CHAPTER 11

Your Persuasion Action Plan

How to Get a 10,000:1 Return on Your Investment in This Book

I know what you’re thinking: A 10,000:1 ROI is an outrageous claim! (After all, you read Chapter 4, so you’ve mastered ROI calculations.) Okay, since you brought it up, let’s do the math.

If you paid $25 for this book, then $250,000 would get you in the ballpark of a 10,000:1 financial return. For a typical consultant, that would be comparable to securing five $50,000 contracts. A salesperson earning 15 percent commission would need to sell approximately $1.65 million worth of goods or services. A salaried person working for a corporation could realize that kind of return by jumping from a $100,000-a-year job to a $150,000-a-year job in a few short years.

All of these scenarios are well within the realm of possibility. But you need to apply the ideas—or all bets are off. You also need to be willing to take some chances, so consider this: What are you willing to do to make it?

In the August 31, 1972, East Coast edition of Rolling Stone magazine, an unknown musician named Peter Criscuola ran an ad that read: “Drummer: willing to do anything to make it.” Two guys looking to create a band, Stanley Eisen and Gene Klein, called Peter to explore his seriousness. “Would you wear a dress onstage?” he asked. “Would you wear high heels?” “Would you wear . . . makeup?”

And the rest, as they say, is KISStory.

Peter Criscuola became Peter Criss; Stanley Eisen became Paul Stanley; and Gene Klein became Gene Simmons. The trio quickly added guitarist Ace Frehley, and the rock band KISS eventually wound up in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. Perhaps the story of the band’s origins is apocryphal—but if it didn’t happen, it should have.

I’m not suggesting you dress like your favorite member of KISS on casual Friday, but those guys were willing to go beyond the norm and define new parameters for rock music and performance in the face of early ridicule. So what is your answer? What are you willing to do to make it?

POWERING THROUGH UNCERTAINTY

You may remember that we discussed cognitive biases in Chapter 2. As you well know, they are always in play—affecting our thoughts and actions, as well as those of our targets. And when it comes to taking action, one bias is particularly insidious—the certainty illusion, which is sometimes described as “the unreasonable desire for 100 percent confidence or certainty.” Yet few aspects of life are certain. We can’t be certain that a doctor’s prognosis is correct, that voting machines are infallible, that the Green Bay Packers will win the Super Bowl. This, however, shouldn’t stop us from getting the physical exam, doing our civic duty, or watching the Packers-Bears game on Monday night.

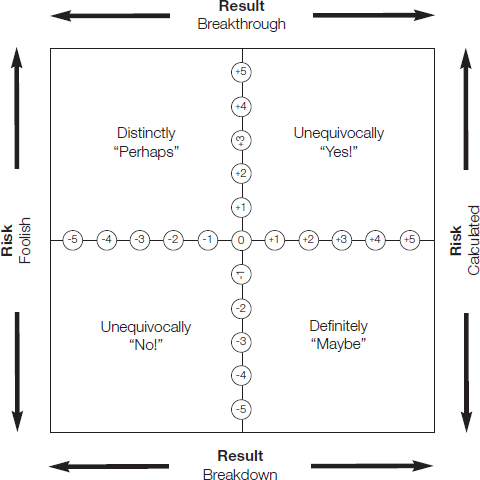

On page 11, I asked you to define your persuasion priority. Now, we’re going to do more than just consider the issues; we’re going to jump in the pool and start making some waves—which means taking deliberate, purposeful action. So let’s examine your persuasion priority from two perspectives: risk and result.

Taking No Risk

Peek ahead to Figure 11-1 on page 195. This is going to be the object of our discussion for the foreseeable future. This figure has a number of distinguishing features, and we’ll discuss each in turn. For the time being let’s focus on the risk continuum scale—the x axis that spans from Foolish Risk on the left to Calculated Risk on the right.

The risk continuum scale should look somewhat familiar to you from the figures in the first few chapters, but this one is articulated by numbers, because in this situation it’s important to think of your actions and results in terms of degrees, not just black-and-white conditions. Not pursuing a priority connotes no risk. Consequently, it is represented by the 0 in the center of the risk continuum scale. Every step away from the center moves increasingly toward either a negative or a positive risk.

Moving Toward a Foolish Risk

The degree of foolish risk depends on how far to the left you move on the continuum.

– 1: Making an out-of-the-blue ask of a friendly target: “Jim, how about if you let me craft the proposal?”

– 2: Making a significant out-of-the-blue ask of a friendly target: “Jim, would you like me to make the client presentation?”

– 3: Making a significant request, with little case building, of a negative target: “Steve, I know we haven’t always seen eye-to-eye, but I have a gut feeling that this is the way to go.”

– 4: Making a significant request, with little case building, of a negative target group: “Look, Steve, I know this executive group has turned us down before, but I really think we have a winner with this product.”

– 5: Making an insistent, emotional plea to senior management with no proof or evidence: “I know you’re the CEO, but you have to listen to me. This is what’s going to happen. I can feel it.”

Moving Toward a Calculated Risk

The degree of calculated risk depends on how far to the right you move on the continuum.

+ 1: Planting the seed for a reasonable new request of a friendly target: “Jim, I’d love to broaden my skill set. Maybe sometime you could teach me how to put together a winning proposal.”

+ 2: Making a reasonable new request of a friendly target: “Jim, would you like me to have a go at writing the proposal, and you can critique it?”

+ 3: Making a significant request, with solid case building, of a negative target: “Steve, I know we haven’t always seen eye-to-eye, but I’d like to start fresh. Your team and I have put together some numbers on the new project, and it might have some merit. Would you be willing to let us know what you think?”

+ 4: Making a significant request, with solid case building, of a negative target group: “Look, Steve, we’ve done our homework for this project and anticipated every possible objection and rebuttal that could come our way. It’s gonna work.”

+ 5: Making a well-constructed, well-substantiated case to senior management: “We’ve analyzed this quantitatively, we’ve attempted to evaluate this qualitatively, and we’ve tested this position from three different viewpoints. We think it’s a solid proposal.”

Yielding No Result

Now let’s take another peek at Figure 11-1 and talk about results. If there is no payoff for you, that would be represented by a 0 on the y axis—meaning you are status quo. Have you ever expended a tremendous effort on a project and gotten nowhere with it? That’s what we’re talking about here.

At the extremes along the y axis, we have “Breakthrough” and “Breakdown.” Moving toward a breakthrough indicates you’re on an upward (positive) trajectory, while a “breakdown” suggests you’re starting to lose credibility or your persuasion panache. Let’s look at the degrees in between.

Heading for a Breakdown

The degree of breakdown depends on how close to the bottom you move on the scale.

– 1: Mild embarrassment in front of a coworker and some time wasted: “Mike, I read your proposal. There are several miscalculations in it.”

– 2: Mild embarrassment in front of a group of colleagues and significant time wasted: “Hey, Mike. The team looked through your slide deck. We can’t let you go to the client with this presentation.”

– 3: A setback in front of your boss: “Sally, we know you’ve been working with Mike, but this report just won’t cut it.”

– 4: A setback in front of your boss’s boss: “Who hired this guy?”

– 5: Failure, resulting in significant financial loss, legal action, and reputation damage: “Mike, we lost the business, the client has filed suit, you’re named as a defendant, and they’re profiling our failure on 60 Minutes.”

Heading Toward a Breakthrough

The degree of breakthrough depends on how close to the top you move on the scale.

+ 1: You’ll feel good about your accomplishment: “Hey, I did pretty well running the numbers on the project.”

+ 2: Others in your group will notice your accomplishment: “That was a very compelling presentation!”

+ 3: Your boss will formally acknowledge your win: “Stephanie, I want to thank you. You did a great job bringing aboard that client.”

+ 4: You’ll experience an increase in compensation and repute: “Stephanie, as a result of your success, I’m issuing you a new title and a new salary grade.”

+ 5. This will be a game changer for you and your organization: “Stephanie, that project will make us number one in market share, thanks to you. That’s why I’m appointing you senior VP and naming the west corner meeting room after you.”

As stated earlier, you might choose different descriptors for your estimation of risks and results, but it is important to consider both. Now, when we cross-reference both of these conditions, the full picture of your persuasion possibilities comes together.

Navigating the Four Quadrants with Intention

Figure 11-1 depicts what I call “decision quadrants.” This model can help you think through your efforts in advance and help you decide whether you want to move forward with your actions. Generally speaking, the farther your score is from center, the more intense the sentiment. Think of this as the volume buttons on your iPhone.

If you find yourself in the lower-left quadrant, what I call the area of “Unequivocally ‘No!’” for example, the pain of “no” will be tough to recover from. I call the lower-right quadrant “Definitely ‘Maybe.’” It’s a calculated risk, and you’ve got a shot, but the payoff isn’t overwhelming. So why is it “Definitely ‘Maybe’”? Because it might give you exposure to a new person, or it might give you a “live fire” opportunity to practice a new skill, such as making a presentation or running the numbers. So, although there may not be a meaningful enough return, you still might receive some benefit. Remember the breakdown scale states −1 through −4 as mild embarrassment to a setback. Sometimes you have to break down before you break through.

The upper-left quadrant, “Distinctly ‘Perhaps,’” combines the more dangerous side of the risk scale with the more appealing side of the result scale. That’s why actions here require careful consideration. Let’s say you receive a phone call notifying you of an impromptu meeting with senior managers to discuss specific aspects of a new product launch. The meeting is in one hour, and you have a great idea for the marketing campaign that you’ve been thinking about pitching. Perhaps it’s not yet crystallized, or you haven’t organized your case as well as you’d like, or thought through every aspect of your request, and now there’s no time to generate hard numbers. But at this meeting, you may have a shot at making your request. Should you take it? Welcome to the game!

The upper-right is the easiest quadrant to discover you’re in. The payoff is on the positive end of the result continuum, approaching “Breakthrough,” and despite the risk, you like your chances. This is the quadrant of “Unequivocally ‘Yes!’” And the bigger the payoff and the more calculated the risk, the higher your intensity should be to pursue this priority.

If you’re convinced you’re engaged in a worthy cause with reasonable risk and positive reward, its time to create your Persuasion Action Plan.

YOUR SEVEN-STEP PERSUASION ACTION PLAN

By now, you should be familiar with the basic elements of your Persuasion Action Plan—you just don’t realize it yet. However, in Chapter 1 you learned how to clearly state who is the one person you want to do what as well as how to determine why this is important for you, your target, and your organization. In Chapter 3 (and a bit in Chapter 4) you learned how to assess your primary target and other key influencers. In Chapter 4 you learned how to build your quantitative and qualitative case. In Chapter 6 you learned how to plan your language (by deliberately using adjectives, metaphors, examples, stories, humor, and so forth). In Chapter 7 you learned how to create your action steps. And in Chapter 8 you learned how to map the persuasion territory. Now it’s time to put all those skills together and create your own, personalized step-by-step Persuasion Action Plan that fast-tracks you on the road to yes!

Step 1: Set Your Persuasion Priority

Clearly state who is the one person you want to do what. Keep in mind the four persuasion priority criteria: Your ask must be meaningful, significant, realistic, and others-oriented. And it must be specific. (Reminder: Don’t say: “I want my senior vice president to add some people to my staff sometime.” Instead say: “I would like my senior vice president to approve five key new hires for my department by the start of next quarter.”)

Now it’s your turn: Who do you want to do what?

I want _______________________ to _______________________

_______________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________.

Step 2: Articulate Why This Priority Is Important to You, Your Target, and Your Organization

Strive to identify at least three reasons for each of the three categories. These can include finances gained, skills acquired, networks built, market shares increased, reputations improved, and others.

Important to you: ______________________________________________

Important to your target: ________________________________________

Important to your company: _____________________________________

Step 3: Build Your Quantitative and Qualitative Cases

When building your quantitative case, you’ll want to articulate the anticipated Return on Investment (expressed in dollars, as a percentage, or as a ratio). If you’re strategizing a larger and longer-term project, what might be the Net Present Value and the Internal Rate of Return? What other benefits of achieving this priority can be readily quantified?

When building your qualitative case, you want to ask questions such as: Will your initiative result in sustained high morale (and how might you know)? Will the initiative lead to more effective teamwork? (If so, what might be the evidence?) What other qualitative reasons (and subsequent evidence) can you add?

Step 4: Plan Your Language

What savvy phrases can you use to describe your request or facets of your request? (You might describe “a compelling argument, a sensitive situation, a crucial decision,” for instance.) Questions work, too: “Do we want to surrender to the competition?”

What figures of speech (metaphor, simile, analogy) can you create to describe your request or subsequent risks or rewards? “This guy is the Peyton Manning of sales directors.” “That part of the country is a marketing black hole.” “The likelihood of the board approving that approach is less than that of Lady Gaga wearing a turtleneck tomorrow.”

Using the power of storytelling, develop a brief and relatable story to justify your request, address potential challenges, or describe imminent rewards. Be sure your story has a purpose, includes a captivating open, establishes a plot, inserts an unexpected element or a couple of humorous comments, and concludes with a learning point.

Anticipate resistance and objection. How will you respond when someone says, “It costs too much”? Or, “We don’t need it”? Or, “Now is not the right time”?

Step 5: Assess Your Primary Target and Other Key Players

You certainly don’t need to list every person who might be involved in your request, but it’s critical to evaluate your primary target and the key players. Write down their names and titles, your impression of their personalities, and your perception of their preferences for communication and information. For example: “Steve Miller, VP Field Operations; Expressive; text messages; just the facts.” Or: “Sandra Mathers, General Counsel, Analytical; face-to-face; all the details.”

Step 6: Map the Political Territory

If your persuasion priority involves more than a few people, represents significant dollars, and is likely to take some time, you should map the political territory. Using the information covered about this technique in Chapter 8, answer five basic questions:

- Who are the key players?

- On a scale of −10 to +10, what is each player’s influence in the organization?

- On a scale of −10 to +10, to what extent is each player applying that influence in this situation?

- What are the chances (low, medium, or high) that each player might change his or her position?

- What significant relationships exist among key players?

Use the information culled from the previous five questions to create a data sheet, and then map your political territory like we did in Chapter 8.

Step 7: Launch the Five-Step Persuasion Process

By this point, you have thoroughly evaluated your risk and reward, as well as determined whether you’d like to move forward with your persuasion priority. You’ve articulated your request, and identified not only your self-interest, but also the enlightened self-interest of others. You’ve crafted your case, crunched the numbers, created compelling language, and counted on and counteracted any resistance. You’ve identified the key players in your request, considered their personalities and preferences, and mapped your persuasion terrain. Now you’re ready to launch the five-step persuasion process (introduced in Chapter 7) that will take you to your objective. Remember the magic formula: E2F3? To recap:

Step 1: Engage your target on the topic; ask for his or her input.

Step 2: Explore the issues—with your target and others. Brainstorm options, run numbers and different scenarios, and so forth.

Step 3: Form and frame options to get your desired result.

Step 4: Finesse any white water and ask for your target’s opinion.

Step 5: Finalize and formalize the decision—and create perpetual yes.

While engaged in this process, make sure you avail yourself of all the ideas we’ve talked about on the previous pages. Of course, you won’t use all the tools and techniques all at once. Just as a surgeon carefully selects his blade or a golfer her club, your skill and ability to choose and use these techniques will determine your success.

The classic model for the persuasive process has five steps, as defined above. However, each situation is unique, and this model is meant to be flexible. So create as many action steps as is helpful and necessary for the foreseeable future. (For instance, you might want to meet with the financial analyst to see if the numbers make sense before proceeding to the official “Step 1.”) However, don’t make your sequence overly complicated. You probably don’t need 27 action steps, but 2 might be too few. You can then adjust accordingly as your persuasion campaign develops.

Why do you think NFL coaches script as many as the first 15 plays they plan to run? To test the waters and gauge how opponents react, of course, as well as to determine if there are weaknesses, such as a poor pass defense, that can be exploited. Just like coaching, persuading is an art form, and it takes time to master.

To ensure that you fully think through each of your action steps, try implementing the “what, when, why, and how approach.” For instance, if you do decide that you need to review the numbers with the financial analyst before proceeding to the official “Step 1,” you might articulate your goals for this as follows:

What: Approach financial analyst Corey Williamson and ask for ROI estimate input.

When: Before COB next Friday.

Why: We have a great relationship, so he’ll be honest with me when evaluating both pros and cons. Presenting a solid financial case will show I’m serious. Plus, if this idea doesn’t prove to have a great ROI for the company, I shouldn’t move forward.

How: Corey is at his best in the morning. He’s also a text message guy who hates surprises and loves details. I’ll send a text, set up an A.M. meeting, and bring all the details for his perusal.

Try scripting the five steps in your persuasion process in this manner and see what develops.

THE PAYOFF OF PLANNING

When I present persuasion this way, more than one person usually asks me, “Do I really need to do all this? Can’t I just go pitch it?” Sure, you can. It all depends on how big your ask is and how important the result is to you and your organization. You certainly wouldn’t unleash your Seven-Step Persuasion Action Plan horsepower when trying to persuade someone to go to a seafood restaurant for lunch. But if you’re vying for that coveted assignment, looking to add significant numbers to your staff, or pitching your board of directors on a new strategic initiative, you better be on top of your game.

The rule of thumb is that planning pays off in a 5:1 ratio. Every hour you spend planning pays off by saving you roughly five hours of misdirected effort. So do the planning work up front and save the execution headache later.

As you can tell from my tone throughout this book, it’s important to have a sense of humor about persuasion. Yet, at the same time, these are seriously powerful approaches for people who are serious about success. If you fit this description, I have just one question before this chapter’s Persuasion Points:

What are you willing to do to make it?

Chapter 11 Persuasion Points

- Relentlessly seek opportunities to take calculated risk for breakthrough results.

- Always consider the environment of your organization or setting when determining your Persuasion Action Plan.

- Evaluating the risks and potential results of your persuasion priority allows you to take deliberate and purposeful action.

- Scripting your five-step persuasion process will help you better develop and perfect your pitch.

- Just like coaching football, persuading is an art form, and it takes time to master.

- A sense of humor can pay off during the persuasion process.