9 conceptualization

developing ideas

Regardless of toots and delivery,format,concept development is critical to all forms of graphic communicatin.Since the beginning of the twentieth century,artists have expressed their ideas through the medium of animation. In more recent years,graphic designers have harnessed the devices of time and motion to convey their ideas in movie titles, network identities, Web sites, multimedia presentations, and environmental graphics. In the past, developing concepts to communicate their ideas was the first challenge. The current challenge is developing unique concepts and communicating them by storytelling.

“Creation is the artist’s true function. But it would be a mistake to ascribe creative power to an inborn talent. Creation begins with vision. The artist has to look at everything as though seeing it for the first time, like a child. ”

— Henri Matisse

“The greatest art is achieved by adding a little Science to the creative imagination. The greatest scientific discoveries occur by adding a little creative imagination to the Science. ”

— James Elliott

Assessment

defining the objective

Every design begins with an objective. Without a clear objective, your ideas can become lost in the ocean of right-brained activities. Before plunging back into the creative waters, it is best to clearly define your objective on paper without a lengthy narrative.

Coming to terms with a project’s objective may take time. Once it is established, it should be kept in mind from conceptualization through design to the final execution.

targeting the audience

The goal of visual communication is to facilitate a reaction from an audience, and this audience should be clearly defined in order to meet your objective. In the industry, the individuals who are involved in marketing usually have already achieved this, although designers have been known to play a strong role in identifying the audience.

researching the topic

Research is key to effective communication. Intriguing concepts and cutting-edge design may not be enough to effectively communicate the information if adequate research is not conducted ahead of time. Diving into the creative waters too soon poses the danger of time and energy being wasted on ideas that may be dynamic but are irrelevant or inappropriate to the project’s objectives. Therefore, a thorough analysis of your subject matter should occur before you begin to conceptualize.

Clients can mistakenly assume that the designers are well informed about the topic being considered. This can be dangerous to both parties. Therefore, it is wise to step up to the plate and assume the responsibility of educating yourself about the subject at hand. A wide range of resources are available to aid in your investigation. Many consider the Internet to be the quickest method of digging for information. Others find the library to be the most efficient resource. Setting up a meeting to discuss the material with the client first-hand is, of course, highly recommended, since he or she will be the most valuable source of information. There is nothing wrong with asking too many questions. The more thorough your research, the more effective your design.

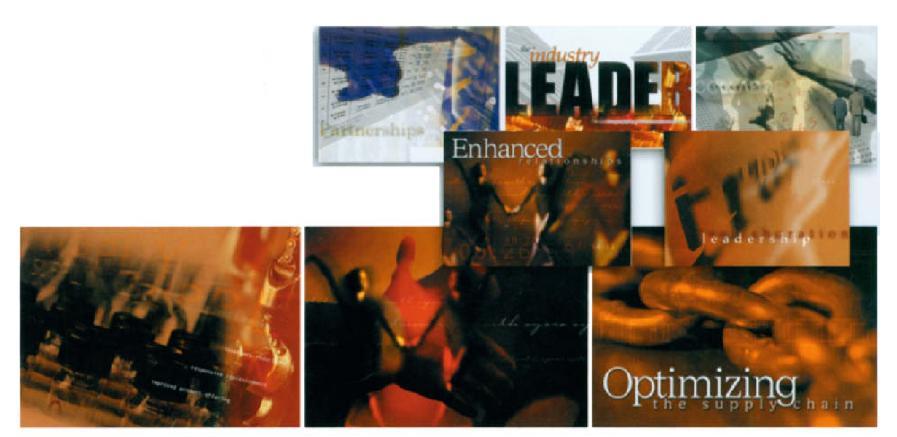

9.1 Concept sketches for a trade show video, by Jon Krasner. Courtesy of Syncra Systems, Inc. and Corporate Graphics.

The metaphors used here came as a result of educating myself about supply chain management

understanding the restrictions

The most successful graphic designers aspire to exceed our own potential. Passion for creativity drives them to become better at what they do. They create art not because they want to, but because they have to in order to feel personally rewarded. However, the industry poses certain restrictions that they need to be aware of.

Budgetary constraints can limit the use of materials, equipment, and reliable technical support and prohibit hiring outside photographers or purchasing as many stock images or video clips as they see fit.

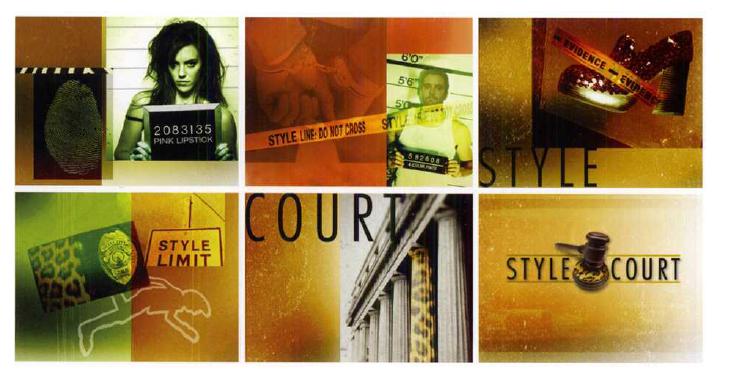

Regardless of how unreasonable deadlines may appear, designers are forced to be realistic about what can and cannot be accomplished within the given window of time that is available. For example, After E! Networks declared the need for a show opening for Style Court less than three weeks before airing (after spending many weeks looking through hundreds of static logo designs to choose the show’s identity). Designer Susan Detrie was put to the test with a time frame of under forty-eight hours to develop a storyboard. A combination of quick thinking and late evening hours resulted in an engaging board that, like the show’s content, presents a variety of images that reflects the show’s entertaining nature and wide range of ages. Humorous court icons, such as a bad hairdo, a leopard skin suit, and an evidence bag consisting of 1970s platform shoes, create a feel similar to that of a generic police show, such as NYPD Blue (9.2).

“With creative freedom, time, money, and reliable technical support, the potential here is limitless. Just imagine the possibilities!”

—Jon Krasner

“Better to have the creative reins pulled back than to be kicked in the flanks for more!”

—Meagan Krasner

9.2 Storyboard for a show open to Style Court. Courtesy of E! Networks and Susan Detrie.

The opinions and biases of clients can also be creatively restricting. Clients are not always open to new ideas (even if they say they are). It is seldom that designers are given complete artistic freedom. Some clients may seem utterly inflexible and closed-minded, while others, unintentionally, attempt to play the role of art director or “creativity gatekeeper.” Because the client controls the paycheck, the portfolio, and to an extent, a designer’s reputation, pride that is built on years of educational training may have to be swallowed in order to conform and keep your client satisfied. The majority of the time, solutions are usually mutually agreed upon between the client and designer from initial concept to final completion.

These restrictions should not be perceived as limitations to creativity, but rather, as guidelines to help give your ideas direction.

considering image style

There are several types of images to choose from including photographic, typographic, illustrative, abstract, and so forth. These image categories can take on different visual styles from graphic, to textural, whimsical, sketchy, or blended, to name just a few. Techniques, such as cropping, lighting, distortion, color manipulation, deconstruction, layering, masking, and special effects, can enhance the expressive properties of your content before it is integrated into a storyboard.

The stylistic “flavor” of the visuals-both images and type-depends on your underlying theme or message, whether it is marine, sports, rock ‘n’ roll, theatre, country, cultural, or eclectic. A figurative interpretation of a concept may require the use of metaphorical imagery, while a different set of images may be more appropriate for a more literal interpretation. The content should also reflect the demographics of the target audience, whether they are artists, yuppies, teenagers, or professionals. These factors should be considered as early as possible.

9.3 Frames from “Planted,” a motion identity for CapacityTM motion design studio.

The metaphor of seeds being planted to grow into something beautiful expresses the concept of running a creative business.

Formulation

Once the objective, target audience, and restrictions have been defined and the subject has been thoroughly investigated, the floodgates of creativity can be opened to allow imaginative ideas to pour forth.

brainstorming

Brainstorming is the first step in generating ideas. It works best in an environment that is conducive to creative thought. Annoyances, such as junk e-mail, uncooperative technology, and telephone sales calls, are detrimental to brainstorming. Therefore, scheduling a continuous block of time to think quietly without distractions is recommended. Some people react well to background music while others require complete silence in order to concentrate.

All concepts begin in the imagination. As they enter, they should be recorded immediately. It is wise to have a sketchbook handy to capture the spontaneous flow of ideas. Putting pencil to paper is an invaluable process that, like music improvisation, keeps ideas fresh and moving. Pencil sketches (or thumbnails, as they are often referred to in print design) are usually where the design begins to take its form. These should be small and loose, allowing for the quick generation of ideas. Spending too much time polishing a sketch can break creative momentum. Many designers prefer to work out their initial concepts in a more polished, digital format, because the results more closely resemble the final storyboard and the later production.

“An idea is a point of departure only. As soon as you elaborate it, it becomes transformed by thought.”

—Pablo Picasso

9.4 Concept sketches for “lcarus.”Courtesy of Adam Scwaab.

9.5 These early digitally-executed ideas explore how Adobe’s multidimensional logo could be potentially animated. Courtesy of twenty2product.

obstacles to creative thinking

Every person experiences moments when they have a mental block that prevents them from creating at their maximum capacity. Although the ability to create cannot be turned on or off at a whim, being aware of obstacles that impede creative thinking is the first step in avoiding them. For example, it’s easy to become lured into stylistic trends that have been overused. Biased notions and contrived ideas of what’s “hot” can limit the range of creative opportunities and prevent you from being original. Being aware of trends in the industry is healthy, as long as your design does not become reliant on them. The range of digital effects that are available can also intrude on creative thinking, since they require minimal artistic skill or sophistication. Although they can be beneficial when used intentionally, they lack ingenuity, and their ease of use can impede imaginative thinking and obscure aesthetic judgment. The abundance of stock photography, illustration, fonts, and clip art makes it easy for designers to rely on ideas relating to popular culture rather than on their own capacity to conceptualize. Last, the demand for acquiring technical proficiency, due to the rapid pace of software development, can be an impediment to creativity. It is important to not lose sight of your primary goal as a designer.

9.6 These digitally-executed sketches for Fuel TV’s signature network ID are based on the fictional character, “Poopa-Ooba,” a demigod who invented Skatism as a culture and religion for skateboarders. Courtesy of FUEL TV.

*See DVD for final animation.

pathways to creative thinking

Creativity can be mistaken for originality, when in fact, very few original ideas exist. Many designers merge previous concepts in their own personal way. Creative designers, like laboratory scientists, trust their intuitions and are not afraid to face new challenges. Yet, the creative process can be elusive. Ideas sometimes spring up when we least expect them to. Inspiration, risk taking, and experimentation can foster innovative thinking and allow ideas to develop naturally.

inspiration

Inspiration is the motivating force behind innovation. Unlike a job that ends when the shift is complete, seeking out inspiration is a continuous process of searching for new angles and directions in an attempt to smuggle your ideas into each new assignment.

Artists often find inspiration in identifying with their subject. A student of mine chose to express the theme of domestic violence in a project based on visual metaphor. Based on her working with people who were victims of domestic abuse, she was able to relate to the psychological consequences that they faced; her emotional identification inspired her to develop genuine ideas. In an animation for a CD-ROM mailer, the topics of panic and disaster served as inspiration to market backup data software to protect important information from the possibility of a hard drive crash.) Panic was expressed from a physiological standpoint through images pertaining to physical and emotional responses that occur during times of stress or fear. Disaster was communicated through images of natural phenomena such as tornadoes and floods. These themes served to create an entertaining presentation that viewers could experience before interacting with the program (9.8).

9.7 Sketches for a sting entitled Hero Stereotype by Megan Mock, University of San Francisco, Professor Ravinder Basra.

9.8 Frames from an opening to a CD-ROM mailer for Accurate Data. Concept and design by Jon Krasner. Courtesy of Belden- Frenz-Lehman. Inc.

The capacity to identify with your subject, however, does not always come naturally. In most cases, it occurs after conducting adequate research. In 2000, twenty2product was asked by RockShox, a leading company in the global cycling community, to develop concepts for a Web site and trade show video. After becoming familiar with the cycling industry, twenty2product developed an appreciation for the mechanical know-how involved in designing bicycle parts. Technical machine drawings became a source of inspiration and were used to inform the look and feel of the graphics. Complex diagrams, abstract graphic patterns, typography, and live-action footage were integrated into a highly compelling series of sketches that conveyed forward thinking, the millennium, and all of the things that it implied (9.9).

9.9 Web site sketches for RockShox. Courtesy of twenty2product

Be open to ideas from almost any source—magazines, books, films, etc. Involving the client may reveal that you are not an incredible walking idea factory; however, ideas that formulated through collaboration may be more beneficial than those that are generated in isolation. Observing the work of other designers and design movements can also help foster new ideas. This should be exercised with moderation, since relying too greatly on other styles can be dangerous.

9.10 Frames from a political evening program for the Franco-German culture orte. Courtesy of Velvet. (*Also see Chapter 5, figure 5.18.)

The antique Greek drama of Ariadne and Theseus served as an inspiration for the central theme. Two elements from the story, a labyrinth and a ball of yarn, establish the context of political entanglement. The body movements and gestures of the actors symbolize puppets being pulled on a string and the masters who pull the strings.

risk taking

Throughout history, stylistic movements in art and graphic design were manifested from groundbreaking visionaries and experimenters who deviated from the norm. Fauvist painters were referred to as “wild beasts” by virtue of their garish color combinations and harsh, visible brush strokes. Their work eventually became celebrated and absorbed into impressionist painting. David Carson took risks by ignoring the conventions of print and introduced a broad spectrum of innovative design solutions to Ray Gun magazine. Although his style was rejected, it eventually became a milestone in print design and gained popularity among a fast growing audience. The rebellious nature of designers who were hired by MTV challenged the conventions of corporate identity by introducing an entirely new edgy style that eventually spawned new approaches to broadcast animation for channels such as CNN, VH1,

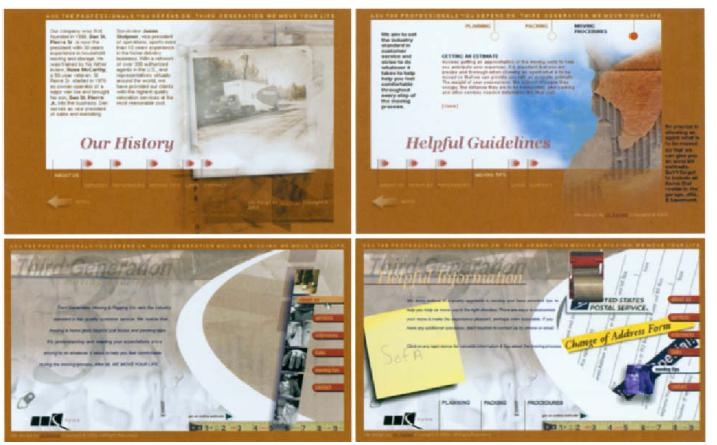

9.11 Html and Flash Web site pages. Concept, design, and animation by Jon Krasner. © AML Moving & Storage.

Pride in workmanship and family traditions served as inspiration; for these designs.

and Nickelodeon. These individuals did not gain artistic satisfaction from following the same design recipe; rather, they broke out of their safe, cozy territories to embrace and celebrate the power of imagination by keeping an open mind and considering unexpected ideas.

Taking risks means venturing into new, unfamiliar territory. This may feel uncomfortable because of the potential dismissal of an idea by traditions served as inspiration; for these designs. your client or audience. (Realize that you can always fall back on an alternative, perhaps less radical, approach.) Despite the level of discomfort, applying the same formula time after time can become intellectually dull, and your creative resources can become stale if you remain on a plateau for too long. The consequences of not being accepted by the mainstream are worth your chance of discovery.

experimentation

Like science, artistic concepts are based on an evolution of discovery through experimentation. Experimentation contributes to ideation by opening up your thought processes and eliminating contrived or trendy solutions. It relies on the element of play and embraces the unexpected, allowing accidents to become possibilities. New discoveries can lead to sophisticated approaches to problem solving. Further, experimentation gives you the opportunity to attain individuality. Since risk taking is involved, experimental play is not intended to produce mediocrity; rather, its goal is to make life less predictable.

“In traditional design you learn from accidents: You spill paint and come up with something better than what you intended. The same thing happens on the Mac: You go into Fat Bits, see a pattern, and say, ‘Ah, that looks better than the original!’”

—April Greiman

A friend of mine once defined art as “studied playtime.” In order to maintain that state of mind and keep the pathways to creativity open, take the “scenic route” and allow your mind to wander. Stay alert to the possibility of serendipity. If you find yourself coming back to an idea that lacks ingenuity, revisit it later from a fresh perspective.

Cultivation

Once ideas have been formulated, they must be cultivated to mature properly, just as a garden must be cultivated by fertilizing, weeding, and watering to produce a successful harvest.

evaluation

Once your concepts are generated through brainstorming, evaluating them objectively helps you decide what to keep and what to discard before plummeting into production. This involves reconsidering the concept’s appropriateness with respect to the project’s goals. Questions to ask youself at this stage are:

1. Will my concept capture and hold my audience’s attention?

2. Is this idea based strictly on technique or trend?

3. Is this concept different enough from what has already been done?

4. Is this concept realistic enough to implement technically?

5. Will the means needed to implement my idea fit within the budget?

selection

Once evaluation has taken place, the process of selection begins. On a positive note, you get to make the first cut before the client begins his or her jurying process. Although it can be painful to let go of invigorating ideas that may be more appropriate for another project, presenting too many concepts can be counterproductive. Consequently, the client can develop the expectation that you will always provide numerous possibilities for every project. Relinquishing this much creative control to the client can result in him or her choosing a concept that you do not strongly support. In your absence, bits and pieces of your ideas may be mixed and matched in a way that is not in line with your thinking. Further, the opinions of other coworkers not involved in the project may be taken into consideration; such uninformed input can be detrimental to what you are trying to accomplish. Therefore, it is in your best interest to be discriminating and submit only the concepts that, in your opinion, are the best.

clarification and refinement

Depending on the client’s and test audience’s response, your concept will most likely require further clarification. Pencil thumbnails may not adequately describe your idea in visual terms. More finished roughs should give a clearer representation of the visuals and typography, compositional treatment, and motion strategies. Techniques such as collage, photomontage, and photocopying allow quick composites to be generated. A wide range of natural media, including brush, marker, and colored pencil, can also be used to introduce color and texture. Digital refinement can offer a degree of polish. Depending upon the scope of your project, it may be necessary to go a step further and develop motion tests to resolve how elements will move and change ahead of time. Additionally, the client is able to experience the kinetic quality of the concept before production, allowing him or her to give approval and provide feedback early on.

9.12 A series of motion studies for Adobe’s Expert Support trade show offered ways that the components of the Adobe logo and titling could be animated in an orthographic space with a flattened perspective. Courtesy of twenty2product. Copyright 2004 Adobe Systems.

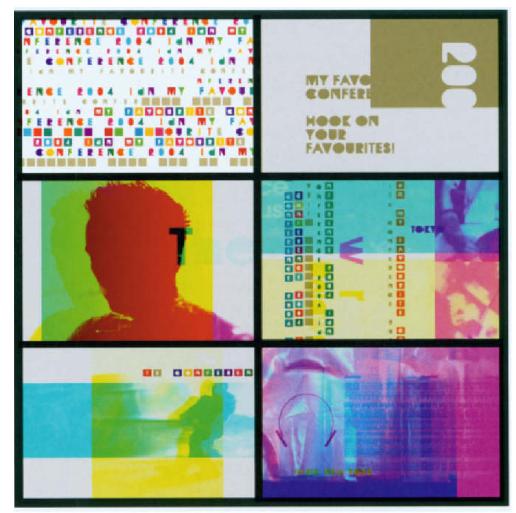

In 2004, twenty2product developed a set of motion tests to be used for a looped opening animation sequence to “My Favorite Conference,” a large-scale trade show in Singapore (9.13). This event was sponsored by IdN, an international publication for the design community in AsiaPacific and other parts of the world. Similar to Macworld, the event was dedicated to the merging of different graphic design disciplines to give rise to unique creative and contemporary insights. The goal of the opening sequence was to introduce topics to be presented at the conference and acknowledge the individual speakers and corporate conference and acknowledge the individual speakers and corporate sponsors. Terry Green, creative director and co-founder of twenty2product, refers to these segments as “ artifacts ” of their working process that may or may not appear as a layer in the final composition. Working in this manner helped move ideas forward.

9.13 Frames from motion sketches for “My Favorite Conference.” Courtesy of twenty2product. Copyright 2004 IdN, all rights reserved.

9.14 This set of motion tests were used in a music video for Susumu Hirasawa, a Japanese electropopartist, known in Western cultures for his anime soundtracks.They were also used in a promotional spot for Santana Row, a premier retail and entertainment complex in San Jose, California. Courtesy of twenty2product.

Storyboards

Once a concept has been clarified, refined, and has received client approval, the next stage of conceptualization involves storyboarding. In most cases, the storyboard is the final phase of conceptualization.

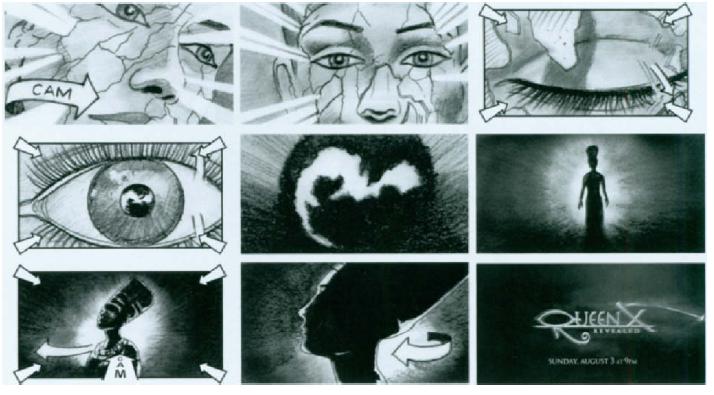

A storyboard is a cohesive succession of images (or frames) that provide a visual map of how events will unfold over time, identifying the key transitions between them. Sometimes accompanied by supporting text, it establishes the basic narrative structure of your concept. Figure 9.15 demonstrates a storyboard for Nefertiti Resurrected, aired on the Discovery Channel in 2003. According to Director Michael Middeleer of Viewpoint Creative: “We sought to demonstrate the beauty, drama and mystery surrounding Nefertiti and show how the Discovery Channel resurrects one of ancient Egypt’s most famous and powerful queens.”

Storyboarding requires preparatory mental visualization, since there are many factors that need to be determined, such as the types of visuals (images, typography, live-action footage) that will be used, the stylistic treatment of the visuals, types of motion and change, the spatial or compositional arrangement of the frame, and progressive or sequential aspects, such as transition, pace, birth, life, and death.”

9.15 Storyboard frames for Nefertiti Resurrected (2003). Courtesy of Viewpoint Creative and Discovery Channel

visual content and style

Traditional and digital artistic processes and media, including drawing, painting, sand, collage, and montage, can be used alone or in combination to support the image style that you choose. Images that are created in raster-based paint applications can yield a certain handexecuted or photographic look. Postscript graphics that are generated from vector-based programs can achieve a flatter, more stylized quality. If you are appropriating existing images (versus generating original artwork), pixel-based software, such as Adobe Photoshop or Corel Painter, offer a great deal of flexibility and control in image editing and manipulation.

Environmental or atmospheric conditions should also be considered. The background provides the setting or stage where events take place, and at this stage, the background should be developed and treated as an integral part of the piece. Background images can be moved or changed over time, or they can serve as unchanging backdrops against which the animations of foreground elements take place. In the three-dimensional environment, lighting, environmental effects (i.e., fog, water, and smoke), and camera views should be planned during storyboarding, since both play a significant role in establishing the atmosphere and perspective of a scene.

9.16 Storyboard design, by Justin Ruggieri, Kansas City Art Institute, Professor Jeff Miller.

This storyboard illustrates the concept of sociophobia—the fear of people or society. As the viewer looks out, he sees a highly abstracted cityscape with personified symbols walking by. The city’s buildings are layered with various words and phrases

pictorial and sequential continuity

The single most important measure of a storyboard’s effectiveness is its continuity. The pictorial continuity must indicate cohesion between the style of images and type, choice of color scheme, and treatment of compositional space. The sequential or progressive continuity between frames must be clear in order to convey a comprehensible and logical flow of events.

Pictorially, the style of the visuals should be coherent across all frames. The storyboard also should illustrate how elements will be organized spatially within the frame. For example, an organized pictorial space may enforce the movements of elements to adhere to an underlying grid. On the other hand, the motion of objects in a loose, free-flowing composition may produce a more random effect. Establishing a clear distinction between background and foreground elements can achieve a strong sense of spatial depth, while breaking traditional figureground relationships through heavy layering will flatten the space.

The arrangement of all elements, background and foreground, moving and nonmoving, changing and nonchanging, is critical in achieving the desired aesthetic effect with regard to the pictorial composition of the frame. Additionally, it helps determine the visual hierarchy of information on the screen. Careful thought must be given to maintaining a clear distinction between elements of varying importance by virtue of their relative sizes, color, duration, and positioning. Relationships between the image and typographic content and the edges of each frame should also be considered. These types of pictorial considerations are discussed in more detail in Chapter 7.

In addition to pictorial continuity, the storyboard should convey a basic sense of how elements move and change over time and space, as well as the methods in which they enter the frame and leave the frame. It should also clearly express a logical order of the key events, and the transitions between them should be cohesive and clear. This type of “orchestration” is a developmental process that requires strategic planning, unless your project calls for improvisation. (Chapters 5 and 8 discuss a variety of approaches to choreographing motion and time.)

9.17 Storyboard design by Mike Cena, Fitchburg State College, Professor Jon Krasner.

stages of development

early development

The execution of a storyboard can range from a series of quick sketches to a group of highly developed color images. Depending upon your own working process, the client’s demands, and other factors, such as budget and time, most storyboards go through several iterations before they are executed digitally to be presented to the client.

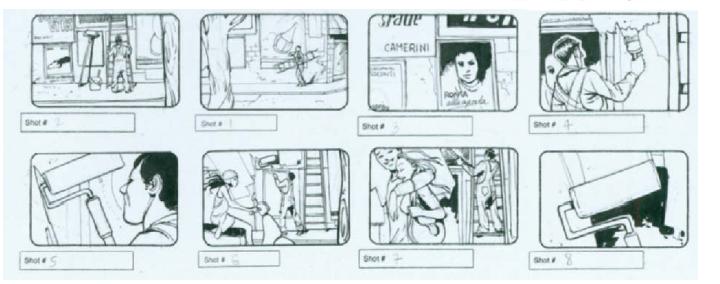

After your concept has been refined, it can be translated into an initial comprehensive—a series of quick, sequential drawings that have a 4:3 aspect ratio of a typical, rectangular frame. Here, you should divide your story into its major sequences and transitions, being aware of visual continuity. These small sketches will save you time later, since they can be changed easier than the enlarged, polished frames of a final comprehensive. Each scene can be individually worked out on a separate piece of paper and later rearranged or discarded once they have been analyzed. The quality of the drawings is not as critical as the flow of actions between the frames. In fact, dedicating too much time to making each image look realistic can sacrifice the most critical factor—continuity. Considerations such as the flow of actions or events from scene to scene, the clarity of transitions between the scenes, the approximate time it will take to animate the scenes versus the allowed time, and the resources needed to create the desired effects should be given careful attention during this stage of design.

Although there are cases when the initial storyboard sketch may look much like the final comprehensive, the client may never see it. In most cases, it allows you to evaluate the work solely on your own professional expertise. Keep in mind that there is room for further improvement, and several drafts may be necessary before arriving at the final storyboard. Evolution is the key to successful storyboarding. Creative ideas are meant to build upon one another over time.

9.18 Initial comprehensive sketch for SKY Cinema Italia’s Spazjo Itolio. Courtesy of Flying Machine.(*See Chapter 2, figure 2.56 for final animation frames.)

*See DVD for final composition.

This stage offers tremendous creative potential, allowing you to deviate from your original ideas. Elements may be altered, simplified, exaggerated, added, or deleted. Stay alert to the possibility of serendipity, since

9.19 below: Storyboard sketches for Nestle’s Wonka Egg Hunt. Courtesy of Shadowplay Studios (*See Chapter10, figure 10.13 for final animation frames.)

“happy” accidents can offer many creative opportunities. Do not go too far down a road with a concept before submitting a rough storyboard. The business risk may be too great to plunge into the waters too quickly. The client should be kept in the loop along the way in order to avoid too much time being spent on perfecting ideas, only to have them rejected later. Unless your concept has been accepted verbally or in writing (preferred), proceed with caution! Posting frames to the Web can save valuable time in getting approval.

the final comprehensive

Once your sketches have been revised, they should be reworked and edited down into a final comprehensive—a more refined series of frames showing major events, transitions, framing, and camera moves. These can be created on nearly any medium. Although hand-drawn artwork is sometimes still used, digital execution is the favored method of storyboard production today, since it is quicker than generating original artwork and may be more appropriate in representing the subject in situations where the visuals will be photographic. If time is a critical factor, stock photographs and illustrations are available online or by purchase of CD-ROM content by numerous suppliers. (You should carefully read the terms and conditions to avoid using materials illegally or without permission.)

brevity and clarity

The final comprehensive should be succinct, featuring only major events. Transitions between frames should be easily readable. Six to ten frames are typical for a 30-second spot, while a 1- to 2-minute movie trailer might require up to twenty frames. Station IDS and Web site introductions are usually presented in no more than eight frames.

9.20 Final comprehensive storyboard for Icorus. © Adam Schwaab

professionalism

Professionalism is critical to convincing the client (and yourself) to settle on an idea. Sloppy execution, lack of attention to detail, and ambiguity of presentation can create a negative impression.

Today, digital images, because of their degree of polish, are commonly used to generate final comps. The most impressive-looking boards are assembled from high-quality prints that are pasted up onto poster or bristol board. Supporting text can be added as a supplement; however, it should not be used as a substitute for a lack of clarity in the images. Including action-safe and title-safe borders on each image allows all parties to visualize the variable 10% perimeter of the frame.

Your finished storyboard should serve as a basis from which additional creative opportunities can be pursued. Although major decisions have already been worked out, there is room for experimentation and continued creative development during production (provided that the client has some degree of flexibility).

9.21 Storyboard for SKY Cinema Classics’ show opening. Courtesy of Flying Machine.

The doors of a darkened theatre open, allowing us to walk down the aisle to experience a melange of typography and cinematic imagery from historical moments, including a World War II fighter plane and a figure in a trench coat occupying the space around us. As the curtains draw open and the flickering projector brings the screen to life, the SKY Cinema Classics logo blazes across it.

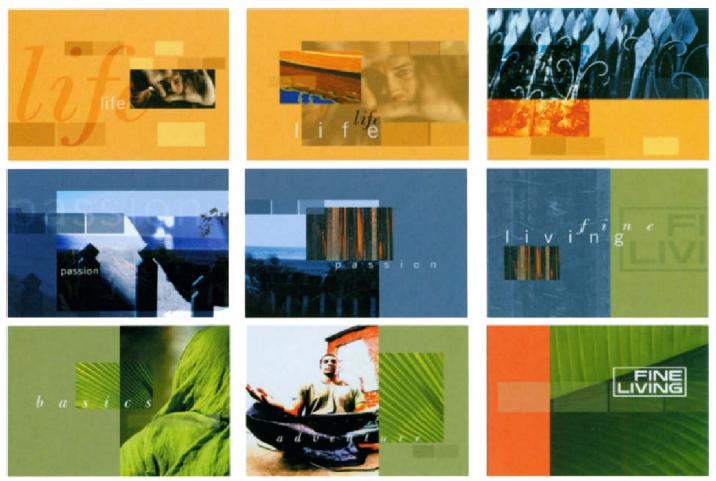

9.22 above: Storyboard for Fine Living Network. Courtesy of Another Large Production and Susan Detrie.

9.23 below: Storyboards from “Cowboy Transformation” and “Smoke” IDs. SKY Cinema. Courtesy of Flying Machine.

Animatics

Since storyboards describe motion in a static manner, animatics, or animated storyboards, are sometimes needed to pre-visualize and resolve the motion and timing of events. They take the art of storytelling one step further than storyboards by breathing life into the images and synchronizing their movements and transitions to sound. (For this reason, animatics are usually produced after the soundtrack has been created.) In some cases, the storyboard and soundtrack may be modified, and a new animatic may be generated, if necessary, until the storyboard is perfected.

Animatics have proven to be time and cost effective, since editing during this stage can prevent you from dedicating unnecessary time and labor to generating content that may be potentially eliminated. They can bring clients closer to final production more quickly, allowing them to pinpoint potential problems related to lighting, cinematography, and sound production. This means fewer iterations during implementation, since the major changes that need to be made have already been detected.

Animatics can range from crude, animated sketches and improvised video footage to polished motion graphics sequences that combine 2D and 3D animation with hand-drawn and digital illustration. When creating an animatic, it is important to keep in mind that you are not just presenting an animated slideshow of the storyboard imagery; rather, you are presenting the types of movements, changes, and camera angles that may occur in the final production.

In an animatic for an in-store video showcasing Nike’s Air Max 2, Terry Green of twenty2product was presented with several live footage assets and asked to develop a scheme that would tie them together and integrate them with text and graphics. He quickly composited stock images and the video footage to provide a clear idea of how the final piece would be animated and sequenced. This allowed both twenty2product and the client to assess potential problems, develop solutions that would remedy those problems, and rethink the entire approach at an early stage prior to production (9.24).

9.24 Frames from an animatic for Nike’s Air Max 2 in-store video. Courtesy of twenty2product.

9.25 These anirnatics were used in a pitch for the worldwide in-store presentations of the German fashion brands ESCADA and ESCADA Sport. Courtesy of Daniel Jenett.

9.26 Frames from the final in-store presentation for ESCADA. Courtesy of Daniel Jenett.

Summary

Assessment, the first step in conceptualization, begins with defining an objective before plunging into the creative waters. This objective must consider the demographics of the target audience and their prior knowledge of the subject being communicated. Research is key to being well informed about your topic, and thorough analysis of the subject must be conducted before conceptualization takes place. Motion graphic designers must also understand budgetary constraints, deadlines, and the degree of client flexibility to new ideas. These restrictions should not be perceived as limitations to creativity, but rather, as creative guidelines that can help give ideas direction. Direct communication with the client can avoid frustrations down the road. Clients can be convinced on an idea, provided that a relationship consisting of mutual trust and respect has been established.

Designers should be aware of obstacles that impede creative thinking and obscure artistic judgment, such as overused trends, effects that lack ingenuity, and the over-abundance of stock images and fonts. They should also embrace pathways to creative thinking. Inspiration can be achieved by establishing personal connections with the subject, conducting adequate research, and involving the client. Risk taking and experimentation can also be liberating by preventing reliance on safe, mainstream design solutions.

Once ideas have been formulated, they must be cultivated through evaluation, selection, clarification, and refinement.

A storyboard is a cohesive succession of frames that establishes the basic narrative structure of a concept. It shows how events will unfold over time and identifies key transitions between events. The single most important measure of a storyboard is its continuity. Pictorial continuity indicates a cohesion in the content and style of visuals. Sequential continuity communicates a comprehensible flow of events between frames. A storyboard usually goes through several revisions before it is refined and presented as a final comprehensive.

Animatics, or animated storyboards, help resolve motion issues ahead of time. They can be time and cost effective, as they can allow clients to pinpoint potential problems early. Animatics can range from crude, animated sketches to polished motion graphics sequences that combine 2D and 3D animation with hand-drawn and digital illustration.