CHAPTER 4

Building Your Business Case

Creating the Logical and Emotional Foundations of Your Argument

We’ve covered the crucial background information: persuasion fundamentals, decision making, and key aspects about your target. The next several chapters will cover what I call your “Persuasion Equation.” This is the combination of factors that will result in a rocket-fueled approach to you getting agreement.

Your Persuasion Equation is:

(A Great Business Case + Your Outstanding Credibility + Compelling Language) × Intelligent Process = Yes Success

In this chapter, we’ll focus on building your business case. This is a great way of performing your due diligence to ensure your persuasion priority makes good sense for you and your target. It’s also a good time to get to know more about your target. Going through this process will give you the content you need to convincingly make your appeal to others.

A solid business case requires two primary building blocks: logic and emotion (Logos and pathos for you Aristotle fans). The old saw, “Logic makes you think, and emotion makes you act,” has been around so long for a reason: It works! Let’s first take a look at logic.

Logic has many components: deductive reasoning, inductive reasoning, abductive reasoning, just to mention a few. But this isn’t an abstruse exploration in navel gazing, so we won’t spend time making philosophical arguments for how many angels can dance on the head of a pin. In business, if you want to appeal to logic, you do so with quantifiable measurements. That’s right, numbers.

QUANTITATIVE REASONING

Evaluation of numerical data is crucial when building a compelling business case. (Hey, I never promised there wouldn’t be any math in this book!) Stick with me here; you’ll be glad you did.

To be successful in business today, financial literacy is a must. You’ll never reach your persuasive potential if you are terrified of your calculator. You need to know how to read and understand the basics of an income statement, a cash flow statement, and a balance sheet. You also should appreciate that, like persuading your target, working with financial figures can be an interpretive art form.

Here’s what I mean: Let’s say you work for a bio-friendly consumer products company that makes natural surface cleaners like you might use in your kitchen. Now, let’s say you invested $100,000 in a marketing initiative that generated $1,000,000 in kitchen cleaner sales. Was your return $1 million, or was it $900,000? Or maybe it was yet another number? What do you think? Well, actually, the answer depends on who’s doing the math!

Nonfinancial types often have trouble grasping financial disciplines, because many think of them in terms of black and white. Accounting is not an exact science; many gray areas exist. Financial reporting and forecasting are open to interpretation, judgment, and approximation, as are generally accepted accounting principles (GAAPs). In the example above, salespeople may claim a return of $1 million, the marketing team may argue the return is $900,000, and your accounting group may have other ideas. We’ll talk more about this in a bit.

Seemingly simple ideas such as revenue (which in some organizations is called “sales revenue” or “gross revenue”) aren’t etched in stone. For example, when is that revenue “recognized” (an accounting term meaning “counted”)? Is it when the purchase order is signed, when the goods are delivered, when the invoice is sent, or when the money hits the company’s bank account? See? Ambiguities open up multiple interpretations.

Much like social and corporate culture norms, financial norms must be determined and adhered to. More than likely, you won’t have sole responsibility for actually performing the following calculations for your company (that’s what financial analysts are for), but you should have the financial literacy to know how numbers are generated and what they mean. When you do, you’ll be able to speak the language of finance, ask more insightful questions, and use that information to create more compelling quantitative cases for your persuasion priorities.

As you build each case, consider as many positive aspects as you can: If your initiative could boost product market share in the Northeast by 8 percent, what might it do in other regions? Are there international implications as well? And don’t forget multiplicity. If your idea would increase employee efficiency, thereby saving the company dollars, make sure you apply that savings to as many people as appropriate. Are there tangential benefits? If you sell more of product A, will increased sales of product B follow? To increase the persuasiveness of your case, consider all the benefits.

If you internalize the ideas in this section, I guarantee you’ll be in the top 10 percent of all professional persuaders.

Return vs. Return on Investment (ROI)

Here’s the first financial aspect that has the potential to be confusing: What’s your initiative’s worth to the organization? You may hear some people say, “What’s the ROI?,” to which another person responds, “One million dollars.” Well, that’s not exactly accurate.

ROI, by definition, is always a ratio. Some kind of “return” or “profit” divided by the investment that generated said return. As described above, many people think of the return portion of ROI as the ROI, but this is technically incorrect. You don’t need to point out that those people are wrong; just understand that when someone claims the ROI as a particular dollar amount, he’s talking about just the return portion of the “return on investment.”

Dollars Returned. When talking about just the dollars returned, the calculation is pretty straightforward: How much did you invest, and how much did you receive in return? Let’s use our earlier example: You invested $100,000 in a marketing campaign, which in turn generated $1 million in sales, or gross revenue.

Gross revenue ($1 million) – marketing costs ($100,000) = dollars returned ($900,000).

Simple, right?

Well, we’re not quite finished, because we haven’t taken into consideration the costs of goods sold (CoGs). The most obvious CoGs are wholesale costs required to produce or acquire a product, as well as sales commissions from selling that product. What must you pay to sell the item? Your project may or may not have CoGs, depending on whether it’s a product or a service. But if CoGs are involved, it is imperative you include these costs in your calculations.

So, let’s crunch the numbers again with this perspective in mind, assuming that our CoGs to produce and sell are $500,000:

(Gross Revenue – CoGS) – Marketing Investment = Dollars Returned

($1 million – $500,000) – $100,000 = $400,000 returned

The dollars returned in this example can be considered gross profit. If you want to appear reasonable, conservative, and responsible to senior management, use the gross profit number as the basis for your dollars returned. Now what about ROI?

Return on Investment (ROI)

As mentioned earlier, ROI by definition is always a ratio; that’s the “on investment” part. A ratio demonstrates the quantitative relationship between two numbers, showing how many times one number contains the other. ROI establishes the relationship between the return and the initiative’s investment. In our example above, the project has a $400,000 return and a $100,000 investment. With RO I, the most elegant way to write this is with a colon, which can simply be expressed as ratio of 4:1.

Typically, when using ROI ratios, whatever you invest is always simplified to 1. But the return can be shown in fractional amounts. So, if the marketing campaign example above cost $150,000 (instead of $ 100,000), you would simply divide $400,000 by $ 150,000 and find the quotient to be 2.666 (which we round up to the nearest tenth, making it 2.7). That makes your ROI ratio 2.7:1. That number is not as compelling as our original example, but it’s still not a bad return!

ROI as a Percentage. Expressing return as a percentage is even more common and, perhaps, even more persuasive. Let’s go through the steps, using the same figures as in our previous example:

Step 1: Calculate gross profit, as above.

(Gross Revenue – CoGS) – Marketing Investment

= Return

($1 million – $500,000) – $100,000

= $400,000

Step 2: Divide the gross profit by your investment amount to determine a factor.

$400,000 ÷ $100,000 = 4

Step 3: Multiply that factor by 100 and express the return as a percentage.

4 × 100 = 400%

Why is it more persuasive? Think back to our conversations about mental impressions; 400 percent seems like a much larger number than 4:1!

Obviously, you want a positive ROI number. However, some companies go so far as to specify ROI minimums before they take on a project. If your ROI number is negative, regardless of whether your priority is good for you personally, it’s no good for your organization, and you should reconsider.

ROI and Return Challenges. The challenge with return and ROI calculations is establishing what’s included and what isn’t on both sides of the equation—the costs and the benefits. Do you calculate the hours spent by salaried employees who worked on your initiative and include that as a cost? Do you attempt to quantify improved morale and represent that as a benefit? With return and ROI, like all measures, it’s valuable to consider all reasonable inclusions and exclusions. And as already stated, every company has different ways of looking at the numbers.

One final note about return and ROI calculations: If you use these calculations to forecast anticipated ROI, you may want to run a few different scenarios, such as these: What if sales are off by a particular percentage? What if the cost of goods sold is higher than anticipated? What if the product launch is delayed? Taking into consideration multiple obstacles will show others in your organization that you’ve done your due diligence and thought through your persuasion priority.

Now, let’s talk about projects that might require capital expenditures (buildings, machines, tooling). Staying with the example of a biofriendly consumer products company, imagine you’ve developed a successful kitchen cleaner product and now want to pair it with biofriendly paper towels. How might you best frame your arguments? Here are a few ideas.

Payback Period

As its name suggests, a payback period is the length of time it takes an organization to recoup its costs on an initiative. Let’s say your persuasion priority is to obtain approval from your executive team to bring to market a new kind of eco-friendly paper towel (affectionately dubbed internally as the “Owl Towel”). It uses recycled materials and is more absorbent than others on the market, and you think it will do good things for both your company and the environment.

Working with all the necessary parties, you’ve estimated that the cost of bringing this new product to market would be $1 million. Once to market, you’re estimating the Owl Towel’s yearly revenues will be $350,000 for at least the next four years.

To determine the payback period, simply divide the investment ($1 million) by $350,000. This straightforward calculation tells you that your payback period on the Owl Towel will be 2.86 years. This payback calculation is useful, fast, and easy to communicate. Thus, it is a solid way of looking at your initiative. The bad news is that it does have some limitations. Why? Because $350,000 four years from now may not be worth what it is today. Here’s where a financial tool called Net Present Value comes in.

Net Present Value (NPV)

Net Present Value reflects what your multiyear project is worth in today’s dollars. It answers the question: What is this cash stream really worth to the organization? To understand Net Present Value (NPV), we need to break down the term to its two component parts: “net” and “present value.” If you subtract your initiative’s total outgoing cash flow from your initiative’s total incoming cash flow, the remainder will be your “net.” Now, because of costs of capital, earning potential, inflation, and so forth, tomorrow’s money is worth less than today’s money is. (Ever heard the expression, “A million dollars isn’t what it used to be”?) The “present value” part of this calculation (also sometimes referred to as “PV”) enables us to make decisions about longer-term initiatives using a notion we can wrap our heads around: today’s dollars.

To calculate Net Present Value, start by using what is known as a “discount rate.” This is the rate at which future earnings for your project are, well, discounted. Unless you are currently a financial analyst for your company, you’re going to need input from others on what an appropriate discount rate should be. Without expert guidance, you could do more harm than good for your idea and your reputation. The other reason you’ll need guidance from your company’s financial analysts is that some organizations use different discount rates for different kinds of projects (high-risk vs. lower-risk, for instance), and some even vary the discount rate based on the term of the initiative.

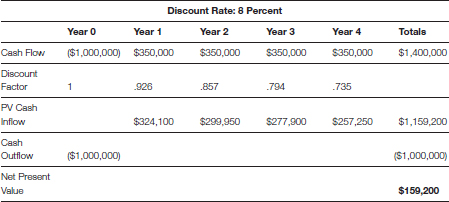

Let’s look at NPV by building our Owl Towel financial case for the executive team: We know it will cost $1 million to bring it to market, and we conservatively estimate that we’ll realize a payback of $350,000 per year. A trusted colleague in the company’s finance group suggests we use a discount rate of 8 percent (0.08).

I’m going to walk you through what some might call the “oldschool” way of making calculations, but I’m doing so to help you completely understand the calculation. Then we can talk shortcuts.

First, we will use our discount rate to find a discount “factor.” This is the factor you will use to determine the current value of the money realized by your new Owl Towel. The equation to determine your discount factor is:

1 ÷ (1 + r)t

with r representing your discount rate, and t representing the number of years. For example, our discount factor equation for the first year of our Owl Towel project would be 1 ÷ (1 + .08)1. This means 1 divided by 1.08, which equals .9259259 (of course, when rounded to the nearest thousandth—which is accurate enough for this illustration—would be .926). So to find out the Present Value (PV) of our first year’s Owl Towel earnings, we multiply the cash flow of $350,000 by .926 to discover that the Present Value of our Year One earnings would be worth $324,100.

And, just so you get the hang of this, we’ll do one more. The calculation for the second year of our Owl Towel project would be 1 – (1 + .08)2. The superscript is stating 1.08 to the second power, which is mathematical shorthand for 1.08 x 1.08. If you multiply 1.08 by 1.08, you get 1.1664. Divide 1 by 1.1664 to get .857. This is your discount factor for Year Two. Multiply $350,000 by .857, and you’ll see that the second-year Owl Towel cash flow is worth $299,950. (See how quickly the value drops? This is why Net Present Value is such an important calculation to know!) Continue using this formula for each year of your forecast.

Of course, doing the math to determine your discount factor is considered antiquated, but you should know how it works. A quick Google search for “Discount Factor Tables” or “Net Present Value Tables” is an easy way to obtain the discount factors you’ll need. Here are all the calculations for our Owl Towel NPV example:

You’ll note that the total Present Value of the Owl Towel project is projected to be $1,159,200. Subtract today’s $1 million investment, and the NPV of the Owl Towel proposal is actually $159,200. That is what your project is worth in terms of today’s dollars.

As you can see, the Net Present Value is a more accurate indicator of Return on Investment than payback calculation is. In our previous example, which ignored the time value of money, we forecasted the payback period to be slightly less than three years. Now we know from using NPV that we really won’t see payback on the project until sometime between Years Three and Four. Depending on the threshold of acceptable payback for your company, you may have to do more work to build your case. (Another term you should be familiar with here is hurdle rate, which is the minimum return your company will accept on an initiative before investing in it. Sometimes the discount rate and the hurdle rate are the same number.) Your credibility will skyrocket when you can demonstrate to others that you understand these powerful financial concepts and factor them into your business cases. Want to get really great? Wrap your mind around IRR.

Internal Rate of Return (IRR)

Internal Rate of Return is a measure related to Net Present Value and answers this question: What rate of return will the organization receive on this project? The resulting number can be used internally to compare projects and make informed decisions, such as whether your case is strong enough to convince the organization to say yes.

In its simplest form, the Internal Rate of Return (IRR) is the interest rate necessary to make your Net Present Value zero. You do that by applying a discount factor to each year and then summing your return. How do you know what rate to use? Well, this is going to sound crazy, but you guess.

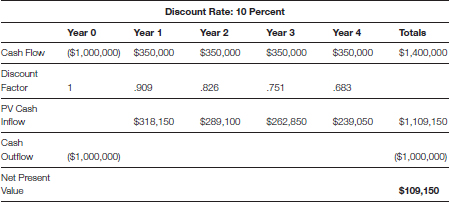

So let’s go back to the Owl Towel example and try 10 percent. (A discount factor table supplies the necessary discount factors.)

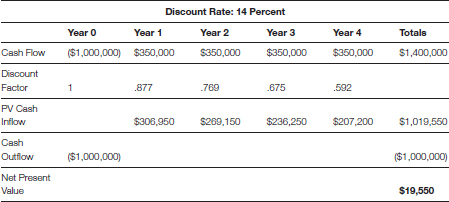

In the bottom-right cell, this calculation at 10 percent shows the NVP as $109,150. Well, that’s not zero, so guess again. Let’s try 14 percent.

Here the NPV is $19,550. That’s not zero, either!

I know what you’re thinking as you grab your head in anguish: Not more calculations! I’ll cut to the chase. The discount rate that turns your Owl Towel NPV calculation to zero here is 14.97 percent. Now, in some weird world of terminology that only CPAs understand, that discount rate you used to determine your discount factor now becomes your Internal Rate of Return. So your Owl Towel project has an IRR of 14.97 percent. IRR is an excellent way for internal decision makers to evaluate the financial merits of several projects at one time while also giving the organization a common way of speaking about a project.

How did I obtain such a precise IRR of 14.97 percent? Simple: I used an online IRR calculator. We live in a terrific age of technology, and you should take advantage of online calculators for their speed and accuracy. But, much like the spelling atrophy that sets in after relying on spell-check for too long, you won’t be fit to make a great financial case if you don’t occasionally flex your mathematical muscles. That’s why I took you through the math. But the real reason is to truly understand the persuasive power of a compelling quantitative case. See how the pieces come together, like individual shards of glass creating a grand mosaic?

Knowing these numbers, you’re better prepared to make your case for the Owl Towel to others. This is very likely one of those situations in which your financial case is strong but not overwhelming. So if you truly believe in this project and want to make the Owl Towel a reality, you’ll need to incorporate qualitative persuasion tools, such the ones we discuss later in this chapter. But before we do that, there is one other tool I’d like to share with you: breakeven calculations.

Breakeven Calculations

The breakeven calculation answers the question, “How many units do we need to sell to recoup our investment?”

For example, say your persuasion priority is to convince the buyer of a large retail grocery chain to carry Owl Towels. You want to offer them 100 pallets of Owl Towels at a special price of $14,000 each. You know that it will cost the chain $1,000 in expenses (shipping, stocking, commissions) to sell the towels on each pallet, and a single pallet of Owl Towels will retail for $20,000. How many pallets will the chain need to sell in order to break even?

For this example, you would first calculate your buyer’s initial investment and then divide that by the gross revenue (i.e., total cash inflow) of one unit sold at full retail.

Your buyer’s initial investment, therefore, is calculated thus:

Price Per Pallet × Number of Pallets = Initial Investment

$14,000 × 100 = $1.4 million

(This is referred to as a fixed cost.)

Next, find what is referred to as a “contribution margin.” How many dollars will your buyer have left after he sells your product? Here, if the retailer were to sell a pallet of Owl Towels for $20,000 and subtract $1,000 in expenses, the per pallet contribution margin is $19,000.

Finally, all that’s left to do is to divide that $1.4 million fixed cost by the $19,000 contribution margin to determine that the breakeven point for this opportunity is 73.68 pallets—or said more simply, 74 pallets. Breakeven calculations are valuable because they can help keep an organization headed toward a recognizable goal. The breakeven calculation is a favorite of sales and marketing teams because it simplifies the objective and acts as a powerful persuader; everything after the breakeven point is profit!

What It All Means

To reemphasize one of my earlier points: If you learn the above measures and can use them to build a business case for any initiative, you’ll be in the 90th percentile for global business acumen. Business today is all about becoming smarter, faster. And financial literacy is essential to the persuasive business professional. If you want to be taken seriously, you’ll want to speak the financial language of your organization.

That being said, never position yourself as something you are not. If you are not a financial expert, do not purport to be one. It is perfectly okay (in fact, it is encouraged) to say such things as, “I’m no financial expert, and we should certainly have the finance guys review these numbers. But my back-of-the-envelope calculations tell me . . .”

Better yet, establish relationships with your colleagues in the finance department and swing by their offices to see what they think. “You’re the experts,” you can honestly say. “Tell me what you think about this initiative from a numbers perspective.” Then invite them to your next meeting!

Numbers are important—absolutely. But for many the real power of persuasion lies on the emotional side of your appeal. As Albert Einstein said: “Not everything that can be counted counts, and not everything that counts can be counted.” Consider this your “transition zone” to the emotional appeal, where qualitative reasoning becomes just as important as (if not more so than) quantitative reasoning.

QUALITATIVE REASONING

Will the organization establish higher morale? Will communication be enhanced and problems more easily solved? Will silos disappear or at least be altered? Will the organization’s image or brand be enhanced? Qualitative reasoning is much harder to measure and report, but it’s worth the effort. With a bit of cognitive effort, practically any element of qualitative reasoning can be constructed to present meaningful numeric data, two most common being customer and employee satisfaction indexes.

Every organization—public and private, large and small, productor service-oriented—seeks the following if it is of sound business mental health:

- Sustained high morale

- Efficient and effective teamwork

- Rapid and accurate problem solving

- Positive repute and community “citizenship”

- Decreased distraction and disruption

- Accurate and unbiased communication

These “emotional” factors (sometimes referred to as “soft factors”) are usually the most important when it comes to presenting your case and persuading your target. Because, as you already know, logic makes you think and emotion makes you act. All the new plant cost calculations in the world are useless unless current customers are providing the repeat business and referral business to drive the expansion. Thus, your emotional appeals should deliberately and fastidiously involve soft factors, without exception. (I’ve seen million-dollar construction vehicles, capable of traveling at speeds up to 1.5 miles per hour, with rounded and streamlined sides. Why? Aesthetic appeal, of course!)

Determine which emotional factors best appeal to the other person. Don’t attempt to please yourself or choose to fulfill yourself and your needs, quantitatively and qualitatively. Rather, ensure that you address the other person’s emotional needs and push the appropriate visceral hot buttons. This is not manipulative; it is the essence of sales and persuasion.

Measuring the Unmeasurable

“You can’t measure morale!” some shout. “You can’t measure enthusiasm!” Okay, fair enough, but that doesn’t mean we shouldn’t try. I have a two-step method to help prove the unprovable. First, describe an observable behavior that you believe is an indicator of the desired result. Second, count the occurrences. If you’re seeking sustained high morale, perhaps you note whether people are on time for staff meetings, or perhaps you calculate what percentage of the staff is displaying positive emotions during a meeting. If you’re seeking efficient and effective teamwork, you count the number of times people come into your office asking for you to settle disputes. If you’re trying to build positive repute, you could count positive media mentions.

Is this a perfect method? Of course not, but it is certainly better and more accurate than using intuition alone. And, when you attach measures to the qualitative reasoning of your case, many will find it more compelling.

Emotion Basics

To be compelling, you need to conjure emotions within your target. More than 400 words exist in the English language to describe the concept of “emotion.” In fact, neurologists have even identified distinctions between emotions (the automatic brain response) and feelings (the subjective way we interpret those emotions). Depending on how thinly you’d like to slice the topic, you could literally list dozens of human emotions, probably right off the top of your head—from acceptance, affection, and aggression to pity, pleasure, and pride, to shame, suffering, and sympathy. And of course, there are various levels of intensity of any particular emotion.

To simplify things, let’s just consider for the moment that there are three categories of emotions: positive, neutral, and negative. Below are some descriptors of several emotional variations in each category.

Neutral |

Negative |

|

Affection |

Acceptance |

Aggression |

Compassion |

Disinterest |

Hostility |

Contentment |

Distraction |

Boredom |

Gratitude |

Indifference |

Regret |

Hope |

Realism |

Despair |

When we have language, as above, to describe emotions, we are better able to specifically recognize them in ourselves and others, and to work to create those particular emotions. This begs the question: Do we ever want to create negative emotions? Well, in a word, yes.

The Power of Negative Emotions

Obviously, many times you seek to create positive emotions in your target: If you want to be hired for the job, you’d like the person in charge of hiring to have interest in and believe in you and your abilities. If you’re looking to partner with a venture capitalist, you’d want your potential partner to be ecstatic about your idea. These examples are selfevident, but there also may be times when you need to provoke a negative emotion. For example, when attempting to convince a sluggish manager that it’s finally time to do something about his department’s lackluster customer service, make him feel the same frustration you, your colleagues, and your clients feel about his insufficiencies in that area. You may even want him to experience some regret, as he realizes he’s not reaching his full potential as a department head.

If you induce someone to temporarily experience a negative emotion (with the aim that it becomes the catalyst for that person to fix a problem), is that, in itself, a problem? Well, no. Beware, however, that—just like rafting through grade five white water—it’s the way in which you navigate the rapids that determines your success.

One final note about negative emotions: We’ve all heard that emotions are infectious. “Enthusiasm is contagious!” is an oft-cited notion. Well, the research is in. Scientists now say that negative emotions are actually more contagious than positive ones. So induce them judiciously!

Emotional Objectives

It’s time to get strategic and purposeful about how you plan on using emotions on your journey to yes. What emotions could you create? What emotions should you create, so that you can do the right thing for all involved? Here are seven emotional objectives to consider when building your case to persuade or dissuade.

- Provoke, by causing a reaction, especially an angry one.

- Inspire, by giving people hope or a reason to agree with you.

- Invoke, by enabling someone to see a particular image in his or her mind.

- Awaken, by making someone experience a new feeling or emotion.

- Arouse, by exciting someone with ideas or possibilities.

- Touch, by generating a sad or sympathetic emotion.

- Ignite, by invoking a feeling of success or accomplishment.

Building one or more of these emotional strategies into your business case will materially improve your chances of yes success.

The Physical Impact of Emotions

Emotions have been studied in almost every way imaginable. Scientists have scrupulously examined and interpreted voice-pitch characteristics, facial expressions, color choices, and so forth. Biological testing of the brain, fingertips, and saliva proves that as emotions measurably change, so does that individual’s physiology. In one United Kingdom study reported by the Washington Times in 2008, test subjects, particularly women, experienced an increase of testosterone in their saliva after being exposed to high-performance sports-car racing.

You’re probably not comfortable asking your coworkers to slide into an MRI machine or requesting permission to swab a client’s tongue, but there are still several ways to measure the emotional appeal of your case. They are the very same qualitative measures that we discussed earlier in this chapter.

Synthesizing Quantitative and Qualitative Justifications

Scenarios constantly shift along the corporate landscape, thanks to the vagaries of competitive action, government regulation, demographic change, globalization, and technological improvements (and obsolescence). Those individuals and organizations solely focused on quantitative arguments undermine qualitative arguments. But fear not; the emotional pull will prevail—even though it might involve taking a risk.

Risk involves ample degrees of probability and seriousness. Probability simply means how likely an event is to occur. Seriousness means how detrimental it will be to your situation if it does. By using these two simple, yet powerful, indexes, you can reduce the perceived risk and sometimes completely vitiate it. “Risk” as a concept can be deafening, but probability and seriousness—two quantitative tools you can bring to bear—often reduce the roar to mere background sounds.

For example, you may favor the recall of a product your customers are complaining about. However, you also might meet resistance among colleagues who claim that a recall announcement on one product would cause customers to request refunds for or fixes to other products—even though there is nothing wrong with those products. It is a dilemma, for sure, but you will win the day if you point out that the probability of more people wanting a replacement of the product in question is high, and furthermore that the seriousness of this approach is low, because there are ample stockpiles of the product, shipping can be done in bulk, and the company has sufficient cash reserves to support the proactive gesture. With no recall, however, the probability is high that adverse stories about the product in the media could affect sales of your company’s other goods, the federal government might launch an investigation, and lawsuits (both individual and class action) would be filed.

Consider the plight of automaker GM, under investigation in 2014 by the U.S. House Energy and Commerce Committee for taking more than a decade to recall 2.6 million vehicles with a defective ignition switch that allowed the car to shut off while being driven. The case propelled GM into a public relations nightmare, with company CEO Mary Barra testifying in very public appearances on Capitol Hill. You wouldn’t want to be in her shoes! Similarly, the degree of seriousness if your company chose not to recall the faulty product could include a monumental financial burden, the undermining of future product launches, and destruction of company credibility with investors.

Once again, you can see the synergies between quantitative and qualitative justification. The key: Use the power of emotion to grab attention for your argument; then augment your position with a logical case that will reassure doubters.

Building a Bulletproof Argument

Ultimately, we’re talking about creating both real and hypothetical case studies to prove a point. (Lawyers regularly do this, defending clients with “hypotheticals” to test the response of the prosecution.) To best convince others that your emotional case is relevant and powerful, consider these techniques:

- Draw from other industries by demonstrating how and when your idea has worked elsewhere and why it’s likely to work here. Show precedent (another thing that the law relies on heavily).

- Leverage contemporary issues. For example, you can suggest that the hoopla and distraction of Y2K was completely unwarranted, or that the creation of a strategic petroleum reserve was an act of sheer genius. What other contemporary issues can help you state your case?

- Provide examples that support why quick action is necessary or a more measured approach is appropriate. Remember “Weapons of Mass Destruction” and the war that resulted?

- Create “positional critical mass.” In other words, focus your early arguments on the movers and shakers, champions and avatars, who can best rally support for your position. It also helps when formal (hierarchical) and informal individuals (popular colleagues) support the position you espouse.

- Cite external experts (living and deceased) who can be leveraged to help cut through uncertainty. If I were attempting to persuade about technology, I’d cite Walt Mossberg, former Wall Street Journal columnist and creator of the popular conference D: All Things Digital; if my persuasion priority involved organizational strategy, I’d reference the late management consultant Peter Drucker.

- Provide opportunities for validation and verification. Present the metrics (quantitative help, once again) that will justify and validate your persuasion priority. For example, if you have 20 percent more clients six months from now than you do today, you’ll know your organization’s referral initiative will have been successful.

- Argue against yourself. People routinely write books that span both sides of an issue. Academic debating requires the ability to take either side of an issue and prove or disprove it. Make the anticipated arguments against your own case and rebut them, so that you’re prepared for the crucible. (In the law, this is called a “mock court.”)

One of the reasons I’ve deliberately used legal comparisons in this chapter on quantitative and qualitative reasoning, logic and emotion, is that the law is generally considered to be black and white. In reality, it consists of varying shades of gray. If that weren’t the case, why would we need judges and juries?

Every persuasive argument contains both quantitative and qualitative aspects. Not only can’t you afford to omit either dynamic, but you must appreciate the supporting role each plays for the other, as I’ve attempted to depict here. Mastering a synthesis of the two components will place you far ahead of the other persuaders—both those at the table and those down the block.

TARGET INTELLIGENCE

Now that you have a clearer sense for how you’re going to articulate your argument, let’s briefly return to the topic first introduced in Chapter 3—namely, your specific target. The primary rule of communication is “know your audience.” To maximize the chances that your persuasive efforts will be successful, you need not only to have an airtight pitch, but also to know key facts about the person to whom you’re pitching it.

What You Need to Know

There are three key categories to explore: personal information, preferences, and parameters. You won’t need to provide every detail for each category, but the more information you have, the better your chances of persuasion success will be. You’ll also be amazed at what you’ll learn.

So let’s begin: What do you know about your target?

Personal Information

- Professional objectives: These goals are important to a person’s business or career, which may involve status in a hierarchical structure, entrepreneurialism, or business ownership.

- Personal agendas: These goals involve family, friends, hobbies, travel, recreation, civic and service involvement, religious commitments, and self-development.

- Emotional intensity: This comes into play if a persuasion situation also involves a personal relationship, a belief that goes beyond intellectual evaluations, or commitment over compliance. Think of emotional intensity as the volume knob on a Marshall half stack, not the on/off switch. You can turn it up or down, depending on your needs.

- Personality considerations: Is there a style clash between your personality and that of your target? Is his Driving, Expressive, Amiable, or Analytical tendency (see page 49) blocking your efforts?

- Gender or generational differences: Are you two potentially out of sync because of behavior tendencies influenced by gender? Are generational differences creating a stone wall between you?

- Organizational influence: What is your target’s organizational horsepower?

- Publicly stated perspective on a given issue: This can include conversations, written communication, the championing of or opposition to similar issues, role as a stakeholder, and experience with the given situation.

- Trust level: What is the degree of trust shared between you and your target? Think of your personal history with the target, respect given and shown, mutual obligations, favors supplied, and reciprocal support.

Preferences

- Communication: Does your target prefer to communicate with you and others via email, phone, or text message?

- Data: Some people want all the information; others just want the executive summary. Some people like to study the stats; others like to hear the story. How does your target prefer her information?

- Work: Does he approach problem solving in a particular way? Does she have a go-to person? Does he often resort to cutting expenses or sales promotions? Does she exhibit behaviors that may impede your path to yes?

- Interpersonal: Examine your target’s advisers, peers, and sources of influence. Does your target have any exceptionally positive or unusually strained relationships? Also evaluate the probability of whether she will act independently or succumb to peer pressure.

Parameters

- Approval authority: This usually relates to economics, budgets, and the ability to secure funding by attracting donors or underwriters. (Note: Knowing this detail is crucial when dealing with targets in nonprofit organizations.)

- Budget jurisdiction: This relates to your target’s ability to make unilateral decisions, control timing in the budget process, determine ROI considerations, change priorities, and allocate discretionary funds.

- Time constraints: Consider the deadlines you and your target are under, the magnitude of what needs to be accomplished once agreement is reached, and the hours/days/months/years it will take to make the concept of the ask a reality.

- Issue expertise: This may involve credibility, history in this and similar circumstances, ability to research and study the issue, and public statements.

You may wish to add or amend categories. My point is that in order to define your target and the likelihood of persuasion, you need intelligence—not brain smarts, but what the government would call “intel.” I choose not to think of this as “competitive intelligence,” because the target isn’t necessarily in a competitive position (at least we should hope not). But the target is in a questionable position, insofar as how amenable that individual might be to your persuasive charms.

As humans, we rely on hearsay, body language, or visceral reaction for information. However, keep in mind that perception biases can mislead you. You’re better off beginning with a tabula rasa, or a blank slate, which you can fill with logical answers to intelligent questions in relevant categories. Don’t guess or simply rely on what you’ve always believed. Often, what you’ve perceived about others is not accurate and is sometimes antithetical to a particular person’s actual positions.

How to Get the Intel

It’s easy to say what to do, but the larger question is how to do it. Here are seven ways to gather evidence:

- Be present. When you’re attending meetings, working with others, or engaging in “hall chat,” try not to be consumed with your own tasks and agenda. These are key times to discover crucial clues that can help you find yes more often.

- Learn to watch and listen. What someone says and how that person says it can tell you a lot. You know your target’s hierarchical rank, but how carefully are you really listening to him? Pay attention to the inflection, tone, and degree of passion with which your target is communicating. How close is he already to your position on the issue? Be alert to the reality of the moment.

- Review applicable internal and external information. Think about the conventions, beliefs, protocols, and values people employ to govern their actions. Have conversations, not interrogations. Subtlety is an art form: Rather than say, “What do you know about the organizational politics regarding this project in marketing?” try, “Do you think the new project will be a tough sell to marketing?”

- Use the FORM model for conversations. In other words, bring up “Family,” “Occupation,” “Recreation,” and “Motivation” in conversations with your target. (“Tell me about your family. What do you like best about your occupation? What do you do for recreation? What’s your motivation for working on this project?”)

- Master the fine art of secret polling. Once people make their opinions known, they are loath to change them. That’s why it’s far easier to change the mind of someone who hasn’t yet made a public statement. In jury deliberations, a foreperson sometimes asks fellow jurors to state guilty or not guilty verdicts anonymously on pieces of paper; this is known as “secret polling,” and it is an effective way of revealing early opinions without forcing anyone to make a public commitment. The takeaway: Attempt to find positions privately without demanding, or even innocently inducing, a public declaration.

- Practice convergent validity. Don’t believe anything until you’ve obtained three pieces of evidence to support it. The following Sufi parable will help put this action into context: Three blind wanderers encountered an elephant in the jungle. “What have we here?” they exclaimed together. The first man, standing alongside the great beast, said, “It’s like a wall.” The second, who was holding one of the legs, replied, “No, it’s like a tree trunk.” And the third, tangling with the trunk, said, “I don’t know what you two are talking about, but this thing is like a snake.” Bridging all three perspectives brings the wanderers (and you) closer to the truth.

- Use the “nod quad.” The following four questions help you hear yes in almost any evidence-gathering situation, so I call them the “nod quad.” You won’t always use all of them, or use them in any particular sequence, but put these in your pocket and pull them out, as needed, to help you find the information you need:

- How much organizational agreement is there about the challenges we’re facing as a company?

- When you say _______ (time, money, risk, resistance), what specifically do you mean?

- What are you most excited about in your world right now?

- Do you think _______ (this proposal, this initiative, this idea) will be a tough sell in _______ (marketing, legal, research)?

The more significant your request, the more careful your intel gathering should be. When it comes to major projects, issues near and dear to your value system, and asks important to your career, you can’t afford to do anything less than engage in some serious quantitative and qualitative reasoning. People who are “natural” persuaders already go through this kind of process automatically and viscerally, without much conscious effort. Call it “unconscious competency.” You can get there, too.

Chapter 4 Persuasion Points

- Recognize that quantitative factors are often the default factors in a persuasive situation.

- Master the fundamental business measures and calculations that most frequently arise in meetings and discussions.

- Acquire assistance, if necessary, in arcane financial issues so that you can discuss them authoritatively.

- Be aware that, while logic prompts thinking, emotion propels acting.

- Learn to establish visceral, compelling arguments as they relate to important company considerations.

- Use quantitative facts to provide boundaries and understanding for “softer” issues and initiatives.

- Focus on the influencing power of risk. Articulate risk according to probability and seriousness, both for your position and the opposition’s, and ensure that yours is “safer.”

- Always focus on your target’s self-interests and emotional needs; that way, he will always perceive the advantage to be his.

- Remember that gathering data about your target is an essential step in achieving your persuasive priority.