CHAPTER OVERVIEW

It's tempting to add exotic or humorous visuals to technical lessons to make them more interesting. This is especially true when designing multimedia self-study courses since high attrition rates suggest the need for extra motivational support. But some approaches to building interest are counterproductive to learning. In this chapter we present research, psychological rationale, and examples to support the following guidelines:

For learners with low personal interest in the training, use techniques to increase cognitive interest in the lesson

Draw on learners' personal interests by using visuals that make the relevance of the instruction obvious

Avoid Las Vegas approaches to learning by minimizing visuals that stimulate emotional interest

Use visuals to make lessons more concrete, familiar, and coherent

The marriage of fun and learning seems like a great idea! Why not capitalize on the seductive appeal of computer games and movies by including similar elements in instructional materials? Las Vegas–style courses that use popular movie and game themes such as Tomb Raider and Jeopardy use an edutainment approach to learning. More subtle Las Vegas approaches use graphics as eye candy to add interest to pages and screens. How effective is edutainment? How can visuals be used to add interest to training materials We address these two issues in this chapter.

Motivation is what prompts a learner to initiate an instructional goal and invest the effort required to complete it. Motivation is the energy that fuels an individual to take a golf lesson or finish a self-study online course. High motivation is especially important in self-study settings where individual commitment is essential. Many reports mention high attrition rates in e-learning courses. For example, Terry (2001) compared attrition between e-learning and comparable classroom courses. He reported e-learning dropouts that ranged from 3 to 43 percent with an average of 21 percent. To counter these dropout tendencies, it is especially important to consider learner motivation when designing online courseware.

One important source of motivation is interest. We know from personal experience that we more readily persist in instructional events—even challenging ones—that are interesting. Research supports the correlation between higher interest and greater learning (Wade, 2001). If you are interested in something you are learning, you will attend carefully and process the information more deeply. Interest leads to greater persistence and use of study techniques that promote deeper learning.

Graphics are one of a number of tools commonly used to engage a student's interest in an otherwise dry lesson. Graphics to add spice to instruction range from entire instructional treatments such as a game theme in online courseware to inclusion of dramatic stories and visuals in books. Figure 9.1 shows a space adventure course theme and is a typical example of a thematic course treatment. Edutainment approaches to instruction assume that if students are enjoying a learning experience, they are also learning. Unfortunately, often well-intended attempts to make materials more interesting can be counterproductive to learning. How can you make your instructional materials more motivating—more interesting—without sacrificing their instructional integrity?

Most training events use a survey response form to measure student satisfaction. Questions typically assess student perceptions about the quality of the instructor, the training materials, and the instructional setting. However, is learning greater from courses that are highly rated than from courses with lower ratings? For example, if the instructor or the materials get high student marks, will the test scores also be high?

Table 9.1. Types of Interest.

Type of Interest | Interest Generated From | Example |

|---|---|---|

Situational: | The graphics placed in instructional materials | Photographs of customers of different ages and racial groups used in customer service training |

Emotional | Visuals that arouse curiosity, humor, or strong feelings | A space-fantasy theme used in computer training to add fun and stimulate learner curiosity |

Cognitive | Visuals that clarify the lesson content | A graphic organizer used to show the relationships among lesson topics in a computer training course |

Personal: | The learner's own predispositions | A soccer graphic used as a visual analogy in a team building course because many of the learners are soccer fans |

Dixon (1990) compared student ratings of a classroom course with the learning outcomes measured on a pre- and posttest. She found no signifi-cant correlations between student ratings of enjoyment and actual learning. Her study suggests that we use caution in assuming that liking will always lead to greater learning.

Designing interesting instructional materials is a natural route to gain positive student ratings. But interesting materials do not universally lead to learning. Research has revealed several sources of interest—some of which are more effective than others at promoting learning. Table 9.1 summarizes the different types of interest to be described next.

Do you devote personal time and energy to developing and perfecting skills associated with a hobby or avocation? We have a colleague who is an avid general aviation pilot. He spends many hours reading technical materials and attending training on diverse topics associated with his flying hobby. His personal interest is the source of his motivation to invest time and effort in learning. Personal interest is a relatively long term predisposition to spend time and energy pursuing and applying specific knowledge and skills. It comes from within the learners. It is personal interest that usually prompts the selection of a college major, for example. However, in many work-related training situations, the learners bring with them varying levels of personal interest in the new knowledge and skills to be taught.

In contrast, situational interest is generated from the learning materials—not the individual. Screens and pages full of technical text are generally rated low in situational interest. One common way to make them more interesting is to add visuals. Instructional professionals have more control over situational interest of the training materials than the personal interests that learners bring with them to training.

As shown in Table 9.1, there are two forms of situational interest—Emotional and Cognitive. As we will see in this chapter, using visuals to enhance emotional interest can depress learning. Instead, cognitive situational interest is a more productive route to enhance both motivation and learning. Cognitive situational interest makes the materials more comprehensible by making them more understandable. In this chapter we will look at guidelines for use of visuals to improve motivation by way of personal and situational cognitive interest.

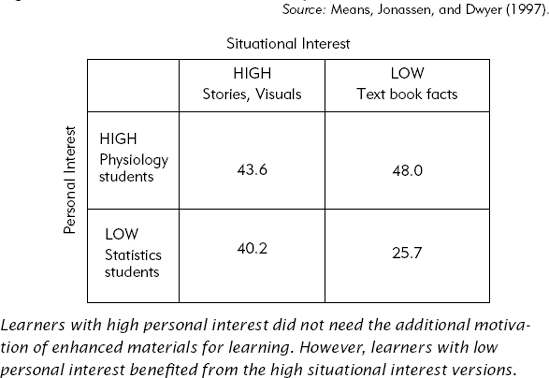

Means, Jonassen, and Dwyer (1997) studied the effects of personal and situational interest to see how they might interact to improve motivation. They developed two versions of a lesson on heart structure and function. One version was low in situational interest. It took a traditional text book approach that simply presented the facts about the heart. A second version was designed to be high in situational interest. It used human interest stories, concrete language, visuals, and analogies. As illustrated in Figure 9.2, these two versions were given to two groups of learners—one group high and one low in personal interest. Learners from a statistics class composed the low personal interest group. High personal interest learners were solicited from a physiology class.

The experiment compared the effects of lesson versions of high and low situational interest on learning of high and low personal interest learners. The results are shown in Figure 9.2. As you can see, the physiology students who had a high personal interest learned effectively from both lesson versions. Personal interest in the heart provided sufficient motivation to override the low interest materials. However, the statistics students, lacking in personal interest, benefited more from the versions that incorporated techniques to increase situational interest. This research suggests that when your learners are likely to lack personal interest, you should invest extra effort and budget to make your instructional materials more interesting. For example, our friend who is interested in aviation will learn even from aviation materials that are not especially interesting. However, someone not interested in airplanes, assigned to training on aviation, would be more motivated to learn from materials with a more engaging design and that use concrete language, visuals, and analogies.

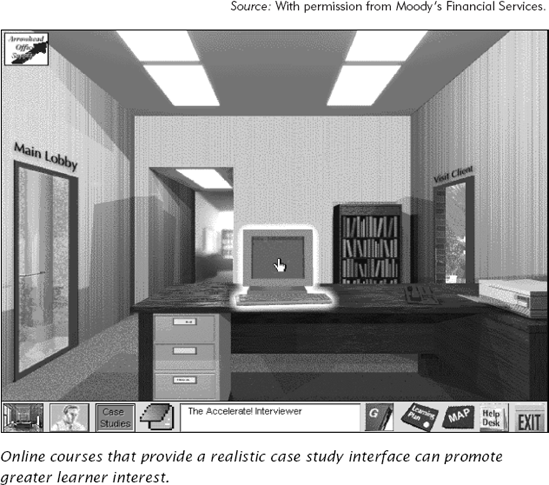

Although the instructor cannot generally control the personal interest of learners directly, she can capitalize on the personal interests they might bring to the training. Training experiences that are explicitly relevant to the job will motivate learners. Guided discovery training architectures that use job-related problems as the source for learning offer one way to appeal to personal interest. Research on problem-centered instruction consistently shows that learners like it better than traditional topic-based training (Vernon and Blake, 1993). For example, in medical education, students who learn basic science knowledge in the context of solving medical case studies such as the one in Figure 9.3 give higher ratings to their courses than students who learn from traditional science classes. That is because when learning is situated in problems clearly relevant to the learners job, personal motivation drives effort and persistence.

Graphics can add relevance by providing an interface that is explicitly job related. Some online guided discovery courses provide a good example. For example, the screen in Figure 9.4 shows an interface used in training on how to evaluate commercial bank loans. The learner is presented with a loan applicant and uses the objects on the screen such as the fax, the telephone, and even coworkers down the hall to research the loan. In this course we see that representational visuals are used to provide a job relevant engaging interface to support learning.

As explained above, situational interest refers to appeal that comes from the instructional materials themselves. However, using emotional interest as a way to stimulate situational interest is counterproductive to learning. In this section we look at emotional interest as a form of situational interest that disrupts psychological learning processes and cognitive interest as a form of situational interest that promotes learning.

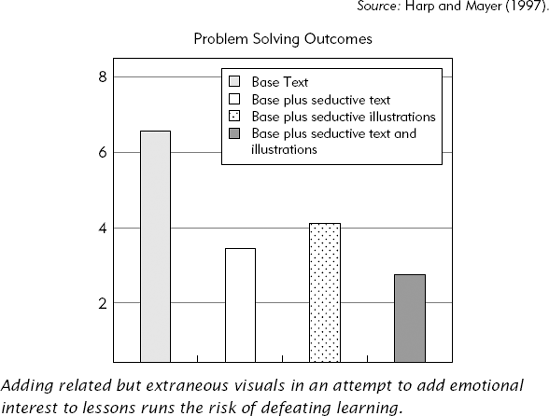

Some materials that are enhanced to add interest actually depress learning. Harp and Mayer (1997) developed four versions of a lesson on lightning formation. The basic version explained the process of lightning formation using text and relevant visuals. An example of the type of visual used in the basic lesson is shown in Figure 9.5. To this basic version, interesting but extraneous text was added that described what happened to airplanes that were struck by lightning or why golfers are at high risk for lightning strikes. A third version added visuals that illustrated the golf and airplane situations. And the fourth version included both the text and visuals similar to the one shown in Figure 9.6 depicting the effect of lightning on airplanes.

As shown in Figure 9.7, learners who received any of the enhanced versions scored considerably lower on a problem-solving test than learners who used the base text lacking extraneous details. Thus we see that adding related but irrelevant visual information to a lesson to spice it up depresses learning. Students may, in fact, remember the sizzle but forget the key concepts. In short, they find the wrapping paper more attractive than the present! As described in Chapter Five, the seductive visuals disrupted psychological learning processes. Specifically they exert a negative effect by activating inappropriate prior knowledge from long-term memory (Harp and Mayer, 1998).

Based on this research we recommend that you manage the sizzle factor of your materials by minimizing words and visuals that are not directly related to the goal of the instruction. Does this mean that you should never use decorative elements in your instruction? Of course not! Our goal is to promote thoughtful use of visuals based on human psychological learning processes. We recommend that you put most of your resources into visuals that promote learning and use decorative elements in ways that do not disrupt learning.

As summarized in Table 9.1, there are two types of situational interest: emotional and cognitive. The lightning lessons with visuals and descriptions of the effect of lightning on airplanes and golfers added emotional situational interest. Figure 9.1 that uses an exotic space adventure theme as an adjunct to technical training is another example of using emotional interest to motivate learning. Any text or visuals added to materials that represent highly unusual occurrences or that represent universally compelling themes such as sex, death, or interpersonal relationships will tend to generate emotional interest. Tabloids with headlines such as 500-pound woman has a 30-pound child accompanied by equally dramatic visuals are prime examples of using emotional appeal to sell.

In contrast, cognitive interest is generated by materials that are easy to understand, familiar, and relevant to the learners goals. We recommend that you use graphics to add cognitive rather than emotional interest to your lessons—especially in situations in which the learners are likely to be lacking personal interest. In concluding their research on the negative effects of emotional interest on learning, Harp and Mayer (1997) recommend that "the best way to help learners enjoy a passage is to help them understand it" (p. 100).

Clark (2003) has summarized research that supports the following techniques shown to increase cognitive interest in training materials:

How can visuals be used to implement some of these techniques?

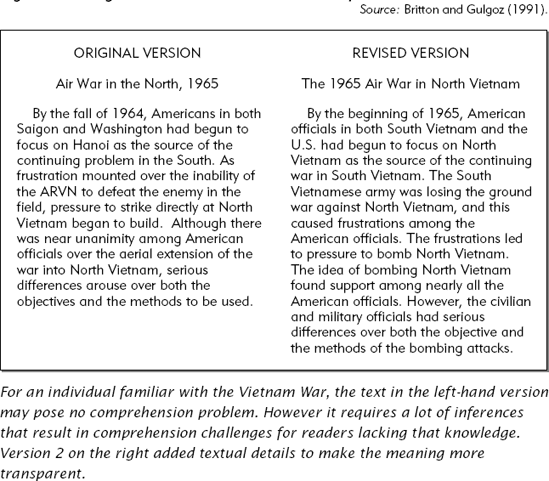

Lesson materials that are understandable and coherent minimize the number of inferences the learner needs to make. For example, read the original version text in the left-hand side of Figure 9.8. To comprehend this text, readers need to fill in a number of gaps. For instance, they need to recognize that North in the title and South in the first sentence refer to Vietnam. They need to associate Hanoi with the North and the ARVN with the South Vietnamese army. For older readers who lived during the Vietnam War, these gaps pose no problem. But for younger readers for whom the Vietnam War is a historical event, understanding this passage could be challenging. Britton and Gulgoz (1991) compared learning from the original and a revised version of this passage shown in the right side of Figure 9.8. Learning was better from the revised version that made the ideas more explicit.

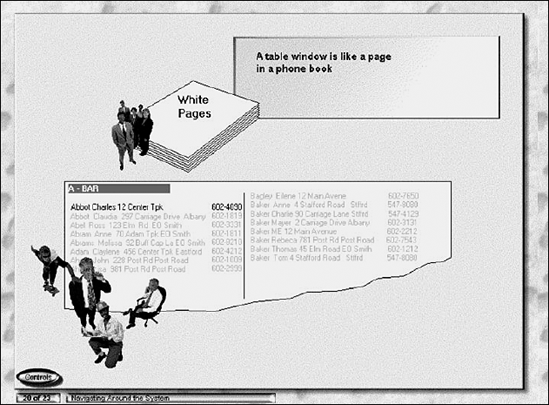

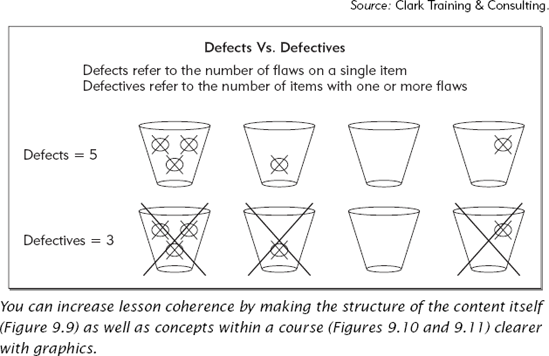

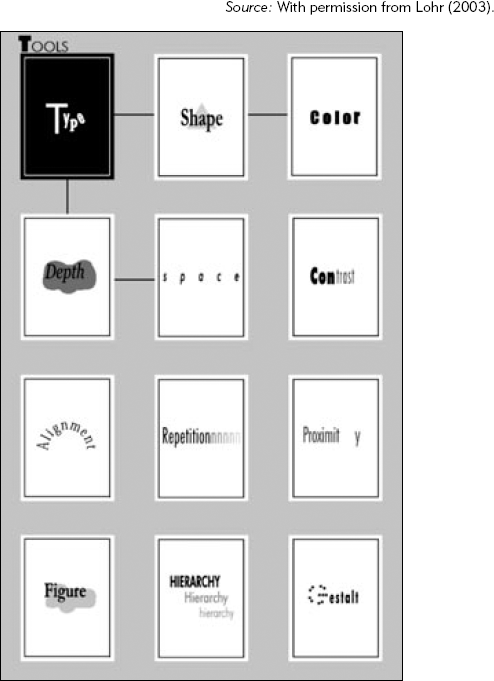

Graphics and Coherence. Although the improved lesson on the Vietnam War used textual revisions to increase coherence, graphics offer an alternative remedy to improve comprehensibility of materials. Use of organizational visuals and visual examples provide two good ways to reduce the number of inferences that learners need to make. Use organizational visuals to make the structure of a lesson more coherent and/or to show relationships among facts and concepts in a lesson. For example, in Figure 9.9 an organizer from a book on graphics includes a visual organizer that states in words that are visual models several graphic design techniques discussed in the book. Figure 9.10 shows a simple graphic that uses a telephone book analogy to explain the structure of a database of customer information. This graphic helps learners build a mental model of what to many users is just programmer black magic.

Figure 9.9. A Graphic Organizer That Uses Visual Techniques to Reinforce the Concept Stated in Words.

Examples are an essential element in the tool kit of all instructional professionals. And examples, especially of abstract concepts, can often make ideas more understandable with the addition of visuals. For example, if you read the definitions of two quality concepts—defect and defective, shown in Figure 9.11—the meaning may not be clear. However, if you study the visual examples below the text, the concepts are more understandable.

Although our book focuses primarily on visuals, it's appropriate at this point to mention the impact of words on visual imagery. Strunk and White's classic Elements of Style (1999) exhorts authors to "write in concrete nouns and verbs," because simple visual images communicate clearly. Compare these two paragraph titles from a geology text: Volcanic Eruption and Geological Event. Which one conjures up a visual image? Clearly the first title is more concrete and leads to visual imagery.

In Chapter Three we discussed dual encoding as the basis for greater memorability for content presented visually. According to dual encoding, a graphic that is congruent with text adds a visual code to the verbal information in the text. Together the two codes increase the probability of encoding and retrieval. In a similar way, words that are concrete will induce the learner to form their own mental image and thus be encoded in both a verbal and a visual mode to result in better learning. Therefore, concrete language will often lead to better learning than abstract text.

In addition to concrete language, visuals promote learning when they support the content and goal of the lesson. Thus memory learning is promoted by representational or mnemonic visuals. However, as discussed in Chapter Eight, deeper learning needed for problem solving or interpretive tasks (tasks we defined as far transfer) will benefit from any of the explanatory classes of visuals including organizational, relational, transformational, and interpretive.

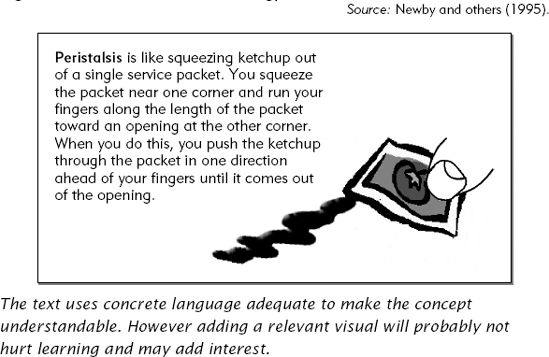

Analogies are an effective way to explain new content in familiar terms. Analogies help learning provided they use content that is concrete and familiar to the learner and that they draw from a different domain than the lesson content. For example, a research study showed that biological concepts such as peristalsis benefited from concrete analogies such as squeezing ketchup from an individual serving packet (Newby, Ertmer, and Stepich, 1995). From a learning perspective, an analogy presented in concrete and specific language is likely as effective as the same analogy presented graphically. That's because the readers would most likely form their own mental image of an analogy presented with specific concrete language. However, presenting the analogy with a visual and descriptive text as in Figure 9.12 will likely add interest to the materials. Therefore, we recommend that you develop effective analogies to teach concepts and principles and use both text and visuals to present them.

To sum up the ideas in this chapter, you can spark learner interest in your training materials by adding visuals that do not disrupt cognitive learning processes. Effective visuals correspond to the ideas presented and to the goals of the lesson. Interest does enhance motivation. To add interest in ways that do not depress learning, use visuals that are job-relevant to draw on personal interest of the learners and visuals that improve the understandability of the materials to draw on cognitive situational interest. Avoid visuals designed to stimulate emotional interest as these have been proved to have negative consequences on learning.

In this section we have looked at how graphics can affect the basic psychological events involved in learning including attention, activation of prior knowledge, minimization of mental load, building of mental models, transfer of learning, and motivation. Our assumption throughout these chapters is that a given visual will interact with all your learners in the same way. However, do all individuals process visuals alike? Do some learners have visual learning styles while others have verbal styles The next chapter addresses individual differences in learners that research has shown will affect the processing of graphics.

Harp, S.F., and Mayer, R.E. (1997). "The Role of Interest in Learning from Scientific Text and Illustrations: On the Distinction Between Emotional Interest and Cognitive Interest." Journal of Educational Psychology, 89 (1), 92–102.

Wade, S.E. (2001). "Research on Importance and Interest: Implications for Curriculum Development and Future Research." Educational Psychology Review, 13 (3), 243–261.

CHAPTER OUTLINE

Visual versus Verbal Learners

Three Individual Differences

Guideline 1: For Low Prior Knowledge Learners, Add Graphics That Are Congruent with Text

Why Graphics Help Low Prior Knowledge Learners

Guideline 2: For High Prior Knowledge Learners Use Only Words or Only Visuals

Guideline 3: Encourage All Learners to Process Visuals Effectively

Encouraging Visual Literacy

Guideline 4: Visual/Verbal Style Preferences May Not Predict Effectiveness of Graphics

Spatial Preferences versus Spatial Aptitude

Three Types of Spatial Ability

What Is Spatial Span?

Guideline 5: Minimize Demands on Spatial Span by Displaying Visuals in a Synchronized Rather Than a Successive Manner

Iconic versus Spatial Visualizers

Guideline 6: For Spatial Tasks, Provide Visual Support to Help Low Spatial Learners Succeed

Identifying Low Spatial Ability Learners

Accommodating Individual Differences: A Summary