CHAPTER

2

Why we customize the Web

Lydia B. Chilton, Robert C. Miller, Greg Little, Chen-Hsiang Yu

MIT CSAIL

ABSTRACT

The Web is increasingly an application platform comparable to the desktop, but its openness enables more customizations than were possible on the desktop. This chapter examines the kinds of customization seen on the Web, focusing on the highly extensible Mozilla Firefox Web browser, and compares and contrasts the motivations for Web customization with desktop customization.

INTRODUCTION

The modern Web has grown into a platform to rival the desktop, offering not only a wealth of information and media, but also applications. The combination of private data, public data, and desktop-quality applications has created a powerful computing environment. As people use the Web to shop, plan events, consume media, manage their personal information, and much more, they also want to customize the sites they use to shape them around their preferred workflow.

Fortunately, the openness, flexibility, and common standards of the Web platform enable customizations that would not have been possible on the desktop. Web pages primarily use HTML markup to display their user interfaces, and the Document Object Model (DOM) representation for HTML inside a Web browser makes it possible to inspect and modify the page. Similarly, many Web applications are divided into individual pages with unique identifiers (URLs). State changes in the user interface are triggered by clicking hyperlinks or submitting forms, so customizations can observe state changes and cause them automatically, even without the application’s help. On the desktop, by contrast, customizations must be explicitly supported by the application developer, by providing a programming interface or customization interface. The openness of the Web platform has been a fertile ground for third-party customization systems, many of which are described in this book.

This chapter looks at the landscape of Web customization, particularly for the Mozilla Firefox Web browser. We use the term customization in a broad sense to refer to any modification to a Web site by an end user or third party (not the original Web developer). In this chapter, however, we focus on customizations hosted by the Web browser. Customizations of this sort may automate interaction with the site – clicking links, filling in forms, and extracting data automatically. They may change the site’s appearance by adding, removing, or rearranging page components. Or they may combine a site with other Web sites, commonly called a mashup.

Our focus on browser-hosted customizations glosses over customization features provided by Web sites themselves, such as customizable portals like iGoogle and My Yahoo. Also outside the scope of this chapter is the rich world of mashups hosted by third-party Web sites, such as the classic HousingMaps mashup of craigslist and Google Maps (http://www.housingmaps.com), as well as Web-hosted programming systems like Yahoo Pipes (http://www.pipes.yahoo.com).

One reason we focus on browser-hosted customizations is that many of the systems described in this book fall into this category. Another reason is that the Web browser is the component of the Web platform that is closest to the user and most under the user’s control, as opposed to Web sites, which might be controlled by corporate entities or be more subject to legal or intellectual property restrictions. As a result, browser-hosted customizations may be the best reflection of user preferences and needs, and the best expression of user freedom, so this is where we focus our attention.

We will show that users customize the Web for many of the same reasons users customize desktop applications: to better suit their needs by making tasks less repetitive or aspects of browsing less annoying. On the Web, some of these problems arise because tasks span multiple sites, and others because Web sites may be underdeveloped and have usability problems or missing functionality. A final reason to customize the Web, not previously seen on the desktop, is to “bend the rules,” circumventing legal restrictions or the intentions of the site.

The rest of this chapter is organized as follows. We start by looking back at previous research, particularly about customization on the desktop, which uncovered motivations and practices that continue to be true on the Web. We then survey some examples of customizations for Firefox, drawing from public repositories of Firefox extensions, Greasemonkey, Chickenfoot, and CoScripter scripts. We follow with a discussion of motivations for customization revealed by these examples, some of them unique to the Web platform.

CUSTOMIZATION ON THE DESKTOP

Early research on customization was exclusively on desktop customization. In many ways, Web customization achieves the same basic goal as traditional customization: making the interface match the user’s needs. Yet the Web’s unique platform and culture bring about several differences from traditional customization. Some of the barriers to desktop customization aren’t as prevalent on the Web; the types of changes that users make on the Web are different, and customization on the Web is driven by a wider set of motivations.

In a study of the WordPerfect word processor for Windows, Page et al. describe five types of customization found on the desktop (Page, Johnsgard, & Albert, 1996). Most common was (1) setting general preferences; followed by (2) using or writing macros to enhance functionality of the application; (3) granting easier access to functionality, typically by customizing the toolbar with a shortcut; (4) “changing which interface tools were displayed,” for example, showing or hiding the Ruler Bar; and (5) changing the visual appearance of the application. These categories are certainly relevant to Web customization, particularly enhancing functionality and granting easier assess to existing functionality.

Wendy Mackay studied a community of customization around a shared software environment, MIT’s Project Athena, and identified four classes of reasons why users customized (Mackay, 1991). The top technological reason cited was that “something broke,” so that the customization was actually a patch. The top personal reasons cited were first that the user noticed they were doing something repetitively, and second that something was “getting annoying.” All of these reasons can be found in Web customization as well.

In the same study, Mackay describes barriers to customization reported by users. The most reported barrier overall was lack of time, but the chief technical reasons were that it was simply too difficult and that the application programming interfaces (APIs) were poor. End user programming systems for the Web have tried to ease the technical burden. Additionally, customizable Web sites all use the same technology, and have the same structure – the Document Object Model of HTML, modifiable with JavaScript – which reduces the need to rely on APIs.

In a study of users sharing customizations stored in text files (Mackay, 1990), Mackay highlights how important it is that authors of customizations share their work with nonprogrammers who want customizations but don’t know how to write them. The same culture of sharing is just as important and widely prevalent on the Web. Mackay describes a group of “translators” who introduce the nonprogrammers to existing customizations. The Web has its own channels for distributing customizations that rely not just on repositories of customizations (like blogs and wikis) but also on personal interactions (email, forums, comments, and so on).

Mackay recommends that users “want to customize patterns of behavior rather than lists of features.” Desktop applications today still concentrate on customizing lists of features, such as the commands available on a toolbar. End-user programming on the Web, however, leans heavily toward what Mackay recommends – adding new features, combining features in new ways, and streamlining the process of completing tasks, as is seen in the examples later in this chapter.

The classic end user programming system Buttons (MacLean et al., 1990) is a customization tool built around macros that can be recorded and replayed by pressing a single button. MacLean et al. point out that there is a “gentle slope” of customizability where technical inclination governs ability and willingness to customize. Web customization exhibits a similar slope. At the very basic level, users have to know about and trust browser extensions in order to even run browser-hosted customizations. To start writing customizations, a user must become familiar with an end user programming tool. At the programming level, it may be necessary for customizers to know about the HTML DOM, JavaScript, and browser APIs, such as Firefox’s XPCOM components.

CUSTOMIZATION ON THE WEB

More recently, researchers have studied practices of customization on the Web, particularly mashup creation and scripting. The authors of Chapter 20 found through surveys of mashup developers that mapping sites (specifically Google Maps and Yahoo Maps) were among the most popular to mash up with other sites, and that many programming obstacles to mashup creation still exist. Wong and Hong surveyed mashup artifacts rather than the people who created them, examining two public directories of Web-hosted mashups (ProgrammableWeb and Mashup Awards) in order to discover interesting characteristics and dimensions for classifying existing mashups (Wong & Hong, 2000). Although aggregation of data from multiple sites was a very common feature, Wong and Hong also found mashups designed to personalize a site, filter its contents, or present its data using an alternative interface. This chapter takes a similar approach to Wong and Hong, surveying customizations in four public repositories, but focusing on browser-hosted customizations.

The CoScripter system in particular has been the subject of two studies of Web customization practice. Leshed et al. (2008) studied how CoScripter was used by internal IBM users, whereas Bogart et al. (2008) looked at much wider use on the Web after CoScripter was released to the public. Some of the findings from these two studies are cited in the next section.

EXAMPLES OF WEB CUSTOMIZATION

We now turn to a brief informal survey of examples of Web customization found on today’s Web. These examples are mostly drawn from the public repositories of four customization systems, all designed for the Mozilla Firefox Web browser:

• Firefox extensions (https://developer.mozilla.org/en/Extensions) add new user interface elements and functionality to the browser, generally using JavaScript and HTML or XUL (Fire-fox’s user interface language).

• Greasemonkey (http://www.greasespot.net) allows user-provided JavaScript code to be injected into a Web page and customizes the way it looks or acts.

• Chickenfoot (see Chapter 3) is a JavaScript programming environment embedded as a sidebar in the browser, with a command library that makes it easier to customize and automate a Web page without understanding the internal structure of the Web page.

• CoScripter (see Chapter 5) allows an end user to record a browsing script (a sequence of button or link clicks and form fill-in actions) and replay it to automate interaction with the browser, using a natural language-like representation for the recorded script so that knowledge of a programming language like JavaScript is not required.

Each of these systems has a public repository of examples, mostly written by users, not the system’s developers. Firefox extensions are hosted by a Mozilla Web site (https://addons.mozilla.org/en-US/firefox/), whereas Greasemonkey has a public scripts wiki (http://userscripts.org), as do Chickenfoot (http://groups.csail.mit.edu/uid/chickenfoot/scripts/index.php/Main_Page) and CoScripter (http://coscripter.researchlabs.ibm.com). CoScripter is worth special mention here, because all CoScripter scripts are stored on the wiki automatically. The user can choose to make a script public or private, but no special effort is required to publish a script to the site, and the developers of CoScripter have been able to study both public and private scripts.

Other browser-hosted customization techniques exist. Bookmarklets are small chunks of JavaScript encoded into a JavaScript URL, which can be invoked when a Web page is visible, to change how that page looks and acts. Bookmarklets have the advantage of being supported by all major browsers (assuming the JavaScript code in the bookmarklet is written portably). Other browser-specific systems include User JavaScript for the Opera browser (http://www.opera.com/browser/tutorials/userjs), which is similar to Greasemonkey, and Browser Helper Objects for Internet Explorer (http://msdn.microsoft.com/en-us/library/bb250436.aspx), which are similar to Firefox extensions.

Since this survey focuses mainly on customizations for Firefox that users have chosen to publish in a common repository, it may not reflect all the ways that Web customization is being used in the wild, but these examples show at least some of the variety, breadth, and, in particular, varying motivations that drive users to customize the Web.

The rest of this section describes the following six interesting dimensions of Web customizations:

• The kind of site customized

• The nature of the customization (shortcut, simplification, mashup, etc.)

• Generic customizations (for any Web site) vs. site-specific ones

• Customizations for one-shot tasks vs. repeated use

• The creator of the customization, who is not always an end user of the site

• The relationship between the customization and the targeted site – sometimes collaborative, sometimes breaking the rules

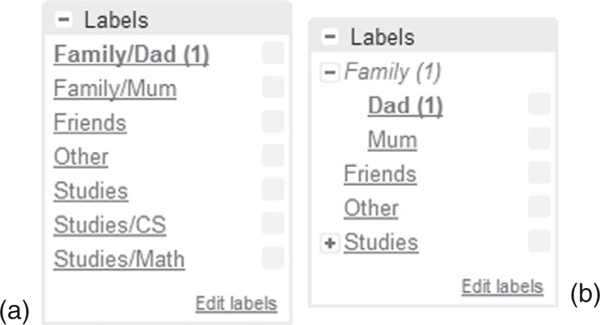

Kind of Web site. Many scripts target Web sites for personal information management (PIM), such as email, calendars, and to-do lists, probably because users of these sites spend much time using them. Gmail alone has spawned a rich community of customizers. One popular Firefox extension, Better Gmail, bundles up several Greasemonkey scripts that change how Gmail works, among them keyboard macros, saved searches, and forced use of a secure connection. Folders4Gmail (Figure 2.1) is a Greasemonkey script that allows Gmail’s flat labels to be organized into a hierarchy of folders. Google Account Multi-Login speeds up switching between different Gmail accounts with different usernames and passwords.

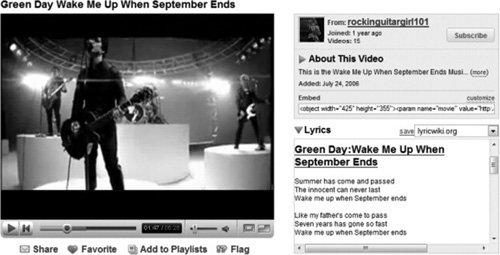

Other customizations target media sites, particularly for video and photo sharing. Since YouTube is widely used for posting and watching music videos, YouTube Lyrics (Figure 2.2) adds a box to video pages that searches for and displays the lyrics to the song. Other scripts and extensions support downloading videos from YouTube, and combining The Internet Movie Database (IMDb) with Bit-Torrent (a popular technology for downloading movies online). Better Flickr bundles up several scripts that enhance the usability of the Flickr photo-sharing site, including a photo magnifier, shortcuts for replying to other users’ comments, and a rich text editor for comments. GMiF embeds a Google Map in a Flickr photo page to display the location of a geotagged photo.

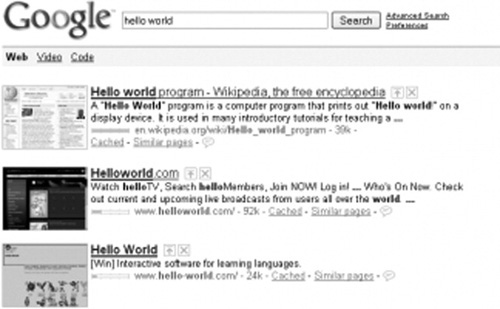

A third major category of customized sites are search engines. The GooglePreview extension (Figure 2.3) inserts Web page thumbnails into Google and Yahoo search results, and SurfCanyon reranks search results (Google, Yahoo, craigslist, LexisNexis) and filters out undesirable sites.

PIM, media, and search may be important areas of customization for two reasons: first, because users’ interaction with these sites may be highly idiosyncratic and personalized; and second, because the developers of these sites sometimes have their hands tied for legal or practical reasons, preventing them from implementing features that end users may demand. Customization is thus forced to pick up the slack.

A fourth kind of site commonly customized is online games. Travian Beyond is a Greasemonkey script for the Travian Web-based multiplayer game, which adds shortcuts and provides more sensible defaults to improve the usability of the game’s original interface. Scripts for other gaming sites are more interested in bending (or breaking) the rules of the game – automatically farming gold, for example, or disabling ads to make the free version of a game feel more like playing the premium version.

FIGURE 2.1

Folders4Gmail converts Gmail’s flat list of labels (a) into a tree (b).

FIGURE 2.2

YouTube Lyrics adds a lyrics box to YouTube music videos.

FIGURE 2.3

GooglePreview shows Web page thumbnails in search result listings.

Customization is certainly not limited to Web sites in the four areas mentioned, however, and it seems likely that the tail of the distribution is long.

Kind of customization. Many scripts are shortcuts, making a frequent or repeated task in the site more efficient. A classic example of a shortcut is Gmail Delete Button, a Greasemonkey script that added a delete button to Gmail’s interface. When this script was created, deleting a message was possible but inconvenient. The Greasemonkey script simply makes the function accessible with one click. Another shortcut is a script that changes links to Gmail and Google Calendar so that they simply switch to an existing Gmail or Google Calendar tab rather than opening a new one (initially prototyped in Chickenfoot, and subsequently a popular Firefox extension). Other notable Chickenfoot examples include a script that adds a recently-viewed-pages box to MediaWiki, and one that forces all YouTube videos viewed into high-quality mode whenever available. Many CoScripter scripts surveyed by their developers also fall into this category. Because CoScripter was widely deployed and used within IBM before being made public, Bogart et al. found that many popular shortcuts automate internal IBM systems, such as voicemail, telephony, and business processes (Bogart et al., 2008).

A particular kind of shortcut is automatic form fill-in, which fills in a form with defaults. Major Web browsers, including Firefox, already provide this ability for login forms, but generally don’t have good support for users who must manage multiple accounts per site. The Google Account Multi-Login mentioned previously is one script for this problem. Another is a Chickenfoot script for the Mailman mailing list system, which automatically selects the right password to use for administering a mailing list. For general form fill-in, several Firefox extensions exist, the most widely installed probably being Google Toolbar. Many CoScripter and Chickenfoot scripts also do form fill-in for specific sites and purposes, under more control by the user than a generic extension.

Simplification customizations reduce clutter and distraction, or eliminate unnecessary features. One Chickenfoot script simplifies iGoogle (Google’s home page portal) by removing the logo and search box, which otherwise occupy half the screen. Another script used by one of the authors on Gmail hides the fact that there are unread messages in the Drafts folder (turning off the boldface and removing the unread message count). For general Web browsing, two very popular Firefox extensions are Adblock Plus and Flashblock, which remove advertisements and Flash objects from Web pages.

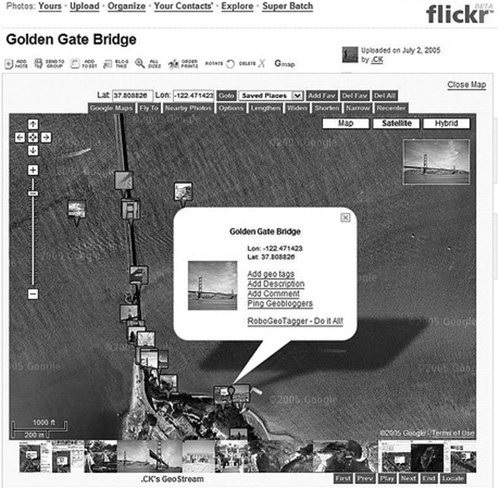

Finally, mashups combine two or more Web sites or services. The YouTube Lyrics script mentioned previously is a mashup between YouTube and a number of lyrics search engines. The GMiF extension (Figure 2.4) embeds a Google Map into a Flickr page to show where the photo was taken (assuming geographical metadata is found in the photo). The Delegate to Remember The Milk extension allows a Gmail message to be forwarded to the Remember The Milk to-do list site with a single click. Chickenfoot mashups include a script that posts the currently viewed item on Amazon to a Gnolia wishlist and a price comparison script for the online used textbook exchange, MIT412 (http://mit412.com), and Barnes & Noble. Finally, Chickenwire, a Chickenfoot-based mashup created by two of the authors, supports connecting YouTube and Wikipedia, so that Wikipedia pages about songs or movies can be linked to YouTube music videos or movie clips.

FIGURE 2.4

GMiF mashes up Flickr with Google Maps.

Generic vs. site-specific customization. The examples so far have targeted specific Web sites, such as Gmail, YouTube, Flickr, and Wikipedia, or specific Web interfaces, such as MediaWiki and Mailman. But other customizations are designed to change the overall experience of browsing the Web. Generic simplifiers like Adblock Plus, and generic form fill-in tools like Google Toolbar, certainly fall into this category. A generic shortcut is the Interclue extension, which pops up a preview of a hyperlink’s destination when the mouse hovers over the link.

FIGURE 2.5

Vocabulary word highlighting using a Chickenfoot script.

Other generic scripts focus on reading on the Web. A vocabulary-builder script for Chickenfoot (Figure 2.5) highlights words from a vocabulary list wherever they happen to be found in Web pages, and pops up definitions on mouseover, so that students can learn words in context. The LookItUp Greasemonkey script can pop up the dictionary definition of any selected word. For foreign languages, the Globefish extension helps a reader by translating selected text, and helps a writer with idioms and awkward phrasing by measuring the popularity of a phrase with Web searches. Finally, the Froggy extension developed by one of the authors reduces distraction and splits paragraphs into sentences, to help nonnative English readers increase comprehension of the text.

Other scripts help with text entry. The Virtual Keyboard Interface Greasemonkey script displays an onscreen keyboard under a textbox, for entering special characters, avoiding keyloggers, and accessibility. Chickenfoot scripts allow any textbox to be resized and add commands for joining paragraphs (removing hard line breaks) and for splitting them (inserting hard line breaks).

Another common generic script concatenates a series of Web pages, such as a multipage article or a list of search results, using a table of contents or Next link to discover the subsequent pages. An early Chickenfoot example did this, as do the Greasemonkey scripts GoogleAutoPager and AutoPagerize.

Because generic customizations essentially add functionality to the overall browser experience, they raise questions about whether the browser itself should evolve to include these features, and if not, why not. Similar questions arise about site-specific customizations; why doesn’t the site itself implement these features, particularly when a customization has proved popular? Sometimes the site eventually does, but sometimes it can’t, for legal or practical reasons.

One-shot vs. repeated use. Most of these examples have been designed for repeated use over time by the same user, and have little value if used only once. Another kind of script is intended for a one-shot task that may never be needed by the user again. One-shot scripts generally use automation or scraping to do a large task. These scripts are worth creating when the size of the task is large enough that the effort put into writing the script pays off in reduced manual effort (Potter, 1993).

An example of a one-shot task is a Chickenfoot script that clears the bounce flag on all subscribers to a Mailman mailing list. Mailman’s interface makes this task tedious to do manually, first because subscribers are divided up into pages by initial letter (A, B, C, …), forcing the user to visit 26 or more pages for a large mailing list; and second, because each bounce flag is a checkbox next to the subscriber’s email address, with no command for selecting or deselecting all checkboxes at once. The Chickenfoot script automates stepping through the pages, clearing all the checkboxes.

Other examples of one-shot automation include clean-up tasks for a wiki, transferring course grades from a college information system to a grad school application, scraping school tuition data into a spreadsheet, and calculating scores for a school contest. These examples are Chickenfoot scripts written by one or more of the authors. One-shot automation is hard to find in public repositories, since it rarely seems worth publishing. Also, the programming system used must have a low threshold to make it practical to create the one-shot script in the first place. One-shot Firefox extensions seem highly unlikely, because building a Firefox extension is a serious investment. Chickenfoot and CoScripter are easier to use for that purpose.

Creator of the customization. Most customizations are created by users of the Web sites they target, albeit those with more programming skills than the average user. But the customizer is not always an end user. For example, several popular Firefox extensions have been published by Web sites themselves, including Google Toolbar, Yahoo Toolbar, eBay Sidebar, and Remember The Milk for Gmail. These extensions may not strictly fit the definition of customization we use in this chapter, since they are provided by the original Web developer rather than a third party. They extend the Web site deeper into the browser, to run code with stronger permissions and more functionality (e.g., storing data locally or mashing up data with other sites), or to provide a more persistent, browser-level interface that follows the user around while they browse elsewhere on the Web.

Another situation arises when the customizer is not just an end user but also the owner of the site. Open source systems like Mailman and MediaWiki may be locally installed in an organization, and the source code for the system may be technically available to be changed, and yet Web customization may still be a more viable route. The authors have written many Chickenfoot scripts for systems that their organization owns and controls, including the Mailman bounce-flag script, a script for MediaWiki editing that provides a save-and-continue-editing command, and several scripts for the Flyspray bug database that provide simplification and shortcuts (see the section, “Making a bug tracker more dynamic,” in Chapter 3). Many CoScripter scripts created for internal IBM use may also fall in this category, because IBM owns and controls many of the systems that IBM’s own employees find it necessary to customize.

Finally, the customizer may be neither an end user nor a developer, but a researcher exploring new ideas in Web user interfaces. The four customization systems surveyed here have proven to be fertile ground for research prototypes, many of which are described in this book. Firefox extensions created for research purposes include Web summaries (Chapter 12), Transcendence (Bigham et al., 2008), and Intel MashMaker (Chapter 9). IE Browser Helper Objects were used by Creo (Chapter 4). Notable research uses of Greasemonkey include Accessmonkey (Bigham & Ladner, 2007), PrintMonkey (Baldwin, Rowson, & Coady, 2008), SparTag.us (Hong et al., 2008), Kalpana (Ankolekar & Vrandecic, 2008), and table browsing for small screens (Tajima & Ohnishi, 2008). In our own group, Chickenfoot has been used in Kangaroo (see the section, “Adding faces to Webmail,” in Chapter 3), Smart Bookmarks (Hupp & Miller, 2007), and Inky (see Chapter 15). CoScripter has contributed to Highlight (Chapter 6) and Vegemite (Lin et al., 2009).

Is it an arms race? A final consideration is the relationship between the customization and the targeted Web site. Some customizations bend the rules of a site. In a survey of public CoScripter scripts, Bogart et al. (2008) found that 18% of scripts sampled were designed to circumvent an assumption made by the site that a human user was clicking on a button or hyperlink. One example is Automated Click for Charity, a script that visits charity Web sites and clicks on links to trigger donations without viewing the ads that pay for those donations. Other examples include ballot stuffing for online polls and automatic players for online lotteries or multiplayer games.

Many Web sites have Terms of Service agreements for their users, and these agreements may forbid certain kinds of automation. Sites may defend against customizations by technical means (such as CAPTCHA tests that distinguish humans from scripts) or legal means. One case concerned a Firefox extension that injects a button into Amazon music and video pages, linking to downloadable content on the illicit file-sharing site The Pirate Bay. The site hosting the extension was reportedly taken down by a cease and desist order from Amazon (Kravets, 2008).

Conversely, sites can welcome and support customizations. Gmail is noteworthy in this regard, providing the Gmail API for Greasemonkey to make Greasemonkey scripts easier to write and more robust to future changes.

Sites can also pay attention to what customizers are saying with their customizations, and respond with improvements. Gmail is notable here too. The Gmail Delete Button mentioned as our first example has become obsolete, because Gmail now includes a delete button.

WHY WE CUSTOMIZE

The basic reason users make customizations is that users want applications that were written for “just anybody” to be optimized for their work habits and preferences. On the Web, this means that users want (1) individual sites to have the features they need, (2) sites to be able to work together for certain tasks, and (3) improvements to Web browsing in general, that is, customizations that affect all sites that they visit. In addition, many Web sites are less developed than most desktop software. Some sites get launched before they are fully functional, and some sites don’t get regularly updated and have interfaces that could be improved from the user standpoint.

From surveying existing Web customizations, we can say that some of the prevalent reasons Mackay found for users making desktop software customizations in her 1991 paper are still true on the Web today.

Mackay identified one of the top reasons to customize being that the user became aware of doing something repetitive. Many customizations on the Web have been written to eliminate redundant actions. For users who are constantly clicking away ads, there are ad blocking customizations. For users who spend time looking up uncommon words, there are customizations that add definitions for certain words in a tool tip. For users who commonly search for icons, a customization adds a single button to Google that searches for small (icon-sized) images. For users who repetitively look at the large product images while shopping online, there are customizations to load all the full-size images automatically.

Additionally, Mackay reported that feeling annoyed was a reason for customization. The Web has seen customizations to work around the annoyance of not being able to bookmark pages such as airline fare results. There are customizations to reduce the saliency of ads on a page to make reading the content less annoying. For users who find it annoying that Ctrl-S doesn’t “save and continue” in MediaWiki edit pages, there is a customization to bind the shortcut to that action on all MediaWiki edit pages.

Many repetitive tasks span multiple pages: shopping comparisons, looking up words in an online dictionary, and looking up airfares, for example. Web customizations can navigate through a sequence of pages or mash up multiple Web sites, whereas it is uncommon for desktop customizations to use more than one application. GooglePreview inserts Web page thumbnails in Google and Yahoo search results.

Some of the customizations we have seen are changes to individual sites that fix usability problems that the sites could fix eventually. Users who make these changes don’t want to wait; they want to stay ahead of the curve. This includes simple changes like moving the login interface to the top of the page where it is more useful, and adding a delete button to Gmail, which is a change Gmail eventually made.

One way in which Web customization is unique is that for some sites, customization is the only way to get certain features, because the site will never provide them. Legal restrictions prevent some sites from adding features, and some commercial sites have an disincentive to provide certain features. Bogart et al. refer to customizations that circumvent the intentions of a site as “changing the rules” (Bogart et al., 2008). Because legal restrictions prevent Wikipedia from hosting copyrighted content, one customization keeps its own list of links to YouTube videos relevant to each Wikipedia page and includes those videos every time the user visits a Wikipedia page. YouTube doesn’t allow users to download its video content largely for legal reasons, but there are several customizations that make it trivial to download the videos as they stream. There are also customizations to recommend torrent sites for particular movies on IMDb. Among the CoScripter customizations designed to change the rules, the most devious may be a script to automate voting on a poll whose winner receives money. Other changing-the-rules customizations include injecting one shopping site with price comparisons to other sites, and scrubbing ads out of applications such as Gmail or sponsored search results in search engines.

In summary, users customize the Web for some of the same reasons users usually customize: to better suit their needs by making tasks less repetitive or aspects of browsing less annoying. On the Web, some of these problems arise because tasks span multiple sites, and some of them arise because Web sites can be underdeveloped and have usability problems or missing functionality. Lastly, an important reason to customize the Web is to “bend the rules,” circumventing legal restrictions or the intentions of the site.

SUMMARY AND FUTURE DIRECTIONS

This chapter has shown a variety of motivations for customization in the Web browser. Customizations were fundamentally enabled by both the inherent openness of Web technology and the particular decision by Mozilla developers to make Firefox highly extensible. The threshold of customization was lowered still further by Greasemonkey, Chickenfoot, and CoScripter, all of which were built on top of Firefox’s extension mechanism.

Although one can expect the world of Web customization to continue to grow in size and richness, challenges remain. One continuing problem is robustness. Web sites change over time, in appearance and organization and internal structure. Customizations that target a changing Web site will decay unless maintained and updated. If the Web site commits to supporting customizations, as Gmail does through its Greasemonkey API, then this problem can be mitigated, but it seems unlikely that more than a tiny fraction of Web sites will ever do this. Customization systems that target the rendered user interface of the site (as Chickenfoot and CoScripter do) may prove more robust to change than those that operate on internal HTML/JavaScript interfaces (like Greasemonkey), but this remains to be proven.

Another perennial challenge comes from programming platforms that run inside the browser but do not provide the same degree of reflection and modification as HTML and JavaScript. Java applets are probably the oldest example, but Adobe Flash/Flex and Microsoft Silverlight are becoming widely used as well. Currently these platforms are used more for embedding components (like video players or ads) in a mostly HTML site, rather than implementing the entire site, but as the trend toward richer interactive experience continues, site developers may find the new platforms very enticing. A site whose entire functionality is provided by Flash or Silverlight can’t be customized using the systems described in this chapter. New approaches may be required, lest we slip back toward the closed and less customizable world of the desktop.

We have focused on browser-hosted customizations in this chapter, but a serious limitation of this approach is that the user’s customizations don’t easily move with them as they use different browsers on different computers. CoScripter has an advantage here, because it stores all scripts on a wiki so that any Firefox browser with CoScripter installed can access them. Mozilla Weave (https://mozillalabs.com/weave/) is an effort to solve this problem in general, by synchronizing Firefox extensions and other preferences across multiple installations of the browser.

Finally, although we made a distinction in this chapter between “desktop” and “Web,” in fact the Web platform we considered might better be called the “Web desktop” – the Web as seen by a conventional Web browser like Mozilla Firefox running on a conventional desktop or laptop computer with a big screen, keyboard, and pointing device. The future of the Web platform is much more diverse. Web browsers will turn up in a variety of different devices and contexts, including cell phones, netbooks, TV set-top boxes, home media servers, and wall displays. Mobile Web customization is already an active area of research, as demonstrated by Creo (Chapter 2) and Highlight (Chapter 6), but much work remains to be done to give users the power to customize the Web of the future.