Have I Got the Resources?

Conditions for total resource planning

White space – the freedom to change

How can I meet the three conditions?

How detailed does resource forecasting need to be?

Obtaining resources and holding on to them can be very problematic, especially in functionally oriented organisations, where the balance of power is firmly held by line management. In these circumstances, resources are often committed to projects on the basis of good intention, rather than on good information.

‘You’ve got a goal, I’ve got a goal. Now all we need is a football team.’

GROUCHO MARX

Conditions for total resource planning

In 1993 the University of Southern California analysed 165 teams in a number of successful organisations to assess the effectiveness of teamwork. Two reasons for teams failing to deliver were found:

- Project objectives were unclear.

- The right people were not working on the project at the right time.

In looking for solutions to these two issues, they found that using a ‘projects approach’ gave significant benefits in clarifying objectives (which is just as well or it would conflict with the message in this book!). On the question of resources, they found that having visibility of available resources and obtaining commitment of the required resources was key. In other words, if you haven’t got the right people you can’t expect to complete your project.

Obtaining resources and holding on to them can be very problematic, especially in functionally oriented organisations, where the balance of power is firmly held by line management. In these circumstances, resources are often committed to projects on the basis of good intention, rather than on good information. Consequently, they can be withdrawn, at whim, by the owning department if it believes that its own need is greater than that of the project. The result is that resource and skill shortages do not become apparent until they are a problem. An effective method of resource allocation and commitment is needed, therefore, which meets three conditions:

- Condition 1 – you have a clear view of how resources are being consumed on a project by project basis.

- Condition 2 – you have visibility of the resources available, or soon to be available, within the forecasting horizon of your organisation.

- Condition 3 – commitment of resources should be based on clear information and forms the basis of an ‘agreement’ between the departments providing the resources and the projects consuming the resource.

Meeting these conditions will enable you to anticipate potential resource conflicts before they become a problem.

Many of the problems that organisations face in trying to allocate their resources efficiently come about as a result of some misconceptions regarding projects and resources. These misconceptions are:

- people work only on projects and do nothing else;

- resources are allocated to projects;

- project managers can choose whoever they want to work for them.

In practice you will find that:

- In most organisations, much of the work is not done on projects, but as part of running the business on a day-to-day basis (for example, when I worked on product management, 25 per cent of time was spent on development projects, 15 per cent on general management and administration, 40 per cent on product management and 20 per cent being sick, trained and on paid leave).

- Work is given to people. Your core employees are there all the time and being paid. You pay them regardless of whether they are working or on paid leave. There are some people you can turn on and off like a tap (temporary or agency staff), but I doubt if these are your key people.

- A project manager will state what he/she needs for the project and the line manager will allocate the most appropriate (or convenient) people. The line managers should know their people and their capabilities. They should be competent in the field of work they are accountable for and hence be best placed to decide who will fit a given role on a project.

In the benchmarking study, I found that the organisations that were best at managing and committing their resources were the consultancies. Their systems and processes were well tuned for this. Tight margins require that they have their staff on fee-paying work for as much of the working year as possible. They also need continually to form and reform teams from across the organisation to address the assignments. Further, they are never quite sure when a client is going to require their services but when a client does, they have to respond fast. They, therefore, have a conflict that:

- their employees should be gainfully engaged on fee-paying work, i.e. they need to drive staff utilisation up;

- they need to have enough slack in the allocation of resources to enable them to respond to new requests quickly, i.e. don’t drive utilisation up too high.

(Compare this with the need on business projects to do an initial investigation of a proposal as soon as possible while trying to do as many of the required projects – it’s very similar.) Rather than talk theoretically, I will explain a basic, but very effective resource management method from one of these types of organisations.

The organisation is an engineering consultancy with about 1,200 employees in various locations worldwide. In the past, margins in these organisations were very high and, as long as the people were working on assignments (projects), good profits were made. Management systems did not need to be sophisticated. However, the organisation did have a time-recording capability for all its employees so that time could be booked to assignment accounts and charged on to clients. Time for non-assignment work was also captured, either as process activities (marketing, sales, etc.) or as overheads (training, paid leave, sickness), i.e. the organisation met condition 1 for resource management.

The competitive environment changed and the organisation found itself very rapidly being drawn into a lower margin industry. It was essential to ‘commercialise’ the management systems of the organisation fast if they were to retain control. The first attempt was to collect three sets of data from assignment managers, each required by different central functions:

- The invoicing department wanted a forecast of the invoices which would be sent out so that they could ensure they were staffed up to despatch the invoices quickly.

- The financial controller wanted a forecast of cash due, so that he could manage the working capital required and manage the payment of bills.

- The operations director wanted to know who was allocated to assignments and who was coming free so he knew what work he could accept (resource management).

Needless to say, the assignment managers did not look on these three separate sets of ‘new demands’ kindly. Nevertheless, they did their best.

THE FUTURE ROLE OF FUNCTIONS

If what people do counts more than the function or department they belong to and if you are to use people to best effect anywhere in your organisation, what is the role of the functions? You now know that few changes can be made within a single function in your organisation. You generally require people from a number of areas contributing to the processes, activities and projects you are undertaking.

In the traditional hierarchy, each head of function decides not only the strategic direction of their function, but also what each and every one of his/her employees will do and how it will be done. The danger, if functions are too dominant, is that they will drive the business as they see fit from their own perspective. This may not be in line with the drivers that the organisation leadership wants to effect. The outcome is that the organisation becomes out of balance. For example, efficiency is often seen as a good goal. So also is responsiveness to customer needs. However, the latter may require you to carry excess capacity in order to meet customer needs at short notice. If one function is driving ‘efficiency’ up by reducing capacity while another is creating a proposition around responsiveness there is likely to be a mismatch and dissatisfied customers.

The projects approach, like the current move toward cross-business processes, aligns all the required skills and capabilities around the attainment of a business objective. In the case of a process, the objective is better operations. In the case of a project, the objective is change for the better. Thus, the functions are not leaders in driving the business, but rather suppliers of people and expertise to projects and processes. The accountability of a head of function is to ensure that the right people are available in the right numbers to service the business needs. They will be accountable for pay, employee satisfaction and personal development. Other key roles will start to become apparent. There will need to be those, expert at particular disciplines, who will create strategy, develop and maintain technical architecture, manage projects, or manage people. However, they will not do this just in the context of a single function, but rather in the context of the complete organisation, working wherever needed across functional boundaries to achieve the business objectives.

When looked at together, however, the three discrete sets of information proved very interesting. The forecast of work, in hours, could be multiplied by a factor to give a good approximation of the invoice values. The cash received should be the same as that invoiced (forgetting bad debts). The only difference between the three sets of figures should be timing:

- the time from doing the work to invoicing represents work-in-progress days;

- the time between invoicing and cash received represents debtor days.

However, even taking account of the timing difference, the three sets of figures could not be reconciled. The forecast was unreliable and inconsistent.

The solution they implemented to deal with this divergence was very simple. They asked for the same data, but had them collected at the same time on two linked data sheets:

- a manpower sheet;

- a financial sheet.

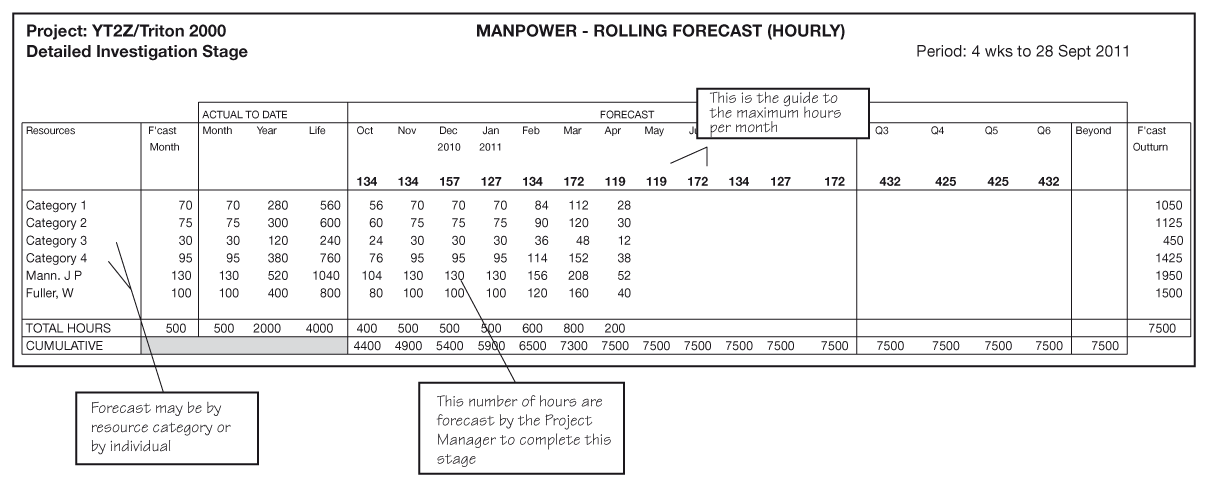

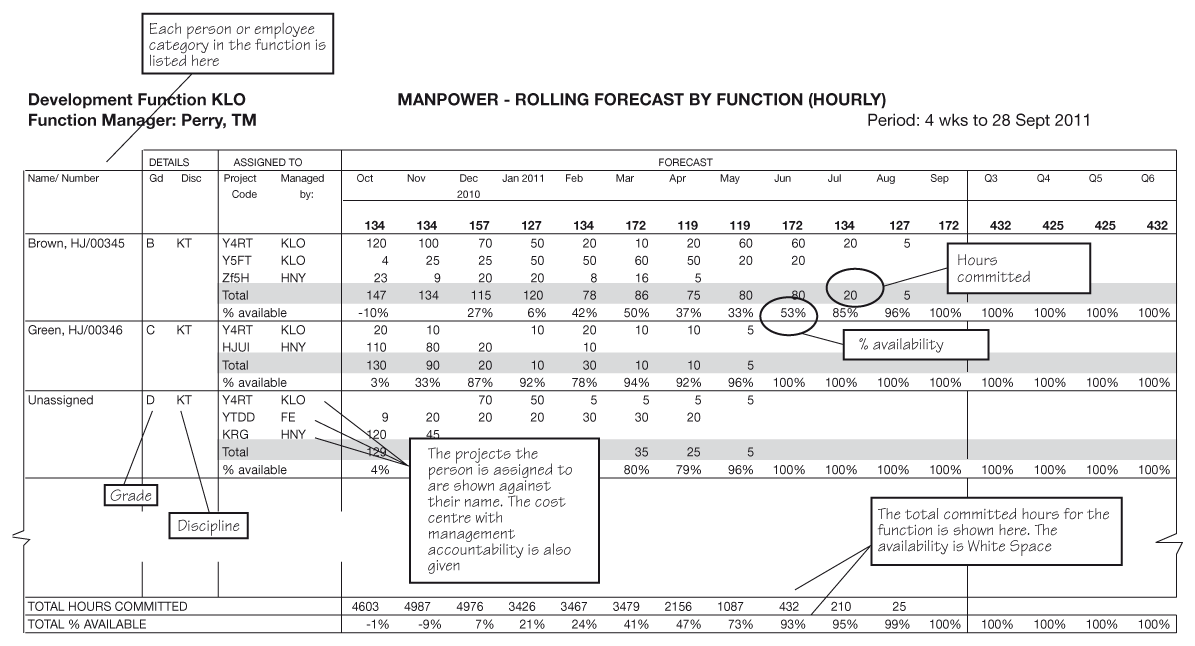

The manpower sheet: each assignment manager listed the people (by name, or by grade/discipline) required on the project. Against each, he forecast the number of hours each would book in a given month. There was a cap on the maximum hours each month to provide for unexpected work and ‘down time’. (Look ahead to Figure 16.2 for an example.)

The financial sheet: the hours from the manpower sheet were then costed at actual pay-roll rates and entered into a second financial sheet as time costs (cost of labour). To this sheet, the assignment manager added the forecast of non-labour costs. He also added, at the top of the sheet, the forecast of invoices required to be sent out, with a line below showing when the cash would be received. In short, they ensured that all necessary data were collected at the same time, using the same form. The whole forecast was input to a computer, added and sorted so that summary reports and analyses could be obtained. The result was consistent data giving consistent forecast reports. No matter who needed the information, they knew it was compatible with that used by others for different purposes. It was so good that the marketing department was able to provide a full analysis of the business on a segmented basis every month, both historic and future. Previously, such an analysis used to take three months to complete.

One of the reports produced from this system was for the heads of function: they each received a listing of all the people within their department, together with a list of which assignments they were committed to and for how many hours each month. The organisation, therefore, had visibility of its future resource needs, i.e. the organisation met condition 2, visibility, for resource management. (Look ahead to Figure 16.3 for an example.)

The first few months of operation were problematic as people adjusted the forecasts to take account of what they had learned. However, after a short time it stabilised and became a reliable source of management information. From thereon, whenever the organisation had a request for work from a client or was invited to tender for work, it could assess whether it was likely to have the resources available to meet the need and/or design the bid to fit around its known commitments. Also, as the requesting project completed the resource forecast, this became the ‘agreement’ between the project manager and the supplying department. i.e. they fulfilled condition 3 for resource management.

The frequency of reforecasting was set at quarterly intervals as it was expected that the effort of constructing the forecast would be too onerous on a monthly basis. The assignment managers were given the option to do it monthly if they wanted to. In practice they all chose to do a monthly forecast as it was easier to maintain and amend on this more frequent basis rather than start at a lower level of knowledge on a quarterly basis.

This organisation:

- knew what each project and activity in the organisation consumed by way of resources (condition 1);

- had clear visibility, at a high level, of its resource availability (condition 2);

- made future commitments on the basis of knowing what was currently committed and who was available without compromising previously made commitments (condition 3).

In short, it had achieved a level of knowledge about the application of company resources that many organisations can only dream of. Did this process provide reasonable figures? The financial controller predicted the year-end results, six months in advance, to within an accuracy of 2 per cent, excepting extraordinary accounting items, and the company was able to successfully arrange finace well in advance, based on reliable figures. While individual assignments within the portfolio exhibited a fair degree of instability in forecasting, the population, as a whole, was very stable.

This example dealt with a consultancy organisation, where it is crucial to have a tight hold on resources. When one moves into the manufacturing or the service sector, the management of resources becomes less visible and is often hidden within functional hierarchies. Certain parts may be exceptionally well managed (such as individual manufacturing units, warehousing, telephone call centres) but these are usually contained within a given function and deal with day-to-day business rather than change. Business projects frequently draw on resources from across an organisation, not just from one function. If just one part is unable to deliver its contribution to a project, the entire venture is at risk. Few organisations have, or yet see the need for, the capability to manage their entire employee workforce as a block of resources that can be used anywhere, at any time, just as in a consultancy organisation. However, as in consultancy organisations, managers should make sure that their people are being applied to productive work, rather than merely playing a numbers game with head count and departmental budgets – this just leads to suboptimisation, which may be of no benefit at all (see Chapter 20).

White space – the freedom to change

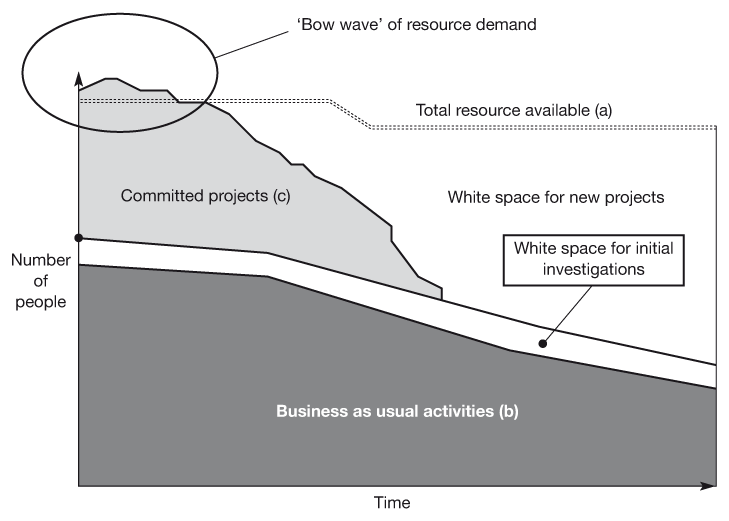

The gap between what your resources are committed to and the total resource you have available is what I term ‘white space’. It is the resources that you have not yet committed to a given activity or project. If you fulfil conditions 2 and 3, you will know your white space:

White space = resources available – resources already committed

In the very short term this should be small. It will grow as you look further into the future.

White space is fundamental to a organisation’s on-going health. If you haven’t any in the short to medium term, you are paralysed. You have no one available to change the business to meet new threats or exploit new opportunities unless you withdraw them from previously committed work. White space gives you the resources to effect change in the future. ‘We are in a fast moving environment’ is the common cry nowadays. If this is truly the case, then you need to ensure that you have ‘white space’ resources ready to meet future needs. You know the people will be required but you are not yet sure exactly what for. If you have no people to change things, things won’t change.

White space must cater for two distinct needs:

- First, it must cover the need to undertake initial investigations resulting from new proposals. These people must be available at very short notice and must be highly knowledgeable if the investigations are to have any value.

- Second, you need the resources to undertake the projects themselves, following approval at the Detailed Investigation Gate.

Compare the former to a company putting a bid together – if this is done by inappropriate people, the bid may be lost or the company may have committed itself to a financial disaster. Just because business projects are ‘internal’ it does not mean you need not apply the same rigour as you would with external matters. It’s your organisation’s future at stake in both cases.

Figure 16.1 represents ‘white space’ in graph form. The figure could apply to a complete organisation, a division, a function or whatever. However, unless you can build this picture you will be taking risks every time you need to set off another initiative.

Figure 16.1 White space

White space is the gap between the resources you have (a) and those already committed (b + c). In the very short term this should be small. It will grow as you look further into the future. Notice the short-term bow wave which results from optimistic demands to the immediate needs.

How can I meet the three conditions?

The extent you need to employ formal systems to collate the past and future use of your resources depends on your organisation. At one extreme, you will need time recording to know what people have been working on, at the other you can rely on the line managers filling that gap.

Time recording

Those organisations which require time recording for other business critical needs will, like as not, already have it. Few organisations who don’t, won’t. It is an emotive system to implement. It can look and feel like bureaucracy gone mad. Some people are so against it they will leave a organisation rather than fill in a time sheet. It is often bound up in emotive words such as ‘trust’. ‘If you can’t trust me to work on the right thing, I don’t want to work for you.’ Few finance or marketing functions are on time recording. However, it is very common in engineering and technical departments. Despite this, time recording can be the key to making a flat structure work. It allows people to be accountable for activities and projects which range far beyond their functional patch. It can enable job enrichment. It also enables you to delegate more without losing visibility and control. If implementing time recording, you need to balance the cost of doing it with the information gained. Consider:

- what the reports provided by the system will tell you;

- how they are structured;

- who has access to them.

Also consider the timing for implementing a time-recording system. The only reason you have the system is for the reports – if they don’t help you meet your overall needs at the moment, don’t do it yet. If the basic understanding and acceptance of their use is not in place you will have an uphill struggle to make them work. Preferably, you should wait until those within your organisation (project sponsors, project managers, functional resource managers) have identified the need themselves.

Finally, remember that if you don’t have some kind of time recording, you won’t know how much your projects are costing. Consequently, you will rely on line management reports for controlling costs, which in turn keeps the balance of power firmly in the line management camp rather than shifting it toward the project view of life. Time recording, if properly implemented with appropriate reporting, will give you an extra degree of freedom to manage your business.

Manpower forecasting

Manpower forecasting is a natural follow-on from time recording. It is merely a prediction of how many hours will be booked by whom against a particular activity or project. Forecasts can be created by one of three different roles.

| Forecast made by | Comment |

| Each individual forecasts his/her own time input based on what he/she has already been briefed on and is committed to doing | In most cases, individuals will not have sufficient visibility of the work needed. They will only forecast the work they have been told to do, not what their managers know needs to be done, but for which no briefing has as yet been given. Forecasts on this basis will be very short term and hence of limited use |

| The resource manager forecasts the people required to meet commitments already made | This lets the ‘supply’ side drive the forecast. This means that the estimates are likely to be good BUT unless well coordinated with every project manager, the timing may be very wrong. The total of such forecasts may show no deficit of resources, but the functions may have made choices regarding the project priorities, which are not rightfully their decisions to make |

| Each project manager forecasts the people who he/she expects and requires to work on the project based on the project plan (see Figure 16.2) | This lets the ‘demand’ side drive the forecast. Estimates will match the plan timescales and should be agreed with the individuals on the project team. The total of these forecasts may show that certain resources are allocated beyond their capacity. This is good to highlight, then a business decision can be made to decide how to deal with the conflicts (see Figure 16.3) |

On the whole, the third method is more likely to serve the needs of the business than the other two. It allows the project managers who are driving the change to set their demands in accordance with their business objectives. It highlights any conflicts and enables a business decision to be made, rather than one being made by the limiting function. Further, it allows the project manager to increase or decrease the demand for resources openly.

In Chapter 15 the principle was: ‘Having decided to do a project, do it. But stop if circumstances change.’ In other words, the project manager continues to flex his forecast of resources to complete the project, based on current knowledge. If the manpower forecast is costed and tied into financial forecasts you can be sure that the project will be reviewed if its cost exceeds the sanctioned amount. The business managers (e.g. project review group) can then make an assessment of whether the project should continue. It is their decision, not that of the functions supplying resource.

A major pitfall of putting in systems to enable you to have visibility of your resources is that they can be made too complicated. Take the following scenario:

- The project schedule and scope drive resource needs.

- You can assign resources in project plans using project-planning software and obtain a profile of who is required and when.

- This can be downloaded into a central database and analysed for the organisation as a whole.

- Resource conflicts are spotted by the ‘system’, which, based on priority rules, automatically levels the conflicting resources by moving lower priority activities back in time.

- The output from the global resource analysis is fed back to the individual project plans, which show the resultant slippage.

There is software that can handle all this in an integrated way, so, no doubt, there are organisations who manage it this way. However, this level of integration and automation is neither always necessary nor always desirable. For example, it would mean that every project would need to use the same, or closely compatible, planning software and be fully resourced at activity level. On its own, this has dubious value, when all you need is ‘visibility’ of resources such that you can make decisions on overall resource availability. Detail is not necessarily needed.

Provided that you use the same high level work breakdown structures and projects as the basis for the forecasts, the resources can be held in a separate, simpler database. You use this to analyse and report on those resources where demand looks as if it will exceed capacity – this in turn tells you which projects may come into conflict. The project managers and the resource managers of the contentious projects and resources can then discuss and agree how the conflict should be handled. If they cannot agree, the issue should be escalated to the project review group. There is no need for sophisticated analysis and resource levelling rules – managers can manage it.

When you add up the total of resources required you will often observe a ‘bow wave’. That is to say, over the short term, the demand for resources exceeds availability (see Figure 16.1). In systems I have seen this always happens. Project managers are optimistic about the work they believe will be done in the next month and not enough account is taken of the reactive work that people have to do in addition to their project duties.

Placing a ‘cap’ on the maximum hours forecast per person is a simple and effective way of dealing with the ‘bow wave’. Assume that a month has four weeks, each of 36 hours, i.e. 144 hours. It is highly unlikely that anyone will actually book 144 hours against a single project on his/her time sheet. It is even less likely that a large population would all book 144 hours; some would be sick, be assigned to urgent work elsewhere, go on training courses, attend a presentation to a key customer, or whatever. By making a simple rule that if a person is full time on a project, you forecast only 85 per cent of 144 hours (122 hours) and build in an allowance for this.

By depressing the maximum forecasting capacity, you allow a contingency (white space) which allows you to do other reactive work or overrun current work without compromising the plan. Experience with forecasting will tell you the right percentage for your organisation.

Figures 16.2 and 16.3 show a typical manpower forecast for a project and a typical report on resource demand for a function.

Figure 16.2 Manpower – rolling forecast by project

This is a typical report on which manpower needs can be forecast. In this case, the figure shows the forecast for the detailed investigation stage of a project. It shows, on the left, the actual hours already booked to the stage and, on the right, the forecast hours and total. The guide for the maximum hours is shown below the date line. If this report is costed it provides the data required for the time cost line in the financial forecast (see Figure 21.4). (Adapted by kind permission of Professional Applications Ltd, UK.)

Figure 16.3 Manpower – rolling forecast by function

Once all the project manpower forecasts have been collated, they can be sorted to give each line manager a listing of the people in his/her department or function, stating to which projects each is committed. (Adapted by kind permission of Professional Applications Ltd, UK.)

How detailed does resource forecasting need to be?

High level forecasting versus detail

The objective of resource management, in the context of portfolios of projects, is to have sufficient visibility of the use and availability of your resources to enable you to commit, with confidence, to starting new projects without compromising the completion of existing projects. It follows then that the forecast does not need to be fully detailed. In fact, as all forecasts are, crudely, a range of very good to very poor guesses, the likely deviations in elements which make up the forecast can be very significant while not affecting the total figure much at all.

Forecasts can be on two levels:

- high – this is equivalent in manufacturing of a master production schedule;

- detailed – this is equivalent in manufacturing to a shop schedule.

It is the high level forecast that you should be concerned with in managing portfolios of projects. The detailed forecast is the accountability of the line and project managers; they decide when the work is actually done and by whom. You should not try to combine the two! In the example I used to explain resource management, the organisation used the following for its high level forecasting:

- forecast, by person or skill group/grade in hours;

- per month, for the next 12 months;

- per quarter, for the following year;

- per year, for the next 3 years

This was in the context that at the start of any financial year this organisation had 50 per cent of its resources for the year already committed. The reason they used hours was simply because that is the basis on which they charged their clients and hence how their time sheets were completed and actuals were reported. Their forecasting frequency was monthly; weekly forecasts would have given little, if any, extra value. However, their manpower (or time sheet) frequency and reporting was weekly. Monthly was too infrequent as deviations from plans would be spotted too late for corrective action to be taken.

Sales pipelines are very difficult to estimate especially in industries where the buying pattern is a few large purchases rather than the mass market consumer pattern. An industrial engineering organisation had a pipeline of about 350 prospects, totalling potential revenue of £300m, which, after factoring in the probability of the customer wanting to proceed and the probability of the bid being won, totalled £50m. Despite this being made up of inputs from six different people, in six different divisions on three continents, one third of the prospects churning every quarter, and potential sales and win probabilities changing frequently, this pipeline stayed very consistent in total displaying little major shift month on month.

In contrast to this, another organisation, at the start of the financial year only had 25 per cent of its resources for the year already committed. They, therefore, used to forecast by person only, in days per week. They used ‘days’ as their measurement unit as, again, that was how they charged their clients and hence how their time-recording system captured and reported the data. Their frequency for forecasting was weekly for manpower and monthly for other costs.

Avoiding micro planning – a solution by applying constraints theory

The primary constraint for a project is usually the resource that can be applied. No resource equals no progress. We also know that micro planning every activity for every person on every one of maybe 50–500 projects is likely to be a fruitless exercise. Reality changes too fast and estimating is not that reliable. So how can we find a way through this such that our estimates and our commitments to undertake the work are realistic?

Every system, process, or organisation has a constraint which limits how much it can achieve (its throughput). In corporate, multiproject environments, there is a single department or work group which is the constraint. In very complex organisations it may be very difficult to identify who this is; however, most people intuitively feel where the problems lie. You hear it in their language, ‘Oh, it’s those people in IT’, or ‘we’d better design this so Technology don’t need to be involved’. Some people actually argue that you could assume there is no resource constraint at all; we just spend our time flitting from task to task in a complex round, wasting energy. They say if we organised better, there would be plenty of resources to do what we really need to do. Others say there are many constraints, not just one, each one sheltering behind the other. Whatever your view, be you a purist ‘there is only one constraint’ person or a realist saying ‘it’s all a constraint!’, the problem remains and needs to be addressed.

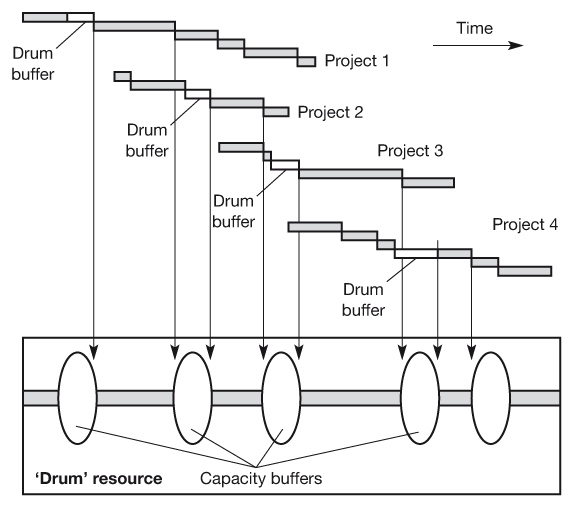

A solution lies in the practical application of the Theory of Constraints. If it is so difficult to find the bottleneck, simply choose a department to be the appointed constraint. Then plan the workflow through this single department to ensure maximum throughput. This means ensuring:

- they receive early warning of work;

- they receive the work as soon as it is ready (no hand-off delays);

- they work only on this (or a defined minimum number) and clear it as soon as possible (that is to say, they avoid bad multi-tasking).

We also need to ensure that delays on one project do not have a knock-on effect on all subsequent projects. We do this by ensuring that between each project, the resource has sufficient safety margin built in to absorb the routine, ‘unexpected’ delays. This is called a capacity buffer.

By protecting the constraint in this way, we stagger the flow of projects in the organisation. We only need to schedule this one resource fully. The constraint becomes in effect a drumbeat to which all other departments march. We can plan projects independently of each other but, by tying them to the ‘drum’, we are able to stagger them in a rational way. The safety (or buffers) provided around the drum resource also provide safety time for work in other departments. Figure 16.4 illustrates this.

- Planning is used to resolve as many problems as possible as early.

- Monitoring during execution is done by managing the buffers.

- There would need to be a strong hold on when projects are released for work; this would be the accountability of the project review group (see p. 188).

If applying this method, individual projects should also be planned in such a way as to increase the reliability of delivery. This is discussed in more detail in Chapter 21 and is the subject of Eli Goldratt’s Critical Chain (North River Press, 1997).

Figure 16.4 Building project timescales around the drum department

The projects are scheduled so that work required in the ‘drum’ department is done in logical sequence without bad multi-tasking. A drum buffer in each project protects the resource from delays within each project. A capacity buffer protects the knock-on effects of delays in one project on all downstream projects.

WHO IS RESPONSIBLE?

This critical chain solution is not simplistic and is not an easy one to put in place. It requires some fundamental changes in behaviour:

Senior executives will have to stagger the release of new projects and new project stages. (Most havoc in multiproject environments is wrought by top managers wanting ‘just one more … NOW!’)

Resource managers will have to reduce bad multi-tasking in their departments (perhaps no more favours!).

Team managers and members will have to undertake their work as fast as possible, ensuring a smooth handover.

… and organisations in cash-rich industries will find this more difficult because there is little financial imperative to change behaviour.

16.1 WHAT’S YOUR ‘WHITE SPACE?’

This workout is for you to use as a discussion point or to identify the capacity your organisation has available to change itself. Assume that any projects to change your current way of working need to be managed and staffed from within your current head count. Try to construct a picture, as in Figure 16.1. As a start, look 12 months ahead only.

Hints

Break up the problem by function if this helps.

Use the list of projects you derived from Workout 3.2 – number each project.

Try to cluster similar groups of people together and build the picture in the following order:

- total head count (a);

- people (either grouped or as individuals) running the current operations (processes) (b);

- people (either grouped or as individuals) working on projects which are currently in progress (c).

Your percentage of white space is (a – (b + c)) / a %;

Consider how fast your business and competitive environment is moving and in this context discuss the following points:

- Will the amount of white space you have allow you to develop enough new products and sufficiently improve your operational and management systems and processes to maintain or enhance your position in the market?

- How far into the future does white space become available? If you had a requirement NOW, how long would you have to wait before you could start working on it without displacing any of your current projects or activities?

- Is there hidden capacity in your business? How do you know?

- Do you have any people who can be deployed quickly onto new projects and who probably do not know what they will be doing next week (i.e. resources for initial investigations)?

- Have you ever started off a set of change projects or initiatives which people say they are keen on but which fail to deliver because insufficient time is made available for them? If so, what does this tell you?