Who Does What?

In simple terms a project needs a person: who comes up with the idea (the originator), who wants the project benefits (project sponsor), who manages the project (project manager) and who undertakes the work (the project team).

‘Even emperors can’t do it all by themselves.’

BERTOLT BRECHT

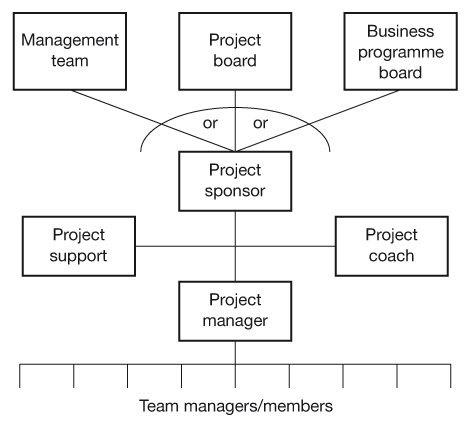

Chapter 2 showed that a process is nothing without the culture, systems and organisation that support it (see pp. 14, 34). Project processes are no exception. Hence, to understand ‘projects’ you need to have a firm grasp of who the players are and what is expected of them. The roles described here are relevant to a single project (see Figure 4.1). Roles required for running a portfolio of projects are described in Part Three.

In simple terms a project needs a person:

- who comes up with the idea – the originator;

- who wants the project benefits – project sponsor and project board;

- who manages the project – the project manager;

- who undertakes the work – the team managers and members.

Appendix B shows, in diagrammatic form, how these different accountabilities interact.

Figure 4.1 A typical project organisation structure

The project sponsor who requires the benefits is supported either by a project board, management team or business programme board. The project manager reports to the project sponsor and is accountable for the day-to-day running of the project. A project coach supports these key roles. All team members report to the project manager.

The players

The originator

He/she is the person who identifies the ‘need’ for a project and publishes it in the form of a proposal. This person can come from any function or level inside or outside the organisation. Ideally, if the idea comes directly from the strategy, the orginator will become the sponsor.

The project sponsor

The project sponsor is accountable for realising the benefits to the organisation. This is an active role and includes ensuring the project always makes sound business sense, involving all benefiting units (and using a project board if appropriate), owning the business case and making decisions or recommendations at critical points in the project’s life. The project sponsor is usually a director, executive, or senior manager.1

Project sponsor

The project sponsor is accountable for realising the benefits for the organisation. He/she will:

- ensure a real business need is being addressed by the project;

- define and communicate the business objectives in a concise and unambiguous way (see Chapter 20);

- ensure the project remains a viable business proposition;

- initiate project reviews (see Chapter 26);

- ensure the delivered solution matches the needs of the business;

- represent the business in key project decisions;

- approve key project deliverables and project closure;

- resolve project issues that are outside the control of the project manager;

- chair the project board (if one is required);

- appoint the project manager and facilitate the appointment of team members;

- engage and manage key stakeholders.

The project sponsor is ultimately accountable to the chief executive/president via a project board (where required) or to an intermediate management team or board.

An underlying principle of project management is that of ‘single point accountability’. This is meant to stop things ‘falling down the cracks’ and applies not only to the management of projects and the constituent work packages, but also to the direction of a project; there should be only one project sponsor per project. In this respect, the term ‘sponsorship’ should not be used in the same sense as ‘sponsoring Tom to run a marathon’, where the objective is to have as many sponsors as possible. If a project sponsor is to be effective, rather than just someone who gives some money, he/she will need to be:

- a business leader;

- a change agent; and

- a decision maker.

The project sponsor as a business leader

Project sponsorship is not merely a ‘figurehead’ role. A sponsor is fundamentally accountable for ensuring ‘why’ the organisation is spending time and resources on a particular project. He/she must ensure that the business objectives are clearly articulated, that whatever is being created is really needed and that this need is fulfilled in a viable way. The project team will have their heads down, developing whatever outputs and deliverables are needed. The sponsor has to keep his/her head up, making sure the need still exists and the capabilities being produced fit the need. This cannot be over-emphasised; current research indicates that a prime cause of project failure is the lack of effective sponsorship and stakeholder engagement (we will come to stakeholders later, in Chapter 19).

The project sponsor as a change agent

Some may see the role of change agent and leader as synonymous. If so, that is good. For others, I have separated these out so it can be related to what many consultants and academics often refer to as ‘the management of change’. Every project will create some change in the organisation, otherwise there is no point in undertaking it! However, some changes are ’easier’ to effect than others as they align with the status quo and do not cross any politically sensitive boundaries. In essence, most of the people carry on as they always have done. Other changes, however, are fundamental and will result in shifts in power bases internal to the organisation or even external, such as in unions, suppliers or customers.

All organisations are ‘political’ to some extent and the greater a project’s scope to change the status quo, the more those involved will need to be tuned in. Whilst projects create change, that change may not necessarily be beneficial to everyone it touches, and this will trigger a political dimension to the sponsor’s role. People’s attitudes to ‘corporate politics’ differ, ranging from believing it is unnecessary through to seeing it as an opportunity. Suffice to say, you must acknowledge the political aspects, understand the sources and motivations of the key players and then develop an appropriate approach to them.

The project sponsor as a decision maker

The decisions a sponsor will need to make fall into two broad types:

- decisions which steer the project in a certain direction;

- approval of certain deliverables.

The first type relates to go/no go decisions at the gates, decisions regarding how to react to issues and changes, and decisions on when to close the project. The second type relates to particular outputs from the project.

If a person is unable to make decisions, the project sponsor is not likely to be a role they will be comfortable with. Most of the decisions which have to be made will be predictable (in terms of timing, if not outcome!) and backed up by evidence. The project documentation, such as business cases and closure reports, are designed to provide the sponsor with the information he/she needs.

THE PROJECT SPONSOR’S TROOPER – THE PROJECT CHAMPION

Quite often a project requires high level sponsorship from either a vice president or even from the company president himself/herself. Unfortunately, senior ranks do not always have the time to carry out all the duties that being a project sponsor entails. Here, it is best if they delegate the role and name someone else as sponsor. Half-hearted sponsorship can be very demotivating for the team and may even lead to the failure of the project. Alternatively, another manager may be assigned to act on their behalf. This person is often a ‘project champion’ who is as committed to the benefits as the sponsor him/herself. In all practical terms, the project champion acts on a day-to-day basis as the project sponsor, only referring decisions upwards as required.

The project board

A project board is usually required for projects which span a number of processes or functional boundaries and/or where the benefits are directed to more than one market segment or function. If no project board is required, the role can be undertaken by a programme board or management team. A programme board has accountability for a set of closely aligned projects. Programmes are illustrated more fully in Chapter 14. Unfortunately, bodies such as project boards are often ineffective, adding little value to the project. It is the project sponsor’s responsibility, as chair of the group, to keep board members focused on the key aspects of the project where their experience can be used to best effect.

The project board

The role of the project board (if required) is to support the project sponsor in realising the project benefits and in particular:

- to monitor the project progress and ensure that the interests of your organisation are best served;

- to provide a forum for taking strategic, cross-functional decisions, removing obstacles and for resolving issues.

A project board is often called a steering group, or steering board.

WHO’S RUNNING THIS ORGANISATION?

Do you often find people in your organisation hunting around for someone to ‘sponsor their project’? If so, who do you think is running the organisation? Surely, it is the accountability of the business leaders (i.e. sponsors) to set the direction and identify the needs that must be met. They should be the ones looking for people to manage their projects, not the other way round. Is your organisation led by its generals or by its troops? Is your project framework going to be a vehicle for change or merely an elaborate suggestion scheme?

The project manager

He/she is accountable to the project sponsor for the day-to-day management of the project involving the project team across all necessary functions. Thus all project managers will need to be familiar with Parts Two and Four of this book. Depending on the size of the project, the project manager may be supported by a project administrator, or office support team (see Chapter 27).

Project manager

The project manager is accountable for managing the project on a day-to-day basis. He/she will:

- assemble the project team, with the agreement of appropriate line managers;

- prepare the business case, project definition and detailed plans;

- define the accountabilities, work scope and targets for each team member;

- monitor and manage project progress;

- monitor and manage risk and opportunities;

- manage the resolution of project issues;

- manage the scope of the project and control changes;

- forecast likely business benefits;

- deliver the project deliverables on time, to budget, at agreed quality;

- monitor and manage supplier performance;

- communicate with stakeholders;

- manage the closure of the project.

The bodies of knowledge of various associations, such as the Association for Project Management or the Project Management Institute, seek to define the attributes of project managers. They are, however, not so easy to apply in practice. To put them in context, consider three levels of project manager competence.

- Intuitive project managers are capable of managing a small or simple project very effectively with a small team. They rely on their own acquired common sense, much of which is inherent good practice in project management. They intuitively engage stakeholders, seek solutions, plan ahead, allocate work and check progress. Many ‘accidental’ project managers fall into this category.

- Methodical project managers are capable of managing larger, more complex projects where it is not possible to keep the whole venture on track using simple tools and memory. Formal methods, procedures and practices are put in place to ensure the project is managed effectively.

- Judgmental project managers can cope with highly complex and often difficult projects. They can apply methods creatively to build a project approach and plan which is both flexible and effective, whilst keeping true to all the principles of good project management.

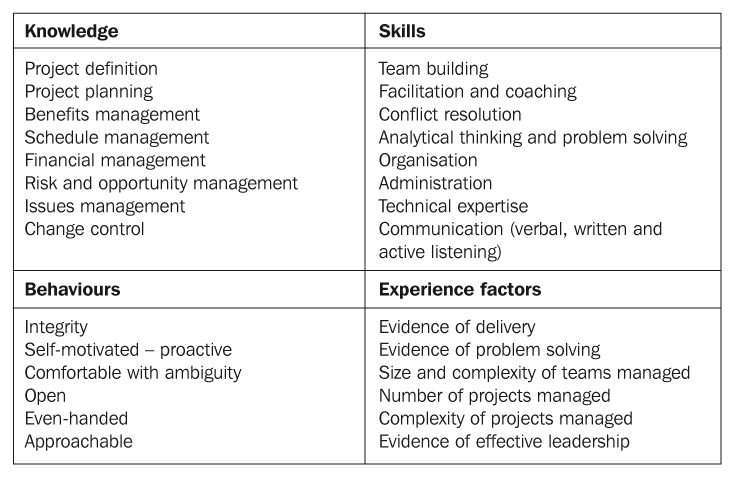

Performance in a role can be looked at as a combination of four factors: knowledge, experience, skill and behaviours.

- Knowledge comprises learning a set of tools and techniques which are unique to project management.

- Skills are the application of tools and techniques.

- Behaviours represent the attitude and style used by the project manager toward team members, sponsor, board and stakeholders.

- Experience measures the depth to which any knowledge, skills or behaviours have been applied.

Figure 4.2 gives a summary of these.

The preceding paragraphs should give the dimensions to look for when selecting a project manager and are sufficient for you to discuss a brief either with other managers or your Human Resources department. However, when it comes down to it, how would you distinguish between people who have similar skill sets? What should you look for or avoid?

Figure 4.2 Attributes of a good project manager

The figure shows those attributes which have been shown to be essential to good project manager performance. The extent to which a person complies very much depends on their level of attainment. You would expect an intuitive project manager to have far less project experience than a judgmental one. Source: CITI Limited.

Good reasons for selecting a particular project manager include the following:

- Inherent enthusiasm. They need to understand the role and what it entails or be willing to learn and have the aptitude to cope. Look for the spark that tells you they really want this to succeed.

- High tolerance of uncertainty. They need to be able to work effectively across the organisation, without formal line authority or rank authority. They need to be able, especially in the investigative stages, to deal with the many potentially conflicting needs and signals as the project hunts its way toward a solution.

- Excellent coalition and team-building skills. People are at the heart of projects, both as team members and stakeholders. If the project manager hasn’t the necessary ‘people’ skills, the project is unlikely to be a success.

- Client orientation. This means they need to understand the expectations and differing success criteria of the various stakeholders, especially the project sponsor.

Poor reasons for selecting a project manager, if taken in isolation, include the following:

- Availability. The worst reason to appoint a person is simply because he or she is available. Why are they available? What aptitude do they have? This tends to happen in organisations with a low level of maturity in project management, as ‘project staff’ are often not seen as part of the normal work of the organisation and having them ‘do something’, rather than ‘nothing’ is seen as more important.

- Technical skill. This can be useful on a project but not essential. The project manager can draw on technical experts as part of the core team. The danger when the project manager is also the technical expert is that he/she will concentrate on the technical area of interest to the exclusion of everything else. For example, a good systems programmer may ignore the roll out, training and usability of a new system as they are more interested in the technical architectures and features.

- Toughness. The ‘macho’ project manager who closely supervises every aspect of the project, placing demand upon demand upon the team (or else!), is the way to demoralise a team. Add to this the likelihood that many of the team may be working part time it may be a fast way of losing the very people who are vital to a successful outcome. Yes, a project manager needs to be emotionally tough and resilient but this should not translate into being a bully.

- Age. Grey hairs do not necessarily indicate a better project manager (although there are very many excellent older project managers). Maturity in project management comes from exposure to a wide range of different situations and projects. Managing a single project over five years is quite different to managing ten projects each of six-month duration. Length of time alone is not an indicator of experience.

The team managers and members

The team managers and members are the ‘doers’ who report to the project manager and are accountable for prescribed work packages and deliverables. This may range from a complete subproject to a single deliverable. It is essential that the full experience of the team be brought to bear on any problems or solutions from the start. In the case of large projects, the project manager may choose to have a small core team, each member of which manages his or her own subsidiary teams either on work packages or subprojects. Project teams often comprise two parts:

- The core team – those members who are full time on the project and report directly to the project manager. A core team size of six to ten people is about right.

- The extended team – those members who report to the core team (team managers) and who may be part or full time.

It is essential that each member of staff working on your project has a clearly defined:

- role and reporting line to the project manager when working on the project (he/she may maintain their normal reporting line for other activities);

- scope of work and list of deliverables (both final and intermediate deliverables);

- level of authority (i.e. directions on what decisions he/she can and cannot take on behalf of his/her line function).

All groups of individuals associated with the project and which make up the team should be identified and listed with their role, scope and accountabilities.

The team managers and members

Team managers and members are accountable to the project manager. The role of team members is to:

- be accountable for such deliverables as are delegated to them by the project manager, ensuring they are completed on time and to budget;

- liaise and work with other team managers and members in the carrying out of their work;

- contribute to and review key project documentation;

- monitor and manage progress on their delegated work scope;

- manage the resolution of issues, escalating any which they can not deal with to the project manager;

- monitor changes to their work scope, informing the project manager of any which require approval;

- monitor risk associated with their work scope;

- be responsible for advising the appropriate team managers and/or project manager of potential issues, risks or opportunities they have noticed.

In addition, a team manager is accountable for directing and supervising the individual members of the team.

Project coach/facilitator

The project coach or facilitator is accountable for supporting the project manager, project sponsor and project board. This may be by pure coaching or by giving advice, facilitation and guidance on project management. Both approaches will help project teams, both experienced and inexperienced, to perform beyond their own expectations. It is a role which is found infrequently but one which can prove extremely effective.

Remember, in business-oriented projects the participants are likely not to be fully trained and capable project managers. They need to have someone who can give them the confidence to work in a way which may be alien to them.

The power of coaching and facilitation

A cross-functional team was put together with the aim of reducing the delivery time for a telecommunications product from ten days to less than two hours. The team comprised people drawn from line, operational roles who had little project management experience. A project coach was employed to facilitate the initiation of the project and to provide on-going guidance throughout the execution. Setup was hard work and many of the team complained that it was wasting valuable time which could be better spent doing ‘real work’. Perseverance and a commitment on behalf of the coach to seeing the team succeed got the team through the early stages and, once the development stage was underway, all of them understood the project fully. At the end, a marketing manager on the project commented to the coach, ‘I wondered what you were doing to us; I now see it was key to have the hassle at the start if we were to actually achieve our objectives.’ Things did go wrong on the project but as all the core team members knew their own role and that of the others, changes could be more easily, speedily and effectively implemented so that the overall objective was met. In fact the delivery time was reduced to an average of 20 minutes.

Project support

Project support provides support and administrative services to the project manager on activities such as filing, planning, project monitoring and control.

The provision of project support on a formal basis is optional. Tasks need to be done by the project manager or delegated to a separate body/person and this will be driven by the needs of the individual project and project manager. Project support could be in the form of advice on project management tools, guidance, administrative services such as filing and the collection of actuals, to one or more related projects. Where set up as an official body, project support can act as a repository for lessons learned and a central source of expertise in specialist support tools.

Project support

Specific responsibilities may include the following:

- set up and maintain project files;

- establish document control procedures on the project;

- compile, copy and distribute all project management deliverables;

- collect actuals data and forecasts;

- update plans;

- assist with the compilation of reports;

- administer the document review process;

- administer project meetings;

- monitor and administer risks, issues, changes and defects;

- provide specialist knowledge (for example estimating, risk management);

- provide specialist tool expertise (for example planning and control tools, risk analysis).

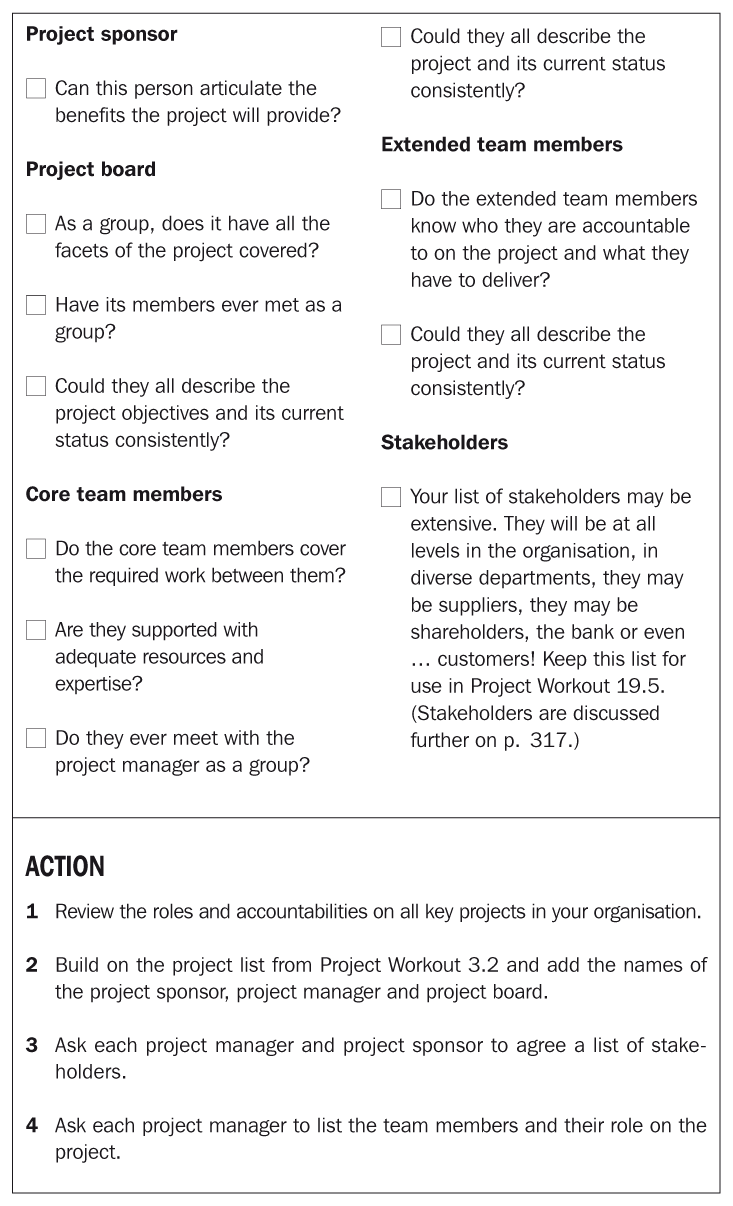

4.1 ROLES AND ACCOUNTABILITIES

This workout is best done with the project team, but may be done by the project manager or sponsor as an exercise in isolation.

- Take any one of your key projects from Project Workout 3.2 and identify who (both individuals and teams) is involved in it. List them, one per Post-It Note. Place these on a flip chart.

- Against each name, write in your own words what that person’s needs or accountabilities are regarding the project.

- On the left hand side of a separate flip chart, list the roles described in Chapter 4.

- Match, as best you can, the names from step 2 to the key project roles described above.

- For those names listed against ‘team member’, divide them into ‘core team member’ and ‘extended team member’.

- If you cannot allocate a person to one of the defined roles, put him/her in a separate cluster called ‘stakeholders’.

Look at the role descriptions described in the chapter again. Do the individuals have the knowledge, skills and competences to perform the roles?

You should have only one name against project sponsor and one against project manager. If not, your roles and accountabilities are likely to be confused. Further, it is not good practice if the sponsor and manager is the same person.

1 The Financial Times Executive Briefing, The Role of the Executive Project Sponsor, by Robert Buttrick (Financial Times Prentice Hall, 2002), looks at projects from the perspective of this senior role. See the ‘Publications’ section of projectworkout.com for more details.