CHAPTER 1

Persuasion Fundamentals

The Basics You Need to Know, and Why You Need to Know Them

“Will you do it?”

The surrounding offices were still and dark. Even the up-and-comers had gone home for the evening. An ancient vacuum’s tortured whine pierced the quiet as the nighttime custodial crew worked its way down the hall. The hum of the cheap fluorescent lights overhead added an interrogation-room quality to the discussion.

Sally Matheson, the marketing vice president in charge of the project, waited patiently, her calmness masking the fact that a multimilliondollar project’s deadline hung on the answer to the question she’d asked just minutes ago. IT Vice President Peter Simmons—the best in the organization, maybe the business—had heard Sally ask for help countless times during the past five years; he knew her well.

Sally faced one of the toughest persuasion challenges: peer to peer. She had no ability to reward or punish. No desire to threaten or cajole. Everything boiled down to this relationship and her ability to persuade.

* * *

Has your success ever hinged on someone agreeing with your initiative? Have you ever watched a project fail due to lack of buy-in? Stood dumbfounded as someone else was handed the promotion you coveted? Watched a potential client pass on your proposal in favor of a more charismatic competitor?

Whether you are in the executive suite, in middle management, or on the front lines, persuasion skills are crucial to ensuring that you have the best chance of career success. If you internalize the concepts in this book, you will be able to ethically convince more people to get on board with your ideas, more quickly and more effectively than you ever imagined. You’ll be able to generate organizational “buzz” for your initiatives, your results, and you, creating professional evangelists who will sing your praises.

In meeting rooms, hall chats, and off-site gatherings, the word will be: “You can’t move on that project until you talk to her.” Or “Don’t even try to launch that product without consulting him.” Not because you hold some hierarchical power or budget (although that may be the case), but rather because you have such professional gravitas.

In order to reach that point in your workplace environment, though, you need to start somewhere. Let’s begin with key definitions.

WHAT IS PERSUASION?

To the uninitiated, the term persuasion has negative connotations. “You’re not going to persuade me!” they say defiantly. Or the well-intentioned person may proclaim, “I would never try to persuade someone.”

Persuasion is not coercive, conniving, or devious. Drop that inaccurate psychological baggage right now. No one can be persuaded to do something he or she doesn’t want to do. The person may have second thoughts or buyer’s remorse, but that’s another subject entirely.

I define persuasion as “ethically winning the heart and mind of your target.” Let’s take a moment to examine this definition word by word. Ethically means simply doing something honestly and without trickery or deceit. Winning means gaining agreement with your suggestion, idea, or position. Heart refers to gaining emotional buy-in, mind refers to logical buy-in, and target represents the specific person you are attempting to persuade. (To make the ideas presented here more accessible, the first seven chapters will look at persuasion through a one-on-one lens; Chapter 8 will cover how to apply persuasion in group settings.)

A term often used in conjunction with persuasion is influence. Influence is the capacity to become a compelling force that produces effects on the opinions, actions, and behavior of others. Occasionally, I’ll use the term influence as an effect that “nudges” a target toward thinking positively about my request. But I’d like for you to primarily think of influence as your professional and personal credibility, your organizational and political capital, your corporate “sway.” Persuasion is an action; influence is a state or condition.

I’ll say this again: One thing persuasion is not? Manipulation. Nor is it underhanded or self-serving. Could you use the tactics in this book in a manipulative and self-serving manner? Sure. Will you reach agreement? Absolutely!

Once.

After that, your persuasive powers with that particular person will be all but finished. Manipulation does not help build long and lucrative careers. Whether you’re attempting to persuade or dissuade, you have to be doing it for the right reasons and in the right manner. Here and there, I’ll point out how some people use persuasive tactics in ways that are clearly manipulative (such as the real “Wolf of Wall Street”), while some companies and brands skate the fine line between ethical and manipulative persuasion. However, my underlying assumption, as author, is that you, as reader, will always be operating with the best interests of your target, your clients, and your organization in mind.

TWO PRIMARY ROLES OF PERSUASION

To understand what persuasion can do for you and your career, we must begin by clarifying the two fundamental roles of persuasion. The first involves getting someone to say yes to your offer or request—to buy your product, agree to your idea, or take you up on your suggestion. Persuasion helps you get someone to willingly do something. You may want that person to:

- Approve a higher head count: “Will you sign off on my four new field sales positions?”

- Enter into a business relationship: “Do we have a deal?”

- Support your initiative: “Will you back my proposal at the board meeting?”

The second role of persuasion—and one that many people overlook—is getting someone not to do something, to dissuade him or her from taking action you feel might be harmful, such as using a particular supplier or launching a particular product. For example, you may want that person to:

- Not go ahead with a new business partnership: “That firm is just bouncing back from bankruptcy; do you think we should partner with it?”

- Discontinue, or at least rethink, an existing initiative: “Our East Coast teams aren’t seeing much client interest.”

- Change a decision, or at least continue due diligence: “Do you think he is the right person for the job? If we keep looking, we might be able to find a better fit.”

Law enforcement officers in San Francisco use the power of dissuasion very effectively. Bicycle thefts are so widespread that a special task force uses GPS-tagged bait bikes to catch would-be thieves, which forces small-time criminals to ask themselves one significant question before they steal: Is this a bait bike?

If you’re going to thrive in the eat-or-be-eaten contemporary workplace, you must be able to effectively use both roles. This book provides you with a competitive advantage, because your competitors are more than likely not focusing on their own persuasion skills. Why? Consider a condition I call the “Persuasion Paradox.”

THE PERSUASION PARADOX

In a nutshell the Persuasion Paradox can be summarized thus: Although persuasion is crucial to people’s success for many reasons, they actually spend very little time and effort improving their persuasion skills. In fact, at best, many professionals take a mindless approach to persuasion. At worst, they abhor the practice of persuasion, striving to avoid it. The mindless ones, either consciously or subconsciously, assume that just because they’ve heard people say yes to them—and they’ve given the same response to others—they understand the complexities of attaining agreement. This supposition couldn’t be further from the truth. The act of persuasion remains a significant obstacle for many professionals, and they might not even be aware of it. However, like failing to check your blind spot before darting out into the oncoming lane on a narrow highway to pass a slow-moving vehicle, ignoring this obstacle can lead to disastrous results.

The ones who abhor persuasion treat it like a dead rodent. They want nothing to do with it, think it smacks of the dreaded word sales and conjures images of white shoes, plaid jackets, and glad-handing used-car salesmen. But successful people, who are neither mindless nor abhorrent, don’t see persuasion that way. Professionals at the top of their game understand not only that it is okay for them to promote their ideas and issues, but that it is incumbent on them to do so.

Having someone say yes to your ideas, offers, and suggestions ranks among the greatest achievements in the business world. It represents validation, respect, and acceptance among your peers and others. In author Daniel Pink’s survey of American workers, “What Do You Do at Work?” for his book, To Sell Is Human: The Surprising Truth About Moving Others (New York: Riverhead Books, 2012), he discovered full-time, non-sales workers spent 24 out of every 60 minutes involved in persuasion efforts. To say effective persuasion is merely important is to make an extreme understatement.

Persuasion requires intellectual heavy lifting. Understanding your target, knowing how to increase the value of your offering (or, conversely, decrease the resistance of your target), choosing the right words, and determining the timing of your persuasive efforts all are prerequisites of effective persuasion. The fact that you are reading this book means you’re willing to take steps to break out of the Persuasion Paradox. No approach or technique can guarantee persuasion success, but if you put into practice the ideas and advice found on these pages, you will dramatically increase your chances.

So, let’s talk about you and yes.

SETTING YOUR PERSUASION PRIORITY

Let’s consider your career. If, in your professional endeavors, you could flick a switch and convince one person to do just one thing, what would that be? Do you want to get the assignment? Bring a new product to market? Overhaul the Customer Service Department? Win the promotion? Land a big-name client? Secure a budget increase?

Each of these is what I call a “persuasion priority.” To get to the heart of the matter, ask yourself this: Who is the one person you want to say yes, and to what? Note: When setting persuasion priorities, it’s often more effective to state them in the affirmative, even if you’re attempting to dissuade someone. For example, if you want your target to not choose a particular vendor, phrase your priority along these lines: “I would like Steve to weigh other options before choosing his vendor.” Before you answer the above persuasion priority question, consider the four persuasion priority criteria. Your persuasion priority must be:

- Meaningful: Important to you and your organization

- Significant: Large enough to make a difference in your life and workplace

- Realistic: But not so large a request that it’s unattainable

- Others-Oriented: Because you get ahead by improving the condition of others

Be specific, too. Avoid generalizing with a statement such as, “I’d like my boss to give me more responsibility.” That’s too imprecise. To increase your chances of persuasion success, specificity is crucial: “I want my boss to give me responsibility for the Latin American project.” Don’t say: “I want my senior vice president to add some people to my staff.” Instead, say: “I want my senior vice president to approve five key new hires for my department next quarter.”

Stop reading right now and write down your persuasion priority, which you will keep in mind as you work your way through this book:

I want _______________________ to _______________________

_______________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________.

Of course, at any given time, you’ll have multiple issues and objectives for which you seek agreement. But if you’d like to receive the biggest return on your investment of time and money in this book, keep your persuasion priority top of mind. As you move through these pages, strategies and approaches will emerge to significantly increase your chances of getting to yes. And if you’ve chosen your objective carefully, achieving it will have a dramatic and overwhelmingly positive impact on your career—and perhaps your life.

SELF-TEST: ARE YOU MADE TO PERSUADE?

Behavior is how you conduct yourself in a given situation. In professional settings, wildly persuasive people balance the following attributes:

- Assertive: Inclined to be bold and self-assured

- Empathetic: Possess the ability to see the world from another person’s perspective

- Communicative: Adept at applying verbal and nonverbal communication

- Tenacious: Extremely persistent when adhering to or accomplishing something

- Resilient: Possess the ability to recover quickly after hearing no

Evaluating Your Skill Sets

Now it is time for you to evaluate your natural persuasive abilities. Rank yourself in each of the five areas based on the descriptions above. A word to the wise: Doing “well” on this self-test isn’t about scoring 10 in each area; it’s about possessing the right blend of these key behaviors. After all, a strength overdone is a weakness. (Let’s say you have great voice inflection and people find you an engaging and persuasive public speaker. Go too far with that voice inflection, though, and you’ll sound like a crazy—and not-at-all-convincing—late-night infomercial host.) So be honest in your self-critique. And try to resist the temptation to peek at the scoring while you’re doing this. This self-test will be most useful to you if you have honest results.

Assertive

Low: You rarely ever raise a new or contentious issue with others.

Medium: You regularly speak out in meetings and present cases for your statements.

High: Others might describe you as hardheaded or strongly opinionated.

Low Medium High

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10

Empathetic

Low: You rarely consider another person’s perspective.

Medium: You easily determine when others want or don’t want to continue a conversation.

High: You’ve cried tears of joy at another’s success.

Low Medium High

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10

Communicative

Low: You tell everyone the same thing, the same way; you also send a lot of group emails.

Medium: You can explain most things to most people.

High: You intentionally vary both verbal and nonverbal approaches to suit your audience.

Low Medium High

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10

Tenacious

Low: You try to convince people of an idea, but you’re not going to force them to agree with you.

Medium: When you want something, you’ll keep trying to get it for a good long time.

High: You hold on to your positions and objectives forever.

Low Medium High

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10

Resilient

Low: When people say no to you, you feel personally rejected and depressed for days or weeks.

Medium: When rejected, you feel down, reflect on what happened, then move on.

High: Nobody likes to hear no, but you quickly shrug it off and move forward.

Low Medium High

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10

Interpreting Your Results

Here’s my take on the optimum score for each essential behavior:

Assertive: Ideally, you should score around a 7 here. You certainly can’t be devoid of assertiveness and be considered persuasive; at the same time, if you gave yourself a 10, you might have already crossed the line from assertive to aggressive.

Empathetic: An 8 is great. You can’t be tone-deaf to the other person’s needs, but you also shouldn’t make your objectives completely subservient to your target’s every whim. You want to put yourself in the other person’s shoes temporarily—not live there.

Communicative: This is where you want to hit the persuasive ball out of the park. Communication skills are crucial. What you say, how you say it, where you say it, when you say it, and what you’re wearing all count. You want to be at your best, using both verbal and nonverbal communication to suit the message needs of your audience in much the same way a chameleon changes colors depending on mood and circumstances.

Tenacious: This one might surprise you. To be a persuasive professional, you should score only about a 5 or 6 on the tenacity scale. If you hold on to your ideas too tightly, you may quickly establish the reputation of someone who is unreasonable or obstinate. The key to knowing when you’ve gone too far is having the ability to decode corporate-speak. When people start telling you they “like your passion,” that’s code for “We think you’ve lost your mind.” When you hear that, ease off the throttle.

Resilient: You need to score around a 9 here, because you will face a lot of rejection in your career. No one hears yes all the time, so you better learn how to handle no appropriately. If someone doesn’t like your suggestion for the new marketing campaign, and you sulk about it for weeks, considering it as some sort of personal condemnation, you’re setting yourself up for a brutal existence. I’m not suggesting that you be completely unfazed by rejection, however; momentary unhappiness can stimulate you to reflect and make important and necessary adjustments. But the key here is taking action after hearing no. Do you get back to work quickly? People who score a 9 in resiliency do.

It’s important to understand that your ability to improve is not based on some sort of inherent genetic disposition. You don’t need to be born with a silver tongue in order to be successful at persuasion. If you naturally have what it takes to be a persuasive individual, congratulations! The following chapters will amplify those strengths. But if you aren’t a natural, find reassurance in the fact that persuasion skills can be acquired, and know that the information here will dramatically improve your persuasive abilities.

PERSUASION PRECEPTS

Now that we’ve defined persuasion and its purposes, explored your immediate persuasion priority, and examined behaviors necessary for persuasion success, let’s turn our attention to three key foundational ideas on which your persuasive efforts will be built. These ideas are reciprocity (the linchpin of persuasion), a fascinating concept referred to as “enlightened self-interest,” and the ultimate persuasion principle: congruency.

Reciprocity

Reciprocity is a fundamental human condition that means a “cooperative interchange,” or the repaying of others in kind, often for a mutually beneficial result. This give-and-take understanding between humans is essential to our existence—it’s basically the reason our species has endured on this planet. Reciprocity is about surviving—and thriving—within your own organization. Likewise, understanding reciprocity is vital to maximizing your yes success.

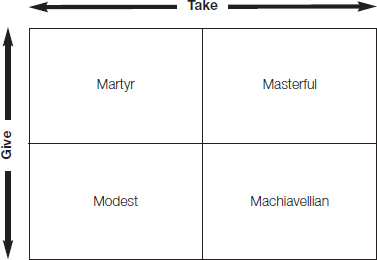

And the first step to doing so involves establishing a healthy giveand-take mindset. The matrix in Figure 1-1 will help you think about how you currently leverage (or don’t leverage) reciprocity. There are two planes to consider: your willingness to actively do things for others, and your willingness to accept assistance from others.

Do you “give” a lot? Do you provide favors, information, and insight to others? Or do you keep to yourself? Do you willingly accept favors, information, and insight? Or do you insist on going it alone, like a solo climb up Mount Everest? Let’s evaluate each mindset.

Martyr. If you give a lot but accept very little in return, you’re creating a martyr-like professional condition. In his purest form, a martyr either suffers greatly or is willing to die for his cause. Sometimes, professionals give without receiving, but they don’t for long, because it’s simply not a sustainable position. One reason people find themselves playing the role of martyr is because they refuse to accept reciprocated behavior. How many times have you heard yourself saying this to a colleague trying to return a favor: “No, that’s all right—no need to repay me.” Granted, you might say that in an effort to be magnanimous. But don’t. In a situation where the other person’s perceived obligation to repay you is strong, she may actually like you less if you don’t allow her to reciprocate. Drop the martyr act.

Modest. By failing to help others—and likewise failing to accept others’ help—you’re allowing no one to benefit from your presence. That greatly diminishes your contribution to others and your organization. This type of behavior may very well have provoked Oliver Wendell Holmes to write: “Alas for those that never sing, But die with all their music in them!” If you don’t give or take, you’ll always be stuck in neutral.

Machiavellian. Niccolò Machiavelli’s portrait in world history has been painted with a black brush, largely because of the Italian politician’s views on winning, losing, and manipulation. You might be similarly casting a shadow on your reputation if you operate in a manner that others perceive as selfish. You succeed when you create allies, not adversaries.

Does someone in your organization constantly ask for favors but not even attempt to repay them? Does that person always seem to take credit for the work of others? Does he or she promise the world but never deliver even a small corner of it? You bet. Pause now and take note of the negative feelings you’re experiencing by merely thinking about people like that and their actions. That’s because they offend your sense of justice. Make sure you’re not acting in a Machiavellian manner; otherwise, people will be thinking of you with that same outrage.

Masterful. When you give generously and accept repayment in kind, you both contribute greatly and benefit greatly. Best of all, people will think highly of you. The “Masterful” quadrant is where you want to spend most of your time. One of the main reasons people don’t find themselves in this quadrant nearly enough is that they fear their contributions will not be reciprocated. Don’t get caught thinking that way. Not to go all “California woo-woo” on you, but if you do good things, good things will happen to you. (Later, I’ll show you how to nudge karma in your direction.)

Helping someone by reviewing his presentation, or obtaining a piece of information a coworker needs, or serving as a sounding board while a colleague from another department vents all rank as valuable behaviors you can provide for others. When you do these—or implement any similar positive reciprocity behavior—your actions likely will be reciprocated. This is the necessary give-and-take nature of the persuasively masterful.

Do not misinterpret the give-and-take mindset as tit for tat. This is a general guiding notion, not an accounting ledger. You want to help others and accept their reciprocal actions, not track how many minutes you’ve given and then expect the same in return. (Do that and people will call you other names!)

How Senses Affect Persuasion Efforts

The type of beverage you drink, the surface of the chair on which you sit, and the color of clothing you wear all play a role in getting to yes (or no) faster. Thalma Lobel, a Ph.D. and director of the Child Development Center at Tel Aviv University, maintains that decisions, judgments, and values are derived as much from outside factors as they are from our brains. In her 2014 book, Sensation: The New Science of Physical Intelligence (New York: Atria Books), Lobel provides scientific evidence of how targets respond to common situations that, on the surface, appear insignificant:

- People drinking warm beverages such as coffee or tea are judged by their targets to be more generous, caring, and goodnatured than those enjoying such cold beverages as soda or iced coffee. The concept of “warm” and “cold” extends beyond the drink and transfers to the individual drinking it.

- That “warm/cold” mentality is at play in other facets of our lives, too. Take the chair you opt to sit in while making your pitch. Studies suggest harder chairs make people tougher negotiators, while softer chairs reduce their aggressiveness. Hmmm. Maybe you should add a soft and comfy chair to your office for guests . . .

- Researchers found that men consider women who wear a red blouse (as opposed to a blue, green, or gray blouse) consistently more attractive. Red represents strength, power, and energy. Wear it when you need to hear yes.

Enlightened Self-Interest (and Other Persuasive Methods)

Although technology, society, demographics, and economies have changed greatly as the world has evolved, some persuasive patterns remain remarkably unaltered. The oldest method of getting someone to do something is through a reward-or-punish approach, typically known as using a “carrot” or a “stick.” Common business incentives include an increase in compensation, recognition, or responsibility. That’s the “carrot” side of this equation; the “stick” side involves punishing someone for either doing or not doing something. (Pay is docked, participation in a project is canceled, or the highly anticipated business trip is withheld.) Rewards and punishments are largely considered coercive actions. The moment you remove the coercion (the carrot or the stick), the coerced individual regresses to previous behavior. Long-lasting career success requires real agreement, not a momentary nod.

Another age-old approach to attaining buy-in is through normative means, or via the “social norms” of a group—as in, all the kids are doing it. This is a difficult way to reliably achieve agreement because people are so mercurial. Today, you must be savvier than ever in your approaches to persuasiveness. And the savviest approach of all involves appealing to your target’s enlightened self-interest.

The concept of enlightened self-interest is largely attributed to the 19th-century French historian and social observer Alexis de Tocqueville and his landmark work, Democracy in America. De Tocqueville’s idea involves doing things that are positive and right (profitable and ethical, in other words). If it’s positive for you (your increased income, your heightened professional status, your strengthened organization), positive for other parties involved (your target and your target’s organization), and positive for the larger whole in which you operate (your industry or your community), then why not do it? Self-interest can be good; enlightened self-interest can be tremendous. Appeal to the enlightened self-interest of others, and prepare to hear yes again and again.

Congruency

Your external actions and internal thoughts must be aligned. I call this “congruency.” Years ago, a Harley-Davidson dealer wanted my help increasing sales of new motorcycles at his store. So I did what consultants do: I evaluated the market, employee skills, dealership processes, and the like. Improvements could be made, but something else was wrong. When I casually asked the motorcycle sales manager what he rode, he replied, “Oh, I don’t ride motorcycles. They’re overpriced and dangerous.”

Mystery solved.

If that sales manager didn’t support what he was selling, how in the world could he convince his salespeople—not to mention his customers? If you are promoting a product, an idea, or an initiative, you need to believe in it from an ethical standpoint. And even if we were to put the ethical issue aside for a moment, if you don’t believe in what you are talking about, your facial expressions and body language will give you away.

In 1966, two social scientists, Ernest Haggard and Kenneth Isaacs, filmed husbands and wives engaging in difficult conversations. Who manages the money? How should the kids be raised? All sorts of emotionally charged issues were discussed during these therapy sessions. During the exchanges, Haggard and Isaacs took notes on even the briefest facial expressions made by the couples and discovered what they called “micromomentary facial expressions”—commonly referred to today as “microexpressions.” Microexpressions last between 1/5 and 1/25 of a second and typically occur during high-stakes conversations when someone has something to lose or gain, and when at least one person is attempting to suppress his or her true feelings about something. Subsequently, the other person almost always senses this disconnect.

Several years ago, my wife, Amy, and I were in the market for a new television. We went to a store that shall remain nameless (big-box, yellow sign), where we selected a new TV. Amy looked on encouragingly as a blue-shirted employee and I wrestled the monstrous set onto a large industrial cart. We suddenly found ourselves surrounded by a gaggle of salespeople who apparently had just undergone stealth training. The leader of this group began touting extended service–plan benefits to protect our purchase. The newcomers nodded in unison, as if they were backup singers in a service-plan band.

Amy and I know and believe in the value of service contracts. We’ve helped Harley-Davidson Financial Services increase service contract sales for years. We always buy them for our Harley-Davidson motorcycles and often get them for our cars, computers, and iStuff. However, I treat interactions with salespeople as persuasion research, and I approach that task with the zeal of an archaeologist on the verge of discovering the Ark of the Covenant.

“I thought I just selected a fantastic TV. Why would I need a service plan?” I innocently inquired. The leader of the blue shirts stammered something about how the TV is not a divine creation and that manmade objects break. Another added an almost Stallone-like “Yeah.”

I hit them with objection after objection. After watching the blueshirted team sputter, struggle, and shift back and forth, trying to find answers they didn’t know, I finally revealed my background: “Guys, I help people sell extended service plans for a living.”

It was as if I had suddenly flipped on a light switch, and the cockroaches scrambled. We weren’t experiencing microexpressions, but rather macroexpressions. Those guys split. Almost immediately, Amy and I found ourselves alone with that gigantic TV.

Compare that exchange with one we had just days later shopping at a different retailer for a portable DVD player. After we had selected the brand and model we wanted, the young salesperson brought up the extended service plan. I could almost hear Amy’s eyes rolling, as she knew what was coming next. With the confidence of Babe Ruth in a Tball game, I began my research: “I thought we just purchased a great DVD player,” I said, using my familiar refrain. “Why would we need an extended service plan?” Again, I uttered objection after objection, building up to my big reveal: “Young man,” I said in my best Homer Simpson voice, “I show people how to sell extended service plans for a living.”

Without missing a beat, he exclaimed, “Perfect! Then you’re going to want the four-year plan.”

We bought the four-year plan. Why? Because that kid believed in what he was selling. His face showed he believed. His body language was open and energetic. And his voice sounded sincere.

This is why I always say the most fundamental persuasion principle is congruency: If you want to be convincing, you have to be convinced.

* * *

Continuing our story from the beginning of the chapter: Sally Matheson knew all about reciprocity. She understood what persuasion could and couldn’t do. She recognized the importance of having a healthy approach to organizational give-and-take. She also was convinced her initiative was good for the company, its customers, and Peter’s department as well as her own. And, as the multimillion-dollar project’s deadline loomed, she was convinced Peter Simmons felt the same way.

In his mind, Peter began replaying past experiences with Sally, much the way a high school graduation slideshow unfolds with Green Day’s “Good Riddance (Time of Your Life)” as the soundtrack. Peter remembered the time Sally went to bat for him on a controversial opensource programming idea, an idea that eventually became a big success—perhaps the greatest accomplishment of his career. He recalled how they worked together almost around the clock on a secret new product—project code–named “Thor”—only to be shut down in less than five minutes by an overly conservative board of directors. Peter and Sally had worked together, won together, and lost together more times than he could count over the past five years.

He looked at Sally again, who, in her tailored blue suit and matching Christian Louboutins, radiated as much professionalism now after almost 12 hours in the office as she did when she walked in that morning. “Well?” nudged Sally. “Do you have the energy to scale Kilimanjaro again?”

“For you?” Peter responded rhetorically, letting a beat pass to heighten the drama before breaking into a massive grin. “Yes. Unequivocally, yes.”

Chapter 1 Persuasion Points

- Peer-to-peer persuasion challenges can be the toughest and most frequently faced. So take a page from Sally Matheson’s playbook and comport yourself for the long term.

- Persuasion means “ethically winning the heart and mind of your target.” Think of influence as organizational horsepower.

- Persuasion has two primary roles: to get someone to willingly do something and to get someone to willingly not do something.

- The Persuasion Paradox: While persuasion is crucial to people’s success for many reasons, they actually spend very little time and effort improving their persuasion skills.

- To get the most from this book, you must set a persuasion priority. Who do you want to say yes, and to what?

- Persuasive people are assertive, empathetic, communicative, tenacious, and resilient.

- Reciprocity means “a cooperative interchange.” It’s the golden thread woven through almost all aspects of persuasion.

- The savviest professionals freely give and take.

- The oldest methods of getting someone to buy into something are reward, punishment, and normative means. But the most powerful method is enlightened self-interest.

- The ultimate persuasion principle is congruency. To be convincing, you have to be convinced.