2 Recruitment and retention

Renewing and retaining the stock of human resources are a primary task for organisations, and include all the considerations and activities involved in the sequence of attracting, selecting, starting new employees, and retaining the best. Done well, it can have an immediate and beneficial impact on performance when talented staff are taken on to carry out urgent and important tasks beyond the capacity of existing staff. Long-term benefits come about through recruitment over time of new employees with relevant aptitudes, abilities and motivation, capable of being developed into a high performance workforce. Because organisations consist of people, and because it is people, and only people, who can achieve success or failure, the success of an organisation is determined sooner or later by the calibre of its recruits and by the effectiveness of its recruitment and selection policies.

The process of recruitment encompasses a number of stages. Of primary concern is the development of a reputation as a good employer who attracts good quality applicants. Because selecting the best applicants merits a chapter on its own, a chapter on selection and occupational testing follows this chapter, and ideally the two should be read in conjunction.

Recruiting staff is, however, only one side of the coin. Retaining them is the other. Losing good staff represents a major loss of the investment that has gone into recruiting and training them, as well as having a serious impact on the work of their teams and departments. A positive policy on retention is therefore vital, and steps to achieve this are outlined later in this chapter.

2.1 Recruitment policy

The aim of a policy on recruitment should be to locate and attract good quality applicants and to make valid, reliable, and cost-effective decisions about whom to select. The first consideration is the best way to attract good quality applicants.

Whether good quality applicants apply for vacant positions depends on a number of factors. Among the most significant are the following:

• the reputation of the company as a good employer;

• how well the vacancy has been advertised;

• the attractiveness of the salary and conditions of service;

• whether potential applicants think they can do the job;

• whether the job looks interesting and satisfying.

The first consideration is the manner in which an organisation gains a reputation as a good employer. Large UK organisations such as Marks & Spencer, ICI, British Gas, and the National Health Service enjoy differing reputations as employers. Small firms likewise enjoy differing reputations in their local labour markets. While it takes years to build up a reputation as a good employer, reputations can be lost in months or even weeks by injudicious employment decisions, such as the well-publicised sacking of a group of employees carried out in a harsh and unsupportive manner.

The head of external liaison for British Airways has been quoted as saying that potential employees are as likely to be influenced by the overall image of a company as by the salary mentioned in an advertisement.1 In a reported survey of 1000 employees, staff were asked to identify the five most important things they looked for in a job: 66 per cent said having an interesting and enjoyable job, 52 per cent said job security, 41 per cent said feeling they had accomplished something worthwhile, and 37 per cent said basic pay. Other staff surveys have found similar results.2

Recruitment policies need to be reviewed at regular intervals to ensure that they are offering the conditions and job opportunities that good applicants are looking for. Steps to follow in offering competitive salaries are examined in Chapter 12.

2.2 The labour market

To be effective, recruitment must take account of labour markets at both local and national levels. At local levels, this means gathering information about the supply and demand for recruits within an area defined by daily travel-to-work patterns. Manual workers are frequently reluctant to work more than five miles from where they live, while white-collar staff will travel further, either by public transport, if it is good, or by their own transport. Within this local labour market area the supply and demand for staff will be influenced by expansion and contraction by other employers, the rate at which local schools and colleges send young people into the labour market, new housing developments, and changes in public transport patterns. At national level demographic change and the entry of more women into the labour market are currently significant factors. Some companies rely on large intakes of school leavers every summer. Engineering companies may depend on an intake of new engineering graduates every autumn. From time to time various skill shortages affect the national labour market, especially during economic upturns, causing employers to complain bitterly, even though some of these skill shortages are a direct consequence of employers cutting back on training programmes in previous years.

Demographic change is the easiest national trend to anticipate because it is so well documented, yet employers are still caught out. The recent decline in the number of school leavers has been caused by the drop in birth rates 15 to 20 years ago. Because this decline has coincided with economic recession it has not had as much impact as was anticipated.

The current evidence is that while fewer young people are entering the labour market, more women are seeking employment, particularly on a part-time basis. Women are making up an increasing proportion of the labour force, although nearly half the women are in part-time jobs. More men are also in part-time jobs. In 1986, less than 8 per cent of mature men were in part-time work: ten years later it was nearly 20 per cent, according to the Government’s Labour Force Survey. The cumulative drop in the workforce over the 5-year period 1990–95 amounted to 492 000 people. The number of men in the labour force fell by 498 000 and the female workforce grew by 6000. Since 1971 the number of women in the labour market has risen by almost a third, from 9.4 million to 12.1 million in 1995. The male workforce is, at 15.6 million in 1995, effectively the same as in 1971.

It is forecast that the current population bulge of workers in the 25-44 age range will gradually work its way upwards, creating an older workforce. There will be a fall of 1.2 million in the under-35 range. Fewer people are expected to enter employment in the next five years, partly for demographic reasons, partly because more young people will stay on in education.3 Over the five years from 1995 to the end of the century, the UK labour force is projected to increase by 807 000, and by the year 2006 to rise by some 1.5 million. Most of this rise is forecast to be among women.

In the UK full-time workers have the longest working week of any state in the European Union. More than a third of male workers clock up over 48 hours a week. The European average working week for men is 41.1 hours, compared with the British figure of 45.4 hours. If staff shortages are anticipated, companies have a variety of options to consider, of which putting up rates of pay is only one, and may be self-defeating as other employers follow suit. Other options include:

• improved training;

• improved retention of staff;

• improved relations with local schools and colleges;

• more flexible use of labour;

• a more positive attitude to minority ethnic groups;

• employment of older workers.

2.3 Employment costs and the recruitment process

Employing people costs money. A decision to employ someone is equivalent to an investment decision costing thousands of pounds. In addition to basic salary, indirect benefits such as insurance, holidays, and occupational pensions can add another 30 per cent to employment costs. Then there is the cost of providing office or factory space, equipment and machinery. Add to this the cost of recruiting, selecting and training each new employee, and the costs mount up again. A basic annual salary of £15 000 becomes a cost of over £20 000 a year, plus possibly a further £5000 in equipment and support services. Initial recruitment and selection costs can easily add at least another £1000 per head. Because employees can no longer be hired and fired at whim, and are protected by employment legislation, employment costs should be treated as quasi-fixed costs in accounting terms, rather than variable costs.

Consider also the likely results of a bad selection decision. One ‘bad apple’ can soon upset others in the barrel. A bad employee can upset colleagues, customers, supervisors and subordinates. The result is further cost. Good selection pays a dividend; poor selection costs money.

All of this adds up to the need to give careful consideration before proceeding with employment. Is it essential to fill the vacancy? Can the work be redistributed? Are there suitable internal candidates? Does our human resource plan support recruitment at this time? A sensible sequence for tackling recruitment and selection that takes account of these important questions is provided in Figure 2.1.

Figure 2.1 Planned sequence for recruitment and selection

2.4 Advertising for staff

There are many sources of potential recruits, ranging from respondents to factory gate notices, relatives and friends of existing employees, Job Centres, advertisements in the media, and employment agencies. Some offer free services, such as Job Centres, others, like advertising, are expensive. Over a period of time the HR department builds up a record of the cost and effectiveness of different sources of applicants to determine which offer best value for money.

Advertising for staff is big business. Nearly £470 million was spent by employers and their agencies in 1987, before the onset of the subsequent economic recession, and the figure is now considerably higher.4 As a result, a sophisticated and thriving business has grown up. If use is going to be made of advertising agencies, care has to go into their selection. The professional body for UK advertising agencies is the Institute of Practitioners in Advertising (IPA), who operate a register of members. If a large-scale advertising campaign is planned, selected agencies can be asked to make presentations to the company, with the most convincing one then appointed. If occasional press advertisements are planned, then it is a good idea to appoint an agent to advise on the advertisement, to set it in copy form, and to place it in the desired newspapers or journals. Agencies book space in advance in the press, and it is frequently impossible to place an advertisement at short notice unless one goes through an agent. Agencies take a commission from the press, and therefore can frequently offer a good value service to employers.

What does a good advertisement include by way of information? More importantly, what do potential recruits want to see in advertisements? Evidence from surveys indicates that these are the priority items:

• place of work;

• salary;

• closing date for applications;

• how to apply;

• relevant experience;

• qualifications;

• duties;

• responsibilities;

• something about the organisation.

Advertising for staff is a form of selling — selling the job and selling the company in order to achieve the desired response.5 It is therefore a good idea to start by asking the question: why might somebody want to do this job? Selling points can then be listed. A typical list might be: job interest, training provided, remuneration, technology, location. Following this, decisions can be made on the main headline, sub-headings and copy. The instructions on how to apply need to be clear. Today styles of advertising tend to be colloquial. Pomposity is avoided and language is kept simple and factual. Synergy with the overall corporate advertising style is desirable. Recording and analysing the results of advertising campaigns enable further advertising to concentrate on those channels that have demonstrated their success.

2.5 Short-listing

For most vacancies the objective of a recruitment campaign is to create a short-list of suitable candidates who match the requirements of the job specification. Provided an outline of essential and desirable requirements has been listed in the manner recommended (in the next chapter), a simple matching process can be carried out, matching the applicant’s profile against those required by the job. If large numbers apply, however, this can be time-consuming, and an indication that the advertisement was too loosely worded.

The matching process is facilitated if application forms are designed so that the headings match job specifications. They also need to be designed with an eye to the organisation’s current information systems, because personal data on the application form can be used for record purposes should the applicant be appointed and commence work. Factors such as education, qualifications, work experience, training, and special skills feature on most application forms, plus space for statements on health and disabilities. Personality, however, remains a contentious area. Space is normally provided for a description of leisure interests; this may provide some indication of personal characteristics, especially with school and college leavers (the subject of personality in the context of psychometric testing is addressed in the next chapter). It is also useful to leave free space for candidates to indicate why they think they are suitable for the position. Larger organisations employing a range of staff may need more than one application form. Forms for relatively straightforward work, such as manual work, can be kept simpler than the forms needed for more demanding professional and supervisory positions.

2.6 ‘The psychological contract’

The culmination of a recruitment process is normally a contract of employment. In the UK a legal contract has to be issued within strict time limits in the great majority of cases, and the manner in which this has to be drawn up is examined in some detail in Chapter 9. However, new employees commence employment with a wider set of expectations than those encompassed in the formal contract of employment. Employers in turn have a set of expectations concerning the behaviour of employees that is wider than the formal contract. Expectations on both sides are shaped by societal norms, local culture, and custom and practice. Western society is individualistic, and hence the employment relationship focus is normally on an individual’s relations with his or her employer. Therefore the set of expectations on both sides is termed a ‘psychological contract’. The significance of this ‘contract’ lies in the impact it can have on behaviour, job satisfaction, motivation and performance, and hence on the successful implementation of corporate strategy. This is brought out in Figure 2.2.

Figure 2.2 Psychological contract, HR practices and organisational strategy

Source: Robinson, Kraatz, Rousseau, Changing obligations

Various definitions exist. Most refer to something that is essentially subjective, based on people’s perceptions, and mention such matters as loyalty, trust and recognition. It is generally accepted that mutual obligations are the essence of this psychological contract.6 Obligations have been usefully defined as follows:

beliefs, held by an employee or employer, that each is bound by promise or debt to an action or course of action in relation to the other party. These obligations may derive from explicit or implicit promises of future exchange or reciprocity. Each party possesses his or her own perception of the mutual obligations defining a relationship.7

Interest in this matter has been heightened by the recent debate over whether loyalty still exists within corporations, and whether mutual trust between employers and employees has been undermined by corporate downsizing and delayering. While some observers lament the passing of loyalty and trust, others welcome a new era in which change is the order of the day, and employees can take control of their own careers.

Recent research in the UK indicates that a higher level of confidence in management prevails than recent events may have led one to expect. A survey carried out on behalf of the IPD in 1996 of a random sample of working people found that 82 per cent considered their employers to be fair, 72 per cent were positive on the issue of trusting their employers, and 67 per cent expected to still be with their companies in five years’ time. The overall results lead to the conclusion that the psychological contract is still perceived in traditional terms by most working people. Perceptions were most positive in those companies that had implemented modern ‘high commitment’ HRM policies, and least positive amongst the semi-skilled and un-skilled, and those on temporary contracts.

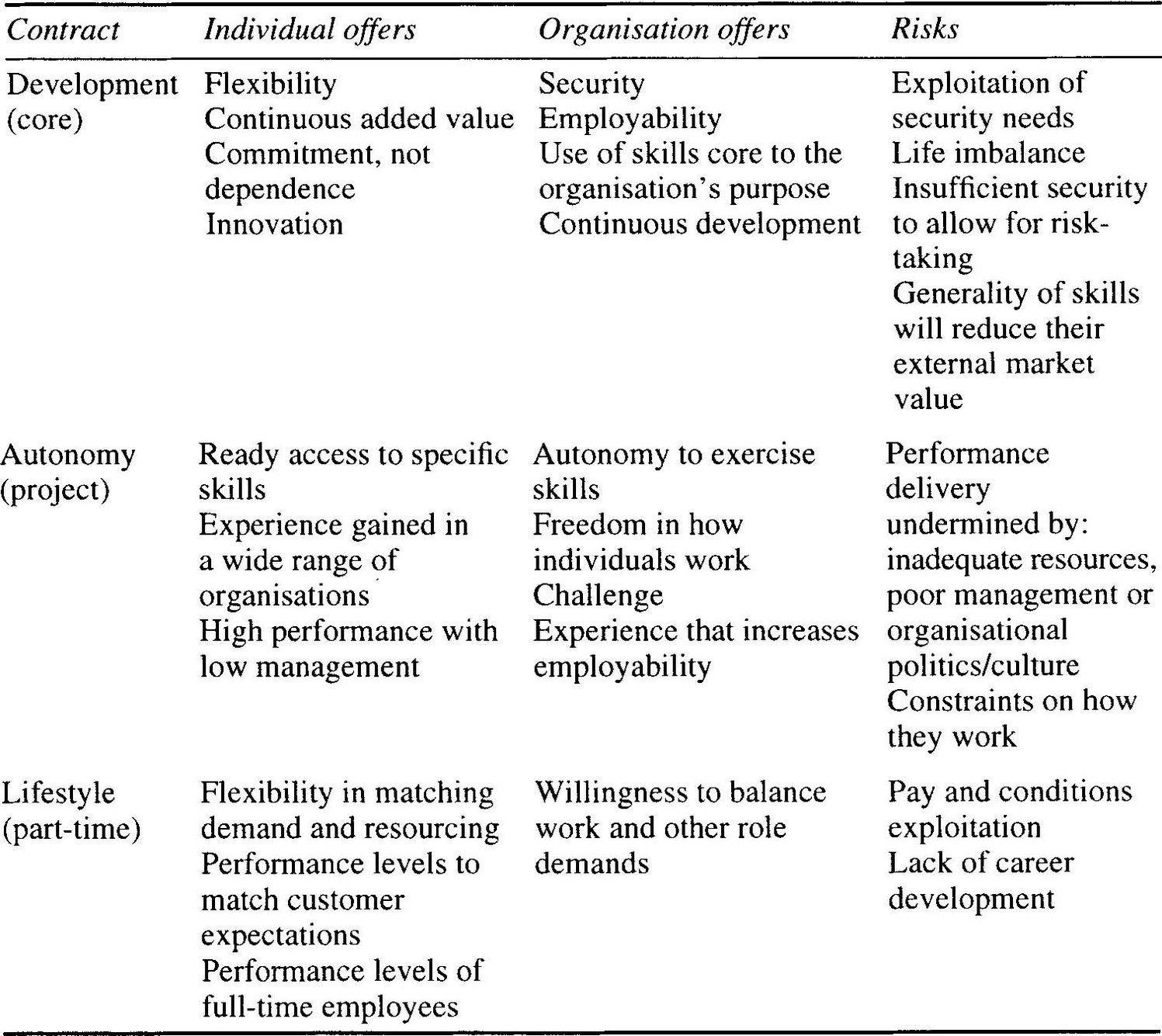

Middle management has attracted considerable attention in this context because it has been perceived as hardest hit by company downsizing and delayering exercises. A research study in the UK found that in spite of recent events, most middle managers still felt a sense of commitment to their employers. What they want is more variety at work, more responsibility, and the resources to help them meet these new demands. Looking ahead, the study concluded that the changing balance of core and peripheral workers currently taking place will influence both legal and psychological employment contracts. A new model of employment relationships has been proposed by Peter Herriott to cater for the three emerging types of employment relationships, one that will satisfy both organisational and individual needs, as illustrated in Table 2.1.8

Table 2.1 New model of employment relationships

Source: Herriott and Pemberton, A new deal for middle managers

Evidence from the USA also indicates some deterioration in psychological contracts.9 This has led to exhortations to employees to build their own identities and careers instead of subordinating their needs to the corporation, and to employers to take responsibility for helping their workers to maintain employability.10 In this vein, Rosabeth Moss Kanter11 supports a model company employment statement that promises to:

• recruit for the potential to increase in competence, not simply for narrow skills to fill today’s slots;

• offer ample learning opportunities, from formal training to lunchtime seminars – the equivalent of one month per year;

• provide challenging jobs and rotating assignments that allow growth in skills even without promotion to better jobs;

• measure performance beyond accounting numbers and share the data to allow learning by doing and continuous improvement;

• retrain employees as soon as jobs become obsolete;

• recognise individual and team achievements, thereby building external reputations and offering tangible indicators of value;

• provide three-month educational sabbaticals or external internships every five years;

• find job opportunities through the network of suppliers, customers, and venture partners;

• tap our people’s ideas to develop innovations that lower costs, serve customers, and create markets — the best foundation for business growth and continuing employment.

2.7 Retention

Positive staff retention policies, if they are to be effective, must be based on measurement and analysis. Staff wastage can be measured in a number of ways, making use of information from the HR records database. The most commonly used measure is crude labour turnover on an annualised basis: the number of employees who have left in a calendar year, expressed as a percentage of the average number of employees during that year, as shown below:

Staff turnover of clerical officers employed in a local authority

Average number employed during the year= 1000

Number who left employment during the year= 100

Turnover is

This turnover figure can and should be calculated for departments and skill groups as well as for the organisation as a whole. Where considerable variations between departments are revealed, there needs to be a follow-up study to find out why some departments are showing relatively higher figures. High turnover is frequently an indication of low morale, poor supervision, unsatisfying work, or poor working conditions. However, this statistic can be misleading unless a stability figure is calculated at the same time. This is because it provides no indication as to whether a range of jobs in a department are experiencing turnover, or only a few jobs. Thus in the illustration provided above, the 100 leavers might have all been in the same job, lasting only a day or two before departing, or in 100 different jobs. A stability index is calculated by expressing the number of employees in a department or job category with more than twelve months’ service as a percentage of the average number employed:

Stability of clerical officers employed in a local authority

Average number employed during the year= 1000

Number with one or more years’ service= 950

Stability is 950/1000 = 95%

Taken together, in this case these two statistics show that turnover is only a problem in a few of the clerical posts in the example. But for human resource planning purposes more than one year’s figures are required to establish a trend and provide confidence in predictions of what might happen over the next one to three years. Contextual data also need to be collected, such as levels of unemployment and relative pay rates.12 The likely impact of labour wastage on the stock of manpower over the next few years can then be used to predict the numbers likely to remain voluntarily in post. It can also be used as an input into more sophisticated modelling of the flows of manpower between grades. This can be of assistance in calculating likely promotion rates, and for career planning purposes. Computer-based mathematical models assist this process. Most models assume a traditional hierarchical graded organisation structure to predict flows into and out of grades within an organisation, as illustrated in Figure 2.3.

Figure 2.3 Model of manpower flows in a traditional organisation structure

Recent years have seen a shift away from hierarchical structures with a large number of levels to organisations based on smaller operating units with few layers, as already outlined in the previous chapter. This trend to simpler structures with lean staffing levels makes the need for planning even more important but turns the emphasis from quantitative to qualitative changes in the workforce. Forecasts are needed for both the numbers likely to remain in employment, and whether staff will possess the attitudes and skills that a changing environment will demand. Because of this, many organisations now place emphasis on multi-skilling and flexibility, enabling employees to tackle a range of tasks and to respond flexibly to as yet unforeseen demands from customers or their public masters.

2.8 Measuring absenteeism

Human resource management is concerned with achieving and retaining a committed and productive labour force, and high levels of absenteeism, like wastage, indicate a failure to achieve these goals. Additionally, human resource planning requires forecasts of attendance as well as wastage, and measures of absenteeism over a number of years are needed in order to measure trends and to make sensible forecasts.

Three measures of absenteeism are useful — percentage of lost working days, days lost per working year and average length of absence. Percentage of lost working days is calculated by expressing the number of days actually lost as a percentage of the number of days which should have been worked in a year. The most frequently used formula is:

Some organisations prefer to simply state the number of working days lost in a year per category of employee. The third measure is achieved by dividing the number of days lost by the number of absences to calculate the average length of each absence.13

An example of the first measure, expressed as a national problem, is provided by an Industrial Society survey which showed the national UK sickness absence rate running at 3.97 per cent, with absence rates in the public sector of 4.57 per cent, compared with 3.87 per cent in the private sector.14 The same report estimated that workers in the UK take 200 million days off on sick leave each year at a total cost of £9 billion. Evidence from the Health and Safety Commission shows sick absence costing Britain £25 billion a year.15 Days lost through sickness varies considerably by industry. Transport workers on average lose 20 days a year, manual workers in London boroughs 19.3 days a year, coal miners 9 days a year, shop workers 7 days a year, and financial services staff 5 days a year, with a national average of 7 days a year. The OECD (Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development) has reported that Britain had the worst absenteeism in the industrialised world, losing 113 million working hours each year compared, for example, with France’s 51 million. The Labour Force Survey conducted by the Office of National Statistics in 1995 showed 275 000 public sector workers, 4.5 per cent of the 5 959 000 total, absent from work for at least one day in a particular week singled out for measurement that summer. This figure was 50 per cent greater than the comparable figure in the private sector. Sick leave in the Civil Service totalled 3.6 million working days in 1994.

Measurement reveals the size of the problem. Yet it is a problem which many organisations do not take seriously, to their cost. It may be that because most absenteeism is put down to sickness, there is a feeling that little can be done. However, this is not the case. Some organisations achieve far better absenteeism levels than others.

2.9 Controlling absenteeism and wastage

Absenteeism and labour wastage represent a decision by the employee not to turn up for work. If reasons can be found why employees are not turning up for work or are quitting their jobs, a search for solutions can commence.

Some non-attendance is involuntary. Employees may be genuinely too ill to come to work or may have suffered a major domestic crisis. Therefore there is a basic minimum level below which it is unreasonable to expect non-attendance to fall. As noted, the national average for sickness-related absenteeism is 7 days a year. Some organisations achieve considerably lower figures. Research and common sense both point to a number of factors which influence non-attendance. These include penalties for non-attendance, the expectation that non-attendance is being closely monitored, the commitment of employees to the work they are doing, the degree of job satisfaction achieved at work, and relationships with fellow workers and bosses. A list of relevant factors provided in a model devised by Steers and Rhodes in 1978, and still relevant today, is shown in Figure 2.4.16

Figure 2.4 Factors influencing attendance and absenteeism

Source: Steers, Rhodes, Major influences on employee attendance

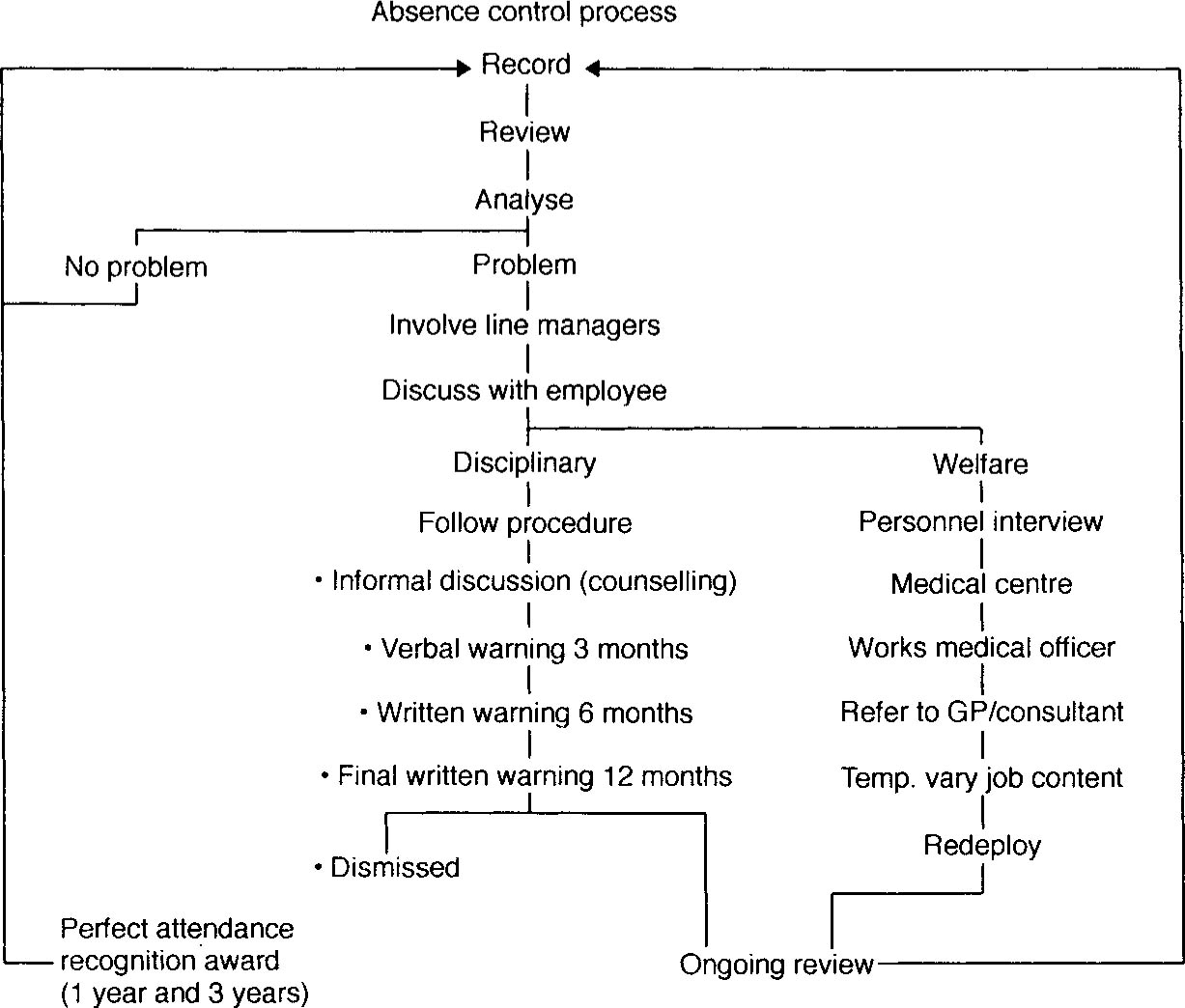

If measurement indicates that there is a problem, the first stage is to locate where it exists, i.e. in which departments, or categories of employee. The second stage is to try to find out the cause or causes of the problem by interviews with staff and supervisors and use of questionnaires. Steps to tackle the problem can then be initiated, and followed up to see if they are working. An example of a successful scheme, which had the desired effect of reducing absenteeism to a satisfactory level, is provided in Figure 2.5.

Figure 2.5 Example of company absence control procedure

Controlling labour wastage requires a similar approach, namely, measurement, location of the problem, finding the reasons, implementing measures, and reviewing progress. The most significant difference, however, lies in the difficulties in establishing why people are leaving. When people give in their notice it is important that they should be interviewed by their head of department, and in some cases, by an HR executive. They may also be asked to state their reason for leaving in writing or by ticking the reason on a short-list of possible reasons. However, the fact is that leavers are frequently reluctant to tell the truth, the whole truth, and nothing but the truth about their reasons for leaving. They may not wish to upset people, or may be afraid to tell the truth, or not wish to jeopardise the reference they may need from their employer. Following up staff after they have left usually results in a very poor response. There is no easy solution to this problem, although a trained interviewer can usually get somewhere near the truth.

A more positive way of tackling labour wastage is to focus on why people stay, rather than why they leave. As the overriding objective is to achieve high levels of productivity and motivation, it is important to find out why staff stay, and what they find good about the job, as well as their criticisms. Regular attitude surveys are of great assistance and enable management to deal not only with complaints, but more importantly, to enhance the positive aspects of employment packages.

Improved retention is achieved by paying attention to the factors that enhance employment, both financial and psychological. Unfortunately evidence is building up that levels of job satisfaction in the UK have declined over the past 20 years. A large-scale survey by International Survey Research (ISR) showed only 53 per cent of British workers responding favourably to questions on terms and conditions of employment in 1995, compared with 64 per cent in 1975. Employee satisfaction with pay and benefits had deteriorated over the last ten years by 14 per cent, with colleagues and managers by 15 per cent, and with opportunities for personal and career development by 17 per cent. The survey covered 17 European countries, and showed the British as second only to the Hungarians in their overall level of job dissatisfaction.17 There is clearly a lot more to be done to improve job satisfaction and employee retention in the UK.

2.10 References

1. Olins R. Polishing up the image in the skills crisis. Sunday Times 5 November 1989.

2. Industrial Society Press. Blueprint for success: a report on involving employees in Britain. London: May, 1989.

3. Social trends. London: HMSO, 1996.

4. Wheeler D. How to recruit a recruitment agency. Personnel Management April 1988.

5. Arkin A. Sold on interest. People Management Review 1996; 13 June: 9–13.

6. Rousseau DM. Psychological and implied contracts in organizations. Employee Rights and Responsibilities Journal 1989; 2: 121–139.

7. Robinson SL, Kraatz MS, Rousseau DM. Changing obligations and the psychological contract: a longitudinal study. Academy of Management Journal 1994; 37(1): 137–152.

8. Herriot P, Pemberton C. A new deal for middle managers. People Management 1995; 15 June: 32–34.

9. Robinson et al., Changing obligations.

10. Heckscher C. White collar blues: management loyalties in an age of corporate restructuring. New York: Basic Books, 1995.

11. Kanter RM. Creating a habitat for the migrant manager. Personnel Management 1992; October: 38–40.

12. Bevan S. The management of labour turnover. IMS Report no. 137, Brighton: Institute of Manpower Studies, 1987.

13. IDS Study Controlling absence. Study 498, London: Incomes Data Services, January 1992.

14. Industrial Society. Wish you were here. London: March 1993.

15. Thomson A. Unhealthy trends in Britain’s sick leave. The Times 12 June 1991.

16. Steers RM, Rhodes SR. Major influences on employee attendance: a process model. Journal of Applied Psychology 1978; August: 393.

17. Whitfield M. Britain grapples with changing job market. People Management 1996; December: 10–11.