TEN

Tips for Designing and Facilitating

Brainstorming Retreats

Before it was possible to conduct innovation challenges online, they were conducted in face-to-face (FtF) settings known as brainstorming retreats. Online challenges, of course, do not preclude the possibility of FtF retreats. In fact, they sometimes may complement and augment each other. For instance, an organization first might want to conduct an online challenge to generate a large pool of ideas and then narrow them down to the best concepts. These concepts then could be explored more fully in a FtF retreat that would provide opportunities to interact with others in real time. Another option would be to hold an online session and follow it up with a retreat to generate additional ideas.

The type of communication environment used, however, has no effect on the need to use well-framed innovation challenges. People come to retreats with the same preconceived perceptions of challenges as when participating online. So, the same amount of attention should be given to framing challenges for FtF situations. It also is possible to introduce a competitive element into retreats by having small groups compete against one another.

More important, retreats provide a vastly richer media environment for idea generation. That is, retreat participants have more cues—both verbal and nonverbal—to use when interacting with others. And, they can use these cues in real time—although online sessions also can involve synchronous communication, of course. This means that, in person, it typically will be easier and faster to collaborate, clarify, and build off other people’s ideas than is possible online. Retreats have disadvantages as well. Interpersonal conflicts and dominating individuals may make it difficult to ensure equal participation to make use of the range of insights available in a group of diverse brainstormers. However, certain group brainstorming techniques can help overcome some of these disadvantages (see Chapter 9).

This chapter is designed to provide some tips on how to design and facilitate brainstorming retreats. Parts of this chapter were taken from a similar chapter in my book Idea Power, also published by AMACOM. However, this chapter contains new information, although it is not intended as a comprehensive guide; other books exist on all of the specifics involved in conducting successful retreats.

Considering how to conduct a brainstorming retreat involves the same basic thinking processes and many similar activities involved in conducting online innovation challenges. Specifically, both require up-front preparation to lay the groundwork and follow-up activities to ensure successful implementation. The previous chapters in Part I of this book discussed many of these activities such as conducting Q-banks and C-banks and how to write challenges (Chapters 2, 3, and 4, respectively). Topics covered in this chapter for retreats include obtaining buy-in from stakeholders and upper management, using an in-house coordinator, assessing creativity readiness, managing expectations, creating an idea generation agenda, setting up the physical setting, choosing retreat participants, establishing ground rules, controlling pacing and timing, recording and evaluating ideas, and conducting post-retreat activities. Many of these activities also apply to online challenges.

OBTAINING BUY-IN FROM STAKEHOLDERS AND

UPPER MANAGEMENT

If major stakeholders are involved from the outset with an innovation challenge, they are more likely to support the project throughout. As discussed previously in this book, involving stakeholders as participants of Q-bank and C-bank processes usually helps to ensure buy-in. However, it is important that they actually perceive and experience this; otherwise, they may sabotage later efforts or at least present minor obstacles to slow down implementation. In my experience, such buy-in typically occurs unless there are any simmering conflicts.

As with most organizational decisions, you must obtain approval for a retreat from the highest necessary level. Besides simple budget approval, management must understand and agree with the retreat’s objectives. Otherwise, the outcome may be ignored or you will face an uphill implementation battle. Of course, prior management approval won’t guarantee success, but it will make it easier to gain a fair hearing for the new ideas produced. The key phrase here is highest organization level.

Most managers recognize the importance of this guideline. In one organization I worked with, however, a personal conflict caused a manager to overlook it. Although the setting was not an off-site retreat, the incident still illustrates the need for upper-level support: My contact set up an afternoon meeting with a group of upper-level managers to discuss strategic issues. At a meeting that evening, I met the divisional director of worldwide company operations, who had not attended the afternoon meeting. I was somewhat surprised and curious about his absence; however, I just assumed he was occupied by other matters. I later learned he had been excluded intentionally by my contact. Apparently, they had a history of interpersonal conflicts, and excluding the higher-level manager clearly would send a message. Because of this slight, however, the lower-level manager found it difficult to gain support for the project. Although it may be obvious what we should do, we sometimes allow our emotions to interfere. Avoid cutting off your nose to spite your face.

In another organization, I kept pushing my in-house contact to obtain buy-in at the highest level and let me know who that person was and, most important, if that person approved of the objectives, scope of the project, and how the retreat would be conducted. And I asked these questions several times via e-mail and phone conversations over a period of several weeks. I was continually reassured that everything was fine and that necessary approval existed for conducting the retreat and for how it was going to be conducted. Now, you probably can see this coming: At the end of the first day of the two-day retreat, a senior manager walked in. He surveyed the flip charts, sticky notes, and toys we were using to provide a creative environment; and asked something to the effect of, “Who the heck approved all of this? What’s going on here?” I never did learn the outcome of that event—it’s probably just as well!

Another aspect of obtaining buy-in involves the specific area of buy-in. Sometimes it isn’t enough to have approval at the highest necessary level with respect to conducting a retreat and the process used to generate ideas. The idea evaluation and concept formation phase of innovation challenges also requires top approval. In one company, I met personally with the highest-level-possible manager, and described the process I planned to use in detail. He approved everything I said. During the second day of the retreat, this manager showed up while the participants were evaluating ideas. He noticed that one of his pet ideas wasn’t selected for future consideration and expressed his consternation that this idea wasn’t chosen. I told him he was the boss and he could throw it into the idea concept “hopper” if he wanted. And he did. It later was refined by the participants, who then agreed it should have been selected initially because some modifications had improved it considerably.

SELECTING AN IN-HOUSE COORDINATOR

As with any group activity, coordination is needed to plan and conduct a retreat. An official coordinator will make it easier to conduct a successful retreat. His or her duties typically include choosing an outside facilitator, collecting planning data, choosing participants and keeping them informed, making arrangements for physical facilities, and monitoring postretreat activities. However, don’t wait until the retreat to involve a coordinator. The coordinator should be appointed to oversee all retreat activities, beginning with initial planning.

Choose coordinators based on their ability to do the job and relevant experience. (Don’t appoint a coordinator if his or her only previous experience was planning the company picnic!) Planning a retreat involves special skills because of its heavy task orientation and its importance to the company. The person you choose should relate to others well and be able to monitor group tasks closely. Other skills include the ability to coordinate many details simultaneously, communicate in a positive manner to encourage commitment, and be aware of the importance of teamwork and ownership of the results.

Although coordinators have an important responsibility, they may not be the best choice to serve as overall retreat facilitators. A different set of skills is needed to design a retreat and see it implemented. Unless coordinators have special expertise in these areas, you should use an outside person.

MANAGING EXPECTATIONS

Either the in-house coordinator or an external facilitator should assess expectations and clarify misconceptions. This should be done for both organizational decision makers and retreat participants.

In some organizations, high-level managers view retreats suspiciously. Their expectations and understandings may differ from those of the retreat’s planners. Managers often believe that individuals are paid to solve problems and retreats are just an excuse to party. I have heard this sentiment occasionally and believe it is shortsighted thinking. A well-planned and coordinated retreat can be productive, and it can be tied directly to long-term effectiveness. Most important, retreats can provide a pool of ideas that can complement and enhance online challenges. Management usually just needs a little convincing.

After assessing expectations, the best way to clarify them is to give a balanced presentation of retreat strengths and weaknesses. You make a more convincing argument when you present both pros and cons; otherwise, the person you want to persuade may think you are hiding something. The other person also is more likely to believe he or she controls and owns the decision; therefore, commitment to the retreat and its outcome should be higher as well.

Perhaps the most important set of expectations to manage are retreat outcomes. Such outcomes typically are expressed as the quantity and quality of the ideas generated, as well as an organization learning a new process methodology to use for future idea generation projects. There is, of course, no guarantee that a challenge will be resolved to everyone’s satisfaction. If the retreat is planned well, however, the odds of a successful outcome will increase dramatically.

Besides the usual rational arguments, many managers respond to the bandwagon syndrome: If everyone else is doing it, maybe we should, too (or at least take a closer look). I don’t necessarily advocate this approach, but it may help occasionally. Managers learn other companies are having retreats and decide to follow suit. Monkey see, monkey do.

Although it would be disastrous to overlook managerial expectations, it also would be a mistake to neglect participant expectations. In many organizations, subordinates are not consulted about managerial decisions; thus, it is unlikely they would be contacted regarding a retreat’s agenda. The high degree of employee involvement in a retreat mandates some participation during planning, however. At least one or two employee representatives should contribute to pre-retreat planning. If nothing else, give employees a chance to look over the agenda and offer opinions. And, as noted previously, some or all participants may be stakeholders who can participate in pre-retreat Q-banks and C-banks. This inclusive approach now is used more with the current emphasis on open source management.

ASSESSING CREATIVITY READINESS

Another pre-retreat consideration is to ensure that participants have creativity readiness. Participants should be predisposed to creative thinking; there should be no hidden agendas or other issues to deal with before idea generation. For example, some teams need basic team-building skills before they can develop a more creative climate. Matters such as interpersonal trust and cooperation often need attention before creative ideas can be generated. Groups must be able to function as a team before they can exploit their creativity. In one session I facilitated, the participants expressed a need to voice their concerns about a company administrative policy. It was obvious these concerns needed airing before any productive idea generation could take place. Once they were, the members were able to focus their attention on the purpose of the retreat.

CREATING AN IDEA GENERATION AGENDA

Retreat success often depends on how much structure you build in—generally the more structure, the greater the likelihood of success—but such structure must be used flexibly. You will have to modify almost any plan. If some groups do not respond well to one technique, offer backups. So, if you have underestimated the time needed, bring out backup techniques. For instance, schedule more idea generation techniques than time available—typically ten in total, although six or seven actually may be used. The situation is something like cutting a piece of wood to fit an area of defined length. If you make the cut too short, you can’t correct it; if the cut is too long, you will have the option of trying again. So, it’s better to err on the high side.

One important agenda consideration is the order in which techniques are used. I recommend starting with a brainwriting technique in which participants write down all the ideas they have brought with them to the retreat. I then follow it with one or more techniques that rely on stimuli related to the challenge, and then alternate with methods relying on unrelated stimuli. I also have found it useful to introduce a playful technique in late morning or especially near the end of the first day. One popular approach for this method is to have participants write ideas on multicolored paper airplanes, throw them to each other, and then use the ideas for stimulation to write down another idea and throw the planes again. (This is the Fly Ajax method listed in the sample agenda that follows.)

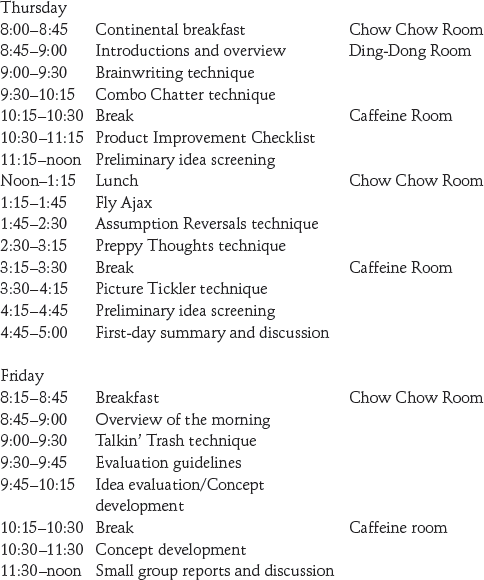

A detailed agenda is a primary planning goal. It should include a sequential description of major activities and the time allocated to each. However, be flexible in your approach. View an agenda as a game plan that can be modified as situations arise. A sample agenda for a one-and-a-half-day retreat is as follows:

RETREAT AGENDA

Veeblefeester Widget Corporation

Dallyshowers Resort

I designed this retreat so that idea generation and evaluation would be separated. The participants spend most of the first day using a variety of techniques to generate ideas. They are divided into small groups and as group members think of ideas they write them on sticky notes, one idea per note. It is important to emphasize this point because later idea evaluation involves moving ideas around. Each group should have two flip charts with one reserved for the “best” ideas and the other for “other” ideas, so as to avoid any negative connotations. The groups place their ideas on the “other” flip chart as they write them down. After time is called for each technique, each group evaluates its ideas, places the best ones on the appropriate flip chart, and then takes turns sharing the ideas with the large group. At this time, the other participants can add to or think of any new ideas stimulated, writing down all modified or new ideas on separate sticky notes.

Once all of the groups have shared their best ideas, they place their flip-chart sheets on two different walls of the room, with one for “best” ideas and the other for “other” ideas. Participants typically vote on all of the ideas posted on the walls at the end of the first day (and sometimes at the end of the first morning). These minievaluation periods help shorten a long list of ideas, prompt suggestions on how to combine related ideas, and stimulate thinking for more ideas. Participants typically use colored, sticking dots to vote for their favorite ideas, using successive voting rounds. For instance, in the first round of voting, participants might be given ten blue dots and told to vote for their favorites (one dot per vote). Next, they might be given five orange dots and told to vote on their favorite ideas that received at least three blue dots.

I set aside the morning of the second day primarily for idea evaluation. However, I suggest using one idea generation technique first thing to capture any ideas thought of overnight. The rest of the morning, the participants should focus on idea evaluation. For this, groups should select or be assigned a highly rated idea to refine and develop into a workable concept to implement. This promotes a sense of task completion and may increase the commitment to certain ideas. It also can smooth implementation after the retreat.

I also limit the length of the retreat. There is nothing sacred about an eight-hour day. The intensity and concentration called for in retreats often make it impractical to stick to a traditional work schedule. Thus, some groups might benefit from an early finish, but if the groups are energized and seem productive, allow them more time.

Finally, it can be beneficial to stay over at least one night during a retreat. For instance, you might want to schedule informal social activities for the evening. Such experiences promote team building and contribute to a positive problem-solving climate. When I suggested this to a company vice president, his major concern was that some people would drink so much they would be useless the next day. However, I conducted a retreat for another corporation that illustrates the positive value of social affairs. The first day was not as successful as we had hoped. There was a lot of negative thinking and an unwillingness to take risks. During an evening social hour, however, several participants loosened up and suggested ideas that later were judged promising by management.

SELECTING A LOCATION AND ROOM SETUP

Although not as important as other factors, this matter still deserves attention. If resources permit, consider an off-site location removed from daily distractions. However, the location should be accessible by conventional transportation. If people must be ferried in using two-seat airplanes or portaging with canoes, you may want to rethink the location!

Be wary of hotels trying to pump up their convention business. Instead, consider resorts. Although many resorts cater to meetings, seek out those that specialize in conferences—they usually can anticipate your needs and deal with crises better. You also can use their personnel to arrange details. Always check to ensure things are done correctly, however. Sometimes, simple misunderstandings can create major frustrations. For instance, I once requested rooms with round tables only to find a classroom arrangement with straight rows of rectangular tables—perfect for a lecture, but not for small-group interactions.

Although it often is overlooked, the view—if any—from the rooms should be evaluated. Participants can be distracted by beautiful scenery if the view is overwhelming. (The only time scenery was a significant problem in one of my retreats was when the “scenery” was female. The meeting had glass walls and overlooked a swimming pool. As a result, the all-male groups in these rooms had dilated pupils for the first hours of the day.)

CHOOSING RETREAT PARTICIPANTS

People attend retreats for a variety of reasons. Usually, they attend because they work in a particular area or have special expertise. Occasionally it is a reward for outstanding performance. If you can select participants, look for those who are highly motivated by the topic, knowledgeable about the problem, and willing to generate and consider off-the-wall ideas. And, of course, people with a direct or indirect stake in the outcomes should be involved.

I generally recommend that organizations conducting retreats use both internal and external participants. Internals should include stakeholders (including employees from other divisions, if appropriate), personnel with problem knowledge, and a few participants without knowledge of the problem. Motivated and, especially, creative people from office support staff to upper management often can provide a diversity of fresh perspectives. (Such employees often receive a morale boost from being included, which can result in a more creative climate.)

There are two types of externals who should be included. I call the first type external e-stormers because they are not members of the organization but submit their ideas electronically, as described in Chapter 7 on idea management software. These individuals can participate from anywhere in the world and typically offer new perspectives not considered internally. As discussed previously in this book, these externals can participate with internals on submitting ideas during innovation challenges, thus significantly increasing the pool of ideas before or after a retreat. The second type of externals are what I refer to as brain boosters. These people work outside of an organization as creative professionals and/or as creativity consultants. I recommend including one of these individuals within each small group at a retreat. Often these individuals also have facilitation skills they can employ within their groups.

ASSIGNING PARTICIPANTS TO GROUPS

Limit groups to five or six people. Don’t vary from this guideline, even if the resort sales personnel say they always set up tables for ten people—that just makes their job easier. It’s not in your best interest. Some research suggests that five people is the ideal size, but I have had success with as few as four and as many as ten—it all depends on how their interactions are structured using idea generation techniques.

In larger groups, participation may be unequal because of cliques or simply sheer size. Cliques form when interactions among group members become difficult; it’s easier to interact with four or five people than with eight or nine. Unequal participation also can occur; the larger a group, the fewer opportunities to participate. In small groups (four or five people), on the other hand, there are fewer resources to draw upon and a dominating individual may emerge.

More important than size, however, is group composition. Whenever possible, don’t mix bosses and subordinates. In one retreat I facilitated, a manager insisted on being in a group with his subordinates. It didn’t take long for me to figure out why the group was not generating many ideas. The boss apparently was conducting a new product idea generation session the way he conducted staff meetings. He would call on group members by name and ask for their ideas. Then he would criticize each idea as it was suggested. By dominating the discussion and criticizing ideas, he put a damper on the whole process. The subordinates were afraid to suggest any “wild” ideas. Instead, they tried to play it safe and suggested carefully thought-out ideas. It’s difficult to think of carefully analyzed ideas and still be spontaneous; as a result, the ideas were few and mundane.

You also should use homogeneous or natural work units only if particular expertise is needed. Natural groups become stilted in their thinking and need fresh input from others. If you work with the same people on the same problems every day, you’re likely to get the same old solutions. In contrast, groups composed of personnel from different teams can bring new perspectives. For instance, if a problem calls for engineering expertise, a natural work group of engineers may be needed. However, if the problem is more general, interdisciplinary teams will be more effective. Or, at least include people from different departments within the same groups.

In general, each small group should have one or more people knowledgeable about the challenge and one or more internal and external creative types. So, a group of five people might contain three internal experts from different departments, one external brainbooster, and one or more internals who do not work in the area of the challenge. I also advocate periodically rotating the composition of group membership, especially if most groups seem to be wearing down or are having trouble generating ideas. The afternoon typically is the best time to do this. One caution: If a group seems to be “on fire” with rapid and sustained idea generation, I would keep them together for a while longer.

By the way, one tactic to control conflict or dominating personalities is to form a group of so-called problem people. Before one retreat, we identified all the troublemakers, malcontents, and obnoxious people—and put them together in one group. We then let them fight it out and bother each other. Our attitude was that if they don’t produce any useful products, at least they will not bother others. A disadvantage of this approach is that some creative individuals may be excluded. I recommend using this tactic only as a last resort; a skilled facilitator usually can deal with most disruptive behavior.

ESTABLISHING GROUND RULES

The first task of a retreat facilitator is to review the ground rules. From the outset, you should clarify expectations and establish boundaries of acceptable behavior. If people know what to expect and what the limits are of permissible behavior, they should act appropriately.

The following are some sample ground rules a facilitator might read and distribute in writing to a group:

•Separate idea generation from idea evaluation. Try to withhold all judgment during idea generation. Once all ideas have been generated, you will have the opportunity to analyze them. This is the most important ground rule, so remind your fellow group members if they start to violate it.

•Do not be a conversation hog. To benefit from all the resources represented by the group members, limit your comments.

•Try to forget potential implementation obstacles when generating ideas. Even wild ideas are acceptable, since they often can be modified or serve as stimuli for other group members.

•Try to stick with the time schedule. However, don’t be afraid to deviate if needed. For instance, if one technique helps to generate ideas, don’t stop using it just because the scheduled time has passed. Your facilitator will work with you on this.

•Try to generate as many ideas as possible. The more ideas you think of, the greater the odds are at least one will be a breakthrough.

•Be assertive. Your ideas are just as valuable as other people’s. Even if you think an idea is impractical, go ahead and suggest it. It might prompt other ideas.

•Have fun. Don’t worry about being silly when generating ideas.

You should establish ground rules during planning so participants won’t be surprised by them; however, if you can’t, explain the rationale for each rule when offered. If there are any special participant considerations, discuss and incorporate them as new guidelines if the other members agree. For instance, nonsmokers often request a smoke-free group or a limit on how many people may smoke simultaneously.

CONTROLLING PACING AND TIMING

Although planning is the primary determinant of success, the control of retreat activities runs a close second. Most of us have suffered through group experiences that can be characterized at best as aimless wandering. Avoid this problem by monitoring each group’s activities and supplying structure as needed. One way to supply structure is to control the timing and pacing of activities.

Obviously, the smaller the facilitator-to-group ratio, the better that timing and pacing can be controlled. The only exception is in organizations with groups experienced with problem-solving techniques. Their experience often can substitute for facilitator skills, since experience is a form of structure.

To control pacing and timing, observe how groups respond to each technique; then move them from one technique to another based on their performance. Not all groups respond equally well, any more than individuals do to different teaching or counseling methods. Often, consensus develops within a group that a technique “just doesn’t work.” At one retreat, a participant responded, “This technique is a red herring.” At the very next retreat I conducted, I heard nothing but positive comments about the same technique. Moreover, some groups respond so well to a technique they resist moving to another. In either case, a facilitator should allow the groups to make necessary adjustments.

Technique effectiveness depends on many factors such as group climate, problem type, and group-member motivation and experience. If a technique doesn’t stimulate ideas, allow the group to move on or return to one that worked well before. But if a group is highly fluent and generates many ideas, don’t break the flow and force it to learn another technique. In this case, the group climate will do more to prompt ideas than an imposed technique.

To determine proper pacing and timing, evaluate a group’s familiarity with a technique and experience using it. Don’t force a technique on a group if the members have little experience or familiarity with it. This is why minimal training is so important; usually a simple explanation, illustration, and short practice session will be enough. The time available also will be an important factor. More complex or time-intensive methods should be reserved for when there is adequate time.

The other activities for both retreats and online innovation challenges are the processes of selecting and evaluating ideas and implementing solutions. These topics are discussed in Chapter 11.

EVALUATING DATA

Use a systematic evaluation procedure to ensure that all ideas receive a fair hearing. This can be difficult if there are many ideas and you have little time. Many productive idea generation sessions deteriorate during idea evaluation. Faced with too much to do in too little time, group members feel pressured and choose just any idea to implement. Such an approach rarely results in a high-quality solution.

To overcome this problem, agree upon and stick with a structured evaluation approach. Although these methods vary in complexity, the evaluation process should become more manageable. For example, include a preliminary idea evaluation segment in the retreat agenda. In the agenda I presented before, group members evaluate ideas after the morning and afternoon sessions. This first screening culls out obviously unacceptable ideas, and it may stimulate thinking for new ideas or modifications of existing ones. To guide this process, use one or two major criteria. For instance, you might eliminate ideas that cost more than $1,000 and call for more than two people to implement.

A second way to structure idea evaluation is to use weighted criteria. In the previous example, cost and time criteria are equal in weight, since no mention is made otherwise—that is, cost and time are equal in importance and both should be used to judge the idea. Although equal weight may work for an initial screening, more-refined analyses call for more-refined rating methods. Because people perceive idea evaluation criteria as similar in value, rating procedures should take into consideration different degrees of importance for the criteria. For instance, when buying a car, most of us believe that gas mileage and price are more important than color and seat cover material.

One simple culling approach involves making a list of the advantages and disadvantages of each idea. You then choose ideas with more advantages than disadvantages for further consideration. Another approach is to allocate votes to each group member based on a percentage of the total number of ideas. For instance, if there are one hundred ideas and the allocation percentage is 10 percent, each member receives ten votes. The members then allocate their votes any way they want, placing all votes on one idea, dividing them equally among ten ideas, or using any other combination.

DEVELOPING ACTION PLANS

The importance of implementation action plans should be self-evident. Unfortunately, because of either time limits or distractions, we often overlook implementation during a retreat. The sun or slopes may be inviting, or group members simply may burn out from idea generation and evaluation. It is right after idea generation and evaluation that important implementation issues may arise, however. After a retreat, people may be too busy to deal with retreat-generated problems. Nevertheless, you should try to set aside time to deal with implementation.

Consider appointing an implementation monitor and assigning individuals to complete general tasks. If possible, discuss the when, where, and how of these tasks—that is, have the group specify the completion dates, locations, and details. You also might construct an implementation time line to provide an overview of the completion of each primary activity; you could develop a more refined schedule later.

PLANNING POSTRETREAT ACTIVITIES

If you sketched out an implementation plan during the retreat, it should be easy to elaborate on later. However, just because something is easy, it doesn’t mean motivation and time are available. You may have to find the motivation and make the time to benefit from the retreat. Don’t give up now. The four guidelines that follow will ensure that your efforts weren’t wasted:

1.Develop a final implementation schedule. If you laid the groundwork for implementation during the retreat, a project manager can develop a more formal implementation schedule. Several software programs will simplify this task. Most are based on variations of program evaluation and review technique (PERT) charts, which compute the sequence and duration of various activities. You also can use text outlining and object-oriented graphics programs to design elementary implementation plans. They are easier to learn and much less expensive than high-priced project management software.

2.Verify that all plans are implemented as scheduled. Just having a plan doesn’t guarantee that it will be implemented. Assign someone the role of implementation monitor. It is important that this person be detail oriented and able to oversee several activities simultaneously. The monitor also should be skilled at motivating people to complete tasks and should work well with others.

3.Keep upper management informed. This guideline also should be obvious; however, internal political struggles or simple mistakes in communication with management often happen. Therefore, management may believe it is ill informed about retreat results. That is not good. Upper management probably footed the bill for the retreat and has a vested interest in it. I have attended some postretreat feedback meetings with upper managers, and they take the results seriously. You should, too.

4.Provide feedback and involve participants. Besides general communication complaints, a lack of feedback is probably the second most common gripe I hear from employees. Because of the time and effort they invested, you should keep retreat participants informed about outcomes. Most participants are interested in answers to the following questions:

•What decisions were made?

•When will they be implemented?

•Who is responsible for implementation?

•How did upper management react to the overall retreat?

Informing participants is a low-cost activity that yields high dividends. At the least, send a memo with results of the retreat (the most popular ideas) and postretreat outcomes (what happened to the ideas).

You also might involve some participants in implementation activities. Participants could assume direct responsibility for specific tasks or supply information and opinions. In any event, involvement creates a sense of ownership of a project and increases commitment to it.

CONDUCTING AND FACILITATING

PROBLEM-SOLVING RETREATS

Feedback is a two-way street. You also should ask retreat participants their reactions. What did they like best? What worked least well? What should be done to improve the next retreat? How satisfied were they with their groups? How would they rate the performance of the facilitators? These and other questions can help planners improve future retreats.

Begin planning for a follow-up retreat. If you don’t conduct retreats frequently, a follow-up may be needed. One issue rarely can be resolved satisfactorily during a short retreat. This is especially true of strategy-planning retreats, where there may be unfinished business.

When planning new retreats, consider the results of previous retreats and participant feedback. Although this may seem obvious, we often repeat mistakes. Because of the passage of time or turmoil of current events, we frequently forget what we learned. However, even simple revisions can lead to major improvements. Thus, dig out retreat evaluation data to use as a planning guide.

Depending on the problem or topic, conduct follow-ups between three months and one year later. Annual retreats also may be needed to deal with long-term issues. You’ll find that follow-ups create a sense of continuity and commitment to resolving organizational problems.