8. Employee Benefit Accounting

Aims and objectives of this chapter

• Review specific accounting issues related to health and welfare employee benefit programs

• Discuss the standards framework for the accounting and reporting of employee benefit programs

• Establish the difference between defined contribution and defined benefit programs within a health and welfare employee benefit structure

• Discuss the relevant points of FASB 965 – Employee Benefits

• Discuss the concept of claims incurred but not reported

• Review the reporting requirements for postretirement health plans

• Discuss the concept of self-funding of health and welfare plans

• Explain self-funding within the ERISA structure

• Review reporting standards for health and welfare plans under IFRS – IAS 19 standards

• Explain the financial reporting requirements for employee benefit plans, focusing on health and welfare plans

Employee benefit programs are a crucial element of the total compensation system for any organization. Normally, the employee benefit element of the total compensation structure makes up about a third of the average total compensation. Within the employee benefit structure, the healthcare benefit element is experiencing ever-increasing cost inflation. Because of healthcare costs, the total benefit component can create significant cost exposure for most organizations. This makes the review and comprehensive analysis of employee benefits very important. The next three chapters cover the employee benefit component of the total compensation system.

We now turn our attention to the accounting and finance issues related to employee benefit programs as a whole.

Before 1980, U.S. Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP) had not issued any guidelines for the accounting treatment of employee benefit plans. So before 1980, in actual practice the principles used for the accounting of employee benefits was widely divergent. In March 1980, the Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) issued the Statement of Financial Accounting Standards (SFAS) No. 35, Accounting and Reporting by Defined Benefit Plans. Because these standards addressed only defined-benefit plans, the American Institute of Certified Public Accountants (AICPA) issued guidelines for the accounting of defined-contribution and health and welfare plans. The guidance was incorporated in AICPA’s Audit and Accounting Guide: Audits of Employee Benefit Plans. The Audit and Accounting guide document was issued in 1983. Since then, the guidance has been updated quite a few times. In August 1992, FASB issued its Statement of Financial Standards No. 110, Reporting by Defined Benefit Pension Plans of Investment Contracts, which extended the fair value accounting to certain insurance contracts.

Specialized accounting and reporting guidance for employee benefit plans is now included in the FASB ASC 900s1 topics. FASB ASC 960 addresses defined benefit pension plan accounting and reporting, FASB ASC 962 addresses defined contribution pension plan accounting and reporting, and FASB ASC 965 addresses health and welfare benefit plan accounting and reporting.

1 Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) – Accounting Standard Codification (ASC).

Employee benefit programs can be generally classified into three categories:

• Risk benefits (covering medical, disability, and life insurance benefits)

• Time-away-from-work benefits

• Savings and retirement benefits (sometimes also called wealth-accumulation programs)

This chapter and Chapter 9, “Healthcare Benefits Cost Management,” discuss the accounting and finance implications of the first category of benefits. In this chapter, we focus on the accounting and financial reporting issues connected to health and welfare plans. Chapter 9 is devoted to the important issues of controlling and managing healthcare costs. Chapter 10, “The Accounting and Financing of Retirement Plans,” then discusses the third category of employee benefits: retirement benefits. Retirement benefits entail many accounting and finance implications (and so require a more comprehensive analysis).

The Standards Framework

Health and welfare program accounting in the United States is influenced by two significant guiding principles as codified in the U.S. GAAP (FASB) and the Employee Retirement Security Act (ERISA). Internationally, the guiding principle is the International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS). In the U.S. GAAP, the accounting for health and welfare plans is codified in FASB ASC regulation 965, and the IFRS standard is in IAS 19.

Guiding our discussions throughout this chapter are the rules, regulations, and principles for the accounting of health and welfare benefit plans both under the U.S. GAAP and the IFRS (that is, FAS 965 and IAS 19, respectively). We discuss relevant elements of the accounting requirements under both codes. If you want a detailed analysis and understanding of the codes, you can review the complete codes at the respective Web sites (www.fasb.org and www.ifrs.org).

Companies in the United States have been analyzing the differences between the IFRS and the U.S. GAAP in anticipation of the convergence of the standards. All parties are waiting to find out when a requirement will be imposed by rule-making bodies requiring U.S. companies to adopt IFRS standards. The Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) had stated that they would evaluate the feasibility of requiring IFRS conversion in 2011. The convergence time-line indicates that the earliest years the SEC would require U.S. IFRS conversion is 2014 to 2016.

Analyzing, interpreting, and understanding the FASB standards with respect to employee benefit accounting is a worthwhile exercise. However, we also need to do the same analysis with the IFRS standards in mind. This is needed because U.S. companies will face convergence in the near future. Looking at the accounting principles under both the standards will assist in the execution of the convergence effort if and when it is needed. Later in this chapter, we look at IFRS regulations as they pertain to health and welfare plans. The discussion that follows is based on a direct analysis, interpretation, and discussion of the standards.2

2 FASB 965 Plan Accounting–Health and Welfare Plans (based on an analysis of FASB 965).

Defined Contribution Versus Defined Benefit Plans

Defined contribution health and welfare plans differ from defined benefit health and welfare plans. A defined contribution health and welfare plan keeps a record of each individual plan participant’s account. Records are kept of each participant’s contribution and the employer’s contribution attributable to that employee.

A defined benefit health and welfare plan3 specifies a defined benefit, which may be a reimbursement to the covered plan participant or a direct payment to providers or third-party insurers for the cost of stipulated services on behalf of the participating employee. Defined benefit plans provide participants with a specifically determined benefit based on a formula provided in the plans, whereas defined contribution plans provide benefits based on amounts contributed to an employee’s individual account.

3 Hicks, S.W., “Accounting and Reporting by Health and Welfare Plans,” Journal of Accounting, Vol. 174, Issue 6, 1992.

Both the types adjust values based on the following:4

4 FASB – 965 – 325 – 05 – 2; www.fasb.org.

• Forfeitures

• Investment experience

• Administrative expenses

Each type of plan provides a benefit that has value. Therefore, the defined benefit health and welfare plan’s financial statements need to provide financial information that will aid in understanding and assessing the plan’s present and future ability to pay its benefit obligations when they become payable. To meet this objective, a plan’s financial statements should provide information about the plan assets and its benefit obligations, the results of transactions or events affecting the plan’s assets and liabilities, and any other pertinent information necessary for users to analyze the information provided.

The different types of defined benefit health and welfare plans (multiemployer and single employer) should separately report benefit obligations, including postretirement benefit obligations.

Section 965 Explained5

5 In this part of the chapter, we are interpreting, adapting, and explaining relevant code sections (stating the relevant section) of FASB 965, www.fasb.org.

Benefit Payments – 965-30-25-1: Health and welfare plans are able to process benefit payments directly, or the employer may retain a third-party administrator (TPA) through an administrative service arrangement (ASA). Benefits need to be paid by both fully and partially self-funded plans.

Premiums Due Under Insurance Arrangements – 965-30-25-3: Premiums due but not yet paid should be a part of the accounting of any obligation.

Postemployment Benefits – 965-30-25-3: Plans specially designed to provide postemployment benefits need to recognize a benefit obligation for current plan participants based on amounts that will be paid in future periods if certain conditions are met. The conditions are as follows:

• The participant’s right to receive the benefit needs to be based on services already provided.

• The participant has a vested benefit.

• There is a high probability of making the payment.

• The amount needs to be estimated in an accurate manner.

The exception to the rule is when all employees are provided the same benefits upon the occurrence of another specific event, such as medical benefits provided under a disability plan. In disability plans, medical benefits are paid regardless of the length of service. These disability plans usually do not have a vesting provision. Disability benefits need to be accrued from the start date of the disability (965-30-25-4).

Obligations for Premium Deficits – 965-30-25-5: In fully insured experience-rated plans, the experience ratings determined directly by insurance companies or estimates developed by those companies can result in deficits. Premium deficits need to be included in the total benefit obligation if both the following criteria are met:

• It is probable that the deficit will be applied against the amounts of future premiums or future experience rated refunds. The determination has to consider both of the following:

• To what extent the insurance contract requires payment of the deficits

• The plan’s desire to transfer coverage to another insurance company

• And the amount of the deficit can be estimated in a reasonable manner.

Recognition of Employer Contributions – 965-310-25-1: If there is formal commitment to make the employer contribution, there has to be documented evidence of the commitment. Documentary evidence can include the following:

• A resolution of a governing body signing off on this commitment.

• Evidence of a continuing pattern of making payments after the end of a plan year. This payment pattern needs to be made under a funding policy.

• Evidence of a deduction of a contribution taken for federal tax purposes. The deduction should be for periods ending on or before the financial statement date.

• Evidence of an accounting recognition of the contribution as a current expense payment liability. It is just not sufficient to show on the balance sheet that there is accrued liability. It is also insufficient evidence if the statement simply reflects that an accrued liability amount exceeds the plan’s assets available to meet the plan’s obligations.

Recognition of Premiums Paid to Insurance Companies – 965-310-25-2: This depends on whether a premium was paid to an insurance entity. It also depends on whether the premium payments were for the transfer of risk or merely a deposit. An analysis is required to determine the extent of the risk transfer to the insurance company. To mitigate the risk transfer, insurance companies might require a deposit be placed that can be applied toward possible future losses. The deposits need to be reported as plan assets until the amounts are used to pay premiums. Premium stabilization reserves that are maintained when premiums paid are in excess of claims and other charges paid should also be reported as assets of the plan until the reserves are used to pay premiums. If these reserves are forfeitable when the insurance contract is terminated, this possibility should be considered when calculations are made to determine assets. If experience-rated premium refunds are expected, and if the policy year does not coincide with the plan’s financial year, the refunds due should also be reported as plan assets. This is done only when a determination is made that the refund will become due. Finally, it is assumed that all the calculations can be reasonably performed (965-310-25-3).

Calculating Plan Benefit Obligations

965-30-35-1: All benefit obligations for single-employer and multiple-employer defined benefit health and welfare plans should include the actuarial present value of

• Claims payable

• Claims incurred but not reported (IBNR)

• Premiums due to insurance companies for accumulated eligibility credits and for postemployment benefits, net of amounts currently payable, and IBNR claims. This should be premiums for retired plan participants, including beneficiaries and covered dependents, for other plan participants eligible for benefits, and for plan participants not yet fully eligible. Information elements need to be in the body of the financial reports and should not be footnote disclosures.

Claims Incurred but Not Reported (IBNR)

An important concept that affects the actuarial valuation of plan assets and liabilities is the IBNR (claims incurred but not reported).6 According to HealthDictionarySeries.com, an IBNR claim signifies healthcare services that have been rendered but not invoiced or recorded by the healthcare provider, clinic, hospital, or any other health service organization. IBNRs are usually an integral part of a risk-adjusted contract between managed care organizations and healthcare providers. An IBNR claim refers to the estimated cost of medical services for which a claim has not been filed. These claims are normally monitored by an IBNR collection system or control sheet.

6 Adapted from a blog authored by Dr. David Edward Marcinko, “What is an IBNR medical claim?” Blog: Medical Executive Post ... Insider News and Education for Doctors and Their Advisors, October 2008, http://medicalexecutivepost.com/2008/10/07/what-is-an-ibnr-medical-claim/.

More formally, IBNR is the financial accounting of all services that have been performed but because of a time element or a “lag” have not been invoiced or recorded as of a specific date. The transactions covering medical services that were provided should be accounted for using the following IBNR entry:

Debit—Accrued payments to medical providers or healthcare entity

Credit—IBNR accrual account

An example of an IBNR in a hospital is a coronary artery bypass surgery for a managed care plan member. The surgeon or healthcare organization has to pay for all related services, such as physical and respiratory therapy, rehabilitation services, drugs, and durable medical equipment [DME] out of a future payment fund. These payments are contractual obligations (liabilities).

The health plan might not be completely billed until several weeks, months, or quarters later or even further downstream in the reporting year after the patient is discharged. To accurately project the health plan’s financial liability, the health plan and hospital must estimate the cost of care based on past expenses.

Since the identification and control of costs are paramount in financial healthcare management, an IBNR reserve fund (an interest-bearing account) must be set up for claims that reflect services already delivered but, for whatever reason, not yet reimbursed.

From the accounting point of view, the IBNR needs to be accrued as an expense and a short-term liability for each fiscal month or accounting period. Otherwise, the organization may not be able to pay the claim if the associated revenue has already been spent. The proper handling of these “bills in the pipeline” is crucial for proactive providers and health organizations. IBNRs are especially important with newer patients who may be sicker than prior norms. Amounts that hospitals hope to recover (recoverable) are posted as part of their reserve charges. In many cases, these recoverables end up being IBNR losses. They are recorded as IBNR claims on the balance sheet. When these book losses start becoming actual losses, the hospital might look to the insurer to pay a part of the claim. This might end up being a disputable charge.

For self-funded plans, the IBNR cost should be measured at the present value of the plan’s estimated ultimate cost of settling the claims. Estimated ultimate costs should reflect the plan’s obligation to pay claims to or for participants (for example, continuing health coverage or long-term disability) regardless of employment status and beyond the financial statement date if stipulated (965-30-35-1A).

Other Benefit Obligations

• Administrative expenses incurred by the plan can be recognized by including the estimated administrative expenses in the benefits expected to be paid or by reducing the discount rate (965-30-35-2).

• Postretirement retirement benefit obligations should be measured as the actuarial present value of future benefits that are tied into the participant’s service performed as of the cost measurement date. The calculation should be reduced by projected future contributions from plan participants. The determined calculation represents the employer’s funding requirement and the accumulated plan assets. This calculation should also consider the following variables:

• Continuity of the plan.

• That all assumptions made about future events for the calculation will indeed be met.

• Any anticipated forfeitures and integration with other plans.

• The discount rate used assumes a rate of return that matches the rates of return for high-quality fixed-income investments.

• Any insurance premiums paid for plan participants who have accumulated enough eligibility credits or hours of employment. This is usually calculated by multiplying eligibility credits by the current insurance premium and for self-funded plans by using the average of benefits per eligible participant. Mortality, expected employee turnover, and other required assumptions should be considered in the calculation.

• Any additional premiums as a result of the loss ratio exceeding a preset percentage.

• Additional payments to insurance companies resulting from stop-loss arrangements (965-30-35-9 and 965-30-35-12).

Additional Obligations for Postretirement Health Plans

If a benefit is provided for as part of a postretirement health plan, the estimated payments to participants needs to be accounted for. These benefits usually trigger on the retirement date, or sometimes these benefits trigger at a certain age. The calculation of the estimated obligation as of a given date is based on an actuarial present value of all future benefits that can be attributed to the participant’s period of employment. Benefit recipients should cover (1) retirees, (2) a terminated employee, if benefits have been earned, (3) a beneficiary or a covered dependent, and (4) and active participants, their beneficiaries, and any covered dependents.

Benefit obligation calculations need to include the following assumptions and calculation elements:

• Appropriate discount rates to account for the time value of money

• Per-capita cost of claims by age

• Healthcare cost trends

• Current Medicare reimbursement rates

• Retirement age

• Dependency status

• Mortality

• Salary progression

• A probability of payment calculation

• Participation rates

Benefit obligations should not include death benefits that might need to be paid during a participant’s active service period. This benefit obligation generally is determined by applying current insurance premium rates or, for a self-funded plan, the average cost of benefits per eligible participant. In either case, the calculation should consider assumptions on mortality rates and the probability of employee turnover (965-30-35-15 to 22).

Self-Funding of Health Benefits

One major financial issue of employer-provided health and welfare plans is the self-funding of these plans. In a self-funded health plan, the employer funds the plan from the company’s general funds instead of buying an insurance product.

With the cost of healthcare soaring over the past many years, employers look for ways to bring these costs down to ensure corporate profitability. Self-insuring health plans, rather than purchasing them from insurance companies, was recognized as such an opportunity.

Companies can pay the claims submitted under the plan by using a pay-as-you-go process. When employee claims come in and are reviewed and audited as eligible claims under the terms of the health plan, the employer pays the claims from general funds. Or the employer could set aside funds for use by this self-funded health plan and pay eligible claims from the set aside funds.

There is no insurance element here except that this arrangement can be considered as the company insuring itself. By way of contrast, an insured plan is one where the insurance company pays the claims, and the employer regularly pays the premiums to the insurance company. The premiums set by the insurance companies are adjusted each year based on the past-year usage experience of the insurance plan. Note that medical premiums and total healthcare costs have been the highest inflation-affected cost element in the whole market basket of goods and services within the Consumer Price Index sector of the economy.

Another point to note here is that the company will usually engage, on an annual fee basis, a TPA to administer the claims that come in for payment under the company’s self-insured employee health plan. The claims processing part can be a time-consuming effort, and so companies often outsource this activity to a knowledgeable external third party.

ERISA and Self-Funding

The Employee Retirement Income Security Act (ERISA) encouraged the growth in self-funded plans. ERISA covers all employee benefit plans sponsored by an employer. This includes employee pension plans and employee welfare plans. However, the emphasis of ERISA is on pension plans. Employee welfare plans include any nonpension employee benefit, including health plans, life insurance, and disability plans.

The key provisions of ERISA that relate to health plans are found in Section 514. This is known as the “preemption” clause, which states, “The provisions of this title and Title 4 shall supersede any and all state laws insofar as they now and hereafter relate to any employee benefit plan.”

Under Section 514, all private-sector employer-provided health plans are ERISA plans and therefore exempt under the preemption clause from state regulations. ERISA exempts self-insured plans from providing state-mandated benefits and from paying state premium taxes because the employers offering them are not considered to be in the business of insurance. But ERISA does not prevent state regulation of insurance. States therefore can and do regulate health plans covered under insurance contracts. This is one factor that encourages self-insurance.

To avoid state regulations of the employer-provided health plans, a company can set up the plan as a self-funded plan; in other words, they self-insure the plan. The employer now assumes the risks of the health plan. In the insured plan, the insurance company bears the risks of the plan. Bigger companies have the financial resources to take on additional financial risks that comes with self-insurance and at the same retain their capital rather than passing it onto insurance companies by way of premiums.7 The stable claims experience from year to year, due to the large employment base, also enables large businesses to safely assume the financial risk.8

7 Scammon. D.L., “Self-funded health benefit plans: Marketing implications for PPOs and employers.” Journal of Health Care Marketing, 9 (1): 5-14.

8 Park, Christina, H., “Prevalence of Employer Self-Insured Health Benefits: National and State Variation,” Medical Care Research and Review, Vol. 57, No. 3, September 2000, p. 342; Sage Publication, Inc.

So, as indicated, the term self-funding can indicate that the employer sets aside the money to pay the claims. Quite often, however, the employer sets up a pay-as-you-go arrangement, funding the claims from general funds. Nevertheless, hybrid arrangements can be set up, with self-funding as a primary feature.9

9 EBRI Databook on Employee Benefits, Chapter 28, Employee Benefits Research Institute, update March 2008.

In some cases, the companies might choose to carve out certain elements of the health plan and buy an insurance contract to cover those elements. The other remaining elements would then be paid from general funds, again on a pay-as-you-go basis. Typically, these carved-out elements could be related to mental health or prescription drugs. The carved-out segment then can be regulated by state insurance regulations by those states where the benefits are being paid.

Another funding mechanism is the purchase of stop-loss coverage. This is usually done to provide coverage for catastrophic losses. There are usually two types of stop-loss coverage:

• Insures against the risk that any one claim will exceed a certain amount

• Aggregate stop-loss, which insures against the entire plan’s losses exceeding a certain amount

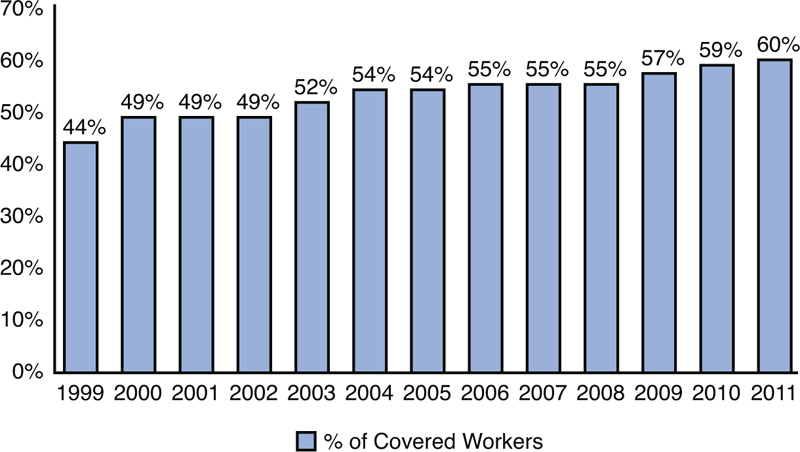

In their 2011 annual report on employer health benefits, the Kaiser Family Foundation and Health Research and Educational Trust provided the data shown in Exhibit 8-1 on the prevalence of self-insured health plans.

Exhibit 8-1. Percentage of Covered Workers in Partially or Completely Self-Funded Plans, 1999–2011

Source: Employer Health Benefits Survey, 2011, The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation and Health Research & Educational Trust, September 2011.

International Financial Reporting Standards and Employee Health and Welfare Plans

In the IFRS, the accounting for employee benefits is addressed in IAS 19, Employee Benefits. This section covers provisions in IAS 19 that affect employee benefits items only. Note that IAS 19 also covers items that are termed employee compensation for the purposes of the book. The main provisions of IAS 19 that affect employee benefits are as follows:

• Short-term benefits: Benefits payable within one year. The employee will have to have been provided the services for which required compensation has been earned. These items cover medical benefits provided to regular employees, vacation and sick pay, as they relate to the employee benefit categorization. IAS 19 requires that the undiscounted amount of these benefits expected to be paid, after the service has been rendered, should be recognized in that period.

• Postemployment benefits: Benefits that are payable after the employment term is completed. These benefits include pensions, retiree health benefits, life insurance, and the continuation of medical and life benefits after employment. No termination benefits are included in this category. In this category, IAS 19 states that if the benefit program is a defined contribution plan, the costs need to be recognized in the period the contributions are made in exchange for employee services during that period. For defined benefit plans, the amount recognized in the balance sheet needs to be the present value of the defined benefit obligation, as adjusted for unrecognized or actuarial gains or losses. Also included are unrecognized past service cost for pension plans (see Chapter 10). The balance needs to be reduced by the fair value of plan assets at the balance sheet date.

• Termination Benefits: Benefits paid upon involuntary termination or a voluntary termination where compensation has been paid for a temporary period.

For termination benefits, IAS 19 specifies that amounts payable should be recognized when the company has made a decision to either terminate the employment of an employee or group of employees before the normal retirement date or provide termination benefits as a result of an offer made to encourage voluntary terminations.

Under IAS 19, the company has to show that the planned termination is being done within the terms and provisions of a formal written plan and that the company does not plan to cancel the plan after the termination action has been taken. IAS also allows discounting of termination action costs when 12 months have expired from the balance sheet date and the benefits are currently being paid.

The Financial Reporting of Employee Benefit Plans

The financial reporting for employee benefit plans cover reporting requirements for defined benefit and defined contribution plans health and welfare plans. The reporting standards for these plans have components that are similar in nature.

ERISA requires many different reports be prepared and filed annually. These reports need to be prepared and filed with the Department of Labor and provided to plan participants, plan beneficiaries, and others. ERISA requires the report filing, but the Department of Labor (DOL) regulations define the filing requirements.10

10 Doran, Donald A., and Verrekia, JulieAnn, “Employee Benefit Plan Accounting & Reporting,” Chapter 41, The Handbook of Employee Benefits, Edited by Larry S. Rosenbloom, 2001, McGraw Hill, New York.

DOL requirements stipulate the filing of Form 5500, with attachments, every year. The attachments include financial statements, notes, supporting schedules, and an accountant’s report.

SFAS No. 35 requires that every plan issuing financial statements distribute, at the end of each year, a statement of net assets available to pay out plan benefits. A statement of the changes in net assets for the year ended also needs to be developed. Related notes need to be filed, as well, as part of the financial statements.

The financial statements presented need to be a comparative form (that is, a year-to-year comparison). The statements have to be prepared under GAAP principles, which mean the use of accrual accounting. Under the accrual basis, the purchases and sales of securities must be recognized on a trade date basis rather than a settlement date basis.

Statement of Net Assets Available for Plan Benefits

Because plan investments are usually a plan’s biggest asset, the valuation of those plan assets is particularly important. Most plan investment assets are reported using a fair value concept.

In accounting, the fair value is usually the value that can be expected in a transaction between a willing buyer and a willing seller. For securities traded on an active market, the fair value is the quoted market price. For assets for which there is no quoted market price, alternative valuation methods need to be used. A commonly used method is the discounted cash flow (DFC) method.

Contracts with insurance companies need to be valued differently. Valuation of investment contracts with insurance companies for health and welfare plans and defined-contribution plans is governed by AICPA’s SOP 94 – 4: Reporting of investment contracts held by health and welfare benefit plans and defined contribution pension plans. The AICPA requires that most plan contracts be valued at fair value, except contracts that incorporate mortality and morbidity risk or those that allow for withdrawals for benefits at contract value. In these cases, the contract can be reported at contract value.

It also depends on whether the payment to the insurance company is allocated to purchase insurance or annuities for the individual participants or whether the payments are accumulated in an unallocated fund to be used to pay retirement benefits. These are referred to as allocated and unallocated arrangements.

In allocated funding arrangements, the insurer has a legally enforceable obligation to make benefit payments. The obligations of the plan may have been transferred to the insurer through the payment of premiums. Payment of a premium where the risk is transferred to the insurance company represents a reduction in the net plan assets. So, for plan reporting purposes, the investments in the allocated insurance contract should be excluded from plan assets.

Unallocated funds are included in plan assets.

Premiums paid that represent deposits should be reflected as plan assets until such time as the deposit is refunded or are used to pay claims. Insured plan claims reported and claims incurred are the obligations of the insurance companies and do not therefore need to be reported. However, this is not the case in self-insured plans. So in these plans, the claims need to be reported. The footnotes should disclose significant assumption changes used to determine plan liabilities.

Often, funds for reporting purposes are commingled trust funds, pooled separate accounts of insurance companies, or master trust funds containing assets of two or more plans pooled for investment purposes. Common or commingled funds are generally for two or more companies. Master trusts hold assets for a single employer or for members of a controlled group.

For reporting purposes, the value of funds is based on unit value of the fund or the separate accounts that need to be reported at fair value. The specific portion of interest of the plan in the master trust needs to be reported as a separate line item. The net change in fair value of each significant type of investment of the master trust, the total and net investment income, the method of determining fair value, the general type of investments, the basis used to allocate net assets, gains and losses to participating plans, and the plan’s percentage interest in the master trust should all be reported in the footnote.

The general disclosure requirements for the statement are

• Whether fair value was measured using quoted market prices in an active market or an alternative method was used.

• The method of valuation.

• Detail of the investments must be provided either on the face of the statement of net investments or in a footnote.

• Investments must be segregated by types, such stock, bonds, and so on.

• Investments representing 5% or more of net assets available for plan benefits must be reported separately.

Receivables must be reported separately for employer contributions, participant contributions, amount due from brokers for securities sold, and accrued interest and dividends.

Contributions receivable must report only those that are receivables as of the date of the report. Participant contributions are usually those that are payroll withholdings that have yet to be remitted to the plan. Supporting documentary evidence for employer contributions must be provided. Allowances for unaccountable receivables need to be established as per normal accounting practice. This becomes imperative considering that troubled companies might not have the ability to make the necessary contributions to the plan. Under these circumstances, the receivables need to be reduced by the uncollectible offset. Explanation for this probability should be disclosed in the footnotes. Finally, any deficiency in the funding status of the plan should be recognized as a receivable.

Statement of Changes in Net Assets Available for Plan Benefits

Significant changes in net assets during the reporting period need to be disclosed. The net appreciation or depreciation includes realized gains or losses from the sales of investments and unrealized gains. Losses from market appreciation should also be disclosed. The separate disclosure is required by ERISA. But, the realized or unrealized gain or loss needs to be based on the value of the asset at the beginning of the plan year and not the historical cost of the asset.

Additional General Disclosure Requirements

• A description of the plan, including vesting and benefit provisions, significant plan amendments during the year, and the policy regarding forfeitures

• The fund’s funding policy along with changes made during the year

• Plan policy regarding the purchase of allocated insurance contracts that are excluded from plan assets

• Actuarial assumptions and any changes made to these assumptions during the year

• The federal tax status of the plan, including any IRS determination letters received

• Significant transactions with interested parties such as plan sponsor, plan administrator, employees, or employee representatives

• Significant events or transactions that happened during the plan year

• Accounting policies that differ from GAAP

• Commitment and contingencies

• Significant risks, uncertainties, and estimates used

• Information on off-balance sheet risks of accounting loss and the significant concentration of credit risk

• Facts on any investments in derivative financial investments

• Differences in amounts reported in financial statements and those reported in DOL Form 5500

Additional General Disclosure Requirements for Health and Welfare Plans

The general disclosure requirement for health and welfare plans are as follows:

• The organization’s policy with regard to participant contributions to the plan

• The actuarial assumptions used to calculate plan benefit obligations and actuarial assumptions changed during the current plan year

• The method of funding plan benefits, if there are fund deficits

• The types and extent of insurance coverage that transfers risk from the plan

• The healthcare cost trend rates used to calculate cost of benefits

• For postretirement benefit plans, the effect of a percentage point increase in assumed healthcare cost trend

Key Concepts in This Chapter

• FASB 965 – Employee Benefits

• The standards framework

• Defined-contribution health and welfare plans

• Defined-benefits health and welfare plans

• Claims incurred but not reported

• Postretirement health plans

• Self-funding of health plans

• ERISA and self-funding

• International Financial Reporting Standards – IAS 19

• Financial reporting of employee benefit plans

• Statement of net assets available for plan benefits

• Statement of changes in net assets available for plan benefits