Chapter 16

Ten Pitfalls to Avoid

In This Chapter

![]() Avoiding too much focus on the short term

Avoiding too much focus on the short term

![]() Making sure the ‘soft stuff’ is on the agenda

Making sure the ‘soft stuff’ is on the agenda

![]() Ensuring appropriate up-front planning and preparation

Ensuring appropriate up-front planning and preparation

The journey to True North is unlikely to be entirely straightforward. En route you’ll encounter all sorts of potential diversions, barriers and pitfalls. This chapter describes some of the things that can so easily go wrong if you take your eye off the road and try to cut corners. So here we share our experience of observing many diverse organisations to help you avoid a bumpy ride.

Too Much Focus on Short-Term Objectives

Transformation is about fundamental and significant change in, and to, an organisation. It’s not something to be done lightly nor will it happen immediately. Transforming an organisation takes significant time and effort, and needs to be seen in that context.

The bigger the scale of change, the longer it takes. As benchmark examples, a rapid improvement or Kaizen event (refer to Chapter 12) may last a week, a Lean Six Sigma Green Belt project (also covered in Chapter 12) may take three months or more, and a product, service or process design/redesign may involve generational phases spanning more than a year. Of course, along with other actions, the transformation programme comprises elements such as shorter-term Lean Six Sigma projects, and their execution will be directly driven by short-term objectives. However, just as these may be elements of the larger-scale transformation programme, their corresponding short-term objectives are part of something bigger, collectively contributing to the longer term-strategic objectives and, again, need to be seen in that context.

While all longer-term strategic objectives need to be broken down into shorter-term tactical ones (refer to Chapter 8), not all short-term objectives necessarily relate to one of the vital few critical breakthrough objectives. Those that do should have been identified and aligned to them through the strategy deployment process.

Creating the right balance between longer-term strategic objectives and day-to-day operational objectives is crucial. Too much focus on the short term and the organisation will twist and turn with no regard for the longer-term direction, but without translating longer-term objectives into bite-sized shorter objectives and executing those, the company won’t move forward in a timely manner.

You have to continually deliver results within the context of the organisation evolving and changing over the longer term.

Strategies that aren’t Clearly Defined

Until you have to explain something to someone else, you don’t really know if you actually understand it. You can apply this truism to strategies, which must be clearly defined and communicable. Of course, a strategy also has to be appropriate and well-judged, but it’s unlikely to be either unless it’s completely understood by those who have developed it.

Defining a strategy particularly clearly will force you to review and reconsider it, check whether it’s complete and thought through, whether it links appropriately to other strategies and plans, and if you’ve forgotten to take anything into account.

You can ensure you describe a particular strategy in SMART terms (specific, measurable, achievable, realistic and time-bound) or you can use a strategy map to trace out (with quantified targets) how the strategy will link with other strategies to deliver key performance results. If gaps exist in the strategy linkage, the strategy has not yet been fully thought through and defined.

Unless a strategy is clearly defined it will be impossible to properly deploy it and the intended transformation will be impossible from the outset.

Not Enough Programme Planning

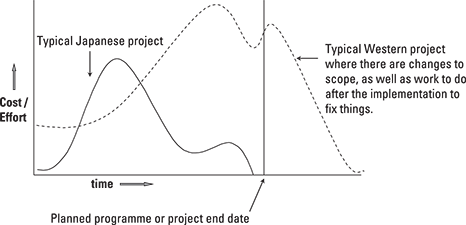

Figure 16-1 illustrates the difference between the traditional Western approach to projects and programmes (the dotted line) and the Japanese approach (the solid line). As can be seen, the Japanese put greater initial effort into programme planning.

Figure 16-1: Preparing for success by involving everyone from the start.

Although the Japanese approach (including strategy deployment) requires more effort at the beginning, it pays off over the lifetime of the programme or project. Without this intensive prior planning and preparation, progress initially seems to be faster and requires fewer resources. However, the deficiencies inherent in this approach catch up later and you’re likely to need significant rework and potential changes to the scope of the project. As a result, a disproportionate amount of resources is required to address and rectify problems and costs thus increase.

Making Assumptions about the Needs of Customers and Other Stakeholders

Listening to the ‘voice of the customer’ is one of the core principles of Lean Six Sigma. It becomes even more essential when you’re considering a programme of transformational change. Assuming that you know what customers (external or internal) want is all too easy, but unless you ask them you can never be sure.

Even a not-for-profit organisation has customers – stakeholders whose requirements are ultimately the reason for the organisation’s existence. A business organisation’s long-term survival and prosperity depend on the profits generated from the value it delivers to its customers. And a necessary condition for doing that is really understanding customers’ needs. Doing so consistently requires an effective dialogue with your customers.

Not Obtaining Process Ownership

A process owner takes responsibility for a particular process. They champion Lean Six Sigma projects to design or improve that process; commission, review and steer those projects; and then monitor performance and take corrective action as necessary to maintain that improvement. Collectively, the various process owners enable the projects comprising the transformation to be effectively identified and executed, and the overall change to be nurtured and subsequently sustained. Without obtaining process ownership, the transformation programme wouldn’t be supported effectively at the constituent project level and at least some of the projects would likely flounder. Given the tight alignment required for effective strategy deployment, the transformation programme may collapse if key constituent improvements no longer provide the basis on which to build the breakthrough change.

Ignoring the Soft Stuff

Many traditional Lean Six Sigma training courses and strategy deployment publications cover the ‘hard stuff’ such as the statistical techniques, the DMAIC methodology (refer to Chapter 1), the X Matrix (covered in Chapter 8) and the catchball process (also Chapter 8), not to mention an extensive array of other tools and techniques. However, they often don’t deal with the softer tools; the people issues that you need to gain buy-in and overcome resistance. Consequently, those new to strategy deployment (just as with those new to Lean Six Sigma) may try to run programmes and projects focusing on the tools and techniques rather than the people who need to enact them. Doing so can lead to a lack of buy-in from managers or operational staff, who either don’t understand or cannot accept the approach.

Leading and carrying people along with you are vital to the success of your transformation programme. Our years of business experience tell us that the really hard stuff is the soft stuff!

Assuming that No Response Means No Resistance to Change

Research suggests that for every customer who complains about something, perhaps ten or more others are silently dissatisfied. We have every reason to believe that a similar picture applies to the transformation process – for every person who actively challenges the proposed change many more still are silently resistant.

The biggest resistance to change is apathy rather than open rebellion, and for the transformation programme to succeed it needs to actively engage most people. Hopefully, some degree of simply passive acceptance shouldn’t derail it. Attitudes to change need to be actively managed, which requires management by fact not assumption in keeping with the principles of Lean Six Sigma. The bigger the scale of change, the more important actively engaging people becomes.

You can assess people’s attitude to change using simple tools such as stakeholder analysis and then seek to verify this picture through appropriate discussions with the groups involved. You need to establish whether silence means they’re simply ‘neutral’ on the issue or silent in expressing their disagreement.

For more on stakeholder analysis, see Lean Six Sigma For Dummies (Wiley).

Strategic Breakthroughs that aren’t Really Breakthroughs

Undertaking the strategy deployment of breakthrough objectives is challenging and time-consuming, especially if Lean Six Sigma is a new approach for your organisation. Deploying more than a very limited number of strategic breakthrough objectives at any one time thus isn’t practical, and to be effective and successful you need to focus on the vital few objectives. Don’t waste time and effort on those that aren’t really breakthrough objectives.

Ultimately success is all about focus. You need to concentrate on the really vital breakthrough objectives and getting those successfully deployed, executed and delivered. Achievement of these objectives is essential to the sustained future health of the organisation, and failure is not an option. Although the other objectives also need to be managed, they require less effort and attention.

Avoid chaos and overload – prioritise, focus and ruthlessly pursue the truly vital few!

Not Organising Monthly Strategy Deployment Reviews

Just because something has been planned doesn’t mean it will happen to plan. Lean Six Sigma stresses the importance of understanding and managing variation. In a similar way, variances from plan will occur for a variety of reasons, including:

- Imperfect, incomplete or delayed actions

- Off-track Lean Six Sigma projects

- Incorrect assumptions in planning

- Absence of key people

- Changes in the business environment, market or economy

- Competitor developments

Regular monitoring and review of progress is essential to identify such variances and promptly initiate corrective action if and as appropriate. Monthly review is a key component of the PDCA cycle (described in Chapter 8) inherent in the strategy deployment process. Strategy deployment isn’t just about planning; it’s also about review and corrective action. The tight alignment of objectives and actions secured initially through the planning element of strategy deployment needs to be retained, sustained and maintained, and the mechanisms for doing so are the monthly and annual reviews and resulting corrective actions. Without the discipline to regularly and routinely undertake the monthly strategy deployment reviews, you can’t expect to sustain the hard-won alignment.

Lack of Trained Lean Six Sigma Practitioners

The transformation programme will include many different elements tightly aligned through strategy deployment. Among these will be many Lean Six Sigma projects to design or improve individual processes to secure the required change or enhancement in performance. Other elements also benefit from the application of appropriate individual Lean Six Sigma tools and techniques. For all of these to succeed and deliver the planned improvements in a timely manner, the organisation needs a sufficient number of project leaders and team members with the appropriate skills and knowledge; that is, trained Lean Six Sigma practitioners. While you can engage consultants, the most cost-effective long-term solution is to develop a cadre of trained and experienced practitioners from within your own organisation.

Our experience tells us that many, if not most, organisations undertaking transformation experience a shortfall of trained and experienced staff. Surprisingly, we’ve also seen many organisations exacerbate this situation by letting go of key Lean Six Sigma practitioners when they scale up from an initial Lean Six Sigma programme to full-scale transformation and hiring external consultants to focus on the ‘new’ approach.

What you invest in planning right from the beginning pays off in spades throughout the transformation process.

What you invest in planning right from the beginning pays off in spades throughout the transformation process. Don’t throw out the baby with the bath water! The very skills you need to lead and support many of the projects may already exist within your organisation – so use them. If you discover you need more practitioners, first establish whether you have sufficient time and resources to train and develop your own staff before deciding to buy in skills and expertise from outside.

Don’t throw out the baby with the bath water! The very skills you need to lead and support many of the projects may already exist within your organisation – so use them. If you discover you need more practitioners, first establish whether you have sufficient time and resources to train and develop your own staff before deciding to buy in skills and expertise from outside.