Managing Benefits

In short, benefits are about making more money, about using existing resources and assets more efficiently, and about staying in business.

‘What is a man profited, if he shall gain the whole world and lose his own soul?’

MATTHEW 16:26

- Always measure benefits against a known baseline.

- Make benefits tangible, where ever possible.

- Place benefits in the wider business context.

- Look out for unwanted side effects from your project.

Benefits and drivers

Legitimate projects

Realising benefits is the sole reason for undertaking a project. If there are no benefits, there should be no project. It is for this reason that the role of project sponsor is vital. He or she is the person in the organisation who requires the benefits to fill a particular need, in pursuit of a stated business objective.

To be ‘legitimate,’ a project must satisfy at least one of the following conditions:

- maintain or increase profitable revenue to the business, now or in the future;

- maintain or reduce the operating costs of the business, now or in the future;

- maintain or reduce the amount of money tied up within the business, now or in the future;

- support or provide a solution to a necessary or externally imposed constraint (e.g. a legal or regulatory requirement).

In short, benefits are about making more money, about using existing resources and assets more efficiently and about staying in business. Drivers are frequently defined by words such as ‘growth’, ‘efficiency’, ‘protection’ or ‘demand’, which reflect an organisation’s focus at any point in time.

The first three conditions relate to the net cash flow into the organisation. Money is the organisation’s key measure of commercial performance in the private sector and value for money in the public sector. It includes measurement of revenue, investments and the costs of running the organisation.

The fourth condition is often referred to as a ‘must do’ project. It is nevertheless essential that such projects are fully costed in order to determine the least cost, highest value approach to fulfilling the need. This cost can then be placed in the context of the organisation as a whole in order to determine whether the organisation, or the impacted part of the organisation, can afford the change and remain viable.

Value drivers – what they are and why they are useful

If you have worked in mergers and acquisitions you may be familiar with how due diligence is carried out to assess the value and the liabilities of the target company. Acquiring companies look at those things about the target company that drive its costs, its revenues and its asset value. The approach, however, is also useful when driving out greater efficiency and effectiveness in your own organisation. The objective is to identify the set of value drivers that are specific to the organisation, which can be checked off against the organisation’s chart of accounts (if it is simple enough – one organisation I know of has more than 11,000 account headings!). Example value drivers are:

- Reduced personnel costs

- Reduced head count

- Reduced/avoided recruitment

- Reduced employment overheads

- Reduced cost of ownership of assets

- Reduced maintenance costs

- Reduced security costs (inc. losses)

- Reduced cost of rectification

- Reduced effort per error on investigation and recovery

- Reduced volume of re-supply per error

- Profitable acquisition

- Profitable acquisition of valuable estate

- Profitable acquisition of valuable IT systems

- Profitable acquisition of valuable production assets/plant

- Improved profitable sales infrastructure

- Enhancement of profitable new sales personnel skills and relationships

- Acquisition of profitable improvements to sales processes

- Acquisition of new company data and knowledge that are put to profitable use in sales

If you know what drives your organisation’s costs down and what drives its revenues and asset values up, you can compare these against the business changes your project is enabling and start to see exactly how your project is driving benefits realisation. This technique is the part of Isochron’s Dimension Four® method (see p. 330), which enables a project sponsor to identify extended benefits, just as projects normally identify their extended costs. These benefits usually go far beyond those that people think of when they are working within imposed, budget-cutting targets. Dimension Four® recognises six categories of benefits, which expand the four ‘legitimate projects’ mentioned earlier:

- bottom-line savings in the cost of what we are spending now, in this Profit-and-Loss year;

- avoided costs of future committed spend;

- future revenue increases;

- new valuable assets;

- ‘real options’ – assets the project will build which creates options to generate more cash benefits in the future;

- value-for-money – benefits that have no cash value to the organisation but are things that stakeholders want and have been promised.

One of the useful spin-offs of using value drivers is that it often increases the project team’s (and sometimes the business’s!) understanding of where their organisation’s money comes from.

BEWARE OF EFFICIENCY ‘SAVINGS’

When looking for efficiencies, be very careful not to waste time and energy suboptimising aspects of your business. What counts is the throughput of your business, not the individual efficiencies or asset utilisation of the different parts. Partially finished goods are not the aim, finished goods are. The trap people fall into is assuming that by increasing the efficiency of every part of a business, the whole business will become more efficient. This is not the case, as efficiencies are not additive. This can be very simply demonstrated.

Consider a factory with a five-step process, machines A, B, C, D and E, with a required throughput of 100 units / day. In an ideal world each machine would be sized for 100 units/day. But we live in a world of breakdowns and unexpected events. If each machine operated with 90 per cent reliability, the chances of you actually obtaining 100 units / day are only 60 per cent. You therefore need to oversize your machines to protect your throughput and you deal with breakdowns by ensuring that each machine has a stockpile in front of it to protect against a breakdown further up the chain. However, much of the time individual machines won’t break down and if you are aiming for each machine to operate as near as possible to its limit (i.e. peak efficiency) you will find that stockpiles of partially finished goods will swamp the downstream machines. The net effect will be decreased efficiency downstream because it simply cannot cope with the corresponding increase in throughput.

Eli Goldratt likens this to a chain in his Theory of Constraints. A chain’s strength is determined by the weakest link and you cannot strengthen the chain by adding weight to any other link. In fact, you only weaken the chain, as the weak link now has an even greater load to bear.

Business objectives and benefits

Whilst the conditions in the previous sections may make a project ‘legitimate’, they are not, on their own, sufficient to define the business objectives for the project, nor indeed the wide range of benefits which may result. Business objectives need to include not only the financial figures, but also statements on market positioning, service/product mix, target markets, service quality and such like. Organisations which focus purely on ‘making the numbers’ often end up by ‘making the numbers up’. A finance plan is not a business plan; it is a subset of a business plan. You must always ensure the benefits from each project really are moving the organisation toward its business objectives.

Some project sponsors have no trouble envisaging the end state of the business after the transformational changes. Ask them what their objectives are and their eyes will light up and they will talk with certainty and precision about how the organisation will function in the future and what they see happening. Others will also become animated but will talk in terms of the future being ‘exciting’, exhilarating’ or ‘challenging’, with little or no information as to how the future organisation will function. Another group will look blank and talk only about what is not going right and what the risks are. Sometimes they can be very despairing about the present and fearful of the future. Isochron has developed a technique for this ‘doomsday’ eventuality. It is called ‘Transfiguration’ because it enables groups of people to move from a position where everything appears impossible to a position where everything has proved possible and looks perfect. The approach taken is to list all the complaints and grievances in a workshop and then look for outcomes which would negate these. This is done by rephrasing the complaint in a positive way. This is described more fully in Project Workout 20.3.

Tangible and intangible benefits

Benefits can be:

- tangible – those which can be stated in quantitative terms;

- intangible – those which should be described as far as is possible.

Wherever possible, benefits should be tangible and clearly articulated. Tangible benefits may be measured either in financial or non-financial terms. Financial benefits describe the business objectives in terms of:

- revenue;

- contribution;

- profit enhancement;

- savings in operating costs or working capital.

Non-financial benefits describe the value added to a business that is directly attributable to the project but which cannot be described in financial terms. Again, these benefits should be tangible and measurable, such as:

- operational performance measures;

- process performance measures;

- customer satisfactions measures;

- key performance indicators (KPI).

Care should be taken, however, to query why we should spend money addressing any particular measure or indicator; if it doesn’t eventually help you achieve any of the four conditions given at the start of this chapter, you should seriously consider terminating the project. You may argue that increasing service quality could help you to retain customers, or attract new customers, in which case a financial benefit should result; increasing service quality may enable you to remain in business. You should be able to justify any such assumptions even if the calculation of financial effect is somewhat tenuous.

Intangible benefits are frequently the most problematic to deal with. Whilst it is difficult to link tangible benefits back to a project output, the problem is far more difficult when dealing with benefits which are almost impossible to describe and measure numerically. Some people take the view that all benefits should be meaureable and that if a project has none, it should not be undertaken. This is an extreme approach and not one I agree with. Take for instance a project to implement an accounting system. We all know that any but the smallest organisation needs one and that, intuitively, justifying its cost through financial measures alone is ‘missing the point’. I suggest you treat this as a ’must do’ project in the first instance, determine the most efficient and effective way of meeting the need and see, in the context of your overall business plan, whether you can afford this and want to afford it, bearing in mind everything else you are doing or want to do. Portfolio management techniques are extremely useful in this context (see p. 199). Examples of intangible benefits you will often see in business cases are strategic positioning, competitive positioning (proactive and reactive) and the provision of management information.

ISOCHRON

Isochron® is a specialist ‘think tank’ and consulting organisation, which has developed a set of techniques and tools for benefit realisation which are grouped in a methodology called Dimension Four®. Put together, they reduce the uncertainty of the outcome of a project, but the techniques can be used separately to deal with awkward project difficulties. The method doesn’t have to replace other approaches and complements the approaches taken in this book. Parts of it can be used to together with the Managing Successful Programmes (MSP) and Prince2 methodologies, it also endorses and backs up Lean approaches and Goldratt’s Theory of Constraints.

Like this book, Isochron takes a business-centric view of projects, proposing that projects should be done ‘by the business for the business’. It asserts that, short of external or market changes, any alteration in the cash flows of an organisation can only come about by changes in how the organisation operates and that therefore all benefits must be connected to observable changes in how the organisation works. In the private sector it proposes that every change must be connected to a cash benefit, even mandatory and regulatory ones, and it has a means to do this. It calls the observable changes ‘Recognition Events®’ and the start of observable changes in cash flow ‘Value Flashpoints®’.

The name of the methodology – Dimension Four – is a hint that time is regarded as fundamental in the operation of an organisation. The main processes in the method work right to left – from the future back to the present, from the intended benefit to the cause. Uncertainty is transferred from the outcome to the process – the benefits are treated as non-negotiable but the project plan and solutions are seen as agile and highly negotiable.

Needs, benefits, and project deliverables

All too often the needs which initiated a project can become divorced from the outputs a project produces. It is essential for you to be able to maintain the linkage. When push comes to shove and you need to trim the project back due to overspends or budget cuts, having a clear view on this will ensure you trim the right things. Always remember benefits do not come from projects, they come from using the deliverables which the project produces. Key questions are:

- What are the over-riding business objectives for the organisation?

- What are the needs (or opportunity) to be filled if these objectives are to be met?

- What benefits will result through filling these needs?

- What deliverables do you need to realise those benefits?

- In what way will those deliverables help meet the need?

There is a technique called the functional analysis systems technique (FAST) that has been used for a long time in value engineering, but its inherent simplicity also lends itself to rigorously questioning the benefits a project is being set up to achieve, i.e. the business objectives. You start by stating what you are trying to achieve and then, by asking a series of how questions, you deconstruct this into increasingly specific statements which show the impact of doing one thing on the next one in line. The technique helps you ensure that only necessary elements for meeting the objectives are included in the project. The technique is often called ‘How–Why’ charting, and as such can be used not only in creative thinking (working left to right – how) but also to analyse a current situation (working right to left – why). See Project Workout 20.2 for how to use this method.

Difficulties with measurement

The quantitative benefits above can be measured at corporate level; however, they cannot always be measured directly for an individual project. You may need to take alternative approaches as illustrated in the following examples.

Example 1 – using a surrogate measure, it is not always possible to measure profit for products. In such cases, an alternative measure should be chosen which can be measured and which has a known relationship to profit. Revenue and margin may be such measures. You may also use measures such as numbers of customers, churn, percentage utilisation.

Example 2 – measuring at a higher level, it is not always possible to relate an increase in demand for a service directly to a recent enhancement to that service; it might be the result of other dynamics in the market. In such cases, the project should be tied to a higher level programme or business programme, where the benefits can be measured. For example, an enhancement to a service may be bundled with the overall service which is tracked at product level rather than by the individual projects and initiatives which make up the product plan.

Conditions of satisfaction

Despite difficulties with measurement, every project should have a recognisable method for knowing whether it has been a success. Conditions of satisfaction (introduced in Chapter 19) are used to supplement benefits measurements. They are the conditions which, if met, enable you to declare the project a success. They need to be chosen such that they are indicative of realising the benefits and may relate to a reduction in faults, increase in customers, observable change in behaviour and so on, measured or noted at a particular, defined point in time.

CRITICAL SUCCESS FACTORS (CSFs)

In organisations you will see reference to ‘Critical Success Factors’. These are factors that will ensure achievement of the success criteria for the project – they are not the success criteria. The idea is that if you identify and focus on these success factors, you will directly influence success. The logic is theoretically sound but, in my experience, CSFs are seldom described effectively. Often they are mere platitudes and statements of the obvious, e.g. ‘… that IT provide resources’ or ‘Regular written communications to stakeholders are vital.’ There is little point in repeating such generalities in project documents. In practice, they often represent risks (and as such should appear on the risk log) or are used to define what are better defined as ‘dependencies’ (deliverables required from other projects). My advice is not to use them, but if you do, make them very specific to the project. Concentrate instead on the conditions of satisfaction (see text above) and use your other controls to capture the factors.

NET BENEFITS

When talking of benefit always think in terms of net benefits, that is to say, what’s left after you’ve counted the cost.

Isochron’s recognition events and value flashpoints are special types of ‘condition of satisfaction’. Since the value flashpoints each have an estimated monetary value (together with the sources, assumptions and calculations used), they enable finance and business managers to see how much each business change is worth and where its impact can be looked for in the cash flows. The problem of measurement at a higher level resolves itself because both the recognition events and value flashpoints are almost always found to be duplicated across projects – they all belong to one business level and viewpoint, that of the project sponsor. De-duplication often results in simplification and re-scoping of the projects around the project sponsor’s business needs, as opposed to around the chosen solutions. We maintain a direct link from ‘action’ to ‘benefit’.

If you use Isochron’s approach the project sponsor and stakeholders will have defined, from the outset, precisely what their conditions of satisfaction are – the recognition events that will tell them when their expectations have been met. In the same methodology, the completion of the value streams triggered by the value flashpoints will be the conditions of satisfaction for the financial benefit goals enabled by the project. Isochron solves the ‘measurement problem’ in their methodology by using three spreadsheets:

- One lists the business change outcomes that the sponsor will recognise – the ‘Recognition Events®’.

- The next lists the specific changes to cash flows that the recognition events will cause – the ‘Value Flashpoints®’.

- The third connects the recognition events to the value flashpoints, to show indicatively how much the achievement of each change in the business will contribute to each value flashpoint.

Forecasting benefits

An initial estimate of the benefits and costs must be prepared during the Initial Investigation Stage. During the Detailed Investigation Stage the estimates must be turned into firm forecasts and be agreed by the project sponsor.

Forecasts serve two purposes:

- first, they enable evaluation of the project;

- second, they provide information against which the post launch performance of the project can be measured.

There are four guiding principles for forecasting revenues and benefits:

- Forecasts must be realistic.

- Benefits must be matched by the costs of achieving the benefits.

- Benefits (prices, sales volume, etc.) and costs must be based on the same assumptions.

- Costs and benefits must be forecast for the worst, best and most likely outcome (scenarios).

Profit (or contribution) forecasting needs to take account of three factors:

- Volume/demand.

- Pricing.

- Costs.

The overall financial contribution to an organisation is the product of demand and price less costs. This is the basis for justifying any number of projects whether they are for a new product, a campaign or for increasing efficiency. It is important to keep the total picture in mind to make sure that projects are not created which merely suboptimise a part of the business, creating little overall benefit. For example, there is little point in installing a highly efficient new platform for a service for which demand is decreasing and the volumes required to achieve the efficiency will never be realised.

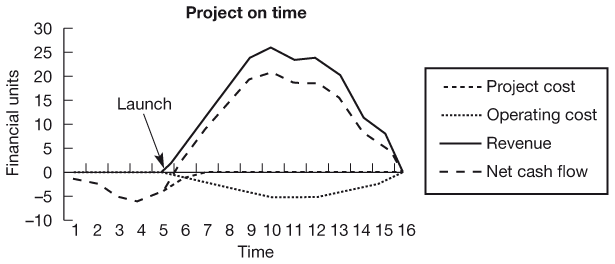

Timing of benefits

When looking at benefits always consider the timing. The earlier you can obtain benefits, the better it is for your business and the quicker you will recover your investment. Discounted cash flow calculations are designed to ensure that the time value of money is taken into consideration when comparing different projects and when deciding whether to invest. This is also why you need to look for opportunities to design your projects to ensure early benefits delivery.

Just as early benefits are a good thing, so delayed benefits are bad. The cost of delays can far outweigh any investment costs and turn a viable project into a financial embarrassment.

Figure 20.1 shows the cash flow for a project over a four-year period. The organisation is looking for a 30 per cent return on investment and this meets it adequately. If this project were to slip two quarters, the benefits would also slip, reducing the present value of the project by about 30 per cent. It would actually be worth overspending by 50 per cent in order to prevent this delay in benefits and regain some of the potential loss. This is not to say that project overspends should be encouraged, especially in a situation when you cannot be sure that injecting money will actually improve anything. It all comes down to risk. What is important is to understand how sensitive a particular project is to slippage and plan accordingly. (Sensitivity analysis is dealt with in Chapter 23.)

Figure 20.1 Cash flow for a project ‘on time’

A two-quarter delay to this project would turn it from being a good investment to a financial embarrassment.

20.1 WHY ARE YOU DOING THIS PROJECT NOW?

Write your list of projects from Project Workout 3.2 on a flip chart. Against each write:

- why you are undertaking the project;

- why it is being done now, rather than later.

Link your answers back to your business plan or business strategy. For internal projects, consider whether you have the right portfolio. For external projects (i.e. those for customers/clients), test whether that work is targeted at a chosen market segment.

20.2 LINKING OBJECTIVES AND NEEDS TO DELIVERABLES

This workout is best done early in the project with the project sponsor, project manager and a selection of key stakeholders comprising those likely to benefit and those who will produce the deliverables. You will need a large paper-covered wall and a supply of Post-It Notes. At the top left write the word ‘How’, with an arrow pointing right. At the top right, write the word ‘Why’, with an arrow pointing left.

- Write the need/opportunity to be filled on a Post-It Note. Place it toward the left of the wall. If there is more than one need, record each of these on separate notes.

- Test these initial needs statements by asking ‘Why do this?’ against each. Write your answer on a Post-It and place it to the left of the original note, linking it with an arrow.

- Continue this until you are satisfied with the resultant core needs. They should match your overall organisation’s business objectives.

- Go back to your original Post-Its and then for each one ask the question ‘How do we do this?’ Write your answer on a note, place it to the right and link it with an arrow. Keep doing this until you have derived a set of ‘create deliverable’ notes, which are sufficient to define the scope of the project.

Notes

- Describe each note using an ‘active verb + noun’ combination. Ensure the verbs are as direct and descriptive as possible, describing an ‘effect’ (e.g. ‘provide’ is not a good word, be more precise). Ultimately the nouns on the right of the chart will be the deliverables.

- Take time to resolve any disagreements over descriptions and placing of notes. These discussions are critical in reaching a common understanding.

- This technique can be used, as above, for overall needs analysis but can also be used on discrete parts of the project as part of detailed design for specific deliverables.

- A variant of the approach is to put the ‘noun’ in the Post-It Note box and the ‘active verb’ on the arrow.

20.3 TRANSFIGURATION

This workout should be undertaken by a prospective project sponsor with the key stakeholders prior to formally starting a project. It is aimed at determining the business objectives for the project in a ‘turn-round’ situation. By capturing people’s fears and grievances you demonstrate you have listened to them and then you concentrate on solving those issues. This approach can be supplemented by Project Workout 24.1, Resolving issues – from breakdown to breakthrough.

- Bring together the people who are unhappy about the current position or antagonistic to what is about to happen. Ask them to tell you all their problems and concerns; write them down on a flip chart. On no account disagree with them – use ‘brainstorming rules’! Take an active interest and help them to remember all the bad things they can.

- When they have had a good moan, ask them to pick the worst half-dozen of the complaints.

- Write the chosen complaints in the top half of a new flip chart – one sheet per complaint.

- For each complaint develop a positive statement which is the opposite of the complaint. Write this on the lower half of each respective sheet.

- Hide away the complaints, by folding over the sheets to show them just the positive outcomes. Ask them:

- when they’d like the world to be like that,

- whether they think it is possible. See what answers you get.

- Ask them what they will hear/see/feel happening that will show them that the world has changed. Their answers help to frame their objectives and help build your conditions of satisfaction.

Caution – objectives gained in this way are only the mirror images of current failures. You should still try to find objectives from visionary people. Published Company Accounts, publicised vision documents and manifesto promises are also good sources for business objectives.