be phased out over time. However, this strategy can be successful only if the candidate legacy systems are carefully analyzed for the potential impact on remaining upstream and downstream application systems. In addition to the impact of decommissioning, a careful analysis needs to take place to see the impact of introducing an MDM platform into the existing application environment, even if decommissioning is not going to take place. The project team should develop an integrated project plan that contains multiple parallel work streams, clearly defined dependencies, and carefully allocated resources. The plan should help to direct the implementation of an MDM platform in a way that supports coexistence between the old (legacy) and the new (MDM) environments, until such time as the organization can decommission the legacy applications without invalidating business processes. We discuss these and other implementation challenges in Part IV of the book.

Most of the technical MDM challenges to achieving consistent master data quality deal with the following:

• Implementation costs and time-to-market

• Data governance

• Data quality, synchronization, integration, and federation

• Data visibility, security, and regulatory compliance

The sections below provide additional details on some of these challenges. We’ll discuss the challenges of data governance in more detail in Chapter 17.

Implementation Costs and Time-to-Market Concerns

As we have already stated, large-scale MDM projects are risky. The risk is even higher because these projects are supposed to result in significant changes in business processes and impact structural, architectural, and operational models. Achieving all stated objectives of an MDM project may take several iterations that can span years. Therefore, it is not realistic to assume that the project team can deliver a comprehensive end-to-end solution in a single release. Such an unreasonable expectation would represent a significant implementation risk.

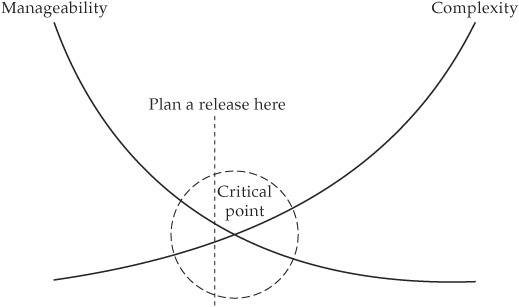

The project team can mitigate this risk by devising a sound release strategy. The strategy should include the end-state vision and an implementation plan that defines a stepwise approach in which each step or phase should deliver clear tactical benefits. These benefits should be tangible, measurable, and aligned with the strategic roadmap and business demands. Project plans should ensure that each release provides a measurable incremental business value on a regular, frequent basis, preferably every six to nine months. When multiple lines of business are involved in the MDM initiative, the first production release should be defined as a trade-off between the business priority of a given line of business and implementation feasibility that minimizes the delivery risk of the first release. We can extend this model by devising a strategy that maintains a trade-off between the business value of the release and the release manageability, risk, and complexity, as illustrated in Figure 2-5.

Another implementation risk of an MDM project is caused by a project plan or approach that does not take into account the issues related to existing legacy data stores and applications. For example, consider an MDM project with the goal of delivering a brand-new Data Hub.

FIGURE 2-5 Trade-off between release complexity and manageability

If the project plan does not account for the need to either integrate with or phase out the existing application legacy systems, the resulting MDM Data Hub environment may have questionable value because it will be difficult to synchronize it with various legacy systems and use it as an accurate authoritative master. In the case of MDM for Customer Domain, the challenge of concurrently supporting the new customer-centric universe and the old account-centric “legacy world” may be unavoidable. Both universes must coexist and cooperate in delivering business value, but the risks associated with this approach have to be understood and mitigated through careful planning. For instance, the coexistence and cooperation approach may require significant integration and synchronization efforts, may complicate application and data maintenance, and thus may increase operational risk. Not planning for these efforts may result in a highly visible project failure and could negatively affect the enterprise’s ability to transform itself into a new customer-centric business model and develop a sound MDM solution.

Another concern related to the drive toward customer centricity is its potential organizational impact due to the implementation of new system platforms and new business processes. As we show in Part IV of this book, major MDM implementations lead to significant changes in the business processes that can greatly impact stakeholders’ responsibilities and required skills. Some jobs can be significantly redefined. For example, a legacy mainframe application that was the system of record for customer information may lose its significance or may even be decommissioned when the MDM Data Hub becomes available as the new system of record for master data.

Partnerships with Vendors

Given the complexity of many MDM projects, it is reasonable to assume that no single vendor can provide an all-in-one, out-of-the-box comprehensive MDM solution that fits the business and technical requirements of every enterprise. This should not be looked upon as a limitation of continuously evolving vendor products but rather as another call for the acceptance of a service-oriented architecture philosophy. Conceptually speaking, each vendor provides a service or a combination of services used by an enterprise within its service-oriented infrastructure. This approach is aligned with a vision of an agile enterprise architecture optimized for an evolutionary change. As we know, reliance on a single product that fits all demands or a vendor that serves all enterprise needs leads to monolithic inflexible solutions that cannot evolve to support the changing business needs and open-architecture standards.

This puts MDM implementers in a position where they have to look for a combination of vendor products and home-grown solutions in order to meet the business demands of the enterprise. Involving multiple vendors is not unusual for any major MDM implementation. This approach requires that the organization implement a formal process of product evaluation and selection to determine which best-in-class products can make a short list of potentially acceptable solutions. Typically, once the short list is finalized, the organization may start a proof-of-concept activity where one or more vendors would implement working prototypes that demonstrate both functional and nonfunctional capabilities. Although this approach can protect the enterprise from blindly choosing a product based solely on the vendor’s claims, it does create significant management overhead due to running one or more proof-of-concept projects, managing additional resources, dealing with the shortage of skilled resources, and balancing conflicting priorities. Strong architectural and data governance oversight for the activities that include multiple vendors and implementation partners is a must, and the lack of such oversight represents a very common and significant implementation risk.

Data Quality, Data Synchronization, and Integration Challenges

Generally speaking, data has a tendency to “decay” and become stale with time as changes in business and technology occur on a regular or sporadic basis (products change names, financial systems change accounting rules, and so on). This is especially true for customer data. Indeed, a 2003 study completed by The Data Warehousing Institute titled “Data Quality and the Bottom Line” stated the following: “The problem with data is that its quality quickly degenerates over time. Experts say 2 percent of records in a customer file become obsolete in one month because customers die, divorce, marry, and move.”

To put this statistic into perspective, assume that a company has 500,000 customers and prospects. If 2 percent of these records become obsolete in one month, that would be 10,000 records per month, or 120,000 records every year. So, in two years, about half of all records are obsolete if left unchecked.

Master Data Management solutions can create and maintain consistent, accurate, and complete customer views, product hierarchies, reference records, and locations. Critical business decisions such as promotions, price changes and discounts, marketing campaigns, credit decisions, and daily operations revolve around key market, customer, and product data. Without an accurate and complete view of the master entities, efforts to provide targeted, personalized, and compelling products and services may prove to be ineffective.

In no small measure, a company’s success or failure is based on the quality of its master data. The challenge of MDM is to be able to quickly and accurately capture, standardize, and consolidate the immense amount of data that comes from a variety of channels, touch points, and application systems.

Many organizations have separate sales, operations, support, and marketing groups. If these groups have different databases of master data—and different methods for recording and archiving this information—it is extremely difficult for the enterprise to rationalize and understand all of the key business processes and data infrastructure issues simultaneously.

The crux of the problem most companies face is the inability to compile complete master entity views when most of the systems are isolated from each other in their stovepipes and operate independently. By definition, an MDM system effectively bridges the gap between various master data views by rationalizing, integrating, and aggregating master data collected from disparate data sources and applications in order to provide a single, properly resolved, accurate, consolidated view of the master data.

MDM solutions benefit the enterprise by pulling critical master information from existing internal and external data sources and validating that the data is correct and meets the business needs and data-quality standards of the enterprise. Over time, MDM solutions can further enrich master data with additional internal and external information, as well as store, manage, and maintain the master data as a benchmark for enterprise use.

One approach for maintaining data quality and integrity would be to tackle the problem at the operating system level. This seems to be a practical approach. After all, operating systems support applications that manage and execute transactions and maintain transactional properties of atomicity, consistency, isolation, and durability (ACID). To sustain these properties, operational, transactional applications tend to be isolated from nonoperational applications such as data warehousing and business intelligence systems. This “isolation” helps discover and resolve data-integrity issues one system at a time.

Correcting data quality in each of the operational systems is only part of the problem that does not address the MDM cross-system issues holistically. Once the data in a single system has been corrected, the data changes have to be synchronized and integrated with various data sources. Moreover, various data records about the same individual or product need to be aggregated into a single master database, often logically, creating a federated data store. Although data-integration challenges are not new and are not unique to the MDM space, Master Data Management emphasizes their criticality. The challenges of data integration include the following:

• Lack of standardization of customer or company names and addresses If this information isn’t standardized, it is difficult to resolve customer lifetime value, because customers may have different representations within the various application databases.

• No common identifier or linking of customers across systems For example, an individual customer record may be stored in several operational systems, and thus the customer can be represented differently in every system, even using different names and aliases. This representation mismatch may prevent an MDM solution from recognizing the same individual across various applications and data stores.

• Anonymous data Master data solutions often use special codes to signify anonymous or default data. For example, a phone number of “999-999-9999” or a birth date of “01/01/01” may represent common shortcuts for unspecified or missing data. These special codes may have to be treated in a way that escalates data content questions to the appropriate data steward.

• Stale, outdated data As we stated earlier, data has a tendency to change over time. Left unchecked and unmanaged, these changes do not get reflected in the master database, thus significantly reducing the value of data.

One of the stated goals and key requirements of any MDM solution is to create and maintain the best possible information about the master data regardless of the number and type of source data systems. To achieve this goal, Master Data Management should support an effective data-acquisition process (discussed in more detail in Chapter 5). The MDM process requires different steps and rules for different data sources. However, the basic process is consistent and at a minimum should answer the following questions:

• What points of data collection might have master data?

• What systems are impacted by master data and what master data is used by each of the affected systems?

• How does each data source store, validate, and audit master data?

• What sources contain the best master data for a given domain, entity, and possibly attribute?

• How can data be integrated across various data sources?

• What master data entities and attributes are required for current and future business processes?

Of course, there are many questions surrounding data quality concerns. Answering these questions can help an MDM solution to determine what business and integration rules are required to bring the best data from the various sources together. This best-available master data is integrated under the MDM umbrella and should be entity-resolved, cleansed, rationalized, integrated, and then synchronized with the operational data systems.

Data Visibility, Security, and Regulatory Compliance

Solving challenges of data quality and data integration allows MDM solutions to enable entity-centric business process transformation. In the case of MDM for Customer Domain and as part of this transformation, the MDM platform creates a fully integrated view of the customers and their relationships with the enterprise, information that most likely has to be protected according to a multitude of various government and industry regulations. Or, stating it slightly differently, integrating customer information in an MDM Data Hub supports enterprise-wide customer-centric transformations that in turn create significant competitive advantages for the enterprise. At the same time, however, precisely because an MDM system integrates master data, including customer data, in one place called a “Data Hub,” these implementations face significant security and compliance risks.

The majority of the relevant regulations discussed here focus on the financial services segment and deal with the need to protect customer data from corruption as well as compromised, unauthorized access and use. In addition, a number of government and industry regulations require an enterprise to capture and enforce customer privacy preferences. Parts III and IV of this book provide a detailed look into the requirements for data protection and their impact on the technology of MDM solutions.

We offer a brief overview of the data protection and privacy regulations in this section for the purposes of completeness and ease of reference.

Basel II and FFIEC

Basel II defines operational risk to include the risk of compromise and fraud. Therefore, when the Federal Financial Institutions Examination Council (FFIEC) stipulated its latest guidance, it immediately affected the scope of Basel II’s operational risk in these specific ways:

• In order to combat fraud, on October 12, 2005, the FFIEC issued new guidance on customer authentication for online banking services. The guidance stated that U.S. banks would be expected to comply with the rules by the end of 2006.

• These new regulations guided banks to apply two major methods:

• Risk assessment Banks must assess the risk of the various activities taking place on their Internet banking sites.

• Risk-based authentication Banks must apply stronger authentication for high-risk transactions.

• Specific guidelines required banks to implement the following:

• Layered security

• Monitoring and reporting

• Configurable authentication, where its strength depends on degree of risk

• Customer awareness and reverse authentication

• Single-factor and multifactor authentication

• Mutual authentication

The USA Patriot Act’s KYC Provision

MDM data-protection concerns are driven by regulations such as the USA Patriot Act and the Basel Committee’s “Customer Due Diligence for Banks,” issued in October 2001. The USA Patriot Act specifies requirements to comply with Know Your Customer (KYC) provisions. Banks with inadequate KYC policies are exposed to significant legal and reputation risks. Sound KYC policies and procedures protect the integrity of the bank and serve as remedies against money laundering, terrorist financing, and other unlawful activities. KYC is an important part of the risk-management practices of any bank, financial services institution, or insurance company. KYC requires a customer acceptance policy (opt-in/opt-out), customer identification, ongoing monitoring of high-risk accounts, and risk management. MDM-enabled customer identification is one of the key drivers for the enterprises to implement systems known as the Customer Identity Hub platform.

Customer Fraud Protection

One of the tenets of customer fraud protection is based on sound customer identification and recognition capabilities offered by MDM. According to IdentityGuard.com,12 over 28 million Americans have had their identity stolen in the past three years. According to the California research firm Javelin Strategy & Research, in 2005 there were 8.9 million identity theft victims in the U.S. alone, costing $56.6 billion! Fraud protection measures resulted only in some marginal improvements in recent years. According to the Privacy Rights Clearinghouse,13 the total one-year fraud amount decreased to $55.7 billion in 2006 and then to $49.3 billion in 2007.

The Sarbanes-Oxley Act

The Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002 requires public companies to implement internal controls over financial reporting, operations, and assets. The Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) requires that companies make regular disclosures about the strengths, weaknesses, and overall status of these controls. The implementation of these controls is heavily dependent on information technology. Sarbanes-Oxley’s demands for operational transparency, reporting, and controls fuel the needs for MDM implementations.

OFAC

The Office of Foreign Asset Control (OFAC) of the U.S. Department of the Treasury administers and enforces economic and trade sanctions against target countries, terrorists, international narcotic trafficking, and those entities engaged in activities related to the proliferation of weapons of mass destruction. Executive Order 13224 requires the OFAC to make available to customer-facing institutions a list of “blocked individuals” known as Specially Designated Nationals (SDNs). The executive order requires institutions to verify the identity of their customers against the “blocked list.” Clearly, an MDM solution is a valuable platform that can help to achieve OFAC compliance.

Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act (GLBA)

The Financial Modernization Act of 1999, also known as the Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act, includes provisions to protect consumers’ personal financial information held by financial institutions. There are three parts to the privacy requirements: the Financial Privacy Rule, the Safeguard Rule, and Pretexting provisions. The Financial Privacy Rule regulates the collection and disclosure of customer information. The Safeguards Rule requires enterprises to design, implement, and maintain safeguards to protect customer information. The Pretexting provisions of the GLBA protect consumers from individuals and companies that obtain the consumers’ personal information under false pretenses.

GLBA requires disclosure on what information a company can collect, the usage of the collected information, what information can or cannot be disclosed, and the customer-specific opt-in/opt-out options. The Safeguard Rule includes a disclosure of the procedures used to protect customer information from unauthorized access or loss. For Internet users, the company must disclose the information collected when the user accesses the company’s website.

Given the potential scope and information value of data stored in MDM Data Hubs, it is easy to see why MDM implementations should consider GLBA compliance as one of the key risk-mitigation strategies.

The UK Financial Services Act

The UK Financial Services Act (1986) requires companies to match customer records against lists of banned individuals (terrorists, money launderers, and others) more rapidly and accurately. An MDM Data Hub is an effective data enabler to conduct these matches.

DNC Compliance

As part of their privacy protection campaign, the United States and later Canada accepted Do Not Call (DNC) legislation. In order to avoid penalties, telemarketers must comply with this regulation, which may also require some level of customer recognition and identification.

The legislation requires the companies to maintain their customers’ opt-in/opt-out options. Customer-centric MDM implementations allow the enterprise to capture and enforce DNC preferences at the customer level as well as at the account level. Chapter 7 illustrates this concept by discussing a high-level MDM data model.

CPNI Compliance

The Consumer Proprietary Network Information (CPNI) regulation prohibits telephone companies from using information identifying whom customers call, when they call, and the kinds of phone services they purchased for marketing purposes without customer consent. This creates the need for the opt-in/opt-out support and offers a platform to drive CPNI compliance.

HIPAA

The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) of 1996 (45 CFR Parts 160 and 164) requires the federal government to protect the privacy of personal health information by issuing national standards. An MDM Data Hub for a healthcare provider or a pharmaceutical company may contain comprehensive and complete personal health information at the customer/patient levels. Thus, HIPAA directly affects the design and implementation of MDM solutions that deal with customer health information.

ARRA

The American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA) is an economic stimulus package signed by President Barack H. Obama into law in February of 2009. One of the five stated intents of the ARRA is to provide investments needed to increase economic efficiency by spurring technological advances in science and health. The $19 billion allocated to Health Information Technology are expected to accelerate the adoption of MDM and other technologies.

Internationalization of Data Protection

Many countries have been developing their own data-protection regulations. There is a clear need for internationalization of these regulations. In its absence, all nations experience additional costs associated with a variety of information-sharing laws. The 31st International Data Protection Commissioners Conference,14 hosted by the Spanish Data Protection Agency (AEPD) in Madrid, Spain, in 2009, discussed movement toward an international regulation on privacy.15 These types of international regulations can have a significant impact on many areas of global information management, including MDM.

In conclusion, these sections demonstrate that although MDM solutions can offer significant benefits to an enterprise, these solutions are not easy to develop and deploy. Furthermore, an organization has to address many challenges when it embarks on an MDM initiative, including significant benefits; competitive advantages; and major additional technical, organizational, and business challenges related to an MDM-enabled transformation toward entity centricity and, in particular, customer centricity. We discuss many of these challenges, issues, and approaches in more details in Parts II, III, and IV of this book.

Challenges of Global MDM Implementations