Managing the Finances

Recording actual costs and committed costs

Just as a schedule plan is used as the baseline for measuring progress in terms of ‘time’, the financial plan is the basis for measuring costs and financial benefits.

‘We haven’t the money, so we’ve got to think.’

LORD RUTHERFORD, 1871–1937

- Plan in summary for the full project.

- Base your costs on the same work breakdown as your schedule.

- Estimate in detail before you start work on the next stage.

- Once a budget is agreed, baseline it.

- Keep your eye on the future – forecast benefits and costs regularly.

The financial plan

After managing time, management of the finances is the next most important and fundamental aspect of project management. Without a good schedule plan it is impossible to have a reliable financial plan. However, while the schedule is the aspect of a project most visible to outsiders, cost is often the most visible to insiders, such as the management team – sometimes it is the only aspect they see (or want to see!).

At a simple level, a financial plan will tell you:

- what each stage and work package in the project costs;

- who is accountable for those costs;

- the financial benefits deriving from the project;

- who is accountable for the realisation of those benefits;

- financial commitments made;

- cash flow;

- financial authorisation given.

In addition, some organisations also derive the net effect of the project on their balance sheet and profit and loss account.

Just as the schedule plan is used as the baseline for measuring progress in terms of ‘time’, the financial plan is the basis for measuring costs and financial benefits. Many of the other principles I have already explained on schedule management are also applicable to the management of finances. Schedule and cost plans should share the same work breakdown structure (WBS) (see p. 141). By doing this you ensure that:

- accountability for both the schedule and cost resides with the same person;

- there is no overlap, hence double counting of costs;

- there is no ‘gap’, i.e. missing costs.

In practice, you will develop the financial plan to a lesser level of work breakdown than you would the schedule plan.

The financial plan, like the schedule plan, is developed in summary for the full project and in detail for the next stage. There is little point in developing an ‘accurate’ and detailed financial plan on the back of an unstable schedule plan. No matter to what level of granularity you take the calculations, they will be fundamentally inaccurate. You should take the level of accuracy and confidence forward with the schedule and related costs matching.

The costs are influenced by the following, which you must take into account when drawing up your plan:

- the scope of the project;

- the approach you take to the project;

- the timescale to complete the project;

- the risks associated with the project.

Financial management controls

Financial management of a project comprises:

- estimating the costs and benefits (preparing the financial plan);

- obtaining authorisation to spend funds;

- recording actual costs, committed costs;

- forecasting future costs and cash flow;

- reporting.

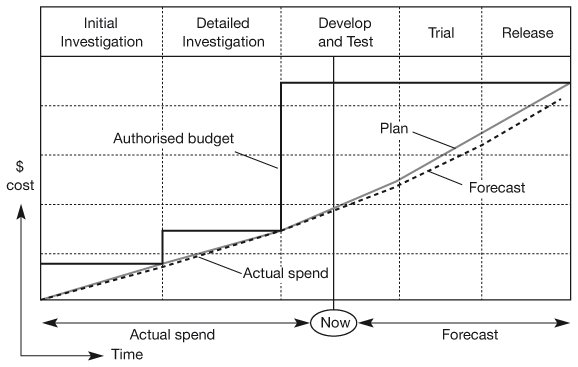

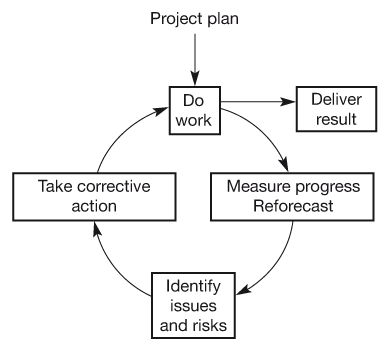

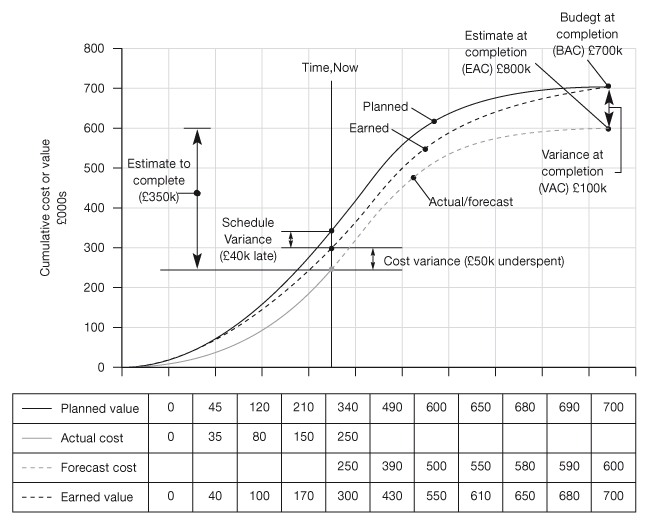

This is illustrated in Figure 22.1 and done in the context of the project control cycle. Tracking progress toward your objective is essential. If you don’t do it you simply won’t know how much the project will cost. The control cycle is exactly the same as that used for schedule management and is shown in Figure 22.2: once a financial plan has been agreed, it is necessary to measure progress against the plan, reforecast to the end, note any variances and take steps to bring the project back within budget if need be.

Figure 22.1 Project costs

This figure shows cumulative spend for a typical project, which includes the sum actually spent plus the forecast to completion. This can be compared against the plan (or budget). In the example, the project is forecast to be completed slightly below budget. Also shown is the authorised budget. This goes up in steps. At first a small amount of funding is given to undertake the initial investigation only. This is then increased, based on the results of the initial investigation, to cover the cost of the detailed investigation. Finally, a full business case provides the basis to authorise the remaining funds to complete the Development and Test, Trial and Release Stages.

Figure 22.2 Project control cycle

The project control cycle comprises doing the work as set out in your plan, identifying any risks, opportunities or issues and taking corrective action to keep the project on track. From time to time, results, in the form of deliverables, are generated. (Copyright © PA Consulting Group, London.)

BOOKKEEPING!

You should distinguish between the management of costs from a management accounting perspective and from a financial perspective The latter relates to ‘bookkeeping’ and where the transactions appear in the formal accounts. In the management of projects, this is of little or no use. Managing the actual spend and cash flow provides far greater control.

Estimating the costs

’A little inaccuracy sometimes saves tons of explanation.’

SAKI

Your cost estimates should be based on the work scope and schedule plan defined in the project definition. You should use the same work breakdown structure as the schedule plan and estimate to the same level of accuracy (summary versus detail).

Your estimate should be made up of:

- the cost of using your own employees;

- the cost of external purchases made as a result of the project.

The overall cost plan should be built up from three elements:

- the base estimate;

- scope reserve;

- contingency.

The base estimate is the total of costs for all the activities you have identified, including the cost of your own employees’ time and all external purchases.

The scope reserve is an estimate of what else your experience and common sense tells you needs to be done, but has not yet been explicitly identified. This can be very large: for example, the scope reserve required in software projects can be as high as 50 per cent of the base estimate.

The authority to use ‘scope reserve’ is normally delegated to the project manager who should use formal change control to move funds from ‘scope reserve’ to ‘base estimate’.

Contingency is included in the estimate to take account of the unexpected, i.e. risks. It is not there to compensate for poor estimating. If a risk does not occur, the money put aside as contingency should not be spent. For this reason, the authorisation for spending contingency rests with the project sponsor. Again, formal change control should be used to move the costs from ‘contingency’ to ‘base estimate’.

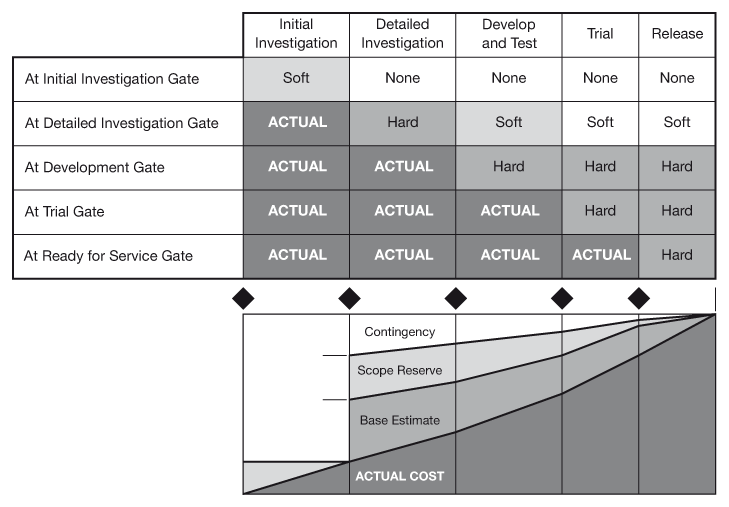

The proportion of your estimate divided between these elements will alter as the project moves through its life cycle stages. You should expect a higher proportion of scope reserve and contingency in the early stages than in the later stages. The accuracy of estimates also alters depending on the life cycle stage of the project. Figure 22.3 shows that in the earlier stages you expect the bulk of the cost to be ‘soft’ except for the next stage. The next stage should be a ‘hard’ estimate. This matches the principle of summary and detail planning. Summary plans tend to be soft, detail plans hard.

A soft estimate is one to which only a low level of confidence can be placed.

A hard estimate is one in which you have high confidence.

Regardless of whether your estimates are soft or hard it is important that you state any assumptions, constraints, or qualifications you have. These should be recorded in Part 1 of your business case (see p. 294).

Authorisation to spend funds

All organisations have rules which prescribe who has the authority to spend money. If you are a subsidiary, such rules may be imposed on you by your parent organisation. Such processes can be onerous and time consuming if not matched to the project process you are using. As a minimum you should ensure that the timing of financial authorisation, as laid out in your finance processes, matches the gates in your project framework.

Each of the gates in the project framework offers the opportunity to allocate funds to the project. You should allocate a limited amount of money at the very start of the project (Initial Investigation Gate) to investigate the proposal so that an informed decision on whether to proceed can be made later at the Detailed Investigation Gate. Subsequently, further funds can be allocated on a stage-by-stage basis until the project is completed.

Alternatively, it may be more convenient to allocate funds for more than one stage, thus avoiding the need to obtain authorisation a number of times and saving time on your projects. If this is done it is still part of the project sponsor’s and project manager’s accountabilities to undertake the gate reviews to check on the on-going viability of the project. Just because you’ve been given the money, it doesn’t mean that you continue blindly.

For long stages it may be prudent to hold back full authorisation and introduce intermediate review points, when the project is reassessed prior to further funding being authorised. Such points may conveniently be prior to major commitments, such as letting a contract.

The project framework will work for whichever way you choose to arrange fund authorisation. The key is to ensure that such authorisation processes:

- are consistent with the principles of the project framework;

- concentrate only on substantive issues;

- are not too lengthy;

- do not duplicate other reviews or approvals.

The decision-making approach outlined in Chapter 3 (p. 57) poses three questions:

- Is the project on its own viable?

- What is its priority relative to other projects?

- Is funding available?

The control document (Business Case) used at the Detailed Investigation Gate and at the Development Gate is the same one for each question – you do not need to provide a different document for each question. This has two advantages:

- You do not need to write a number of different but similar documents.

- You can be sure that the answer to each question is based on compatible (the same!) information.

In certain circumstances you will be able to delegate all the decisions to the same person or group. This all depends on how you are organised. However, distinguishing between the key questions being addressed will help you concentrate on making the decision. For example, there is no point in prioritising a project (question 2) which cannot stand up in its own right (question 1).

Throughout this book I have distinguished between the terms approval and authorisation. Approval is used when an individual accepts a deliverable as fit for purpose such that the project can continue. Authorisation is used for allocating the funding and resources needed to carry on the project and giving the project sponsor and project manager the authority to direct and manage the project.

Approval in some form is always required before any funding is authorised. However, the converse is not true; just because authorisation of funding has been given, it does not mean that approval has been given to complete the project. For example, you may have been given, at the Detailed Investigation Gate, full funding to complete a simple project. Work during any of the subsequent stages may uncover issues which cannot be resolved. In which case approval at subsequent gates may not be forthcoming and the project should be terminated. In such circumstances the unused project funds should be returned to their source.

Authorisation of funds is usually based on some form of investment appraisal. I do not intend to go into this in any detail. There are many books which deal with the plethora of methods which can be used. While each organisation will have its preferred approach, the following key points should be considered:

- Investment appraisal should be based on cash flow.

- Discounted cash flow techniques are the most favoured.

- Use least cost development (lowest net present value, NPV) if you must do the project.

- Use internal rate of return for other projects.

- Concentrate on substantive elements only. If a figure is wrong and has no significant impact on the appraisal, don’t waste time changing it.

- Use sensitivity analyses liberally – they give you more feel for the project than spurious accuracy in estimates.

- Use scenario analysis to check possible outcomes.

And finally:

- Do not consider financial criteria as sacrosanct. Many projects are worth doing for non-financial reasons because they support your basic strategic direction.

- Some things can’t be reduced to financial terms. Just because you can’t count them doesn’t mean they don’t count!

Recording actual costs and committed costs

If you are to have any visibility over the cost of your project, you will need to have a system of capturing the costs, from wherever they originate in your organisation and allocating them to the project. Similarly, you will need to have a method of capturing commitments relating to each project (see also p. 265). (Commitments are orders placed and hence the money, although not yet spent, is committed as part of an agreed contract.) If this is to have any meaning costs should be split into:

- money that stays within the organisation (e.g. cost of labour, drawing on internal stores);

- money that leaves the organisation (e.g. paid to contractors, consultants, suppliers).

In cash flow terms this distinction is critical as the former have already been ‘bought’, but you have not yet decided what project or activity to apply them to. The latter are not spent at all if the project does not proceed.

In addition, it is essential to have the costs captured for each stage of the project so that you can confidently manage actual spend against authorised budget on a stage-by-stage basis. Most mature organisations also capture costs at a lower level in the work breakdown structure than that.

WHAT IF I CANNOT MEASURE COSTS AS YOU SUGGEST?

Having a good project or matrix accounting system is vital if you are to reap the full benefits from business-driven project management. If you are unable to account for costs on a project-by-project basis you will have to rely on conventional cost centre-based accounting or manual processes to maintain control: you have no alternative. This will mean that the balance of power remains firmly with the functions that own those cost centres and away from the project (see Figure 2.11).

It is still well worth using the tools, techniques and guidance given in this book but you will be limited in the depth to which they can be applied and ingrained in your culture. No matter what you as managers say concerning the importance of projects, line managers will pay more attention to their cost centre accounts simply because they are visible.

In Chapter 2, I pointed out that any process sits within a balance of systems, culture and structure. You will therefore need to adapt how you apply the process to meet your system limitations while you drive towards the flexible culture you seek.

Financial reporting

The future is more important than the past. Any money you have already spent is lost and cannot be recovered. For this reason you must not only log what you have actually spent, but also forecast what is yet to be spent. The important figure to concentrate on is ‘what the project will have cost when it is completed’.

To arrive at this figure you simply add any costs incurred to date to any cost you have yet to incur. The forecast is simply an estimate of what figures are going to appear on your project account during any particular period. So your forecasts must:

- use the same costing methods as actuals are measured;

- be forecast on at least a stage-by-stage basis;

- be timed to match the actuals (usually a monthly cut-off is used).

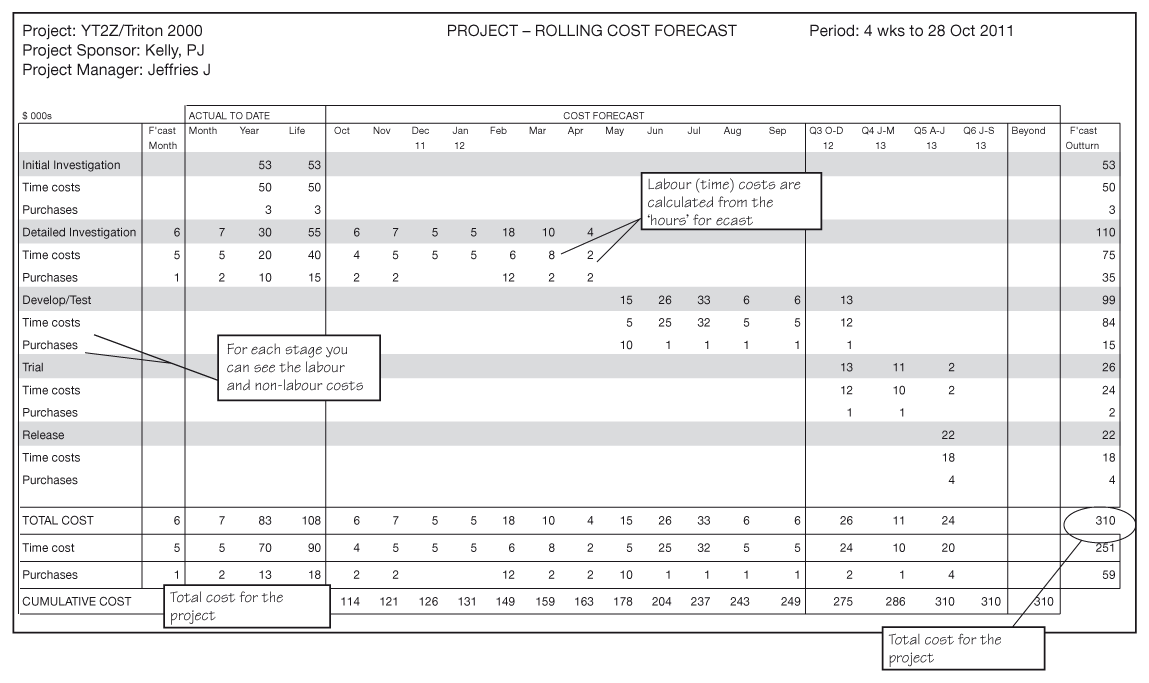

Figure 22.4 shows a typical report for building up the forecast.

Organisations, by means of their accounting and operational systems, collect a considerable volume of data. Unless these data are converted into meaningful information, they are useless. Any reports you produce must be aimed at providing useful information which will act as a prompt for action. This implies the reports should be targeted at specific roles within your organisation. As the reports seek to promote action they should be:

- timely;

- as accurate as possible within those time constraints;

- forward looking.

Further, unless individuals involved in collecting the data gain some benefits themselves from them, the quality of the data will erode and the reporting will become useless.

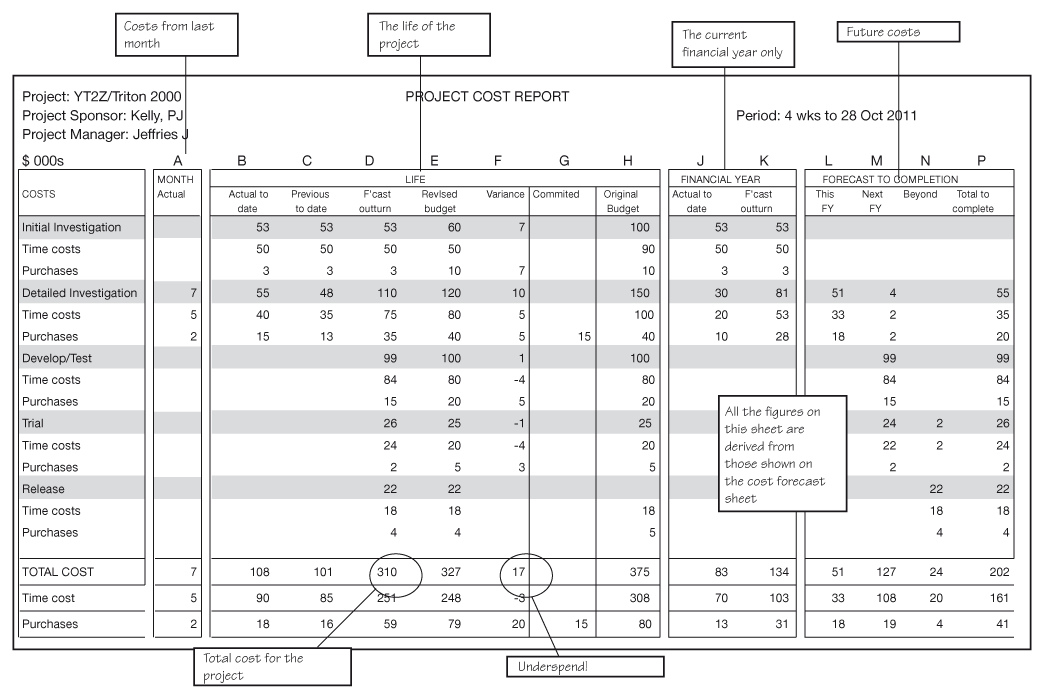

Figure 22.5 is a typical financial report and tells you, in financial terms:

- what has been spent to date;

- the expected outcome for the project;

- the impact on the current financial year;

- the cost of work yet to be done.

In addition, you should have detailed reports which:

- list every transaction/purchase made on the project;

- detail time booked to the project.

Figure 22.4 A typical report for building the forecast

This report gives a stage-by-stage summary of the total costs for a project and is ideally suited for building the forecast. For example, the time cost line could be derived from a manpower forecast such as that given in Figure 16.2.

Figure 22.5 The financial report

A report such as this gives you, on a stage-by-stage basis, all the key financial information you should require: actual costs, forecast costs, commitments for the project as a whole and by financial year; it is derived directly from the data in Figure 22.3.

Earned value

Integrating cost and time reporting

One of the difficulties with measuring project costs against planned costs is that, on its own, you can gain very little information from a fact such as: ‘At this point in the project we planned to have spent £340,000 but have only spent £250,000.’ What does this apparent £90,000 underspend mean?

- Have we underspent and the project is going very well?

- Are we running late, but spending at the correct rate?

- Are we overspending and running late?

From the basic facts I have given you, you cannot tell. Earned value analysis (now called earned value management) was created by the US Department of Defense in the 1960s to help solve this problem and bring greater clarity to measuring the performance of their contractors. The use of this approach is often mandated by government agencies and some multinational organisations when letting contracts and it is in this context you are most likely to find it. It is less apparent in other situations and rarely (if at all) seen practised on an enterprise-wide basis.

The Project Management Institute’s glossary defines earned value management (EVM) as: ‘A method for integrating scope, schedule and resources and for measuring project performance. It compares the amount of work which was planned with what was actually earned with what was actually spent to determine if cost and schedule performance are as planned.’

I doubt there are many people who can understand that in one reading! Perhaps this inherent complexity is what makes its use so rare except in mandated circumstances and what has led the PMI to replace a plethora of abbreviations (such as BCWS, BCWP, ACWP) with simpler equivalents.

The S-curves

For many organisations, the simple two-line ‘S-curve’ (‘planned cost’ and ‘actual cost + forecast’) shown in Figure 22.1, supplemented by milestone tracking, is sufficient for project tracking purposes. Nevertheless, as more organisations automate their project management environments it is possible that earned value techniques could become more common. Whilst Figure 22.1 uses only two lines for cost tracking, EVM adds a third line, which shows the earned value of work completed to date. The earned value line is costed using the same basis as used in the plan. Thus if work package A is planned to cost $25,000, once it is completed, the earned value is $25,000 regardless of how much it actually cost. It’s rather like standard pricing. It follows that if a project produces all its deliverables at the point in time they were planned to be delivered, the earned value and planned lines would be coincident. Figure 22.6 shows this in the form of S-curves.

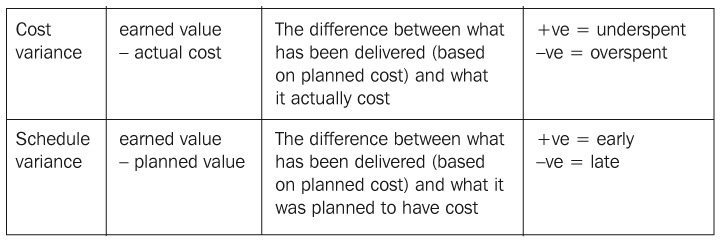

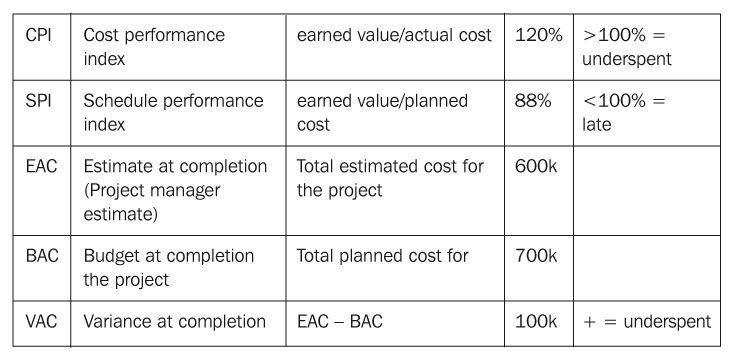

You can calculate two specific variances from these three lines:

Figure 22.6 Earned value management – typical project

The three lines used in the method are shown – Planned, Earned and Actual – each of which shows the typical S-curve shape. If the project ran exactly as planned, these lines would be coincident.

Looking at Figure 22.6, we can now see the answer to the question I posed at the start of this section. Progress on the project is mixed: it is underspent but running late. So far, what has been completed has been delivered £50,000 cheaper than planned (cost variance = +50) but £40,000 less work has been completed than should have been (schedule variance = – 40). On the other hand, the project is forecast to be completed £100,000 under plan and almost one period early. You may wonder what is behind such an optimistic forecast; perhaps all the difficult work has been done up-front, thereby forming a better basis for undertaking the remainder of the project.

Performance indices

Estimating the cost of the project at completion is where one of the more controversial calculations for the method comes in. A factor called the cost performance index (CPI) is widely used to forecast total cost of the project at completion. If a work package within a project is in progress and is over-budget, the calculation assumes that the final cost will exceed the planned cost by the same margin. This assumption implies that things will neither improve nor deteriorate further. In our example, the method would indicate a cost at completion of £583,000, somewhat less than the £600,000 forecast by the project manager.

Experts in the use of this method will spot the problem immediately. In the example, the project has been treated as a single entity, whereas proper use of the method requires the project to be divided into a large number of work packages, with the earned value analysis performed discretely on each. They are then summed to provide the overall status for the project.

How useful is the method?

The usefulness of earned value management as a method is controversial. The greatest critics see it as a waste of time, whilst there are enthusiastic advocates claiming it is ‘the only way’. In the middle are people who see that the information gained is potentially useful but are sceptical as to whether the effort needed to collate the data is worth it. As stated earlier, the method was primarily designed for the contracting environment and as such is more applicable to the post-investigative stages (Develop and Test, Trial, Release). The uncertainty around the investigative stages makes it very difficult for the method to add any additional information for the data collection and analysis effort required.

Its usefulness is dependent on having:

- a detailed plan, with appropriate WBS;

- accurate cost information;

- realistic progress reporting;

- project managers skilled in the method.

If any one of these is deficient, the benefit of the results will be significantly devalued. For enterprise-wide project management, it is not likely to prove useful simply because of the wide range of project management competencies such an environment encompasses. Simplicity and ease of data collation is the key if the method is to gain a strong foothold outside its traditional ‘large contract’ environment. In such cases, however, the results can provide management with an early indication as to the performance of a project, provoking action to resolve problems sooner rather than later.

22.1 PROJECT FINANCES

| 1 | Take the list of projects that your business is currently undertaking or, alternatively, the output from Project Workout 3.2. | ||

| 2 | Choose any five projects which are in the Develop and Test Stage or beyond. | ||

| 3 | Ask each of the following people questions (a) to (e): | ||

| • | the finance manager; | ||

| • | project sponsor; | ||

| • | project manager. | ||

| (a) | For both time costs and purchases, provide, for the project as a whole, as at the close of the last month’s accounting period: | ||

| • | costs spent to date; | ||

| • | costs spent this financial year; | ||

| • | estimated cost at completion; | ||

| • | agreed budget, when the project was authorised. | ||

| (b) | Answer question (a) for the current work stage. | ||

| (c) | How are ‘time costs’ calculated? | ||

| (d) | Where were these data obtained from? | ||

| (e) | State how easy or how difficult the information was to obtain. | ||

| 4 | Consider the replies. How long did it take for them to be compiled? Do they give the same information? What parts are missing? Were the same sources for the data used? If there is great consistency, fine. If not, look behind the replies. For example, if it takes a long while to compile the information or some is missing, can you reasonably expect your project managers to work within their budgets? Is it acceptable to make them ‘fly blind’ without adequate instruments? | ||

WHEN VALUE DOESN’T MEAN VALUE!

The term ‘value’ has much wider uses than that described in this section. You therefore need to be clear what this method doesn’t give you. Earned value does not tell you:

- the residual ‘value’ of the project at a point in time if it were to be terminated;

- the benefit gained from the project to date;

- the value of any assets produced by the project.

Nor does it have anything to do with another discipline – value management – which is aimed at choosing the most effective way to meet a particular business need. This is a technique which is primarily used during the investigative stages of a project.