CHAPTER 7

Persuasive Processes

A Five-Step Sequence to Yes

Now it’s time for some power calculations. Ready? Remember the Persuasion Equation, which I laid out for you in the Introduction? This is the combination of factors that will add up to your persuasion success. To recap:

(A Great Business Case + Your Outstanding Credibility + Compelling Language) × Intelligent Process = Yes Success

The last three chapters have, in essence, walked you through how to create a great business case, spit shine your credibility, and hone your power language skills. Now it’s time to master the persuasive process.

To do this, I’m going to reference another—albeit just slightly more famous—formula: Albert Einstein’s Theory of Relativity. Yes, that’s right: E = MC2. Well, we know the formula, but I’ll be smacked if I can find someone who can explain it to me. Luckily, that’s not on today’s agenda. I bring up Einstein only by way of presenting another, similarly structured, formula, one that governs persuasion success: Yes = E2F3.

In short, Yes = E2F3 is defined as follows: You get to yes by Engaging your target, Exploring the issue, Forming (and framing) possible options, Finessing any white water, and Finalizing (and formalizing) the decision. While this formula might seem a little long, it will prove to be a vital component of your overall Persuasion Equation. That’s why we’re going to spend this chapter walking through each and every step of it together.

THE PRINCIPLE OF NUDGE

The key to successfully implementing the Yes = E2F3 formula is what I call the “Principle of Nudge.” We’re talking about eliciting a series of small agreements—because, after all, persuasion is seldom about evoking one colossal, ear-shattering, cosmic “YES!” People often can be most effectively persuaded when they are shepherded along gently, not yanked through the streets. A great example comes not from a shepherd, but from my sister-in-law’s goldendoodle, Lucky.

At one family gathering in their home, Lucky was being particularly affectionate. He kept rubbing against me, looking for attention, which I happily gave him. After a few minutes, I realized I was no longer in the living room, but in the kitchen. When I mentioned my surprise at the change of venue, my sister-in-law replied matter-of-factly: “He does that all the time. He brought you out here; this is where we keep his treats.”

Ah, the Principle of Nudge.

How might nudge work for you? Let’s say your persuasion priority is to convince your VP of marketing to allocate dollars and responsibility to you for a new product training initiative. Here’s an example of the series of small agreements you can elicit from your target:

- “Yes, we can meet to talk about your idea.”

- “Yes, I can provide information.”

- “Yes, I can help brainstorm options.”

- “Yes, I can talk to others in my circle to test the idea.”

- “Yes, we can run some numbers.”

- “Yes, we can pitch the board.”

Each yes slowly nudges your target to the big one: “Yes, I’ll greenlight the project.”

In most cases, you wouldn’t walk into your VP’s office and demand money and power (unless you have an absolutely monster credibility and track record, and even then I wouldn’t recommend it). That’s like asking a person to marry you on the first date. You can, but it doesn’t make for good policy.

THE FIVE-STEP PERSUASION PROCESS

Compare and contrast this:

Q: “Will you have a few minutes next week? I’d like to get your input on something.”

A: “Sure.” (See, you’ve already got your first yes!)

. . . with this:

Q: “May I have $1.5 million and complete unilateral responsibility for a project you’ve never heard of?”

A: “What is this, an episode of Punk’d? Get out of here before I call security!”

The first question suggests an informal, low-pressure exchange of information to which most colleagues would have no problem responding in the affirmative. The second question, however, defies all sense of business decorum and is an immediate turnoff (and surefire way to hear no loud and clear.) The idea behind the five-step persuasion process is to plan for and then guide your target toward the next yes. Like stepping-stones across a stream, this practice can lead you effortlessly from one agreement to the next. The art form here is your judgment. What is the appropriate next step? Well . . .

Step 1: Engage Your Target

Find the time when your target will be most approachable and receptive. (Remember, here we’re talking about one-to-one persuasion attempts; group persuasion will be covered in Chapter 8.) You’ve heard about how some people shouldn’t be bothered until after they’ve had that first cup of coffee, or how the boss is far less ornery after downing a big lunch. Well, whether it has something to do with personal preferences, biorhythms, or the phases of the moon, some people are more approachable at certain times. (One study showed that Israeli judges were more lenient on sentencing after eating lunch; tough luck for the morning defendants.)

And just as important as when is how you approach your target. Persuasion relies on relationships, so a face-to-face encounter is always better than a phone call, while an email shouldn’t even be considered when it comes to persuasion. Consider those methods three-, two-, and onedimensional approaches, respectively. Which method of engagement would you most like to encounter when you’re being persuaded?

When you’re engaging, either go with a formal meeting (“Can we meet at 8:15 in my office?”) or what some people call “systematic informality,” which is accidentally on purpose bumping into them (“Hey, I’m glad I bumped into you. I have an idea I’d love to discuss.”).

The first aspect of engagement involves building (or confirming) rapport. The most ideal situation is when you already know your target well and don’t need to do much in terms of establishing a relationship. However, if you don’t know your target all that well, begin a conversation about a common topic and then eventually transition to the persuasion topic. How do you do that? Mention a project you’re working on, offer help, ask for advice, or cite a common experience (maybe you both used to work for a competitor, but at different times). Regardless of your approach, transition to your persuasion topic.

In music, when a song changes to a different key, it’s called modulation. Often that shift is subtle (from C to C#, for example) and almost imperceptible to the average listener, but it changes the mood of the piece just slightly. That’s exactly what you’re doing when you change the energy in the room ever so slightly. You want to build on the rapport you’ve established and shift the conversation. Here are some tips and language suggestions for a smooth transition:

- Ask questions: “What do you think of [the situation you have in mind]?” “Do you have any experience in [the topic}?” You may find out that your target is already closer to your position than you anticipated.

- Cite a third party who has asked you about the topic at hand, and inquire as to whether she has been asked.

- Refer to a publication in which the persuasion topic was recently mentioned.

- Ask if your target will be attending a specific meeting or event related to the persuasion topic.

The engagement aspect is intended to begin a dialogue. I don’t advise taking a stance at this point; rather, simply explore the other person’s attitudes. Even though you may have been careful in gathering intel during the exercise in Chapter 4, it doesn’t hurt to verify your target’s viewpoints. One of the persuasion “sins” that people commit is assuming that they absolutely know where the other party stands on a certain position. Yet there are Republicans who support Democrats and Democrats who reciprocate. That’s because other factors, including geography, constituency, personal experience, and beliefs, can greatly influence perspective.

Another key engagement element is understanding your target’s level of knowledge. Has he or she been approached by others regarding the persuasion topic? Read up on it? Had personal experience in dealing with it? Or are you dealing with a blank slate? Keep in mind that independent voters and those on the so-called fence can play a significant role in the outcome of an election, despite the emotion and passion on either side of it.

This is why rapport building is so essential; it increases trust and frees up people to be honest, while also allowing them to reveal additional information. Engaging with another person and not being told the truth is worse than not engaging at all, because then you are likely to act on incorrect or incomplete information. The more time you take to build rapport with your target, the faster you can gain enough engagement to . . .

Step 2: Explore the Issue

This means delving into its content, as opposed to navigating the approach. The issue is a multifaceted situation, and each facet needs to be considered in turn. First, you need to determine what the issue means to your target, personally and professionally. By personally, I mean issues such as ego, legacy, gratification, self-worth, and off-thejob priorities. By professionally, I’m referring to promotion, remuneration, status, leadership, recognition, and perquisites.

Next, explore what the persuasion topic means to the organization. Is it transformational or minor? Can it mean recovery or market dominance? Will it be widely known and applied, or localized? What are the time implications? Are we talking about a closing window of opportunity? Is there the need to be opportunistic and innovative?

Examine budget parameters. Can this issue be accommodated within the existing budget and, if so, from one source? Or does it require several (and commensurate consensus)? Is the investment unprecedented, or has something similar already been done? Will other issues be delayed or sacrificed because of the investment?

Explore risk, too. Some people have a higher tolerance for risk than others do. Will the desired result, in your target’s eyes, justify the identified risk? Can you separate the probability of the risk from its seriousness, so your target can make separate judgments? (Great seriousness can be offset by very low probability, and high probabilities ameliorated by low seriousness.)

With these factors firmly in your mind, explore your target’s appetite for the change. Is his interest the same as it has been in the past, or is it enhanced or reduced? Can you suggest preventative actions for any foreseen risks? Have you considered contingent actions for dealing with problems that do arise?

Does your target, having explored the issue with your guidance, offer solutions, new ideas, and insights? Is she clearly excited and willing to take part or even lead? Or does she seem wary and hesitant to commit until others have done so?

All the above questions will garner important early indicators. However, the way in which you ask these questions is critical—you need to engage and explore properly. Remember that persuasion is a science; it’s a conversation. Don’t interrogate, and don’t try to wing it.

Also, don’t take sides too early by stating your opinion. Leave room for you to appear as a curious, but well-informed, onlooker. Don’t be a zealot seeking to convert; rather, ask follow-up questions for clarity and understanding. Give your target the opportunity to think and respond. And after he or she does respond, count to four and see if your target adds something else. Don’t rush to fill the silence. Amazing things can happen in between the conversation.

Step 3: Form and Frame Possible Options

Onward now to the first of our three “F” components: Forming (and framing) possible options. One of my mentors, Alan Weiss, taught me long ago that having options raises the odds of acceptance exponentially. Instead of providing a binary choice—a take-it-or-leave-it option, which is a 50/50 proposition at face value—offering three options raises your chances of acceptance to about 75 percent. In other words, you now have three shots at hearing yes.

Forming. Create varied options based on your own exploration information, but also from the responses your target provided during that process. Including some of his comments and observations will substantially increase your odds of success. Try something like this: “Not only should we look for an affiliation in Italy to launch this program, but your idea of sending our own managers over for six-month assignments is a perfect way to develop them and ensure a firsthand view by our own people.”

Additionally, most psychologists agree—and my own sales experience concurs—that three is the proper number of options. People tend to think in threes, or “triads,” because they are easy to process. Two options are simply binary (this or that), while having more than three options causes decision paralysis. For instance, research shows that television buyers bombarded with dozens of screens on display in a bigbox store tend to not buy any of them, because they fear the one they ultimately select might not truly be the right one for them. In scientific experiments, researchers have found that positive impressions peaked at three, and skepticism increased when more points were suggested.

You want to keep options within the target’s perceived range of expertise. Hence, three. Years ago, retailers created the “good, better, best” concept. And there’s a reason: It works! In fact, you should try that approach to help you form your options.

Let’s return briefly to the persuasion priority you articulated on page 11. Think about the various components of the plan and how they might be modified to create a “good,” a “better,” and a “best” option. What criteria might be modified to form these options? For instance, if you were in a pitch meeting for the Owl Towel project (introduced on pages 71–77), you might vary the initial investment, geographic scope, sales channels, and timing of the rollout—with each successive option being slightly more impressive in each of those four categories than the last. This allows your target to clearly distinguish between the “good” and the “better”—and between the “better” and the “best.” Get the idea?

Framing. When you present the options you’ve developed to your target, you need to frame them. Much like certain frames enhance or detract from the attractiveness of a work of art, how you frame your options will impact the likelihood of hearing yes or no. So prepare yourself to be the Renoir of Revenue, and the Picasso of Profit!

Always begin with the most expensive option first. If you do, your target may just select your “best” option. And if she does? Well, that’s frost on the beer mug for you and your organization. But the real reason you frame your options in this manner is because your target might say no.

Nobody likes to be turned down, because it feels like failure. But if you have a plan that you can implement in those seconds immediately after rejection, a no can be a lot less painful. This approach is often called “rejection-then-retreat,” or as Robert Cialdini sometimes refers to it, “Concessional Reciprocity.”

Walking in front of his university library one day, Cialdini was approached by a Boy Scout who asked him if he would like to purchase tickets to the Scouts’ circus to be held that Saturday at the local coliseum. The tickets were $5 each. Cialdini politely declined. Without losing an ounce of composure, the boy replied, “Oh, well, then would you like to buy a couple of our chocolate bars? They are only $1 each.” Cialdini bought two chocolate bars. Stunned, he knew something significant had just happened—because he doesn’t even like chocolate!

Analyzing this exchange, Cialdini discovered Concessional Reciprocity—the idea that when you decline someone’s offer and that person comes back with a smaller, less extreme offer, you want to say yes to reciprocate for the concession he made to you by accepting your original no.

Wanting to test this idea further, Cialdini took to the streets of Phoenix. Posing as representatives of a youth counseling program, Cialdini and his team approached college students to see if they would be interested in chaperoning a bus trip to the zoo for a group of juvenile delinquents. Seriously! Not surprisingly, 83 percent of them turned him down. (I’d be interested in studying the 17 percent who did respond positively to Cialdini’s request!) Cialdini and his research assistants then asked another group of passersby if they would consider something more outlandish. Would they dedicate two hours per week serving as counselors to juvenile delinquents for a minimum of two years? Not surprisingly 100 percent of the prospects turned down this request. When they did, the naysayers were immediately offered the smaller zoo trip request—to which 50 percent agreed, representing a tripling of the prior response rate.

As you can see, it’s imperative to have options and frame them accordingly. That way, if your target says no to one, you can retreat to your next offer. Discuss the pros and cons of each option objectively, understanding that they all lead to Rome—that is, your desired outcome. Allow the target to comment critically, perhaps eliminating one option altogether while seriously considering the other two. You might even want to combine aspects of the three options to create one acceptable hybrid. Remember, all options are fine with you, because you created them around the goal you’re pursuing. Providing choices, any one of which creates the results that you and your target require, is at the heart of forming and framing options, but this doesn’t ensure unmitigated success.

Step 4: Finesse Any White Water

Like rafting through grade five white water, the way in which you navigate resistance to your persuasion attempts will determine your success. Not every target will agree with new ideas (or even old ones). But remember that an objection is a sign of interest; apathy is your real enemy. If your target takes the time to express counterarguments, skepticism, or doubt, she is engaged enough to invest her time.

Thus, objections are a good sign. Below are the categories of typical objections and what you can do to rebut them. These are phrased in the classic “no” method, meaning your target says, “We have ‘no need’ for such a plan.” And that’s where we’ll begin:

No need. Just because you see a need, doesn’t mean others will. Needs are hardly universal, so you must create need in the eyes of your target. Use the categories we’ve noted previously (personal, professional, organizational, and so forth). Highly persuasive people possess strong capabilities of creating need among others. Find and demonstrate alternate uses that your target hasn’t yet considered. (For instance, the training program won’t just develop people in our retail channel, but can be used to develop our internal field sales force and customer service people as well.)

No money. This is probably the oldest and most common objection. “We just don’t have the money.” How many times have you heard that? Money, however, is not a resource; it’s a priority. That means there is always money. The real question is, to whom is it provided? After all, the lights are on, payroll is being met, the plants are being misted, and the parking lot is routinely getting cleaned. The point of persuasion is to ensure that existing money is provided for your persuasion priority, as opposed to something else. Consequently, making your position a high priority is essential.

Some alternatives for you are to justify the investment (see how important that ROI section in Chapter 4 is now?), explain alternate forms of payment (different departments could share in the expense, or it could be broken down over different financial quarters), or even break down the costs so they are more palatable. Few people buy a $50,000 vehicle; they buy a vehicle for $500 a month.

No time. Sometimes referred to as “no hurry” (as in, “We’re in no hurry to say yes to your idea.”). This argument—“We just don’t have the time”—is as specious as no money. There is always time. Every day contains 24 hours. The question is, what priorities will that time be relegated to? If someone says there is no time, what he means is there is no urgency, which implies that other issues have higher priorities. Hence, it’s up to you to elevate the urgency. You have to prove to your target why saying yes now benefits him. Is there a window of opportunity in the marketplace? Is there a particular resource in the organization that is available now but won’t be later? Is the mood of the organization ripe for this sort of initiative?

No trust. This is the really big one. No matter how much need, money, and time I have, I’m not going to support you or your position if I don’t trust you. Trust is a function of your target believing that you understand her position (empathy) and will help her achieve her selfinterests rather than manipulate them.

As we mentioned earlier, signs of trust include sharing humor, requesting opinions, revealing details not asked for, accepting pushback, and offering assistance. Trust can be gained in 20 minutes, after three meetings, or, sometimes, never. So here you have to keep your promises, not rush, prove your capabilities, and use third-party endorsements (and the Halo Effect!) to establish your credibility.

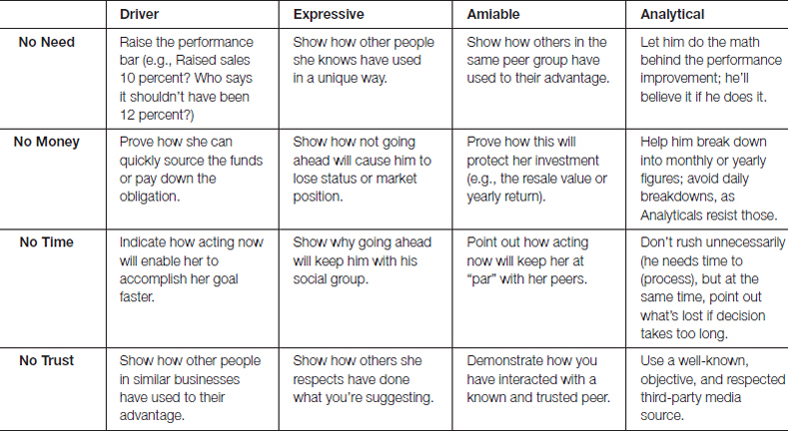

A final consideration is personality styles. (Remember the discussion about Drivers, Expressives, Amiables, and Analyticals that we introduced on pages 48–50? We’re coming back to those four categories now.) You need to tailor your argument to suit the particular objection for the personality profile of your target. See the personality/objection matrix in Figure 7-1.

The ART of Persuasion

To be successful with the five-step persuasion process you must package each step using your language skills to finesse your way through some challenging conversations. That’s when my ART of Persuasion model comes in handy. When facing one of the objections mentioned above, you’ll want to:

- Acknowledge the objection. Doing so psychologically prepares your target to hear your message.

- Respond in a substantive and compelling manner, using three key pieces of information and interesting figures of speech.

- Transition to your next nudge. Where else do you want to take the conversation?

Here’s an example: “Your new product training idea is too expensive.”

“I understand completely. At first I thought it seemed expensive, too, but then I discovered key information that changed my mind, and it might change yours. There are three reasons the program makes sense.

“First, with this program, we will improve the skills of our entire retail channel. It’s like getting three or four development programs for the price of one.

“Second, I’ve crunched some numbers, and we should have finance check them out. But if through this effort we can increase retail sales by just 1 percent globally as a result of better training, that would add an additional $15 million to product revenues. That would give this program a 10:1 return!

“Finally, we don’t want to waste all the effort required getting this product to market just to lose it with an uninformed retailer. We don’t want to quit the marathon right in front of the finish line. If we don’t take care of the market launch, the market may just launch our product.

“What do you think?”

There’s a lot going on in this example, so let me break it down. Here we demonstrated the ART of Persuasion (Acknowledge, Respond, Transition), and we used our rebuttal strategies from above (justifying costs). We also went back to the case-building chapter and referenced ROI ratios; we leveraged Cialdini’s principle of scarcity (not wanting to waste effort); and we even delved into our power language toolbox to incorporate metaphor (the marathon) and a chiasmus (“If we don’t take care of the market launch, the market may just launch our product.”)

Ending the above example with “What do you think?”—well, that takes us to the fifth and final step. . .

Step 5: Finalize and Formalize the Decision

Ask for your target’s opinion—not for a commitment. Opinions are nonthreatening: Everyone has them, and most want to share them. Simply say, “What do you think?”

If you receive a positive response (“I really like the “best” option you’ve created”), move boldly forward. Finalize and formalize the decision: “Perfect! I’ll have the purchase order on your desk by the end of the day.” And consider yours a persuasion success story.

If you receive a neutral response (“I’m still not sure”), don’t try right away to secure your yes. You have more work to do. Instead, say something along the lines of: “I understand completely. Here’s what I’m going to recommend. Don’t say yes. Don’t say no. Let’s just make sure we’re clear about what we’re talking about and willing to consider it further. Fair enough?”

What reasonable person wouldn’t say yes to that? Most will. And guess what? That’s called a “nudge.”

Ask your target why he or she isn’t sure and what would lead to greater confidence. Is information missing? Would your target like to see additional people backing your persuasion position? Does a formal plan need to be presented?

If you receive a flat-out no, employ your options: “Okay, if you don’t want to go with the training program for the entire North America distribution channel, perhaps we should just do Retailers and Field Sales Force. Or, if you prefer, just the Field Sales Force. Which of these options would you suggest?”

When formed, framed, and finessed, I like our chances of hearing yes. They’re getting better with every move. Nonetheless, there are still other considerations to keep in mind: Somewhere among a no, a neutral, and a yes response lurk mysterious X factors—such as technological glitches, competitive actions, and intrusions by a trusted adviser—that seemingly come from out of nowhere to derail your persuasion efforts. You’ll want to uncover any X factors before leaving this phase of persuasion.

Never accept a simple yes. Instead work toward a profound agreement. I call this the “Columbo method.” Actor Peter Falk played a disheveled TV detective named Lt. Columbo who became known for extracting the info he needed from sources by saying, “One more thing before I go . . .”

So take a cue from Columbo: “Is there anything we haven’t discussed that will prevent us from moving forward?” “Will you be having conversations with others who might not have the insight from our exchanges?” “In the past, has anything surfaced at the last minute to change your mind about decisions like this?”

And then you want to formalize the decision. By that, I mean you want your target to somehow go on record with his decision. Of course, for many this means a signed contract. For others it may mean issuing a purchase order. At the very least you want your target to send an email or, in conversations, tell others. This formalizes your agreement and can make it stick. Once a person goes on record, he or she will do just about anything to stick with that commitment.

WORKING FAST OR SLOW

How long will this take? These five components of this persuasion process (engage, explore, form/frame, finesse, and finalize/formalize) can be accomplished in one conversation or over a matter of days, weeks, or even months. Everything from personality to position on the issue can impact how long an effort might be required. As we mentioned previously, rarely do people change their minds in a Paul-onthe-road-to-Damascus manner. But keep in mind that once you frame your target’s options, you’ll want to close in fast.

Consider these steps a guide. After all, everyone needs a guide: Sir Edmund Hillary had Sherpa Tenzing Norgay to help him reach the summit of Mount Everest. Explorers Meriwether Lewis and William Clark had Sacagawea as an interpreter and guide as they navigated their way into the untamed lands of the western United States. Let this model be your guide as you move toward accomplishing your persuasion priority. It’s specific enough to provide key direction, yet flexible enough for your own interpretation. Leveraging a well-strategized process will accelerate your path to yes.

Chapter 7 Persuasion Points

- Remember the formula Yes = E2F3. You get to yes by engaging your target, exploring the issue, forming and framing possible options, finessing any white water, and finalizing and formalizing the decision.

- Engagement is the act of becoming approachable and determining when others are approachable.

- Exploration is the investigation of what is important to your target.

- Forming and framing options enable the “choice of yeses,” which vastly increases your persuasion ability.

- Finessing the white water includes overcoming the four objections most commonly encountered: need, money, time, and, most important, trust.

- Time and money are priorities, not resources.

- Depending on the circumstances, the persuasion process can be accelerated. But it also may need to obey a caution flag every now and then.

- Consider this chapter your navigation guide to leveraging your speed and ensuring your direction.