Making Money

You should now have your head around some of the key theories and principles about how players buy content and how as designers we need to think in order to engage users and keep them paying. In this penultimate chapter we are going to take a look the practical reality of what we will actually do to make money. To do this we will take a look at the various potential sources of revenue and how we can present those elements to give us the best chance to build the widest possible paying audience as well as maintaining high lifetime values.

Brought To You by Our Sponsors

Let’s start with advertising. This is often one of the first revenue mechanisms considered by developers when they think about a “free” game. It’s a formula that has been used to deliver content “free at the point of consumption” and has historically been synonymous with radio and television1 programming. It’s also something that has been widely used to generate revenue for web and mobile developers; but with games this has sometime caused problems in terms of the reaction of the user, usually when the adverts unduly interrupt the player experience. Despite that, the advantage of being able to gain some revenue without having players themselves make the purchase decision is significant. This is an approach that really rewards scale and where players contribute simply by coming back and playing.

Paid, Cross-Promotion and Incentivized

There already exists a healthy ecosystem for advertising in apps, particularly games with several companies specializing with different approaches and tools. Indeed, I would argue that games are one of the most effective markets for advertising. Where else can you advertise within your competitors’ product (where your target audience will be) without negatively impacting their performance? The most obvious approach in advertising is the classic “paid” adverts, which are pretty straightforward, with costs charged off a rate card or auctioned off using a calculation based on either useful views (effective CPM2) or response (CPA3). As well as classical paid ads there are cross-promotion networks such as Chartboost, Appflood and Applifier’s Facebook service, which introduced the concept. These often combine the traditional paid approaches, often using some form of bidding system, allowing the developer to buy installs at a better price, but perhaps from less effective games (from a conversion perspective). What makes a cross-promotion network different from paid ads is the opportunity to offer an “install swap” mechanism, creating an exchangeable currency from each install your game delivers for other games in the network. Importantly, this means you can bank the value of your installs helping the discovery process for your later releases, even your new products.

Then there are incentivized download services, such as TapJoy. While these have been barred from iOS apps, there can be good value gained on other platforms by using some form of incentive to encourage the player to act, often using in-game currency. This becomes particularly clear if both games share the same virtual currency. However, adding any incentive will change the dynamics with the potential for unintended consequences; for example, if you pay only on install this can create a wave of players only interested in getting the virtual cash and never playing the game.

Getting On With It

Choosing the right partners requires you consider a wide combination of factors. First there is the relationship with that partner, not always an overriding factor but if there is a level of trust then this can help with problems as they arise. Next we have to consider the simplicity of the integration process. There is always an API involved and you never know when this will conflict with another API you are already using; testing and implementing always have a cost implication. You need to know what revenue you can expect from each impression or install and what their fill-rate will be; in other words how effectively they use your inventory (that’s the number of places in the games where you can place an ad). There are mediation services out there that can help you access multiple ad networks with just one integration, but you do need to be careful how much they impact your end revenue for the game. It’s especially important to understand how the ad revenue for your game is calculated by those networks. It’s often done on a different basis than the way it is sold—for example, you might buy on a cost per install and sell on eCPM—this approach gives the ad platform some wiggle-room for their profit.

Implementing the API is usually the easy part, apart from the regression testing. The complication comes in how you decide where in the game you are going to place the adverts and whether these will be links, banners, interstitials, still images, animations, or even full videos. The placement and timing of adverts is crucial. Despite the temptation, try to avoid putting adverts in the way of the flow of play for the freeloading players. Advertising might seem to be the only revenue we get from them but without them we don’t get the ‘Network’ value that encourages other players to discover and spend money. We can’t afford to lose them so we can’t just shove an advert in their way at every possible point. This wears away at their willingness to continue to return to the game. We want non-paying users to think that our game is valuable enough to justify the advertising and that without it they wouldn’t have the free experience they enjoy.

Keeping the Flow

When placing the ads, look for points in the game that naturally work alongside the state of the player—such as loading screens or just before returning to the menu screen—and make the ads easily skipped. Measurement of the player response here is really important. Test and confirm that your placement of an ad supports the longevity of a player as well as working out whether it helps gain an increase of revenue. Also consider the use of “opt-in” advertising, such as GameAds from Applifer 4, where the player accepts the “burden” of watching an advert in order to obtain some in-game currency. This makes the “free” currency more valued as the player understand that it helped generate some income for the game and at the same time it required some effort on their part to obtain, even if that was just to watch a fun clip of another game. At worst this will help extend that player’s engagement with the game and may just show them the value of spending money directly helping convert them to become paying users.

Is Advertising Up To Standard?

Advertising has its place but, at least at the time of writing, the vast majority of advertisers were either other games or they related to gambling services. This means that there is a lot of recycled cash passing through the system, i.e., where I spend the advertising revenue I earned in my game on advertising that game in other games. I suspect this will change rapidly as mainstream consumer brands start to see the potential audience size within games, which already has overtaken anything offered within the TV industry. Brands like Red Bull and Audi have a reputation for being willing to experiment, but for other brands to embrace the opportunity within games we have to demonstrate reach, frequency, and repeatability. Reach4 means the size of addressable audience among the target demographic the brand is interested in. Importantly this is about the potential audience size offered by the medium, not the actual numbers of people who will be exposed to the commercial messages in reality. Frequency refers to the number of occasions the user will be exposed to that advert. This is a key factor that influences the effectiveness of the advert, alongside the message, format, and creative quality. Repeatability, on the other hand, refers to the advertiser’s needs to be able to take the same promotional material and use that unchanged across lots of different providers; it’s about packaging the advertising material so that it can be leveraged across as wide a range of channels as possible. Outdoor billboard posters all conform to a set of standard sizes ranging from the Adshel (1800×1200cm) to the 96 Sheets (12000×3000cm).5 It’s this last part that we have yet to really work out, from the perspective of the bigger brands. They expect to some predictability of where their advert will appear, how frequently, and to know that the experience will be suitable for their art style. If we are going to reach out to brands on a more consistent basis, we have to find easier ways to ensure they can create consistently repeatable experiences across multiple applications.

What Measure Success

It’s hard to find good data, to judge success in advertising for games; anecdotally the cost of acquisition can be up to $6, but the best reliable source I can find is Fiksu’s cost per loyal user6 which in July 2013 reached $1.80. This is a milestone in that mobile acquisition costs now have reached the same heights as Facebook games did prior to the downturn in social games.

From personal experience, largely taken from data based on social games from Papaya Mobile, is that I would expect 24 percent of total revenue to come from the contribution from advertising. However, this seems to vary widely. Some developers, notably Rovio and Kiloo, once their audience reaches a daily critical mass advertising of multiple million daily active users, can achieve the necessary reach to generate very significant revenues. Without this critical mass, ad revenues can be disappointing. Rovio went further than this by creating their own media channel with their own weekly Angry Birds animated series embedded into the games. They are now working with Disney and, if successful, they are likely to change the way many people consume this kind of content.

Virtual Goods

The sale of in-game items is critical to the success of a game as a service; to be able to make this work we have to be able to separate which part of the game is central to the experience and which generates a sustainable audience from aspects of the game that are added-value propositions that can be sold to that audience. The term “added-value” is essential. We are not trying to remove the reasons to keep playing, but we do need to create value that encourages players to get ever more deeply engaged.

We also want to find ways to be make our game scalable in term of efficient production. That means we need to find things that are easy to duplicate or encourage repeated use of the rest of the game, rather than having to incur large costs to sustain the experience.

For example, if we take the time to hand-make something beautiful in the game, we want to make sure that it is going to be used by as many people as possible. Similarly, we want to sell things as efficiently as possible, the posting of a new database entry that counts how many health potions you have is incredibly cost-effective and has a clear value-add to the player.

But What Do We Sell?

In order to work out the right products to monetize we need to go back to what we talked about in Chapter 3 and start with the mechanic. In that chapter we talked about the importance of challenge, which is essential to the fun of any game, and the conditions that can improve the flow of the play. The challenge might come in the form of how much damage you have do, how fast or accurately you have to drive, or even the ability to think enough steps ahead to place an item correctly. Using this knowledge we need to isolate items where we can adjust those elements, ideally through the soft variables that change the strategy rather that the “win/lose” conditions as we discussed when we talked about uncertainty in Chapter 7.

To put this in more practical terms, let’s take the example of a first-person shooter where we might consider of alternative weapons or upgrades that deliver the same damage (leaving the difficulty unchanged) but with different combinations of accuracy, power, or frequency of shot; playing into the preferences of the user. In a driving game we might adjust the components of the vehicle from tires to suspension, even the exhaust, and adjust the car’s performance within a range of ability. This kind of thinking applies to any game and helps you identify any number of different potential virtual goods. Anything might make a suitable candidate for goods to sell—from in-game currency, energy crystals, ammo, different weapon choices, different vehicles, power-ups that clear matched lines of gems, new levels, etc. We then have to think about how selling those items will affect the overall experience and what value they will add to the player from their perspective. To do this requires us to apply the concepts of the buyer behavior we talked about in Chapter 13 to these goods. Will creating alternative weapons (and their associated strategy) add to the joy of playing the game or simply create a mechanism to guarantee winning by spending? Will adding a new level be an efficient way to increase revenue or might it be more effective to increase retention? If we use a fuel mechanic, will the “friction” we add to the game to make this work increase players’ engagement due to the impact of notifications to return back to the game later? At the same time we have to ask ourselves that most important question, “so what?” Why should the player care about this new virtual good, in what way does it solve a need for them, and how does it make the game better?

Sometimes We Have To Say No

Not every game has mechanics that easily support monetization without causing too some kind of a negative reaction among the players. However, it is always a useful exercise to think about the role of each variable in the game and how we might be able to convert them to a revenue model, even if it’s uncomfortable. The deliberate choice to not use a potential monetization method, to preserve the integrity of the playing experience, is as important as the need to avoid missing new ways we might trigger a purchase, generating added value to the player.

Monetizing Context

Once we have assessed the mechanics, we need to look at the context of the game and, once again, isolate potential elements that can sustain the experience longer. This will consider elements that help define out progression within the game, whether that’s about the journey a player goes through or the narrative of the story. Often this means looking at those items that multiply the rewards we obtain for our efforts, so that we can buy a bigger, better-looking car or farm. Sometimes this will include the ability to purchase unique vanity or narrative elements, provided they contribute to the telling of our own story or provide a means of comparison with others, e.g., I completed the “Kobayashi Maru.”7 Once again we have to consider the consequences of charging for these items and determine if doing so will increase the enjoyment and retention of the game. Selling a larger storage area for your player to put their collectable items is a classic example that affects the state between gameplay sessions. However, the idea of restricted use doesn’t have to be limited to storage, it could be a slot for a weapon you use in combat, a maximum capacity for your in-game currency or the area you have available to farm your crops. We can go further and apply emotional values to these goods, even use them to help customize our experience. This about the effect of an option to spend money to access my own Constellation Class starship in Star Trek Online; for me, as a moderate Trekkie, this was irresistible. Finding the ideal retail items within our game, whether at the mechanic level or at the context level, is fundamentally a question of game design. The only difference is that we have to again ask the question “so what?” from a user perspective if we want to know that this will be a viable product to sell.

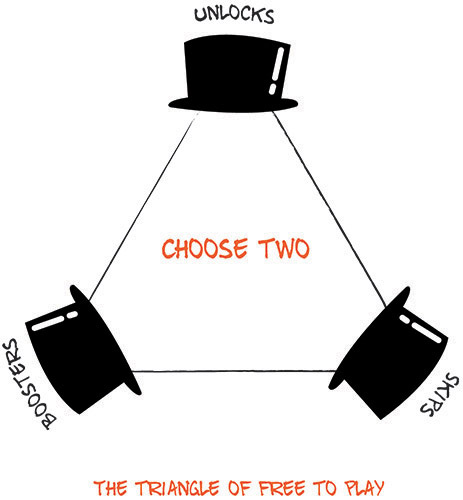

Given Three Options—Pick Two

There are some general principles that help us ask the right questions about the implications of specific virtual goods. Tadhg Kelly8 in his blog, What Games Are, talks about the Freemium Triangle as an attempt to resolve the dangers of accidently creating a “pay to win” scenario where players could in effect buy away any challenge. The idea is that if you assume that monetization comes down to boosters (temporary enhancements such as a special weapon with limited shots or a token that turn the red gems blue), unlocks (permanent access to a feature like a new car or larger farm) or skips (such as fuel to unlock an energy restriction, healing potions, and the ability to skip a cool-down period), then you decide that you can offer any combination of two of these elements, but not all three. This way you can isolate at least one of the core dimensions of game design from being beaten simply by spending cash. This leaves the designer a safety net and means that their game will continue to follow the principle that the shared rules of play should be fair.

Figure 14.1 The Triangle of Free to Play.

Does Fairness Matter?

There are other designers who don’t believe this is necessary. At one of the GDC 2012 Roundtables there was a discussion on F2P design where the consensus was that “the only people worried about Fairness in Free2Play games have never done it.” It’s hard to take a comment like that out of the context (as I have just done) and still do it justice. What I think they are saying is that much of the concern over game balance that is expressed when it comes to F2P is a distraction, a straw man argument made out of fear. On the other hand in late 2013 there was a counter reaction against the idea of ‘Pay to Win’ suggesting goods should have no effect on play. For me the trouble is that Designers (and Players) aren’t experienced enough with F2P design to know the right strategy. Whatever design strategy we take with monetization we should do this thoughtfully and with that in mind I believe that Tadhg’s Triangle remains a useful way of thinking, especially when you are first experimenting with freemium. We shouldn’t ignore the consequences and affects our decisions over monetization models will have on our playing experience.

Monetizing Metagames

As well as looking at the mechanics of play or the game’s context for inspiration, for opportunities to create virtual goods we can also look at the metagame. Here we need to consider all of the characteristics that encompass the role of the game in our life from the physical space around the game, the social interactions, and, of course, any higher-level self-actualizing gameplay. There are some games that can realistically benefit from monetization only in the metagame, or at least where the real revenue opportunity only happens in this higher perspective. For example, Clash of Clans comes alive in terms of monetization only really when the player unlocks the clan system and the group collective combat system. This social experience drives an almost “pyramid-scheme” quality, but in a good way and without the criminal negativity implicit with a Ponzi scheme. What I mean by that is that the engagement with the player is extended by the other players they interact with. The sense of community and belonging to the clan is only enhanced by the shared wins and losses as well as the commitment to the challenge. Of course you will invest more in the game if the “survival of your clan” depends upon it.

Review Your Candidates

Once this review process is completed and we have worked out the best candidate goods for our game and how they impact the flow of play we need to consider exactly how they are going to be bought.

Consumables

Many of these items will be consumable, limited-use items that grant a temporary bonus or ability, such as higher power ammo. They should also tend to either have a measurable but still limited effect on performance or, better yet, influence the softer variables; how we play rather than whether we win or not. Other goods might focus on increasing the results of our actions, such as a coin doubler or experience point boost, which are only valuable once the specific play session has concluded. Some of the items might even be specifically to protect against negative things happening, such as an insurance policy against your plants withering. All of these contribute to play in some way and should be easy things to appreciate and value. However, once they are used they are gone (until you buy more of course).

When looking at a consumable good we have to think of them in one of three conditions. First, what is their role as a “gateway good,” is their value obvious and immediate? Second, why would you continue to spend money on them over time, particularly later in the playing experience? In other words, will players find the ongoing need for an endless supply of these items still appealing at the later life stages, or will these become a “nagging” influence? Finally, we need to consider how players will respond to purchasing them at “hot” moments. For example if we offer a health potion at the point of the player dying (allowing them to continue), will that enhance the playing experience or simply feel like we are being manipulative? The reality is of course that it depends. Offering goods at the point of need is a good thing provided that the design of the user flow is focused on the player’s entertainment. For example, as well as offering that last minute top-up, we can also reward players for thinking ahead, storing potions they discover through play as well as offering a bundle or discount if they buy health potions in advance. Paying close attention to these kinds of details will pay dividends. Better yet we should think how the gameplay can be enhanced through the choice we offer the players through of the goods available.

Balance In All Things

Consumable goods are not the only way to sell items in the game, but they can be effective provided they deliver delight and some opportunity advantage to the player when using them. We should also be fairly generous about how we make them available to players free of charge, not just at the beginning of play; perhaps not as much as a player might want to use but enough that they don’t resent the game for withholding access to them. We want to build a level of comfort and familiarity among our players for the goods we have on offer, while still giving the player a reason to want more of them. If they really add value to play, rather than just being a tax on poor playing, then there is good reason that players will actively want to purchase more. It’s a very fine line between being generous and removing the need for buying them at all or the whole idea becoming seen as a source of nagging for money.

BOGOF Retailing

As we have already said, we are the retailers now, and as such we can use the techniques any local shop might employ to encourage players to spend more with us. Why not sell a bundle of our consumable goods? Buy one get one free (BOGOF), a pack of 12 for the price of six, and other volume discounts all become useful ways to increase the perceived value and which in reality have no practical costs for us to deliver the extra items, except regarding the opportunity costs of that player making a subsequent purchase. These items are consumable of course and the whole point of them is that the player will want to use them up in order to gain the benefit. There are risks of course including the need to avoid misbalancing the game if we give away too many consumables. However, the biggest issue with consumables is that they generally don’t increase the players’ investment in the game. Once they are used, that gameplay benefit is realized and I have to buy another to get the benefit again. There is no ongoing utility being built up inside the game.

One of the things that has surprised me with games like Candy Crush Saga from King is why they only offer you one “save me” power-up for 69p when you get to the end of a level without meeting the success criteria. If they offered a bundle of five, perhaps even ten, at that point then the player would not just get better value, they would be helped through their current level and still have a number of additional power-ups that can only be spent by playing the game more. Perhaps they tested this and it didn’t return the same revenue potential, who knows? However, these are the kinds of things that are worth testing for your game.

Something More Durable

That takes us onto the durable goods where players make a (generally larger) payment into our game to get access to an item that generates an ongoing aspect of the game. That’s different from permanent goods such as special weapons or one-time upgrades of the player’s tools, equipment, or other abilities to play the game. These one-off purchases do have an ongoing consequence, but I would argue that these rarely add ongoing utility into the game. They don’t create deeper reasons to return to the game. Permanents can be great sellers and some game genres, including tower defense games such as Fieldrunners, reportedly get the majority of their virtual goods revenues from them. They can also provide a touch of glamour to a game. The appeal of buying a +5 Vorpal Blade is much greater than buying five +1 Damage Crystals. Permanent items are aspirational, but once obtained become part of the default setting of your game.

A Well of Crystals

Instead I want you to consider durables goods that you buy once, but that expand the choices of play or stimulate the player to return to the game in order to maximize their benefit. My favorite example is the Well of Energy Crystals.9 This is a one-time purchase that generates the usually purchased energy crystals that grant me fuel to do more in the game and I will probably have already been buying them as a consumable. The Well might cost of about the same as buying ten individual energy crystals, but delivers ten crystals over 24 hours if you come in to collect them. This kind of virtual good delivers real utility into the game for the player and doesn’t inhibit the player buying another extra energy crystal should they feel excited enough to do just that one extra task that day. Indeed, it gives players permission to feel more relaxed about buying the odd energy crystal because the knowledge that they are going to get more tomorrow anyway makes it their choice to spend money, rather than having the game overtly influence them to do so.

New Vehicles

Another example would be the purchase of a new vehicle in a driving game or a new spaceship in space exploration game. Designed well, these durable goods introduce new strategies and options that are only possible if the player returns to the game. In Real Racing 3 the player can access specific races based on the cars they have in their inventory and they can race each car separately while their other cars are being repaired. This means that the available time players can intensely engage with the game expands as the player invests further into the game.

The Slot Machine

Durable goods can influence game progression in other ways to reflect the progress of the player in the game’s context as well. Imagine that you have a hover vehicle with three power-up slots. The player gets to choose what items to put in those slots—perhaps a weapon or a shield system, an extra life or rocket engine. All of which contribute to their strategy of play. But as a durable good you might be able to purchase a fourth slot. Unlocking a fourth slot doesn’t guarantee that the player will beat the others, although it will influence the outcome.

Collectable Card Games

The use of durable goods to influence strategy choices has long been employed in collectable card games and these in turn are becoming a heavy influence on the monetization design of freemium games. They come in “booster” packs with a random selection of cards. Some of these will have a temporary effect (e.g., mana or land) to be spend to release other more durable cards (e.g., creatures or spells). However, the strategy of their use and influence on the gameplay becomes ambiguous as they are combined. Many mobile games that use this approach allow cards to “improve” by discarding duplicate or unwanted cards, creating a more significant card. Importantly players don’t have to have large decks of cards to play, even to win. However, they will usually have an easier and more interesting time if they collect additional cards. We don’t have to take the metaphor of the cards literally. We could take a racing game and have different brands of engine components that combine together differently to improve the car in unique ways, right down to the details like the number of teeth in the gear ratios, if the audience will respond to that.

Sacrifice

An interesting side effect of the collectable mechanic emerges when you introduce the ability to sacrifice duplicate or unwanted cards in order to enhance other cards we prefer. This creates a way to significantly scale the number of cards any player might need if they wanted to invest to guarantee access to the most exclusive cards. Imagine a basic level 1 Fire Creature Card. We find a duplicate of this specific card and decide to discard that in order to evolve our card into a level 2 Fire Creature Card. In order to obtain a level 3 Fire Creature Card, we have to evolve another pair of specific cards and then discard that resulting level 2 card. As we keep going on this pattern, we start to exponentially increase the number of cards a player needs to guarantee access to the highest level creatures. Combine that with the concept of rarity often used in these games and this becomes very interesting. Cards might come in different levels of rarity—common, uncommon, rare, and super-rare for example. Of course that value will only increase if you have a strong social element allowing players to see each other’s “cards” and to exchange them. The use of the collectable card game model probably deserves its own book because it has subtle depths, yet is infinitely flexible. However, be wary in your use that you don’t try to use it too literally or you risk turning the mechanics of your revenue model into a game in itself. That could easily distract from the game you intended to make. The objectives and mechanics of a collectable card game are as much tied up with the artwork and revelation of the next card as they are with the game itself. That playing model is very much targeted to the collector reward behavior described by Richard Bartle that we referenced in Chapter 2, and unless that was your original intention it can introduce a lucre-ludo-narrative dissonance as we discussed in Chapter 6.

Converting Currency

One of the most powerful tools available for monetization is the in-game currency. These are usually a value generated through the action of play that can then be used to exchange for items within the experience. We talked about this in Chapter 7 when talking about the role of uncertainty generated through imbalanced economies. The term “currency” is largely interchangeable with “resource,” except that a currency is usually available for exchange with any item, where as a resource will have a specific use and, by inference, restricts progression for items within its type. For example, gold might be used commonly in a game to purchase buildings, crops, and equipment, but buildings might also need clay, crops might also need fertilizer, etc. The role of currency in gameplay is also multifaceted. It’s a reward for progress, indeed in some games it is the only relevant measure of our progress. Such games can often devolve late in the player life cycle into an attempt for the player to earn as much currency as possible. Currency can also act as a useful gatekeeper for later stages within a game—you can’t defeat the werewolf unless you can afford the silver-plate armor and sword as well having all the necessary skills. The widespread use of in-game grind currency also gives the freeloading player the sense that they can indeed explore every aspect of the game, they just have to be willing to extend the level of grinding they are willing to do.

Buying currency is possibly the most natural form of consumable purchase. Players already understand what that currency can buy if they have been playing the game and earning money through play. However, if we sell that money then we need to seek other mechanisms, typically other types of resource, in order to sustain the gatekeeping mechanic. It’s vital, as we have already said, that buying currency doesn’t defeat the purpose of playing late in the lifecycle. Resources have similar risks associated with them especially if you allow some level of “exchange” or “conversion” between resource types—something that is usually a good idea from a player’s perspective. However, if you allow this, consider introducing some counterbalance mechanism to prevent another kind of “pay to win” arising by mistake. For example I want to exchange clay for fertilizer. I can do that if I have bought the market building, and then I only get one fertilizer for every two clay and 100 gold I sacrifice. Alternatively allow players to exchange material between them at an exchange rate the players agree, perhaps even take a commission from those transactions using the same resources or the in-game currency. This is often at least as valuable for the social bonds that it helps build between players as it is in terms of stimulating the desire for buying more in-game currency. Another option might be to have a maximum wallet size; the purchase of larger items needing a larger wallet.

Many games introduce a second or third currency, usually specifically a premium currency, such as gems. These can provide a second rhythm of play, in terms of the generation of value through play. Premium currencies can often still be generated through play, but at a significantly slower rate than the standard currency. They are also needed to purchase the higher quality items within the game, the best examples will be for all practical purposes out of the reach of freeloading players. We can also clearly separate items purchased using a premium currency from those available using in-game currency, both offer different aspirational values.

This makes sense as long as their value instills a sense of increased value for that item and an increased desire. However, it can just as be discounted if it seems impossible for a freeloading player to access any of those items. I believe the premium currency approach can usually be better employed if it requires players to make a dilemma choice about how they play. If this slow-burn currency can be used to either sustain the player in their current game or saved for later to exchange for a valuable upgrade, which then matters more to the freeloading player? Of course that means that paying players who spend money don’t have to face that dilemma. This can create a reason to spend, but risks backfiring should this become “pay to win.” To get around this problem we might be tempted to increase the number of different currencies in the game; rarely a good idea as this reduces the value of having a currency at all, so it becomes just another resource. Another alternative is to make it so that players can’t actually buy the premium currency directly. Experience points are an example of premium currency that should never be sold. Instead we can offer goods, consumable or durable, that increase the rate at which we can earn those currencies. The idea of a coin doubler is commonly used, or perhaps an experience point potion (granting a 10 percent XP bonus for the next hour) although to be honest I’ve never liked them myself.

Thinking Differently

Goods need not always be based on positive actions. Often it’s useful to turn existing models “on their head” and consider them from the opposite position. For example, is there a way you could create factors in a game that impair the performance of the player in specific circumstances? For example, introduce wear and tear into a game when the player is using their equipment; imagine I have a sword that is reduced in sharpness—and hence the damage it can do—after 100 combats, perhaps it might even break. I can invest my time and my grind money in repairing this sword, indeed that would make a great minigame, and in doing so I might happen to use up some resources. Perhaps I could pay some NPC in the game (or even another player) to repair it for me?

Infinity Blade on iOS had an amazing model along these lines, which I am surprised I’ve not seen again since. Each item of equipment provided the player with a bonus to their experience, but there was a cap over time on how much extra experience in total they would gain. This forced the player to change to the next weapon that they could afford, etc. This stimulated change, broadened the experience with a range of different weapons, increased the engagement with the game, and stimulated the collecting instinct around those items as well as requiring the player to spend some of their in-game currency. Wow! Just by having swords give you experience boosts!

Turning Off Ads

There is a temptation with developers to offer a way to switch off adverts by paying. This makes sense especially if we feel that the adverts are driving players to leave the game, or if their presence is inhibiting their propensity to spend money. However, I wonder if this option is sometimes used inappropriately. Often the negative reaction to adverts can be attributed to a highly vocal minority and their removal has little positive benefit in practice. I’m not saying we ignore this minority entirely, but instead we should focus on what it is that they find problematic. This might be possible to correct by considering the placement and flow of the advertising you use in the game. Another reason why this concerns me is that only the paying players are likely to purchase the “no-ads” option. These are the very people who potential advertisers want to be able to communicate with, and who make advertising in your game particularly valuable. Giving these users the option to opt-out may well so badly affect the value of the audience to advertisers that the revenue you gain from the “turn-off ads” purchase might not come close to offsetting the advertising income you would otherwise have gained. Don’t give in to an emotional decision, work out whether advertising revenue is important for your game and, if so, make sure its implemented to minimize any negativity from the audience. Getting the best implementation needs to consider the location and timing of display for each ad, the player lifecycle, and the use of “opt-in” methods.

Levels and Episodes

There is another traditionally popular method of revenue generation that I find problematic. The sale of levels is commonly used by platform and puzzle games, as well as in the form of DLC for console games. There is much similarity between level sales and “try before you buy.” They rely on the player being exposed to the game first, getting a familiarity with the experience and then making the decision to purchase the next installment. The trouble is that players are often satisfied with the experience they have just had and don’t have enough anticipation of value from the next installment to make that purchase. The range of players who access each subsequent level will diminish and with it the critical mass of the audience. Further than that, the freeloading players can’t access that material and this further diminishes the perceived value of that content. As we discussed in Chapter 13, selling levels and trials rarely delivers good value as it creates barriers and buyer remorse. It’s also a very inefficient approach, as the levels are usually the part that takes the most effort and skill to create; wouldn’t we rather players get to experience all of the beautiful, expensive to produce, game material we have spent months creating rather than sticking it behind a pay-wall and have no one seeing it? That doesn’t mean that level-based games have no place in a freemium world, but it does mean we need to think very carefully about the best way to monetize them; perhaps using grind currency to unlock each subsequent level. Ian Masters of Plant Pot Games came up a superb metaphor that can help us when we look at making a level-based puzzle game work as F2P. Think of each level as a spinning plate. We have to return to them regularly in order to keep them spinning, so we can set off the next spinning plate/level. The idea of having to regularly return to previous levels in order to gain the points/coins needed to unlock the next game is a powerful one and gives value to ongoing repeat play.

A Mixed Model of Monetization

Every example of different virtual goods or advertising models we have discussed in this chapter will have a role as part of a mixed approach to monetization. Indeed the greater the range of choices and payment methods available to players, the more you will convert to paying at all, just as we discovered with the rent game discussed in Chapter 13.

We have a story to tell our players, not just in terms of the game, but also in terms of the ways they can engage with the game that they love and what works for them will change as their engagement with the game changes. We need to offer predictable opportunities and calls to actions, such as the bundles or last chance “save me” power-ups alongside apparently “random” offers that seem personalized to that players’ needs and likes.

The way goods combine is important and we need to continue to think as retailers and consider opportunities to sell more items to the converted player through the use of “bundles” or collections of related items. This can include: BOGOF deals; a “booster pack” with a selection of random power-ups; special offers on the next vehicle or weapon we would love to get our hands on in the game. Even randomized mystery boxes that grant the player a random item, as used so successfully by Kiloo.

Be Careful with Randomness

We have to be a little careful about how convoluted some of these promotional experiences become, especially where there are random factors. Randomness in terms of what you gain for your money can take us a little too close to gambling for comfort. This became an issue in Japan because of the concept of the “complete gatcha” (kompugacha) mechanism, where sets of random cards/goods are purchased in order to discover rare or ultra rare collectables. Complete sets of these collectables are then used to obtain yet more rare items. The Japanese government announced in August 2012 that they were going to investigate this issue and that caused a drop in the share price for DeNA and GREE.10

A Question of Ethics

It seems almost inevitable that we end this chapter talking about the questions of appropriate use of monetization models. This “complete gatcha” question and others like it continues to ask us to face up to questions of ethical approaches to the monetization of games. Similarly, in the UK, the Office of Fair Trading announced in April 2013 that they would investigate the in-game marketing techniques being used in games aimed at children. Their initial findings, which were announced in September 2013,11 included eight key guidelines. The principles seem relatively straightforward, but there is still concern over how some of them might actually operate in practice, so we expect these will change. They inform developers that they have an obligation to prominently and clearly communicate all material information about the game including the associated costs before it is downloaded. Developers need to be contactable and able to respond to consumer complaints and refunds. Developers should not imply that payment is necessary to continue to play when that isn’t the case, should give equal weight to the non-�payment option, and in particular should not attempt to exploit a child’s inexperience or credulity or directly coerce them. Finally, payments should only be taken when there is informed consent and with the agreement of the account holder. Of course it’s recommended that you consult the documents themselves and perhaps a legal professional to ensure that your games comply.

These findings don’t present an objection to the principle of selling in-game items in particular, they are about ensuring ethical practice in terms of retailing in-app purchases to children to and making sure that there isn’t a reasonable likelihood of “accidently” triggering a purchase on their parent’s card.

Other legal changes have also already come into force in the USA with COPPA (Children’s Online Privacy Protection Act)12 where developers now have a responsibility to identify if the majority of their audience for a game or service are children (under 13) and then manage the capture of data and use of adverting material accordingly. This won’t be the last such law on the subject developers will have to comply with.

There is no excuse for using excessive or aggressive practices in game design. We are making entertainment products and these should focus on the art of engagement, not how much money we generate. To my mind this isn’t a question of ethics; the ethical arguments are often hypothetical, even hysterical, rather than real.13 It’s a practical question about what kind of business we want to create. If we go fishing with dynamite we kill all the fish, if we go fishing with line we only get the fish that are attracted to our line but the lake remains sustainable and we can continue fishing forever. The problem with us constantly arguing over the ethics is that the more we have that debate the more likely it is that someone will come along and ban fishing (not dynamite).

Notes

1 The soap opera format of advertising-funded serial dramas is widely credited to Irna Phillips, an American writer and actor, with Painted Dreams in 1930 on Chicago’s WGN, www.otrcat.com/soap-opera-radio-shows.html.

2 CPM is cost per mille (thousand) views rather than cost per impression; eCPM is a hybrid of cost of impressions and the click through rate (CTR). It allows buyers to gauge the effectiveness of a campaign.

3 CPA is cost per action or acquisition, which usually for games usually refers to the number of installs obtained.

4 Again I need to own up that (at the time of writing) I am working for Applifier and there are other suppliers of opt-in advertising. Reach is a key metric for advertising buyers as they are looking to maximize the potential opportunities for their brands at the lowest cost. The advertising industry has had to evolve with the rise of the internet, but it’s been a long slow progress despite the decline of TV audiences.

5 There are a limited number of standard-sized and shaped-for-billboard advertising that significantly helps advertisers with reach and repeatability, www.clearchannel.co.uk/useful-stuff/billboard-poster-sizes.

6 Fiksu define a loyal user as one who returns at least three times to the app, www.fiksu.com/blog/cost-loyal-user.

7 In case you didn’t already know the Kobayashi Maru is an infamous no-win scenario test at StarFleet Academy in Star Trek, where James T. Kirk was the first person to ever “beat” the scenario by reprogramming the computers (in short he cheated!).

8 Tadgh Kelly, author of What Games Are and at the time of writing Developer Relations for Ouya, www.whatgamesare.com/about.html.

9 Don’t worry, I understand that the use of “energy” has become a little suspect of late, it’s just a convenient example for explanation of the concept. That being said, there remains value in the ideas behind energy, if only because of its ability to create a reason to return when the energy has recovered. I believe this came up in Chapter 5.

10 The founder of GREE and at the time Japan’s youngest billionaire, Yoshikazu Tanaka, lost an estimated $700 million off the value of his shareholding in GREE the day that was announced, www.forbes.com/sites/danielnyegriffiths/2012/05/08/gree-dena-social-gaming.

11 The OFT Report’s initial findings on children’s online games can be found at www.oft.gov.uk/shared_oft/consumer-enforcement/oft1506.pdf.

12 Details of COPPA compliance can be found at www.coppa.org.

13 I’m not saying that there aren’t unethical designers out there. I’m not saying that there aren’t apps that exploit people. I’m just saying that most cases of this argument are being discussed based on hypothetical cases. The real cases should, of course, be prosecuted and the perpetrators handled accordingly; they are damaging our industry beyond measure.

Exercise 14: How Will You Monetize?

In this the final exercise we come to the (potentially multiple) million dollar question: how will you make money from your game? We should now know the flow and structure of our game in detail and as a result of taking the design approach for games as a service it should be a relatively easy task to understand where and how we will use all of the available monetization processes. As we do this we have to be sensitive to the psychological influences on the player’s purchasing decisions including in particular buyer remorse and price elasticity of demand.

We want also need to consider how the attitudes to spending match against the life stages of the player in order to maximize the potential and in particular how we build value or utility into their experience.

We want to know if you will charge an initial fee prior to the download of the game and if so how will you manage the impact on the number of installs this will impede. Then there is the counterargument, if you don’t have an upfront cost then how will you offset the lack of any initial invested utility in the game? We want to understand what virtual goods you plan to incorporate and what combination of consumable (one-time short-term use), durable (ongoing value) or permanent (one-time upgrade) you plan to use.

Worked Example: