INFLATIONARY SALARY MECHANISMS

DO FIRMS HAVE SHORT MEMORIES?: EVIDENCE FROM MAJOR LEAGUE BASEBALL

Andrew Healy

A growing, and now large, body of evidence indicates that economic agents often do not conform to the classical rational model of behavior. In many cases, bounded rationality better describes behavior (Kahneman, 2003; Simon, 1957). Rather than carefully considering all available information, agents often rely on rules of thumb to solve problems, particularly when those problems are complex (Tversky & Kahneman, 1974). One rule of thumb that may cause significant inefficiencies involves limited memory. Psychological research shows that people tend to primarily remember only salient events (Thompson, Reyes, & Bower, 1979). If economic agents forget or ignore less salient information, they will fail to act optimally when making decisions that could be improved by that information. This article shows that these limits to memory lead firms to make systematic mistakes in their salary offers.

Because performance and pay are easily measured, the market for baseball players offers an ideal laboratory for testing theories about compensation (Kahn, 1993; Sommers & Quinton, 1982), including theories relating to the effect of limited memory on salary offers. Also because salaries are so high, the costs of any mistakes are amplified. The presence of inefficient behavior in the market for baseball players would likely extend to other environments where the stakes are lower. The data show that teams are susceptible to a specific kind of inefficient behavior. Teams reward players for performing well in the immediate past, ignoring other evidence of a player’s quality from his earlier performance. When choosing salary offers, teams have short memories.

This finding will likely not surprise baseball fans. Many anecdotes suggest that players often receive excessively lucrative contracts after one anomalous good season. For example, Adrian Beltre, a third baseman for the Los Angeles Dodgers, had an exceptional season in 2004. After the 2004 season, despite the absence of any similar success in the preceding years, the Seattle Mariners offered Beltre a 5-year $64 million contract. The contract paid Beltre as if he would continue to perform at his 2004 level, but he has instead reverted to his pre-2004 form.1 Although other anecdotes also suggest that players are excessively rewarded for performing well in the final years of their contracts, testing the hypothesis that teams have short memories requires a comprehensive analysis of players’ salaries.

In this article, I analyze salary and performance data for all major league baseball hitters who signed free agent contracts from 1985 to 2004. The data show that a player’s performance this year is predicted about 20% more strongly by his performances from 2 and 3 years ago than by his performance from last year by itself. In contrast, a player’s salary this year depends only half as much on his performances from 2 and 3 years ago as on his performance from last year. In other words, for determining future performance, there is more information in a player’s earlier performance history than in his performance last year alone. Salaries, however, respond much more strongly to performance in that most recent year than to the earlier performance history.

Teams are not equally prone to underweighing earlier performance relative to recent performance. Controlling for total payroll, the teams that win the most games use past performance data most effectively. Only the unsuccessful teams put significantly too much weight on recent performance relative to earlier performance. One plausible explanation for this result is that well-managed teams are less susceptible to making memory-based mistakes in their salary offers.

What could cause memory-based biases to affect baseball salaries? Previous research in the psychology of memory offers a compelling explanation. People often access the most salient memories when making decisions. Reacting primarily to salient memories in this way corresponds to the availability heuristic (Kahneman & Tversky, 1973; Mullainathan, 2002). The most salient memory about a player who just had a remarkable season may be his recent outstanding play, whereas other relevant performance data fail to stand out as much. Availability could have caused the Seattle Mariners, for example, to believe that Adrian Beltre’s lone exceptional season more accurately described the player’s skills than his previous years of unexceptional play.2 In general, this sort of behavior could explain why teams fail to take into account a player’s performance in earlier years when making a salary offer.

….

ESTIMATION STRATEGY

As in previous research using baseball data, I focus on a player’s contribution toward winning games, through which the player affects a team’s revenues (Quirk & Fort, 1992; Scully, 1974; Sommers & Quinton, 1982). The previous research indicates that, to maximize revenues, a team primarily needs to focus on winning games. To the extent that other factors influence salary offers, the estimation strategy only requires that those other factors are not related to changes in a player’s performance history over time.

In this article, I will focus entirely on hitters. A variety of measures captures different aspects of a hitter’s value to his team. The number of homeruns that a player hits, a player’s on-base percentage, and his slugging percentage are three such measures. Previous research suggests that a measure called OPS, the sum of on-base percentage and slugging percentage, is the best single measure of a player’s offensive value (Albert & Bennett, 2001). In this article, I use OPS to measure a player’s worth.

….

THE DATA

To test hypotheses relating to how effectively teams use past performance data to make salary offers, I use data on free agent signings in major league baseball from 1985 to 2004. The term free agent refers to a player whose contract has expired and who is free to negotiate with all teams except his original team. The competition for highly valued free agents can be fierce.3

For the analysis, I focus on free agent signings that occur between October and April, when regular-season games are not taking place and the vast majority of free agent signings occur. Focusing on off-season signings allows for a clear comparison between a player’s performance before and after the contract is signed. Of those signings, the regressions in this study are based on all observations for which players have at least 200 at-bats in the previous two or three seasons.4 By using this sample, I analyze the performance and salary data for all players who have played a significant amount of time in each of the 3 years preceding the signing of the free agent contract.

The data on players’ salaries and past performances are obtained from The Baseball Archive.5 The past performance data include measures of every standard statistic for each player. I construct a player’s OPS by adding his on-base percentage and slugging percentage. The salary information refers to a player’s base salary for the given years. To determine free agent signings, I use the data on baseball transactions compiled by Retrosheet (2006). These data contain information on all free agent signings that occur from 1985 to 2004.

The data show that the average salary has increased from $500,000 in 1985 to $2.8 million in 2004. Baseball salaries are also highly skewed and have become more skewed over time. The median baseball salaries in 1985 and 2004 were $410,000 and $870,000, respectively….

RESULTS

In this section, I estimate how a player’s performance history affects current performance and salary. The data show that past performance predicts current performance and salary in strikingly different ways. In addition, the data show that these differences and the inefficiencies they imply do not occur for the teams that are generally managed more effectively.

Testing for Short Memories

… [A] player’s performance is predicted only slightly more effectively by last year’s performance than by his performance from 2 years ago…. On the other hand, an increase in last year’s performance is about twice as effective at increasing that player’s salary as is an increase in performance from 2 years ago….

Although teams could do somewhat better by assigning more weight to performance data from 2 years ago, they are even more ineffective at using earlier performance data….

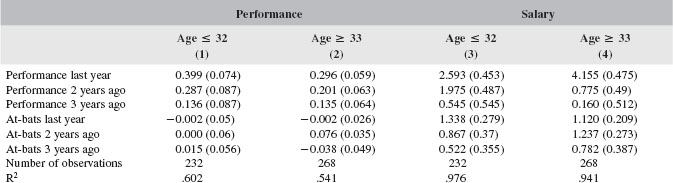

Teams’ incorrect weighting of previous performance information occurs primarily for older players, as shown in Table 7. Comparing players who are 32 and younger to those who are 33 and older breaks the data roughly in half. Relative to last year’s performance, earlier performances predict current performance about equally well for older and younger players. To some extent, all previous performances (last year and earlier) predict current performance less well for older players. The stark difference between older and younger players, however, occurs for salary. For younger players, performance last year predicts salary about 1.5 times more strongly than performance from 2 years ago. For older players, this ratio is more than 4. Teams appear to have particularly short memories for older players. Teams pay older players almost entirely based on their performance in the previous season, and the data show that, by doing so, they make significant mistakes in their salary offers.

Testing for Optimal Use of Previous Performance Data

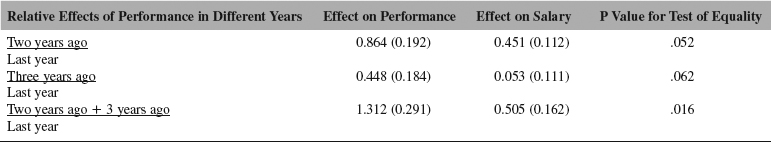

…. If teams use past performance data in an optimal way, they will use past performance data to determine salary offers in the same way that those performances affect current performance…. For example, for current performance, the predictive power of performance from 2 years ago is about 0.864 times as large as performance from last year. For salary, the predictive power of performance from 2 years ago relative is about 0.451 times as large as performance from last year…. In predicting current performance, the effect of performance from 3 years ago is about 0.448 times the effect of performance from last year. The estimated effect of performance from 3 years ago on salary is only 0.053 times the effect of last year’s performance….

Taken together, the effects of all three earlier years on performance and salary indicate the significant gap between how teams actually use past performance data and how they would optimally use that information. For current performance, the predictive power of performance from 2 and 3 years ago is about 1.312 times larger than performance from last year. For salary, the predictive power of performance from 2 and 3 years ago is only 0.505 times the performance from last year. The difference between these two ratios is significant (p = .016). If the goal is to predict how well a player will perform, there is more combined information in that player’s performances from 2 and 3 years ago than in his performance from last year by itself. Nevertheless, teams put about twice as much weight on last year’s performance as on a player’s performance from 2 and 3 years ago. The data thus reject the hypothesis that teams correctly use players’ past performance histories to determine their salary offers.

Table 7 Comparing Across Age Groups

Source: Journal of Sports Economics. Used with permission.

Successful and Unsuccessful Teams

… I plot average wins against a team’s average payroll relative to the other major league baseball teams from 1985 to 2004. To calculate relative payroll in a season, I divide each team’s total payroll in a season by the mean payroll for all teams. Then, I take the mean relative payroll for each team across seasons…. In the discussion below, I refer to the teams that have achieved more wins than their payrolls would predict as successful teams. I refer to the teams that have achieved fewer wins than their payrolls would predict as unsuccessful teams.

By the standard of getting the most wins out of the salaries it has paid, Oakland has been the most successful team in baseball. Oakland averaged 86 wins per season from 1985 to 2004, even though its average payroll during that time predicts only 79 wins. On the other end, Tampa Bay was the least successful team, averaging only 65 wins from 1998 to 2004, 10 fewer wins than the 75 wins that its average payroll predicts.8 …

This classification makes it possible to test for differences in how successful teams use past performance information compared with how unsuccessful teams use that information….

… [S]uccessful teams do a better job of making their salary offers match up with how past performance data predict players’ present performances.9 This result comes from two different sources. (See Table 8.) First, compared with unsuccessful teams, successful teams put higher relative weight on performances from 2 and 3 years ago when determining their salary offers. Second, successful teams sign players whose current performance is better predicted by last year’s performance. In other words, successful teams base their salary offers more on earlier performances than unsuccessful teams and, to the extent that successful teams sign players who performed well in the most recent year, those teams pick players for whom that recent success actually does foretell future success.

… One possible explanation for these differences in the types of players that successful and unsuccessful teams sign is that unsuccessful teams are more susceptible to over-paying players who have good statistics in the most recent season because of luck. To illustrate this idea, consider the example of Adrian Beltre, the player who signed a lucrative contract after one anomalous excellent season and then did not perform as well in the following season. If unsuccessful teams are particularly prone to signing players after one anomalous good season, then the players that these teams sign will have their performances better predicted by earlier years than players signed by successful teams.

… [O]nly the unsuccessful teams show significant memory-based biases in their salary offers. The successful teams treat past performance data similar to how they optimally would….

In contrast, the unsuccessful teams use past performance data to determine salaries in a significantly different way than that information predicts future performance…. Relative to last year’s performance, a player’s earlier performances from 2 and 3 years ago predict current performance almost 4 times more effectively than it predicts that player’s salary. No such difference is present for the successful teams.

CONCLUSION

To best use the dollars that they spend on salaries, organizations need to predict how well players will perform in the future. The data show that organizations make systematic mistakes in how they make these predictions. Teams infer too much from players’ performances in the most recent season relative to performances from earlier years. The organizations that make these mistakes are the same ones that generally fail to spend their resources well. Organizations that are otherwise more successful also use past performance data more effectively. The sizeable mistakes that unsuccessful teams make could arise from two different hypotheses about player behavior in the final year of a contract. First, it may be the case that players are rewarded for good luck in the last season of their contract, as previous research has demonstrated that CEOs are rewarded for luck (Bertrand & Mullainathan, 2001). In support of this hypothesis, Albert and Bennett (2001) show that a player’s performance in any given year reflects a great deal of luck. On the other hand, there may be certain players who exert greater effort in the final years of their contracts and certain teams repeatedly fail to recognize this behavior. The tendency shown in this article for teams to excessively reward performance at the end of a contract would amplify a player’s incentive to try harder in his contract year. Future research could attempt to determine whether teams are rewarding players for luck in the final years of their contracts or for extra effort that they exerted in their contract years.

….

Table 8 Last Year’s Effect Compared with Earlier Years

Source: Journal of Sports Economics. Used with permission.

1. Statisticians often use on-base plus slugging percentage (OPS) to measure a hitter’s performance (Albert & Bennett, 2001). From 1999 to 2003, Beltre averaged a 0.756 OPS with a highest value of 0.835 in 2000. Then in 2004, his OPS jumped to 1.017. In the two seasons since, Beltre had a 0.716 and 0.793 OPS, respectively.

2. A related phenomenon, the “hot hand,’’ can also be understood by invoking the availability heuristic as it applies to memory. Camerer (1989), for example, found that bettors incorrectly believe that a basketball team that has had recent success will also have future success. Likewise, Gray and Gray (1997) found that odds for football games are skewed toward teams that have had recent success. They find that bettors’ behavior “is consistent with the idea that the market overreacts to recent form, discounting the performance of the team over the season as a whole.’’

3. Baseball players gained the right to free agency in 1976. Even though owners of baseball teams have been found guilty of colluding to keep players’ salaries down as recently as the early 1990s, there is sufficient competition in the market for baseball players that experienced players have been receiving approximately marginal product wages going back to at least 1986 (MacDonald & Reynolds, 1994).

4. Using other at-bat thresholds, such as 150 or 300 at-bats has no effect on the general results.

5. I thank Sean Lahman of The Baseball Archive (2006) for help in accessing these data.

….

8. Tampa Bay entered major league baseball as an expansion team in 1998.

9. In addition, the R2 for the salary regressions is larger for the successful teams than for the unsuccessful teams, indicating that there is less unexplained variation in the salary offers made by successful teams.

References

Albert, J., & Bennett, J. (2001). Curve ball: Baseball, statistics and the role of chance in the game. New York: Springer.

Bertrand, M., & Mullainathan, S. (2001). Are CEOs rewarded for luck? The ones without principals are. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 116, 901–932.

Camerer, C. (1989). Does the basketball market believe in the “hot hand’’? American Economic Review, 79, 1257–1261.

Gray, P., & Gray, S. (1997). Testing market efficiency: Evidence from the NFL sports betting market. Journal of Finance, 52, 1725–1737.

Kahn, L. (1993). Free agency, long-term contracts and compensation in major league baseball: Estimates from panel data. Review of Economics and Statistics, 75, 157–164.

Kahneman, D. (2003). Maps of bounded rationality: Psychology for behavioral economics. American Economic Review, 93, 1449–1475.

Kahneman, D., & Tversky, A. (1973). Availability: A heuristic for judging frequency and probability. Cognitive Psychology, 4, 207–232.

Lahman, S. (2006). The baseball archive. Retrieved August 20, 2006, from http://www.baseball1.co.

MacDonald, D. N., & Reynolds, M. O. (1994). Are baseball players paid their marginal products? Managerial and Decision Economics, 15, 443–457.

Mullainathan, S. (2002). A memory-based model of bounded rationality. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 117, 735–774.

Quirk, J., & Fort, R. (1992). Pay dirt: The business of professional team sports. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Retrosheet (2006). Transactions. Retrieved August 20, 2006, from http://www.retrosheet.or.

Scully, G. (1974). Pay and performance in major league baseball. American Economic Review, 64, 915–930.

Simon, H. A. (1957). A behavioral model of rational choice. In Models of man: Social and rational; mathematical essays on rational human behavior in a social setting. New York: Wiley.

Sommers, P., & Quinton, N. (1982). Pay and performance in major league baseball: The case of the first family of free agents. Journal of Human Resources, 17, 426–436.

Thompson, W.C., Reyes, R. M., & Bower, G. H. (1979). Delayed effects of availability on judgment. Unpublished manuscript, Stanford University.

Tversky, A., & Kahneman, D. (1974). Judgment under uncertainty: Heuristics and biases. Science, 185, 1124–1131.

THE NATIONAL HOCKEY LEAGUE AND SALARY ARBITRATION: TIME FOR A LINE CHANGE

Stephen M. Yoost

I. INTRODUCTION

… On February 16, 2005 the National Hockey League (NHL or League) became the first professional sports league in North America to ever cancel an entire season on account of a labor dispute.3 Three-hundred and one icy days of bitter conflict-the longest labor dispute in North American professional sports history-finally ended on July 13, 2005 with a new collective bargaining agreement (CBA) between NHL players and owners.4 Much of the excitement surrounding the end of the lockout focused on the League’s new rules of play, which the owners hope will promote scoring, speed, and excitement in the game.5 In an effort to put the 2004–05 lockout firmly in the League’s past, the NHL also unveiled a new logo.6

While an offense-friendly rulebook and a fresh look will help bring back some excitement to a League that has lost its luster, low-scoring games and a logo reminiscent of the 1970s did not cause the NHL’s labor lockout or its financial woes.7 Although the NHL has traditionally enjoyed its status as one of North America’s four major professional sports leagues,8 the NHL has recently been in serious danger of losing its prominence among sports fanatics throughout the United States and even in Canada.9 With player salaries soaring10 and big-time television contracts falling,* the NHL has turned off much of its fan base.12 The League’s operating costs have reached an all-time high,13 and fan interest has sunk to an unprecedented low.14 The business model of the NHL’s old collective bargaining agreement led to this financial disarray and the labor lockout of 2004–05.15 In an effort to ameliorate the League’s fiscal crisis and prevent another labor dispute, the League’s new CBA includes some necessary changes to its plan of business.16

Salary arbitration was a key element of the NHL’s old collective bargaining agreement with its players, and it remains the cornerstone of the League’s settlement of salary disputes under the new CBA.

….

II. THE FINANCIAL DECLINE OF THE NATIONAL HOCKEY LEAGUE

The NHL hopes the new CBA will stop the League’s serious financial decline that occurred over the life of the last collective bargaining agreement.30 Following the 2002–03 season, nineteen of the NHL’s thirty teams reported an operating loss.31 Those nineteen teams lost a combined $342.4 million in that one season alone.† Four teams lost over $30 million, only one team lost less than $5 million, and the remaining fourteen clubs lost between $5 million and $30 million.33 The average loss of these nineteen franchises was $18 million.34 In addition, four teams have gone bankrupt.35

The few profitable teams do not sufficiently counter the failing teams: of the eleven teams that reported a net profit for the 2002–03 season, only two clubs produced over $10 million.36 The average profit of these eleven clubs was a meager $6.4 million, and their combined profit was just under $70 million.37 As a result of these figures, the NHL as a whole lost around $273 million during the 2002–03 season.38 The NHL’s dire financial situation has prompted the League’s commissioner to admit that “we lose less money by not playing.”39

These figures beg the following question: why did the NHL lose so much money? Several factors, including an overall decreasing fan interest40 and rapid expansion to relatively uninterested markets, contributed to the problem.41 In the decisive Game Seven of the Stanley Cup Finals in June 2004,42 ABC registered a 5.4 viewer rating, which was 0.4 lower than the previous season’s Game Seven rating.43 Earlier games in the 2004 Stanley Cup finals attracted the lowest ratings in twenty years.44 The 2004 World Series of Poker attracted higher ratings on ESPN, a national cable network, than the first two games of the Stanley Cup Finals on ABC, a national network with a greater potential audience than ESPN.45 Reflecting the reality that hardly anybody watches the NHL on television anymore, NBC paid the NHL no money upfront in the League’s latest TV deal.46 The NHL hopes that the newly unveiled rules of play for the 2005–06 season will help spark fan interest and reverse these recent trends.47

Between 1991 and 2001, the NHL added nine new franchises.48 In addition, the League placed some of these teams in warm places where one would not expect to see ice hockey.49 At the same time, traditional hockey towns like Winnipeg and Quebec, Canada lost their teams to less-interested American markets.50 This expansion to weak markets, coupled with a decreasing fan base, helped to create the NHL’s financial difficulties.

While the NHL’s poor business decisions helped run the League into the ground, out-of-control player salaries have played the largest part in creating the NHL’s money problems.51 The NHL’s 2002–03 audit revealed that the League spent only thirty-nine percent, or roughly $775 million, of its total operating costs on expenses other than players’ salaries.52 The NHL spent about seventy-five percent, or roughly $1.5 billion, of its revenues on players’ salaries in that same season.53 By comparison, players’ costs accounted for only about fifty-seven percent of the NHL’s revenues in 1994.54

The NHL has spent, proportionally, much more on paying its players than the other three major professional leagues.55 To amplify this financial strain, the NHL is consistently fourth in total annual revenue as well, earning about $1.1 billion less than its next closest counterpart, the National Basketball Association (NBA).56 The NHL has the dubious distinction of being the only league to have any of its franchises file for bankruptcy.57

While the NHL’s popularity has been in steady decline, players’ salaries have increased at a staggering rate. In 1994, the average NHL salary was $560,000.58 In 2004, the average salary was about $1.8 million, well over three times the average salary just ten years before.59 The League’s highest-paid players, Peter Forsberg and Jaromir Jagr, earned $11 million in 2004.60 As recently as 1996, the NHL’s highest-paid player earned half that—$5.5 million.61 These statistics readily show that, over the life of the latest collective bargaining agreement, players’ salaries have exploded and destroyed the viability of the NHL.

III. PROFESSIONAL SPORTS AND SALARY ARBITRATION

A. The Business Model of the NHL and Arbitration in General62

Disputes over labor are common, and there is no indication that this prevalence will decrease.63 There will always be disagreements in labor regarding compensation, because management and labor of any given company will disagree over how to distribute that company’s profits.64 Professional hockey is no exception to this phenomenon,65 and indeed, as long as there is big money at stake and there are even larger egos involved, professional hockey’s salary disputes will represent some of the most heated disputes in the entire field of labor.66

The National Hockey League operates like a large company with local franchises.67 The NHL is essentially a large multinational company consisting of many subparts.68 Each of the thirty teams within the NHL operates as a franchise, which means that the overall system of labor is the same throughout the League, even though different entities own each team.69 The thirty team owners collectively act as the NHL,70 agreeing to all sorts of collective business decisions.71 As franchise owners, however, the owners make team decisions for their individual franchises like local franchise owners of McDonald’s restaurants do.72 Owners decide, within the general rules of the NHL, what players to sign, how much to pay them, who coaches and manages their teams, and other important business decisions.73 This is the ownership side of the NHL’s labor system.

The players’ side of the NHL is slightly less complicated. Players negotiate and sign contracts with the teams for whom they want to play.74 Collectively, however, the players of the NHL act as the National Hockey League Players’ Association (NHLPA).75 The NHLPA is the players’ union.76 As the NHLPA, the players negotiate with the League and agree upon77 a method to govern the general labor system of professional hockey. The result of these negotiations is the collective bargaining agreement (CBA), which covers details from player eligibility to baseline compensation to training camps to salary arbitration and free agency.78 As with agreements between large companies and their labor unions, the NHL CBA periodically runs out and must be renewed by both sides for the League to continue operating.79

In the NHL, players occasionally become free agents—that is, their contracts either expire or contain provisions allowing the players to renegotiate their contracts or to offer their talents to other teams.80 Additionally, the CBA provides for salary arbitration, which gives players who meet certain criteria the opportunity to settle salary disagreements with their teams by submitting their cases to third-party arbitrators.81

Arbitration is traditionally defined as “a method of dispute resolution involving one or more neutral third parties who are usually agreed to by the disputing parties and whose decision is binding.”82 The NHL has utilized its own version of arbitration, defining those procedures in Article 12 of the old CBA.83 One of the main differences between traditionally defined arbitration and the old CBA’s version is the unique and limited “walk-away” provision, wherein one party can refuse to bind itself to the arbitrator’s decision.84

B. The Emergence of Salary Arbitration in Professional Sports

….

Salary arbitration’s roots in professional sports traces back to 1970, when the NHL first used the process to settle compensation disputes between players and teams.91 Not long after, the MLB followed the NHL’s lead by including an arbitration procedure in its 1973 CBA.92 Both leagues continue to employ salary arbitration in their respective collective bargaining agreements93 and remain the only two (of the four major professional sports) leagues to use salary arbitration.94

C. Major League Baseball’s “Final-Offer” Salary Arbitration System

Major League Baseball’s salary arbitration system is known as “final-offer” arbitration.95 When an MLB arbitration case proceeds, the player and the team’s ownership each propose a salary figure.96 Within one day of the arbitration hearing, a panel of three baseball “arbitrators must select either the player’s demand or the club’s offer.97 There can be no compromise, no explanation, and no delay.”98 Furthermore, neither the players nor the team may appeal the arbitrators’ decisions, and players may not hold out for better deals.99 The final-offer system is simple enough: for example, if the ballplayer asks for $750,000 and the owner offers $500,000, the arbitrator must choose either $750,000 or $500,000, one or the other.

The final-offer feature is designed to stimulate negotiations and to discourage arbitration.100 The final-offer system “encourages each side to put forward more realistic figures.”101 The higher chance that the arbitrator will choose the opposing side’s offer leads to this anticipated effect. In other words, if the arbitrator must choose either the player’s high demand or the club’s low offer, the parties will compromise between the two extremes rather than risk having the arbitrator rule in favor of one or the other party.102 “If either side gets too far out of line, the other’s position will be adopted by the arbitrator.”103 The desire to win the arbitration equals an incentive to be as realistic as possible, and the less extreme demand or offer typically becomes the winning position.

1. The Advantages of MLB’s Final-Offer Arbitration

There are several advantages to the MLB’s final-offer system. The final-offer approach facilitates negotiation.104 While the main advantage of settling before going to final-offer arbitration is obtaining a more favorable outcome, there are other benefits to settling salary disputes rather than going to trial or arbitration. First, arbitration hearings, like court proceedings, are adversarial and can strain the relationship between players and management.105 Second, the parties must finance their arbitrations,106 including paying the panel of arbitrators and funding their side’s costs of discovery, which yields the evidence that they submit at the hearings.107 Some elements of discovery, especially depositions, can be incredibly expensive.108 Third, when parties settle, they can devise creative multi-year deals or compensation packages that involve bonuses or no-trade clauses,109 whereas baseball’s system allows arbitrators to award only single-year contracts for specified salaries.110 Finally, settlement creates an atmosphere of cooperation, rather than of contention.111 Settlement can “build the parties’ relationship rather than rupture it”112 by allowing the players and owners to reach a mutually acceptable common ground. On the other hand, the arbitrators’ decision in an MLB salary dispute is exactly what one of the parties wanted and exactly what the other party did not want. In other words, “there is always one winner and one loser.”113 Settlement, therefore, can be superior to arbitration in many ways.

If the purpose of baseball’s final-offer arbitration system is to encourage the clubs and players to resolve their disputes without resorting to arbitration, then the MLB’s salary arbitration system operates properly when parties settle. Evidence shows that in the area of public employment labor disputes, the final-offer element encourages negotiations and settlement.114 In the Major Leagues, however, players continually resort to salary arbitration rather than settle their disputes with management, leading to speculation regarding the cause of this phenomenon.115 Disputes end up in arbitration for any of the following reasons: (1) players have “distinctly mixed profiles,” (2) one party “fails to correctly gauge the market value of a player’s services,” (3) a club may not have “the financial resources to pay” what the player demands, (4) the club may want to avoid the spiraling effects that increased compensation has on other players’ salaries, and (5) the “personalities and egos of the participants” may preclude settlement.116

When baseball players have resorted to arbitration, the owners have been more successful, at least in the relative number of times that arbitrators have picked owners’ offers.117 … While owners have won most arbitrations, the players have benefited from the MLB’s arbitration system.

2. MLB’s Salary Arbitration System’s Effect on Players’ Salaries

The salary arbitration system has led to sky-rocketing salaries in Major League Baseball.121 Even when players lose their arbitrations, their salaries tend to rise nonetheless.122 Increasing salaries result from arbitration because a player always wins his arbitration hearing, even if the arbitrators pick the owner’s offer.123 There are three ways players win salary arbitrations. First, players win arbitration by filing for arbitration in the first place.124 Simply by filing for arbitration, players consistently double their salaries.125 “Even if they never have to go through an arbitration hearing, players receive higher salaries than they otherwise would have received if they were not eligible for arbitration.”126 The reasons for this phenomenon are elusive. At least in theory, the threat of going to arbitration “tends to move both parties to negotiate in good faith.”127 Since the final-offer system encourages players and owners to settle before arbitration, perhaps the system itself, without actually using arbitration, leads to increased salaries. Additionally, owners know that arbitrators will compare their players to high-priced talent from other teams, and rather than risk losing the arbitration, owners tend to settle for a premium.128 Whatever the case, simply filing for arbitration tends to handsomely increase players’ salaries.

Second, players win arbitration by going through arbitration and losing their case.129 Like those who file and then settle before arbitration, players who lose their cases still have the market potential that comes with being a player who is eligible for salary arbitration. A player wins by losing his arbitration case, because his club must offer a reasonable market value in arbitration, and this number is always higher than what the player had previously earned.130 If this were not the case, the player would not have filed for arbitration in the first place. For example, a player who earns $500,000 the previous season demands $1.5 million dollars for next season from his team. The club offers $1 million dollars instead. If the case proceeds to arbitration, the arbitrator will award the player either $1.5 or $1 million. Either way, the player will make at least twice as much as he did the previous year.131 Studies have shown that players who “lose” their arbitrations still make an average of 150 percent their previous season’s salary.132

Third and finally, players win arbitrations by getting arbitrators to decide in their favor.133 In the previous hypothetical, if the player wins his arbitration, he earns three times what he earned during the previous season. This is a likely phenomenon, because players’ salaries have increased at an alarming rate since the MLB started using salary arbitration.134

….

While salary arbitration pushes baseball players’ salaries up and up,140 MLB management has blamed two aspects of the arbitration system for this phenomenon. For one, because arbitrators compare the player in dispute with the performances and salaries of other players in the same relative position, salary arbitration “makes one team pay for another team’s extravagance.”141 Secondly, the system does not allow arbitrators to consider teams’ market sizes, so arbitrators award players of small market teams the same salaries as their large market counterparts.142

In reality, both of these complaints revolve around baseball’s existence in large and small markets alike. Those teams that have the capacity to pay their players “extravagantly” are the same teams that operate in a “big market.”143 In the 2004 baseball season, the teams with the three highest payrolls were the New York Yankees (with a record $180 million-plus payroll), the Boston Red Sox, and the Anaheim Angels.144 New York and Anaheim have the two largest potential markets in baseball, with the New York and Los Angeles metropolitan areas topping out as the only two markets with more than ten million people.145 Along with the Big Apple and Southern California, Boston ranks among the nine markets containing five million or more people.146

No doubt these teams can afford to pay such ridiculously high salaries because they benefit from lucrative media contracts.147 … The smaller markets simply cannot match the salaries that the bigger teams lay out.152

Baseball’s salary arbitration scheme fails to take this into account.153 Arbitration relies on the salaries and statistics of all players regardless of where they play.154 The big market/small market dynamic leads to increasing player salaries across the league, at least in part due to the MLB’s salary arbitration system.

3. MLB’s Final-Offer System: Does It Work?

The crucial question about final-offer arbitration is this: does it work? That is, does the final-offer system really encourage parties to settle and to avoid actual arbitration? … Between 1990 and 2004, players filed 1469 arbitration cases and only 182 went to arbitration.157 In other words, baseball players and owners settle about ninety percent of all arbitration cases. Additionally, not all arbitration-eligible players file for arbitration,158 suggesting that the mere possibility of going to arbitration leads clubs (and players, if in their interest) to settle.159 These statistics reflect that baseball’s final-offer system decreases the number of disputes resolved by arbitration.

While the final-offer system encourages players and owners to settle instead of arbitrate, the result—increased player salaries—is the same either way. In 1974, when the MLB first relied on arbitration to settle salary disputes, the average salary in baseball was $40,839.160 Today, the average MLB salary is well over $2 million.161 While the advent of free agency no doubt played a large role in this astronomical rise,162 free agency’s coexistence with arbitration pushes baseball’s salaries up even more.163 Unrestricted free agents can seek higher salaries from other teams, and restricted free agents who qualify for salary arbitration employ the arbitration system to obtain impressive pay raises.164 As a result, Major League Baseball’s use of salary arbitration has led to a profound increase in player salaries across the league. [See Table 9 for the history of the number of cases that have proceeded to a salary arbitration hearing.]

D. The National Hockey League’s Salary Arbitration System Under the Old CBA (1995–2004)

1. The Mechanics of the NHL’s Salary Arbitration System

The MLB and the NHL are the only two of the major four professional sports leagues to have salary arbitration.165 Due to baseball’s tremendous popularity advantage over hockey166 and the MLB’s unique “final-offer” system of arbitration,167 professional baseball’s handling of salary arbitration is the benchmark from which practitioners and fans judge the NHL’s version of arbitration.168

While baseball’s arbitration system typically receives more attention than its NHL counterpart,169 the NHL was the first professional sports league to use salary arbitration when the League and the players’ union included the process in its collective bargaining agreement for the 1970 season.170 NHL salary arbitration has been renewed with each new collective bargaining agreement, including the seventh and most recent CBA.171

Article 12 of the old NHL CBA governed hockey’s use of salary arbitration until the 2004–05 season.172 Only restricted free agents—i.e., players who still “belonged” to a particular team but who could not renegotiate their contracts with that team—qualified for salary arbitration.173 Although the arbitrators’ decisions were “final and binding on the parties,” owners retained limited “walk-away rights.”174 Since the hockey season typically begins mid-October of each year,175 all arbitration hearings occurred in the first two weeks of August and concluded before August 15.176

Under the last CBA, only the players were able to file for arbitration.177 The team ownership, on the other hand, decided “whether the arbitration award shall be for a one or two year contract.”178 The default term was one year if the club failed to delineate this detail.179 This provision favored the players because the ruling locked in the players for only one year rather than holding them to a two-year contract.180 After just one more year, the players could then renegotiate their contracts181 or enter into unrestricted free agency.182 On the other hand, a default term of two years favored club owners by limiting their players’ ability to match the yearly increase of salaries of other players from around the League.183

Table 9 Salary Arbitration Results and Data, MLB Arbitration (Year-by-Year)

| Year | Players | Owners |

2010 | 3 | 5 |

2009 | 2 | 1 |

2008 | 2 | 6 |

2007 | 3 | 4 |

2006 | 2 | 4 |

2005 | 1 | 2 |

2004 | 3 | 4 |

2003 | 2 | 5 |

2002 | 1 | 4 |

2001 | 6 | 8 |

2000 | 4 | 6 |

1999 | 2 | 9 |

1998 | 3 | 5 |

1997 | 1 | 4 |

1996 | 7 | 3 |

1995 | 2 | 6 |

1994 | 6 | 10 |

1993 | 6 | 12 |

1992 | 9 | 11 |

1991 | 6 | 11 |

1990 | 14 | 10 |

1989 | 7 | 5 |

1988 | 7 | 11 |

1987 | 10 | 16 |

1986 | 15 | 20 |

1985 | 6 | 7 |

1984 | 4 | 6 |

1983 | 13 | 7 |

1982 | 8 | 14 |

1981 | 11 | 10 |

1980 | 15 | 11 |

1979 | 8 | 5 |

1978 | 2 | 7 |

1977 | No arbitration | |

1976 | No arbitration | |

1975 | 6 | 10 |

1974 | 13 | 16 |

Total | 209 | 281 |

Source: The Associated Press; additional data on file from editors.

As with their baseball counterparts, NHL arbitrators were required to take into account various statistics and factors to guide them in making a final decision, including “the Compensation of any player(s) who is alleged to be comparable to the party Player.”184 The reliance on relative compensation created an undeniable upward spiral effect on players’ salaries throughout the NHL. Arbitrators had to have some figure regarding the market value of comparable players in order to determine the market value of the player who was party to the arbitration.185 Such a figure was necessary because NHL arbitrators were free to award any salary figure, unlike in Major League Baseball.186 Since NHL arbitrators had unlimited options, they relied more heavily on comparable players’ salaries to decide the arbitrations rather than on the players’ demands or the clubs’ offers.187

The result of this heavy reliance on comparable players’ salaries was an increase in salaries across the NHL. If one player had a successful year and he negotiated a new contract with a higher salary, comparable players demanded the same higher compensation. One player’s increased salary created a boon for comparable players.188 In NHL arbitration under the old CBA, the key for the player was to prove that he was comparable to another, more highly paid player.189 The pivotal role that comparable players’ salaries played in salary arbitration led to a relative increase in overall salaries.

NHL arbitrators had to decide their cases within forty-eight hours of the end of the arbitration hearings.190 Moreover, NHL arbitrations required only one arbitrator, while three person panels of arbitrators decide MLB hearings.191 In addition, NHL arbitrators’ decisions had to include both the “salary to be paid to the Player by the Club” and “a brief statement of the reasons for the decision, including identification of any comparable(s) relied on.”192 This differed from professional baseball’s arbitration rules, which do not provide for any explanation of the arbitrators’ decisions.193 In baseball, the final-offer element begs little need for such details since MLB arbitrators simply choose between two figures.

2. The Decisionmakers: How the NHL Chose Arbitrators Under the Old CBA

A potential distinction between the arbitration systems of hockey and baseball was the selection of arbitrators.194 Under the old NHL CBA, the League and the NHLPA jointly appointed eight arbitrators who were members of the National Academy of Arbitrators, and only one arbitrator decided each case.195 Likewise in the MLB, the owners and players’ association “annually select the arbitrators.”196 But MLB arbitrations are “assigned to three-arbitrator panels.”197

In a system of arbitration, a potential issue can be the procedure for selecting the arbitrators and the concern over the “repeat-player phenomenon.”198 For three reasons, the arbitrator-selection processes in both the MLB and the NHL (under the old CBA) avoided these potential problems. First, in both leagues, the opposing sides - the owners and the players - equally shared the ability to choose arbitrators.199 Second, the two sides in each league split the costs of the arbitrations, including paying the arbitrators.200 Finally, NHL and MLB arbitrations involved repeat-players on both sides of the hearing, so neither side had an advantage.201 Therefore, by the terms of their respective collective bargaining agreements, both the MLB and the NHL (under the old CBA) avoided potential problems in the selection of arbitrators.

3. The NHL’s Unique “Walk-Away” Provision

The last distinction of the NHL’s old salary arbitration system was that NHL arbitrations were not always final; the CBA provided owners limited “walk-away rights.”202 The walk-away right meant that arbitrations could have been appealed in certain circumstances,203 which differed from the absolute finality of the MLB’s salary arbitrations.204 The old CBA dealt with one and two-year arbitration decisions differently in regards to walk-away rights.205 If a team’s ownership chose to arbitrate a player’s salary on a one-year contract, the ownership had the option of walking away from the arbitration within seventy-two hours after the arbitrator announced his or her decision.206 Once the club did so, the player automatically became an unrestricted free agent, except in two circumstances.207 First, if the player accepted from another team an offer that was less than eighty percent of the award from the arbitration with the original club, the original club could elect to match the offer of the other team.208 Second, under certain circumstances and after the club had walked away from the arbitration, the player could have elected to accept the original club’s “qualifying offer” for one year and become a free agent at the end of that term.209

If a team’s ownership chose to arbitrate for a two-year contract, the ownership could again walk away from the arbitration decision within seventy-two hours of the announcement of the arbitration result.210 The difference, however, was the result of the team’s walking away. If a club walked away from a two-year arbitration decision, the player and the team had to enter into the one-year contract under the terms of the arbitration, and the player became an unrestricted free agent at the end of that one year.211

Thus, walking away from an arbitration decision on a two-year contract, as opposed to a one-year contract, created different results. Clubs could not fully walk away from arbitration on two-year contracts. They were stuck with the arbitration for a full year. This system yielded various incentives, including the incentive for a club unsure of losing the arbitration hearing to elect to arbitrate a one-year contract.212 In choosing to arbitrate a one-year deal, the club preserved full walk-away rights.

The final important aspect of the NHL’s walk-away right was the limit on the total number of times a club could exercise the right.213 Teams could walk away from arbitration decisions no more than three times in any two consecutive NHL years and no more than two times in a single arbitration season.214 The cap on walk-away rights encouraged teams to exercise the option sparingly. Since there was no limit to the number of restricted free agents on each team who could elect arbitration, the walk-away cap could have played a significant role in clubs’ arbitration strategy.215

4. The Latest Round of NHL Salary Arbitrations: Demonstrating How the Old CBA’s Arbitration System Malfunctioned

Although the 2004 NHL season did not commence as originally scheduled, off-season salary disputes during the summer of 2004 continued as usual.216 From August 1 to 15, 2004, arbitrators heard all of the League’s arbitration cases in Toronto.217 Arbitrators heard and decided nineteen disputes.218 Sixty-six players filed for arbitration, and the remaining forty-seven cases settled before going to arbitration.219

These numbers immediately reflect that, at least in theory, the NHL’s system operated as it should. The MLB’s “final-offer” system, by its very structure, encourages players and owners to settle before going to arbitration. Since the NHL did not use the final-offer system, players and owners should have resorted to arbitration more frequently than their baseball counterparts. Since 1990, 1469 baseball players have filed for arbitration, and only 182 went before arbitrators.220 Roughly ninety percent of the cases settled before arbitration.221 Of the 108 potential MLB arbitrations in 2004, only seven actually went to hearing.222 On the other hand, about twenty-eight percent of NHL cases typically end in arbitration.223

Baseball’s high settle rate was the subject of much interest on the part of the NHL owners during the 2004–05 lockout.224 Owners felt that players and agents held too much influence over the arbitration procedures of the old CBA225 and complained that the NHLPA won the majority of arbitration cases.226 As a result, NHL owners pushed for a final-offer system to replace the traditional arbitration procedures that the NHL used for decades.227 The results of the latest round of arbitrations undoubtedly encouraged owners to change the system. In 2004, the nineteen arbitrations yielded an average award of $3.12 million.228 Less than ten years ago the highest paid NHL player earned $5.5 million.229

While NHL owners at least recognized that there was something seriously wrong with the League’s salary arbitration system, baseball’s final-offer model would not slow the growth of the NHL players’ salaries. Although the NHL and MLB have used somewhat different arbitration systems over the years, the result has been the same in both leagues: skyrocketing salaries.230 The NHL need only look to the rising average and highest salaries in professional baseball to see that the MLB’s arbitration works no better than the NHL’s in keeping player salaries in check. Baseball players’ salaries have multiplied along with those in the NHL.231 The MLB system may encourage more settling and less arbitrating, but the product of the two leagues’ systems is the same. Moving to a final-offer system is a myopic suggestion that would fail to ameliorate the NHL’s systemic problem.

E. The National Hockey League’s Salary Arbitration System Under the New CBA (2005)232

1. The Mechanics of the NHL’s Salary Arbitration System Under the New CBA

Salary arbitration remains unchanged under the new CBA, except in two regards.233 First, players are eligible for salary arbitration after four years in the League instead of three.234 This provision favors the owners and signals their intent to decrease the prevalence of arbitration and its effects on players’ salaries.

The other change that the new CBA makes to arbitration relates to who can elect arbitration. For the first time in the history of NHL salary arbitration, teams also have the right to elect salary arbitration.235 For players who earn more than $1.5 million in their prior year, teams have the right to elect arbitration in lieu of making a “qualifying offer.”236 Teams also have the right to elect salary arbitration with respect to other certain restricted free agents who choose not to take the team to arbitration.237

The new CBA’s qualifying offer system should increase players’ salaries at a modest rate, while keeping players from resorting to arbitration. Players earning $660,000 or less are entitled to qualifying offers (“QOs”) at one-hundred and ten percent of their prior year’s salary.238 Players earning more than $660,000 and up to $1 million are entitled to QOs at 105 percent of their prior year’s salary.239 Finally, players earning more than $1 million are entitled to QOs at 100 percent of their prior year’s salary.240

These amendments to the old CBA’s salary arbitration system should help make the process more equal between owners and players. Since teams can elect arbitration in some circumstances, they will have the potential of lowering highly-paid players’ salaries when those players are not performing to their potential.241 Besides these minimal alterations, the new CBA leaves salary arbitration untouched.242 However, as the following analysis shows, other provisions of the new CBA render further changes to salary arbitration rules unnecessary.

2. Other Provisions of the New CBA and How They Relate to Salary Arbitration

As with the old CBA, the NHL’s new system of salary arbitration exists within the broader context of the entire collective bargaining agreement. The pertinent parts include: (1) players’ League revenue share, (2) team salary caps and floors, (3) maximum and minimum individual player salaries, (4) team revenue sharing, and (5) free agency.243

The first major step that the NHL took with the new CBA involves guaranteeing a player’s share of League revenues from each year.244 The player’s share will be fifty-four percent to the extent League revenues in any year are below $2.2 billion; fifty-five percent when League revenues are between $2.2 billion and $2.4 billion; fifty-six percent when League revenues are between $2.4 billion and $2.7 billion; and fifty-seven percent when League revenues in any year exceed $2.7 billion.245

These guarantees seem to favor the players at first glance. However, during the 2002–03 season, the NHL spent seventy-five percent of League revenues on players’ salaries.246 The NHL has not spent fifty-seven percent of its revenues on player costs since 1994.247 The players’ share appears to represent a significant step backwards. The NHL is attempting to use this provision to curb player costs that spiraled out of control during the life of the last CBA.

….

The CBA’s limitation of the players’ share of League revenues relates to salary arbitration because salary arbitration has played a pivotal role in pushing players’ salaries up.250 Arbitration under the old CBA inflated players’ salaries without a real limit.251 However, under the new CBA, the limitation on the players’ share of League revenues creates somewhat of a cap on the augmenting effect that arbitration can have on players’ salaries.252

This limitation on salary growth is displayed no more prominently than in the new CBA’s imposition of a team salary floor and cap.253 Under the new CBA, the payroll range for each franchise in season one (2005–06) is $21.5 million to $39 million.254 [Ed. Note: The payroll range in 2010–11 was $43.4 million to $59.4 million.] The salary range should help create more parity among the League’s teams, but more importantly, the hard salary cap will effectively restrain players’ salaries.255 The pitfall of the NHL’s salary arbitration scheme under the old CBA was that player-friendly arbitration artificially inflated salaries across the League without any real restraint.256 The new CBA’s hard salary cap will effectively eliminate this problem.

Similarly, the new CBA’s cap on individual player salaries will curtail the inflationary effects of salary arbitration.257 Under the old CBA, one aspect of salary arbitration that tended to increase players’ salaries League-wide was the relative nature of arbitrators’ decisions combined with the lack of a cap on individual salary awards.258 The new CBA ameliorates this problem by regulating the maximum amount that any one player may make on each team.259

….

Notes

….

3. Bob Foltman, Hockey May Rise from Grave, CHI. TRIB., Feb. 19, 2005, § 3, at 1.

4. Rev Up the Zamboni, TORONTO STAR, July 14, 2005, at A20. The end of the lockout was a long-time coming, as players and owners expressed their desire to simply get the game back on the ice. Id. “To be totally honest, I really don’t care what the deal is anymore,” Philadelphia Flyers player Jeremy Roenick said. “All I care about is getting the game back on the ice.” Id.

5. Helene Elliott, New Game for the NHL, L.A. TIMES, July 23, 2005, at D1. Some highlights of the new rules include: no more ties (shootouts will be played until there is a winner), a larger offensive zone (goals will be closer to the boards and the neutral zone will be reduced), a bigger shooting area in the goal (goaltenders’ pads, gloves, and other equipment will be reduced in size), and fewer slowdowns (officials will show “zero tolerance” to interference, hooking, and holding obstruction by defenders). Id. at D9.

6. Id. The new logo has the same shield used in the previous NHL logo, but it is now silver and white. Id.

7. It is difficult to distinguish between the League’s desire to update the game’s rules and its fervent pleading with fans to return. See Tim Tucker, Image, Scoring Require a Boost: The New NHL; League Outlines Plans to Increase Offense and Accessibility in Hopes of Coaxing Fans to Return after Costly, Unprecedented Lockout, ATLANTA J.-CONST., July 24, 2005, at 1E. Fans’ support of the NHL no doubt supplies cash to the League for it to operate and pay its players. However, disagreement over how the League divides that money between its owners and players caused the 2004–05 labor dispute.

8. Of all of the professional sports leagues in North America, the National Football League (NFL), the Major League Baseball (MLB), the National Basketball Association (NBA), and the NHL gross the highest revenue. See Ted Kulfan, Comparing the Leagues’ Financial Arrangements, DETROIT NEWS, Oct. 13, 2004, at 6G. The above list is in order of estimated annual revenue, with the NFL grossing the greatest amount and the NHL hanging on at the bottom of the list. Although the NBA and the NHL include “national” in their proper names, these two leagues have franchises in both the United States and Canada. NBA.com, Teams, http://www.nba.com (place cursor on the “Teams” hyperlink at the top of the page for a drop-down menu) (last visited Dec. 17, 2005); NHL.com, Teams, http://www.nhl.com/teams/index.html (last visited Dec. 17, 2005). Although presently both leagues consist of fewer Canadian Franchises than previously, the NBA still includes the Toronto Raptors, and the NHL has six Canadian teams. Migration of Franchises: Teams on the Move, SPORTS ILLUSTRATED, Dec. 27, 2004, at 110, 110-12. The NBA’s only other Canadian team, the Vancouver Grizzlies, moved to Memphis, Tennessee in 2001, after existing just six years in British Columbia. Id. at 112. The NHL started with two of its “original six” teams playing home games on Canadian ice (Montreal and Toronto). Id. There have been as many as eight Canadian hockey franchises in the NHL at one point, but as of 2005 there were only six (Montreal, Toronto, Ottawa, Edmonton, Calgary, and Vancouver). Id. The NFL has never had a Canadian franchise, due partly to the presence of the Canadian Football League. See generally The Official Site of the Canadian Football League, http://www.cfl.ca (last visited Dec. 17, 2005). Major League Baseball had two Canadian teams (Montreal and Toronto) from 1977 to 2004, but the Montreal Expos moved to America’s capital and became the Washington Nationals in 2005. Migration of Franchises: Teams on the Move, supra, at 111. Before relocating the Expos to Washington, D.C., the MLB considered several other more southerly locations, including Monterrey, Mexico. Ed Waldman, Also-ran Cities Set to Pinch Hit if D.C. Drops Out of Race, BALT. SUN, Dec. 16, 2004, at 5C. The four major leagues have never actually had a franchise in Mexico. Id. For a comprehensive look at the past and future of professional sports franchises in Canada see Heather Manweiller & Bryan Schwartz, Time Out: Canadian Professional Sports Team Franchise-Is the Game Really Over?, 1 ASPER REV. INT’L BUS. & TRADE L. 199, 199-210 (2001).

9. Americans follow other sports much more intensely than hockey, as shown by the revenue differences in the four largest leagues. Kulfan, supra note 8, at 6G. The NHL, for instance, generates gross revenues that are less than half of what the NFL makes. Id. According to a December 2004 Gallup poll, over three-fourths of the people surveyed did not consider themselves fans of hockey. Gallup Poll Social Series: Lifestyles (Dec. 5, 2004—Dec. 8, 2004), http://institution.gallup.com/documents/question.aspx?question=151494&Advanced=0&SearchConType=1&SearchTypeAll=hockey (last visited Dec. 17, 2005). Less than twenty percent of responders considered themselves fans of hockey. Id. Another Gallup poll found that only twenty-three percent of Americans described themselves as hockey fans. Go Figure, SPORTS ILLUSTRATED, Dec. 27, 2004, at 36. In that same poll, respondents ranked hockey tenth among the eleven sports listed in the survey, with hockey coming in behind figure skating. Id. These numbers demonstrate that a further decline in hockey’s popularity among Americans would be no shock; however, hockey is a part of the history and national pride of Canada. Soriano, Rangers Avoid Arbitration, ORLANDO SENTINEL (FLA.), Jan. 18, 2005, at C3. Historians believe that the first modern hockey league started in Kingston, Ontario in 1885. NHL.com Hockey History, http://nhl.com/hockeyu/history/evolution.html (last visited Dec. 17, 2005). The champion of professional hockey has won the Stanley Cup—one of the most recognizable trophies in the world—since 1893. NHL.com Stanley Cup History, http://nhl.com/hockeyu/history/cup/cup.html (last visited Dec. 17, 2005). Over a century ago, Lord Stanley, the late Earl of Preston and Governor General of Canada, purchased the first Cup for the “champion hockey team in the Dominion (of Canada).” Id. Canada continues to support a strong Olympic hockey program, with the Canadian team winning the 2002 Olympic Gold Medal. Stand on Guard for Thee: Canada Captures First Hockey Gold Medal in 50 Years, CNNSI.com, Feb. 24, 2002, http://sportsillustrated.cnn.com/olympics/2002/icehockey/news/2002/02/24/usacanadaap/ (calling hockey Canada’s “national sport”). The NHL is to Canada what the NFL is to the United States. Soriano, Rangers Avoid Arbitration, supra, at C3. During the cancelled season of 2004–05, a bored and disappointed NHL fan from Winnipeg, Manitoba wrote to the Kansas City Star: “Now we just sit around in our basements and drink antifreeze.” Id.

10. Pierre Lebrun, Blame it On ‘97–’98, EDMONTON SUN (ALTA., CAN.), Sept. 21, 2004, at SP2.

….

12. Michael Rosenberg, Bettman Created this Mess, THE RECORD (Bergen County, N.J.), Oct. 24, 2004, at S6. As with any spectator sport, the NHL’s fan base is integral to its success as a financially viable and socially important entity. NHL CBA, CBA FAQ: NHL Announces Cancellation of 2004–05 Season, http://www.nhl.com/nhlhq/cba/index.html (last visited Dec. 17, 2005). When NHL Commissioner Gary Bettman officially cancelled the 2004–05 season, he apologized to the fans, saying he “[was] truly sorry.” Id. “Every professional sports league owes its very existence to its fans,” he added. Id.

13. See Michael Steinberger, Cap Row May Stop the Puck Here, FIN. TIMES (LONDON), Sept. 14, 2004, at 18.

14. Kulfan, supra note 8, at 6G; Larry Brooks, Paying for Lockout Tix off Fans, N.Y. POST, Oct. 3, 2004, at 60; Doug Robinson, NHL’s on Strike and Nobody Even Noticed, DESERET MORNING NEWS (SALT LAKE CITY), Nov. 1, 2004.

15. Helene Elliott, The NHL Lockout: A “Bleak Day,” L.A. TIMES, Sept. 16, 2004, at D1.

16. Elliott, supra note 5, at D1. The new CBA imposes a salary cap and floor ($39 million and $21.5 million, respectively for the 2005–06 season) on each team. Id. Additionally, the new CBA guarantees players will receive between 54% and 57% of League revenues each year, depending on the level of League revenues for those years. Id. The new CBA also imposes restrictions on individual salaries. Id.

….

27. NHL.com, 2002–03 League-Wide URO Results, http://www.nhl.com/nhlhq/cba/archive/bythenumbers/uroresults.htm l (last visited Dec. 17, 2005) [hereinafter 2002-03 URO]. These numbers indicate that the NHL operated at a $273 million deficit for the 2002–03 season alone. Id.

….

30. See Tucker, supra note 7, at 1E. In 2004, the Former Chairman of the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), Arthur Levitt, called professional hockey a “dumb investment” after heading a year-long assessment of the NHL’s financial situation. Scott Van Voorhis, On Thin Ice: Report: Most NHL Teams Lose Millions, BOSTON HERALD, Feb. 13, 2004, at 39. Levitt’s study produced the Unified Report of Operations (URO), which revealed that the NHL lost about $300 million during the 2002–03 season. Id. The study, however, has been a source of continued controversy, as the NHLPA and the NHL quarrel over just how bad is the NHL financial situation. Id. (quoting the NHLPA referring to Levitt and his associates as a “team of hired gun accountants,” who the NHL paid “in the $500,000 range” to produce a “sobering” survey to convince the NHLPA and fans that drastic changes to the League’s salary system must follow). The Levitt Report revealed, not surprisingly, that the greatest source of income for the NHL is the money fans pay to see games. Id. Gate receipts totaled $997 million of the League’s combined $1.494 billion revenue in 2002–03. Id. Broadcasting-media brought in less than half of the total from gate receipts, or $449 million. Id. The NHLPA continued to challenge the accuracy of these numbers as the labor lockout of 2004–05 continued. Dave Hannigan, Ice Hockey: Impasse in Labour Dispute Means Big Freeze for Whole NHL Season: Greed Blamed for Shut-down, THE GUARDIAN (LONDON), Feb. 17, 2005, at 29 (noting that “[a]fter 38 meetings over two years, their [owners’ and players’] evaluations of the sport’s [NHL’s] financial condition still differed too greatly [to reach a labor agreement]”).

31. 2002–03 URO, supra note 27; see also http://www.nhl.com/nhlhq/cba/archive/bythenumbers/historicalresults.html (last visited Dec. 17, 2005).

….

33. Id.

34. Id.

35. Chris Snow, You Say Tomato, I say …; Here are the Key Issues the League and the National Hockey League Players’ Association Dispute, STAR TRIB. (MINNEAPOLIS), Sept. 15, 2004, at 3C. The Pittsburgh Penguins filed for bankruptcy in 1974 and 1998, while the Los Angeles Kings went bankrupt in 1995. Kevin Allen, Senators File for Bankruptcy, but Will Keep Skating, USA TODAY, Jan. 9, 2003, available at http://www.usatoday.com/sports/hockey/nhl/senators/2003-01-09-bankruptcyx.htm. The Ottawa Senators filed for bankruptcy in January 2003. Id. A week later, the Buffalo Sabres followed suit. Sports FYI: Solich Names Assistants, TULSA WORLD (OKLA.), Jan. 14, 2003, at B2. These are the only four existing major professional sports franchises to go bankrupt. Id.

36. 2002–03 URO, supra note 27.

37. Id.

38. Id.

39. Elliott, supra note 15, at D9; Commish Claims Locked-out Union in Denial, ESPN.com, Nov. 2, 2004, http://sports.espn.go.com/espn/print?id=1914328&type=story.

40. A January 2005 USA Today/Gallup Poll discovered that fifty percent of sports fans would “not be disappointed at all” if the NHL/NHLPA labor disputes cancelled the 2004–05 NHL season. Mike Brehm, Poll: No NHL Would be No Biggie for Sports Fans, USA TODAY, Jan. 11, 2005, at 3C. ESPN Analyst and Former NHL Goaltender Darren Pang believed that “even the casual sports fans last year, going into Game 7 of [the] Tampa Bay-Calgary (Stanley Cup Finals), were somewhat excited about our sport.” Id. However, fan interest has considerably declined, as another recent Gallup Poll conducted in December 2004 found that only 23 percent of Americans considered themselves hockey fans. Go Figure, supra note 9, at 36.

41. Rosenberg, supra note 12, at S6.

42. The Stanley Cup Finals are the championships of the NHL. See NHL.com, Stanley Cup, http://nhl.com/hockeyu/history/cup/index.html (last visited Dec. 17, 2005). The Stanley Cup finals are a best-of-seven format, which means that the first team to win four games wins the NHL championship. Id. The seventh game of the series, then, is the “decisive” game, since the winner of Game Seven also wins the championship. Therefore, given the relative importance and decisiveness of the final game in the series, Game Seven of the 2004 Stanley Cup Finals should have attracted a large audience.

43. Vlessing, supra note 11, at Up Front. A TV rating is “the estimate of the size of a television audience relative to the total universe, expressed as a percentage.” Top Ten Primetime Broadcast TV Programs for Week of 2/07/05–2/13/05, Nielsen Media, http://www.nielsenmedia.com/index.html (last visited Sept. 19, 2005). “As of September 20, 2004, there [were] an estimated 109.6 million television households in the U.S. A single national household ratings point represents 1%, or 1,096,000 households.” Id. Therefore, the 5.4 rating from the final game of the 2004 Stanley Cup Playoffs translated to about 5,918,400 viewers. Comparatively, on February 6, 2005, Super Bowl XXXIX—the NFL’s championship equivalent of Game Seven of the Stanley Cup Playoffs—attracted a 41.1 rating, or about 45,045,600 viewers. David Barron, Hamilton Eagerly Eyes His Milestone Season, HOUSTON CHRON., Feb. 11, 2005, Sports, at 2.

44. Vlessing, supra note 11, at Up Front.

45. Rick Reilly, TV Poker’s a Joker, SPORTS ILLUSTRATED, Oct. 25, 2004, at 156; see generally Larry Brooks, Eve of Destruction; Owners Are Out to Ruin NHL, N.Y. POST, Sept. 12, 2004, at 62. ABC is a basic channel that has a potential of reaching 109.6 million television households in the United States alone. Top Ten Primetime Broadcast TV Programs for Week of 2/21/05-2/27/05, Nielsen Media Research, available at http://www.nielsenmedia.com/index.html (last visited Sept. 20, 2005). Fewer television households subscribe to a cable service, so cable networks, like ESPN, have fewer potential viewers. Id.

46. Vlessing, supra note 11, at Up Front. Before 2005, the NHL had a five year, $600 million contract with ABC and ESPN. Joe LaPointe, ABC and ESPN Script Grabs More Eyeballs, N.Y. TIMES, June 6, 2003, at D5. The NHL has traditionally had smaller television contracts than the NBA, NFL, and MLB. Id. Other professional sports leagues consistently sign television contracts that dwarf the NHL’s largest TV deal ever: five-years, $600 million (from 1999–2004). Todd Jones, NHL Reached for the Sky, But It Really Needed Firm Foundation, COLUMBUS DISPATCH, Feb. 18, 2005, at B3. The 2005 network television deals of other pro sports leagues included $17.6 billion for the NFL, $4.7 billion for the NBA, and $3.35 billion for the MLB. Id. Even professional racecar driving demanded a larger TV deal than professional hockey, with NASCAR holding on to a $2.8 billion deal from network TV during 2005. Id.

47. Elliott, supra note 5, at D1. Speaking on the need for these rule changes, Commissioner Gary Bettman emphasized the need to “drop the puck on a fresh start for the NHL.” Id. The NHL unveiled its new rules in an effort to divorce fans’ feelings about “the long, dark days of the lockout” and cancelled season of 2004–05 with the NHL and professional hockey in general. Id.

48. Migration of Franchises, supra note 8, at 112. Those nine expansion teams and the years the NHL introduced them are: San Jose Sharks (1991), Ottawa Senators (1992), Tampa Bay Lightning (1992), Florida Panthers (1993), Anaheim Mighty Ducks (1993), Nashville Predators (1998), Atlanta Thrashers (1999), Columbus Blue Jackets (2000), and Minnesota Wild (2000). Id.

49. Elliott, supra note 15, at D1. Examples of recently created or relocated southerly NHL franchises include the Phoenix Coyotes (formerly the Winnipeg Jets until 1996), Nashville Predators (expansion team of 1998), and Carolina Hurricanes (formerly the Hartford Whalers until 1997, when they relocated to Raleigh, North Carolina). Migration of Franchises, supra note 8, at 112.

50. See Chris Snow, The Lost Season?: Lockout Begins Tonight; The Puck Stops Here; NHL, Players Remain Miles Apart as Lockout Appears Certain, STAR TRIB. (MINNEAPOLIS), Sept. 15, 2004, at 1C.

51. In 2004, players’ salaries ate up seventy-five percent of the NHL’s revenues. Dave Joseph, NHL Season Put on Ice: Life Goes On, SUN-SENTINEL (FT. LAUDERDALE, FLA.), Feb. 17, 2005, at 1A.

52. 2002–03 URO, supra note 27.

53. Id.

54. Mike Loftus, NHL Update; Little Movement in Negotiations; Owners, Players Still Heading Toward Lockout, THE PATRIOT LEDGER (QUINCY, MASS.), Sept. 4, 2004, at 47. The NHL’s losses continued to mount, as the 2004–05 non-season prevented even the possibility that the NHL could generate a profit. J.P. Giglio, RBC, Canes Made Provisions, THE NEWS & OBSERVER (RALEIGH, N.C.), Feb. 19, 2005, at C3. While the owners amassed a $300 million reserve fund to survive the cancelled season, the teams cannot produce revenues without conducting any games. Id.

55. Kulfan, supra note 8, at 6G. Major League Baseball (MLB) dedicates 63% of its revenue to players’ salaries, while the NBA and the NFL spend 58% and 64%, respectively, of their revenues on their players. Id.

56. Id. The MLB earns about $4.1 billion per year, while the most successful league, the NFL, grosses about $5 billion. Id.

57. The first franchise to file for bankruptcy was the Pittsburgh Penguins. Jenny Wiggins, US Sports Tackle TV Cash Issue: Credit Analysts are Watching for Moves off the Screen, FINANCIAL TIMES (LONDON), Nov. 14, 2003, at 45. Three other teams—Los Angeles, Ottawa, and Buffalo—have since done the same. See Allen, supra note 35; Sports FYI: Solich Names Assistants, supra note 35, at B2.

58. Loftus, supra note 54, at 47.

59. Id.

60. Kulfan, supra note 8, at 6G.

61. See Tim Sassone, Looks Like a Lockout as Deadline Looms: All Signs Pointing to Long Labor Dispute for NHL, CHI. DAILY HERALD, Sept. 14, 2004, at Sports 1.

62. This subsection gives the reader a basic understanding of the general business structure of the NHL and of the traditional procedural elements of arbitration as one of the basic forms of alternative dispute resolution. For a more detailed look at the franchise system of professional sports see Kenneth L. Shropshire, THE SPORTS FRANCHISE GAME (1995).

63. The American Arbitration Association (AAA), the largest alternative dispute resolution institution in the world, has handled over two million cases, with many in the field of labor. See American Arbitration Association Dispute Resolution Services Worldwide, Fast Facts, http://www.adr.org/FastFacts (last visited Dec. 17, 2005). In 2002 when commercial disputes declined, the AAA handled an increased number of labor cases. American Arbitration Association Dispute Resolution Services Worldwide, 2003 President’s Letter and Financial Statements 4, available at http://www.adr.org/si.asp?id=1543, at 4 (last visited Dec. 17, 2005).

64. See Michael Arace, NHL’s Lost Season: Nuclear Winter, COLUMBUS DISPATCH, Feb. 17, 2005, at E1. “The reason” for the 2004–05 NHL lockout and eventual season cancellation was that “the NHL and its players’ association couldn’t resolve how to split revenues from the $2.1 billion industry.” Id.