CHAPTER 10

Yes Success

What to Do When Your Target Agrees (and Why Most People Don’t Get This Right)

We plan for objections and we plan for resistance; but we often don’t plan for success. This is a big mistake. Learning to handle this moment with panache will differentiate the Hall of Famers from the also-rans. This is because it is in the moment of yes that you can reassure your target that he or she has made a wise decision. And from there, you can begin to position yourself for even higher levels of persuasion success.

FIVE MOMENT-OF-YES DON’TS

When you hear yes, you’ve accomplished your objective. So don’t blow it by falling into one of the following five traps:

Don’t immediately reply with an incredulous “Really?” A response like that can erode any confidence you’ve already built in your target and have that person second-guessing his decision. You don’t want to appear gob-smacked that someone actually believes in your pitch. Sometimes, people seem so shocked at their own success that they inadvertently convey those thoughts to the target. They feel the need to say something, so they rush to fill the void in the conversation with a silly response.

So what should you say? “Excellent.” “Fantastic.” “Smart move.” Even silence is better than a dumbfounded, “Really?”

Don’t keep trying to make your case. Just stop.

My first car was a 1967 Dodge Dart, three-speed on a tree. (For you Millennials, that means a manual three-speed shifter on the steering column.) It was far from a new vehicle when I was driving it. If everything wasn’t just right, when I attempted to turn off the car the engine would sputter and run and sputter and run some more. Like a cockroach, the Dart wouldn’t stop—especially if I was on a date. During those times, I remember cringing with embarrassment and pleading with my Damsel from Detroit, “Please, just stop!” That’s what your persuaded target will be thinking, too.

Don’t review your target’s concerns. Occasionally, you might feel as if there needs to be one final review of all the problems you’ve solved, and you might be tempted so say something like this: “Okay, so as you know, with the new project time line, we should be able to complete the market analysis before we get the new additions to the field team in place, and before the new finance programs are approved. All of this is dependent on EPA approval of the new system.”

Yikes! Your point-by-point review has, all of a sudden, made your target nervous, which might make him renege on his commitment. Don’t feel obligated to act as if your target’s concerns are top of mind at this point. You’ve heard those concerns, the target still said yes, and now both of you can move forward.

- Don’t be unprepared. You can’t anticipate every eventuality, but you can plan for some. If, for example, a purchase order needs to be signed, have it with you and ready to go. If you need to call someone to issue a verbal authorization, have the contact’s name and number programmed into your phone. And for heaven’s sake, have a decent pen with you in case you need to write something down. Lack of preparation in the moment of yes could lead your target to second-guess the decision she’s just made and bring your credibility into question.

Don’t bask in the glow of your success. When I played baseball as a kid, I was pretty good with the bat. I still vividly remember hitting the ball solidly with my bat’s sweet spot and then standing with pride as that ball sailed into the outfield and over the fence. I did this frequently—enough so that my coach would intone, “It doesn’t mean anything if you don’t run.”

After your target says yes, hit the bases. Simply say, “Excellent. We better get to it.” And then start running!

Why Your Office Is the Ultimate Home-Court Advantage

As many readers know, I consider Robert Cialdini, author of Influence: The Psychology of Persuasion, to be the godfather of persuasion. His research, summarized in Chapter 2, laid the groundwork for much of how persuasion is practiced today. One of his studies compared patient compliance with the prescribed behavior dispensed by both physicians and physical therapists. As things turned out, patients followed their doctors’ orders, but not their physical therapists’.

When Cialdini evaluated the environments in which the directives were given, he observed that the doctors wore white coats and made their diagnoses and prescriptions in rooms whose walls were adorned with state licenses, medical school diplomas, and other validations of their qualifications. But while the physical therapists themselves possessed equally impressive qualifications, their physical surroundings tended not to tout their credentials, but rather to sport motivational posters (including at least one featuring a kitten, presumably clinging for her life and spouting, “Hang in there!”). Once the posters were replaced with licenses and diplomas, patient compliance increased significantly.

Meaningful credentials speak volumes. Display diplomas, awards, and other documents denoting serious achievement in your work space so targets can clearly see them. Doing so will help your target feel more comfortable about his decision to say yes to you.

FIVE MOMENT-OF-YES DOs

Just as you can clearly make missteps when you hear yes, there also are actions you can take that will help remove any trace of doubt your target may have left. Here they are:

- Immediately shake hands. I know it seems obvious, but you’d be shocked to realize how many people miss this important moment. Shaking hands is almost always the socially acceptable thing to do (though, in certain cultures, it’s a good idea to check—especially in male-to-female agreements) for everything from meeting and greeting to saying thank-you and offering congratulations. A handshake also signals the completion of an agreement. (In the Middle Ages, it also demonstrated that the other person was not holding a concealed weapon!) Even if I’ve worked with a person for years, on a big agreement, I always shake hands to affirm the commitment.

- Offer a reinforcing comment. While shaking hands, it’s critical to also offer some sort of agreement-reinforcing comment: “This is going to be an exciting project.” “We will do great work together.” “Here’s to accomplishing important work.” Avoid statements such as “Well, here’s hoping it works!” or “Thank you for the opportunity; I hope I make you proud.” The objective here is to fill your target with confidence, not initiate buyer’s remorse or demonstrate that your pitching skills are stronger than your confidence.

Give a “next steps” overview. Here you want to be absolutely clear on what will happen next: “Okay, so I’ll work with the legal department this afternoon to put the final details into an agreement. You’ll be deciding which budgets to use. And we’ll collaborate on the project’s announcement this afternoon. By this time tomorrow, we’ll be up and running.”

In other words, determine who will handle the purchase order. Who will draft the agreement. Who is communicating what to others. Much like the martial art of aikido, you want to use the natural momentum of the agreement to solidify things and get them moving.

Make sure your target takes action. In the example above, the target is given next-step responsibilities. That is intentional. Sometimes in the moment of yes, persuaders are so relieved to receive agreement that they take the focus on accountability off the target. Don’t create a “sit back and relax” experience for your target. You want her to be required to take action. Your target should be committed to the decision, not merely compliant. The only way that will happen is if she has something to do.

The balancing act here is in not making that action too onerous. It shouldn’t require the cognitive strain of quantum physics or the physical equivalent of shoveling rocks. Suggested activities: Make a phone call, provide a signature, send an email, review a document. Set something you and your target can agree on immediately, then schedule a follow-up session.

Go public. As I wrote in the beginning of this book, no one wants to be considered a hypocrite. The majority of people want to perform consistently with their publicly stated ideas and positions. So it behooves you to nudge your target to go public. This can take the form of letting just a few people around the lunch table know about the agreement to distributing a company-wide memo to alerting the local and national media. Going public makes that yes official by naming those accountable and broadcasting the commitment.

If the Situation Were Reversed . . .

There are moments of extreme power in human exchanges; instances where influence can be wielded for the good of both parties. One of these moments is when someone says, “Thank you.” But we often handle these opportunities poorly.

A client thanks you for your help and you say, “No problem. Would have done it for anyone.” A coworker thanks you for your assistance and you say, “Sure, it was easy.” A supplier sends a note of appreciation and you leave it at that.

Not only are these relationships not furthered, but we may have actually damaged them by these responses. Making someone feel unappreciated, incompetent, or not worthy of a response is a surefire way not to increase your influence.

Another potential problem is when the exchange is framed such that the other party feels they’ve just done a favor for Vito Corleone (“Someday I may call upon you to do a service for me.”) Saying things like, “And now you owe me one” is an excellent way to build animosity and opposition. So how can you avoid making this mistake? Be prepared to use powerful language. That’s how. Robert Cialdini, author of the seminal work Influence: The Psychology of Persuasion, suggests: “My pleasure, because I know if the situation were reversed, you would have done the same for me!”

Watch as the other person nods furiously in agreement, and you have now used language to expertly and subtly earn a “chit,” which is an informal influence credit. Practice this until you can use this (or other similar language) to create compelling yet conversational exchanges.

CREATING PERPETUAL YES

After the initial joy fades from that long-anticipated moment of yes, you’re faced with the aftermath. What now? The key to long-term career success is not just obtaining agreement; it’s about obtaining agreement again, and again, and again—creating perpetual yes.

You can do a number of things to ensure this cycle of yes, beginning with the obvious: Perform outstanding work. Nothing gets to yes again and again like past success. As I’ve reiterated throughout this book, my definition of persuasion is “ethically winning the heart and mind of your target”—not “getting one over” on someone. Persuasion is about allowing your brightest arguments to illuminate the path for others.

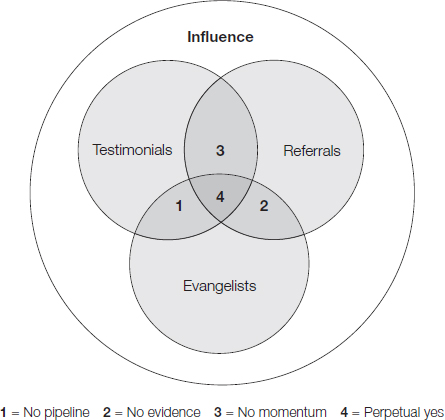

Now that you’ve succeeded with one persuasion priority, get ready to create perpetual yes by understanding how to create, acquire, and leverage testimonials, referrals, and personal persuasion evangelists. A testimonial is static evidence of success (a letter, email, or recording), a referral is someone who comes to you for a particular reason because someone else specifically recommended you, and a personal evangelist is someone who actively sings your praises. You’ll need all three if you want to create what I refer to as a “career of perpetual yes.”

As shown in Figure 10-1, if you have testimonials and evangelists without referrals, you won’t have a pipeline for cool projects and opportunities. If you have referrals and evangelists but no testimonials, you won’t have any evidence of your success. If you have testimonials and referrals without evangelists, you’ll lack momentum. Build your rock-star career with all three.

Getting Testimonials

A testimonial is an endorsement of either you or your team. It can speak to character, skill, or result, and it can be a letter, a video, or a voice recording. Even a personal reference counts as a testimonial. I’ve never met anyone who said testimonials don’t matter. Then why don’t more people go out and get them? The best persuaders are constantly accumulating testimonials, like trophies, for projects well done.

The best time to capture a testimonial is when that window of opportunity opens. In social exchanges, that might be when someone compliments you or thanks you. Shyness won’t help you here. Let’s say your happy target shakes your hand, smiles, and says, “You’ve done a great job on this project. You did everything we talked about and got great results we needed. Thank you!” If you respond with a “Happy to help” or a plain and boring “You’re welcome,” you’re missing a huge opportunity.

You’re target is pleased, so now is the time to ask him for a testimonial. He’s more likely to say yes now than at any time in the future. But people don’t ask, because they don’t know how, they consider doing so to be rude, or they fear rejection.

When requesting a testimonial, I suggest something like this: “Happy to help. We’re glad the project turned out so well. We’re always trying to spread the good news of what we’re doing in the sales division. Would you take what you’ve just told me and put it in a quick email message so I can show others how pleased you are?”

Get testimonials any way you can. I’ll take a testimonial via text message, email, voice mail message, or iPhone video. Sometimes, your happy target might even say, “Write something up, and I’ll give it a look.” Done! Video is most compelling, but I will do whatever the other person prefers in the moment. Don’t be bashful about pulling out your camera or phone right there and shooting 30 seconds of spontaneous support! Don’t fear rejection, either. You can’t walk away with less than you walked in with! You’re simply trying to create leverage to further your goals.

The greatest aspect of testimonials is that they can be used all the time, with both internal and external clients, buyers, and targets. Drop them into conversation with others: “This project is important, and we’re confident about our projections. I know you know Anne Emerich in product development. We worked with her on a big project last quarter. She used the word astonished when she described how close our projected return matched the projection.”

Pull pithy quotes and add them to your email signature, too—“the best marketer in Dallas!”—and provide references to them in your proposal cover letters and other materials.

Leveraging Referrals

While testimonials are static statements for a job well done, a referral is an introduction to another potential client or customer. One person says to another, “You should really talk to Tom. He did terrific work on our project, and he might be able to help you.”

The next best thing to someone witnessing your outstanding performance is having a trusted colleague tell someone else about that outstanding performance. Call them referrals, call them introductions, call them networking opportunities. Whatever. Just take advantage of them.

Referrals will help your persuasion efforts because they provide your target with a “warm” contact. You’re a friend of a friend, a welcome visitor, a known entity. This offers instant credibility and removes the time and effort required to “prove” yourself and your credentials or ideas. Your target is immediately and seamlessly involved.

Yet, like getting testimonials, many people don’t leverage referrals. I call it “referral reluctance.” They don’t want to imperil a new relationship and are more concerned with being liked than being respected, with gaining affiliation instead of gaining an objective. They also don’t want to sound like a salesperson. They feel, inexplicably, that they are asking for something instead of contributing something, trying to take instead of give. Sometimes, people feel as though they will put the other person in an awkward position. In those cases, their sympathy outweighs their empathy.

In addition, there exists a phenomenon called “referral deferral,” whereby your persuaded target doesn’t want to sound as though he is pushing your business toward others. In some cases, that target may have been “burned” before when making what turned out to be a bad referral to a friend. Or perhaps, people don’t like when they are put in a similar position. Other possible reasons for referral deferral include not wanting others to think they are part of a manipulative action, not knowing what to say, lacking trust, or simply possessing an innate cynicism that precludes them from reaching out to colleagues and peers.

You can help overcome referral reluctance and deferral by establishing a good rapport early on. Securing referrals and introductions shouldn’t be an ambush. So, if you’re working with someone on a project and think you’d like to leverage that person for future referrals and introductions, simply say something like, “My objective is to make you so deliriously happy that you’ll want to tell others about our great work.” This will make you memorable, because a lot of people don’t make such bold statements. “Deliriously happy” is compelling language, like Babe Ruth calling his shot.

I like to end such conversations with a quick confirming question: “Fair enough?” “Sound good?” Now your target has gone on record and will be more inclined to follow through on that referral, because he promised he would.

Obtaining Referrals in the First Place. Timing, in business and just about anything else, is everything. Some moments are better than others when asking for a referral. You don’t want to ask too early in the project, because you may not have delivered or begun to show results yet. That would be like proposing marriage on the first date. You also don’t want to wait too long, because, no matter how well you’ve performed on an assignment, enthusiasm cools and memory fades.

The two best times?

- When your target has made a significant, mid-project positive comment. For instance: “Working with you is so easy!” Now, that is an opportune time, because I have never seen a project go smoothly the entire time. There always seems to be a midcourse correction required or a misunderstanding or an argument at some point during the process. So take advantage of propitious moments when you can.

- When your target has indicated excitement and you sense you can capitalize on it. This might be during your project wrap-up, while reviewing positive results, or whenever you hear such trigger terms as “excellent,” “pleased,” “satisfied,” “terrific,” and the ever-popular “awesome” and “amazing.”

Again, as with testimonials, asking for referrals requires charm and savvy: “We’re thrilled you’re so pleased with the way things went. Remember, our goal was to make you deliriously happy. Who else in the organization could you recommend who might benefit from working with us?” (Here is where terms like “recommend,” “suggest,” and “advise” really pay off.)

Maintaining the Referral Relationship. After receiving a referral, don’t overlook the importance of following up with the referring party. Always keep that person in the loop. That way, he or she can help if the third party isn’t immediately responsive. This will additionally motivate the referrer to provide you with more contacts and support. After all, the referring party will score some points with his or her sources, too.

Creating Personal Evangelists

An evangelist, of course, is someone who promulgates something enthusiastically. There already exist religion evangelists, technology evangelists, and brand evangelists. Now I’m suggesting you create personal evangelists: people who sing your praises and attempt to convert others to, well, you. Here are five ways to do just that:

- Be a rebel with a cause. In a research paper published in the Journal of Consumer Research, Caleb Warren and Margaret C. Campbell define cool as: “a subjective, positive trait perceived in people, brands, products, and trends that are autonomous in an appropriate way.” The researchers cited a 1984 Apple advertisement as a prime example. In essence, it communicated that “You have a choice” and then implored “Don’t buy IBM.” Note: The ad didn’t say, “Burn IBM’s headquarters to the ground.” So be “out there”—but with boundaries.

- Don’t try to appeal to everyone. If you want true staying power, you can’t appeal to everyone. Yep. You read that right. The rock band KISS, an ongoing entity for more than 40 years, with some 80 million albums sold, was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 2014. One of the main reasons the band made it that far is because it created a rabid group of evangelists known as the KISS Army, which packed tremendous staying power. These people are devoted fans. Lead vocalist Paul Stanley said it best: “Either love us or hate us. If you’re in the middle, get out.”

- Take care of those who support you. Lessons also can be learned from another rock band, albeit one with a much different musical style than KISS. The Grateful Dead’s evangelists, known collectively as “Deadheads,” demonstrate the power of the people in almost everything they do. For example, while the Grateful Dead buck convention in many ways, it’s still shocking to think that the band has allowed Deadheads to record their shows for free and actively encouraged bootlegging of their music for decades. Why? Because it endears the band to the fans. Reciprocity, anyone? (I’d love to see Justin Bieber’s management team pitch that idea. Or, for that matter, KISS.)

- Be elegant. Steve Jobs was so fanatical about design that he added costs and increased development time by raving about the importance of the aesthetic design of the circuitry found inside Apple products. Everything you do should be as elegant as the circuitry in your MacBook Air. Earlier, we covered the importance of creating sartorial persuasion by dressing sharply and pulling your office together—both of which can do big things for your persuasion powers. Now apply that approach to emails you send, documents you create, and PowerPoint presentations you deliver. Make sure everything has what graphic designers used to call “eye-wash”: Your stuff not only has to be good; it has to look good, too.

Be like Billy. And speaking of speaking, I mean speak like actual evangelist Billy Graham. I asked a person whose opinion I respected who was the greatest speaker he’d ever heard? His reply: “Billy Graham. And I’m agnostic!”

Speaking is one of the most effective ways to create personal evangelists. Know your topic, engage your crowd, and deliver your message with enthusiasm. Whether you should mimic Billy Graham’s style or content is up for debate, but exceptional speaking skills can create a tent-revival atmosphere around you and your persuasion priorities.

If you really want your career to race toward success like a Top Fuel dragster, you need to carefully prepare for success.

Chapter 10 Persuasion Points

- Be prepared to exploit success when people agree.

- Know when to stop “selling” and begin “sowing.”

- Use language to propel discussions and actions.

- Exude confidence and enthusiasm, both of which are infectious.

- Nothing gets to yes again and again like past success.

- Never fail to seek testimonials and referrals.

- Find ways to overcome “referral reluctance” and “referral deferral.”

- Choreograph, orchestrate, and set the stage to hear perpetual yes.