CHAPTER 8

Persuasion 360

How to Get Agreement Up, Down, and All Around

Thus far, we’ve focused on persuading just one target. Now we’re going to turn our attention to persuading groups and specific members of groups. The first thing you need to acknowledge is that group decisions don’t get made in group settings. Think about that. It’s counterintuitive but inescapably true. Groups hear and discuss, sometimes debate and argue, but they seldom decide as a unit. Rarely will you find a single decision maker. Rather, multiple decision makers—often including, but not limited to, the budget manager, a hierarchical leader, and an informal leader—are involved in the final decision.

Thus, you need to appeal to fiscal prudence, leadership responsibility, charisma, or all of the above. Group meetings must be augmented by one-on-one meetings to gain support and woo true decision makers. Consider yourself a congressional lobbyist, but one with scruples and a good cause.

You don’t need unanimity or an overwhelming mandate to generate group agreement; you need critical mass. Consensus is something everyone can live with, not something everyone would die for. With that in mind, focus on the pragmatism of the numbers. That means “being right” in your own mind isn’t sufficient. You may have all the facts, all the right conclusions, but that still doesn’t mean your idea will become reality in a group setting. You must be cajoling and politically savvy; you must “work” the system, just as you would “work” a room when you’re networking. You don’t want to meet everyone, just the people who can help you the most. (A politician wants to convince every voter to vote for him or her but is most interested in those voters who can deliver—through their own influence—thousands of additional votes. Hence, a union officer is more attractive to a politician than a union member.) This is the kind of persuasive thinking that must go on in your head all the time.

WHERE PEOPLE STAND DEPENDS ON WHERE THEY SIT

Group targets who are idealists will try to tell you how the organization should work, while those who are pragmatists will tell you how things actually do work and how best to leverage that reality. American presidents Bill Clinton and Ronald Reagan were pragmatists in office, while presidents Jimmy Carter and Barack Obama were idealists. The differences in legislation passed and congressional support during their terms are overwhelming.

Groups are not sentient creatures as an entity but comprise sentient creatures. The legal and marketing departments will have different views on your pitch than, say, the R&D and finance departments will. (Inevitably, the human resources staff will always present alternate views and be the so-called odd man out.) Where others stand on an issue depends on the professional background they bring to the discussion and the impact that yes will have on their jobs, ranks, or careers.

One of the weaknesses of group influence is that the task takes much longer because of such dynamics. You have to stay the course and, in some cases, outlast opponents who will eventually be transferred, promoted, retired, terminated, or otherwise obscured or overruled. Sometimes no other way exists, so be prepared for a long-term persuasion arrangement, if necessary, in which you’ll need to create allies who recognize how they can prosper from your ideas.

SELF-TEST: WHAT IS YOUR PERSUASION IQ?

Horsepower. Pull. Sway. These words should be used to describe your organizational Persuasion Influence Quotient (or “Persuasion IQ”). (As covered earlier, I consider “persuasion” to be an action and “influence” to be a state or a condition.) Influence reflects the ability to create an effect without exerting an effort. The ability to persuade up, down, or all around depends significantly on your influence—and, frankly, has precious little to do with your title or ranking in the organization. How do you measure up?

Evaluating Your Skill Sets

Following are 11 ways in which you can evaluate your Persuasion IQ. Don’t overthink your answers, and don’t search for surgical precision. Just answer the questions, completely and honestly.

1. Do others in your organization regularly ask for your opinion?

Never Sometimes Often

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10

2. Have you been asked repeatedly to present your ideas, projects, or results to your organization’s senior management? (And, no, if you are a senior manager, talking to yourself does not count.)

Never Sometimes Often

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10

3. Have you been cited in outside media for your positive contributions?

Never Sometimes Often

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10

4. Have you been asked to speak to industry trade groups?

Never Sometimes Often

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10

5. Are you invited to weigh in on future company initiatives?

Never Sometimes Often

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10

6. Have others asked you to informally mentor them?

Never Sometimes Often

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10

7. Do your peers repeatedly use you as a sounding board?

Never Sometimes Often

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10

8. Have you been formally asked to play a role in your organization’s leadership development?

Never Sometimes Often

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10

9. Are you actively involved in the design and execution of company or work group policy?

Never Sometimes Often

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10

10. Are you invited by powerful people in your organization to get together socially?

Never Sometimes Often

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10

11. Do you believe that people speak about you in an overwhelmingly positive way when you’re not present?

Never Sometimes Often

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10

Interpreting Your Results

Add up your score, and divide by 11. This is your Persuasion IQ score.

1–3: Your Persuasion IQ is Low.

3–6: Your Persuasion IQ is Medium.

6–8: Your Persuasion IQ is High.

9+: Your Persuasion IQ is Superior.

Does the title on your business card have something to do with your organizational pull? Of course it does. But it’s not the most powerful factor. People who rely on their position for their power base typically don’t enjoy great careers, which is why no matter where you are in your organization (or even if you are an entrepreneur), this test can help determine the way to get more sway.

SEVEN WAYS TO “INFLUENCE UP”

Your ability to influence multiple targets will take many forms, requiring you to “influence up” (your boss, shareholders, a client’s president) and “influence down” (an outside organization, a temporary aide, a contracted employee). First, I present to you seven ways to influence up (which, incidentally, work well in individual persuasion situations, too):

- Speak the language. How do your targets view their work and their environment? Do they talk about market share, Return on Investment, Return on Equity (ROE), risk mitigation, competitive advantage, Market Intelligence (MI), shareholder value, stakeholder opinion, media response, or global presence? Make sure to cast your arguments in your targets’ language; interpret your goals for acquiring increased development funds in terms of higher market share and make a case for achieving a strong ROI in a brief time span.

- Deal with evidence, not opinions. Assemble the facts and remember that we’re talking about rules, not exceptions. Frequency of occurrence helps support facts and separate anomalies. Make sure your points are evidence-based and as unassailable as the rule.

- Find workable approaches. As stressed previously, don’t threaten people with an inquisition. Seek ways to rectify and reconcile so that everyone finds the solution salutary and satisfying. “Witch hunts” do not encourage people to emerge in the daylight with facts and suggestions.

- Be concise. Don’t tell people everything you know; tell them only what they need to know. (Otherwise, this book would be 5,000 pages long—to my editor’s considerable chagrin!) You need your targets’ attention, not their captivity. So ensure that you can succinctly state your case in the allocated time. Some people actually articulate their cognitive processes by “thinking out loud.” This horrible practice wastes time and diverts attention. Which brings us to . . .

- Manage the clock. If you end a meeting 10 minutes early, nobody is going to complain. But if you run over the allocated time by 2 minutes, people will rapidly lose interest—even if you held their undivided attention 3 minutes ago. To avoid that, work backward, allowing the final 10 minutes of a designated time frame to be used to develop consensus, determine next steps, set times and dates, and assign accountabilities. These are busy folks, with other places to be and people to see.

- Stand your ground. Maintain the courage of your position, meaning that while you should remain open to other views and even criticism, don’t back down in the face of strong opposition or peer pressure. People are most prone to follow formal and informal leaders who can both take the heat and lead the way through ambiguity and resistance.

- Relish being the contrarian. “Yes men” are abundant in organizations—don’t forget, we’re talking about group persuasion here—and they always attempt to side with the status quo to remain in the boss’s good graces. If you want to truly succeed at persuasion, be willing to stand out and be identified as someone with ideas that don’t adhere to the overused slogan, “That’s how we’ve always done things.”

These best practices to “influence up” are based on boldness and brevity, which strong senior people tend to appreciate and respond to positively. Remember that the people with whom you are dealing in group persuasion environments are paid to achieve results, and the quickest, most obvious road to that success will strike harmonious chords. So make your case in their language with an outcome-based focus in as brief a time as possible.

When Consensus Is Overrated

Sometimes the most compelling path to persuasion isn’t via group buy-in. In fact, dissension in the ranks can establish you as a bolder leader.

Leaders are paid to achieve results. Period. They often, therefore, must make tough decisions—decisions that others might shy away from or try to drown in a group setting. U.S. Army General Dwight D. Eisenhower didn’t call a meeting before launching the D-Day invasion of Europe, and US Airways pilot Chesley “Sully” Sullenberger III didn’t ask permission from the control tower prior to landing Flight 1549 in the Hudson River after geese disabled the engine power.

In other words, leadership doesn’t happen by committee. When the situation warrants, you need to make the tough call. So the next time you’re in a meeting and consensus over your ask seems unforthcoming, be the voice of reason for the group and render a decision that you know will result in the right outcome. You lead by creating results from which the majority will benefit—even if the majority doesn’t agree with you at that moment.

SEVEN WAYS TO “INFLUENCE DOWN”

Now let’s look at the opposite of influencing up, which is “influencing down” the hierarchical ladder. You don’t want people merely following orders or feeling coerced, because you’re likely to attain compliance but not commitment. Instead, you want enthusiastic supporters who demonstrate innovation and passion for their work and the outcomes. Here are seven ways to influence down (which, like those for influencing up, also work well in individual persuasion situations):

- Use your “home field advantage.” As mentioned previously, your office is the perfect place to persuade, especially if you and your targets are surrounded by your honors, awards, and diplomas—which subtly show the power of your position. Showcase your authority and remain more comfortable than anyone else in your own surroundings. (Obviously, if you work in a cubicle or you’re pitching to a large group, you’ll need to find an alternate location. In that case, a neutral space, such as a conference room or an off-site location, might work best.)

- Avoid condescension at all costs. Treat everyone as a rational adult by never implying a concept or topic is above someone else’s “pay grade.” Keep your voice confident, low-pitched, and professional, and avoid “up talk” at the end of sentences (ending the sentence on a higher pitch than you began, making declarative statements sound like interrogatives).

- Be brief but not abrupt. Take time to entertain questions. Pay as much attention and invest as much time with this process as you would if you were influencing up. Don’t expend less energy on these folks simply because they have lesser positions.

- Leverage honest ingratiation. In other words, sweet-talk your targets: “Your team has an exceptional track record with this marketing campaign, and I’d like your support in taking the initiative to the next level, because I know you guys can handle the added responsibilities.” If you’re honest and sincere, this is a fine tactic. If you’re neither, then it’s merely manipulative and will be unethical, ineffective, and perhaps even counterproductive.

- Request input. Don’t just ask for positive feedback, but invite negative comments, too, about what weaknesses your targets can detect in your pitch: “What do you see as the main vulnerabilities of this marketing plan?” It’s far more effective to elicit views regarding both sides of the issue rather than blindly believing your idea is perfect (or at least the only option).

- Provide opportunities for contributions. The majority of people would prefer to have control and influence over their work than regular pay raises, so explore how latitude of action and independence could help sway opinion: “We need someone to organize the database, work with the agency on calendar issues, and write the sales force communication. Which of these tasks would you most prefer?” In fact, application of talents and recognition for accomplishments are two of the primary motivators in the workplace. Why? Because people love autonomy. Incorporate that need into your plans whenever possible as another way of appealing to others’ self-interests.

- Don’t micromanage. I call this approach allowing “freedom with fences.” You delegate to subordinates all the time with the intent of reducing your own labor intensity, and the same dynamic applies here. Set aside some time to provide feedback, of course, as well as monitor and fine-tune results, while still remembering that autonomy often drives employees. (Feedback isn’t necessarily something all employees want, but it’s something you should know they need.)

FIVE WAYS TO “INFLUENCE SIDEWAYS”

Well, now that we’ve addressed your supervisors and subordinates, one last group of targets remains: your peers. This is known as “influencing sideways.” Peer pressure is among the strongest of all propulsions in the workplace (and elsewhere). How can you leverage it? Here are five ideas:

- Cultivate favors by doing favors. Remember the scene in The Godfather where Don Corleone agrees to help the undertaker handle an issue with his daughter, and then calls upon him much later for a return favor with a dead body? You can make people an “offer they can’t refuse,” because they are obligated to you. But this requires you to do well by others first—creating, say it with me, re•ci•pro•city. A quid pro quo. Whose quid and whose quo can be worked out later. People respond to obligations.

- Link agendas. By this, I mean that you should strive to forge common goals in an attempt to initiate persuasion. Employees at a tech start-up, for example, might think they serve two very different customers: the hardware providers and the end users. But there clearly exist areas of overlap, such as eye-popping graphics and the goal of seamless integration. Find the common areas of fulfillment with peers to then share ideas and resources. These may involve people, money, information, or facilities. The cost to you is minimal; the effect, potentially substantial.

- Leverage loss aversion. This may sound harsh, but leveraging the aversion to loss is a key factor in navigating peer pressure. Helping peers feel protected from loss of status, talent, income, and market opportunities can significantly impact on your desired outcome. Allow people to see that your intentions are comforting, not threatening, and they’ll remember.

- Covet your credibility. The fastest path to yes within all of this is your credibility. The more your peers can rely on your past behavior, track record, honesty, and commitment, the more likely they will be to accept your claims, offers, and pitches. Trust wins the day when your peers have experienced positive outcomes with you in the past.

- Be fair. Ensure that, in reality and in perception, the support you seek is not unilateral. Make it clear and obvious that no one (most important, you!) is taking advantage of anyone else. Insist on establishing a win-win dynamic.

DEALING WITH DECEIT

Give others the benefit of the doubt until proven otherwise. This will allow you to be sure your suspicions are not motivated by envy or otherwise. Don’t be paranoid, either. People who don’t jump on your bandwagon early aren’t necessarily opposed to your pitch; they just may not appreciate the wagon yet.

Occasionally, some people do think only of themselves and attempt to thwart your persuasion efforts for self-aggrandizing reasons. They take credit for what’s not theirs, manipulate others, and seem concerned only with personal advancement. They could act in a passive-aggressive manner by seemingly taking your side but then constantly undermining you through faint praise and nuanced critiques.

When that happens, control your emotion. Deceitful people can offend your sense of judgment to such a degree that you’re motivated to go head-to-head with them on an issue in a public setting. Don’t. That’s what they want you to do (because most of them are pragmatists, not idealists). A public—or at least an office—feud, whether you win or lose, will delay and often derail your persuasion plans. Most feuds simply meander on interminably, with no resolution and with others rapidly losing interest or at least feeling uncomfortable in group settings. Additionally, your opponent is likely skilled in the art of deception and will turn public conversations around as if to question your intentions.

One effective strategy against feuding is containment. Keep other options in your pocket to accomplish tasks without opponents’ input. Isolating their opposition or foot-dragging to minor issues, while gaining momentum on the major elements of your persuasion effort, will allow you to make necessary headway—much like the army that maneuvers around a single island of resistance on the way to its ultimate goal.

Another option is to shine a spotlight on the deceitful. In meetings with others, ask the deceiver to discuss his concerns. While it’s easy to be deceitful, it is much more difficult to present facts and figures to defend the deception. This is why group meetings play an important role in honest persuasion exploration. A final option is to not wait for the deceitful person to place his agenda items at the end of the meeting, because he knows that’s when the rubber stamp comes out and people are eager to move on. If you are able to move those items higher up on the agenda, you will control the conversation.

And once you control the conversation, you’re that much closer to obtaining agreement from groups.

NAVIGATING THE POLITICAL TERRAIN

If you want to dramatically improve your ability to persuade groups of people, you must learn how to wrap your head around two key words: organizational politics. If there are two words that evoke stronger disdain from professionals in organizational life today, I’ve not encountered them. But one man I met early in my career enabled me to rethink organizational politics. The late Joel DeLuca received his Ph.D. from Yale University in organizational behavior, led organizational development initiatives at companies that eventually became known as Sunoco and PricewaterhouseCoopers, and taught leadership at the Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania. In 1992, he wrote Political Savvy: Systematic Approaches to Leadership Behind-the-Scenes (Horsham, PA: LRP Publications), and in 2000 he taught me how to map the political terrain of an organization so I could achieve my persuasion aims.

Now I’m going to teach you. (Hint: It helps to have a map.)

Mastering Political Territory Mapping Techniques

One of the challenges when trying to bring a group of people on board with an initiative is the seemingly overwhelming amount of information exchanged. Who said what to whom at what meeting? How entrenched are his or her positions? Who knows whom, and who thinks what of whom? Let’s face it. Most organizations would make a great setting for a television soap opera. But you don’t have the time, energy, or resources to sit back and watch the ever-evolving Days of Our Office Lives play out. You need a picture of the political landscape in front of you. Welcome to Joel DeLuca’s Political Territory Mapping technique (or what I refer to as “Persuasion GPS!”).

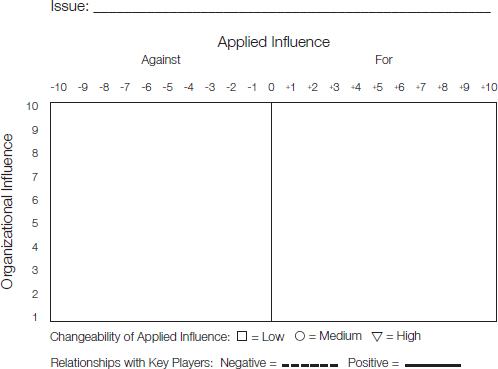

Looking at the top of the map (Figure 8-1), you’ll see “Applied Influence,” which is subdivided into two sides: “Against” and “For.” Across the top are degrees of “against-ness” and “for-ness.” When filling this out you won’t need surgical precision; your best guess will suffice. Have your targets demonstrated stridently and publicly that they are against your idea? If so, you might rate them as −8, −9, or even a −10. If, on the other hand, some of your targets have been leaning toward supporting your idea all along but need a bit more information before they’re completely convinced, place them on the “for” side somewhere between +3 and +5.

The axis identified on the left side of the map asks you to evaluate your targets’ “Organizational Influence,” or organizational horsepower. Again, no need for pinpoint accuracy; just a decent approximation will get you there. Next, outline what DeLuca called “Changeability”: What is the likelihood that your targets will change their minds—low, medium, or high? You will indicate that by simply outlining each player’s name in the appropriate shape. Finally, evaluate any unusually positive relationships with a solid line and any unusually negative relationships with a dashed line. Voilà! Now you have an effective snapshot of what you’re facing.

TRANSFORMING THEORY INTO PRACTICE

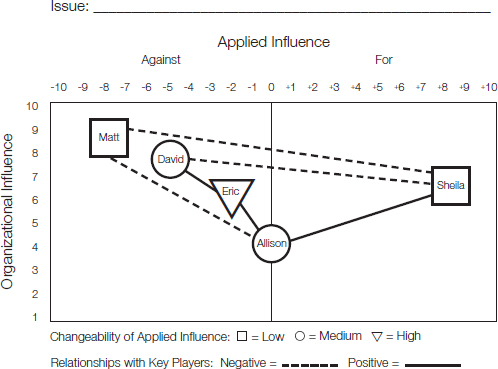

Now, let’s see how this map works by reviewing the office politics at a fictional software company called Retail Solutions, Inc. Let’s say the president has appointed a new marketing director, named Sheila. He didn’t run his plan by David, the marketing VP, prior to the appointment; he just placed Sheila in the position (sometimes colloquially called a “slam dunk”).

She’s now eager to prove to the organization that she’s competent and deserving of the position, and she has some radical new ideas in terms of software products. Because the president pulled executive privilege to secure the appointment, Sheila’s not without ample horsepower. But not many employees in the organization know or trust her (though an attorney named Allison works well with her).

A major retailer already wants the new software Sheila has proposed, but appeasing that client would require crashing project timelines. Sheila pushes hard for the organization to put everything on hold to support her project and this huge opportunity—requiring enormous sacrifice and risk for the organization.

Few in the organization are in favor. Matt, the director of software design (and the organization’s 800-pound gorilla), distrusts Sheila, because one of his greatest software projects was destroyed as a result of “crashing.” To say he is against Sheila’s proposal to crash the project is like saying Boston Red Sox fans have a slight disregard for the New York Yankees.

David thinks the hurry-up required will unfairly take budget dollars from other, more deserving projects, but he’s reasonable in his position. David has been employed by Retail Solutions for a long time and has close ties to the CFO, Eric, who also is leaning against the project. Either way, both of these guys pull considerable sway in the organization. The only person not publicly against the project is Eric’s trusted colleague Allison (the attorney), but she’s so consumed with improving the reputation of the legal department that she’s staying out of this debate.

Yikes! Now that’s a mess. At least it is until you apply the Political Territory Mapping approach. Then it looks like the map in Figure 8-2.

Although not a Persuasion Action Plan yet, the map does cut through the organizational noise and enable you to view the landscape within which you are operating. From here, if you follow the positive relationships and speak to others’ enlightened self-interest, you have the beginning of a Persuasion Action Plan.

To finish our story, Sheila put the map to good use. She leveraged her tight relationship with Allison to sway Eric and David to see things her way—and that, in turn, snowballed into such power momentum that she got the green light on her project.

The map is a terrific tool and can substantially reduce the time and energy it takes for you to separate the organizational wheat from the chaff. It focuses attention, identifies critical relationships, and enables you to test your assumptions with other politically savvy–minded people.

Are there caveats? Sure. The map is static. It’s just a snapshot of your ever-moving organization. Also, sometimes numbers give the impression of accuracy. Joel DeLuca used to joke about engineers going to three decimals in terms of evaluating someone’s organizational horsepower. (“She’s a 7.765!”) But just because you’ve done that doesn’t mean your evaluation is any more or less accurate. It’s still an approximation based on your own judgment.

Be careful not to overuse the map; this technique should be employed only occasionally and for big issues—not for deciding where to go for lunch. There also is the issue of confidentiality. You may use Political Territory Mapping with a small cadre of people who are close to you, but you wouldn’t post the map in the cafeteria. Regardless, the strengths greatly outweigh any weaknesses. Mapping allows you to develop persuasive strategies in half the time, think beyond the obvious, and bypass some of the organizational white water.

The map isn’t a hammer you’ll use every day, but it should definitely be in your toolbox. Having the ability to get agreement up, down, and all around is the ultimate skill for any persuasion professional. Practice the techniques presented here and you will be a persuasion professional par excellence.

Chapter 8 Persuasion Points

- Remember that group decisions don’t get made in group settings.

- You must influence up, down, and sideways.

- Focus on solutions and admirable goals.

- Consensus does not mean unanimity.

- Treat everyone equally—as rational adults.

- Some people can be convinced, while others can help convince several people.

- Use reciprocity and obligation when persuading groups of targets.

- Prepare for the occasional deceitful opposition by asking for supporting evidence and controlling the conversation.

- Learn and use Political Territory Mapping so you can clearly see the direction you need to travel to get group agreement.