CHAPTER THREE

STRUCTURING GOVERNANCE AND GOVERNMENT

The Layered Territorial and Bureaucratic Organization of the World

The territorial boundaries that crisscross the earth's landmasses do not represent cultural and economic boundaries. People, however, are very much inclined to think of, say, Argentinian, Australian, Canadian, Chinese, Egyptian, German, Indian, Israeli, and South African culture as something that is circumscribed by borders, thus almost equating culture and country. Within these borders people are governed by political systems shored up by bureaucracies. What seems the normal situation today really spread from a small part of the world across the globe only about 200 years ago, and it was not until after the Second World War that the earth became almost totally “administered space” (Scott, 2009; see previous chapter and below) and did so at an astonishing speed (Lefebvre, 2009, p. 96). Territoriality and bureaucracy are closely intertwined everywhere. Indeed, territoriality and dominance hierarchies are the two major features of social life in many species (Dawkins, 2006, p. 113). Except for the few city-states remaining (for instance, Monaco, San Marino) and for small island states (in the Pacific and the Caribbean), most countries are territorially layered from the local up to the national level. At each of these levels, bureaucratic organizations can be found that provide services and help elected officials to flesh out policies. It is common to think of territoriality and bureaucracy in relation to the state, but elements of both existed before the state did. In this chapter we will look closely at the development of territorial and bureaucratic organization over time, and we will see how the historical trend has been one of convergence toward the territorial (national) state with expanding bureaucratic organization at each jurisdictional level, and this is in part a consequence of the colonization of the world by a few European countries.

In Section 1 we will define and discuss features of territoriality in relation to property, thus setting up the framework within which we can understand the territorialization of the world (Section 2). Territorialization has both international and domestic elements. Internationally, it concerns the demarcation of boundaries between countries (Section 3), while domestically it is evident in a layered, nested system of subnational jurisdictions, i.e., a system of multilevel government. In Section 4 we will describe the historical development of subnational jurisdictions, while in Section 5 we pay attention to the contemporary situation. In Section 6 we briefly discuss bureaucracy as organizational structure and focus on its emergence and development over time and pay attention to the fact that bureaucratization is not something that is limited to large organizations. Indeed, one can say that society and the world have bureaucratized as well. (Nota bene: In Chapter 6 we will discuss Max Weber's ideal type insofar as it concerns organizational structure, and in Chapter 8 we shall outline those elements that concern functionaries.) While land has been territorialized, and while elements of bureaucracy have been around since prehistory, that countries around the world have settled upon a rather similar style of territorializing and administering their land requires a discussion of colonization (Section 7).

Territoriality and Property

Perhaps one of the earliest observations about the meaning of and relation between territory and property is that by Jean-Jacques Rousseau, which opens the second part of his discourse on inequality:

The first man who, having enclosed a piece of ground, bethought of himself of saying ‘This is mine’, and found people simple enough to believe him, was the real founder of civil society. From how many crimes, wars, and murders, from how many horrors and misfortunes might not any one have saved mankind, by pulling up the stakes, or filling up the ditch, and crying to his fellows: ‘Beware of listening to this imposter; you are undone if you once forget that the fruits of the earth belong to us all, and the earth itself to nobody.’ (1986, p. 84)

This is a very interesting observation. When people do not regard the earth as a property, it is simply a commons from which they take what is needed to survive. This is how most, and probably all, indigenous peoples “used” the earth and they still do so; to them the earth is not a property that can be bought and sold.

Rousseau's observation points to a commodification of the earth, and this happened when people shifted from nomadic to sedentary life, thus well before they started recording their activities. From Rousseau's remark we can infer that territorialization is a social act, for it is established in interaction between people. Second, it also suggests that people living in sedentary communities with a population size larger than what can be effectively monitored on a kinship and friendship basis will operate upon, at first, an implicit, later an explicit system of social stratification (Massey, 2007). After all, no one objected to that one individual claiming a piece of land as his property, and we assume this is because he was considered superior in some respect.

The most commonly used definition of territoriality is that by Robert Sack: “the attempt by an individual or group to affect, influence, or control people, phenomena, and relationships by delimiting and asserting control over a geographic area.” (Sack, 1986, p. 19) We find a comparable emphasis on “control” in the definition by Alan Buchanan and Margaret Moore: “. . . territory refers to the area or domain of jurisdictional authority of a ruler (in monarchical systems) or of the people who are conceived as sovereign (in democratic systems).” (2003, p. 328) The latter definition emphasizes that territory is not to be regarded as private property for two reasons. First, territory is the land where a community of people lives and since that territory is constitutive of that people'sidentity it cannot be treated as a commodity; that is, the community does not “own” the territory. In away this is reminiscent of how indigenous people view the earth as a commons. Second, private property can be acquired within a system of rules that is established by those in power, while territory circumscribes the area where those rules apply. Both these reasons apply to the sale or purchase of a territory. It is a somewhat different matter when territory is inherited; that is, when jurisdictional territory could be passed from one monarchical ruler to another or could be combined with other territories as in the case of dynastic marriage. To be sure, though, a ruler was not at liberty to simply cede territory (Buchanan and Moore, 2003, p. 330). That too underlines how territory cannot be treated as private property.

Territory is an important resource in the struggle for power and status and is therefore open to political manipulation. It also buttresses claims of authority, and the higher population density is, the more that existing patterns of authority will be reinforced (Merelman, 1988, pp. 579–582). Richard Merelman argues that authority is constrained by community, implicitly suggesting that authority travels top-down and is associated with the state while community functions bottom-up as it embodies localities (p. 586). Indeed, states compete with substate groups, communities, and individuals who seek some degree of control over land and resources (Peluso, 2005, p. 2), and they do so especially when local claims predate state claims (Wadley, 2003). States and their governments formally map territory, but these can be met with countermapping, which is when locals map village territories as they did in West Kalimantan, Indonesia. These countermaps became maps of power when authorized and used by regional and district authorities (Peluso, 2005, p. 12; for the importance of maps for defining territory, see Anderson, 2006).

In many places in the world formal jurisdictions represent a mix of state and local maps and practices, tying state and localities together. Once the rights to resources are territorialized and mapped or documented by the state, the state gains a certain power over those resources and the people claiming them. The state then manages the territory as eminent owner, superimposing its rights and power over the rights of locals. Henri Lefebvre suggests that centralizing state power results in neglect of the peripheries, the margins, the regions, the villages, and local communities. His autogestion or self-government denotes popular democratic control over spatial areas or jurisdictions (as discussed in Brenner and Elden, 2009, pp. 360–361). In a recent study the anthropologist James Scott argued how the great majority of humankind operated for millennia on the basis of self-governance. Zomia (from zo = remote and mi = people) was the name he gave to the mountainous regions of Southeast Asia that included parts of India, Burma, China, Vietnam, Laos, Thailand, and Cambodia. Until the mid-twentieth century the local communities in these remote mountains were able to resist the encompassing and invasive power of the state, removing themselves from the effective control of the state. Thanks to technologies that pretty much demolished geographic distance (rail, all-weather roads, telephone, telegraph, airpower, and information technology), ever-larger parts of the globe have come in the state's sphere of influence. By the second part of the twentieth century even the remotest territories were effectively incorporated in and by the state.

We mentioned previously that territory is an important source of power and status, so we must ask why rulers territorialize. Peter Vandergeest and Nancy Peluso provide three motives. First, rulers are interested in protecting access to people and income from taxes and natural resources, especially in a world where only territorial claims are regarded as legitimate. Second, territorialization allowed for improved efficiency in the collection of taxes, both in terms of volume as well as regularity. Third, at the same time, territorialization is only possible when there is a sufficient level of commercialization and increased ability to extract taxes on a regular basis, in order to pay a regular salary for the officials administering the territory through their bureaucracies (1995, p. 390).

A pattern of territorialization can be discerned, from small to larger territories, and this involves a variety of tendencies (the following based on Sack, 1986, pp. 32–34). First and foremost is that territoriality classifies a specific area or a location in space. The boundary is, second, often easy to communicate by means of markers or signs. Third, it is the most efficient way that rulers can exercise and enforce control. Fourth, given that territory is a source of power, it is a means to reify power. At the same time and when possible, rulers do not like to be seen as those who forbid, so territoriality, fifth, moves attention away from the interaction between ruler and ruled and directs it to “the law of the land.” Sixth, it also makes relations impersonal, clarifying who “belongs” where in the imagined communities of the past and today. Seventh, territoriality is also a neutral means to define place and make it permanent through property rights. An eighth feature is that it contains or shapes spatial properties of events, such as when a specific subnational unit receives national help in times of emergency. Ninth, territoriality also helps define empty space, such as an area without any socially or economically valuable features (e.g., a vacant lot in town). Finally, tenth, territoriality may help establish more territories.

The major historical trend is that the total number of territorial units has declined enormously since prehistory. Edward Deevey (1960; as referenced in Sack, 1986, p. 52) estimated that there may have been about 3 million people on the globe in the Upper Paleolithic (between 50,000 and 10,000 years ago) divided among some 100,000 or more independent, small units. After 10000 BCE the size of autonomous units increased, while at the same time each of these autonomous units became increasingly subdivided and fragmented into various types of territorial subunits. We shall see in Section 4 that territorial subunits became important from about 3000 BCE on.

Territorialization of the World

Territorialization is generally a slow process. We tend to think that it spanned many centuries in Europe and North America, and was accelerated elsewhere because of European claims on major territories in every continent (Vandergeest and Peluso, 1995, p. 391). But wherever people started living together in groups larger than those that could be “governed” on the basis of kinship and friendship, some type and degree of territorialization occurred. The one dominant for most of history is a somewhat loose or flexible territorialization, with people recognizing that they “belong” to a territory of which the geographic boundaries are flexible and subject to the consequences of migration. That is, when people “migrated or expanded to new territories, the boundaries often expanded or migrated with them . . .” (Vandergeest and Peluso, 1995, p. 394) Most important, geographic boundaries framed rules about and rights to resources for the people residing within. Today, the most dominant feature of territorialization is its inflexibility, especially with regard to boundaries between states.

Next to flexible and inflexible territorial boundaries, there are other differences between modern states and governments on the one hand and their premodern predecessors on the other. Before the modern era, the central feature of administration was that it was usually based on control of labor rather than of land, and this was expressed in at least three ways (Vandergeest and Pelosu, 1995, p. 392). First, political units before the modern era were identified and classified by ruler and ruling center, not necessarily by territorial boundaries. Second, if there were boundaries they were not communicated to the people by means of mapping the territory, but by defining access to the territory's resources. Third and related to the first element is that rulers used their coercive capabilities not to impose territorial claims but to demand labor (for instance, for the construction of large, monumental architecture), and/or the products of labor (as taxation in kind), and/or the lives of people (as in the case of conscription to military service).

There is a fourth element (based on Van Caenegem, 1967, p. 98) that involves the basis of law. For much of history people were judged according to the law of the tribe or community to which they belonged. This is known as the personality principle of law, and this meant that one could only be judged and punished on the basis of the law of one's own tribe. In other words, the influence of tribal law extended beyond tribal territory. This lasted in, for instance, the territories that today are France and Germany until the tenth century CE, and was slowly replaced by the territoriality principle whereby one was judged and punished on the basis of the law of the territory where the crime or transgression was committed. In this situation the law of a territory did not stretch beyond its jurisdiction. In the course of the nineteenth century the passive personality principle emerged, which is the situation where a country exercises jurisdiction over a foreign individual who harmed one of its citizens outside of its territory (see also McCarthy, 1989, pp. 300–301; Murphy, 2006).

How territorialization unfolded can best be illustrated by describing the situation at the dawn of history and then look at a real case, namely that of territories in Southeast Asia, and Thailand more specifically, since it captures quite well the situation in the world at other times and in other contexts (unless otherwise indicated, the following is based on Vandergeest and Peluso, 1995, pp. 392–401; and Scott, 2009, p. 36).

Scott made a convincing case when arguing that for most of human history the social landscape consisted of elementary, self-governing kinship units that every now and then cooperated in hunting, feasting, skirmishing, trading, and peacemaking (2009, p. 3). A good example would be the Wintu, a people living in northern California and engaging with surrounding tribal units, undisturbed until the 1830s–1840s (Chase-Dunn and Hall, 1997, pp. 126–148; Chase-Dunn and Mann, 1998). There is no reason to believe that this was any different in other parts of the world. Central to Scott's reasoning is the notion of self-government. He points out how the state-centric view in which history is reconstructed is a gross distortion of reality, only possible because the temporarily large concentration of people in a formal state left a much larger footprint (in terms of documentation, architecture, but also garbage) than the more mobile and egalitarian communities (Scott, 2009, pp. 32–34). In fact, as he reasons, history is replete with clashes between self-governing peoples on the one hand and expansionary states on the other. The states of ancient Egypt, Greece, and Rome, as well as the early Khmer, Thai, and Burmese states, were surrounded by vast, ungoverned peripheries that represented both a threat and a challenge (Scott, 2009, p. 6). The same clash is visible in the creation of supersized polities, such as the Chinese Han, Roman, Ottoman, Hapsburg, and British empires. And it is clearly present in the subjugation of indigenous peoples in Africa, Asia, the Americas, and Australia.

For thousands of years the basic political units in Southeast Asia included the nuclear family, segmentary lineages, bilateral kindreds, hamlets, larger villages, towns with immediate hinterland, and town confederation. More complex levels of integration were very rare and short-lived (Scott, 2009, p. 36). Peoples could easily support themselves through the active exchange of goods, people, and ideas; a political administration or “unified” territory was not necessary, as already pointed out by Fernand Braudel with regard to the Mediterranean (Scott, 2009, p. 48). Before the end of the eighteenth century the territory that roughly comprises Thailand today was sprinkled with hundreds of principalities, with each of its lords and kings paying homage to the king in Bangkok (Vandergeest and Peluso, 1995, p. 392). The farther from Bangkok, the more independent a territory was. Serfs and slaves were classified by category and by master rather than by residence (Vandergeest and Peluso, 1995, p. 393).

Was it any different elsewhere? We suspect not. In medieval Europe there were thousands of more or less sovereign units within the Holy Roman Empire, all officially acknowledging the authority of the Holy Roman Emperor but in practice quite independent. During the early Middle Ages and after the Romans departed, English localities and regions slowly coalesced into four kingdoms: East Anglia, Essex, Kent, and Wessex, which, under pressure of Viking invasions in the eighth and ninth centuries, united under the House of Wessex. Until the unification of France under one monarch, the French territory was nominally governed by one king, while regional dukes (those of Aquitania, Brittany, Burgundy, and Normandy) had the most power. This, then, was in the English, French, and German lands a feudal system of government that lasted from the sixth/seventh centuries well into the fifteenth century. While somewhat different, a comparable feudal system with many small centers of power could also be found in Japan between the twelfth and nineteenth centuries. Until the Norman invasion of 1169–1172, Ireland was ruled by five kings (those of Connacht, Leinster, Meath, Munster, and Ulster) under one high king.

Notwithstanding the general pattern and tendencies mentioned at the end of the previous section, there is quite a bit of variation in how these boundaries are set between countries and in how they are structured internally. How boundaries are set is particularly important in the international arena, and that will be addressed in the next section; how they are structured is more of a domestic issue, which is the topic of Section 4.

International Boundaries

Governing takes place in identifiable jurisdictions with natural (water, mountain range) and/or artificial (negotiated) boundaries. As we stated at the outset of this chapter, today almost all of the earth's landmasses are “administered space;” that is, belong to a specific country. The only land-mass that does not is Antarctica, which is governed through the 1959 Antarctic Treaty, which by now has 42 signatories (Jorgensen-Dahl and Ostreng, 1991). How were and are these boundaries set?

Before the modern period, boundary setting was mainly a nonlinear process whereby borders were established through conquest, settlement, inheritance, sale/purchase, and secession (this paragraph based on Buchanan and Moore, 2003, pp. 317–335). In the case of conquest, an aggressor simply invaded an adjacent territory for its resources and thus enlarged his own state and revenue. Historically, conquest has been the most dominant mode of boundary setting. Settlement was a situation where one state occupied waste or vacant land and colonized it. Indeed, settlement was the main method through which a few European countries managed to acquire large territories in other continents either by settling their own populations (as in the Americas, Australia, and New Zealand) or by governing territories elsewhere in the desire to civilize them (as in the case of colonization of Africa and parts of Asia). With regard to land, sale/purchase and inheritance are much less common since a country's territory as a whole is not private property. Finally, secession may be the outcome of a particular group's effort to change existing boundaries, and this has become more common in our own time. Secession may take the form of complete separation from an original sovereignty, such as the desire of some Québecois pursuing independence from Canada, of some of the Basque people who wish to separate from Spain, and of Scottish separatists who wish to leave the Union with England that was established in 1707. A less disruptive form of secession is the acquisition of some degree of autonomy within a jurisdiction, as is the case with, for instance, many of the British Commonwealth countries (that are independent but recognize the British monarch as the head of state) and with Aruba within the Dutch Antilles.

There are two important moments in the development of the contemporary practice of international boundary setting. The first is the Peace of Westphalia of 1648 that laid the foundation of the modern state system; the second moment is really a period, 1900–1945, when the basic stages of modern boundary setting were defined.

The Peace of Westphalia ended the Eighty Years War between Spain and the Dutch Republic and the Thirty Years War in Europe. Relevant to understanding government today is that at the negotiations in the German city of Münster the principle of nonintervention was defined. Initially this concerned the ruler's right to determine the religion of her/his territory, but in the mid-eighteenth century this was extended to prescribe that rulers could not interfere in the domestic affairs of other countries (Krasner, 2001; S![]() renson, 2004, pp. 103–121). Indeed, governments generally do not intervene in each other's policies, and can do so only when a state's sovereignty is violated by another state (for instance, Iraq's invasion of Kuwait in 1991) or when a state commits serious crimes against humanity (for instance, genocide in Kosovo in 1995).

renson, 2004, pp. 103–121). Indeed, governments generally do not intervene in each other's policies, and can do so only when a state's sovereignty is violated by another state (for instance, Iraq's invasion of Kuwait in 1991) or when a state commits serious crimes against humanity (for instance, genocide in Kosovo in 1995).

Since the late nineteenth/early twentieth century international boundary setting has been organized as a stage-wise, linear process. The first step is that of delimitation. This is the legal process through which sovereign states determine and describe where their common boundary is located. It usually is the outcome of a process at the negotiation table. The second step is demarcation, which involves marking the position of boundaries on the ground. The final step is delineation, which is a comprehensive description of all the demarcation and mapping activities that document the boundary for future reference (see Al Sayel and others, 2009; Al Sayel, 2010, pp. 7–8).

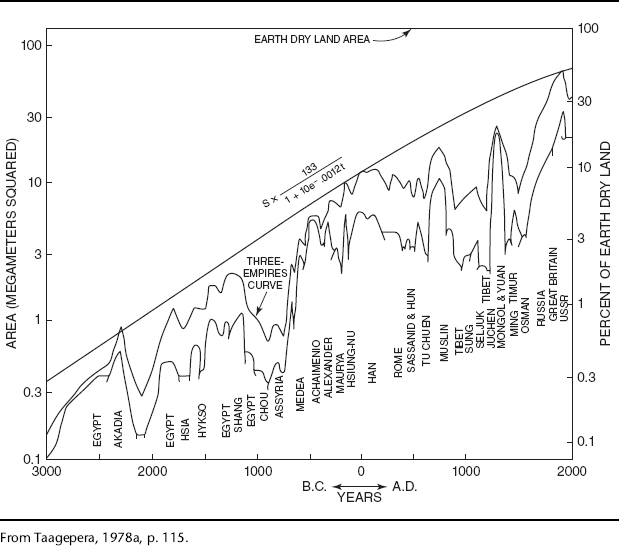

In the history of humankind it has only been during the past 50 years that the globe was mapped in its entirety. There is no unincorporated land left (save Antarctica). From the moment that sedentary communities emerged, which is now some 10,000 years ago, all world-systems, to use the concept of Christopher Chase-Dunn and Thomas Hall, underwent sequences of expansion and contraction, of centralization and decentralization. What started with a few pockets of sedentary habitation slowly but surely pulsated to finally encompass all land (Chase-Dunn and Hall, 1997, pp. 204–206). The long trend has been one of increasing polity size, and thus decreasing the number of autonomous polities. Rein Taagepera analyzed this trend with respect to the rise and fall of the world's empires (1978a, 1978b, 1979). The first phase from 2850 BCE to 700 BCE was prompted by beginning urbanization. The second phase until about 1600 CE was characterized by increasing capabilities to delegate power to territorially layered bureaucracies entrusted to help govern the territory on behalf of the ruler. The third phase came about as a consequence of the commercial-industrial revolution in Europe (1978a, pp. 121–123).

As the earth's lands were slowly but surely incorporated and the distinction between core (central city-state) and periphery (hinterland) disappeared, the territory within a polity was also more clearly delineated through hierarchically structured jurisdictions.

Taagepera's schema (see Figures 3.1 and 3.2) is appealing in its simplicity, but keep in mind that the historical record is far more complex, especially with regard to his second phase. Some empires were fairly successful in subjugating peripheral regions, such as the Chinese empire from the Han dynasty on. Other empires were much more loosely bound, and an example of that would be the Holy Roman Empire between the tenth and the early nineteenth centuries CE. Notwithstanding the differences, though, governments in both states and empires were slowly but surely increasing their hold on the territory through bureaucratization.

FIGURE 3.1. SIZE OF EMPIRES 3000 BCE-2000 CE

Subnational Jurisdictions: Historical Trends

The internal function of boundary setting serves to assure that the entire territory is effectively controlled from the center. Cities and city-states did not carve up their hinterland into jurisdictions, but as soon as the various urban centers interlocked and a larger territory was united under one ruler, the challenge was to find a way to maintain effective control. There have been two ways of doing so, and they appeared consecutively. At first a united polity would be governed through a system of itinerant, palace-based supervisory officials. They were often related to the monarch. Thus, in ancient Egypt, these officials traveled throughout the kingdom, and this situation existed until the sixth dynasty (2350–2150 BCE). At that time Egyptian society had become more populous, and the local/regional elites came to replace the itinerant officials. Egypt was then divided into 42 nomes or provinces each with a nomarch or governor. Hence, Egypt was the first state where subnational jurisdictions were established at the regional level (Finer, 1997, p. 151). Other united territories continued to be governed from the center through relatives of the ruler. To be sure, sometimes later empires would still administer the land through traveling officials. In fact, Charlemagne's court traveled the territory continuously, and he controlled his territory through personal representatives known as missi dominici.

City-states and empires were often engaged in warfare, seeking to expand the territory they controlled and extracted resources from. Conquered territories were indirectly ruled through local kings. It was Tiglath-Pileser III (745–728 BCE), king of the Assyrian empire, who introduced direct rule in all conquered lands. Indeed, the Assyrians were the first to introduce regional or provincial government in the conquered territories, effectively treating them as part of the heartland of the empire (Finer, 1997, pp. 224–225). There were local officials as well: district governors for the supervision of several towns and villages, and headmen in each of the localities.

The next step in the territorialization of the globe happened during the reign of Emperor Diocletian (284–305 CE) (see, for instance, Abbott and Johnson, 1968). In 286 he subdivided the entire Roman Empire in four prefectures, 12 dioceses, and 101 provinces. These provinces, in turn, were divided into civitates, and the latter in several pagi. Thus, the Diocletian reforms for the first time in history established a layered territorial hierarchy from the smallest local level up to the upper-regional levels. This has been very important to the territorialization of the globe, since with the decline of the Roman Empire, the Catholic Church adopted the Roman territorial organization as its own. The pagi became parishes; the civitates became the seat of bishoprics, and the Roman provinces became church provinces (i.e., archbishopric). Indeed, the church not only copied the territorial structure but also took over a variety of services (Miller, 1983, pp. 278–279).

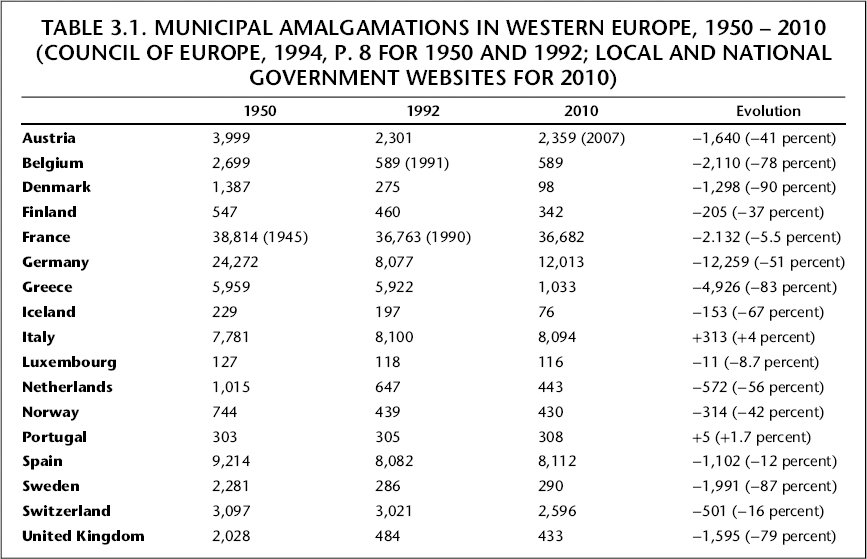

This is important for two reasons. First, a system of layered subnational jurisdictions can be found all over the contemporary world, and in many cases was actually introduced by colonizing powers. The second reason is that there are marked differences between countries when it comes to which level of subnational government is considered the most important: the local or the regional level? In the territories occupied by Rome and of which the secular jurisdictions became the Catholic Church's religious jurisdictions, it seems that at least until the 1980s the regional level of government was more important than the local level. In territories where local tribal life was not obliterated by Roman occupation, a tradition of local self-government continued to exist. These territories often turned to Protestantism, and the organization of the various Protestant denominations mirrored much more the local, self-sufficient, self-governing organizational structure of early Christianity. Furthermore, many Protestant territories no longer accepted the supranational, centralizing supervision of the Catholic Church (Rokkan and Urwin, 1983, p. 33). This theory can be tested by looking at, for instance, municipal amalgamations (see Table 3.1).

They started shortly after the Second World War, in the Protestant countries, motivated by the desire to enhance and improve local public service delivery. It helped that these countries had a tradition of or were amenable to local self-government (Page, 1991, pp. 139–140). In Table 3.1 we can see how the number of municipalities declined strongly in Protestant-dominated countries such as Denmark, Sweden, the United Kingdom, the Netherlands, and Germany. The decline would have been larger in Germany had it not been for the reunification in 1991, which added municipalities. Municipal amalgamations were much less extensive in the Catholic countries. In France and Spain the number of local governments only declined a little; in Portugal and Italy the number of municipalities actually increased somewhat. The hypothesis that in territories not occupied by Rome (and thus with more of a tradition of local self-government, or at least of less disturbed tribal government) municipal amalgamations started earlier and were more extensive than those in Catholic countries can also be tested by looking at variation within one country. For instance, in Germany the Länder of Baden-Württemberg, Bavaria, and Rhineland-Palatinate are predominantly Catholic and amalgamations of local government have so far been more limited than in the Protestant north (Hesse, 1991, pp. 365–368). Another example is provided by the Catholic provinces of Limburg and Brabant in the south of the Netherlands. While local government amalgamations started shortly after the Second World War, they were mainly limited to the Protestant north and mostly occurred upon local initiative. In the two southern provinces amalgamations were imposed by Parliament and mainly not until the late 1980s. To have a Roman and Catholic past is not only relevant to Western Europe. European settlers in New England adopted a commonwealth tradition of local self-government based on a charter or constitution. The southern United States was settled by Spain and France, both countries with much more centralized as well as elite government (Elazar, 1966, pp. 186–188). In fact, and more in general, colonizing countries organized subnational government after the fashion of their own country (see later).

Subnational Jurisdictions: The Contemporary Situation

Modern states increasingly turned to territorial strategies to control what people can do inside national boundaries. With regard to territoriality, many authors focus on the external element of territory (for instance, sovereignty, international borders, and political identity) and have less attention for the spatial organization of state administration within a territory. One exception to this tendency is Michael Mann, who writes that societies “are constituted of multiple overlapping and intersecting sociospatial networks of power.” (1986a, p. 1) One of those networks is political power (next to ideological, economic, and military), which in the modern state is structured and visible in centralized, territorial regulation (1986a, p. 10–11).

All modern states have divided their territories into complex and layered or nested political jurisdictions for, among others, taxing and zoning purposes. As became clear in the previous section, this is not a feature of modern states only. Most contemporary states have anywhere between two and five tiers of government. The national government represents one tier in a system of multilevel government that ranges from the supranational level (the United Nations, the European Union, the military and the economic alliances, etc.) to the most local level.

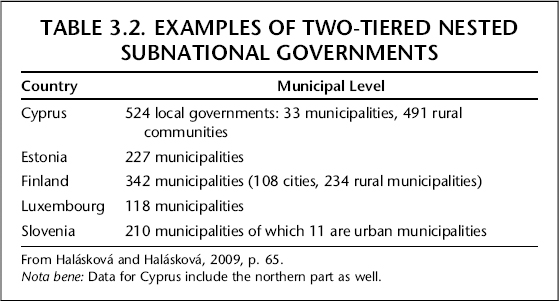

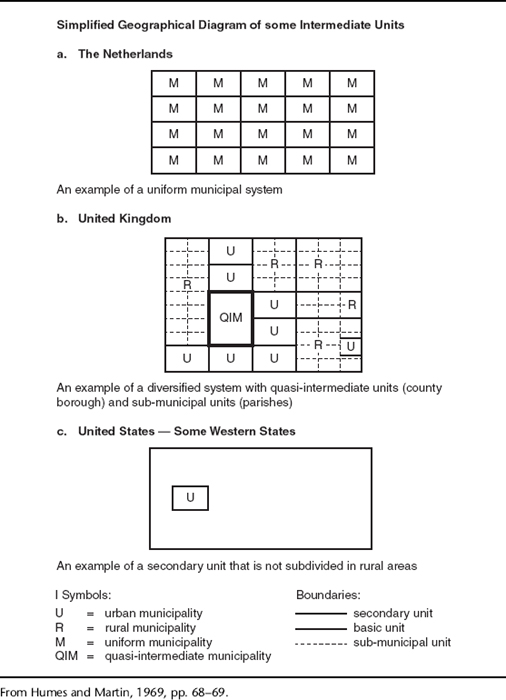

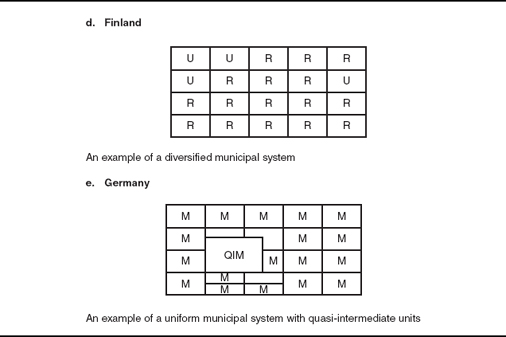

Table 3.2 requires some explanation. First, it is clear that some countries still have a distinction between urban and rural local governments. Often the number of tiers in rural areas exceeds that in urban areas. This is in part because the former have smaller populations and fewer financial resources so that rural communities seek intermunicipal arrangements to provide for services (see also later). The distinction between urban and rural communities dates back to the Middle Ages when the rural communities developed out of the parishes of the Catholic Church and when some cities acquired charters that provided them with some degree of autonomy from an overlord. Since the Napoleonic reforms of the early nineteenth century, the distinction between urban and rural local governments has become less and less common and has been replaced with uniform pattern of local government as can be found in, for instance, the Netherlands or Luxembourg. Finland, though, still has urban and rural municipalities (see Figure 3.2).

Second, there is sometimes a regional level of government that some scholars regard as a third tier (see, for instance, Hooghe and Marks, 2009, p. 229 with regard to Luxembourg) but cannot really be counted as a third tier. Thus, in Finland there are 90 jurisdictional districts and another 20 regional councils, but both these operate as regional “arms” of the national state and are thus an example of deconcentration. The same is the case in Luxembourg where each of the 116 municipalities belongs to one of 12 cantons, and to one of three districts.

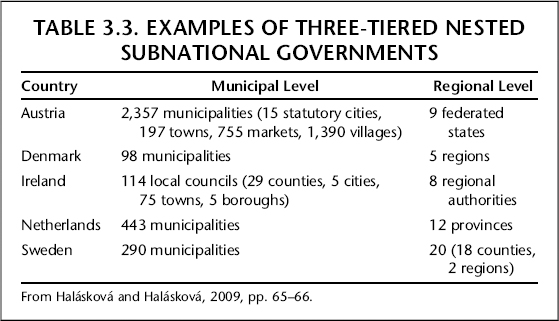

In Table 3.3 the Netherlands is a country with uniform local and provincial governments. The regional level is not an administrative extension of national government. It has its own responsibilities and policies. Austria is a country with four types of local government but is uniform in territorial structure at the regional level.

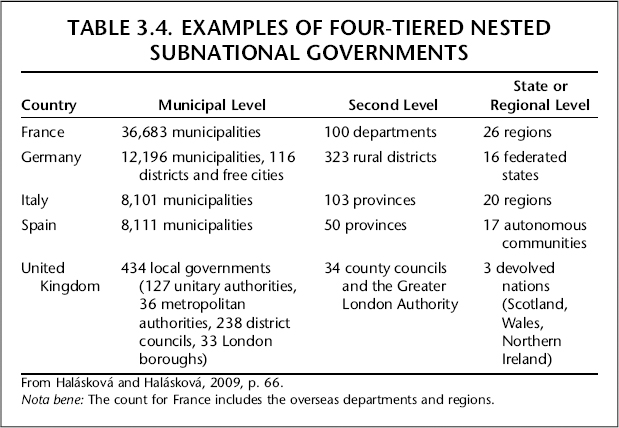

In Table 3.4 France has a system of uniform government at all levels, but the United Kingdom has four different types of local authorities. France is also one of those countries with a large number of small to very small municipalities. From that we can infer that service delivery and public policy at the departmental and regional levels are far more important than at the local level. Rural municipalities may be large in territorial size but small in population, while urban municipalities may be small or large in terms of territory but certainly large in terms of population. Rural municipalities do not have the tax base to provide a range of services, but do have a sense of tangible community. Urban municipalities can offer a wide range of services, but the sense of community may be much less. In Figure 3.2 some examples are provided of local government structures in a few, mainly, European countries.

FIGURE 3.2. SIMPLIFIED DIAGRAMS OF LOCAL GOVERNMENT UNITS

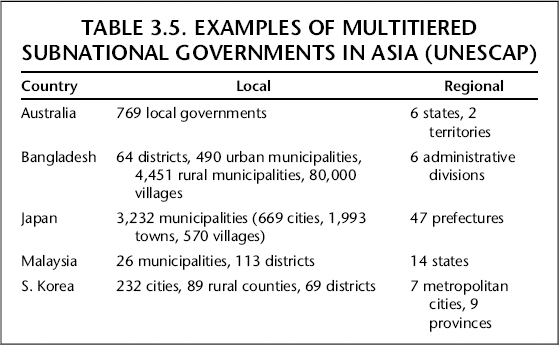

This system of multitiered government can be found all over the world. In Latin American countries the number of municipalities has grown in the past 20 years as a function of urbanization and of rural fragmentation (Nickson, 2011, p. 17). In many countries there are still urban and rural municipalities (Nickson, 2011, p. 8). Having been colonized by the Portuguese and the Spaniards, local government was embedded in a highly centralized system until recently; in the past 20 years many countries have adopted decentralization policies (Nickson, 2011, p. 4). The territorial structure of the Francophone countries in Africa is usually quite centralized, and with more emphasis on deconcentration (which involves transfer of tasks only) than on decentralization (which involves transfer of tasks and of decision-making authority). In Anglophone countries there is more variation in decentralization with strong federalist systems as well as with highly centralized unitary states (United States Agency for International Development, USAID, 2010, p. 49). Just as elsewhere we find federal and unitary systems of government in Asia and the Pacific. Most countries have three-tiered systems. Some countries have several types of regional and local government. Thus, at the regional level China has 22 provinces, five autonomous regions, two special administration regions, and four municipalities that fall directly under the authority of national government. At the local level there are county-level cities, cities, townships, autonomous prefectures, and autonomous counties. Many Asian and Pacific countries distinguish rural (towns) from urban (cities) municipalities (United Nations Economic and Social Committee for Asia and the Pacific, UNESCAP, no year; see Table 3.5).

Previously we described processes of amalgamation in Europe, but amalgamations have occurred elsewhere as well. For instance, in Australia a variety of local communities were consolidated in the past 20 years without much community consultation. As a consequence, some are now considering the possibility of de-amalgamation (Dollery and others, 2011). Amalgamations are often accompanied by decentralization, and are generally successful when local government jurisdictions are reflective of some degree of community: social, cultural, ethnic, and so forth. They have been far less successful in Africa where formal local jurisdictions were superimposed above, and still coexist with, traditional tribal authorities. The official jurisdictions are often too large, do not correspond with local communities of varying size, and suffer from lacking ties between the elected political leadership and the population (Wunsch, 2008, pp. 33–34).

A complex subnational government structure can be found in the United States. At the state, i.e., regional level, government is uniformly structured (50 states); at the local level, however, there is intriguing variation. The total number of subnational units has significantly decreased in the past 70 years: from 155,116 units in 1942 to 87,576 in 2002 (United States Census Bureau, 2002). These numbers include all subnational jurisdictions. The number of states has increased with the addition of Alaska and Hawaii after the Second World War. The number of county governments has been quite stable from 3,043 in 1952 to 3,034 in 2002. Then at the local level there are two types of government. General-purpose governments (cities, townships) offer a wide range of services. There were 34,009 general-purpose governments in 1952; 60 years later this had increased to 35,933. The increase is solely in municipal governments, an indication of continued suburbanization (Hardy, no year). The number of towns or township governments actually declined in the same period from 17,202 to 16,504. The main drop in jurisdictions at the local level has been caused by an overall decline in special-purpose local governments.

There are two types of special-purpose local governments in the United States. The largest single group is that of the school districts, and of the 67,335 in 1952 there are only 13,506 left in 2002. A comparable amalgamation of school districts has taken place in Canada. In the United States all other special-purpose governments actually increased in numbers from 12,340 in 1952 to 35,052 in 2002. Initially, special districts were established some two centuries ago for the provision of special services at the regional level and included boards of poverty relief, of police, of ports, of sewer/water, of health, and of sanitation (this paragraph based on Martin and Bradshaw, no year, pp. 2–4). A second wave was prompted by fragmentation of the population, macroeconomic boom-bust cycles, and home rule movements between 1870 and 1920. People demanded urban services outside the traditional municipal boundary, desiring region-wide services connecting the city with the growing suburbs. A third wave happened during the 1930s and 1940s in the effort to curb power from big city administrators. Rapid suburbanization after the Second World War provided further incentives for special districts.

More than 90 percent of special districts are single-purpose governments that perform a function independent from general-purpose government; that have the power to make financial decisions and levy taxes; and are administered by a popularly elected board. How great the variation in special-district governments can be gauged from a simple listing (see U.S. Census Bureau: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Special-purpose_district). These special-purpose governments determine their own boundaries, and thus the various jurisdictions at the local level come across as a patchwork, testimony to the extent to which the United States' local governments are polycentric. Special-purpose governments are not unique to the United States. Switzerland is another country with a large number of special-purpose governments. In countries where the population of general-purpose jurisdictions is small, local governments seek to provide services on the basis of an intermunicipal agreement. There are also intramunicipal special-purpose authorities, and these can be found mainly in Australia, Canada, India, New Zealand, and the United States. The best examples of these are school districts, established to protect education from politically inspired influence (Humes and Martin, 1969, pp. 73–76).

Of all territorially defined jurisdictions, the local government level is the one that people can most easily identify with. It is, in the words of Mill, the “school of democracy.” (1984, p. 378) But not only that, it is also the level where the largest range of public services is provided; it is at that level that citizens can actually see what governments can do for them. People often think of “big government” as concerning the national level, but they do not consider the local level. In the European Union with 27 member states there are 91,252 municipal governments and only 935 intermediary and 319 federated subnational governments (Hermenier, 2009, p. 4). In the United States as well, the local level represents by far the largest number of jurisdictions. How much variation there is across the globe would require research, and in some countries the local level may be large in terms of number of municipalities (for instance, France) but low in terms of personnel size (more on that in Chapter 8). With the exception of Africa, one of the main trends in the past 20 to 40 years has been that of strengthening local governments, first through amalgamations and next by means of decentralization (for Europe, see Wollmann, 2009, pp. 89–90).

Bureaucracy as Organizational Structure: The Bureaucratization of the World

The potential of governing a large territory can only be realized fully with the help of sophisticated coordinating mechanisms (Merelman, 1988, pp. 587, 595, and 598). Territorialization does not visibly improve the territory and the communities living in it. Territory and people need to be monitored, and that takes people (military, police, etc.) who are not productive otherwise and who need to be supported through taxes. It is in this sense that bureaucracy and bureaucrats can be a burden to society. Some anthropologists argued that complex social organization, which includes bureaucracy, coordinates people and resources and thus solves rather than creates problems. Complex organizations help establish social stability (for instance, Cohen, 1985). Others argued the opposite case (for instance, Paynter, 1989). A case can, indeed, be made that bureaucratic organization was rather parasitic for most of history, serving those in power rather than the people. But can we still say that bureaucracy is a problem rather than a solution? Can the modern state do without bureaucracy? Can political officeholders work without the specialist's and generalist's input of the career civil servant? We argue that bureaucracies contribute to the collapse of society when their cost to society is larger than their benefit. Hence, when bureaucracies exist only to extract resources in kind, labor, and/or money from the population at large, then they are parasitic. However, when bureaucracies actually provide services to populations, and when the benefits of their existence outweigh the costs, bureaucracies will continue to exist. We believe that in the modern world the latter situation has become common, at least in democratically governed systems: Bureaucracies are in general no longer a burden (Masters, 1986, p. 157).

The work of state functionaries has to be coordinated. Throughout history this has been done through organization, and bureaucracy is the best-known type of organization in the contemporary world. It has been argued that rudiments of bureaucratization existed at least 12,000 to 19,000 years ago, given that at least one archaeological site provides some indication of such organizational features as division of labor, hierarchy, and rules regulating operations and behavior (Nystrom and Nystrom, 1998). However, that seems to be stretching the concept of bureaucracy. These three aspects of organization are not unique to bureaucracy. Common pool resource management systems, as analyzed by E. Ostrom and many associates across the globe, are not described as if they are bureaucracies, and yet they do exhibit specialization and have hierarchy and rules-in-use.

Bureaucratization is a process that many defined as one where organizations strengthen and expand the features Weber listed as characteristic for bureaucracy. His definition contains at least two elements: bureaucracy as type of organization (Chapter 6) and bureaucracy as personnel system (Chapter 8). In this chapter we will limit ourselves to bureaucracy as it unfolded over time.

As a type of organization characterized by high degrees of standardization then, clearly, bureaucracies existed in antiquity. Irrigation, food storage (granaries), recording economic transactions, and taxation are all activities that required a bureaucracy with specialized agencies employing people trained in keeping records. There is evidence of organizing public activities in separate departments in most ancient civilizations that had become states (for instance, Chadwick, 1959). Departmentalization went hand-in-hand with some degree of professionalization; that is, those who kept records had to be literate. This may seem obvious, but in societies where the large majority of people could not read or write, it is a great accomplishment to master the skill of literacy. Civilizations and states may have waxed and waned but, once established, bureaucracy would not wax and wane. Naturally, specific agencies and government bureaus disappeared with the demise of a polity, but as an organizational device, bureaucracy has been around for millennia. Downs is correct to observe that very few bureaus managed to survive long periods of time (1967, p. 23), but he refers to specific examples of bureaus, not to the phenomenon of bureaus.

This is not the place to provide a detailed description of the emergence and development of government departments (see Raadschelders, 1998b, pp. 114–125), but departmentalization occurred everywhere once societies became more complex. Departmentalization concerns the bureaucratization of the organization and thus of the functions and activities of government. Structuring territory and organization has often preceded the professionalization of personnel. That is, for most of history those who could be designated as public sector personnel generally worked for a ruler, not for the people. Rulers appointed public sector personnel on the basis of ascription and/or relationship first; merit (literacy, relevant experience) came second. Once public-sector personnel becomes a civil service, i.e., a body of functionaries serving the people on the basis of individual expertise and experience, modern bureaucracy arises. This happened everywhere, in England (Aylmer, 1980) as well as in the Ashanti Empire (Wilks, 1966), just to mention two examples, and did so from the second half of the eighteenth century.

So far we discussed the emergence and development of bureaucracy as organization, but at least one author argued that society itself has bureaucratized as well (the following based on Jacoby, 1976). To Jacoby bureaucratization represents the situation where people's lives and behaviors are increasingly controlled by government agencies: “not only is he unable to escape from the regulation and manipulation, he seems to depend on it.” (p. 1). People both complain about but also demand bureaucracy: “Modern man has lost spontaneous self-help. Projects which help others have become rarer; people now depend on specialized agencies to which they can turn.” (Jacoby, 1976, p. 1) This observation is immediately followed by a crucial comment:

Centralization of all functions and accumulation of power are on the inside (JR/EVG: government); isolation and impotence of the individual are on the outside (JR/EVG: society). These opposites have consistently intensified each other. Thus the looser western interpersonal relations became, the more they depended on bureaucracy (1–2; emphasis added).

This comment concerns one of the most major societal changes in the history of humanity, i.e., how the “triple whammy” (see Chapter 2) of industrialization, urbanization, and population growth “moved” humanity from a society based on (inter)personal relations to a society of imagined communities. In the industrial society, it is no longer the small, physical community of old that protects us from the hazards of life, but it is government. And how does government protect its people? It does so by offering services hitherto provided between individuals in physical communities of people. The virtue of caring for one another when in need is normal and expected in physical communities. Once isolated from one another, as is the case in the urbanized world, it is government that cares for those who cannot care for themselves. In a way, the welfare state is nothing but an institutional arrangement substituting for the type of community care that existed locally throughout history. Henry Jacoby was not the first to see where society was headed. Already in the 1830s De Tocqueville observed that “Democracy loosens social ties, but tightens natural ones: it brings kindred more closely together, whilst it throws citizens more apart . . .” (2000, p. 233) Large-scale democracy emerges across the globe wherever societies become urban, and it is urbanization and industrialization that loosen social ties, that take people out of the natural community and back into the nuclear family. To what extent is this the case today? Have people truly become dependent upon government? Have social ties loosened, and if so, to what extent? An answer cannot be given, since it is impossible to measure “loosening of social ties” in a way that will satisfy everyone. But, considering that there are thousands upon thousands of common-pool resource management systems across the globe, there is reason to believe that bureaucratization and democratization have not overtaken social coordination mechanisms entirely.

Max Weber's Die Bürokratisierung gehört die Zukunft (1980, p. 834), echoed in Joseph Schumpeter's “Its expansion is the one certain thing about our future” (1950, p. 294), is both true and untrue. What is true is that bureaucracies have grown in size, all over the world, by any measure we have: personnel size, revenue and expenditure, organizational differentiation, and regulatory activity. At the same time, bureaucracy has not gobbled up democracy as Weber feared, and this can be demonstrated in at least three ways. First, the civil service generally supports those who are elected in political office. Second, next to the common-pool resource systems, there are plenty of other examples of self-governance (e.g., homeowners organizations, sports clubs, churches, and so on). Third, and finally, an administrative state where the civil service dominates all politics has not become reality.

The Influence of Colonization

In the year 1900 about 35 percent of land surface of the earth was colonized (Pounds, 1990, p. 349). Colonization has been of enormous influence upon the structuring of governments throughout the globe. Looking at the state-system from an international relations point of view, Chase-Dunn and others argued that the colonial empires of a few European states “brought the whole earth into a single relatively homogenous global polity for the first time.” (2009, p. 275) The European interstate system established at the Conference of Westphalia in 1648 is still in place, and today it encompasses the globe. A second aspect of globalization from the international relations point of view is that we now have a layer of international organizations in the various world regions (Chase-Dunn and others, 2009, p. 276). Some of them are truly global such as the United Nations, the International Monetary Fund, and the World Bank. Others span world regions. However, it is not just the international state system that has become global. Global is also how governments are structured. Territorialization, as evidenced by the establishment of nested jurisdictions, and bureaucratization as visible in the creation of specialized agencies or departments, can be found from small island states to the largest polities in the world.

That nested territorialization and hierarchies have become the dominant mode of structuring government may be a fact of social life in many species, but in its dissemination across the globe it is also a function of colonization. There are two types of colonization (Tully, 2000). The type we are most familiar with is known as external colonization, which is when an imperial power takes and governs territories outside its own sovereignty. This has happened mainly in Latin America, Africa, and Asia. Less familiar is internal colonization, where the initial inhabitants of a territory are confronted with efforts at domination by a national or neighboring power, and is what happened in North America, Australia, and New Zealand. With regard to external colonization, a few Western European countries engaged in this from the early fifteenth century on.

The first imperial age (1419–1760) started with a Mediterranean phase dominated by Spain and Portugal. They established trade factories under state rule and subdivided the territory in administrative districts. Spain established four vice-royalties in Latin America. New Spain (present-day Mexico) and Peru were created in the sixteenth century; New Granada (present-day Colombia, Ecuador, and Venezuela) followed in 1739 and Rio de la Plata (encompassing Argentina, Bolivia, Paraguay, and Uruguay) in 1776. The Atlantic phase (1550–1760) was dominated by the Dutch Republic, England, and France. The Dutch and English used autonomous companies to rule in name of the mother country (for instance, East and West India Companies). Generally, Belgian, French, Japanese, Portuguese, and Spanish colonizers favored some degree of direct, more centralized rule, while American, Dutch, and English colonizers were partial to indirect, more decentralized rule (Geering and others, 2011, p. 401). In the latter case, existing local institutional arrangements and their officeholders were employed by the mother country to help govern the territory. Thus, the British used the existing Muslim governing institutions in northern Nigeria. Direct rule was more common where institutional systems of rule did not exceed the band level, such as in North America and Australia. The British also used direct rule in Burma, since they had abolished the indigenous political systems.

The first wave of decolonization occurred in 1770–1820 with the independence of the United States of America and of many Central and South American countries. The latter was made possible because the Napoleonic wars and occupations meant that mother countries could no longer effectively control the colonies. The second imperial age involved the occupation of large parts of Africa by England, France, Germany, Italy, and Belgium. Especially tragic has been the presence of colonial empires in Africa, where local, tribal boundaries were simply cut by new territorial boundaries (see Davidson, 1992). The second wave of decolonization occurred after the Second World War. The Middle East and Asia were first with Jordan, Lebanon, and Syria in 1946 and Israel in 1948; Burma (nowadays Myanmar) in 1948; India in 1947; Indonesia in 1949; Pakistan (and Bangladesh) in 1947; the Philippines in 1946; and Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia in 1954. Africa followed with the Sudan and Morocco in 1956, Ghana in 1957, and a series of decolonizations in Africa between 1960 and 1965. The last of the larger territories to become independent in that continent were Angola (1975), Mozambique (1975), and Namibia (1990). More recently some smaller territories have become independent, such as East Timor in 1999.

A major consequence of colonization has been that various Western traditions regarding the structure and functioning of government were imposed on the colonies. We already mentioned the creation of artificial boundaries negotiated between the colonizers. After independence, all former colonies simply maintained the territorial structures established by the colonizers. However, colonization was not necessary for the adoption of Western styles of governing. Thailand, the only country in Southeast Asia that escaped being colonized, followed trends in colonized states in the region by adopting internal administrative reforms such as a Western style land code and claiming ownership of all “unoccupied” land at the end of the nineteenth century. Local administration was territorialized and centralized throughout the country, and layers of nobles and local lords were transformed into salaried officials, as had happened in Europe during and after the Napoleonic reforms. Provinces were divided into districts, and a member of the local nobility was simply transformed into a district officer. Below that level, direct masters of serfs were replaced with village heads and subdistrict chiefs. The office of village head was similar to that of the British system in India and the Dutch system in Netherlands East Indies. The highly centralized provincial and district administration had more resemblance to the French colonies in Indochina (Vandergeest and Peluso, 1995, pp. 396, 398, 399, and 401).

Western influence in former colonies has not diminished. Indeed, bilateral and multilateral donors of development have since the 1980s demanded Western-style reforms including anticorruption measures through civil service reform and accountability reforms (concerning the budgetary process, information technology and record management, and audit systems), decentralization (see earlier), privatization and marketization, strengthening service delivery through private and nongovernmental organizations, and the establishment of civic associations. Thus, Western political beliefs in freedom, self-determination, democracy, and market are advanced in non-Western countries. Some say that these reforms are pursued to a point where they actually reinforce Western beliefs rather than support indigenous traditions of governing (Farazmand, 1999).

Concluding Remarks: Boundaries Creating Polities

To understand the challenges that contemporary governments face everywhere in the world, it is necessary to understand that they all more or less operate upon the same structural properties. It is, indeed, striking to see how territorialization through jurisdictions and horizontal and vertical differentiation of organization through bureaucracy have become pretty much universal (Hooghe and Marks, 2009, p. 238). With regard to territorialization, consider it as a process whereby slowly but surely the reach of sedentary pockets at the local level expanded to incorporate ever more land. Initially, the dominant polity level is that of the city-state, and the Mesopotamian city-state system is the earliest example of this. At some point polities expanded to be defined at a regional and then a state level that can only be administered when the territory is subdivided into smaller jurisdictions, which is what happened first in ancient Egypt. The next step was that of conquering polities that organized their newly acquired lands in a manner comparable to that of their own. The Assyrian and the Roman Empires are the earliest examples ofthat. The same was later done through colonization of parts of Africa, Asia, and Latin America.

For much of history polity size oscillated between city-state and empire, but from the seventeenth century on, the state became the most dominant type of polity. It was decolonization through which the political-administrative traditions of a few European states disseminated throughout the globe (Chase-Dunn and others, 2009, pp. 273–275). This spread of territorial and bureaucratic organization meant that, at some point, states “bumped” into one another. In terms of external relations they had to establish rationales for their boundaries. Internally, states had to find a balance with subnational governments and develop a sense of nationhood and citizenship. This process of state making, of nation building, and of civic awareness will be the topic of the next chapter.