Chapter 11

The Bronze Age and the Invention of Writing

Introduction: Theatre Becomes Drama

In 1985, I received a phone call from director Robert Cohen (author of the best-selling text, Acting One, among many others), asking me if I would like to compose a sound score for his production of King Lear at the Colorado Shakespeare Festival the following summer. Even in 1985 Robert had established a name for himself, so when one of the more prominent directors and authors in the American Theatre called, I gladly accepted, knowing that it was an invitation I did not want to screw up. I did what I often did with directors: I asked him what sorts of things he was reading to prepare for directing the play. Robert turned me on to a book, Marvin Rosenberg’s The Masks of King Lear, one of a series of books Rosenberg wrote that traced the production history of Shakespeare’s plays. The Masks of King Lear provided an extraordinary production history of King Lear from Shakespeare’s original staging to modern times. Intricately woven into this history were detailed descriptions of all the diverse ways that Lear had been played over the centuries, from Edwin Booth to John Gielgud, and many more. It had never occurred to me before that in Shakespeare’s play there could be many Lears.

I had always assumed that actors who took on the role sought to uncover Shakespeare’s Lear. I was never so naïve as to think that there was only one way to play the extraordinary complexity of a character like Lear, but nevertheless labored under the belief that an actor sought to bring to life the character that Shakespeare first created. The book clued me in to something completely different: the seemingly endless possibilities the text suggested. But why? Why did the written text, passed down through many generations, fail so miserably in telling subsequent actors precisely how the role was to be played? One inevitable conclusion to which I arrived, was that the text failed to communicate the music of the character. Somehow, in the storing and recalling of the performance, the musical performance of the actors had gotten lost. But without printed music carrying the written ideas of the character’s journey, the script left open a wide range of interpretations of the character of Lear. For the first time, it became clear to me how critical my score would be in bringing to life the emotional journey of the characters in the play.

I think most everyone would agree that the loss of this music in the printed word turned out to be a tremendous advantage for theatre. It freed every theatre company, every production team, every actor to create their own music to bring new life to the ideas in the script, each appropriate to the era. Such freedom to create that music allows the play to resonate in the present moment, allows us not just to consider the ideas of the play, but to live in the story and to emotionally experience the journey of the play in the present. Imagine if the only production of King Lear we could ever consider doing was the performance by the King’s Men at Whitehall Palace on December 26, 1606 (Shakespeare Quartos Archive n.d.)! Film provides a clear record of the music of every production. In doing so, it tends to remove the ambiguity that allows the endless interpretations of the script that theatre allows. The ambiguity of the music in written play scripts allows endlessly new interpretations, such as the paper project of King Lear I developed with a group of students for the 2003 Scenofest at the Prague Quadrennial. In this production, King Lear was portrayed by a very troubled “Uncle Sam” wandering among the ruins of the World Trade Center in the years immediately following 9/11 (Thomas et al. 2002–2003).

Finding new music to carry ancient ideas keeps plays endlessly relevant for modern audiences. And yet, for all the advantages and advancements of civilization made possible by the advent of written language, we must stop and consider that something got lost along the way when idea first became separated from music in theatre, when theatre became drama, the written record of theatre. Anyone who has ever written an email that got misinterpreted because the reader imagined a music distinctly different from the music the author intended surely understands the potentially devastating consequences of such a separation. In many media, perhaps starting with opera, but certainly continuing through film, video, and even modern audio/video messaging applications such as FaceTime, music has been fundamentally reconnected with idea, leaving much less doubt about the author’s intentions. Plays and scripts provide much less specific indications. We must create the experience anew with each production, and my fundamental thesis in this book continues to be that we want to create in an environment in which music and idea come together in mimesis organically rather than one reacting to the other retroactively. Such an organic process occurs quite naturally for the actors, but not necessarily for the composer or sound designer. It is a process that is not always practical, but almost always highly desirable, and that’s why many composers and sound designers have taken to sitting in rehearsals from the first reading through the opening. Fortunately, the tools we use to create sound scores have also advanced significantly to allow this to happen.

Figure 11.1 King Lear @ Ground Zero at the 2003 Prague Quadrennial.

Credit: Directed by Richard K. Thomas. Project members included Matthew Gowin, Kristy Lee McManus, Timothy J. Rogers, Justin Seward, Stephanie Shaw, David Swenson, and Jesse Dreikosen.

With that in mind, this chapter will explore how music and idea first became separated in the period immediately following the Neolithic or new stone age, a period that witnessed the tremendous explosion of invention and advancement in social order called the Bronze Age. The Bronze Age lasted very roughly from about 3000 bce to 1000 bce. The exact dates vary depending on the part of the world in which progress took place. We’ll explore the development of musical instruments during this period, and their close connection to spirituality throughout the world. Then we’ll consider the advent of writing itself. We’ll explore how music finally separated from idea in our recorded history, even though both remained indivisible in the performance art of this age and the ages that would follow and led to the development of the first fully autonomous theatres.

The Bronze Age

Humans developed the ability to work with metals starting somewhere in the fourth to fifth millennium bce. One of the first metals most humans made malleable was bronze, so the period is referred to as the Bronze Age. Actually, the first metal most humans made malleable was copper, about 7000 bce in sites such as the Vinča culture site in eastern Serbia (Radivojević et al. 2010, 2775).

Later discoveries found that adding tin to copper produced a harder and more durable metal, bronze, and this became the predominant metal making technique for millennia. That’s why the period is called the Bronze Age.

The early temples and villages of the Neolithic turned into cities, and the first four great civilizations arose during this period, all based around rivers.

Mesopotamia, which literally means “the land between rivers” arose in the land we now refer to as Syria and Iraq. Relatively nearby and closely connected was Egypt, a great civilization that arose around the Nile River. These two civilizations created the world’s first “trans-regional civilization” that spanned from Anatolia (modern Turkey) in the northwest, to Central Asia (Turkmenistan and Afghanistan) in the northeast, to Arabia (Saudi Arabia) in the southeast, to the Sudan in Africa in the southwest (Wright 1989, 47). The third great civilization arose along the alluvial1 plain of the Indus River and its tributaries in India and Pakistan. It stretched from Kashmir in the north to the Himalayas in the east, to Afghanistan to the west and the Indian Ocean to the south (Wright 1989, 96). The fourth great civilization arose along the Yellow River and its tributaries in China, where the first great Chinese dynasty, the Shang, arose, although some argue for an earlier dynasty, the Xia, based around a different ethnic group2 (Liu and Xu 2007, 886).

It certainly can be argued that neither the ability to make bronze, nor the development of the first great civilizations, could have taken place without the aid of sophisticated means of communication. Human ability to manipulate language exploded during this period.

Figure 11.2 Map of Vinča culture in parts of Serbia, Croatia, Bosnia, and Romania.

Credit: Best-Backgrounds/Shutterstock.com. Adapted by Richard K. Thomas. Data from Vitezovic, S. 2017. “Antler Exploitation and Management in the Vinča Culture: An Overview of Evidence from Serbia.” Quaternary International. Accessed July 21, 2017. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.quaint.2016.12.048.

Figure 11.4 Map of the first four great civilizations of the world.

Credit: Best-Backgrounds/Shutterstock.com. Adapted by Richard K. Thomas.

Curiously, these languages all formed during the period of the biblical story of the tower of Babel, described in Genesis chapter 11.

Mallory and Adams argue that there were three specific biblical accounts widely accepted throughout history that governed the origin of language (2006, 4). The first was a single language—Hebrew—spoken by Adam and Eve, from which all other languages would derive. The second biblical account, found in Genesis chapters 6–10, produces three languages spoken by the offspring of Noah’s sons after the flood. The first included the descendants of Shem, mainly Arabic and Jewish people who spoke the Semitic language. The second were the descendants of Ham, the Hamites, who populated northern Africa, including the Egyptians. Finally, there was the offspring of Japheth, Gentiles who would eventually populate Europe. The final biblical linguistic event that describes the spread of languages around the world is the story of Babel. Babel is another name for Babylon, the civilization that arose in Mesopotamia around the twenty-fourth century bce (Joshua 2011). The group that settled in Mesopotamia decided to build a tower to the heavens. The Lord came down from the heavens and said “not so fast,” and “confounded” their language into many other languages while scattering them across the face of the earth.

The story of Babel is reflected in evidence that one common language, called the Proto-Indo-European, or PIE language suddenly (or at least suddenly as evolution goes) split into several hundred languages (Donald 1993, 158). Mallory and Adams describe the PIE language as “the world’s largest language family” (2006, xxii), one that produced the languages that are today widely spoken in the Americas, Europe, and western and southern Asia (Violatti 2014). Of course, none of the archaeological evidence points to the single Indo-European language originating in Babylon. The particular Semitic branch of languages spoken in Mesopotamia and Babylon has largely died away (Encyclopaedia Britannica 2011). Two prominent theories place the origins of the PIE language either in Anatolia (Turkey) about 7000 bce, or in the more temperate climates of the Ukraine and southern Russia around 4000 bce (2006, 460–461).

The PIE languages are, of course, not the only languages that spread quickly around the world. Many “proto-languages” developed nearly simultaneously during the Bronze Age. The rapid development of language most certainly significantly impacted the equally rapid spread of civilization around the globe. I mention the PIE family of languages specifically because it will be of interest in the next chapter.

Figure 11.6 One proposed PIE migration, the Kurgan hypothesis.

Credit: Best-Backgrounds/Shutterstock.com. Adapted by Richard K. Thomas. Map based on data from Anthony, David W. 2007. The Horse, the Wheel, and Language: How Bronze-Age Riders from the Eurasian Steppes Shaped the Modern World. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 87.

By the third and second millennium bce, musical instruments had also developed tremendously from the rattles, bone flutes, and primitive drums of earlier periods. Musicologist Curt Sachs identified two classes of musical instruments found in Paleolithic excavations and geographically scattered all over the world: idiophones (percussion instruments without a membrane) and aerophones (wind instruments).

The Neolithic period brought two additional classes of instruments, membranophones (percussion instruments with membranes) and chordophones (stringed instruments such as the lyre) (Sachs 1940, 63).

By the Bronze Age, a wealth and wide variety of instruments in these four categories all appear almost simultaneously (again, at least by evolutionary standards) in archaeological sites in all four civilizations. For the first time, the historical evidence is abundant.

All of these civilizations demonstrated a belief that there was a special relationship between music and belief systems. Religions developed from the Neolithic animism we discussed in Chapter 10, in which mimesis of sound conjured the presence of the imitated animal or object’s spirit. According to Henry George Farmer, the presence of many gods was thought to be brought about through the mimesis of their sounds, and then later through music more abstractly. Such a belief is one example of totemism. Generally, totemism occurs all over the world, and involves a special relationship humans have developed with a spirit-being through, for example, an animal, an object or a plant (Haekel 2009). In our case, the sacred object or symbol manifested by a spirit would be the sound or music itself. In the urbanization of civilization, musical instruments diverged into popular instruments and professional instruments. The professional instruments largely followed the development of distinct classes, devoted especially to the practice of magic, religion and social purposes (Sachs 1940, 67).

Figure 11.7 Nefertari, Queen of Egypt, holding a sistrum. A sistrum is a tambourine-like idiophone.

Credit: Image by Laban66 from the Abu Simbel Small Temple in Egypt.

Figure 11.8 Danish Bronze Age lur (aerophone) from the thirteenth to fifth century bce.

Credit: Photo by Anagoria. Accessed July 21, 2017. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:-1300_Lure_Brudevaelte_anagoria.JPG. CC-BY-3.0. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/deed.en. Adapted by Richard K. Thomas.

In Mesopotamia, the oldest of the four civilizations, the god Ea had his name written with a sign that stood for drum. The dreaded sound of the drum signified his presence. Ramman commanded the thunder and the winds, and the reed pipe was his breath. The Egyptians built the elaborate temple services of Mesopotamia upon sounds and music such as these, the anima in all things (Farmer 1955, 231).

Gods ruled the world in Egypt before there were kings. The Egyptian god Osiris, taught the world the arts of civilization using discourse and music. His instrument was the sistrum (see Figure 11.7), an instrument specially dedicated to the goddess of music and dance, Hathor. Farmer describes clappers depicted in Egyptian pottery of the fourth millennium bce being used to conjure the god of harvest, Min.

Farmer also describes two influences Egyptians believed music had over humans: one, purely physical sensation, and the other, a special power, called heka or hike, similar to “what we understand by ‘spell.’” Farmer goes on to suggest that “it may be difficult to appreciate this hyperbole, and yet we still say ‘enchanting’ and ‘charming’ in our praise of music today without ever thinking that we are speaking in precisely the same way as did the ancient Egyptians, although they meant what they said” (Farmer 1957, 256–258). And yet, for everything we have explored throughout this book, we must note that, truth be told, we pretty much mean what we say: music certainly has the power to lead us into altered states of consciousness; it can literally be spellbinding. Theatre as a specific manifestation of music, has a similar power.

Figure 11.9 Upper Neolithic German clay drum from the fourth century bce.

Credit: Museum für Vor- und Frühgeschichte, Staatliche Museen Berlin, Photo Claudia Plamp.

Ancient Chinese believed that sound and music possessed a “transcendent” power, way beyond the sound itself. According to Laurence Picken,

The music of the seven-stringed zither tends constantly towards imagined sounds: a vibrato is prolonged long after all audible sound has ceased; the unplucked string, set in motion by a suddenly arrested glissando, produces a sound scarcely audible even to the performer. In the hands of performers of an older generation the instrument tends to be used to suggest, rather than to produce sounds.

Figure 11.10 Silver lyre from the Great Death Pit in Ur in Southern Iraq.

Credit: From Ur Excavations, Volume II: The Royal Cemetery. S.L. Wooley. Published for the Trustees of the Two Museums by the Aid of a Grant from the Carnegie Corporation of New York, 1934, 237.

Picken goes on to suggest the relationship between music and spirituality in ancient Chinese civilizations:

The belief in the power of music to sustain (or if improperly used to destroy) Universal Harmony was but an extension of the belief in the magic power of sounds. As a manifestation of a state of the soul, a single sound had the power of influencing other souls for good or ill. By extension, it could influence objects and all the phenomena of Nature.

These influences eventually found their way into Taoist and Buddhist traditions, and Picken suggests that “to a considerable extent this view of the nature of music survives even to this day” (Picken 1955, 86–88).

Arnold Bake maintains that the development of a music system in India bears a strong resemblance to that of ancient Greece, and developed about the same time. The music system that developed in India was strongly tied to Indian culture, philosophy and religion. Even today Indian music students do not separate music from philosophy, religion and cosmology. Such music, when properly practiced, can even break the cycle between birth, death and rebirth. The belief that music can influence destiny goes back to the oldest surviving form of Indian music, the music of the Vedas, centered around Vedic offerings and sacrificial rites. Such rites were considered to be of no value without not just the proper recitations, but also with the proper intonations.

Credit: Painting by Chen Hongshou.

The preceding sound is but one part of Indian cosmology, struck or manifested sound, or (áhatanáda). Struck and heard sounds cannot exist without their ideal counterparts, however. According to Bake, unstruck or unmanifested sound (anáhatanáda) “is identified with the creative principle of the universe in its transcendental form of the Hindu god, Shiva himself, as well as in its inherent form, the syllable OM, which is said to reside in the heart.” Such unmanifested sound exists not for enjoyment, but for liberation, to break the cycle of existence, “merging of the individual self with the creative principle of the Universe” (Bake 1955, 195–198).

We see in the emergence of all of these earliest civilizations a fundamental and essential relationship between music and spirituality. This relationship transcends simple analogy. It suggests belief systems carefully attuned to the powerful effects that music had on individuals and the conscious states of listeners. It suggests a recognition of the ability of music to fundamentally alter human brain waves, and, in doing this, human consciousness. Whether this effect manifested itself in the animism of the Mesopotamian gods of thunder and wind, the spells of the Egyptian power of heka, the imagined sounds of the seven-string zither, or the unmanifested sound identified with the Hindu god Shiva, the close connection between cosmology, spirituality and sound and music provides diverse support that even our earliest civilizations understood: the tremendous power that music has over humans.

The ability of music to directly stimulate the mind, without conscious attention on the part of the listener, was a powerful component of proto-theatre activities. In the development of all cultures we see a relationship between music, ritual and spirituality that transcends simple analogy. This relationship stimulates fundamental states of perception and consciousness that are not part of our normal human perception (reality, for lack of a better word). Humans continued to access these states through the music of ritual in the great early civilizations. Altered states of consciousness may have first manifested themselves in the dreams of primitive animals, and were then subsequently consciously created by shamans in ancient rituals. But they continued to find manifestations in the relationship between music and the spiritual world of these earliest known civilizations. The ability of music to directly stimulate the human mind, to alter its fundamental electrical patterns, all without human conscious participation, continued to profoundly influence and empower the proto-theatre type activities of humans in the cosmologies and ritual of the earliest great civilizations.

The Emergence of Written Language

For thousands of years, then, the relationship between music and language was inextricably bound together, whether through the group singing of our ape ancestors, or the dance and songs of the shaman’s ritual. This bond never undid itself as the oral tradition unfolded. However, those first drawings on cave walls and rock formations portended an extraordinary development in human cognition. They would pave the way for unparalleled advancements in our human ability to communicate. At the same time, such a development would require the pragmatic separation of music and idea necessary to achieve the most efficient communication.

The development of written language started with cave and rock drawings, and eventually those made on human-built structures. Eventually humans simplified the drawings into iconic images; that is, more generic versions that generally resembled the objects they represented, such as “man” or “woman.” Before long, early communication connected icons together with symbols; visual objects that no longer resembled their counterparts in the real world, but instead, stood for something else. Archaeologists have discovered such symbols in the same Neolithic sites at Jiahu, China, in which archaeologists discovered the bone flutes we explored in the last chapter, but from a later period, between 7000 and 5700 bce (Li et al. 2003) Other archaeologists discovered tablets containing symbols in a Neolithic settlement in Dipilio Kastoria in Northern Greece, dating back to 5260 bce (Facorellis, Cofronidou and Hourmouziadis 2014). In still another Neolithic settlement, archaeologists discovered symbols in the Great Danube Basin in Romania, originating 6000 to 5000 years bce (Merlini and Lazarovici 2008). It appears that the development of written symbols was a natural process that occurred independently in the early civilizations of Mesopotamia, Egypt, China and later in the Mayan culture of Mesoamerica. When a trait develops independently, it is a good sign that evolution has played a role, similar to those we found in the independent development of music.

Developing symbols such as those used in these early Neolithic settlements does not constitute communication in written language however. In the book Visible Language, Inventions of Writing in the Ancient Middle East and Beyond, editor Christopher Woods defines writing as

a system of more or less permanent marks used to represent an utterance in such a way that it can be recovered more or less exactly without the intervention of the utterer…. One must be able to recover the spoken word, unambiguously, from a system of visible marks in order for those makers to be considered writing.

(2015b, 18)

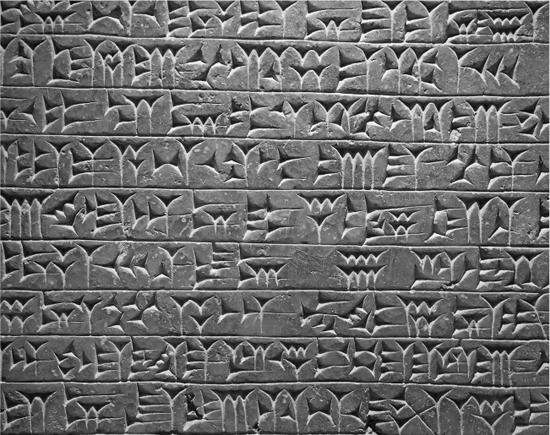

A more complex writing system is thought to have been created by the Sumerians of Mesopotamia around 3500 bce (Sumer is the first urban civilization in southern Mesopotamia, today southern Iraq). Yes, these are the same Mesopotamians the Bible would later accuse of attempting to build the infamous tower of Babel. They used reeds to inscribe marks on wet clay in a system we refer to as cuneiform that used numerals, icons (the written form are called pictographs) and symbols (ideographs).

Archaeologists uncovered the earliest from of cuneiform, which date back to about 3200 bce, at the temple in the precinct Eana in the sacred city of Uruk. Christopher Woods considers these earliest writings to be more administrative in nature, suggesting that the invention of writing was in response to practical, administrative needs (2015a, 33–35). These early writing systems were not invented to record speech. Jerold Cooper points out that “Livestock or ration accounts, land management records, lexical texts, labels identifying funerary offerings, offering lists, divination records, and commemorative stelae have no oral counterparts” (2004, 83). Hardly something worth singing about, unless performing from the phone book is your idea of a great time. To become fully formed writing, visible language would have to do a much better job of imitating its oral counterpart, speech. That would take hundreds more years.

Figure 11.12 Ancient Sumerian stone carving with cuneiform scripting.

Credit: Fedor Selivanov/Shutterstock.com.

The Transition from Oral Tradition to Recorded History

Over 500 years would pass before writing advanced to the point where it was capable of recording written speech (Woods 2015b, 20). Woods rightly describes writing as “one of humanity’s greatest intellectual and cultural achievements… (it) enhances capacity, enabling recording of information well beyond the capabilities of human memory” (2015b, 15). The advent of written language allowed our ancestors to record and pass down their stories from generation to generation in a way that the oral tradition clearly did not.

It is a curious coincidence that the transition from an oral tradition to a written tradition coincided with the end of a time when gods roamed the earth, interacting freely with humans. Written language is not as conducive to developing mythology as is the oral tradition. The oral tradition is subject to many flaws, distortions, and reconstitutions, all of which better allow myths to be created out of the very real retelling of feats and accomplishments of normal human beings. The Greek mythographer, Euhemerus (around 300 bce), was one of the first to assert that the ancient gods who roamed the earth were originally heroic men, greatly revered after their death. This interpretation of the emergence of gods is therefore known as Euhemerism, and we should note that not all researchers of the emergence of gods in all religions ascribe to this theory (Encyclopedia Britannica 2016).

It’s not so hard to imagine how these myths would have been formed in the oral telling and retelling of stories passed down from generation to generation. However, experiments at Northwestern University reveal that the way our human brains process memories may help explain how the expansion of stories into mythologies helped our ancestors make sense of the world around them. As we explored at the end of Chapter 10, memories are not simply data stored in the hard drives we call our brains. Instead the brain works to retrieve memories by recreating the original traces, the unique collections of neurons connecting with each other, that formed the original sensory perception. Every time we retrieve a memory, we must retrieve it all over again. We don’t typically get each reconstruction right. According to researcher Donna Bridge, a memory

can be an image that is somewhat distorted because of the prior times you remembered it…. Your memory of an event can grow less precise even to the point of being totally false with each retrieval…. Memories aren’t static. If you remember something in the context of a new environment and time, or if you are even in a different mood, your memories might integrate the new information.

(Paul 2012)

And so, memory itself is like the old telephone game, in which a story is repeated from one person to another, and the story at the end of the chain is shown to have varied significantly from the one originally told.

Now imagine how our ancestors passed these stories down from one generation to another with only human memory providing “storage” along the way. Not only would the story morph as it passed from one person to another, but also from generation to generation. Eventually, the exact specifics would prove to be less important than the lessons to be learned, the big picture that made preservation of the story so important in the first place. Exceptional human beings became gods, and their exploits ritualized into stories that were crafted in such a way as to be easier to preserve.

Of course, the groups interested in passing their stories down from generation to generation had a huge interest in having them passed down correctly. But without writing, their options were limited. One such option that could help structure more precise recall was music. As we saw in Chapter 10, music turns out to be a pretty good aid in helping to organize memories for easier retrieval. Rhythm, tempo and meter, as we have seen in prior chapters, are particularly good tools to help organize ideas so that the traces can be correctly retrieved later. It’s no wonder that music played so prominent a role in the passing of important stories from one generation to the next, and in the transition from ritual to autonomous theatre.

Nevertheless, in the later stages of the Bronze Age, written language would take on a significance absolutely necessary to the preservation of factual data. It ushered in the dawn of history, separating later times from prehistoric times. It allows us to know so much more about our ancestors, and to help reconstruct the past with much greater certainty that our reconstructions are correct. But it’s not very good at recording the music to which the ideas were originally attached. Somewhere along the way, the charioteer may have lost the chariot.

Conclusion: Lost in Translation?

In this chapter, we’ve considered the explosive growth of knowledge that accompanied the first four great civilizations of the Bronze Age. We considered how the spirituality of the Neolithic period manifested itself in the music of the gods of the Bronze Age, and we witnessed the near simultaneous development of the ability to more precisely record events in time afforded by the invention of writing. This transition from prehistory to history was neither fast nor homogeneous: while the oral tradition continued to be the primary method in which mythology developed and was passed down from generation to generation, writing took over as a more practical and efficient means to address the pragmatic needs of urban society. Eventually, however, writing advanced in a manner that allowed it to record human speech more precisely, and the oral tradition would slowly give way to written recordings of the ancient stories.

But something was lost in the transition from the oral tradition to written history. Oral traditions preserve the connection between music and idea. As Christopher Woods rightly points out “No writing system notates all of the linguistic structure of speech. Tone, stress, and loudness, for instance, are most often omitted in writing systems that are considered to be highly phonetic” (2015b, 21). Consider again, our discussion of the simple sentence we first presented in Chapter 1: “I’m going to the store.” How we musically perform that sentence has everything to do with how it is received. While it is true that the separation of music from idea created in various degrees in all writing provides us with tremendous interpretive opportunities in theatre, one imagines that it will be hard to capitalize on those opportunities if music is not considered to be a fundamental, essential, and integral component of the story in our earliest consideration of the story we hope to bring to life. Music is the chariot that carries idea. Without careful consideration, when we separate music from idea, we leave open the possibility that we give up a shiny new Maserati for a ’68 Rambler.

Ten Questions

- Name the first four great civilizations of the Bronze Age, briefly describe where they flourished and then identify four classes of musical instruments that developed in the Bronze Age.

- What is PIE, and how does it resemble the biblical story of the Tower of Babel?

- What is totemism, and how does it differ from animism?

- Name a Mesopotamian god that derived from animism and provided a voice for music. Tell us how to summon an Egyptian god.

- Why is the special power of heka so relevant to our consideration of music in theatre?

- Describe the transcendent power that the ancient Chinese thought sound to possess. How does this differ from áhatanáda and anáhatanáda in Indian music?

- What is the difference between an icon and a symbol, and why is this important to the development of writing?

- What is the most important characteristic of written language and what is its most important benefit?

- What does Euhemerism have to do with the telephone game?

- What is the advantage of writing over the oral tradition? What is the advantage of the oral tradition over writing?

Things to Share

- Part I. Write a short story that documents a traumatic experience you had at some point in your life that has shaped your life in profound ways ever since. Provide as much specific details as possible, but keep the entire story between 300 and 400 words. Form a circle in a group. Tell your story privately to the person to your right, and then have that person repeat your story privately to the person to their right. Repeat this process until the story comes all the way around the circle to the person on your left. Now have the person to your left publicly share the story to the whole group.

Part II. Turn your story into a ballad, that is, a song or poem narrating your story in short stanzas with a musical (sound) accompaniment. Consider adding a repeating chorus that stresses the most important ideas of your story, such as the important lesson you learned from the experience. Perform the ballad for the class after the person to your left shares the story with the group. - Bring a secular totem to class with you. It can be an individual totem that means something unique to you, or a group totem that you share with your family, social group or particular culture. Please do not bring religious totems, as we tend to have a harder time embracing, understanding and respecting religious totems than we do secular ones. You may discover that you have acquired an important totem that provides you strength in sport, in music, socially, or personally. Create a short, two- to three-minute ritual in which you share your totem with the class: lead us in a musical improvisation using whatever instruments are at your disposal, played by members of the group to celebrate your totem; give other members of the group iconic gestures associated with the totem that they can use to create improvisational dances to the music created by your musicians; write a short poem, song, or story to perform over the musicians and dancers’ improvisations. Venerate the totem while reciting your text. Above all, try to help us not just understand the power of your totem, but experience it; feel it, share it in all its power and glory.

Notes

1A large, flat area of land created by river sediment.

2We should also give a shout-out to a fifth early civilization that arose quite independently from the other four, Mesoamerica. Mesoamerica extended from central Mexico all the way to northern Costa Rica. We won’t include a discussion of this civilization here, largely because it emerged later than the first four civilizations, but in surprisingly similar ways: migration to the North American continent occurred around 20,000 years ago (National Geographic 2016); hunter-gatherer societies were in place by 11,000 bce, the transition to a more sedentary agrarian society occurred about 7000 bce, which gave rise to village farming by about 1500 bce, and the first great Mesoamerican civilizations, the Olmec, from about 1200 to 400 bce and the Maya, from about 1500 bce until about 1000 ce (Klein 1971, 269; Encyclopaedia Britannica 2016). Amazingly, we find evidence of a parallel development of cave art, musical instruments, shamanism, animism, altered states of consciousness, and eventually, writing, in the Mesoamerican civilization as we saw in the other four. Most importantly, we see the close relationship between music, ritual, mimesis and altered states of consciousness develop that we have so closely associated with the development of theatre (Looper 2009, 58–61). In the next chapter, we will explore the development of Greek theatre out of these closely connected entities. Remarkably, Mayan theatre developed with extraordinary similarities to Greek theatre. And the plays “pulsated with sound, both natural and man-made,” according to theatre historian Maxine Klein (Klein 1971, 272). The evolutionary forces that appeared to have given rise to music and theatre in the first four early civilizations appear to have also been at work in Mesoamerica!

Bibliography

Bake, Arnold. 1955. “The Music of India.” In The New Oxford History of Music: Ancient and Oriental Music, edited by Egon Wellesz, 194–227. London: Oxford University Press.

Bridge, Donna J., and Ken A. Paller. 2012. “Neural Correlates of Reactivation and Retrieval-Induced Distortion.” Journal of Neuroscience 32 (5): 12144–12151.

Cooper, Jerrold S. 2004. “Babylonian Beginnings: The Origin of the Cuneiform Writing System in Comparative Perspective.” In The First Writing: Script Invention as History and Process, edited by Stephen D. Houston, 71–99. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Donald, Merlin. 1993. “Human Cognitive Evolution: What We Were, What We Are Becoming.” Social Research 60 (1): 143–170.

Encyclopaedia Britannica. 2011. “Akkadian Language.” June 8. Accessed November 25, 2016. www.britannica.com/topic/Akkadian-language.

———. 2016a. “Euhemerus.” Accessed October 16, 2016. www.britannica.com/biography/Euhemerus-Greek-mythographer#ref25747.

———. 2016b. “Mesoamerican Civilization.” Accessed October 13, 2016. www.britannica.com/topic/Mesoamerican-civilization.

Facorellis, Yorgos, Marina Cofronidou, and Giorgos Hourmouziadis. 2014. “Radiocarbon Dating of the Neolithic Lakeside Settlement of Sidpilio Kastoria, Northern Greece.” Radiocarbon 56 (2): 511–528.

Farmer, Henry George. 1955. “The Music of Ancient Mesopotamia.” In The New Oxford History of Music: Ancient and Oriental Music, edited by Egon Wellesz. London: Oxford University Press.

———. 1957. “The Music of Ancient Egypt.” In Ancient and Oriental Music, edited by Egon Wellesz. London: Oxford University Press.

Haekel, Josef. 2009. “Totemism.” January 30. Accessed October 16, 2016. www.britannica.com/topic/totemism-religion.

Joshua, J. Mark. 2011. “Ancient History Encyclopedia.” April 28. Accessed November 25, 2017. www.ancient.eu/babylon/.

Klein, Maxine. 1971. “Theatre of the Ancient Maya.” Educational Theatre Journal 23 (3): 269–276.

Li, Xueqin, Garman Harbottle, Juzhong Zhang, and Changsui Wang. 2003. “The Earliest Writing? Sign Use in the Seventh Millennium bc at Jiahu, Henan Province, China.” Antiquity, March: 31–44.

Liu, Li, and Hong Xu. 2007. “Rethinking Erlitou: Legend, History and Chinese Archaeology.” Archaeology, 81 (314): 886–901.

Looper, Matthew. 2009. To Be Like Gods. Austin: University of Texas Press.

Mallory, J.P., and D.Q. Adams. 2006. The Oxford Introduction to Proto-Indo-European and the Proto-Indo-European World. New York: Oxford University Press.

Merlini, Marco, and Gheorghe Lazarovici. 2008. “Settling Discovery Circumstances, Dating and Utlization of the Tärtäria Tablets.” Acta Terrae Septemcastrensis, VII. http://arheologie.ulbsibiu.ro.

Paul, Marla. 2012. “Your Memory Is Like the Telephone Game.” September 19. Accessed October 6, 2015. www.northwestern.edu/newscenter/stories/2012/09/your-memory-is-like-the-telephone-game.html.

Picken, Laurence. 1955. “The Music of Far Eastern Asia.” In The New Oxford History of Music: Ancient and Oriental Music, edited by Egon Wellesz, 83–194. London: Oxford University Press.

Radivojević, Miljana, Thilo Rehren, Ernst Pernicka, Dušan Sljivar, Michael Brauns, and Dušan Borić. 2010. “On the Origins of Extractive Metallurgy: New Evidence From Europe.” Journal of Archaeological Science 37 (11): 2775–2787.

Sachs, Curt. 1940. The History of Musical Instruments. New York: W.W. Norton.

Shakespeare Quartos Archive. n.d. “King Lear—Shakespeare in Quarto.” Accessed September 25, 2016. www.bl.uk/treasures/shakespeare/kinglear.html.

Thomas, Richard, Matt Gowin, Kristy Lee McManus, Timothy Rogers, Justin Seward, Stephanie Shaw, David Swenson, and Jesse Dreikosen. 2002–2003. “KingLear@Ground Zero.” Accessed September 25, 2016. http://web.ics.purdue.edu/~zounds/KLAGZ/.

Violatti, Cristian. 2014. “Indo-European Languages.” May 5. Accessed November 25, 2016. www.ancient.eu /Indo-European_Languages/.

Woods, Christopher. 2015a. “The Earliest Mesopotamian Writing.” In Visible Language: Inventions of Writing in the Ancient Middle East and Beyond, edited by Woods, Christopher, Teeter Emily, and Geoff Emberling, 33–50. Chicago: Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago.

———. 2015b. “Introduction—Visible Language: The Earliest Writing Systems.” In Visible Language: Inventions of Writing in the Ancient Middle East and Beyond, edited by Christopher Woods, Emily Teeter, and Geoff Emberling, 15–28. Chicago: Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago.

Wright, Henry T. 1989. “Rise of Civilizations: Mesopotamia to Mesoamerica.” Archaeology January/February: 46–48, 96–100.