Chapter 10

Music, Mimesis, Memory

Introduction: Traveling Backward in Time

When I first started designing sound at Michigan State University, I apparently raised enough of a ruckus that people wanted me to come to their classes and explain what I was doing. That, of course, would be difficult, because I really didn’t have a clue. But I found an old tape in the sound closet that taught me a lot about how music works in the theatre. It contained recorded scenes from Elia Kazan’s Death of a Salesman. More importantly, it featured Alex North’s provocative score. The play opens with a haunting flute line underscoring Willy’s return from one of his many trips. Immediately we make a connection between the haunting flute line and Willy. We already feel his pain, and the play has barely begun. There were several more examples on the tape where Willy Loman’s theme underscored important moments, but the one that gave me my own bout of frisson was the last cue: Willy’s wife Linda talking to the now deceased Willy at his grave. I can still remember what she said: “Forgive me Willy, but I can’t cry.” And then we hear that flute line, haunting as ever. “It just seems like you are away on one of your trips.” I still get goosebumps thinking about how the music created the sense of Willy’s presence in that scene.

I would develop my first lectures about theatre sound around the flute in that play. It drove me to explore the use of thematic music in my first original sound score for Paul Zindel’s The Effects of Gamma Rays on Man-in-the-Moon Marigolds. For years, I would always look for ways to score the protagonist’s journey, inciting emotions at moments in which I knew it was important that the audience remember a scene from earlier in the story, and develop a strong emotional connection-identification with the protagonist of the play. It would be many, many years before I would begin to understand what I was doing, and how it actually worked. But learning about the magnificent gift of memory to composers and sound designers may possibly be the biggest leap one can have in learning how to empower a show with music.

In Chapter 3 we explored the great mystery of time. We bumped into the “speed limit of the universe,” 186,300 miles per second, and explored the phenomenon that as a traveler approached the speed of light, time begins to slow down, and at the speed of light, time stops completely. Science has borne out these theories, and demonstrated our ability to travel forward into the future. But we haven’t been able to find a way to practically travel backward in time. Or have we?

From Einstein’s famous thought experiments, we have learned that time itself is relative, subjective and unique to each individual.1 Because time is unique to each individual, we experience an alternate reality in our dreams that doesn’t conform to waking time. Another characteristic of our distinctly human subjective perception of time is that we routinely relive past experiences. We don’t just remember them, we re-experience them in our “mind’s eye” (and ear!). Memory researcher Endel Tulving first identified this unique human characteristic in 1972, eventually naming the phenomenon mental time-travel, or autonoesis (1972; 2002, 1). Our ability to mentally exist not just in the present moment, but to mentally travel back in time and relive past episodes of our lives is a distinct feature unique to human consciousness. You won’t catch your dog pining for the good ol’ days—he has a hard time knowing whether you left eight minutes or eight hours ago! And if that’s not bizarre enough, consider that Tulving also thought that our ability to remember the past also provided us the opportunity to project ourselves into future scenarios, which could be helpful in determining the best course of action.

We left the concept of our subjective perception of time for many chapters; other animals have no concept of time other than the present, for them there is no “subjective.” But in Chapter 9, we returned to our species, modern Homo sapiens. We once again considered our subjective perception of time in the altered states of consciousness of the shaman’s rituals, and how we could use music to manipulate that. We noted the similarities to our subjective experience of time in dreaming—except that our limbic system provides the stimulus in dreams. External sounds and sights stimulate us in ritual and theatre. In Chapter 9, we focused on activation and arousal. In this chapter, we’ll focus on the role that one facet of our subjective perception of time, memory, plays in human consciousness. In particular, we’ll focus on our ability to manipulate memory through music in ritual and theatre.

In Chapter 4 we learned that perhaps the most powerful way to manipulate our perception of time is through music, which we have literally described as “time manipulated.” In subsequent chapters, we have attempted to consistently bring the discussion around to this central theme: how we use music in theatre to manipulate human consciousness. Now, let’s consider how we use the powerful trio of music, emotion and memory to manipulate the conscious “present” of our audience in ways that transport them from the physical trappings of the auditorium to the imagined worlds of our plays.

We’ll begin, as always, by placing the development of our unique human memory capacity in the context of human evolution. We’ve already witnessed the last and “most recent” pieces of human genetic evolution fall into place in the last few chapters: anatomically modern human brains that first evolved about 200,000–300,000 years ago. Now we’ll explore what such a human brain can do. The human brain typically weighs about three pounds, as opposed to a chimpanzee’s, whose brain weighs about a pound2 (Smithsonian Museum of Natural History 2016). The human brain has much greater connectivity and plasticity than a chimpanzee’s, and at least twice as many neurons (Donald 2012, 271). An anatomically modern human brain contains 86 billion neurons (Azevedo et al. 2009, 535)! As we shall see, this capacity provides human beings with an extraordinary ability to process memories. Physicist Michio Kaku famously suggested, “The human brain has 100 billion neurons, each neuron connected to 10,000 other neurons. Sitting on your shoulders is the most complicated object in the known universe” (Egan 2015, 136).

Still, it would take this explosion of human mental capacity thousands of years to fully manifest itself. Memories, by their nature, don’t suddenly appear; they form over time as we accumulate things to remember. Once we have memories worth preserving we need ways to preserve them for future generations. Everybody wasn’t suddenly born with a library card! Human capacity for memory, may be the last to fully manifest itself evolutionarily, but, arguably, it is the one to have the largest impact on the development of civilization—and, of course, music and theatre.

We’ll pick up our story in the Neolithic, or new stone age, about 10,000 years bce. We’ll explore the transition from hunter-gatherer societies to more sedentary, agrarian-based societies. We’ll study the many kinds of memories necessary to the development of an oral tradition; stories full of ideas and music passed from generation to generation. All along the way, we’ll explore how composers and sound designers in theatre use memory to carry and preserve the stories and ideas of playmakers.

The New Stone Age

Members of our genus, Homo, had been roaming the earth for almost two and a half million years when they finally started to settle down almost simultaneously all over the world—in the Levant, North and South China, New Guinea and Ethiopia, eastern North America, and Mesoamerica.3 The shift was dramatic and swift: in a few hundred to a few thousand years, most humans settled down in primitive villages (Bocquet-Appel 2011, 560–561). Daniel Quinn famously dramatized the telling of this story in his 1995 book, Ishmael. In Ishmael, a telepathic gorilla tells the evolutionary story of biblical Cain and Abel. Abel was the hunter-gatherer “Leaver” displaced by Cain, the agrarian “Taker” (Quinn 1992, Part I, p. 41). Funny how biblical stories like this and Mitochondrial Eve4 seem to resonate in significant events that could only have survived by being passed down in stories through oral traditions for millennia. Later in this chapter we’ll discuss how music helps pass these stories down, and in the next chapter, what happens to the stories in the process.

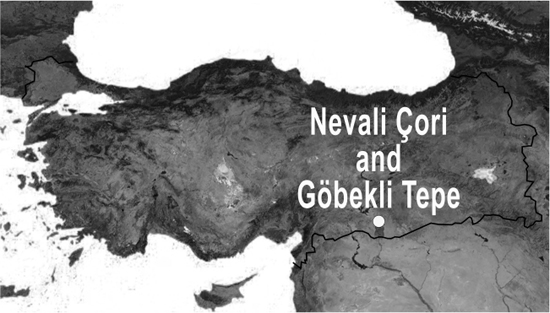

Regardless, conventional wisdom has always been that this “settling down” originated in new farming practices of developing agrarian societies, but that may not be how it started at all. The oldest permanent structure known to us is the temple at Göbekli Tepe (pronounced ɟøbekˈli teˈpe).

It dates back to about 11,500 bce. Archaeologist Klaus Schmidt discovered the site, and he and his team are convinced that it was the urge to worship that brought hunter-gatherers together at this site to build the temple (Dietrich et al. 2012, 679). Göbekli Tepe is rich with anthropomorphic figures that indicate a complex mythology, and a fairly advanced ability for abstraction and symbols (Dietrich et al. 2012, 684). The emerging consensus is that shepherds and farmers followed the building of these types of temples; the temple wasn’t originally built by an agrarian society (Curry 2008, 58).

Of course, there is ample evidence of music that seems to always be associated with these early rituals. At Göbekli Tepe, Klaus Schmidt points out that “The stones face the center of the circle-as at ‘a meeting or dance’”; a representation, perhaps, of a religious ritual. Pillars in the temple may represent priestly dancers at a gathering (Mann 2011). Schmidt’s team points out more generally, “a rich repertoire of PPN (Pre-Pottery Neolithic) dancing scenes sheds some light on the nature of early Neolithic feasts”5 (also see Garfinkel 2003). An especially good example is a bowl from a slightly later site, Nevali Çori, that shows two figures dancing with a turtle-like creature.

Figure 10.1 Location of Göbekli Tepe and Nevali Çori in Turkey.

Credit: Best-Backgrounds/Shutterstock.com. Adapted by Richard K. Thomas.

While we’re on the subject, we can’t help but note that the site is also known as possibly the birthplace of beer (Dietrich et al. 2012, 692), raising the specter of stone age “drugs, sex and rock and roll” type celebratory feasts releasing all sorts of dopamine in these early revelers.

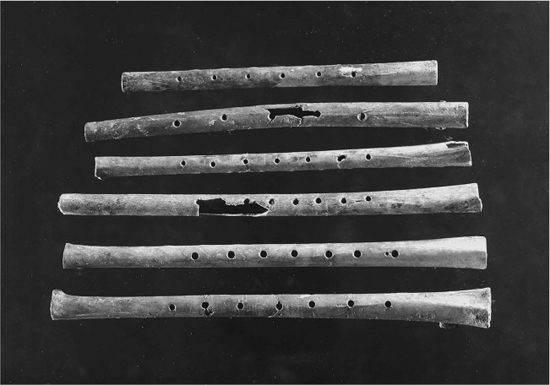

Across the globe in Jiahu, China, more evidence has emerged about the role and prominence of music in prehistoric rituals and spirituality. Over 30 bone flutes have been discovered in Jiahu, China, with an increased number of finger holes dating to about 5700–7000 bce.

The placement of these holes indicate that humans developed a much better understanding of the acoustic properties necessary to allow playing increasingly expressive and varied music. One of the flutes was so well preserved that a group of researchers was able to play it and analyze it, producing eight tones that closely resembled the modern melodic minor scale (Zhang et al. 1999, 366).

The discovery of a bunch of flutes may not seem like such a big deal to this discussion, but Zhang and his researchers remind us that

It is important in considering the possible role of these flutes in Neolithic society to recall that ancient Chinese tradition held that there were strong cosmological connections with music: that music is part of nature … mankind’s earliest practices of musical expression … probably took place in a ritual setting.

(1999, 367)

Credit: Image from Schmidt, Klaus, and Hauptmann, “Harald: Nevali Çori—Forschungen zum akeramischen Neolithikum im Vorderen Orient.” doi:10.3203/IWF/G-264. Published by IWF Knowledge and Media GmbH, Provided by Technische Informationsbibliothek (TIB).

Figure 10.4 Bone flutes from the Jiahu early Neolithic site in China.

Credit: Reprinted by permission from Macmillan Publishers Ltd: Nature, “Oldest playable musical instruments found at Jiahu early Neolithic site in China,” Juzhong Zhang, Garman Harbottle, Changsui Wang, Zhaochen Kong, Nature, 1999, Vol.401(6751), p. 366, copyright 1999. www.nature.com.

These very early examples of the relationship between music, rituals and spirituality continue throughout into the temples and the ritual practices of these early cultures. Henry George Farmer in the New Oxford History of Music suggests that “It is not improbable that music, or at least sound, stood at the cradle of all religion.” Farmer bases this assertion on the origins of animism in sound. Animism is a belief system in which all animals, plants and inanimate objects possess a soul. In such a worldview, it would seem natural that if one would strike an object, or blow through a flute, one would hear the spirit of the object express itself through sound (Farmer 1957, 256). In the same volume, Marius Schneider elaborates on this basic concept, suggesting that for primitive humans there was no distinction between religious and secular life. Music may have had its pragmatic functions, but would have also simultaneously been offered “to appease the spirit of the felled tree or the gods of the water he is crossing” (Schneider 1957, 42). It’s difficult to imagine in our fragmented lives such a holistic view of the world in which there were no divisions between music and the spiritual world, between music, dance and ritual. But this was a time when “gods were still wandering on earth.” For these neo-stone-agers, thunder was as strong an evidence that the gods were “drumming” as it was that the “angels were bowling,” which I was led to believe as a child.

The development of languages and more sophisticated music, would lead to the ability to tell more complex stories, which, in turn, led to elaborate mythologies. The only way to preserve these stories would be for each successive generation to learn them, to memorize them. Fortunately, anatomically modern Homo sapiens had that significantly larger brain, an almost unlimited ability to retrieve memories for our stone age performers. In the next section, we’ll examine the complex ways in which our brain operates in order to store and retrieve memories, the role that music plays in memory, for us as composers and sound designers.

Memory

Introduction

In his extraordinary book, This Is Your Brain on Music, Daniel Levitin suggests that “Memory affects the music-listening experience so profoundly that it would not be hyperbole to say that without memory there would be no music” (2007, 166–167). We can make the same argument about the relationship between music, memory and theatre. We have seen the ability of the sleeping mind to conjure up memories on its own in our dreams. The sleeping mind constructs and fabricates dreams in seemingly random orders, and often for unknown purposes, presenting an altered reality that may or may not inform our waking world decisions. We have also seen in the rituals of the shamans the ability to induce dreamlike worlds, blending the unique memories of each audience member into new perceptions that bear a strong resemblance to the memories of everyone in the group—and those of their ancestors. Creating such memories must have provided shamans with extraordinary power to influence, control and shape the actions of large groups. This, in turn, may have allowed large groups to accomplish much more than smaller tribes could accomplish on their own. One way to create those group memories, and make them seem real, was by using music to carry the stories and emerging mythologies. Music and ritual surely must have had adaptive value that would ensure not just survival of our species, but the explosive growth that took place from the Neolithic age through the first large civilizations.

Distinguished professor James S. Nairne leads Purdue’s Adaptive Memory laboratory. He suggests three possible characteristics of memory that our “stone age” brains must have developed in order to enhance our chances of survival. First, memory must be more than an ability to record the past; recalling memories must be useful for some present purpose. Second, in order to survive, we can’t just randomly recall memories; there must be some mechanism that precipitates the appropriate memory for the current situation. Third, such a mechanism must have evolved in such a way so as to prove useful in recalling memories that are not just related to the present context, but that are useful in dealing with the present context (Nairne and Pandeirada 2008, 240). We could consider these principles as three questions one must ask oneself in scoring a play:

- Why do we want to generate and subsequently recall this memory?

- How will we cue this memory?6

- How will recalling this memory enrich the audience experience in the present moment?

Keep these important characteristics in mind as we investigate each memory system.

There’s not much difference in the basic requirements of the shaman and modern sound designers/composers when it comes to engaging our audience’s memories in the perception of ritual or theatre. Basically, we must successfully manage three processes. First, we must provide sensory stimuli in such a way that the brain can process and encode it in a form useable by the memory systems of the human brain. Second, we must effectively be able to convince the brains of our audience to store the memory in useful ways. Finally, we must be able to manipulate the consciousness of our audience to retrieve the memory at appropriate moments both during the performance and afterwards, as they hopefully reflect on the experience. To do these three things, we must come to grips with how our anatomically modern Homo sapiens brains process memories.

In the next sections, we will examine the different types of memory systems commonly thought to be used by the human brain. We must point out before we do, however, that we are no longer dealing with individual, isolated components of the brain. We now investigate memory systems that utilize smaller components that may serve multiple functions: “Memory systems are organized structures of more elementary operating components,” says Tulving (2002, 6). The simple fact that memory uses so many different components has made studying memory very complex, and there is still much more research to do. Many theories exist side by side, some mutually supportive of each other, some contradicting.7 We’ll try to stick to theories that have achieved some measure of validation and apply directly to the art of the sound designer and theatre composer. Of course, the advantage of having incorporated pragmatic conceptions of how memory works in my sound scores for 40 years will serve as an unlikely but hopefully welcome demonstration of the salient qualities of these theories. If not, they may still serve as interesting example of how these theories found their way into one person’s aesthetic of theatre sound design and composition.

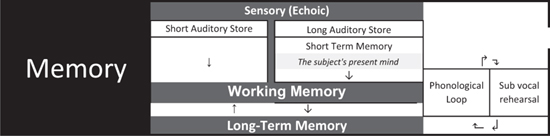

In 1968, R.C. Atkinson and R.M. Shiffrin proposed that there were three distinct parts of memory: sensory (echoic) memory, working memory, and long-term memory (Atkinson and Shiffrin 1968). While there has been an overwhelming amount of research into the different types of memories, the basic concept has survived in some form through the present day (albeit with its own share of variants and controversies). We’ll consider each type of memory in the next sections.

Sensory Memory

We’ve introduced the auditory form of sensory memory, echoic memory, in Chapter 8, noting that the auditory cortex in the temporal lobe holds the sounds transmitted by the ear just long enough for other areas of the brain to process it, primarily for pitch, timbre, and to determine basic relationships such as consonance and dissonance.

Nishihara and others suggest that echoic memory has four defining characteristics:

- You don’t have to be paying attention to the sound in order for it to be stored in your echoic memory; it gets stored there whether you pay attention to it or not.

- The information stored in echoic memory is sound only, transmitted directly from the sensory organ of the ear.

- The information stored there has a finer resolution than other memory systems; this is the closest thing we have to a “tape recorder” in our brains.

- Echoic memory does not last long (Winkler and Cowan 2005, 3; Nishihara et al. 2014, 1).

Recent research has suggested that sensory memory may be involved in a more sophisticated version of the habituation response we first encountered in Chapter 2. In one particular testing paradigm, called the Mismatched Negativity Event Related Potential (MMN), an auditory stimulus is presented repeatedly at relatively short intervals. The subject is typically engaged in a distracting activity and told to ignore the stimuli. After a pause in stimulus, which depends on the nature of the test, the stimulus is repeated once again as a reminder, and a different stimulus is then introduced that deviates from the original. Electrodes planted non-invasively on the scalp allow researchers to measure unconscious and conscious brain activity. From this test, researchers can tell how long the particular stimulus persists in echoic memory, and whether the deviant stimulus activates arousal; that is, whether other parts of the brain, particularly the frontal lobe, gets involved in bringing the deviant sound to our conscious attention.8 Winkler and Cowan found that the limit of echoic memory under these circumstances was less than 11 seconds. Others have proposed different models, with different time limits based on how various stimuli were presented and analyzed (Winkler and Cowan 2005). MMN remains a somewhat controversial technique, but also continues to find many applications in cognitive neuroscience. Regardless, there does not seem to be much controversy that changes in pitch, duration, loudness and spatial location can all elicit a change-related cortical response, with subtler changes taking longer to register, and eliciting smaller amplitude responses (Näätänen et al. 1993, 436). In other words, when our auditory environment changes, we notice. The smaller the change, the longer it takes to attract our attention, and the less likely it will be to do so (Tiitinen et al. 1994).

In Chapter 2, we were dealing with the most primitive members of the animal kingdom when we considered unconscious, physiological startle response and habituation. We now see a much more sophisticated version than the unconscious physiological response of our more primal brain circuits. Much more subtle habituation responses occur when the sound persists in echoic memory without involvement of the frontal lobe. Likewise, arousal occurs when a major change in the sound environment grabs our attention, that is, involves other parts of the brain in a quick reaction. The stimulus enters our consciousness, where our frontal lobes get involved in analyzing the sound. In the hundreds of millions of years since startle and habituation first manifested themselves in primitive animals, our sensitivity to changes in our auditory environment has increased quite a bit. As sound designers and composers, we can arouse our audience with much subtler mass and dynamic effects than the startle effect. We can also use changes in color, rhythm, line, space and texture to arouse our audience and focus their attention. But still, the basic premise is the same: our attention is unconsciously aroused when our auditory environment changes.

The ability to use sound to grab the attention of an audience is both a tool and a pitfall for sound designers and composers. There are times when we need to draw the attention of our audience, and there are times when we need to avoid drawing attention. A playwright may introduce a new character into a scene, which introduces a new auditory rhythm and color and so forth, and that will draw focus. A composer or sound designer introducing a new sound, or changing the ambience in a scene will have the same effect—oftentimes distracting the audience from the dramatic scene. Putting the loudspeaker in the wrong place (e.g., on the side of the proscenium) can draw the attention of the audience (and the director!) to the sound without them even knowing why! As we discussed in Chapter 2, sound designers and composers need to be very cautious about where and when they introduce changes in the auditory environment. When used intelligently, however, changing the auditory environment can work as very powerful attention getting devices.

I remember my friend Abe Jacob telling me the story of how he got the building engineer to turn off the air conditioning system during A Chorus Line on Broadway, just before one of the quietest moments in the show, the Paul Monologue. The change in mass clearly drew the focus of the audience. Abe told me “it … made it a little bit uncomfortable in the house, a characteristic that director Michael Bennett loved, ‘That’s what we want them to feel—the same uncomfortableness that Paul is feeling onstage’” (Thomas 2008, 55). Usually we want to manipulate focus in just this way: unconsciously. The audience doesn’t consciously hear the change in sound, but finds its attention suddenly more consciously focused. It’s when the audience becomes aware of being manipulated that the emperor suddenly has no clothes and the audience is pulled out of the dramatic world of the play. Learning how to analyze the story and the text is one of the most significant abilities that we need to acquire in order to understand when to draw focus, and when to habituate, when to do it very consciously, and when to work one’s magic very subtly.

Long Auditory Store/Short Term Memory/Working Memory

Sensory memory, which we discussed in the last section “allows the memory of … things to linger while we think about them” (Cowan 1997, 51). Cognitive psychologist Nelson Cowan suggests that the rich, highly detailed mental image of the sounds we hear only lasts for a few hundred milliseconds in this sensory memory. Cowan calls this short auditory store. However, some parts of it, such as color, pitch or loudness last significantly longer, up to as much as 20 seconds. Cowan called this long auditory store. Cowan considered both types of memory to be types of sensory memories.

Cowin’s long auditory store bears some resemblance however, to another concept called short-term memory. George Sperling first proposed the concept of short-term memory in 1960, noticing in his experiments that subjects forgot visual stimuli within about a quarter of a second, but could remember about four specific bits of information like letters or numbers for longer periods of time (Sperling 1960, 8). Even though later experiments determined that the sensory memory was longer for auditory stimuli, the short-term memory for storage remained at about four items (Cowan 2015, 8). Cowan describes this short-term memory as “the subject’s present mind” (Cowan 1997, 77). So we notice right from the start that there is some overlap, and, as always, controversy, between the concepts of sensory memory and short-term memory.

Beyond these limited capacities, the mind is capable of “juggling” a few different things at once, focusing first on one item, then on another, then on another, and then back to the first item. So the conscious mind is able to hold somewhat more than four items in its short-term memory. George Miller, in a landmark 1956 paper called “The Magic Number Seven, Plus or Minus Two,” noted that human beings can maintain about seven discrete items in their brain at one time—plus or minus two (1996)! Baddeley and others discovered in 1975 tests that subjects could only recall as many items as they could repeat in about two seconds (1975, 575), and many others have subsequently confirmed these findings (Cowan 1997, 82). Robert Glassman suggests that the consensus today of cognitive psychologists is that we are able to hold about six items in what has come to be known as our working memory at a time. At any moment, our working memory will hold the last three or four items we heard (sensory memory). The other two items get refreshed as part of our two seconds of short-term memory, as long as we keep mentally repeating the items in our mind (Glassman 1999).

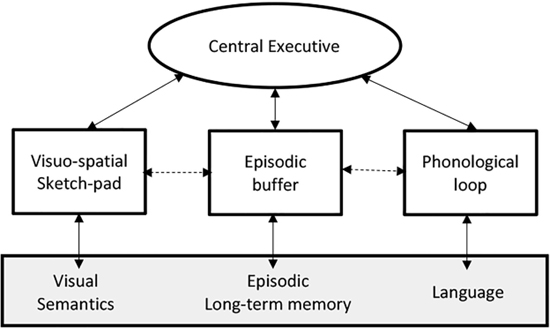

Atkinson and Shiffrin first proposed the concept of a working memory, which Baddeley defines as the “system or systems that are assumed to be necessary in order to keep things in mind while performing complex tasks such as reasoning, comprehension and learning” (Baddeley 2010, R136). Working memory differs from short-term and long auditory store in that working memory involves the entire “thinking” process, while short-term and long auditory store are simply the stored data. Baddeley overhauled the Atkison/Shiffrin concept of a working memory around the concept of the Central Executive, a system in the brain that controls how and where we focus our attention.

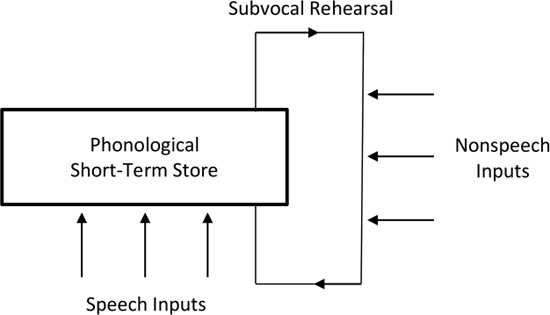

How long we are able to hold information in our working memory depends on how we attend to it. In 1984 Baddeley proposed a neural circuit that we now call the phonological loop.

The phonological loop allows us to repeat words over and over again subvocally, while our Central Executive system processes the information. Of course, there is also a visual correlate of the phonological loop that interacts with the Central Executive, called the Visuo-spatial Sketch Pad.

Figure 10.5 Baddeley’s model of the phonological loop.

Credit: Derived from Baddeley, Alan, Vivien Lewis, and Giuseppe Vallar. 1984. “Exploring the Articulatory Loop.” The Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology. Section A, 36: 2, 233–252, doi:10.1080/14640748408402157.

Levitin sets the capacity of our phonological loop at between 15 and 30 seconds (Levitin 2007, 155). You’ll notice that you use your phonological loop all the time to do things like remember a phone number, mentally (subvocally) repeating the digits over and over until you are confident you have them memorized. This phonological loop even works with visual information—it doesn’t make a difference whether you hear the phone number or see the phone number, when you try to remember it, you will typically subvocally repeat the digits over and over again—rather than attempt to visually keep the digits in your mind. Some research suggests that brain components that support the phonological loop include the right middle and inferior temporal lobe and the left hippocampus (Rudner et al. 2007).

The curious thing about this phonological loop is that David Kraemer and his team of cognitive psychologists have discovered evidence that the same phonological loop we use to rehearse those phone numbers into our long-term memories is where songs get “stuck in our heads,” the auditory cortex and associated areas in the temporal lobe. Some people call them “earworms,” from the German ohrwurm. The more scientific types describe earworms as Involuntary Musical Images (INMI) (Beaman and Williams 2010). Others describe the whole process of what gets stored in the phonological loop (including earworms) as Auditory Images (Kraemer et al. 2005, 158). But the interesting part is that while Baddeley’s 1984 team just used words in their tests and research of the phonological loop, Kraemer’s team found auditory imagery worked for instrumental music as well as words. But there was one important difference: when there is semantic meaning involved in the phonological loop, only the auditory association cortex got involved.9 When the earworm was purely instrumental, the primary auditory cortex also got involved. Kraemer’s team notes that the visual cortices function in a correspondingly similar way (Kraemer et al. 2005).

I’ve known about music getting stuck in this continuous loop in my brain since I was very young. Levitin suggests that musicians and people with OCD (obsessive-compulsive disorder) are more likely to experience earworms10 (Levitin 2007, 155). From my very first experience with The Effects of Gamma Rays on Man-in-the-Moon Marigolds, I tried to incorporate “hooks” in my theatre music. I first wanted to make sure that the audience left the theatre with the hooks repeating in their phonological loops (of course I didn’t know what to call it at the time), and then I wanted to attach important ideas in the play to the hook. In Marigolds, I co-opted Tillie’s Theme into a repeating hook that underscored Beatrice’s (Tillie’s mom) descent into a nervous breakdown in the resolution of the play. I attached the lyric “What’s left for me?” to the hook, and repeated it over and over again as the stage lights faded on the end of the play. The contrast between Tillie’s tenacious idealism and Beatrice’s self-destructive narcissism had given me a lot to think about, and I wanted to plant the same seed in the minds of the audience as they left the theatre. Beaman and Williams have a (pardon the pun) catchy name for the passing on of earworms such as this: memetic transmission (Beaman and Williams 2010, 638). In advertising, we typically attempt to attach a brand name to the earworm (meme); in theatre sound scores, we hope to attach the important ideas of the play.

I consider the opportunities to write music that I intend to insert into the audience’s phonological loop on the way out of the theatre to be relatively few and far between. You get a lot of those opportunities if you write musicals, or if you compose for straight plays that have songs in them. Shakespeare is full of opportunities because virtually every one of his plays has a song in it from which you can parse themes and motifs. In straight dramas, you are more likely required to use hooks much more subtly, as you can’t overpower dialog with underscore using a strong melody. You’ll often have your only chances during scene changes and special moments in which there is no dialogue but strong emotion. Regardless of where the opportunity falls, the best advice I can give is: be careful.

Earworms are funny things, if you think about some of the ones you’ve had. I won’t mention any names, but most everyone has experienced a really awful song that got stuck in their head at the grocery store or doctor’s office. Earworms have no taste. Some of the melodies that get stuck are simply banal. Composers need to take care when writing hooks to keep them unique and interesting yet insanely memorable. The San Francisco–based Exploratorium website suggests using repetition and/or unique time signatures to create earworms (Exploratorium 2016). And there might be something useful in that advice. Repetition almost always helps to get something stuck in our memories; unique time signatures go a long way toward keeping a hook unique, fresh and interesting.

Daniel Levitin suggests that “style is just another word for repetition.” It’s not just the strict looping of precise auditory events that helps a tune get stuck in our phonological loop. The tune and the “hook” will observe very specific laws of music that we’ve heard before. It will reference in our memory all the music we’ve heard before that approximates the style of the tune and hook. Levitin describes this approximation as the schema of the style, the general set of rules that the style repeats. We take advantage of all this “hidden” repetition, just by virtue of writing in a particular style with which the audience is familiar (this is, by the way, one of the reasons I advocate composing underscoring using modern scoring techniques rather than following strict period; an unfamiliar period style may pull us ever so subtly out of total immersion in the scene).11 Levitin goes on to suggest that it’s not just strict repetition of the rules of a particular style that help us get a hook lodged into the phonological loops of our audience. It’s the subtle variations that make our hook unique that help to create the arousal necessary; it’s how we violate the schemas of the style (repetition) that help to set the hook. As they say in This Is Spinal Tap, “it’s such a fine line between stupid and clever.” Too much variation, and the hook will draw focus; too little and the hook becomes banal and doesn’t set, or sets in a most irritating manner.

Early in my career, I crafted tunes while playing the guitar, like Tilly’s Theme in The Effects of Gamma Rays on Man-in-the-Moon Marigolds. But I soon realized as I became more sure of myself as a composer and sound designer that sitting at a musical instrument was perhaps the worst place to develop a strong, memorable tune. I was a slave to my musical instrument, my facility on the instrument dictating melodic choices. Once I discovered this, a whole new world of composing tunes and themes opened up for me. I learned to take walks, go jogging, engage in some form of physical activity while turning the melody over in the back of my mind. The natural rhythms of my body would help structure the tune and teach me what worked and what didn’t. The physical act of walking provides the mechanical tempo that forces the hook into an interesting rhythm. The physicalization of the rhythm also helps develop a hook that entrains the audience. If there’s a lyric or text such as in Shakespeare, I’ll memorize it before I head out so I can make sure to be true to its prosody. Often times both the dominance of the physical tempo of walking, and the scansion of the text of the language will force a hook into my mind with unusual rhythms and meters that nevertheless feel entirely organic. Those are the hooks that seem to stick the best and avoid the dreaded banality.

I have a rule that when I’m developing a hook, I don’t write it down. If I don’t remember it when I come back to work on it later, it wasn’t good enough. A good tune will come back and haunt me, a good indication in my mind that it will do the same to my audience. Often when the melody does come back, the part that comes back is musically strong—a “hook,” and the part I can’t remember is the weak part. My thinking is that if it wasn’t strong enough to stick in my mind, how do I expect it to get stuck in the phonological loops of the audience?

There simply are no explanations, however, for the moment when an amazing, memorable, hummable, catchy, extraordinary hook first appears. I never seem to remember the moment a great tune comes into my mind. I know that I often have to work it over and over again to get it exactly right, but my best tunes seem to have always come from inspiration, from deep within, not from craft. For me, the moment when the hook finally seats itself in my mind is always a special one. You massage and massage melodic ideas, and suddenly they appear, fully formed, and you know they are good, they are going to stick, and the audience won’t mind them sticking. I remember the exact moment my hook for the ESPN Indy 500 television series first appeared. I had just walked past the University Bookstore close to our campus. Barely five seconds long, I found the hook outside the campus bookstore during a walk. It was just suddenly there; later my partner Michael Cunningham and I would develop that hook into all of the other scoring for the different shows in which it was used. A curious footnote to this ESPN story: I had planned a simmering chord progression that would create anticipation as it underscored the opening VO (voice-over). The idea was that the hook would erupt after the VO when the logo flew onto the screen. I thought my hook was strong and memorable and would not wear thin when it was repeated throughout the series at commercial breaks. Michael considered it and added a countermelody under and slightly after that exploded the energy exponentially. To this day, if that hook pops up in my phonological loop, Michael’s countermelody is there as well. I credit Michael with making good brilliant.

There’s no telling when and where the hook will happen; all I know is that I have to put the dramatic moment in my own working memory, and hold it there until the hook arrives. The tune for the opening theme for our Milwaukee production of John Pielmeyer’s Splatterflick came to me in the shower (of course!). I was playing cards with my family when “The Doxie over the Dale” that Autolycus sings at the top of Act IV, Scene 3, in the Purdue production of Shakespeare’s Winter’s Tale came to me. What I have learned about creating melodies, themes and tunes, is to somehow hold them in my mind even as I go about my workaday life, and to hold them there until they come out right. This can take a couple of days or a week. It’s usually the first thing I do for a show, if the show is going to require a hook, because so much other material will often derive in some way from that melodic material. And if I have learned one thing about being an artist, it’s that a life as an artist will involve wonderful, thrilling hills of seemingly divine inspiration, in which you create sound and music beyond what you imagine you are capable of composing. You also learn that you do not bank on inspiration. In between the hills of inspiration, you make sure that you have learned your craft so meticulously that you can manage any deadline with something that may not be quite as brilliant, but will certainly be quality. Inspiration may make iconic composers such as Bach or Beethoven, but craft will keep a theatre composer working during the valleys.

Figure 10.6 Baddeley’s Model of the Central Executive has proved both “durable” and “widely used.”

Credit: Derived from Baddeley, Alan. 2010. “Working Memory.” Current Biology R136–R140.

You may have noticed that the length of an earworm is considerably longer than the two-second span that Baddeley and others discovered were able to be held in active memory in their 1975 tests, but about the same length as Cowan’s long auditory store. How is it that we can hold so much more than two seconds in our active memories? To accommodate this characteristic, Baddeley modified his model of the working memory to include the ability to load long-term memories into an episodic buffer.

We store and load items to and from our long-term memories into a buffer that allows us to hold more items than in our immediate focus. Cowan proposed a similar solution, that the central executive could load items from long-term memory into the working memory while it needed them (Cowan 2015, 7). The trick here is that if we can organize smaller bits of information into a familiar group, our brain will only count the group as one item. In my classes, I offer up a simple example. I show the class the following for a couple of seconds:

FAT DOG EAT PIG

And ask the class to try to repeat what they just saw. Of course, they have no problem, after all, they only have to remember four words! I then show them the following:

FDEPAOAITGTG

And ask them to repeat that. Even the best have problems remembering more than about 7 (OK, +/–2) letters. Nobody gets all 12. Students are surprised, then, when I reveal that both examples contain the same letters. The test above is an example of a phenomenon called chunking. According to George Miller’s 1955 hypothesis about the “Magic Number Seven, (+/–2!)” our working memory can hold a finite number of “chunks” of information at once, not bits: “the span of immediate memory seems to be almost independent of the number of bits per chunk” (Miller 1996, 349). Daniel Levitin defines chunking as “the process of tying together units of information into groups, and remembering the group as a whole rather than the individual pieces” (Levitin 2007, 218). This means that we don’t remember all of the details (which takes up less space/time in our short-term memory), just the ones that are important to the chunk and the present situation.

What does all this have to do with sound scores and theatre? According to Michael Thaut, we use the same mechanisms of chunking in music as we use in language. Because of this, the tempos, meters and rhythms of music turn out to be a really good way to group and chunk verbal information. That’s how children learn their ABCs, using the letters of the alphabet as the lyrics to a well-known melody. The melody and melodic rhythm of the song organize the letters of the alphabet into more easily remembered chunks, allowing music to facilitate learning that persists even beyond the song, when children use the alphabet in real life12 (74–75).

The apprehension of such a large structure as plot successfully depends on manipulating and organizing structure to facilitate easy remembering of important elements of the play by the audience. Rhythm makes it easier for us to remember verbal material, and the elements of rhythm do their work entirely within our working memory (Thaut 2005, 6–8). When we use music to score lyrics and dialogue, we make it easier for listeners to chunk elements of the story together, first into smaller units of action. Chunking the individual scenes allows us to put those chunks together into larger units of scenes and acts, enabling us to hold the whole story in our minds as it unfolds. If you don’t think we chunk plays together in this way, just ask somebody what the play was about, and watch how they piece the story into manageable chunks—not bits—of story. If you don’t think chunking in plays is a musical phenomenon, imagine listening to the entire play unfold in a rhythmically unvarying monotone, and consider how much of that you would be able to remember—even of the part before you fell asleep from endless habituation!

Understanding how to organize the sound score of the play in a way that chunks the story in meaningful ways is perhaps the hardest task I encounter when helping new students learn about sound scores. Students instinctively concern themselves with how the sound cue works in the moment, which is a good and critical first step. Our most immediate chunking goal is to create a sound score that organizes the moment in such a way that the audience comprehends it in chunks rather than isolated bits of information. The sound that orchestrates the moment must work with the rhythm of the scene in order to create salient chunks of story. For example, we might describe the salient chunk in the opening scene of Hamlet as “those guys see Hamlet’s father’s ghost.” In scoring this scene to embed the chunk into long-term memory, then, we must correctly identify where the most important parts of the key elements of the chunk start and end in the scene, and then make decisions about how we want to bracket the chunk with sound. We must identify the most important moments inside the chunk that will cement the gist into our memories. There’s a lot to think about in terms of using sound to create a meaningful chunk in the first place.

But because students often have little understanding of dramatic and musical structures, thematic devices and the underlying experience of a play the author has in mind, they leave the individual chunk and treat the next one as if it exists in a wholly different play. Our next goal in creating an effective sound score is to put individual chunks together into a larger, more all-encompassing chunk, which will again make it easier to keep the whole story in one’s mind in the present moment of the story. What does the first ghost scene have to do with later scenes in the play? If we can get the audience to effectively encode a story chunk into their memory, when and how do we recall it in subsequent scenes so that the audience codes the old and new chunks into a larger, more all-encompassing chunk? How do we vary the recurring chunk to code the new chunk we are forming?

Consider the later scene in Hamlet when the ghost reappears in Hamlet’s mother’s chambers and tells Hamlet: “Do not forget: this visitation is but to whet thy almost blunted purpose” (Hamlet, Act III, Scene 3, ll. 126–155). Now we have an opportunity to use music to recall the old chunk about when those “guys saw Hamlet’s father’s ghost,” and that other one about “when the ghost told Hamlet to revenge the ghost’s murder.” We can then use our sound score to combine the earlier chunks with a new one about “don’t forget to revenge the ghost’s murder” into a larger chunk we might call “why doesn’t Hamlet revenge his father’s murder?”—which, coincidentally, is a subject that fills volumes of discussion in library sections of dramatic theory and criticism. But unless students know enough about theatre in the first place to visit this library section, or possesses strong play analysis tools, they might have a hard time understanding where and how to look. This is what we mean by sound being a powerful tool in telling the story. It’s not just about finding a good sound effect for the moment.

As critical as chunking is to our ability to tell and comprehend stories in theatre, consider how important it must have been before there was modern theatre, with its scenery, costumes and lights. Consider how important it was before the advent of written language, where, without some extraordinary way to chunk the story into memorable units, the story would be lost to subsequent generations. In the time between the advent of oral language, and the introduction of written language, the chunking ability of music was an important component of what we now call the oral tradition.

It’s not hard to imagine a progression then, from the first conceptualization of spirituality, expressed in ritual, propelled by the shaman’s rhythm, and experienced through excursions into altered states of consciousness. Eventually these rituals produced stories, and over a long period of time, mythologies of gods who roamed the earth, preserved in the songs handed down from one generation to another through oral traditions. The evolutionary psychologist, Matt Rossano, carries this progression one step further, suggesting that ritual behavior did not just provide one of the roots of theatre, but led to the development and evolution of human working memory in the first place. In Rossano’s view, ritual behavior “was a critical selective force in the emergence of modern cognition” (2009, 244). And up to this point, we have found very little to suggest that music was not as central to that ritual experience as human behavior can get. And eventually to theatre.

Long-Term Memory

If we rehearse (repeat) what’s in our phonological loop long enough, we put it into long-term memory. On the other hand, a good scare will pretty much pop the event directly in. We’ll come back to this later. Long-term memory is our ability to more or less permanently store our memories for a few days, weeks, months, years, or the rest of our lives. In the last section I suggested that the opportunity to create tunes, hooks and earworms that get stuck in the audience’s phonological loops are few and far between, unless you are writing a musical, or plays that have a lot of songs in them, like Shakespeare. We will much more likely be required to compose sound scores in which we try to create a lasting memory of the dramatic moment rather than a lasting memory of a particular tune or hook.

Marilyn Boltz and others have demonstrated that for scenes involving background music, it is more typical that our audiences cannot recall a given tune if it is played separately from the movie. However, they can recall it when it is played back with the movie attached to it (Boltz, Schulkind and Kantra 1991). It is the underlying mood that seems to become part of the long-term memory rather than the mechanics of a specific tune. Boltz and others’ research demonstrated that background music effectively improved the ability of the audience to recollect a scene (1991, 602). We’ll discuss why later in this chapter, but we should recognize that this is all a good thing. Why? Our working memories are hopefully focused on the dramatic moment, rather than the music itself. You will often hear sound designers suggest that most of our work goes unnoticed. With background music, when we do our jobs well, the full attention of our audiences focuses on the dramatic moment. Unfortunately, it does make it easier for the good folks that pass out theatre awards to overlook our work, though.

Creating and Retrieving Long-Term Memories

Even if we are able to hold larger ideas in our minds through the process of chunking, we still must effectively store the chunk in the audience’s long-term memories, so that we can trigger recollection later at an appropriate moment of the play. One effective way to create a lasting memory is to incite a strong emotional reaction to the moment. Michael Thaut states it plain and simple: “emotional context enhances learning and recall” (2005, 76). Baddeley seemed to get to the heart of the matter when he suggested that “processing a word in terms of its perceptual appearance or spoken sound is much less effective for subsequent learning than encoding the material on the basis of its meaning or its emotional tone” (Baddeley 2010, 5). The ideas are important, but if you really want your audience to remember something, escalate the emotion of the moment. And one of the best ways to escalate an emotional reaction is to infuse it with music. Music is all about emotions, and emotions are all about memories.

Thaut goes on to suggest that positive moods help us form and retain memories better, and that musical memories have a powerful ability to trigger non-musical memories attached to the music (2005, 76). Marilyn Boltz and others have demonstrated this very effect in the ability of positive music (inciting feelings of lightheartedness, gaiety, relaxation) to enhance the ability of audience members to specifically recall scenes underscored by positive music as compared to scenes in which there was no underscoring at all, or even negative music (inciting feelings of anger, apprehension, melancholy) (Boltz, Schulkind and Kantra 1991, 603). However, episodes involving the emotion of fear appear to have a prominence all their own, and as LeDoux and others have reported in their studies, fear responses appear to get indelibly etched into our brains—the more traumatic, the more indelibly etched (LeDoux, Romanski and Xagorais 1989, 238). Cue the tense underscore leading up to the startle effect in the horror movie scene.

Our brain’s emotional connection to memory is so critical that we have developed an organ in the oldest part of our brain largely devoted to processing emotional memories: our old friend the amygdala (see Figure 2.14). The amygdala sits adjacent to the hippocampus, and Daniel Levitin’s research has consistently shown that the amygdala responds to music but not to random collections of sounds or musical tones (Levitin 2007, 167). What’s more, remember that the path for music to our amygdala short-circuits the auditory cortex and the more consciously analytical centers of our brain in the neocortex. Our ears connect directly from the thalamus area to the amygdala in the subcortical structures of our brain (LeDoux, Romanski and Xagorais 1989, 238). We don’t even get a chance to think about how we react before the music already stimulates our emotional memories! It’s no wonder then that music is such a powerful conditioning influence to help etch elements of the story in our brains.

Marilyn Boltz and her team have also demonstrated that there are two important conditions in which we can use music to increase the ability of the audience to recall a scene. The first they call Congruency Accompanying Music. Music that incites the same emotional reactions as the ideas of the scene is more likely to increase the ability of the audience to remember the scene; sad music accompanies the death scene, and romantic music accompanies the love scene. Curiously, if the emotional content of the music scoring a scene does not match the emotions of the scene, the audience will still remember the scene better with music, as long as it is positive music scoring a scene with negative emotions (1991, 598). For example, I’ve done two productions of Shakespeare’s Twelfth Night, one with my old friend Joel Fink at the Colorado Shakespeare Festival, and the other with my old friend Jim O’Connor at Purdue. In Act IV, Scene 2, Feste visits Malvolio in prison and promises to help him. Feste leaves and sings the song, “I Am Gone Sir.” In the Colorado production, I wrote a sad accompaniment congruent to the general scene. However, in the Purdue production, I used the same melody, but contrasted the melancholy of the scene with an almost circus themed orchestration (happy).13 Boltz and her team refer to this special case as Ironic Contrast (1991, 602). Curiously Boltz and others report that reversing this technique, that is, using sad underscore in a happy scene, does nothing to increase our ability to remember the scene. And, to be sure, I cannot remember any instances in my own work using this technique!

Boltz’s second condition involves foreshadowing music. We use foreshadowing music at some point before a scene to create an emotional expectation of what is to come. Foreshadowing, it turns out, creates more memorable moments if the music creates an expectation that is not fulfilled by the dramatic moment the audience presumes the music to foreshadow (1991, 601). For example, director Joel Fink set our Chicago production of Shakespeare’s Henry V in England during World War II, creating a natural resonance for Henry’s triumph at Harfleur against the Normandy invasion. We ended with a symphonic orchestra playing the British national anthem (“God Save the Queen”), creating the expectation of a triumphant ending. Just as the theme climaxed, however, we punctuated the moment with the sound of the atomic bomb exploding over Hiroshima, a grim foreshadowing of the horror of war that followed both Henry V and World War II, hopefully made more memorable by the triumphant music that set up one of the more incongruent events in human history.

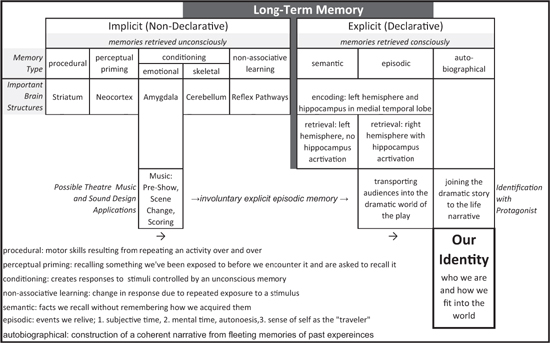

Once we have created a strong memory by attaching a dramatic moment to an emotionally strong musical stimulus, we are then free to chunk it and important elements of the play into a larger more significant experience by inducing the audience to recall it—either unconsciously without the audience bringing the memory to mind, or consciously, in which we attempt to bring a previous dramatic moment back into the working memory of each audience member. These two general types of long-term memories are called implicit and explicit.14 Implicit memories are memories you have that you don’t even consciously think about when you use them, the classic example being tying your shoelaces. You’ve done it so many times that you can do it without even thinking about it. Explicit memories are the ones you consciously think about, like remembering where you put your shoes in the first place (“I know I had them on when I came into the house”). Both of these types of memories can be activated simultaneously. Consider playing the piano. We practice scales for hours every day until we form what my piano teacher, Caryl Matthews, used to call muscle memory. That’s implicit, we don’t even have to think about how to play anymore, it just happens. At the same time, we may have to remember how that tune went either by remembering what was on our cheat sheet, or just by knowing the rules for that kind of tune, and thinking about all the other chord progressions that went like that. That’s explicit memory. We’ll consider both implicit and explicit memories, one at a time.

Implicit Memory

Morris Muscovitch and others describe three different types of implicit or non-declarative memory: perceptual priming, procedural, and conditioning. Perceptual priming refers to our perceiving something (such as a picture or a face) more quickly if we have been exposed to it (primed) before we see it again and are asked to recall it—even if we don’t remember having ever seen it before. Procedural memory involves motor skills such as riding a bicycle that we learn as a result of repeating an activity over and over—even if we have no memory of the learning or repetitions. Conditioning is a type of learning that creates responses to something that is controlled by an unconscious memory, for example if I start feeling anxious around dogs because I was bitten by one as a child (I was, but I’m not). Researchers believe that implicit memories form in the areas of the brain where they are first perceived, for example, in the basal ganglia for motor skills such as playing that piano, or in the posterior neocortex (where we process vision) for visually induced memories such as seeing the picture or face (Moscovitch et al. 2005, 38–39). Larry Squire added the cerebellum and various reflex pathways (e.g., nerve responses in the spinal cord) to Moscovitch’s list, as well as our old friend the amygdala, which can “modulate” the strength of just about any memory based on its emotional characteristics (Squire 2004, 173).

Merlin Donald suggested that the ability to voluntarily recall memories, a distinctive ability that separates humans from other animals, first appeared as an evolutionary adaptation in procedural memory. Such an adaptation allowed humans to systematically rehearse and recall memories in a manner that would lead to mimesis, the systematic ability to “initiate a specific pattern of learned action, review it, and then repeat it, or modify it, to improve performance.” Early humans were able to consciously observe themselves, and critically review their actions, what Merlin refers to as the “review-rehearsal loop.” The evolution of this “review-rehearsal loop” led directly to mimesis, pantomime, and eventually public performances and theatre (2012, 276–278). Donald insists that “mimesis and language were both impossible without voluntary recall from procedural memory” (2012, 282).

It probably doesn’t seem like all this could have much to do with creating sound scores, but consider how we condition our audience using music and sound. Of course, we have already talked about how we use preshow music to “get the audience in the mood,” or to condition them to enjoy the performance. We often do more—a lot more. Consider the old hero, heroine and villain themes from the old melodramas. The “Mysterioso Pizzicato” has been used so often to condition the audience about the villain being up to no good that it has become a cliché. Daniel Schacter, one of the earliest researchers of implicit memory, cites studies that demonstrate that a subject’s attitude toward another person can be unconsciously influenced by exposure to hostile stimuli of which the subject is unaware (1987, 511). And, quite frankly, we do it all the time in scoring by using music to which we do not intend the audience to consciously attend, but nevertheless incite emotions in them that shape their impressions of the character.

We do this so much, however, that, like the villain’s theme, character themes have become something of a cliché themselves. I remember having a conversation with my friend Tom Mardikes, an outstanding sound designer who succeeded me as the chair of the USITT Sound Commission in 1998. We were having coffee and I mentioned a student composer I was mentoring and the character themes he had developed for a show. “If I ever hear a character theme again, it will be too soon,” Tom commented. I don’t think I’ve used a character theme since.

The intent of the character theme is to influence the audience more or less subconsciously. The reality is that we often hit them over the head with our heavy-handedness, while everyone insists that the effect is subliminal. The problem, of course, is that character themes are often inherently one-dimensional, and the conflicts of our characters are (hopefully) multidimensional. We hope to use underscoring to incite a whole range of moods and emotions, in various combinations at various moments in the journey of the play. We try to attach these to multiple essential ideas related to (typically) the essential journey of the characters in the play. A simplistic strategy of “one size fits all” rarely seems to work.

Now, I tend to be much more selective about how I work to condition the audience toward the play by attaching important ideas of the play to a range and combination of emotions incited by the music. I do this rather than simply create a composite, individual character theme, which tends to oversimplify the complex emotions experienced by an individual character in a play, and the complex ways in which they might interact with the major ideas of the play. Typically, I might start by creating a number of chunks of music that incite a variety of the complex emotions we encounter in the play. I do this early on in the process, after I have chosen my color palette, but before we have spotted the cues in the script if at all possible. Sometimes I’ll just write a “suite” of music that seems to generally trace the emotional journey of the play, knowing that I’ll be able to later break the piece apart and use individual sections for specific cueing. This gives us a number of pieces that are very much “plug and play” for particular moods and moments. But it also gives us a number of related themes that get us in the ballpark, allowing us to quickly reshape each theme toward the given moment. For me, this approach seems to allow a more organic approach to tracing important ideas that surface in the course of the play.

A similar approach is to create a number of chunks using the color palette one has chosen for the play, and derived from the main motifs we have chosen to wrangle ourselves into a specific style. Composers who must work quick in rehearsals often use this technique so that they can quickly adapt a piece of music to a specific scene right in the middle of a technical rehearsal. When we created the music for the Indianapolis 500 productions, the producers had no idea what would happen down the road. They asked us to just provide them with as many different chunks as possible, from slow and reflective to fast and furious. Then the unimaginable happened. During one of the practice laps, a car crashed in turn one, killing the driver. My collaborator Michael Cunningham had an idea while we were creating chunks to create a slow dirge-like piece based on the ticking sound of a wheel slowly turning. I never imagined it would find a use in the fast-paced action of Indy car racing. The producers wound up using that piece under the footage of the crash in the daily show, Road to Indy. To this day, I cannot think of a more haunting moment of sound score composition in which I have been involved.

Inasmuch as we are able to subtly persuade our audience’s impression of a character or idea, we should realize that with such a power comes responsibility. An important phenomenon we share with politicians when manipulating audiences is known as the Illusion of Truth. For many years, researchers have known that simply being familiar with a statement increases the chances that the audience will label the statement as true. Ian Maynard Begg and his collaborators trace discussion of the phenomenon back to Wittgenstein, who famously remarked that believing statements simply because they were repeated is like buying another copy of a newspaper to see if the first one is right15 (Begg, Anas and Farinacci 1992, 446).

My friend Carrie Newcomer noticed a rather odd phenomenon as she toured her music through Germany in 2015. There was this strange fascination with folk music—Irish, American, Eastern European, just about any kind of folk music except … German folk music. Finally, she asked her hosts why the Germans didn’t seem to embrace their own folk music. It turns out that the Nazis co-opted their nationalistic music from traditional German folk songs, reusing those songs to score the agenda of the Nazi party. The Nazi party knew what every religion, government and sports team has always known: the value of repetition in music and lyrics to make the cause at hand feel more true. And, in the right cause, the repetition of a musical theme can be a very powerful thing. I still get a tear in my eye when I sing the national anthem at the football game, remembering my father who sacrificed a great part of his life for our cause. But, as sound designers, we should also be careful, or at least cognizant about using such a power capriciously, adding validity to characters and causes we know to not be true.

Explicit Episodic Memory

We’d like to think that all of our underscoring goes unnoticed, and manipulates the heck out of our audiences, but the plain fact of the matter is that the audience is free to listen to anything they like in the theatre, and will undoubtedly be aware of the music score. Jack Smalley, who teaches film scoring at the University of Southern California and has scored many major movies, television series and cartoons, describes the idea that “the audience should not be aware that there is music” as “nonsense”16 (Smalley 2005). I have already suggested that starting a sound cue in the middle of dialogue is asking for trouble, as audience attention will be drawn to the change in the auditory environment (the music), and may miss important dialogue. We already know that audience attention shifts in and out of the sound score, and we are hopefully going to work hard to shape the when and where of those shifts. When the sound score or its triggers become conscious, we open additional opportunities to manipulate explicit or declarative memory to enrich the dramatic experience.

Squire suggests that declarative (explicit) memory is the kind of memory we most often think about when we use the term “memory” in everyday language. It’s all about the things we can consciously remember, and it comes in two basic flavors, semantic and episodic. Semantic memories are simply the facts we remember about the world, without memory for how, where or when we acquired the facts. For example, I know that a mile is 5,280 feet, but I’ll be darned if I can remember the specific moment I learned that helpful tidbit. When we encode episodic memories, we not only memorize the raw facts, but we remember the whole experience, as if we were there again (Squire 2004, 173–174). We re-live the memory, mentally traveling back in time to it.

There are a couple of extraordinary biological differences between recalling semantic memories and episodic memories. Both semantic and episodic memories use cortical structures in the left hemisphere of the brain to encode memories. However, episodic memory retrieval activates the right hemisphere almost exclusively, while semantic memory retrieval activates the left hemisphere almost exclusively. Both types of memory require the hippocampus in the medial temporal lobe to encode the memories. However, once those semantic memories become embedded in our long-term memory, the hippocampus no longer activates when we recall them (Moscovitch et al. 2005, 39–40; Tulving 2002, 17–18). In contrast, activating episodic memories of our past life seems to always require activation of the hippocampus. If our hippocampus gets damaged, we can remember old facts, no problem, but we lose our ability to travel back in time and relive the experience (Moscovitch et al. 2005, 35, 52, 54, 59).

As lovely and important as semantic memory is—in truth it would be so hard to understand a play without it—it’s our ability to manipulate consciousness around episodic memory that provides the most intriguing opportunities for this composer and sound designer. In a way, I tend to think about music being more related to episodic (both somewhat right-brained) and idea being more related to semantic (somewhat left-brained) in our equation of song = music + idea. Let’s spend a little extra time considering some of the nuances of our episodic memories.

Endel Tulving first introduced the concept of episodic memory in 1972. He points to a couple of important characteristics that we have explored very early in this book. The first is the malleable concept of time that we discovered in Chapter 3 was inherently subjective and unique to each individual. Humans appear to be the only animals capable of perceiving anything other than the present time.17 Other animal species appear to be unaware that their perception of time is hopelessly biased by their own subjective point of view. But it’s Tulving’s other major concept we raised earlier that really addresses another consideration of human consciousness: not only are we aware of the past and the future, but we have the ability to mentally travel into them, an ability Tulving describes as autonoetic consciousness.18 Autonoetic consciousness is a special kind of consciousness in which we mentally travel back in time, but retain awareness that our physical selves have not “left the building,” so to speak. Tulving called this uniquely human ability “mental time-travel.” Tulving combined his conceptions of the subjective perception of time and autonoetic awareness with a third characteristic, the somewhat unique human sense of self, which Tulving called the “traveler,” to describe three essential characteristics of episodic memories (2002, 1–3).

Here we have another model of human consciousness that closely resembles our special type of consciousness when we experience theatre. Tulving’s model for episodic memory also resembles dreaming as we discussed in Chapter 3, except that in the “daydreams” of episodic memory, we maintain some awareness of our waking world. Tulving’s description of episodic memory also bears a close resemblance to the shaman’s altered state of consciousness that we described in Chapter 9, except that we relive our own experiences in these memory episodes, not the imagined experiences induced by the shaman’s story. Our conscious experience in theatre also resembles both of these experiences, so we should not be surprised to find that episodic memory is closely related to how we experience theatre. Theatre artists create dramatic scenes that the collective audience experiences as if they were time-traveling into them—with varying degrees of autonoetic consciousness. At the same time, theatre artists have an opportunity to incite each member to mentally time-travel into their own unique episodic memories. It is the opportunity to connect the “collective dreaming” of the mise-en-scène with the unique “mental time-travel” of each audience member that gives theatre its extraordinary power.

In our particular case, we want to know how can we use music to enhance the collective dreaming of the entire audience, and cue each individual’s mental time-travel. One key is using thematic sound, sound that recurs to first incite the audience to collectively experience the drama as if it were happening to them, and then to incite the audience to re-experience those same memories in the course of the story as episodic memories within the realm of the story. We stimulate a cohesive collective experience by inciting the audience to involuntarily recall prior dramatic moments in the story, creating what we refer to as involuntary explicit episodic memories. When we stimulate mental time-travel in each unique audience member by causing each audience member to re-experience prior events in their own life, and associate that with specific moments in the play, we create what we call autobiographical memories. We’ll explore both involuntary explicit episodic memories and autobiographical memories in the next two sections.

Involuntary Explicit Episodic Memory

In the section on working memory, we described the process of using our sound scores to chunk individual dramatic moments into a larger outline of the story that makes it easier to hold the whole story in our conscious memory. Chunking the story, then, works in the same way as chunking our memories in real life: it allows us to fully engage in the moment, while bringing to mind only the memories that have the most critical bearing on the moment. As we discussed about the nature of entrainment in Chapter 6, our sound scores work primarily in the realm of experience—they don’t use up any of the “seven +/− two” items in our working memory like symbols, signs and indexes do. Any use we make of music in our plays helps to create the time-travel experience. Associating the present moment with our chunked memories of prior dramatic moments not only helps to keep the whole story in our conscious minds, but also uses up the seven +/− two items we can consciously hold in our working memories at once. When our working memory fills up, we are, for all practical purposes, fully immersed in the dramatic story, fully time-traveled into the world of the play.

There may be moments in the script where we consciously ask the audience to retrieve prior memories in the play (Hamlet’s ghost: “Do not forget: this visitation is but to whet thy almost blunted purpose”). With the sound score, however, we have an opportunity to plant the cues for recalling prior dramatic moments within the sound score, inciting the audience to involuntarily recall relevant chunks at the appropriate present moment in the play. A memory evoked by specific cues from an individual’s past experiences is called an Involuntary Explicit Episodic Memory. Involuntary, because we don’t use the executive functions of the right prefrontal cortex to make an effort to consciously recall the memory,19 but we do otherwise use the same areas of our brain as in voluntary episodic memory recall (Hall, Gjedde and Kupers 2007, 262, 267; Berntsen 2012, 296). Explicit, because the memory enters our consciousness; and episodic, because we don’t just remember the memory, we mentally “time-travel” back into it.