CHAPTER 12

Building a Business Case and roadmap for MDM

When an enterprise entertains the idea of a Master Data Management (MDM) program, it has to create a justifiable business case and successfully complete an MDM investment funding request phase in order to initiate the program. The successful business case is critically dependent on securing executive management commitment and organizational stakeholder buy-in. This is the reason why so many publications have been devoted to the business case, value proposition, and justification of MDM and other information- and data-centric initiatives.

Importance of the MDM Business Case and the Current State of the Problem

A business case for MDM remains a significant challenge for many organizations. Many MDM initiatives are entertained and discussed for years and fail to get started because key stakeholders are not able to develop a common vision and reach consensus on the business case for MDM and justify the investment. This lack of clarity and consensus costs a lot to the organizations in terms of the time spent on the discussions and in terms of a lost opportunity due to the failure to execute a program that could provide a competitive advantage. The cost of such a failure can have reputational implications for the individuals who championed the initiative and were on point to develop the business case.

Many publications and presentations are available in the public domain that discuss and teach how to justify MDM and calculate the return on investment (ROI). Oftentimes these publications and presentations are not actionable and present an overly simplistic picture of the business case justification and MDM funding phase without taking into account the variety and complexity of scenarios and factors that impact the business case justification process. Many publications are written with the thought in mind that an MDM initiative is always a good idea. A reality is that for some organizations an enterprise MDM may not be the right priority at a given point in time or, even more, the costs of the program may exceed the benefits that can be realized as a result of the program. The devil is in the details, and the quality of the business case analysis or lack thereof can result in a highly profitable MDM initiative or make it a total waste.

Hypothetical MDM business case estimations representing an “average” company may not apply to your organization. A real cost-benefit analysis in your enterprise may show significant deviations (up or down) from the average estimated for a hypothetical company. It is highly probable that the deviation will exceed the average, which tells us that it is critically important to understand the challenges of business case justification of MDM and the techniques that can help your organization to build a compelling business case.

This chapter intends to help program managers, planners, solution architects, and other MDM stakeholders tasked by executive management or compelled on their own to develop a business case for MDM. It is important to understand that there are no shortcuts in approaching business case development for MDM. Hence, we will not even try to provide a “silver bullet” recipe for the MDM business case conundrum. Instead, this chapter aims at to provide the reader with an analysis of a variety of scenarios, considerations, and factors that should be understood and taken into account in order to build the business case for MDM properly.

Once these factors, scenarios, and their impacts are understood, MDM stakeholders are in a much better position to determine the risks of the funding phase and mitigation strategies. We will discuss what works and what does not work to help the reader avoid some common mistakes made by some practitioners during MDM business case justification efforts. This discussion is critical to the success of a strong business case that will move an MDM program into execution mode.

MDM Sponsorship Scenarios and Their Challenges

The idea that an organization needs an MDM environment comes and is incubated within organizations as a combination of two primary sponsorship scenarios:

• Business strategy–driven MDM

• IT strategy–driven MDM

Both scenarios are quite common and can result in successful business case justification and the overall success of the MDM initiative. Having said that, it is much easier to justify MDM when there is a solid business strategy behind it, and oftentimes what drives the business case is a combination of business and IT factors.

Business Strategy–Driven MDM

When MDM is driven by a business strategy, the imperative for a change comes from executive management (CEO, CFO, or divisional leadership). In this scenario, executive management is sick and tired of operational inefficiencies as well as the lack of the enterprise’s ability to interact with the customer holistically and report on master entity–centric metrics, where master entity is customer, product, location, supplier, service, and so on. Executive management has a strategic business vision of a change and demands it.

The initiative is typically executed under mottos and mantras such as “Customer Experience,” “One Organization, One Customer,” “Customer 360 Strategy,” “Global Account Opening and Management,” “Global Policy Issuance and Management,” “One View of a Guest,” “Health Electronic Record,” and other names that vary by industry. It is quite common that IT is not able to recommend a quick fix to support the new business strategy. Legacy processes and platforms may create formidable obstacles and preclude any attempts to quickly fix the problem without significant investments and structural changes that require a new IT vision and strategy to support the change.

The new IT strategy and its elaboration may include a number of priority projects:

• A new core operational system to replace the existing legacy platform that has been in production for 20–30 years

• Development of service-oriented architecture (SOA) that includes an Enterprise Service Bus (ESB) for messaging, interoperability, and increased agility of business processes

• Selection of a Business Rules Engine software

• Development of a new conceptual master data model

• Other foundational changes related to MDM and data quality.

Considering these projects could become a pivotal point in the program life-cycle when business executives may learn about the existence of the term “MDM” for the first time, even though it turns out to be one of the core foundational components required to execute the business strategy. This is not always a bad thing; the goal here is not to complicate the business strategy with detailed IT aspects too early.

To sum up, in the business strategy–driven scenario, business executives have a vision that implicitly points to the need for MDM. In this scenario, MDM is a critical part of a larger initiative that supports or implements the business strategy. Clearly, this scenario makes the development of the business case for MDM and the overall MDM justification much easier because it is subsumed in the larger vision for change in the business.

IT Strategy–Driven MDM

About 50 percent of MDM programs are driven by IT organizations as an IT strategy initiative. This scenario makes the MDM business case more challenging because typically IT management cannot approach the business case problem with the same degree of power and authority as business executive management in the business strategy–driven MDM scenario.

IT strategy–driven MDM efforts sometimes focus mostly on implementations of MDM software and the creation of a “golden” record in the MDM Data Hub, while leaving the analysis of consuming applications and processes that will be enabled by MDM for the consequent phases. This approach may cause problems in relationships with the business, negatively impact end user adoption, and can even cause the initiative to fail.

If this view prevails in the enterprise, an MDM initiative can be perceived by many as a massive infrastructure improvement project that requires significant efforts and investments while lacking tangible business and operational benefits. This is a common challenge for many MDM initiatives driven by IT organizations, and this perception of MDM as an infrastructure-driven investment should be addressed as a part of business case development.

Some MDM experts have even expressed an opinion that MDM initiatives driven by IT are doomed. In reality, many IT strategy–driven initiatives succeed if they engage the business properly and in a timely manner. Some IT leaders, especially those who have spent over 15–20 years with the company, have acquired a broad understanding of business and operational issues and are well positioned to champion the initiative.

What MDM Stakeholders Want to Know

The challenges of the MDM business case grow with the number of stakeholders. Different groups of stakeholders see MDM from different perspectives and approach the funding/no-funding decision with different criteria and agendas. Thus, individuals responsible for a justification of MDM also have to approach the business case from multiple perspectives and explore a variety of methods to tackle the business case justification problem properly.

Managers responsible for MDM business case justification should have a mindset of a salesperson engaged in complex technical sales. The book Hope Is Not a Strategy, by Rick Page, introduces the concept of a “Shark Chart” that describes a variety of stakeholder levels and roles.1 The overall approach and methodology in this book is a good example of what the individuals responsible for MDM business case justification should adopt.

At the very strategic level, the board of directors and CEO want to know how the equity value, market capitalization, and competitive posture of the company would change as a result of the initiative that includes MDM. Executive management wishes to know which divisions/lines of business (LOBs) will benefit from the MDM initiative and how. They want to hear that divisional leadership supports the initiative and understands its benefits, risks, and costs.

A CFO may require ROI and NPV (Net Present Value) calculations. Oftentimes, for a CFO the cost of the initiative is more important than the benefits, even though the CFO may rely on the business leadership opinion that the change promised by the initiative is indeed required. The CFO wants to have a solid understanding of the initiative’s costs to prevent a potential long-term cash flow problem. To make the CFO a supporter of the initiative, the business case justification team needs a solid understanding of what type of MDM solution will be implemented, what components will be used, what processes will change, and what resources will be required. Then the team can develop an implementation roadmap that is detailed enough to substantiate cost estimates with a reasonable certainty.

For large (Fortune 1000) firms, a division can be considered an enterprise in its own right. Then an enterprise MDM may be limited to the division or even a line of business. In this scenario, the head of the LOB is considered to be in the role of the CEO from the MDM sponsorship perspective.

Even if the LOB management does not sponsor the initiative championed by their superior executive management, the LOB support is absolutely critical. LOB leaders are looking to understand tactical changes in the LOB processes and user interfaces that the initiative will bring in. They want to understand what resources from their organization will be engaged in the initiative and thus distracted from their current functions and responsibilities.

Information strategists and enterprise architects are looking to see how well the new MDM architecture will comply with applicable architecture standards and fit their enterprise architecture vision. Operations management, database administrators, and individuals who will be responsible for the maintenance of MDM components have significant stakes in the MDM solution, too. In Chapter 13 we will discuss in more detail the key questions a typical organization has to understand for MDM program initiation.

Business Processes and MDM Drivers

Business processes that will be improved as a result of MDM vary by industry, company, program, and even by the phase of the MDM initiative. Still, there are common areas and processes that are typically improved by MDM.

We discussed the predominant MDM drivers and the areas that benefit from MDM in Figure 2-2 of Chapter 2. The most common beneficiaries of MDM are listed there. This list can help an MDM team charged with the responsibility to define the business case and justify the investment. Leveraging the table in Figure 2-2 as a starting point, the business case definition team can prioritize the drivers as needed and adjust the list of drivers to better reflect the business context of the MDM program in their organization.

One of the considerations for prioritization is based on economic conditions: In the time of economic downturns, we see an increased focus on operational efficiency. Conversely, when the economy grows fast, MDM initiatives tend to focus more on the enablement of new business opportunities and processes.

Benefits and Their Estimation

Benefits are often divided into two categories: quantitative and qualitative. Quantitative benefits (that is, “hard” benefits) are those that can be estimated from cost savings, the enablement of new revenue opportunities, or the avoidance of scenarios in which a revenue opportunity will be lost (for example, due to customer attrition). Qualitative benefits deal with “softer” aspects such as reputation risks, company competitiveness, potential compliance issues that may be very significant for business but not easily quantifiable, and so on.

In reality, there is no wall between qualitative and quantitative benefits. Some benefits that are considered quantitative may be difficult to evaluate for a given company in the context of its current business processes. On the other hand, benefits traditionally placed in the qualitative category can sometimes be evaluated and measured. For instance, benefits of improved compliance2 are sometimes estimated in terms of avoided penalties that an enterprise can be subjected to without the improvements promised by MDM. It is difficult, however, to quantify the cost of corporate scandals and ruined reputation of a company and its top executives, along with the potential legal consequences these executives might be subjected to.

From the business case methodology perspective, two high-level approaches can be used to estimate an MDM impact:

• A traditional bottom-up approach This approach quantifies MDM benefits by performing an in-depth analysis of the current-state processes, identifying their inefficiencies, and developing an ROI model by showing how MDM can reduce costs and increase the revenue.

• A less traditional Economic Value (EV) approach This approach provides a high-level estimate for the business impact of MDM and other information-centric initiatives (this is different from a more traditional Economic Value Added or EVA metric, which is a measure of the financial performance of the company that represents an estimate of economic profit).

Traditional Methods for Estimation of Business Benefits

As well explained by David Linthicum in his online article “Defining the ROI for Data Integration,”3 the business case begins with the definition of the problem domain. The drivers outlined in the previous section define the most common high-level problem domains for MDM.

If your organization’s ROI and NPV estimations require a more detailed list of problem domains and processes, you can benefit from a number of articles where a variety of benefits achieved through improved data quality and improved management of master data are discussed in detail.4,5,6,7,8

Let’s consider a simple business case scenario where an enterprise seeks to implement MDM because its current process heavily relies on a third-party supplier of customer data. The enterprise pays $4 million to the supplier annually. In addition to being on a continuous cash outflow, the enterprise suffers from a lack of agility to support changing business requirements. The enterprise makes a decision to implement an MDM solution and discontinue the subscription to the third-party data.

The initial implementation costs, including the MDM software license cost, integration services, acquisition of new hardware, training, and other initial expenses are estimated at $3 million. On completion of the MDM implementation, the total of on going annual expenses is estimated at $400,000, which may include the annual software license fee, cost of data stewardship resources, maintenance, and other on going costs.

In this example, in the first year after implementation the enterprise will spend $3.4 million on MDM. Because the third-party data subscription is canceled, the $4 million cost was avoided, which results in a total cost savings of $0.6 million in the first year. Every consequent year will provide an additional $3.6 million in savings. In five years after implementation, the $5 million total investment will result in $20 million of cost avoidance, which translates into the following:

(20 –5) / 5 * 100% = 300% ROI over five years and $15M Net Present Value (NPV)

Even though we didn’t put a dollar tag on the increased agility to support changing business needs, we identified inefficiency ($4 million annually) and found a way to eliminate it by making a profitable investment in MDM products and services. In this example, the problem domain was very well defined and the ROI model was simple. Unfortunately, these simple ROI scenarios for MDM are rather limited.

Let’s discuss another example of the MDM business case typical for marketing applications that are often addressed by analytical MDM. A company runs several mail marketing campaigns annually with a total of 10,000,000 mailings. The company has estimated that 10 percent of the mailings are sent with at least one of the following errors:

• The mailing address is incorrect and as a result the mailing does not reach the recipient.

• More than one letter is sent to the same person.

• More than one letter is sent to the same household because the enterprise lacks the capabilities to identify households, even though the business would like to be able to market to households rather than to individuals.

The company decides that if it implements MDM for its Customer domain, the 10-percent error rate will be practically eliminated. This yields estimated savings of $500,000 annually, assuming each mailing costs 50 cents. In this scenario, assuming the cost of the MDM implementation is the same as described in the previous example, the company will save only $100,000 annually: $500,000 savings less $400,000 spent on the on going expenditures. In order to offset the initial MDM investment ($3 million) and to break even, the company will need 30 years! This is too long for any reasonable investment return, especially if you consider an impact of inflation that would drive the real value of the currency (for example, U.S. dollar) to drop significantly over this period of time.

In this case, the estimate cannot justify the MDM investment. It does not mean, however, that the enterprise has considered all of the benefits that can be realized from the MDM implementation. For instance, the marketing department considering an MDM investment may want to develop an advanced market segmentation model, which requires MDM as a component of the solution. Indeed, by definition, the MDM system will integrate customer information from multiple systems and possibly third-party sources and will create and maintain one holistic view of the customer and household. This holistic view is the basis that would enable marketing segmentation software to deliver accurate segmentation models, thus justifying the need for MDM as the enabler and the catalyst of improved marketing efficiency.

The preceding scenario highlights some of the challenges typical for business case estimations:

• The company estimated a 10-percent error rate in mail delivery. In reality, it is often a challenge to determine the actual error rate. Ten percent is most likely a guess. The real rate can be significantly higher or lower.

• If market segmentation is one of the applications planned for the implementation, the invested amount should be calculated for the whole market segmentation project, with MDM being only one of its components. Hence, the baseline project cost will be higher than $3 million and the annual cost will be higher than $400,000.

• The total value of the benefits should be calculated as a sum of the mailing savings and the savings and/or revenue opportunities associated with the new market segmentation capabilities and processes.

• A number of books and numerous articles discuss the metrics estimating efficiency of marketing campaigns. These metrics require accurate measurements of the outcomes of marketing campaigns, which is not a simple task.9 Many companies do not measure the efficiency of marketing campaigns, which complicates the quantification of the MDM business case because the impact of MDM cannot be measured in business terms. If the business itself does not measure its efficiency, it is difficult to estimate the incremental business impact of MDM on the business.

In the marketing segmentation scenario, we noted that cost savings from improved mailings did not provide enough savings to make an MDM project profitable. It is not unusual that in addition to cost savings, the business case has to take into account the new revenue opportunities to justify the investment.

Cost savings can be achieved through the reduction of resources involved in the process. The top resources that can provide savings include:

• Employees (measured as full-time equivalents, or FTEs) This includes not just headcount reduction but also reduced administrative overhead, better process automation, organization, and improved productivity.

• IT infrastructure (hardware) cost through better architected data management with improved data redundancy This will increase the efficiencies and reduce the costs of systems where master data may reside.

The team responsible for the MDM business case should be prepared to answer the CFO’s questions, such as the following: “OK, you say that we will be able to reduce the number of people engaged in the current process. Can you be more specific on how many employees, fixed price and time and material consultants, and other temporary workers the company will be able to free or reassign to fill other openings? What infrastructure components can we save on if we purchase a vendor MDM Data Hub product?” These questions can put the MDM business case team in a politically difficult situation, especially as it relates to the opportunity of FTE reduction. Indeed, let’s estimate how many FTEs should be released from the process to make an MDM investment profitable. Assuming the annual FTE cost of $50,000 per employee, in order to break even with the MDM investment defined earlier, we will need to reduce the workforce by 23 employees immediately in order to break even in four years! Indeed, the savings from reducing the number of employees by 23 yield 23 * 50,000 = $1,150,000 annually or $4,600,000 for 4 years. The same amount will be spent by the enterprise on MDM: $3 million for the initial investment and $1.6 million on the maintenance ($400,000 annually for 4 years). This perspective may put you at odds with many people in your organization and defeat the idea of MDM.

This emphasizes an important point: In many scenarios cost savings may not be able to justify the investment. You should be prepared to inspire the organization with new revenue opportunities enabled by MDM to develop a sound business case. The business should be willing to champion the ideas of new revenue opportunities enabled by MDM. This may bring a new business strategy that will help MDM business case justification.

It should be pointed out that in a number of projects similar to our marketing mailing scenario, a business case was originally defined in terms of savings achieved through a reduction of mailings. Later, when the project went into production, the enterprise chose to keep the number of mailings the same while benefiting from significantly improved quality of marketing campaigns (lift) that brought in significant incremental revenue.

Some companies, after an in-depth analysis of their processes, came up with the cost of a duplicate master record between $20 and $60 per record, which is two orders of magnitude higher than the cost estimated from the model based on the duplicate mailing scenario. This is another indication that those easily quantifiable benefits provide only a small fraction of the real value that MDM can provide. The cost of $40 per duplicate can be used as a rule of thumb for high-level estimates if a detailed business process analysis has not been performed by the enterprise. In the authors’ experience, this estimate works well for enterprises where the number of customers is high (for instance, greater than 15 to 20 million records).

As we can see from this discussion, the complexity of a bottom-up business case can range from a relatively simple scenario when one or a few specific and easily quantifiable problem domains justify an investment, to a variety of complex scenarios where only a long list of cost avoidance areas in combination with multiple revenue opportunities can justify the business case for MDM.

Economic Value of Information as MDM Business Case Estimation Technique

Robert Hillard and Sean McClowry10 formulated an alternate approach to business case justification for information-centric initiatives such as MDM. Instead of tackling the business case challenges bottom-up through an in-depth analysis of business process inefficiencies that can be cured by MDM, the top-down approach introduces the notion of an EV of information and applies a Capability Maturity Model (CMM) approach.

It is always a challenge to put a dollar value on information without knowing its content and the context in which it can be used. The EV model approaches this challenge by establishing a relationship between the market value of the enterprise and the value of the enterprise information. The EV of information is defined as

EV of Information = P(Information) * Market Capitalization

where P(Information) is a parameter of the model that indicates what fraction of the corporate market capitalization falls under informational assets. Hillard and McClowry recommend P = 0.2, even though they report that this estimate is fairly conservative. This value was obtained as a result of a number of workshops and interviews with corporate executives.

We have adapted this method to MDM. The preceding EV can be rewritten for MDM as

EV of Master Data = P(MDM) * Market Capitalization

where P(MDM) indicates what fraction of the corporate market capitalization falls under MDM assets.

This formula has been used on a number of practical MDM implementations. The results show that the value of parameter P(MDM) is typically in the range of 0.03–0.06. For example, let’s apply this approach to an enterprise with a market capitalization of $3 billion. Assuming P(MDM) = 0.04, then the dollar equivalent of the enterprise master data will be equal to $120 million. This is what the enterprise master data would be worth if the Master Data Management initiative was executed perfectly.

MDM Capability Maturity Model

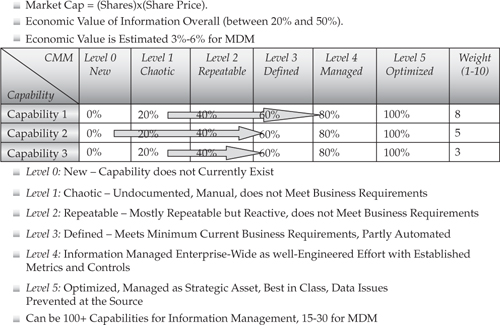

To use the EV approach effectively, the enterprise should define 15–30 capabilities, processes that are to be enabled, and problem domains that are to be fixed by the enterprise via MDM. For each capability, the current state, the expected target state, and the relative importance of the capability are identified as depicted in Figure 12-1.

FIGURE 12-1 Economic Value approach to information and MDM

Generic guidance on the definitions of maturity levels (1–5) can be found in numerous books and articles on CMM and IMM. Rob Karel2 recommends definitions of five maturity levels of MDM, along with typical enabling technologies and usage scenarios for each MDM maturity level. Karel’s definitions can be leveraged as a guide to define maturity levels for each of the capabilities. David Loshin11 has defined MDM maturity levels by grouping MDM capabilities into the following categories:

• Architecture

• Governance

• Management

• Identification

• Integration

• Business Process Management

The MDM management team should understand the overall approach to CMM and the definition of capabilities, evaluation categories, and tactical views for MDM benefits. You can read more on these in the references given at the end of the chapter.2,4,8,10

Using this information as a guide, MDM stakeholders can make informed decisions on which capabilities best fit their MDM objectives and organizational culture. The process of evaluating the current state for each of the categories identified for a given MDM initiative and understanding the expected target state and the incremental releases in terms of CMM for MDM is a great exercise that helps key MDM stakeholders to get on the same page and agree on their views on what drives their MDM initiative (readers who would like to find additional information on this topic can review the series of blogs titled “Estimating the Benefits for MDM”).12

In discussing CMM for MDM, we extend the traditional CMM model by adding maturity level 0 to denote the capability that currently does not exist but is on the enterprise wish list, which means that the enterprise is planning to develop this new capability that can be a new business process or even a line of business.

The arrows in Figure 12-1 indicate that a given capability would be created and/or enhanced across several maturity levels. For example, Capability 1 will be enhanced from Maturity Level 1 to Maturity Level 4, while Capability 2 will be increased from Level 0 to Level 3.

The following formula defines an incremental increase in the market cap of the enterprise when the target capabilities enabled by MDM are achieved:

![]()

In this formula, σ stands for the summation over all capabilities that will change, and Wi and ΔLi are the relative importance and expected maturity level change as a result of the MDM implementation.

One of the benefits of the EV approach is that a quantitative model can be built relatively quickly. The capabilities, their current and target states, as well as their relative values are defined in a few workshops with MDM stakeholders. The workshops are followed by an analysis of the obtained results. The EV approach can estimate the values that are practically impossible to obtain by the traditional bottom-up evaluation method. Even soft MDM benefits such as corporate reputation can be accounted for within the EV method. Indeed, the market capitalization depends on the company’s reputation, and therefore the incremental economic value obtained through MDM will take this factor into account.

MDM Economic Value workshops with broad representations of key stakeholders bring a great value as a technique that helps the enterprise to develop a common view on why they are pursuing MDM, to socialize the value of MDM, and to build organizational consensus.

A weakness of the EV method is that it provides only high-level estimates. Some companies and their CFOs get used to and require more traditional ROI and NPV estimates. They may be skeptical about the accuracy of the EV method.

For some capabilities, both approaches may be applicable. The quantitative values obtained from the two approaches can be compared to ensure reasonable consistency. The incremental increase in EV due to MDM is expected to be three to ten times greater than the total estimated value of the annual benefits calculated by the traditional bottom-up method. This rule of thumb can be used to validate the model and refine its parameters.

The best results are obtained when both approaches (EV and the traditional bottom-up approach) are used in concert. We believe that a combination of these methods will become the mainstream technique for MDM business case evaluations in the future.

The content presented thus far focuses mostly on the business benefits of MDM and the methods of their estimation. The benefits define the numerator in the ROI equation. For the ROI and NPV calculations, the cost structure is equally important. Thus, to complete the business case, a detailed analysis of the key early decision points that significantly impact the MDM roadmap, costs, risks, and mitigation strategies is also critical. These decision points and a high-level MDM roadmap must be developed as part of the business case to position the enterprise for a balanced and comprehensive cost-benefit analysis. The MDM roadmap should include a number of views critical for scope and costs estimations.

The importance of a balanced and properly defined MDM roadmap, along with the MDM development techniques, will be discussed in the remainder of this chapter.

Importance of the MDM Roadmap

In the previous sections of this chapter, we discussed MDM business benefits, methods of their estimation, and factors important to understand in order to successfully initiate an MDM program. Even if business benefits are estimated and understood by the enterprise, the business case for MDM is incomplete and cannot be quantified if the costs and risks are not estimated.

When an enterprise embarks on an MDM program, it is critical for the stakeholders to understand the key decision points that determine the initiative’s costs, risks, and risk mitigation strategies. An enterprise that begins an MDM program without a properly defined implementation roadmap will not be able to proactively understand the target state of MDM and its evolution from release to release. This will adversely impact planning and the ability to execute the program. Without proper understanding of the “what,” “when,” and, at a high level, “how,” it is impossible to articulate what benefits will be realized and when, what areas of the enterprise will be impacted when and how, and what resources (people, hardware, software, and so on) will be required.

Consequently, in the absence of a comprehensive MDM roadmap, it is not feasible to intelligently estimate the program costs and when they will be incurred. Without cost estimates, even if the benefits of MDM are clear, the enterprise cannot complete a cost-benefit analysis and estimate ROI and NPV. Ultimately the MDM stakeholders cannot make a substantive go/no-go decision about the MDM initiative. In the absence of a properly developed MDM roadmap, understanding and estimating the dependencies and risks is not feasible either.

A properly developed MDM roadmap, at a high level, defines program releases for the MDM evolution over one to five years. For a multiphase MDM program, the immediate phase is planned in more detail. The phases that follow are planned with decreasing levels of detail, while including enough information to drive the most important decisions.

For a multiphase MDM implementation, the MDM roadmap document is a “living summary” that evolves as the initiative progresses rather than a document created once at the beginning of the program and is never touched later.

Experience shows that on a number of MDM projects, the teams responsible for the program claimed to have an MDM roadmap. The analyses that followed showed that in many cases the roadmaps had been defined in a very superficial way and lacked critical details. The MDM roadmap definition was often limited by a single dimension: the data domains that will be addressed by MDM (for example, Phase 1: Customer, Phase 2: Location, Phase 3: Product, Phase 4: Other). Such a superficial roadmap does not provide enough information to estimate costs and resources, evaluate risk, and establish confidence among the stakeholders that they as a team have developed as a common MDM vision.

Some enterprises initiating MDM programs tend to fall to the other extreme. They try to envision many lower-level details that may not be predictable because the answers depend on factors that can be refined only in the future. The desire to understand and include too many details may result in an “analysis paralysis” scenario, where discussions that are supposed to refine questions generate many other unanswered questions and uncertainties. As a result, the initiative fails to start for months or even years.

The challenge of the MDM roadmap resides in prioritizing the most critical questions that greatly impact costs and risks while postponing other questions that are less important. Some questions are critical enough to be impactful, but they cannot be answered at the time of program commencement. In this case, it may be a good idea to identify potential solution options and the associated uncertainties and risks.

This section discusses the areas of the roadmap and decision points that are crucial for a typical MDM roadmap. The section provides recommendations on how to define a comprehensive MDM roadmap in terms of 20 MDM roadmap views that are discussed in the following subsections. Note that in our online blog series13 we introduced the term “MDM roadmap domains.” In this book we will consistently use the term “MDM roadmap views” instead to avoid the usage of the term “domain” in different contexts throughout the book, which may cause some confusion.

Basic MDM Costs

An MDM program’s cost can vary drastically. Some low-end home-grown solutions are built and maintained by one or two people. These types of solutions, although rudimentary in terms of their capabilities and industrial strength, can be well tailored to the business needs and valuable for the business, and thus are easy to understand and manage. Let’s consider an enterprise-scope MDM program and review the cost components of such a program.

We will assume that the reader is a stakeholder in an enterprise program that includes MDM Data Hub software purchased from one of the established MDM vendors.

Then the primary cost components include:

• Software

• Professional services for software installation, analysis, configuration, training, and on going support

• Hardware

• Initial integration

• On going maintenance and integration

• Data stewardship (optional)

• Subscription for third-party data providers (optional)

Some basic costs for a hypothetical company with 5 million customers were estimated14 by Rob Karel of Forrester Research, Inc. The total estimated cost of $3 million was incurred by the hypothetical company over the initial implementation and three years of production.

This included roughly 20 percent spent on the MDM Data Hub software license, 40 percent on the professional services work (installation, configuration, analysis, and integration), and 12 percent on the hardware. The remaining 28 percent was spent on the full-time resources— annual cost of IT maintenance ($270,000) and the annual cost of data steward resources ($81,000). These annual on going costs become predominant over the years in the described scenario. The estimate was performed for a single domain (Customer). No third-party data costs were included in the estimates.

Many MDM initiatives incur costs an order of magnitude higher than $3 million, whereas some other MDM initiatives are implemented with a fraction of the $3 million budget. Historically, some companies invested more in the initial product but ended up with significantly lower ongoing IT maintenance costs that determine the annual cash flow and the MDM cost of ownership from the longer-term perspective. Thus, the stakeholders of any MDM initiative should understand the factors responsible for cost variations of MDM initiatives through the analysis of the target state and the roadmap.

MDM Roadmap Views

In order to make the target state of MDM and the MDM roadmap reasonably comprehensive, the following roadmap views should be included in the roadmap development plan:

1. Business Benefits

2. Systems and Applications in Scope of MDM

3. Data Domains, Entities, and High-Level Data Model

4. Relationships, Hierarchies, and Metadata

5. Third-Party Data Sources

6. Systems Decommissioning Strategy

7. Data Hub Usage Style

8. Data Hub Architecture and Data Ownership Style

9. Data Volume, Performance, and Scalability Considerations

10. Reference Data Management

11. Deployment Strategies and User Groups

12. Related Initiatives

13. Master Data Governance Maturity

14. Master Data Quality Processes, Metrics, and Technology Support

15. Integration with Unstructured Data

16. Multilingual Requirements

17. Complexity of Cross-Domain Information Sharing

18. Complexity of Data Security and Visibility Requirements

19. People Resources and Skills

20. Enabling Technologies: ETL, SOA, and ESB

As you can see from this list, these roadmap views address MDM project concerns holistically and touch upon business drivers, data architecture, systems architecture, organization and governance, security and compliance, development life cycle, and system and master data maintenance. One of the key values of the roadmap view approach is its ability to make the roadmap agile and active, so it can be easily adjusted as business requirements change.

Some views may be more important than others for a specific enterprise. Still, it is a good idea to look at all of them first, prioritize some of them, and possibly de-prioritize some others based on your enterprise’s needs.

Business Benefits

The Business Benefits view tops the list of roadmap views. As we stated earlier in this chapter, the business case cannot be considered complete without a sound roadmap that determines the primary cost parameters. The reverse statement is also valid. An MDM roadmap should consider business benefits by release or implementation phase. MDM stakeholders want to know what groups will benefit from the program, how, and when. Some groups may be enthusiastic about the coming change promised by MDM. Some others can be cautious and even reluctant to accept the coming changes and the new business processes enabled by MDM. The reluctance to adopt MDM represents a risk for the initiative, and the motivations of this reluctance need to be understood. Business benefits, their priorities, and timing can indirectly impact the costs. For instance, if the initial phase of the initiative is focused on marketing, this focus is an indication that an analytical MDM solution will be implemented. The cost and implementation risks of an analytical MDM are typically lower than those for an operational MDM. We will focus on this aspect over the discussion of the Data Hub Usage Style roadmap view.

Systems and Applications in Scope of MDM

It is not unusual to have 20–40 systems and even more in the scope of a long-term MDM data and systems integration. Significant cost savings can be achieved by standardizing systems’ on-boarding procedures. Even though different systems may have different integration modes that depend on the latency requirements, data exchange attributes, merge and split requirements, and other solution characteristics, it is important to define a finite number of standard systems’ on-boarding procedures that the enterprise will leverage for MDM integration. Once these standard procedures are established during the first MDM implementation phase, they can be reused to effectively contain the cost of the subsequent phases. The enterprise cannot afford a scenario where every additional system is integrated with the Data Hub as an independent project that does not leverage the previously developed systems’ on-boarding procedures, standards, and data and systems integration techniques.

Data Domains, Entities, and High-Level Data Model

Although early MDM implementations were primarily focused on a single MDM domain (for example, Customer or Product), the current trend is shifting to multidomain MDM solutions. Thus, the majority of recent and current MDM implementations have a multidomain perspective, even though the initial phase oftentimes concentrates on a single domain. An MDM team that approaches MDM with a multidomain perspective must make sure that the MDM product they select can handle multiple domains. The recommended way of doing this is to select an MDM product with a data domain–agnostic data model and services.

Standardization of systems’ on-boarding procedures will help here, too. This standardization approach will help constrain future per-phase costs in which new data domains are added to the MDM scope. This can make investments in the integration of new data domains an order of magnitude lower than the costs of the first MDM data domain.

When evaluating the complexity and potential cost of the implementation, it is important to understand the complexity of the key data domains. A master data model can greatly help in the understanding of the level of MDM complexity. Even when a single-domain MDM is being implemented (for example, Customer), the overall party model can be fairly complex and consist of 20–30 entities in the 3NF representation. The complexity of the model grows with the introduction of multiple entity definitions (customer, client, and so on) that can coexist within each of the domains. More specifically, it is not unusual for an enterprise to have 10–15 definitions of a customer that depend on the context, department, or function. For instance, the term “customer” can apply to an individual, a household (which can be defined in multiple ways), a trust fund, or a commercial institution. For shipping and logistics applications, the intersection of a customer and location attributes can represent a new definition of a customer. Marketing, billing, and compliance departments can have very different definitions of a customer. A combination of this variety of customer views can result in a complex party model. Availability and reasonable completeness of the master model helps reduce uncertainties in planning and cost estimations. It is not expected from the model to be complete for early estimates. Still, the change in scope between a single entity with 20 attributes that later unexpectedly evolves into a relatively complex data model with 20–30 entities and many hundreds of attributes can impact the accuracy of planning, resources, and the cost estimates. As we showed in Chapter 7, the size and maturity of the MDM data model are important parameters for the planning of an MDM solution.

Relationships, Hierarchies, and Metadata

The value of MDM greatly depends on what the program does to manage relationships between master entities. See the discussions on the importance of relationships on the online resources given at the end of the chapter.13,14,15

Any mature MDM solution includes strong support for relationship management. A holistic and panoramic view of a customer includes a comprehensive view of relationships. As we discussed in the previous section, various enterprise functions require different views and definitions of entities. The same applies to relationships. Understanding relationships between parties and products as well as customer and product hierarchies is critical for enterprises. It is quite common for an MDM program to begin with one or a few master entities and then evolve into a multidomain MDM with a strong focus on relationships. At a high level, three techniques are used to build entity relationships and hierarchies:

• Use an external trusted source of relationships (or multiple trusted sources) and build relationships and hierarchies by comparing in-house master data with external trusted sources.

• Define the rules that will be used to algorithmically infer relationships. These rules can be based on common attribute values (for example, people sharing the same home address are defined as a household). The attributes can be matched exactly or probabilistically by applying the same probabilistic and fuzzy methods that are used for entity resolution (we discussed this process in Part II of the book).

• Link relationships manually by using graphical interfaces. This method requires additional data stewardship resources and therefore additional costs associated with data stewardship.

Each method has its inherent benefits, areas of applicability, and limitations. In full-scale MDM implementations, enterprises can benefit from using all three methods to create and maintain a comprehensive view of relationships.

The use of each of these methods can, on the one hand, increase the value of the MDM solution while increasing the MDM implementation cost.

Organizing data domains into hierarchies and providing capabilities to create, change, manage, and link hierarchies is a critical and complex area of an MDM solution that needs to be well understood and carefully estimated depending on the number and complexity of business requirements for hierarchy management and its proposed applicability to downstream systems. In addition, both the relationship and hierarchy management require the support of a metadata repository and a metadata management facility, a complex area of technology that should be considered as a key part of the MDM roadmap. (See the discussion on hierarchy management in Chapter 4 and the discussion on metadata in Chapter 5.)

Third-Party Data Sources

An MDM solution can greatly benefit from the use of third-party data. A Data Hub matches enterprise master data with the third-party data, which helps to improve the quality of the matching process and enhances entity and relationship resolution. Third-party data also helps in the development of customer and product hierarchies. External trusted sources can improve data quality and enrich enterprise master data.

There are costs associated with third-party data. These include the costs of data subscriptions and the costs of integration with trusted sources. Specifics of the third-party source or sources, their usage, and integration modes will impact the total cost.

Decommissioning of Systems and Applications

Significant long-term cost savings can be achieved if some systems or applications are decommissioned as a result of an MDM program. Systems decommissioning can free people and system resources. It can also result in cost avoidance if there exists a license maintenance cost associated with the decommissioned systems. For the most part, companies tend to add MDM Data Hub systems to their existing environments. An addition of any system, no matter how well it is architected, causes some incremental complexity in the overall system and data management. It is important to look at what workflows can be improved or eliminated and what systems can be decommissioned as a result of the MDM implementation.

Therefore, if systems decommissioning is a part of the program, the decommissioning and related activities should be looked upon as a roadmap dimension. The decommissioning effort can be responsible for some additional costs in the short term but can provide significant long-term operational and cost-reduction benefits.

If systems decommissioning is planned only in the future phases, a decommissioning strategy is still an important consideration that may impact MDM solution design decisions. If the strategy is to phase out a legacy system, the enterprise may not be willing to invest in new integration interfaces for the legacy system that is planned to be decommissioned.

Data Hub Usage Style

As we discussed in Part II of this book, three primary MDM usage styles determine the usage focus of MDM:

• Analytical

• Operational

• Collaborative

Analytical MDM concentrates on data warehousing, business intelligence, reporting, and analytical applications. Within an analytical MDM implementation, the Data Hub obtains data from operational systems, processes the data to resolve entities and relationships, and sends high-quality data to the consuming analytical systems. An integration style where the data flows in one direction and bidirectional synchronization is not required results in lower risks and costs. Analytical MDM has the lowest costs and implementation risks.

Operational MDM typically requires bidirectional synchronization between the Data Hub and operational systems, which increases the cost and risk. And Collaborative MDM supports complex workflows and can include the needs to support a supply chain application with multiple branching points that depend on the actions and choices of the workflow stakeholders. This process is quite typical for Product Information Management (PIM) and can be fairly complex.

When the benefits of MDM are estimated, all of the usage styles should be considered. They can collectively contribute to the total value of the benefits of an MDM program. Similarly, the total cost depends on the usage styles and when/where in the MDM roadmap these styles are deployed. The MDM usage style can evolve over phases of the MDM program. From the cost and risk perspectives, a practical approach is to consider beginning the initiative with Analytical MDM. Of course, this is just an option; business requirements can change the focus and usage style implementation sequence (for example, the business prefers an operational MDM focus from the very beginning). This is likely to cause an increase of the implementation cost.

Data Hub Architecture and Data Ownership Style

We have discussed Data Hub architecture and data ownership styles in Part II of this book. The three primary Data Hub styles are

• Registry

• Coexistence

• Hybrid Transaction

Typically, the Registry style, with possibly some hybrid features, is the least risky and the most efficient way to implement the Data Hub while maximizing business benefits and minimizing risks and costs. The Registry style arbitrates the data across multiple operational systems that retain the ownership of the master data.

Contrast this with two scenarios that work in favor of the Transaction style:

• The master entity that is to be managed by the Data Hub has not been supported by the present operations. For instance, an organization wants to build an entity called “Provider” that has not been managed before.

• The other scenario that favors the Transaction Hub choice for implementation applies to projects where the existing processes are already entity-centric (for example, customer centric). The MDM project objective is to replace the existing customer-centric database with a new industrial-strength MDM Data Hub while preserving the entity-centric flows.

For either style, the complexities of the match, merge (attribute survivorship), and split rules should be taken into account; solution options should be analyzed, and associated costs should be estimated.

Data Volumes and Performance Considerations

A Master Data Hub can manage millions and even billions of records. The cost of the hardware depends on these volumes and a variety of performance requirements, such as average transaction rates for reads, writes, and peak transaction rates. The number of physical servers, disc space, and other hardware components needed to support all of the required architectural tiers and components of the solution depends on the data volumes, transactional rates, and availability requirements. This can drastically impact the hardware cost.

Even more importantly, the MDM Data Hub license costs typically depend on the number of records that will be stored in or processed by the Data Hub. The number of records in the Data Hub grows over time. This roadmap view should reflect this consideration to determine how the hardware configuration and price will change over time, and to develop a recommendation and a cost mitigation strategy to establish a vendor agreement that supports an enterprise-acceptable pricing structure.

Reference Data

A typical list of master data domains includes Party, Product, Location, Supplier, Account, Organization, and other entities that may contain many thousands of records.

Each of these domains may include informational attributes (account value, customer credit score, and so on) and reference attributes. For the most part, reference data is represented by relatively static codes created and managed by the enterprise. These codes are important characteristics of master entities. From the application perspective, these codes are found in the lookup tables or displayed in drop-down menus for users to select, or are referenced in some other ways. For instance, accounts managed by the enterprise are characterized by account type. Products are tagged by class, category, type, and brand. Customers can be categorized by marketing segment, category, classification, gender, country of citizenship, and so on. Reference lists are defined and managed, and their codes reconciled for consistent use by the data governance team and the business owners of the data. Reference data reconciliation is an important problem that must be addressed as part of an MDM initiative. Reference code reconciliation can be approached as a work stream of an MDM program or managed as a separate project. Reference data may or may not be managed by the same software as master data. To sum up, if reference data is a part of the MDM program, it is an important view of the MDM roadmap that impacts the MDM initiative’s cost.

Deployment Strategy

This roadmap view defines what users will be impacted by the new processes and applications enabled by MDM, as well as when and how.

Significant user acceptance risks are associated with MDM deployment. For instance, bank tellers or customer support representatives may not be involved early enough in the MDM process. When the business process changes, the end users may be taken by surprise and learn that every time they intend to create a new customer they have to search the Data Hub first. They may also be instructed that every time they speak with a customer they have to verify certain pieces of information and that their performance will be measured by how well they perform these data quality functions.

This type of change, its timing, and user training should be well thought out and properly orchestrated. When end users are impacted, it may be a good idea to deploy the MDM solution for a small but representative group of users first. This partial deployment can represent a challenge, though. It may not be easy to deploy the new solution to some end users while still keeping the other users on the old system and business processes. Thus, deployment is an important view of an MDM roadmap.

Related Initiatives

Some enterprise-wide and even business-specific initiatives can be dependent on MDM. Conversely, the MDM program can be dependent on some other initiatives. These dependencies can represent significant risks and must be addressed by the MDM roadmap.

Some of the related efforts may include:

• A data warehouse project

• Client and Product Hierarchy Management

• CRM initiative

• SOA infrastructure

• Reference Data Management

• Core Banking System

• Trust Accounting System

• Patient Registration System

• Claim Processing System

Each enterprise has its own portfolio of projects that may or may not include some of the projects from this list. This portfolio should be reviewed from the MDM roadmap perspective. A project dependency review can drive changes in MDM planning and impact the vision of MDM priorities. The MDM roadmap document must include a discussion of the key related initiatives, the nature of the dependencies, and how they will be addressed.

Master Data Governance Maturity

Enterprise MDM is built for the benefit of multiple lines of business and therefore has a cross-functional context. An enterprise data governance organization typically represents cross-functional business requirements and brings them to a common set of standards and controls. The maturity of the data governance organization is critical for a successful MDM implementation; in fact, some practitioners call MDM and data governance “siblings.”

If the data governance organization is not mature, the absence of data governance policies and a lack of data governance support can increase risks and cause additional costs of the MDM implementation. If the individuals responsible for the MDM program implementation identify weaknesses in data governance, they should ensure that the MDM roadmap includes proper support and evolution of the data governance capabilities required to enable MDM, develop and socialize master data policies, establish a properly functioning data governance council, and define master data quality processes and controls (a detail discussion on data governance is offered in Chapter 17).

Master Data Quality Processes, Metrics, and Technology Support

Whether an MDM initiative has an operational or an analytical focus, master data quality processes are to be established and data quality metrics are to be introduced and continuously measured. These processes must be established by the business and the data governance group.

Master data quality processes, metrics, and technologies supporting these processes and metrics (for example, via a data governance dashboard) should be included in the MDM roadmap as one of its views (see Chapter 17 for a further discussion of MDM and data quality).

Integration with Unstructured Data

A vast majority of MDM initiatives do not include integration with the systems managing unstructured data. The unstructured data includes images, contracts, memos, documents, Microsoft Excel spreadsheets, and similar data. Some industry-specific MDM variants are integrated with unstructured data. For example, EMPI (Enterprise Master Patient Index) implementations, which represent a hospital or medical center variant of MDM, normally include integration of the MDM Data Hub with patients’ test results, images produced by X-rays, CT scans, MRI data, and other imaging technologies. This integration is accomplished by a cross-reference between EMPI and the indexes referencing documents, tests, and images. Similarly, pharmaceutical companies are interested in cross-references between the products the company is developing or has developed and the tremendous amount of unstructured data accumulated over the years of laboratory experiments.

Other industries can also benefit from integration between MDM and document management systems. For instance, a mortgage company can benefit from MDM integration with loan contracts and other documents associated with the loan. An enterprise embarking on an MDM initiative should consider the benefits and costs associated with the inclusion of unstructured data in the scope of MDM integration.

If, after careful consideration, an enterprise makes a decision to include integration between MDM and document management systems in the scope of MDM, this integration becomes an important MDM roadmap view.

Multilingual Requirements

So far, the majority of Master Data Management products have been developed in North America, and English is the predominant language these MDM products use. When MDM is implemented in an environment where another language is important, this roadmap view helps understand and estimate the impact of this challenge. The multiple-language–support requirement may result in additional costs and risks of the MDM implementation.

On global MDM projects, multiple languages are used within a single program. This may also apply to bilingual countries such as Canada. A number of areas of complexity are caused by multilingual requirements in MDM. Some of them include the following:

• Matching of records in different languages.

• By default, the majority of MDM products’ phonetic functions work only for English and possibly a few other languages.

• The same applies to the list of equivalencies. For instance, Rob is a likely nickname for Robert, and Bill for William. The Data Hub libraries contain the lists of equivalencies in English. The most established libraries may not include similar equivalency libraries in Russian, Chinese, or Korean.

• Address information is commonly used for matching. The accuracy of matching algorithms and address standardization algorithms can significantly depend on the language and local country standards and customs.

• The use of multiple character sets can create additional complications.

• Oftentimes reference data is altered from one language to another.

Complexity of Cross-Domain Information Sharing

Most MDM implementations are built using a single Data Hub that cross-references the records loaded from multiple source systems. In a number of scenarios, all records cannot be placed in a single database, and even the creation and maintenance of a single index that cross-references all records may not be an option. For instance, when MDM is implemented for multiple countries, country-specific regulations may prevent the storage and processing of their country data in databases maintained in other countries. Similarly, different branches of government are not allowed to store their data in systems managed by other organizations or agencies. Healthcare (patient) information cannot be placed in the same database as social security information.

Even when formally defined regulations do not exist, operational realities and risks associated with the placement of data managed by multiple agencies in a single database (MDM Data Hub) can be significant. This drives nontraditional MDM designs with multiple Data Hubs. These designs may rely on dynamic cross–Data Hub processes and information exchanges. These types of nontraditional implementations represent additional challenges that may result in extra costs. The MDM management team should be able to recognize and articulate requirements for multiple regulatory rules and regulations that restrict data sharing and the storage of data from multiple domains in a single Data Hub.

Complexity of Data Security, Visibility, and Access Control Requirements

Most MDM Data Hubs contain sensitive, private, or confidential information about enterprise business, customers, and products. Therefore, an extensive set of data security, visibility, and access control requirements is applicable to the majority of MDM Data Hub implementations. It is a common practice that an MDM Data Hub must support role-based, policy-driven secured access to data and independent audit capabilities.

For some MDM implementations, data security, visibility, and access control requirements are more stringent than for others. For instance, for wealth management organizations, multiple teams of financial advisors operate under the umbrella of a single financial services company. The majority of corporate and independent financial advisors serve their clients with only limited data sharing, as required by the nature of this business. Advanced needs for data security and visibility in these organizations create significant complexities that become a factor driving the complexity of the MDM program overall and the initiative’s cost. We offered an extensive discussion on data security and visibility in MDM environments in Part III of this book.

Resources and Skills

We will list typical work streams of an MDM initiative in Chapter 13. Each MDM program should define these work streams early in the life cycle of the initiative. It is important to follow the principle that one and only one individual should be responsible for a work stream to ensure accountability for planning and execution purposes. The role of program management is to follow and resolve inter–work stream dependencies and conflicting priorities.

Each of the work streams should be staffed with the right resource levels and skills. It may make a significant cost difference whether these skills are available in-house or should be filled with temporary employees or consultants.

Data governance is one of the often underestimated work streams. The data governance organization leads the work stream that includes data stewardship resources. The data governance work stream is responsible for the definition of data stewardship needs, data stewardship responsibilities, and other requirements that drive the number of data stewards, their activities, their functions, and the incremental costs.

Testing is another work stream that has been often underestimated on large MDM initiatives. Testing for an MDM Data Hub project requires skills that go beyond the traditional testing of application logic. MDM Data Hub testing may require comprehensive data testing and Web Services testing skills.

Enabling Technologies: ETL, SOA, and ESB

If MDM requires real-time or near-real-time integration with operational systems, the attention to and reliance on service-oriented architecture and technologies such as SOA infrastructure and Enterprise Service Bus (ESB) is very important. These technologies can significantly facilitate an MDM implementation from the integration perspective. On the other hand, the absence of a real-time integration infrastructure can become a considerable impediment for an MDM program.

Similar considerations apply to data quality technologies and ETL. Most companies embarking on MDM had previously acquired ETL and some data quality software. If this assumption does not hold, it is important to consider these technologies and their integration in the scope of MDM.

Conclusion

To sum up, in this chapter we discussed two related topics:

• MDM business case and justification of MDM

• Development of an MDM roadmap

We started with a discussion of the importance of the business case for MDM, as well as its challenges, methods, and techniques that can be used for MDM justification. Then we focused on the importance of the MDM roadmap. We explained why the MDM business case and roadmap should be considered together. The MDM roadmap defines the evolution of MDM and critical architectural and organizational decisions that impact the MDM initiative’s cost, risk, risk mitigation strategies, and ultimately the ROI and NPV.

We have identified and described 20 critical MDM roadmap views. Each of these views should be considered at the inception, when an MDM initiative is planned, and then reviewed periodically as the program evolves. The 20 MDM roadmap views provide a fairly comprehensive framework of the most critical MDM areas. A periodic review of the critical MDM roadmap views and their refinement can help significantly to properly initiate and execute MDM programs. Clearly, the relative importance of the roadmap views varies from one MDM initiative to another. Even within a single MDM program, the relative importance of the roadmap views can change as the program evolves.

We will continue our discussion of key MDM implementation aspects in the subsequent chapters.

References

1. Page, Rick. Hope is Not a Strategy: The 6 Keys to Winning the Complex Sale. (March 2003).

2. Karel, Rob. “The ROI for Master Data Management.” Forrester Research, Inc., October 29, 2008. (Available online from Forrester Research, Inc.)

3. Linthicum, David. “Defining the ROI for Data Integration.” http://blogs.informatica.com/perspectives/index.php/2009/09/23/defining-the-roi-for-data-integration/.

4. Jones, Nathan. “20 Reasons for Data Quality in Charts of Accounts and Internal Organisation.” Information and Decisions, December 16, 2009. http://nathanjones.wordpress.com/2009/12/16/20-reasons-for-data-quality-in-charts-of-accounts-and-internal-organisation/.

5. Liliendahl Sorensen, Henrik. “55 Reasons to Improve Data Quality.” Liliendahl on Data Quality, http://liliendahl.wordpress.com/2009/11/22/55-reasons-to-improve-data-quality/.

6. Africa, Andrew. “Rely on Data Quality to Survive.” InfoManagement Direct, August 20, 2009. http://www.information-management.com/infodirect/2009_135/data_quality_economy_it_business_intelligence_bi-10015920-1.html?ET=informatio nmgmt:e1080:2188289a:&st=email.

7. Joshi, Nitin. “Quantifying Business Value in Master Data Management.” InfoManagement Direct, September 3, 2009. http://www.information-management.com/infodirect/2009_137/master_data_management-10016016-1.html.

8. Jones, Dylan. “Using Metrics to Assert a Business Case for Data Quality.” Data Quality Pro, November 2009. http://www.dataqualitypro.com/data-quality-home/using-metrics-to-assert-a-business-case-for-data-quality.html.

9. Berson, Alex, Smith, Stephen, and Thearling, Kurt. Building Data Mining Applications for CRM. McGraw-Hill (December 1999).

10. Hillard, Robert and Sean McClowry. “Economic Value of Information.” Mike 2.0. http://mike2.openmethodology.org/wiki/Economic_Value_of_Information.

11. Loshin, David. Master Data Management. The MK/OMG Press (September 2008).

12. Dubov, Lawrence. “Estimating the Benefits for MDM.” Mastering Data Management, February 23, 2010. http://blog.initiate.com/index.php/2010/02/23/estimating-the-benefits-of-mdm/.

13. Dubov, Lawrence. “Master Data Management: Importance of Relationship Management.” Information Management, March 19, 2009. http://www.information-management.com/specialreports/2009_132/10015070-1.html.TMCNet.com, April 8, 2009. http://callcenterinfo.tmcnet.com/Analysis/articles/53858-master-data-management-importance-relationship-management.htm.

14. Linthicum, David. “The Importance of Relationship Management with MDM.” Ebiz, April 16, 2009. http://www.ebizq.net/blogs/linthicum/2009/04/the_ importance_of_relationship.php.

15. Isler, Adam. “MDM and Relationship Linking.” Intelligent Database Marketing, March 25, 2009. http://pntblog.com/2009/03/25/mdm-and-relationship-linking/.

16. Dubov, Lawrence. Series: Building and MDM Roadmap. April 13, 2010. http://blog.initiate.com/index.php/2010/04/13/series-building-an-mdm-roadmap/.