CHAPTER 8

Overview of Risk Management for Master Data

In business, we recognize and are concerned about various types of risks, including financial, legal, operational, transactional, reputational, and many others. While these types of risks don’t represent formal risk taxonomy, it is easy to see that they all have some elements in common and are closely related. Unfortunately, more often than not various risk types are treated differently by different organizations within the enterprise, often without proper coordination between the organizations and without the ability to effectively recognize and aggregate the risks to understand the root causes and thus the most effective approaches to mitigate the risks.

This chapter offers a high-level overview of various types of risk, risk management strategies, and the implications of the major risk types for Master Data Management across various data domains. It is not intended to provide readers with a complete set of definitions, processes, and concerns of the integrated risk management and regulatory impact analysis. Rather, the goal of this chapter is to help information technology teams and MDM designers to be aware of the concerns and high-level requirements of the integrated risk management. This awareness should help MDM practitioners to better understand the impact of integrated risk management on the architecture, design, and implementation of Master Data Management solutions.

Risk Taxonomy

The interconnected nature of various risk types became highly visible with the emergence of a broad set of government regulations and standards that focus on increased information security threats related to criminal and terrorist activities that can result in unintended and unauthorized information exposure and security compromise. The types of risks companies are facing include:

• Transaction risk Sometimes also referred to as operational risk, transaction risk is the primary risk associated with business processing. Transaction risk may arise from fraud, error, or the inability to deliver products or services, maintain a competitive position, or manage information. It exists in each process involved in the delivery of products or services. Transaction risk includes not only production operations and transaction processing, but also areas such as customer service, systems development and support, internal control processes, and capacity planning. Transaction risk may affect other risk types such as credit, interest rate, compliance, liquidity, price, strategic, and reputational risks.

• Reputational risk Errors, delays, omissions, and information security breaches that become public knowledge or directly affect customers can significantly impact the reputation of the business. For example, a failure to maintain adequate business resumption plans and facilities for key processes may impair the ability of the business to provide critical services to its customers.

• Strategic risk Inaccurate or incomplete information can cause the management of an organization to make poor strategic decisions. We will focus on this type of risk in Part IV when discussing data quality and the methods to improve it.

• Compliance (legal) risk Inaccurate or untimely data related to consumer compliance disclosures or unauthorized disclosure of confidential, material non-public information (MNPI) about the business transaction or personally identifiable customer information could expose an organization to significant financial penalties and even costly litigation. Failure to track regulatory changes and provide timely accurate reporting could increase compliance risk for any organization that acquires, manages, and uses customer data.

NOTE There are other ways to represent various types of risks. We will discuss a different representation of the risk taxonomy later in this chapter, when we review how the emerging regulatory and compliance requirements are driving risk management approaches.

To address these various risks, companies have to develop and maintain a holistic risk management program that coordinates various risk management activities for a common goal of protecting the company and its assets.

Using these definitions, an organization can calculate the risk if it understands the possibility that a vulnerability will exist, the probability that a threat agent will exploit it, and the resulting cost to the company. In practical terms, the first two components of this equation can be analyzed and understood with a certain degree of accuracy. The cost component, on the other hand, is not always easy to figure out since it depends on many factors, including business environments, markets, competitive positioning of the company, and so on. Clearly, not having a cost component makes the calculation of the risk management ROI a challenging proposition. For example, in the case of the risk of a computer virus attack, one option to calculate the cost could be based on how many computers have to be protected using appropriate antivirus software—the total cost will include the costs of software licenses, antivirus software administration, configuration and distribution/deployment, and software patch management. The other option could be to calculate the cost based on the assumption that infected computer systems prevent the company from serving their customers for an extended period of time, let’s say one business day. In that case, the cost could be significantly larger than the one assumed in the first option.

Furthermore, consider the risk of a computer system theft or a data compromise. The resulting potential exposure and loss of customer data may have significant cost implications, and the cost to the company could vary drastically from a reasonable system recovery expense to the hard-to-calculate cost of potentially irreparable damage to the company’s reputation. Combining this cost with the cost of a highly probable case of litigation against the company, this risk can result in loss of potential and unrealized customer revenue, loss of market share and, in the extreme case, even liquidation of the business.

The implication of the definitions shown above is clear: To manage the risks properly, the company must understand all of its vulnerabilities and match them to specific threats. This can be accomplished by employing any formal risk management methodology and a formal risk management process that at a minimum includes the following four steps:

1. Identify the assets and their relative value.

2. Define specific threats and the frequency and impact that would result from each occurrence.

3. Calculate annualized loss expectancy (ALE).

4. Prioritize risk reduction measures and select appropriate safeguards.

This high-level process allows an organization to be in a position to define a risk management strategy that includes options to either find a way to avoid the risk, accept the risk, transfer the risk (for example, by purchasing the insurance), or mitigate the risk by identifying and applying the necessary actions (known as “countermeasures”).

While a comprehensive discussion of risk management and various types of risks is well beyond the scope of this book, understanding and managing information security risks by defining appropriate countermeasures is key to designing and deploying Master Data Management solutions, especially MDM Data Hub solutions that deal with customer information. Therefore, we will discuss the notion of customer-level risks, the causes of information security risks, regulatory and compliance drivers that elevate the concerns of the information security risks to the highest levels of the organization, and the principles used to develop information risk management strategies.

Regulatory Compliance Landscape

Businesses in general, and financial services firms in particular, are beginning to recognize and adopt the concept of Integrated Risk Management (IRM) as a means to manage the complex process of identifying, assessing, measuring, monitoring, and mitigating the full range of risks they face. One of the drivers for IRM is the expansion of the traditional risk management scope to include the notion of “customer risk” for individual and institutional customers alike—a notion that, in addition to the already-familiar personal credit risk and probability of default, now includes the risks of fraudulent and terrorism-related behavior, the risk of exposing confidential personal and business-related information and violating customer privacy, as well as the risk of customer identity theft. Many of these customer-level risk concerns have become significantly more visible and important as organizations have started to integrate and aggregate all information about their customers using advanced MDM solutions.

The reason for this elevated level of concerns is straightforward: Customer privacy and protection of personally identifiable customer information, protection of material non-public information (MNPI), and concerns related to information confidentiality and integrity have become subject to new regulatory and compliance legislations and industry-wide rules. In many cases, compliance is mandatory, with well-publicized implementation deadlines. Depending on a particular regulation and legal interpretation, noncompliance may result in stiff penalties, expensive litigation, damaged reputation, and even an inability to conduct business in certain markets. To achieve timely compliance, to manage these and other types of risks in a cohesive, integrated fashion, companies around the world are adopting technology, data structures, analytical models, and processes that are focused on delivering effective, integrated, enterprise-wide risk management solutions. But the technology is just an enabler of IRM. IRM cannot be implemented without the direct participation of the business units. For example, the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC) is forcing financial organizations to place risk management directly at the business unit level. These IRM-related regulations are forcing companies to ensure that the business managers own and manage risk. This approach results in integrated risk management solutions that provide a single, cohesive picture of risk exposure across the entire organization.

Integrated Risk Management: Benefits and Challenges

An effective information risk management strategy provides improved accuracy for risk and compliance reporting, and can mitigate transaction risk by reducing operational failures. Some of the benefits of an integrated information risk management strategy are shown in the following list:

• The ability to provide accurate, verifiable, and consistent information to internal and external users and application systems.

• The ability to satisfy compliance requirements using clean, reliable, secure, and consistent data.

• The ability to mitigate transaction risk associated with the data issues. For example, in financial services, companies embarked on implementing IRM strategies are better positioned to avoid data-related issues that affect the successful implementation of Straight Through Processing and next-day settlement environments (STP and T+1).

• Flexibility in implementing and managing new organizational structures and the cross-organizational relationships that can be caused by the increase in the Merger and Acquisition (M&A) activities as well as in forming new partnerships.

• The ability to define, implement, and measure enterprise-wide data governance and quality strategy and metrics.

• The ability to avoid delays related to data issues when delivering new products and services to market.

Many organizations struggle when attempting to implement a comprehensive and effective information risk management strategy, often because they underestimate the complexity of the related business and technical challenges. Moreover, these risks and challenges have to be addressed in the context of delivering integrated master data solutions such as those enabled by MDM platforms. Some of these challenges include:

• Business Challenges

• Some risk management and information strategy solutions may have a profound impact on the organization at large, and thus may require continuous executive-level sponsorship.

• Data ownership and stewardship have organizational and political implications that need to be addressed prior to engaging in implementation of the information risk management strategy.

• Determining real costs and calculating key business metrics such as Return on Investment (ROI), Return on Equity (ROE), and Total Cost of Ownership (TCO) is difficult; the calculations are often based on questionable assumptions and thus produce inaccurate results and create political and budgetary challenges.

• New regulatory requirements introduce additional complexity into the process of defining and understanding intra- and inter-enterprise relationships; this is one of the areas where Master Data Management can help mitigate the complexity risks.

• The product and vendor landscape is changing rapidly. Although technology solutions continue to mature, this causes additional uncertainty and increases the risk of not achieving successful, on-time, and on-budget project delivery.

• Global enterprises and international business units often face conflicting regulatory requirements, cross-border data transfer restrictions, and various local regulations pertaining to outsourcing and off-shoring data that include access, content masking, storage, and transfer components.

• Technical Challenges

• Risk management solutions must be scalable, reliable, flexible, and manageable. This challenge is particularly important for financial services institutions with their need to support the enterprise-level high throughput required for the high-value global transactions that traverse front-office and back-office business systems (for example, globally distributed equities or currency trading desks).

• Risk-related data already resides in a variety of internal repositories, including enterprise data warehouses and CRM data marts, but its quality and semantic consistency (different data models and metadata definitions) may be unsuitable for business transaction processing and regulatory reporting.

• Similarly, risk-related data is acquired from a variety of internal and external data sources that often contain inconsistent or stale data.

• Risk data models are complex and are subject to new regulations and frequently changing relationships between the organizations and its customers and partners.

• Even business-unit—specific risks can have a cascading effect throughout the enterprise, and risk mitigation strategies and solutions should be able to adapt to rapidly changing areas of risk impact. Specifically, a business unit (BU) may be willing to accept a particular risk. However, a security compromise may impact the company brand name and reputation well beyond the scope of a particular channel or a business unit. For example, a major bank may have tens of business units. A security breach within a mortgage BU can affect retail sales, banking, wealth management, consumer lending, credit card services, auto finance, and many other units.

All these challenges have broad applicability to all enterprise-class data management issues, but they are particularly important to organizations that embark on implementing MDM solutions.

Regulatory Compliance Requirements and Their Impact on MDM IT Infrastructure

As we stated in previous sections, a number of new regulatory and compliance legislations have become the primary drivers for the emergence and adoption of the Integrated Risk Management concept. Generally speaking, access to and use of any information that is classified as restricted, confidential, or private needs to be regulated and controlled, and a number of broadly defined regulations address these controls. The situation becomes even more critical when we consider two industry segments that by definition have to deal with a customer’s privacy and confidentiality concerns by protecting personally identifiable information (PII): financial services and healthcare. In this case, regulations that are focused on protecting customer financial and personally identifiable data, as well as the risks associated with its misuse, include but are not limited to the following:

• The Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002 (SOX) defines requirements for the integrity of the financial data and availability of appropriate security controls.

• The USA Patriot Act includes provisions for Anti-Money Laundering (AML) and Know Your Customer (KYC).

• The Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act (GLBA) mandates strong protection of personal financial information through its data protection provisions.

• The Basel II and Basel III Capital Requirements define various requirements for operational and credit risks.

• FFIEC guidelines require strong authentication to prevent fraud in banking transactions.

• The Payment Card Industry (PCI) Standard defines the requirement for protecting sensitive cardholder data inside payment networks.

• California’s SB1386 is a state regulation requiring public written disclosure in situations when a customer file has been compromised.

• Do-Not-Call and other opt-out preference requirements protect customers’ privacy.

• International Accounting Standards Reporting IAS2005 defines a single, high-quality international financial reporting framework.

• The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) places liability on anyone who fails to properly protect patient health information including bills and health-related financial information.

• New York Reg. 173 mandates the active encryption of sensitive financial information sent over the Internet.

• Homeland Security Information Sharing Act (HSISA, H.R. 4598) prohibits public disclosure of certain information.

• The ISO 17799 Standard defines an extensive approach to achieve information security including communications systems requirements for information handling and risk reduction.

• The European Union Data Protection Directive mandates the protection of personal data.

• Japanese Protection for Personal Information Act.

• Federal Trade Commission, 16 CFR Part 314 defines standards for safeguarding customer information.

• SEC Final Rule, Privacy of Consumer Financial Information (Regulation S-P), 17 CFR Part 248 RIN 3235-AH90.

• OCC 2001-47 defines third-party data-sharing protection.

• 17 CFR Part 210 defines rules for records retention.

• 21 CFR Part 11 (SEC and FDA regulations) define rules, for electronic records and electronic signatures.

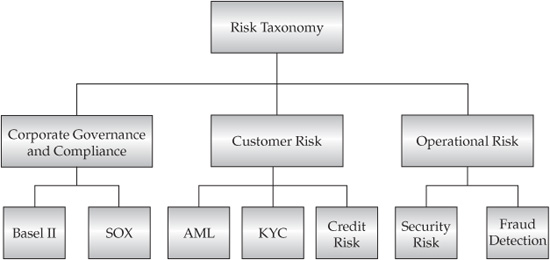

FIGURE 8-1 Risk taxonomy

• NASD rules 2711 and 3010 define several supervisory rules, including the requirement that each member establish and maintain a system to supervise the activities of each registered representative and associated person.

This is far from a complete list, and it continues to grow and expand its coverage and impact on the way businesses must conduct themselves and protect their customers.

Many of these regulations are “connected” to each other by their risk concerns and the significant implications for the IT infrastructure and processes that are required to comply with the applicable laws. If we were to map the types of risks discussed in this chapter to the key regulations that are designed to protect the enterprise and its customers from them, we might end up with the mapping shown in Figure 8-1.

Using this risk taxonomy diagram as a guide, the following sections discuss some of the regulatory compliance requirements and their impact on the information management infrastructures.

The Sarbanes-Oxley Act

The Sarbanes-Oxley Act (SOX) addresses a set of business risk management concerns and contains a number of sections defining specific reporting and compliance requirements.3

Some of the key requirements of the Act are defined in Sections 302, 404, 409, and 906, and they require that the company’s CEO/CFO must prepare quarterly and annual certifications that attest that:

• The CEO/CFO has reviewed the report.

• The report does not contain any untrue or misleading statement of a material fact or omit to state a material fact.

• Financial statements and other financial information fairly present the financial condition.

• The CEO/CFO is responsible for establishing and maintaining disclosure controls and has performed an evaluation of such controls and procedures at the end of the period covered by the report.

• The report, discloses to the company’s audit committee and external auditors:

• Any significant deficiencies and material weaknesses in Internal Control over Financial Reporting (ICFR)

• Any fraud that involves personnel that have a significant role in the company’s ICFR SOX, requires each annual report to contain an “internal control report” that:

• Defines management’s responsibilities for establishing and maintaining ICFR

• Specifies the framework used to evaluate ICFR

• Contains management’s assessment of ICFR as of the end of the company’s fiscal year

• States that the company’s external auditor has issued an attestation report on management’s assessment

SOX also requires that:

• The company’s external auditor reports on management’s internal control assessment.

• Companies have to take certain actions in the event of changes in controls.

In addition, Section 409 specifies the real-time disclosure requirements that need to be implemented by every organization. This represents a challenge for those companies that have predominantly offline, batch business reporting processes.

The events requiring real-time disclosure include:

• Loss of major client (bundled service purchaser or significant component of product portfolio)

• Increased exposure to industries that are “in trouble” (significant portion of portfolio)

• Impact of external party changes (for example, regulators, auditors)

• Write-offs of a significant number of loans or portfolios

• Cost over-runs on IT or other major capital projects

These and similar material events will require reporting to interested parties within 48 hours of the event’s occurrence. From a technical capabilities point of view, Section 409’s real-time disclosure requires:

• Real-time analytics instead of or in addition to batch reporting

• The ability to report on a wide range of events within 48 hours

• Real-time notification and event-driven alerts

• Deep integration of information assets

Clearly, achieving SOX compliance, and especially compliance with Section 409 requirements, would be easier using an MDM solution to provide flexible and scalable near-real-time reporting capabilities.

Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act Data Protection Provisions

The Gramm-Leach-Bliley Financial Modernization Act was signed into law on November 11, 1999 as Public Law 106-102.4 The GLBA contains a number of sections and provisions that specify various data protection requirements, including protection of nonpublic personal information, obligations with respect to disclosures of personal information, disclosure of institution’s privacy policy, and a number of other related requirements.5

Of particular interest to the preceding discussion is GLBA Section 501, which is focused on establishing standards for protecting the security and confidentiality of financial institution customers’ nonpublic personal information. Specifically, GLBA Section 5016 defines the Data Protection Rule and subsequent safeguards that are designed to:

• Ensure the security and confidentiality of customer data

• Protect against any reasonably anticipated threats or hazards to the security or integrity of the data

• Protect against unauthorized access to or use of such data that would result in substantial harm or inconvenience to any customer

GLBA key privacy protection tenets are defined in the following paragraphs:

• Paragraph A “Privacy obligation policy-It is the policy of the Congress that each financial institution has an affirmative and continuing obligation to respect the privacy of its customers and to protect the security and confidentiality of those customers’ nonpublic personal information.”

• Paragraph B3 “… to protect against unauthorized access to or use of such records or information which could result in substantial harm or inconvenience to any customer.”

In the context of GLBA, the term "nonpublic personal information" (NPI) referenced in Paragraph A means personally identifiable information (PII) that is

• Provided by a customer to a financial institution,

• Derived from any transaction with the customer or any service performed for the customer, or

• Obtained by the financial institution via other means.

In January 2003, the Federal Financial Institutions Examination Council (FFIEC) issued new guidance that expanded GLBA. The new guidance requires financial institutions to protect all information assets, not just customer information. The FFIEC recommended a security process that the financial institutions have to put in place to stay compliant with the expanded requirements. This process includes the following components:

• Information security risk assessment including employee background checks

• Security strategy development including:

• Response programs for unauthorized events

• Protective measures against potential environmental hazards or technological failures

• Implementation of security controls (these controls and technologies enabling the controls are discussed in some detail in Chapters 9–11):

• Access controls and restrictions to authenticate and permit access by authorized users only

• Encryption of data-in-transit (on the network) and data-at-rest (on a storage device)

• Change control procedures

• Security testing

• Continuous monitoring and updating of the security process, including monitoring systems and procedures for intrusion detection

GLBA makes an organization responsible for noncompliance even if the security breach and the resulting data privacy violation are caused by an outside vendor or service provider.

Specifically, according to GLBA, the organization must establish appropriate oversight programs of its vendor relationships, including:

• Assessment of outsourcing risks to determine which products and services are best outsourced and which should be handled in-house

• Creation and maintenance of an inventory list of each vendor relationship and its information the vendor can access

• Routine execution of proper due diligence of third-party vendors

• Execution of written contracts that outline duties, obligations, and responsibilities of all parties

A number of federal and state agencies are involved in enforcing GLBA, for example:

• Federal banking agencies (that is, Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, Comptroller of the Currency, FDIC, Office of Thrift Supervision, and others)

• National Credit Union Administration

• Secretary of the Treasury

• Securities and Exchange Commission

• Federal Trade Commission

• National Association of Insurance Commissioners

It is easy to see that the requirements imposed by the Sarbanes-Oxley and Gramm-Leach-Bliley acts have clear implications for the way organizations handle customer and financial data in general and, by extension, how the data is managed and protected in data integration platforms such as Master Data Management systems.

Other Regulatory/Compliance Requirements

Of course, in addition to SOX and GLBA, there are numerous other regulations that have similarly profound implications for the processes, technology, architecture, and infrastructure of the enterprise data strategy and particularly on the initiatives to develop MDM solutions. We’ll discuss some of these regulations briefly in this section for the purpose of completeness.

OCC 2001-47

GLBA makes an organization responsible for noncompliance even if the breach in security and data privacy is caused by an outside vendor or service provider. Specifically, the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC) has defined the following far-reaching rules that affect any institution that plans to share sensitive data with an unaffiliated third party:

• A financial institution must take appropriate steps to protect information that it provides to a service provider, regardless of who the service provider is or how the service provider obtains access.

• The Office of the Comptroller of the Currency defines oversight and compliance requirements that require company management to:

• Engage in a rigorous analytical process to identify, measure, monitor, and establish controls to manage the risks associated with third-party relationships.

• Avoid excessive risk-taking that may threaten the safety and integrity of the company.

The OCC oversight includes a review of the company’s information security and privacy protection programs regardless of whether the activity is conducted directly by the company or by a third party. OCC’s primary supervisory concern in reviewing third-party relationships is whether the company is assuming more risk than it can identify, monitor, manage, and control.

USA Patriot Act: Anti-Money Laundering (AML) and Know Your Customer (KYC) Provisions

Money laundering has become a serious economic and political issue. Indeed, the International Monetary Fund has estimated that the global proceeds of money laundering could total between 2 and 5 percent of the world gross domestic product, which is equivalent to 1 to 3 trillion USD every year.

The USA Patriot Act is one of a number of legislations that deal with issues of money laundering. The long list of related legislations includes the 1970 Bank Secrecy Act (BSA), the 1986 Money Laundering Control Act, the 1988 Money Laundering Prosecution Improvement Act, and the 1990 Bank Fraud Prosecution and Taxpayer Recovery Act of 1990 (Crime Control Act), to name just a few.

The USA Patriot Act of 2001 is an abbreviation of the 2001 law with the full name "Uniting and Strengthening America by Providing Appropriate Tools to Restrict, Intercept and Obstruct Terrorism Act." It requires information sharing among the government and financial institutions, implementation of programs that are concerned with verification of customer identity, implementation of enhanced due-diligence programs; and implementation of anti-money laundering programs across the financial services industry7

With the advent of the International Money Laundering Abatement and Anti-Terrorism Financing Act of 2001 (Title 3 of the USA Patriot Act), the U.S. Department of the Treasury has enacted far-reaching regulations aimed at detecting and deterring money-laundering activities and events. These regulations apply to all financial institutions, and have direct implications for all Master Data Management initiatives as activities that deal with the totality of customer financial and personal information.

The USA Patriot Act affects all financial institutions, including banks, broker-dealers, hedge funds, money service businesses, and wire transfers, by requiring them to demonstrate greater vigilance in detecting and preventing money-laundering activity. It defines implementation milestones that include mandatory suspicious activity reporting (SAR) and mandatory adoption of due-diligence procedures to comply with these regulations.

USA Patriot Act Technology Impact Business process requirements of the USA Patriot Act include:

• Development of the AML policies and procedures.

• Designation of a compliance officer.

• Establishment of a training program.

• Establishment of a corporate testing/audit function.

• Business units that manage private banking accounts held by noncitizens must identify owners and sources of funds.

• For the correspondent accounts processing, implement restrictions that do not allow account establishment with foreign shell banks; implement strict and timely reporting procedures for all corresponding accounts with a foreign bank.

• Organizations must develop and use “reasonable procedures” to know their customer when opening and maintaining accounts.

• Financial institutions can share information on potential money-laundering activity with other institutions to facilitate government action; this cooperation will be immune from privacy and secrecy-based litigations.

The USA Patriot Act requires banks to check a terrorist list provided by the Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN). Another list to be checked is provided by the Treasury’s Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC). Additional information sources may become available as the system matures.

Key technical capabilities that support the USA Patriot Act requirements include:

• Workflow tools to facilitate efficient compliance procedures, including workflow processes to prioritize and route alerts to appropriate parties

• Analytical tools that support the ongoing detection of hidden relationships and transactions among high-risk entities, including the ability to detect patterns of activity to help identify entities utilizing the correspondent account (the customer’s customer)

• Creation and maintenance of account profiles and techniques like scenario libraries to help track and understand client behavior throughout the life of the account

• Support of risk-based user segmentation and a full audit trail to provide context for outside investigations

• Policy-driven comprehensive monitoring and reporting to provide a global view and to promote effective and timely decision making

Many of the required capabilities can be enabled by effective leveraging the data collected and maintained by the existing CRM or new MDM systems. However, the USA Patriot Act and its “Know Your Customer” (KYC) directive require additional customer-focused information.

This requirement of knowing your customers and being able to analyze their behavior quickly and accurately is one of the benefits and a potential application of the MDM for Customer Domain.

Basel II Capital Accord Technical Requirements

In 1988, the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision introduced a capital measurement system, commonly referred to as the Basel Capital Accord. This system addressed the design and implementation of a credit risk measurement framework for a minimum capital requirement standard. This framework has been adopted by more than a hundred countries.

In June 1999, the Committee issued a proposal for a New Capital Adequacy Framework to replace the 1988 Accord. Known as “Basel II,” this capital framework consists of three pillars8:

• Pillar I Minimum capital requirements

• Pillar II Supervisory review of an institution’s internal assessment process and capital adequacy

• Pillar III Effective use of disclosure to strengthen market discipline as a complement to supervisory efforts

One key departure from the 1988 Basel Accord is that banks are required to set aside capital for operational risk. The Basel Committee defines operational risk as “the risk of direct or indirect loss resulting from inadequate or failed internal processes.”

The Basel II Accord seeks to align risk and capital more closely, which may result in an increase in capital requirements for banks with higher-risk portfolios.

To comply with Basel II requirements financial institutions have begun creating an Operational Risk Framework and Management Structure. A key part of this structure is a set of facilities that would track and securely store loss events in Loss Data Warehouses (includes Loss, Default, and Delinquency data) so that at least two years of historical data are available for processing. A Loss Data Warehouse (LDW) is a primary vehicle to provide an accurate, up-to-date analysis of capital adequacy requirements, and is also a source of disclosure reporting.

In the context of Master Data Management, an LDW should become an integrated platform of accurate, timely, and authoritative data that can be used for analysis and reporting.

NOTE In December 2009, the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision published two consultative documents that have been widely considered as the foundation of a new “Basel III Accord” that is focused on the strengthening of the global banking system. At the time of this writing the work on defining specific Basel III requirements was ongoing.

FFIEC Compliance and Authentication Requirements

On October 12, 2005, the Federal Financial Institutions Examination Council (FFIEC) issued new guidance on customer authentication for online banking services. According to the FFIEC guidance, the authentication techniques employed by the financial institution should be appropriate to the risks associated with those products and services used by the authenticated users. The new regulation guides banks to apply two major methods:

• Risk assessment Banks must assess the risk of the various activities taking place on their Internet banking site.

• Risk-based authentication Banks must apply stronger authentication for high-risk transactions.

Technical implications of the FFIEC regulations include:

• The ability to provide multifactor authentication for high-risk transactions

• Monitoring and reporting capabilities embedded into all operational systems

• Appropriate strength of authentication that is based on the degree of risk

• Customer awareness and ability to provide reverse authentication where customers are assured they communicate with the right institution and not a fraudulent site

• Implementation of layered security framework

Let’s consider these requirements in the context of MDM. An MDM Data Hub solution designed and deployed by a financial institution will most likely represent the authoritative source of customer personal and financial data. Therefore, a Data Hub platform must be designed to support the adaptive authentication and information security framework required by the FFIEC regulations. Key details of this enterprise security framework are discussed in Chapter 11.

State Regulations: California’s SB1386

In addition to U.S. federal regulations, individual states have adopted various legislations that deal with data privacy and confidentiality. Among these state-level legislations, California’s Senate Bill 1386 (SB1386) was one of the first state laws on this topic, and we’ll briefly describe it in this section to illustrate the interdependencies between state and federal legislations.

SB1386 was introduced in 2002,9 and it requires that companies dealing with residents of the State of California disclose breaches of their computer systems, when such breaches are suspected of compromising certain confidential information of the California customers. The most unique feature of this law is that it allows for class-action lawsuits against companies in the event of noncompliance.

SB1386 and Sarbanes-Oxley Compliance In the beginning of this chapter we stated that many of the regulations affecting the processes and methods of information management are interconnected. This section describes one such example of the connected nature of the regulations.

The Committee of Sponsoring Organizations of the Treadway Commission (COSO) has established a framework10 against which a company’s internal controls may be benchmarked for effectiveness and compliance with the Sarbanes-Oxley Act and other applicable laws. According to the COSO framework, the companies are required to identify and analyze risks, establish a plan to mitigate each risk, and have well-defined policies and procedures to ensure that management objectives are achieved and risk mitigation strategies are executed.

The implication of these requirements is that failure to deal with regulations such as California SB1386 effectively could be interpreted as the failure of a company’s management in establishing and maintaining appropriate internal controls to deal with the risk of customer data compromise, thus violating the principal requirements of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act. Litigation and the resulting SB1386 judgments could potentially trigger Sarbanes-Oxley– related violations and its consequences.

Key Information Security Risks and Regulatory Concerns

The networked, interconnected, and global nature of today’s business and technology ecosphere has created incredible opportunities for organizations to increase their customer bases and market share, create new effective partnerships, improve their effectiveness and agility, rapidly introduce new products and services, and in general successfully grow their businesses. Likewise, customers are able to take full advantage of the interconnected, Internet-based channels, products, and services to become willing participants in this networked economy. However, the convenience and availability of the network-based products and services come with new complications and risks, including viruses, worms, and hackers of all types. These risks are growing and multiplying and are impacting not just individual customers but also business and government organizations (for example, widely publicized denial-of-service attacks and other acts of cyber-terrorism). The reality is such that the number of types of risks is growing faster than what security technologies can build countermeasures for.

This is an ever-growing area of concern for all risk management and law enforcement professionals globally, and the analysis of all types of information security risks is clearly beyond the scope of a single book. However, one area of this risk is directly connected to the privacy and information protection discussion in the previous sections, and it represents the fastest-growing white-collar crime: identity theft.

Identity Theft

Numerous government and private sector reports from sources such as the Federal Trade Commission (FTC), the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), and the Computer Security Institute (CSI) repeatedly indicate that identity theft is rapidly becoming one of the fastest-growing white-collar crimes on the Internet. According to the FBI, the number of Internet sites that spread various forms of “crimeware” designed to steal PC passwords reached an all-time high of 31,173 in December of 2008, an 827 percent increase from January of 2008.11

Even more disturbing, identity theft continues to be on the rise, and the size of the problem is becoming quite significant.

For example, according to the 2009 Gartner Report, about 7.5 percent of U.S. adults lost money to some sort of financial fraud in 2008, and data losses cost companies an average of $6.6 million per breach. The direct effect of the identify theft is that for the same time period, customer attrition across industry sectors due to a data breach almost doubled from the regular rate of 3.6 percent to 6.5 percent, and in the financial services sector in particular the turnover rate reached 5.5 percent.12 And the Identity Theft Statistics website13 offers the following disturbing facts:

• There were 10 million victims of identity theft in 2008 in the U.S. (Javelin Strategy and Research, 2009).

• One in every ten U.S. consumers has already been victimized by identity theft (Javelin Strategy and Research, 2009).

• Over a million households experienced fraud not related to credit cards (that is, their identity theft than those with salaries under $50,000 (U.S. Department of Justice, 2005).

• Those households with incomes higher than $70,000 were twice as likely to experience identity theft than those with salaries under $50,000 (U.S. Department of Justice, 2005).

• Seven percent of identity theft victims had their information stolen to commit medical identity theft.

There are two primary classes of economic crime related to identity theft:

• Account takeover occurs when a thief acquires a person’s existing credit or bank account information and uses the existing account to purchase products and services. Victims usually learn of account takeover when they receive their monthly account statement.

• In true identity theft, a thief uses another person’s SSN and other identifying information to fraudulently open new accounts and obtain financial gain. Victims may be unaware of the fraud for an extended period of time—which makes the situation that much worse.

In general, credit card fraud is the most common application of the account takeover style of identity theft, followed by phone or utility fraud, bank fraud, real estate rent fraud, and others.

Phishing and Pharming

Traditionally, the most common approach to stealing one’s identity was to somehow get hold of the potential victim’s personal information and confidential data such as passwords. In pre-Internet days thieves went after one’s wallet or a purse. Then they increased the area of “coverage” by collecting and analyzing the content of the trash of the intended victims. With the advent of electronic commerce, the Internet and the Web, the thieves embarked on easy-to-implement phishing scams, in which a thief known as a “phisher” takes advantage of the fact that some users trust their online establishments such as banks and retail stores. The phisher creates compelling e-mail messages that lead unaware users to disclose their personal data. For example, a frequent phishing scam is to send an e-mail to a bank customer that may look like a totally legitimate request from the bank to verify the user’s credentials (for example, user ID and password) or worse, to verify the individual’s social security number. Phishers use frequent mass mailings in the hope that even a small percentage of respondents will financially justify the effort.

Useful information about phishing can be found on the Anti-Phishing Working Group (APWG) website.14 The APWG is the global pan-industrial and law enforcement association focused on eliminating the fraud and identity theft that result from phishing, pharming, and e-mail spoofing of all types. APWG 2009 report shows that:

• The number of unique phishing websites detected in June 2009 rose to 49,084—the highest since April 2007’s record of 55,643 and the second-highest recorded since APWG began reporting this measurement.

• The number of hijacked brands ascended to an all-time high of 310 in March 2009 and remained at an elevated level.

• The total number of infected computers rose more than 66 percent to 11,937,944—now more than 54 percent of the total sample of scanned computers.

Payment services became phishing’s most targeted sector, displacing general financial services, and institutional customers still are a primary target of electronic criminals, with the majority of electronic record breaches linked to organized crime. A variant of phishing known as spear-phishing targets a phishing attack against a selected individual. The phishing text contains correct factual elements (personal identifiers) that correspond to the target/reader. Such targeted phishing messages are quite effective in convincing their intended victims of the presumed authenticity of the message.

Pharmers, on the other hand, try to increase the success ratio of stealing other people’s identification information by redirecting as many users as possible from legitimate commercial websites to malicious sites. The users get redirected to the false websites without their knowledge or consent, and these pharming sites usually look exactly the same as the legitimate site. But when users log in to the sites they think are genuine by entering their login name and password, the information is captured by criminals.

Of course, there are many other types of scams that are designed to steal people’s identities. These criminal actions have reached almost epidemic proportions and have become subject to numerous laws and government regulations. The variety of scams is so large that a number of advisory websites publish new scam warnings on a regular basis. Examples of these watchdog sites include www.LifeLock.com, the Identity Theft Resource Center (www.idtheftcenter.org), and Anti-Phishing Working Group (www.antiphishing.org).

GLBA, FCRA, Privacy, and Opt-Out

Other relevant regulations include National Do Not Call lists and the ability of customers to declare their privacy preferences as well as to opt-out from sharing their personal information with other companies or nonaffiliated third parties. The ability to opt-out is a provision of legislations such as the Gramm-Leach-Bliley Financial Modernization Act (GLBA) and the Fair Credit Reporting Act (FCRA).

The term opt-out means that, unless and until the customers inform their financial institution that the customer does not want them to share or sell customer data to other companies, the company is free to do so. The implication of this law is that the initial burden of privacy protection is on the customer, not on the company.

Contrast this with a stronger version of expressing the same choices—opt-in. This option prohibits the sharing or sale of customer data unless the customer explicitly agreed to allow such actions.

In addition to the opt-out option, additional privacy protection regulations are enabled by the National Do Not Call (DNC) Registry. The National Do Not Call Registry (www.DoNotCall.org) is a government organization that maintains a protected registry of individual phone numbers that their owners have opted to make unavailable for most telemarketing activities.

Recognizing customer privacy preferences such as opt-ins, opt-outs, and DNC allows companies to enhance the customer’s perception of being treated with respect and thus improves customers’ experience and strengthens their relationships with the organization. The ability to capture and enforce customer privacy preferences including opt-in/out choices is one of the design requirements for data integration solutions in the form of customer information files, enterprise data warehouses, CRM systems, and MDM Data Hubs.

Key Technical Implications of Data Security and Privacy Regulations on MDM Architecture

As you can see from the foregoing discussion, regulations such as the Sarbanes-Oxley Act, the Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act, and many others, have profound implications for the technical architecture and infrastructure of any data management solution. Of course, Master Data Management is becoming a focal point where these implications are clearly visible and have a significant impact. If we focus on the issues related to the protection of and controlling access to the information managed by a Master Data Management solution, we can summarize the technical implications of key regulations into a concise set of requirements that should include the following:

• Support for a layered information security framework.

• Support for flexible multifactor authentication with the level of authentication strength aligned to the risk profile.

• Support for policy-based, roles-based, and entitlements-based authorization.

• The ability to protect data managed by an MDM platform whether data is in transit (on the network) or at rest (on a storage device or in memory).

• Support for data integrity and confidentiality.

• Business-driven data availability.

• The ability to aggregate personal profile and financial reporting data only to an authorized individual.

• Auditability of the transactions and all data access and manipulation activities.

• Support for intrusion detection, prevention, and monitoring systems.

• Support for an inventory list of each third-party vendor relationship and its purpose.

• Support for event and workflow management.

• Support for real-time analytics and reporting.

• The ability to recognize and categorize all data that needs to be protected, including customer records, financial data, product and business plans, and similar information that can impact the market position of the organization.

• Support for a structured process that can keep track of all input and output data to mitigate business risk associated with disclosing private, confidential information about the company and its customers. This includes not only the authoritative data source but also all copies of this data. Indeed, unlike other auditable assets, a copy of data has the same intrinsic value as the original. Therefore, the tracking process should include an active data repository that maintains a current, up-to-date inventory of all data under management that needs to be protected and accounted for.

To sum up, the regulatory landscape that defines the “rules of engagement” related to the protection of information assets and identities of customers and parties has some profound implications for any IT infrastructure. By their very nature, Master Data Management solutions are targets of the majority of the regulations mentioned in this chapter. Thus, an MDM solution that is designed to integrate private confidential or financial data has to be architected and implemented to achieve a verifiable compliance state that supports PII and MNPI requirements. The remaining chapters of this part of the book describe design approaches that mitigate various information security risks while addressing the multitude of regulatory and compliance requirements.

References

1. http://www.businessdictionary.com/definition/risk-management.html.

2. http://security.practitioner.com/introduction/infosec_5_3_7.htm.

3. http://www.sec.gov/about/laws/soa2002.pdf.

4. http://banking.senate.gov/conf/.

5. http://www.ftc.gov/privacy/glbact/glbsub1.htm.

6. http://www.fdic.gov/news/news/financial/2001/fil0168.html.

7. http://www.fdic.gov/regulations/examinations/bsa/bsa_3.html.

8. http://www.basel-ii-risk.com/Basel-II/Basel-Three-Pillars/index.htm.

9. http://info.sen.ca.gov/pub/01-02/bill/sen/sb_1351-1400/sb_1386_bill_20020926_ chaptered.html.

10. http://www.coso.org/Publications/ERM/COSO_ERM_ExecutiveSummary.pdf.

11. Anti-Phishing Working Group, March 2009.

12. Gartner, Inc. February 2009, ID: 165825, “Data breach and financial crimes scare consumers away.”

13. http://www.spendonlife.com/guide/identity-theft-statistics.

14. http://www.antiphishing.org/.