CHAPTER 5

The Credibility Crucible

How You Get It, Why You Lose It, and How You Win It Back

Regardless of what line of business you’re in, every organization, every department, every team has at least one person whom everybody trusts. When that person takes on a project, it’s done well, on time, and on budget. He gives you advice? It’s solid. She provides data? It’s accurate. These are the people who get things done. And these are the people who hear yes more often.

In short, they possess the secret to persuasion success: killer credibility. The dictionary defines credibility as “the quality of being convincing or believable.” I define it with one word: essential. Throughout your career, your credibility will be tested. All the time.

Easy to lose and tough to build, credibility ranks as one of the primary characteristics of a successful and professional persuader. A basic determination of credibility can be found in the following descriptors:

- You do what you say you’re going to do.

- Your information is accurate and unbiased.

- You’re not prone to exaggeration or hyperbole.

- You admit when you’re wrong and accept blame.

- You share the credit when successful.

- Your word is your bond.

The key question is this: What do people say about you when you’re not in the room?

ASSESSING YOUR CREDIBILITY

Let’s consider two levels, or planes, on which your persuasion credibility operates. The first plane: You have either high credibility or low credibility. Easy enough. But keep in mind that there’s a difference between an event and a trend. Something that happens once is an event; three times is a trend. One success doesn’t make you a rock star, and one mistake doesn’t make you a failure. It’s the body of work that counts.

The second plane: Are you—your skills, your abilities, and your results—personally known by your target? If you’ve worked with your target, you’re known. Simple as that. If he sees you in the hallway and can call you by name, you’re known. If you haven’t worked with your target in the past, you’re unknown. She may know of you, but that doesn’t count.

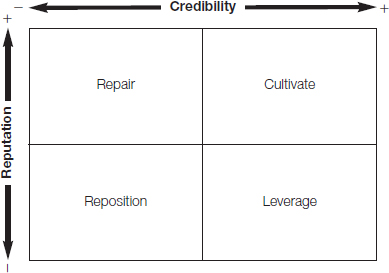

The credibility quadrants shown in Figure 5-1 will enable you to consider which quadrant you might fall into with a particular target, and what action needs to be taken as a result.

Known Reputation/Low Credibility

Here you have to repair your reputation, for whatever reason (and it could be situations outside your control). Start small. Make the call. Apologize. And from that point forward, promise yourself that you won’t let this particular mistake happen again. Everybody makes mistakes. High earners learn from them.

Here’s an example: When the on-demand streaming and DVD-bymail service Netflix announced a split in 2011, with the DVD piece of its business relaunching as Qwikster, customers went nuts; they were furious with the move, which came on the heels of a price increase. Netflix CEO Reed Hastings took to Netflix’s blog. “I messed up,” he wrote. “I owe everyone an explanation.” Less than a month later, he blogged again, announcing the quick end of Qwikster. Today, Netflix has more than 44 million subscribers—proving that customers (and coworkers) are usually a pretty understanding bunch if you keep them in the loop.

If you’re in a comparable predicament and you fail to act as Hastings did, you risk having others see you as disingenuous or dishonest. Here are other ways to remedy a similar situation:

- Acknowledge prior setbacks. Don’t pretend defeats were victories and luck was talent.

- Accept responsibility. Share credit but corner the market on blame.

- Request guidance. Openly reach out for ideas and courses of action that restore credibility.

Unknown Reputation/Low Credibility

Sometimes a bad reputation precedes you. And, not infrequently, it’s the result of guilt by association. Perhaps you work in the human resources department, and in your organization, HR doesn’t have the most upstanding reputation. So you’re already down a notch before you enter a room.

In that case, it’s essential to reposition yourself. Don’t be defensive. Don’t have a chip on your shoulder. Don’t look for a fight. Instead, use facts, stats, and evidence to the contrary to show why the bad rap on your department might not be accurate. Here are some ways to do that:

- Use third-party information to help others understand the situations that created the negative impression.

- Make reasonable, verifiable statements about your background and intent. Put people at ease with facts.

- Determine your target’s values, as well as his personality traits and how he processes information. Cater your strategies, conversations, and behavior appropriately.

Rarely do people have Paul-on-the-road-to-Damascus epiphanies, but as you present your target with evidence that counters the original, less-than-optimal impression, you will start to reshape, reframe, and reposition your reputation.

Unknown Reputation/High Credibility

You and your abilities might be unknown, but you still pack high credibility, either by significant word of mouth about you or by your connection to a successful initiative. Well done. You have successfully built a reputation of being knowledgeable and dependable. So now what? Leverage your position! Your perceived value—your “stock price,” as it were—will never be higher. Here are ways to make your influence work for you:

- Use this position to attain additional success. Build on what you’ve achieved by going after more projects, more clients, and more opportunities to hear yes.

- Negotiate terms for future deals that work to your advantage. Take into consideration the accountabilities, the workload, the time frames, and, most important, the price. You may never be in this position again!

- Make sure that you deliver on your newly made promises. This brings us to our fourth, and final, quadrant.

Known Reputation/High Credibility

If people know you, have worked with you, and think highly of you and your abilities, congratulations! You’ve arrived at the mountaintop. This is where people strive to be—and now it is up to you to cultivate this position.

Being in this quadrant means that people trust your input and your performance so much that they ask for and heed your advice wholeheartedly. Steve Jobs had that kind of pull. He created a demographic of computer consumers who wait in half-mile-long lines for an entire day to purchase a product they’ve never touched or even seen up close—all because it has the Apple logo on it.

But beware: Customer and colleague relationships are precious and should never be taken advantage of by abusing credibility to sell unnecessary, unwanted, or low-quality items. Remember Apple’s shortlived MobileMe subscription service? That was a disaster, and Jobs had the integrity to admit it. And, as with Netflix’s Hastings, customers forgave him. The best ways to capitalize on this quadrant are to:

- Ensure that your actions match your reputation. Don’t allow for cognitive dissonance. Be consistent.

- Utilize the trust that is automatically bestowed.

- Be mindful of your actual performance. You can easily lose the lofty perch because you’re so visible and observed.

- Be assertive but not arrogant. Make achievements visible but not obnoxious. You can afford to be modest.

- Set reasonable expectations for the future. You want a solid foundation that you can build upon, not a house of cards.

- Be sensitive to differing perspectives and people assessing your accomplishments through their own lenses.

Know your quadrants, and develop the skills and strategies required to work your way toward being a highly credible, known force. Credibility is that important.

THREE COMPONENTS OF CREDIBILITY

Credibility cannot be achieved if you don’t possess the following three attributes: expertise, track record, and respect. You can get by with two of those three, but it’s going to be tough. So go for the hat trick.

Expertise

Expertise means that you actually comport yourself as an expert. Experts’ opinions are believed and sought; they are not generally subject to quibbles or arguments. No one ever walked up to Peter Drucker and challenged his thinking about management strategy.

You gain expertise through experiences, education, observations, and boldly moving on from both your victories and your defeats. It’s fine to be defeated in a good cause if you learn from it. After all, you hone your skills through continual, real-world application. It’s often said that saints engage in introspection, while sinners run the world. Think about that.

In today’s world, which is rapidly changing through globalization and our ever-intensifying use of technology, expertise necessitates engaging in an ongoing quest, not maintaining a static position. How do you know you’re an “expert”? Because people cite you, quote you, defer to you, ask your opinion, and use you as the standard—even if all that happens only within your own organization.

Track Record

Nothing succeeds in promoting credibility like results that others can see, touch, feel, hear, and smell. In other words, don’t just talk the talk; walk the walk. Track records don’t require uniform and unblemished successes. In fact, showing variation is preferable. The idea is to constantly improve. The best batters in baseball, on average, get a hit only once in every three at bats.

The key idea regarding looking back on your successes and failures is to build on your strengths. We spend too much time evaluating defeats (performing postmortems) and correcting weaknesses. Determine how and why you were successful, and seek to replicate that success. If you do, weaknesses will naturally atrophy. By the way, if you look at my suggestions for each of the quadrants above, you’ll note that acknowledging your “defeats” is an integral part of building your credibility.

Respect

By “respect,” I mean not merely affection. No one respects people who can win only if someone else loses, or who see life as a zero-sum game. You don’t have to like everyone, but you do have to remain civil. When you share, you gain respect; you also gain respect when you accept responsibility, when you volunteer, and when you effectively negotiate and honestly resolve conflict. Engendering respect requires the savvy use of interpersonal skills. The ways in which you communicate with colleagues, associates, and clients play a large role in credibility and prove your ability (or inability) to create allies instead of adversaries.

An important factor in leveraging these three components is your willingness to coach others. Coaching builds your expertise, your track record, and your respect. It’s like “one-stop shopping.” As Yogi Bhajan, the late spiritual leader and entrepreneur who introduced kundalini yoga to the United States, once said: “If you want to learn something, read about it. If you want to understand something, write about it. If you want to master something, teach it.”

ACQUIRING, LOSING, AND REBUILDING CREDIBILITY

Once you’ve established credibility, there’s no guarantee you’ll hold on to it forever. Circumstances beyond your control (or of your own doing) can cause you to lose a little or a lot of credibility. When that happens, you must find a way to recoup those losses and come back stronger than ever. In this section, we’ll demonstrate behaviors that lead to various outcomes.

Four Ways to Build Credibility

Gaining credibility is easier than you might think. In fact, you might already have established a significant degree of credibility among your professional peers and not even know it. If you currently do any of the following, you’re well on your way to creating credibility confidence.

- Publicize your successes. Demonstrate your triumphs, relate your victories, recount your progresses—but don’t boast about them. And just because a success may be small doesn’t mean it isn’t worth noting or discussing. Nothing breeds like success—and it is more likely to breed if people know about it.

- Create a “rational future.” In other words, help people see a future that begins pragmatically in the present and develops logically and persuasively forward along a reasonable path. I observed Steve Ballmer in 2000 (after he succeeded Bill Gates as CEO) attempt to rally the troops at Microsoft’s 25th anniversary bash, and what he intended as a show of great energy and passion came across as almost berserk ravings (which is exactly what the press reported and the investors perceived). Ballmer retired from the company in early 2014 after 14 years at the helm.

- Become clearly accessible and accountable—or, to use contemporary jargon, “transparent.” I remember some college professors who held regular office hours and seemed genuinely happy to welcome students, and others who seemed to take wicked pleasure in ignoring their students. The former had far more credibility among students when it came to their opinions and critiques. After all, people are less likely to argue with an individual who is clearly available and responsible.

- Hang out with other credibility all-stars. Leadership coach Marshall Goldsmith says that in order to be a thought leader, you must surround yourself with other thought leaders. The same principle applies to credibility. Find people with impressive credibility credentials within your organization or community and align yourself with them. Learn from them and support them, and eventually you’ll become like them.

Four Ways to Lose Credibility

Only one condition is worse than not having credibility—having had credibility and losing it. Credibility lost is extremely hard to regain, so let’s look at the causes (with an eye toward preventing this from happening).

- Stop succeeding. If your success track record ends, so will your credibility. Either you will fail to make continuous progress and achieve victories, or you will continue to do so but no one will know.

- Deceive people. Most unethical conduct in corporations is committed for the organization’s gain, not one’s personal gain. But that doesn’t lessen the impact. “White lies” in business—unlike those in family situations, where the complete truth might significantly hurt a loved one—can be tolerated in very few situations. When someone knows that you’ve lied, that person immediately wonders what else you’ve been (or are or will be) lying about. And that, friends, throws your credibility over the edge of the cliff.

- Fail to share credit. That’s why I continue to emphasize accepting blame and sharing credit. It’s better to risk providing credit to even peripheral contributors than to fail to reward even one person.

- Allow your ego to become the size of a balloon in the Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade. If you think only of, about, and for yourself, that will become quickly apparent to those around you. You must demonstrate that you’re acting with others in mind via gestures of generosity that are clearly visible. A simple and public “thank you” often packs more punch than a reward handed over in the privacy of an office. There are reasons why the U.S. military puts medals on people in front of a lot of other people.

Can you return from credibility self-immolation? It’s tough, but yes. And when you do, you’ll be joining a club of famous people who came back from the abyss to reinvent their careers (and, in some cases, attain even higher heights), including Bill Clinton, Hugh Grant, Robert McNamara, Tiger Woods, and Jack Welch.

Ten Steps to Win Back Credibility

As chairman and CEO at General Electric for 20 years between 1981 and 2001, Jack Welch became known as “Neutron Jack,” because his oftendraconian decisions eliminated people while leaving buildings unscathed. However, when GE suffered a variety of public bruisings—scandals within the multinational corporation’s credit department that involved pricefixing with diamonds in South Africa and money-laundering and fraud in Israel—Welch unilaterally announced that henceforward managers were required not only to meet performance goals, but to do so within the company’s value system. Doing one or the other would be insufficient. In short order, a conglomerate that manufactured everything from lightbulbs to locomotives became a model company because Jack Welch had regained his, and his company’s, credibility.

Hugh Grant, after being caught with a prostitute in Los Angeles two weeks before the 1995 release of his first major studio film, Nine Months, regained credibility by following a totally different path: He went on The Tonight Show with Jay Leno, whereupon the host famously asked him, “What the hell were you thinking?” Grant’s response: “I think you know in life what’s a good thing to do and what’s a bad thing, and I did a bad thing. And there you have it.” He went on to become a successful leading man in Hollywood—in part, I’ll argue, because he admitted his mistake and blamed no one but himself. That’s one way to mend a credibility gap.

President Bill Clinton, another man whose moral temptations got the best of him, was impeached for his actions related to his inappropriate relationship with an intern and later for lying to Congress about his behavior. Today, he’s regarded as a consensus builder and a brilliant politician. Likewise, a great many people are once again cheering for Tiger Woods on every tee and green. So don’t feel as though you cannot regain trust and credibility. Here are 10 steps to put you back in good grace with colleagues and associates:

Step 1: Assess the damage. Try to understand what really occurred, factually and perceptively, that caused you to lose credibility. If you need objective help, don’t be afraid to ask others, because you can’t afford to underestimate the damage or assume it will pass with time. The damage O. J. Simpson did to his credibility did not pass with time.

Step 2: Admit your error. Honesty counts for a whole lot in business. As stated earlier, lies have no place in running an ethical operation. Lying about a mistake or passing the blame will only undo whatever credibility you’ve managed to hold on to.

Step 3: Learn the language of apology. As Netflix’s Hastings discovered, admitting a mistake or wrongdoing may not be enough. You need to understand the power of apologetic language. Sharing information about pending and completed decisions, apologizing for mistakes, and listening to and responding to concerns, questions, and comments are at the core of leadership credibility.

Step 4: Start rebuilding credibility with small steps. Engage a few people or groups at a time, focusing on low-key topics and noncontroversial issues. Make sure you deliver what you promise when you promise.

Step 5: Channel your inner Johnny Carson. Johnny Carson is one of my all-time favorite American entertainers. One of the best. When a guest would mention a current event or piece of knowledge outside Johnny’s realm, the host didn’t feign understanding, try to take over the conversation, or “one up” the guest. He simply said, “I did not know that.” That’s what I say now, and you should, too.

Step 6: Realize that credibility is a volume knob, not an on/off switch. It’s impossible to be “mostly pregnant,” but you can be “mostly credible.” Seek success, not perfection. Think of the needle registering on a gauge: You want it to keep rising, which represents strong and steady progress. It doesn’t need to be revving on the red line to be working properly.

Step 7: Remember that all things are relative. Nobody is asking you to be “the most credible” person ever at your job. You simply need to be credible. It doesn’t matter if you’re the most popular guy in the office or the best-liked gal in your department; so why strive to be the most credible? Such distinctions carry very little weight in most cases.

Step 8: Conduct conversations about your lapse. This will allow you to prove you’re in a better place now. Just don’t raise the issue incessantly. If you’re comfortable conversing about it, you’re going to make it a topic of conversation and not a cause célèbre.

Step 9: Allow some events to fade, especially if they’re minor. Don’t keep reminding people of every previous transgression. You may have been tipsy at an office party, but someone else probably drank a lot more.

Step 10: Shake it off. Don’t let mistakes undermine everything you do. Ignore the “doom loop” mentality of struggling with a credibility issue or an incident that serves only to further undermine your confidence and credibility. Let it go the way an athlete overcomes a minor injury. Don’t go running to the training room or, worse, admit yourself to the hospital.

How Don Imus Reengineered His Credibility

Don Imus has been a syndicated radio talk show host for more than three decades, the winner of four Marconi Awards, and a well-known media personality who always seemed to wear his signature cowboy hat. His show (also broadcast on TV in many markets) is irreverent, sarcastic, and ironic, while also being provocative and featuring members of Congress, famous authors, scientists, and celebrities.

In 2007, Imus and his producer, during the course of on-air banter, made incredibly inappropriate and racist remarks about the Rutgers University women’s basketball team. Reaction was swift and decisive. Imus was suspended, then fired—a 40-year career gone after 40 seconds of thoughtless, offensive comments. Even many of his stalwart supporters in the media failed to have his back.

What did Imus do with his newfound free time? He went on the apology circuit, embracing the media and even appearing on Al Sharpton’s radio show in New York, where he knew he’d be pummeled. He visited the Rutgers women’s basketball team. After six months, he returned to the airwaves with a larger syndicated network and achieved higher ratings than ever. Today, Imus is back on top. Sometimes he discusses his humongous error in judgment and expresses how much he regrets it. This makes Imus an excellent example of credibility rehabilitation.

THE BOTTOM LINE ON CREDIBILITY

Is credibility the shield to prevent bad things from ever happening to you? Of course not. We live in a what-have-you-done-for-me-lately world. An interviewer once asked Jerry Seinfeld if his television success had any positive impact on his stand-up act. “Yes, it buys me about five minutes,” the comedian replied. “After that, I’d better be funny.”

Same thing applies here. If you are perceived as being a credible individual, you get about a five-minute leeway. After that, you’d better be credible. Period.

Chapter 5 Persuasion Points

- Credibility is in the eye of the beholder; look through the other person’s lens.

- You can have high credibility, even as an “unknown.”

- Focus on expertise, track record, and respect.

- You can consciously build and nurture credibility.

- You also can recapture and rehabilitate credibility.

- Don’t seek perfection; seek progress.

- Some memories fade, which you should allow.

- Don’t make a bad situation worse by overthinking it.

- If Bill Clinton and Hugh Grant can rehabilitate their credibility, so can you.