Chapter 14

Using Communication and Leadership Skills When Managing Projects

In This Chapter

![]() Evaluating a project’s success

Evaluating a project’s success

![]() Understanding why projects fail

Understanding why projects fail

![]() Going through the steps of the project management process

Going through the steps of the project management process

![]() Communicating with stakeholders and the team

Communicating with stakeholders and the team

Projects are initiatives that a firm undertakes as a one-time effort — a unique sequence of tasks such as building a bridge, designing a car, or developing a computer operating system. The circumstances and requirements to complete a particular project and how the activities interact with each other are, at least to some extent, different from any other project. This uniqueness means that the people involved in a project do not have prior experience that tells them what to do, when they need to do it, and whom to coordinate with to get the job done. Therefore, the first responsibility of managing a successful project is leadership and coordination.

Management must lead the project by communicating the overall goals of the project, what activities each person involved must do, the limits of their authority, and when they need to act. Coordinating all this activity so they come together successfully to achieve the desired result is a fundamental responsibility of project management, too.

Statistically, the odds of achieving a successful outcome at the conclusion of a project are slim. Most projects don’t ultimately meet their objectives. Research in various industries — ranging from buildings and bridges to electronics and software — consistently reveals that about three of every four completed projects are late, over budget, or both. This dismal news doesn’t even account for the fact that many projects are never even actually completed.

In this chapter, we describe what defines success for a project, point out why projects fail, and show you how disciplined management through documentation and strict adherence to standard project management processes can ensure that your project is on time, on budget, and meets its requirements. We then focus on two other pillars of good project management: defining explicit goals of the project and communicating with project stakeholders.

Defining Success

Unlike processes, you don’t perform projects over and over again; they’re usually one-time efforts. The metrics of success for any project depends on the objectives that the project is intended to meet. Yet many project leaders spend far too little time before launching a project figuring out what they want to achieve. In some cases, this failure is a matter of interest; other times it’s due to a lack of tools and resources.

When initiating a project, you need to figure out ahead of time what needs to be done, how much it’s likely to cost, what kind of time frame the effort requires, and how you can track the project’s progress toward its goals. In this section, we present the most helpful criteria for launching a project plan.

![]() Scope: What exactly is the project supposed to accomplish in terms of goals and deliverables? And, maybe more important, what is it not trying to accomplish?

Scope: What exactly is the project supposed to accomplish in terms of goals and deliverables? And, maybe more important, what is it not trying to accomplish?

![]() Timing: How long will it take to complete the project?

Timing: How long will it take to complete the project?

![]() Cost: How much money will it cost to finish the project?

Cost: How much money will it cost to finish the project?

![]() Quality: What does the project need to do well to achieve its goals?

Quality: What does the project need to do well to achieve its goals?

Prioritizing criteria

How important each of these criteria is to a particular project depends on the project. If you’re planning the construction of a new stadium for the Olympics, missing the deadline by a week is a disaster. If you’re planning the construction of a new playground by volunteers in a neighborhood park, missing the deadline by a week isn’t such a big deal. (After all, you get what you pay for!)

Similarly, missing the cost budget for an Olympic stadium by 50 percent may not be disastrous. For example, the Sydney Opera House is considered one of the great architectural wonders of the 20th century and is a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Its original budget was $7 million. When completed, it ended up costing approximately $100 million. Thus, it was over budget by a factor of 14 times. While many complained about the overruns at the time, there was no rioting in the streets. On the other hand, overshooting the budget of a playground by a factor of 14 times just couldn’t happen because the project would be cut down or abandoned if costs ballooned to this degree. More important, you may never be invited to another neighborhood block party!

Quality is different from cost and timing. For starters, it’s not as easy to measure (see Chapter 12). Yet its impression is usually longer lasting. For example, Australia has mostly forgotten its cost and timing issues with the Sydney Opera House, yet it constantly trumpets the quality of the structure in terms of beauty and acoustics.

The point is that people often worry about cost and timing more than quality in the short run, but in the long run, quality becomes much more important.

We’re not suggesting that you plan on missing any of your project’s goals or success criteria. But realistically, if you have to trade off one criterion for another, be very clear which of them is more important, and be aware that this answer may be different in the long term versus the short term.

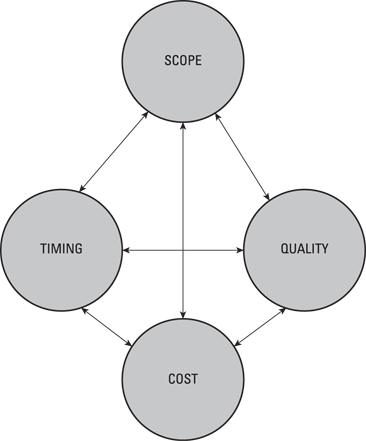

Seeing the interaction of factors

Bear in mind that the four factors for success (scope, timing, cost, and quality) interact and trade off against one another. For example, you can usually speed up a project if you’re willing to spend money on overtime and extra personnel. Similarly, you can always skimp on quality or scope to reduce cost or accelerate timing.

The project pyramid in Figure 14-1 shows the interrelationships among scope, cost, timing, and quality. For example, if you’re willing to give up on building that third wing to your Hollywood mansion, your project costs are likely to go down.

At the start of a project, its cost, timing, and quality (and even scope — as that often changes during the project) are estimates. Some folks argue that the reason many projects are late or over budget is because upfront estimates are too optimistic. Though this is certainly true in many cases, a reason that estimates are done poorly in the first place is because not enough effort was spent planning out the goals of the project. Thus, planning and goals are tightly interlinked.

Illustration by Wiley, Composition Services Graphics

Figure 14-1: The four project success factors.

Figuring Out Why Projects Fail

There are literally dozens of studies on why projects fail. Most of them concentrate on why projects are late or over budget, because these factors are the easiest to measure. However, our own research indicates that failures in quality and scope seem to have the same root causes.

The root causes for most project failures come down to the following five issues:

![]() Insufficient front-end planning: Particular problems include poor project definition, unrealistic project plans, poor cost/timing/quality estimates, and insufficient contingency planning.

Insufficient front-end planning: Particular problems include poor project definition, unrealistic project plans, poor cost/timing/quality estimates, and insufficient contingency planning.

![]() Poor scope control: Scope is what the project includes and — just as important — what it doesn’t. Scope problems are the great bane of project managers. Causes include poor project scope definition upfront and changes by the customer and/or the project management team.

Poor scope control: Scope is what the project includes and — just as important — what it doesn’t. Scope problems are the great bane of project managers. Causes include poor project scope definition upfront and changes by the customer and/or the project management team.

![]() Staffing problems: Turnover of key individuals derails countless projects. If your project can’t survive a member of your team dropping out, you have a problem. Another related issue is not bringing the right people with the right skills in on time.

Staffing problems: Turnover of key individuals derails countless projects. If your project can’t survive a member of your team dropping out, you have a problem. Another related issue is not bringing the right people with the right skills in on time.

![]() Technology issues: New technology can create uncertainty in any project. The worst case is if you have a number of technologies that all depend on one another to succeed. In that case, your project is almost certainly bound for trouble.

Technology issues: New technology can create uncertainty in any project. The worst case is if you have a number of technologies that all depend on one another to succeed. In that case, your project is almost certainly bound for trouble.

![]() Weak progress monitoring: This includes, among other causes, an inability to track progress or detect problems early. Often, this is as simple as not having any agreed-upon checkpoints with your client and your suppliers.

Weak progress monitoring: This includes, among other causes, an inability to track progress or detect problems early. Often, this is as simple as not having any agreed-upon checkpoints with your client and your suppliers.

Some of these causes interact. For example, activities that a project requires are sometimes forgotten or improperly specified upfront. This guarantees that any status update regarding what percentage of the project has been completed is necessarily wrong because the number of activities being measured against is underestimated.

You can avoid many of these failure-makers by spending adequate time planning upfront in a disciplined manner using the tools described in this chapter and in Chapter 15.

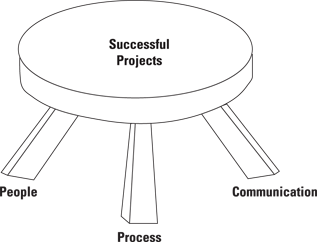

Laying Out the Project Management Life Cycle

Planning for a project can be a process, and like all processes, it benefits from standardization and discipline. A successful project rests on three legs, much like a stool (as shown in Figure 14-2). It needs

![]() Good processes to ensure that the appropriate actions are taken in the right sequence

Good processes to ensure that the appropriate actions are taken in the right sequence

![]() The right people working on the project

The right people working on the project

![]() Appropriate communication among project participants

Appropriate communication among project participants

Illustration by Wiley, Composition Services Graphics

Figure 14-2: People, process, and communication drive a successful project.

Projects are, by definition, a one-time series of activities. But there’s enough similarity among projects in terms of planning, communications, and coordination among the resources needed to complete them that a common process can help guide the planning and execution of a project through to a successful completion. This process is called the project management life cycle.

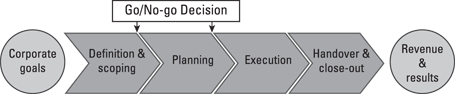

Detailing the phases of the cycle

The purpose of a project plan is to translate goals into objectives and results. Yet getting there requires adherence to a disciplined process. This process is laid out in Figure 14-3, which shows the four phases of the standard project management process. This same process is used for everything from developing space exploration projects to building bridges.

1. Definition and scoping. In this phase, you need to complete three primary tasks:

• Identify the goals and stakeholders for the project

• Write them up into a mission statement

• Make a first pass at identifying the timing, cost, technologies, and organization that the project requires to be successful

2. Planning. This phase requires a great deal of work, including these specific tasks, to enable successful execution of the project:

• Identify project specifications in detail (use quality function deployment, as described in Chapter 12, or some other method)

• Review lessons learned from prior projects that are similar

• Determine risks and opportunities and create contingency or mitigation plans as appropriate (see Chapter 16)

• Create a work-breakdown structure (see Chapter 15) to identify what activities need to be done and who is responsible for them

• Develop detailed scheduling and timing estimates (covered in Chapter 15) and establish progress milestones for later monitoring (see Chapter 16)

• Develop detailed cost estimates (covered in Chapter 15) and establish progress milestones for later monitoring (see Chapter 16)

• Assign resources, including suppliers to the project (see Chapter 10 for more on suppliers)

3. Execution. Now you need to actually do the project. In this phase, you handle these tasks:

• Monitor progress, cost, and quality of the project

• Activate contingency plans, if needed

• Manage scope change and creep

4. Handover and closeout. This is when you finish up:

• Hand over project deliverables to the client (this may involve some transition and training between you and your client)

• Ramp up to normal operation, if applicable

• Perform an after-action review to identify lessons learned

Illustration by Wiley, Composition Services Graphics

Figure 14-3: The project life cycle.

If you perform these four phases correctly, you should be able to achieve the desired results that were goals for your project.

Your ability to make changes in your project decreases as you move through the process. Figure 14-4 shows that as you move from definition and scoping to handover, the cost and staff level of your project progressively increases. Moreover, the dependence of your future work on past decisions increases as well. This makes the cost of changes more expensive as you progress through the project life cycle, particularly for those decisions that you’ve already spent money on.

For the same reasons, the ability of management and stakeholders to make changes to the project decreases. Changes that you can make with a simple line on a piece of paper in the definition and scoping phase can literally cost millions of dollars in the execution phase. Getting it right early in the process is crucial.

Deciding to go or not to go

Go/no-go decisions occur between the defining/scoping, planning, and execution phases (as shown in Figure 14-3). In other words, after you complete the definition and scoping phase, you may decide that the project isn’t likely to achieve its goals, which leads you to abandon the project. Companies often refer to these go/no-go decisions as stage-gates or phase-gates. Almost all companies use them.

Pulling the plug on a project may be a very good idea in some cases because you don’t want to throw good money after bad. Energy companies are known to spend up to $3 billion on a $10 billion project in the planning phase and then cancel the entire project. And this is okay! It’s much better to cancel a project after spending $3 billion than losing an additional $5 billion when your planning phase determines there isn’t enough oil in the ground to make the project profitable.

Illustration by Wiley, Composition Services Graphics

Figure 14-4: Project effort increases and management influence wanes over the life of the project.

Some companies have even expanded this idea to create competition in their planning process. For example, many electronic firms start 50 projects in the definition/scoping process each year, fully expecting to winnow that number down to 10 projects after the first stage-gate. After the planning phase, they expect to narrow that number down to 5 projects that they’ll actually execute. This Darwinian-style competition is sometimes called the project funnel; it’s used by firms in all kinds of industries — electronics, energy, movies, and many others.

Generally speaking, the likelihood that a project survives its next stage-gate is driven by its performance-to-date or by changes in the economic assumptions that made the project profitable. Thus, one would expect that many more highway construction projects should survive go/no-go decisions than should high-tech projects. In many cases, the decision-makers and project managers need to guard against falling in love with the project; this is the phenomenon that occurs when project sponsors emotionally can’t accept that assumptions and conditions have changed, and the project should be stopped.

Documenting the project

An important product of a well-executed project planning process is the set of documents that results from it. Formal documentation — so long as it’s not just a fill-in-the-blank exercise — benefits the project in a number of ways:

![]() It promotes alignment with the client and team members (assuming they read the documents; more on this in a bit).

It promotes alignment with the client and team members (assuming they read the documents; more on this in a bit).

![]() It prevents rookie mistakes that occur because a project manager forgets to do something important in the process.

It prevents rookie mistakes that occur because a project manager forgets to do something important in the process.

![]() It helps keep scope creep at bay by documenting exactly what is (or what isn’t) in the scope of the project.

It helps keep scope creep at bay by documenting exactly what is (or what isn’t) in the scope of the project.

One polite way to suppress scope creep from your client is to refer back to documentation showing that the new whiz-bang feature that your client now wants is indeed scope creep and can’t be completed on schedule or within budget. (Or, if you’re a consultant, documentation allows you to bill the client for these wonderful features with a minimum of fuss!)

Leading a Project

Successful projects require a leader who can coordinate a number of people from different organizations with different objectives and skill sets. Yet they need to work together toward the same goal to complete the project.

Have you ever watched a group of ants moving a piece of bread that’s many times bigger than any one of them? They can do this by working together and pushing in the same direction. Imagine if the ants all moved in different directions; the bread certainly wouldn’t make much headway.

Communication aligns the actions of the project team and coordinates the various project stakeholders. In this section, we describe tools you can use to manage project communication.

Developing a project proposal with a team

A common vision aligns the efforts of the people who are going to execute the project. One way of getting everyone on the same page is to develop a project proposal early on and refine it together over time. The project proposal should have the following elements:

![]() Purpose statement: This is a high-level description of the project and its goals. Think of it as the 30-second elevator pitch to sell your project. It should include these types of content:

Purpose statement: This is a high-level description of the project and its goals. Think of it as the 30-second elevator pitch to sell your project. It should include these types of content:

• An explanation of the business opportunity — why you’re doing this project

• Project objectives

• Expected benefits (both tangible and intangible) in rank order

![]() Scope: This encompasses what the project should include and exclude.

Scope: This encompasses what the project should include and exclude.

![]() Final deliverables not mentioned in scope (other than paperwork!).

Final deliverables not mentioned in scope (other than paperwork!).

![]() Rough estimate of cost and timing: A firm may require other specific metrics such as net present value, internal rate of return, payback period, and so on. (See Chapter 15 for details on how to estimate the cash flows necessary to calculate these common business metrics.)

Rough estimate of cost and timing: A firm may require other specific metrics such as net present value, internal rate of return, payback period, and so on. (See Chapter 15 for details on how to estimate the cash flows necessary to calculate these common business metrics.)

![]() Stakeholder analysis: We cover this later in the chapter.

Stakeholder analysis: We cover this later in the chapter.

![]() Chain of command for the project team and customer.

Chain of command for the project team and customer.

![]() Critical assumptions: Potentially critical obstacles and the impacts of violated assumptions.

Critical assumptions: Potentially critical obstacles and the impacts of violated assumptions.

Write the proposal for the entire project as if you plan on actually completing it. And use a cross-functional team of experts to develop it. Locking the team in a room for a couple of days to write the initial pass often yields the best results. If that’s not feasible, make sure you at least pass the proposal by all of your experts to get their input.

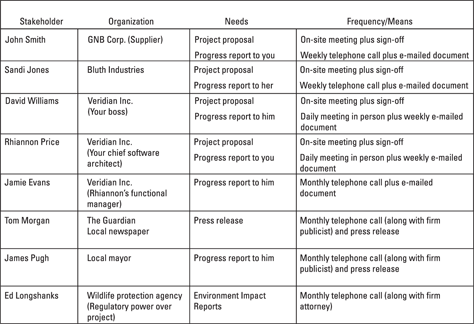

Communicating with stakeholders

A stakeholder is anyone with a stake in the outcome of a project or initiative, including anyone who can stop a project. Stakeholders can be internal or external. Internal stakeholders can include your executive sponsors, your project team members, and those team members’ functional managers. The customer and the customer’s management are always stakeholders, but whether they’re internal or external depends on whether they’re part of the same organization as the providers of the project.

Key suppliers may also be considered internal or external for various purposes, depending on how essential their participation is and how close your inter-firm relationship is. External public stakeholders include nongovernmental organizations (such as environmental lobbies or consumer safety groups), communities, and various government agencies.

Identifying stakeholders and communicating with them on a regular basis is critical to successful project management. If you regularly communicate with stakeholders and they’re satisfied with a project’s performance, then they’re less likely to riot when there are glitches, or when it’s late or over budget.

One of the first jobs of a project manager is to establish a communications plan. To do this, list your stakeholders (by name), their organization, what you need to communicate to them, how frequently, and by what means (phone, e-mail, visit, and so on). Figure 14-5 shows an example of some entries in a communications plan.

Illustration by Wiley, Composition Services Graphics

Figure 14-5: Sample entries in a communications plan.

Keeping stakeholders in the loop

You also must communicate with stakeholders frequently to manage expectations and prevent misunderstandings. You need to exchange formal documentation because it leaves a paper trail if misunderstandings occur, particularly regarding scope creep.

But don’t abandon phone and/or in-person communication because these traditional platforms allow you to highlight particular problems and to provide clarification that’s difficult to achieve on the written page (or even via e-mail).

Frequent progress reports are also essential. The amount of detail in your status reports depends on the size of the project and the preferences of the stakeholders in question. Moreover, you may want to manage some external stakeholders (such as public pressure groups) differently from others.

In medium-sized consulting projects (about $200,000 to $1 million of work), a weekly report may contain four elements:

1. What did we accomplish the prior week?

2. What do we intend to accomplish the next week?

3. What obstacles are standing in the way of completing the project, particularly for this next week?

4. How far along are we in the project versus where we expected to be?

Typically, answering these four questions is sufficient to keep the client in the loop and to deal with the most pressing potential problems.

Managing the team

Managing a team of employees or other types of doers in a project is much like managing other kinds of stakeholders. Upfront participation and frequent communication go a long way on the road to successful outcomes. And it’s crucially important to establish crystal-clear responsibilities upfront.

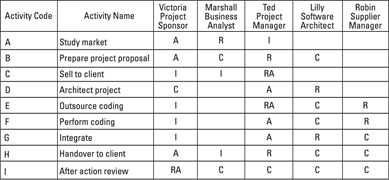

With an approved project proposal in hand, you can get the project rolling by distributing the proposal to all prospective team members along with a responsibility assignment matrix (RAM). Assign deliverables to people according to these four categories:

![]() Responsible: These people do the work to complete the activity. At least one R needs to be assigned to each activity. Often, you’ll have more.

Responsible: These people do the work to complete the activity. At least one R needs to be assigned to each activity. Often, you’ll have more.

![]() Accountable: These people need to sign off on the work of the people who are responsible for completing it. You should have exactly one A per task. A person can be both an R and an A on a task.

Accountable: These people need to sign off on the work of the people who are responsible for completing it. You should have exactly one A per task. A person can be both an R and an A on a task.

![]() Consulted: These are people who should be consulted. Typically, they’re sought out for expert advice on the activity or they’re responsible for related activities in the project.

Consulted: These are people who should be consulted. Typically, they’re sought out for expert advice on the activity or they’re responsible for related activities in the project.

![]() Informed: These are people who need to be informed on an ongoing basis about the project.

Informed: These are people who need to be informed on an ongoing basis about the project.

See an example RAM in Figure 14-6, and keep in mind that RAMs only work if the team members can actually see them! Be sure to distribute these documents to at least the people with an R, A, or C next to their names. No individual should have more than one letter next to his or her name for a particular task, except possibly RA.

There should also be a tight correspondence among the stakeholders, the communications matrix (as described in the preceding section), and the RAM matrix. In other words, if the stakeholders show up on one chart, they ought to show up on both of them.

Illustration by Wiley, Composition Services Graphics

Figure 14-6: Example responsibility assignment matrix (RAM).

Moreover, missing quality targets, such as falling masonry in a tunnel project, can literally kill people. Even smaller issues, like a persistent leaking in a roof, can sour clients on a project because, unlike late completion or cost overruns, poor quality continues to haunt the client on an ongoing basis — long after the project is completed.

Moreover, missing quality targets, such as falling masonry in a tunnel project, can literally kill people. Even smaller issues, like a persistent leaking in a roof, can sour clients on a project because, unlike late completion or cost overruns, poor quality continues to haunt the client on an ongoing basis — long after the project is completed. Check out

Check out  Project managers sometimes call a RAM a

Project managers sometimes call a RAM a