Managing What Has Gone Wrong (or Right!): Issues

An issue is something that has happened and either threatens or enhances the success of the project. Compare this to a risk or opportunity, which are things that might happen.

‘There are no hopeless situations: there are only men who have grown hopeless about them.’

CLARE BOOTH LUCE

- Be open about issues within your team – declare them.

- Never ‘sit’ on an issue – escalate it if you can’t deal with it.

- Use the team to resolve the tricky issues.

What do we mean by ‘issues’?

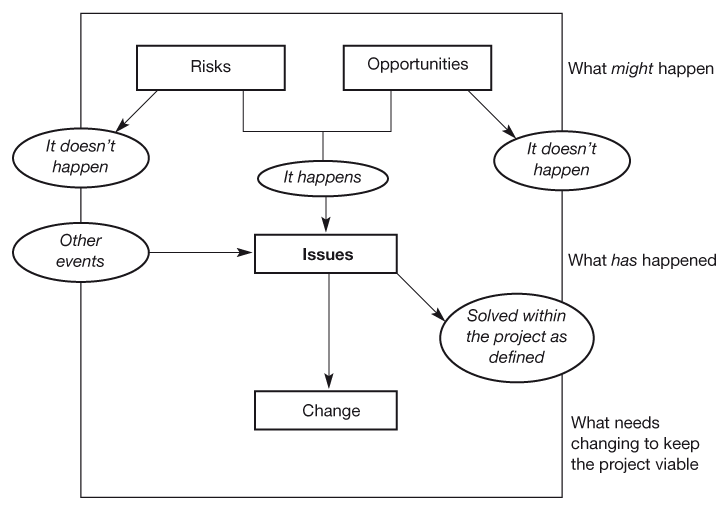

Issues management is the process for recording and handling any event or problem which either threatens the success of a project or represents an opportunity to be exploited. Figure 24.1 shows the context: an issue occurs either as a result of an identified risk or opportunity event occurring or as a result of some unexpected event. An issue can either be dealt with within the project, as defined, or will require a change in order to keep the project viable. Examples of issues are:

Problem issues:

- the late delivery of a critical deliverable;

- a reported lack of confidence by users;

- a lack of resources to carry out the work;

- the late approval of a critical document or deliverable;

- a reported deviation of a deliverable from its specification;

- a request for additional functionality;

- a recognised omission from the project scope.

Opportunity issues:

- a contract negotiation is concluded early;

- a breakthrough on a new technology cuts months off the development time;

- a new, cheaper source of raw materials is located;

- the enrolment of key stakeholders happens sooner than planned;

- a contract tender comes in significantly less than the pre-tender estimate.

An issue is something that has happened and either threatens or enhances the success of the project. Compare this to a risk or opportunity, which are things that might happen.

When talking to people be careful, as ‘issue’ can also mean a ‘topic’ or an ‘important point’: unless you are both tuned to the same definition you may find your conversations confusing!

Figure 24.1 Risks, opportunity, issues and change

An issue occurs either as a result of an identified risk or opportunity event occurring, or as a result of some other unexpected event. An issue can either be dealt with within the project, as defined, or will require a change in order to keep the project viable.

When an issue is identified

When an issue is identified, you should:

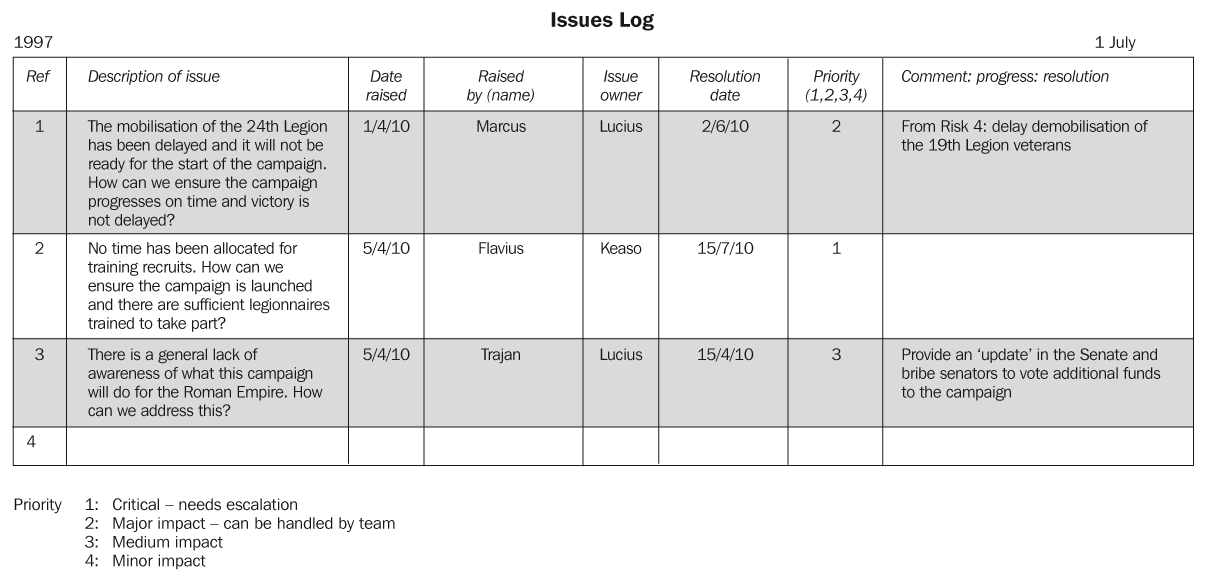

- Record in the issues log any issue which has been drawn to your attention for resolution. (An example issues log is shown in Figure 24.2.) You should:

- describe the issue;

- record who brought it up and when (date);

- rate the issue priority (1 (critical) to 4 (minor impact)).

- Decide and agree who will be accountable for managing the issue’s resolution. If the issue cannot be dealt with by the project team you should refer outside the team to a person who has the necessary level of knowledge and/or authority to deal with it (to the project sponsor or project board for example). You should record, in the log:

- the name of the person accountable for managing the resolution of the issue;

- the date by which resolution of the issue is expected.

- Regularly update the progress commentary on the log.

- Once the issue has been resolved, record the method and date of resolution in the log. The line can then be shaded to show that the issue no longer requires attention. If the issue resolution requires an amendment to the project scope (deliverables), cost, timescales or benefits, it should be handled through the change control process (Chapter 25).

- Report new, significant issues in the regular project progress report (see Chapter 19).

You should expect a large number of issues to be raised at the start of the project or at the start of a new stage within the project. These will mainly be from people seeking clarification that aspects of the project they are concerned with have been covered. This is a rich source of feedback on stakeholder concerns as well as a check on completeness of the project plan.

Make sure you record issues, even if you have no time to address them or cannot yet find a person to manage the resolution. Just making them visible is sometimes enough to start resolving them (see case study). Many issues cannot be resolved on their own simply because they do not reach the core problem; they are merely symptoms. Once other ‘symptoms’ appear as issues it is possible to start making connections which can help identify the core problem. Once this is solved a number of issues can be struck off in one go.

Figure 24.2 Typical issues log

The issues log contains the list of all the ‘happenings’ which either threaten the success of the project or which may lead to an opportunity. It comprises a description of the issue, the date it was raised, who it was raised by, the name of the person accountable for resolving it and a target date for resolution. The final column contains notes to help the reader understand the current situation or record how the issue was resolved.

A project manager was heard to say to another, after running an issues log for some months:

‘This is my magic list. All I do is list the problems on it, share them with my team and … magic! They get resolved!’

‘I don’t believe you; it looks like a load of bureaucratic nonsense to me.’

‘Honestly. I have to work on some of the key ones quite hard myself, but many others are sorted out by the team without me. They see them written there and just act on them if they can. It’s all a matter of creating your own luck.’

The power of the issues log is related to its accessibility. If it is kept secret, no one will know what the problems are and hence will not be able to help. This openness does, however, carry its own risks. If seen by an uninformed stakeholder, an issues log can look like a negative and damning document for the project. You should, therefore, be very careful how you write up the issues and how you circulate or communicate them. Avoid being personal and concentrate on problems: the old saying ‘be tough on the problem, not on the people’ is very pertinent here.

‘I know that’s a secret for it’s whispered everywhere.’

WILLIAM CONGREVE, 1670–1729

Tips on using the issues log

- Phrase the issue as a question; this is more powerful in helping to focus on a solution.

- Have only one issue per ‘line’. Grouping a number of issues together (even if related) makes identification of a solution difficult.

- Do not add to existing issues or they will never be resolved; record a new issue if a different facet becomes apparent.

- Make cross-references between issues or refer back to the risk or opportunity logs (by a note in the ‘comment’ column) if this is helpful.

- Keep all issues visible, even those which have been resolved, as this shows achievement in overcoming problems and exploiting opportunities. It also acts as a check in case the same issue resurfaces later. Shading completed issues makes it clear which are live and which are resolved.

- If the resolution of the issue requires a project ‘change’, put a cross reference to the change log in the resolution column.

- Be open with your issues log; share it with the project team and others on whom the project will have an impact.

A manufacturing organisation was relocating its works. It was intended that the existing plant would be moved and operated in the new location. After the site was acquired and construction was almost completed an issue was raised under European legislation that the old plant would not be allowed to run in the new location. It was deemed to be a new site and hence all plant had to conform to new emission restrictions immediately.

An issue was logged and immediately escalated to the project sponsor as the project manager had no knowledge or power to deal with this. The project sponsor quickly circulated the problem among various contacts within the organisation. Very soon a specialist unit was identified in the head office that was able to review the issue. It found that the issue was a misinterpretation of the legislation and was not valid. The issue was potentially a show stopper for the project. By identifying it and describing it accurately, however, the issue was able to be circulated and resolved (or in this case dissolved). A potentially very expensive change to the project was thus avoided.

POINT OF INTEREST

Remember, an issue can be raised at any time by anyone and is the means of making a problem visible and having it escalated to the level where it can be resolved.

24.1 RESOLVING ISSUES – FROM BREAKDOWN TO BREAKTHROUGH

The following process, if used in full, is a very effective and powerful driver for resolving issues. Followed rigorously it will enable you to ‘breakthrough’ an issue which is blocking your project or programme. The toughest part is to declare that you do in fact have a problem. Doing this puts you in a position of responsibility which will enable you to proceed. Be careful, however; the natural tendency will be for you to dwell on what’s wrong: what’s wrong with you, or with the project, or with ‘them’. Steps 3 to 8 should be done with those who have a stake in the issue in a facilitated, workshop setting, recording the input from the group on flip charts. Do all the steps and do them in the right order. Do not jump ahead.

- Declare that you have an issue!

Tell everyone who could possibly have an impact on resolving the issue, particularly those you do not want to know about it. Don’t hide the issue. Merely putting it on your issues log is not enough. Actively tell people! - Stop the action

Call everything around the issue to a halt. Don’t react. Don’t try to fix it. Relax. - What, precisely is the issue?

Exactly what did or didn’t happen? When? Distinguish between facts and rumours. Then describe the issue in one sentence. This is the sentence you should write in the issues log. - What commitments are being thwarted?

Which of your commitments is being thwarted, stopped or hindered by the issue? Remind yourself of the reasons for the project in the first place and the drivers for action. - What would a breakthrough make possible?

What would the resolution of the issue, under these circumstances, look like? What would it make possible? Are you really committed to resolving this and furthering these possibilities? If so, continue. - What’s missing? What’s present and in the way?

Take stock of the entire project. What’s the situation now (stick to facts!)? What’s missing, which, if present, would allow the action to move forward quickly and effectively? What’s present and standing in the way of progress? - What possible actions could you take to further your commitments?

Leave the facts of the current situation and what is missing in the background. Stand in the future, a breakthrough having been accomplished, and create an array of possible actions. Look outside your paradigm. Think laterally. - What actions will you take?

Next, narrow down the possibilities to those with the greatest opportunity and leverage. Not necessarily the safest and most predictable! Then choose a direction and get back into action. Make requests of people and agree the actions needed. Hold them to account on those actions.

(Adapted, with kind permission of the London Peret Roche Group, from their ‘Breakdown to Breakthrough’ technology. Copyright © 1992, N J.)