CHAPTER TEN

Labor Matters: Athlete Compensation

INTRODUCTION

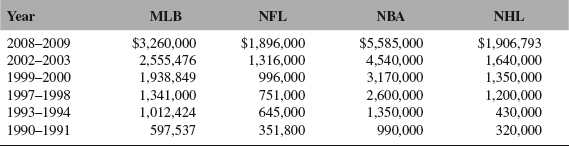

It is well known that professional athletes competing in each of the four major North American sports leagues receive lucrative compensation. In 2008 and 2009, average salaries across these leagues were $5.585 million in the NBA, $3.26 million in MLB, $1.9 million in the NHL, and $1.9 million in the NFL. What is not well known is how these salaries are determined. Professional athletes are often perceived as being overpaid instead of merely well paid. This reflects a misunderstanding of the relevant marketplace for athlete compensation. A comparison of athlete salaries to those of the average person is misleading. Instead, athletes should be regarded as entertainers when it comes to compensation. When considered in this manner, athlete compensation is quite reasonable. Much like entertainers, there is a limited supply of highly skilled athletes who the average person desires to watch either live or on television. This is a signifi-cant reason why athletes (and entertainers) are able to earn such high salaries. (See Table 1 for a list of the average salary growth in each league.)

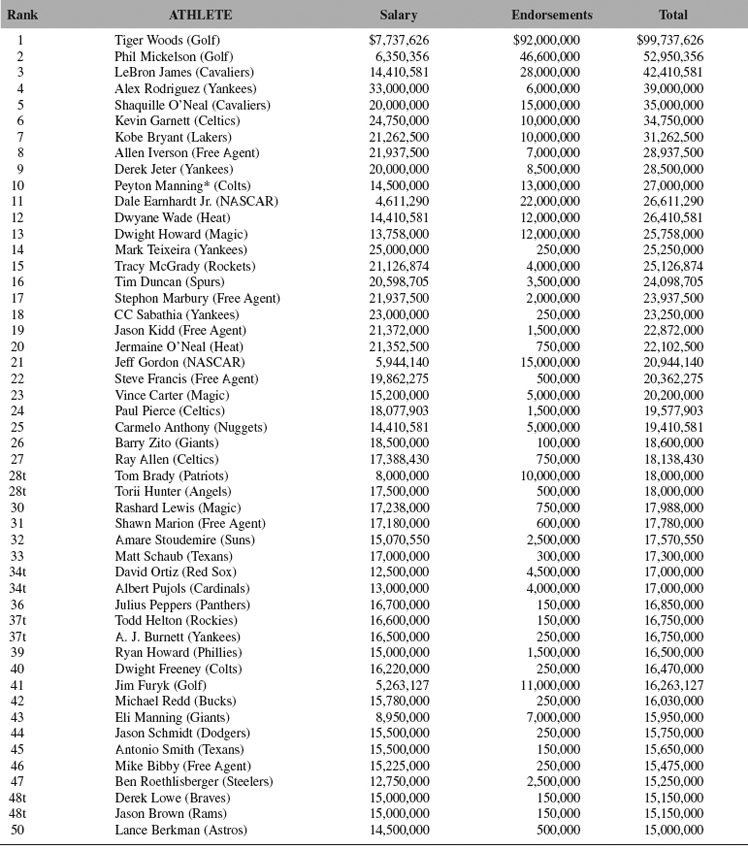

There is, however, an area in which it is fair to compare an athlete’s salary to the average worker’s—the economic justification for how much one is paid. Individuals who are employed in a free and open marketplace are compensated based on their marginal revenue product (MRP); that is, how much the individual employee contributes to the employer’s revenues. Conversely, individuals who are employed in a restricted, uncompetitive marketplace are not compensated based on their MRP. Instead, the employer retains most of the MRP, and the individual is compensated (and some would say exploited) at a more conservative rate. See Table 2 for the top American earners in U.S. sports.

The MRP concept explains why the salaries of professional athletes typically increase with the athletes’ years of experience. A truncated version of the reserve system that set athlete salaries in each league at artificially low rates until the mid-1970s in MLB (and later in other leagues) still exists. Similar to the reserve system that perpetually bound a player to a team at the team’s discretion, each league limits player access to a competitive marketplace for a period of years at the beginning of a player’s career. Not surprisingly, most studies indicate that athletes tend to earn close to the minimum salary established in the league’s collective bargaining agreement during this monopsonistic period. The team captures most of the athlete’s MRP at this stage of his career. After this initial period, the player in each league gains increased but still restricted access to the marketplace (and the full value of the MRP) for a period of years as a result of restricted free agency, salary arbitration, or both. Upon completing this stage, the athlete gains access to the open marketplace via unrestricted free agency. This allows the player to realize close to the full value of his MRP.

In professional sports leagues, the salary of an individual athlete is determined pursuant to the athlete compensation framework established by collective bargaining between the union and management. This determination is typically accomplished through a negotiation between a team and the athlete’s representative. Although the collective bargaining agreement establishes the parameters for this negotiation, the salary for any particular athlete depends on a number of factors both internal and external to that athlete. First, of course, are the factors internal to the athlete, which exist outside of the context of the collective bargaining agreement. The athlete’s skill level, position, experience, injury history, drawing power, and league all impact the compensation earned. A highly skilled, experienced, and seldom-injured athlete playing a “glamour” position in a thriving league will be better compensated than one lacking any of these qualities. In addition, several external factors that are products of the collective bargaining agreement can either increase or decrease athlete salaries. Free agency and salary arbitration increase athlete salaries, whereas a salary cap, luxury tax, and the presence of a reserve system can all decrease athlete salaries. Outside of the collective bargaining agreement, the presence of a competitor league typically leads to dramatic salary increases. These external factors require further elaboration.

Sources: National Football League Players Association, National Basketball Players Association, National Hockey League Players Association, and Associated Press.

As previously mentioned, free agency grants athletes access to a more open marketplace for their services. There are two basic types of free agency: restricted and unrestricted. An athlete is granted restricted free agency after completion of the initial reservation period at the beginning of his career. Restricted free agency provides the athlete whose contract has expired the ability to receive employment offers from other teams in the same league. The athlete’s movement to other teams is restricted, however, because the current employer typically has a right to match the outside offer and maintain the athlete’s services under those exact terms. Alternatively, the team can choose to allow the player to defect and may receive compensation from the new team in exchange for this player. Thus, restricted free agency allows the athlete to obtain a salary increase through the introduction of a quasi-open marketplace. The salary effect is lower if a compensation mechanism is in place, because this places a cost on outside teams that solicit new players. Conversely, the less restrictive the compensation mechanism, the greater the effect of restricted free agency on player salaries.

Unrestricted free agency provides more experienced athletes whose contracts have expired with the opportunity to receive offers from all league teams in an open marketplace. This allows players to receive fair market value for their services. Athlete compensation increases significantly with the arrival of free agent eligibility. It should not be surprising, then, that owners are generally opposed to free agency because of the effects that it has on player salaries. Though now accepted as an essential characteristic of the athlete compensation framework, owners still attempt to impose as limited a system of free agency as possible. However, free agency itself is not necessarily bad for owners. Rather, it is the intersection of free agency with the laws of supply and demand that negatively impacts owners. Unrestricted free agency is not available to every athlete every year. Instead, only those athletes with a particular level of experience whose playing contracts have expired are eligible for free agency. By limiting the number of athletes who are eligible for free agency each year, the supply of players entering the free agent marketplace is artificially lowered. This allows free agents to receive higher salaries than they would in a truly open marketplace where every player is a free agent every year. Doing so would flood the marketplace and depress salaries. So athletes actually have an interest in limiting their access to free agency in order to reap its maximum benefits.

Salary arbitration provides owners and athletes with a method of resolving disputes over the athlete’s salary for the upcoming season while ensuring that the athlete will continue his employment with the team uninterrupted by a holdout over salary. Salary arbitration allows athletes who have completed the initial phase of their careers to compare themselves to other similarly situated athletes in the marketplace in order to obtain salary increases. Athletes have been quite successful in doing so, especially because of the intersection that has occurred between free agency and salary arbitration. The free market effects of free agency have trickled down to the salary arbitration process.

The presence of a competitor league provides athletes with an attractive employment alternative. A new league needs players, the most talented and well known of whom are employed in the established league. These leagues do not abide by their rivals’ collective bargaining agreements. Thus, unencumbered by the established league’s reserve system, all athletes whose contracts have expired are able to gain access to an open marketplace regardless of experience. Historically, the introduction of another bidder for their services has led to a dramatic increase in players’ salaries. Similar to other industries, competition among employers in the labor marketplace benefits the employees—in this case, the athletes.

Over the years, owners have devised various tactics that attempt to depress athlete compensation below competitive levels. The reserve system accomplished this very effectively by perpetually binding a player to a team, thereby preventing him from obtaining a market-level salary. Since the evisceration of the reserve system nearly a generation ago, the collective bargaining process has yielded the development of salary caps and luxury taxes.

Source: Reprinted courtesy of SPORTS ILLUSTRATED: “The Fortunate 50” by Jonah Freedman, August 2, 2010. Copyright © 2010. Time Inc. All rights reserved. With data from “Tiger Tops SI’s List of Top Earners for Sixth Consecutive Year,” SportsBusiness Daily, July 2, 2009.

Notes: *Manning in 2009 has distributed $500,000 in grants through his PayBack Foundation to charities in Indianapolis, near the University of Tennessee (his alma mater), and in his hometown of New Orleans.

Candidates for the U.S. 50 had to be American citizens. SI consulted players associations, tour records, agents, and news reports to compile the list. Endorsement estimates came from Burns Entertainment & Sports Marketing, other sports-marketing execs and analysts, and agents. [Ed. Note: Covers the period from July 1, 2008–June 30, 2009.]

The presence of a salary cap provides a team with a degree of cost certainty in addressing their single highest expenditure—athlete salaries. A salary cap is actually a revenue sharing device for owners and athletes, with the owners guaranteeing the players a significant percentage of certain revenue streams. A hard cap places an absolute limit on this percentage and allows for few exceptions to this limit. A soft cap sets a limit but allows for a number of exceptions.

Another type of cost-containment mechanism is a luxury tax. Rather than limit the amount that each team can pay its players, a luxury tax gives a team a disincentive to exceed paying its players beyond certain salary levels by penalizing them for their excessive spending. This penalty is set at a percentage of the dollar amount of the excess. The higher the percentage and the lower the tax threshold, the greater the disincentive on the team.

The excerpts chosen for this chapter describe all of the aforementioned issues and ideas in great detail. In the first article, Quirk and Fort establish the broad framework for the discussion of athlete compensation. In the next selection, Kahn explains the impact of reserve systems, rival leagues, free agency, and incentives on the labor market for professional athletes. Berri, Brook, and Schmidt analyze the statistical determinants of salary for NBA players in the next selection. Michael Lewis’ bestseller Moneyball brought significant attention to the use of statistical information by teams attempting to gain a competitive advantage, a tactic that has since proliferated not only in baseball but in other sports as well. The reading from Hakes and Sauer examines the economics of this phenomenon in MLB, whereas Bill Gerrard’s excerpt does so in the context of more complex sports that rely on a greater degree of interdependence of players, specifically looking at English professional soccer. The next three readings review provisions of the collective bargaining agreements in North American professional sports leagues that inflate and deflate player salaries. Andrew Healy reviews teams’ inefficient use of the free agency system in MLB, whereas Stephen Yoost examines salary arbitration in the National Hockey League. Richard Kaplan then reviews the deflationary luxury tax system utilized in the NBA since the late 1990’s. In the final article, Duffy reviews the Bosman decision that led to the demise of the reserve system in European soccer and introduction of unfettered free agency, analyzing its impact on the sport throughout the continent.

FRAMEWORK

PAY DIRT: THE BUSINESS OF PROFESSIONAL TEAM SPORTS

James Quirk and Rodney D. Fort

PRO ATHLETES AS ENTERTAINERS

… Unlike unions in most industries, players’ unions do not negotiate “standard wage” policies binding on most or all members. Instead, individual player salaries are determined by direct negotiation between the player and the team owner. Unions do bargain for league-wide minimum salaries, so the changes over time in minimum salaries reflect in part changes in the bargaining power of unions….

While average salary levels are much lower for football and hockey, football (and, to a lesser extent, hockey) also showed marked increases in real salary levels in the 1980s, despite the restrictions on player mobility (free agency) for NFL football relative to baseball and basketball. Thus, in rounding up the usual suspects to explain the real growth in player compensation in all sports, free agency is not the only candidate. Other factors must be at work as well, including the impressive increase in demand for pro team sports tickets, and the striking increase in value of pro sports television rights for all pro team sports…

But the common perception of fans is that pro athletes are wildly overpaid, and that free agency is the culprit. Every red-blooded American boy wants to grow up to be a major leaguer in some sport, and most red-blooded American adult males would toss their careers in a minute if they thought they had a chance to make it in the pros. One example of this sports idolatry can be found in the vastly overinflated assessments that high school athletes make about their chances of turning pro, and, in turn, the similar mistaken perceptions that possess college athletes. Given that many fans would pay for the privilege of playing in the majors (and some actually do pay for the major league experience at adult major league baseball fantasy camps), fans find it a little difficult to accept the fact that pro athletes demand and get salaries in the six- or seven-figure range.

One way to add some perspective to the rise in real salaries for pro athletes is to look at the compensation paid to other entertainers. Perhaps Norby Walters put it best during his 1988 trial for signing college athletes to pro contracts prior to expiration of their college eligibility: “No difference. A sports star is a rock star. They’re all the same.”1 Walters’ insight is right on the mark—star pro athletes are entertainment stars every bit as much as movie and rock stars. The same factors are at work determining the sizes of the big incomes in sports as in other areas of entertainment. These factors are demand by the public for tickets to see stars, the rarity of skilled and/or charismatic individuals with star qualities (in the economist’s jargon, an inelastic supply of talent), and the bargaining power of stars relative to that of the promoters who hire them (team owners in the case of pro sports). In explaining the rise in salaries for sports stars, both increases in the demand for their output and changes in their bargaining power (for example, free agency’s replacing a reserve system) are relevant.

….

In an interesting analogy to the elimination of the reserve clause in baseball, movie entertainers’ earnings skyrocketed with the breakdown of the “contract player” mode of operation in place in the motion picture industry until the 1950s. Studio owners of that era, much as sports team owners today, argued vigorously that the runaway growth in star salaries spelled disaster for their industry. True to predictions, the earnings of movie stars did go up dramatically, but the U.S. motion picture industry remains quite healthy even up to the present time, and is one of the few American industries that has retained its competitive edge in an international setting.

It is interesting that the public perception of the importance of rising salaries for entertainers is so different between movie stars and pro athletes. That star salaries in pop music or the movies cause little public concern is borne out by where news on salaries can be found…. If the level of discussion about salaries in movies and in popular music is a murmur, then it is a high-pitched scream in pro sports….

To fans, the answer to why pro sports are different from other entertainment endeavors is obvious. Other mass entertainment media do not bring philosophers to their defense, lead presidents of the United States to throw out first pitches, or give poets pause to reflect. Whatever the reason, pro team sports are viewed differently from the other mass entertainment industries by almost everyone—fans, sportswriters, players, and owners. But there are some fundamental economic facts of life that apply across the board to all labor markets, including the market for rock stars and pro sports players.

THE WORKINGS OF THE PLAYER MARKET

The market for any labor service, such as the market for the services of pro athletes, follows the good old law of supply and demand and operates on the basis of bids and offers by teams and players. Looking at things from the point of view of any team, we can calculate the most that a profit-oriented team would offer a player; it is the amount that the player would add to the team’s revenue if he were signed. In the jargon of economists, as noted earlier, this is the player’s marginal revenue product, which we will refer to as his MRP. The player’s MRP is the most a team would pay a player because paying a player more than this would decrease team profits; on the other hand, signing a player for anything less than his MRP means that adding the player increases profits for the team.

… George Steinbrenner … was asked once how he decided how much to pay a player. He said, “It depends on how many fannies he puts in the seats.” That was George’s way of saying it depends on the player’s MRP….

From the player’s point of view, the least he would be willing to accept as a salary offer to sign with a team is what he could earn in his next-best employment opportunity (taking into account locational and other nonmonetary considerations). We hesitate to push our luck, but economists refer to this next-highest employment value as the player’s reservation wage. If a team offers a player less than his reservation wage, the player would simply reject the offer and remain employed in his next-best opportunity.

The player’s MRP and reservation wage give the maximum and minimum limits on the salary that a player can be expected to earn. Just where the player’s salary will end up within these limits depends on a number of considerations. Union activities have an impact, especially on players whose reservation wage would have been below the league-wide minimum salary resulting from collective bargaining. The most important consideration is the bargaining power of the player relative to that of the owner. Generally, the more close substitutes there are (that is, the easier he is to replace), the more bargaining power the team has, and the salary will be closer to the player’s reservation wage than to his MRP. The more unique are the skills and drawing power of the player (that is, the tougher he is to replace), the more bargaining power the player has, and the closer the salary will be to the player’s MRP.

Just how far apart the reservation wage and MRP limits on a player’s salary will be depends critically on the negotiating rights for players and owners, built into the player market by the rules of the sport. At one extreme is complete free agency, where the ability of players and owners to negotiate with whomever they choose is unrestricted. At the other extreme is the reserve clause system that operated in baseball until 1976. Under the reserve clause … a player can negotiate only with the team owning his contract. Generally speaking, the more freedom there is for players and owners to negotiate, the closer the minimum (reservation wage) and maximum (MRP) limits on a player’s salary will be. However, there can be substantial remaining bargaining room even under unrestricted free agency.

Suppose first that there is unrestricted free agency, with players and owners free to negotiate with whomever they choose. Under such circumstances, if we ignore locational and other nonmonetary considerations, each player will end up signing with the team to which he is most valuable (the team for which the player has the highest MRP). He will be paid a salary that lies between his MRP with that team, and his MRP with the team to which he is second most valuable (the team to which he has the second-highest MRP). The reason for this is that the team to which the player is most valuable can outbid any other team for the player’s services, and still increase its profits by hiring him. But the team can sign the player only if it offers him at least as much as the player can earn elsewhere (the player’s reservation wage), and the most the player can earn elsewhere is clearly his MRP with the team to which he is second most valuable. In a market with completely unrestricted free agency, if we ignore nonmonetary considerations, the grand conclusion is that the highest salary offered to the player will capture at least his second-highest value in the league, and can be up to (but not exceeding) his highest value in the league.

Under a reserve clause system, the team owning a player’s contract has exclusive negotiating rights to the player. Similarly, the college draft gives the team holding a player’s draft rights exclusive rights to negotiate with him (in baseball, for up to six years…). Instead of a competitive market for the player’s services, under a reserve clause system, there is only one bidder for the player’s services. The highest salary the team holding the player’s contract would be willing to pay the player still is the MRP of the player for that team; but under the reserve clause, there is no competitive pressure on the owner of the contract. As a result, the player’s reservation wage is not bid up to his second-highest MRP in the league. Instead, the player’s reservation wage under a reserve clause system is what the player can earn outside of the league, or the league minimum salary, whichever is higher.

Needless to say, for most athletes, the reservation wage calculated in this way lies far below the player’s value to any team in the league. Under the reserve clause system, a player’s wage will end up some place between his reservation wage and his MRP with the team owning his contract. The reserve clause system lowers the value of the player’s reservation wage by eliminating competing offers by other teams, and, unless the player happens to be under contract with the team in the league to which he is most valuable, the upper bargaining limit has been reduced as well. Predictably, the overall effect of a reserve clause system is to lower player salaries relative to what they would earn under free agency.

Put another way, a reserve clause system acts to direct more of the revenue that a player produces to the team owner than to the player. The effect of unrestricted free agency on a league that previously was under a reserve clause system, as in the case of baseball since 1976, would be a bidding up of player salaries to the point where most of the revenue that is linked to the performance of the team ends up in player salaries. Under a reserve clause system, the team can capture a significant fraction of the revenue linked to a team’s performance, as well as revenue that is not so linked.

For both players and owners, the issue of free agency is critical to their economic well-being. While claims that free agency will destroy pro sports thus far are clearly exaggerated, the division of the monopoly rents created by pro sports certainly is at stake. It should come as no surprise, then, that free agency is the central issue in pro team sports collective bargaining. A secondary collective bargaining concern is the league minimum salary, which under a reserve clause system becomes the reservation wage for most players. Under free agency, the league minimum salary is no longer relevant to regulars, but it remains an important bargaining element for other players not yet eligible for free agency.

The point of all this is that the sports labor market has the same fundamental driving forces as any other labor market, that is, the value produced by an employee and his or her bargaining power, with the wage rate ending up somewhere between the reservation wage and the player’s MRP, and with the player’s MRP depending upon the demand by the public for the sport. Interestingly, what goes on in the player market is often portrayed in the press in exactly the opposite fashion, as though it were changes in player salaries that controlled ticket prices and TV revenues.

TICKET PRICE AND PLAYER SALARIES

Owners of sports teams understandably are concerned about escalating salaries for players. After all, they have to pay the bills. But when owners and league commissioners express their opinions about the level of player salaries in public, they like to come on in their self-appointed role of protectors of the fans. Owners are fond of pointing out that if player salaries increase, they (the owners) will be forced to raise ticket prices, or turn to pay-per-view alternatives, in order to obtain the revenues to pay those salaries. The owners’ line would have it that putting a brake on salary increases really is in the interest of fans, who prefer low ticket prices to high ones. This argument seems to be very effective, because fans typically side with the owners in salary disputes with players and in labor negotiations with player unions….

While the owners get effective mileage from this line, it makes very little economic sense. With some rare classic exceptions, such as Phil Wrigley and Tom Yawkey, owners of sports teams are in the business to make money, or at least not lose money. Nobody has to force an owner to raise ticket prices if he or she is fielding a successful team with lots of popular support and a sold-out stadium. Put another way, even if player costs did not rise, one would expect that ticket prices and TV contract values would rise in the face of increasing fan demand. On the other hand, if the team already is having trouble selling tickets, only sheer folly would dictate raising ticket prices.

Given a team’s roster of players, the simple economic fact of life is that the ticket pricing decision by a profit-oriented owner is completely independent of the salaries paid to those players. Profit-oriented ticket-pricing decisions depend solely on the demand by fans for tickets to the team’s games. The demand for the inputs used to produce the games, including players, is derived from this profit-oriented decision, not the other way around. Ticket prices rise when fan demand rises, which in turn increases player MRPs, which spills over into higher salaries for players.

Nowhere is this logic more clearly evident than in the case of baseball in the period just after the beginning of free agency. Free agency acted immediately to raise player salaries…. But fans would not pay more to watch the same players just because they started earning more. The initial effect of free agency was to lower team profits with little impact on ticket prices…. With few exceptions, ticket prices fell in real terms during the very first years of free agency! Indeed, only the Boston Red Sox and New York Yankees had ticket prices in excess of their 1971 levels as late as 1980, four years after free agency. Thus, salaries rose, but ticket prices did not. Ticket prices prior to free agency were already set by owners at levels representing their best guesses as to what would maximize revenue for their teams. Free agency shifted the bargaining power in the direction of players, and player salaries went up. But changes in player salaries per se had no effect on the demand for tickets and no effect on ticket prices.

… This has been a period of rising demand by the public for the major pro team sports. Rising demand led to increases in both ticket prices and TV contract revenues. In turn, the increased demand for pro sports tickets and TV coverage acted to increase the value of skilled players to teams, that is, their MRPs rose. Then, the bargaining process translated the increased value of player skills into higher player salaries. Salaries continued to grow … for all pro sports, spurred on by the growth in team revenues. Under free agency, as in baseball and basketball, more of the increased revenue goes to players than under a reserve clause system … but salaries go up in either case when demand for the sport increases, and, contrary to the argument of owners, they are the effect and not the cause of higher ticket prices.

It might be that the mistaken perception about the link between player salaries and ticket prices comes from a confusion of two different sources of salary escalation. If a team’s salary bill rises because the team has acquired more expensive talent, then the owner can and undoubtedly will raise ticket prices, not because he or she is paying more in salaries, but because he or she is fielding a more attractive team. That was certainly the case with the Yankees in the early days of free agency…. But looking at the league as a whole, the same group of players was around right after free agency as before, so for an average team, the quality of players didn’t change. Consequently, there was no way that the average owner could pass on to fans the increase in salaries that came with free agency; the salary cost increase came directly out of profits, instead.

THE WINNER’S CURSE

Things are not quite as simple as we have been making them, of course—general managers and scouts really do earn the money they are paid. It is no easy task to predict how a player will perform next season, what his contribution to the team will be, and the size of the crowds the team will draw….

We do not pretend to any such skills. Instead, we assume that the market for players “works” in the sense that, on average, bids by skilled general managers and offers by skilled player agents lead to a situation in which players get paid pretty much according to what we have outlined, that is, what they would be worth in their second-best employment in the league.

Well, actually, they may get a little more than that, and maybe even more than their MRPs to the teams that sign them. There is a well-known phenomenon in bidding theory known as “the winner’s curse,” which might be operative in the player markets of the free agency period….

In a sealed-bid auction, say, for league TV rights, the prospective bidders (the networks and cable systems) each evaluate the revenue potential of the TV rights and then, at a specified time, each in effect submits a dollar bid in a sealed envelope. The “lucky” winner is the individual submitting the highest bid. “Lucky” is in quotes, because, by definition, the winning bidder ends up paying more for the right to televise games, and occasionally much more, than any other bidder was willing to offer. Given that all bidders had access to pretty much the same information about the potential market for TV, this suggests that the winner might well have made a mistake in overvaluing the revenue potential of the contract. This is the “winner’s curse”—winning in a sealed-bid auction means the winner might very well have bid too much, and maybe far too much, for the property. In particular, a measure of how much the winner has overbid is the difference between the winner’s bid and the second-highest bid. In the jargon of the field, this difference is what is “left on the table.”

The free agent market in baseball is not as formal as a sealed-bid auction, but there are problems for a general manager in determining how much a player will be worth to his team and in guessing how much other teams will be willing to offer the player. Ideally, a general manager would like to pay any player just $1 more than the player’s best offer anywhere else, but this option is only available in cases where the team has “right of first refusal,” that is, the right to match any outside offer.

With lots of teams out there operating in the free agent market (and assuming no collusion), there will be vigorous competitive bidding for players. Clearly, teams underestimating the MRPs of free agents will typically not be the teams signing them; instead, there is better chance that the “winners” in the free agent market will be teams overestimating player MRPs, and these are the teams stuck with the “winner’s curse.” And, in turn, the presence of the winner’s curse means that players get paid on average even more than their value in their second-best employment opportunities in the league. This cannot be too surprising. Sportswriters, each year, are fond of rubbing owners’ noses in the winner’s curse by pointing out how overpaid many (some would say most) free agents are, relative to their subsequent performance.

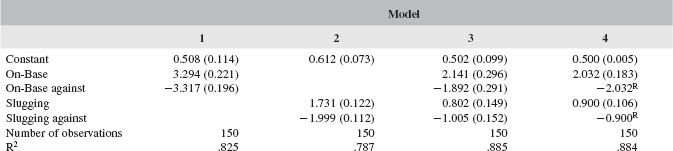

SALARY DETERMINATION IN BASEBALL

Assuming that the baseball player market operates to generate salary offers that correlate roughly with player MRPs, we can identify factors that can be said to “determine” baseball player salaries in the sense that these factors are highly correlated with market-determined salary levels, and thus do a good job of predicting the level of baseball player salaries…. The equation is a “best fit” model of salary determination in the sense that (1) it explains a large portion of the total variation in player salaries, and (2) adding other factors to the equation would not significantly improve its predictive power. Models … are used both by players and by owners in justifying their positions on salary demands in the baseball salary arbitration process….

… The clear conclusion is that income inequality in the rest of the U.S. economy, although high relative to other countries, pales in comparison to the inequality in recent years in baseball salaries.

It is also clear that baseball salaries have become less equally distributed over time, and skewed toward the top of the salary scale, with a noticeable jump between the reserve clause and free agency periods… Overall, from the baseball salary data, we can conclude that while all players benefited from free agency, a disproportionate share of the benefits went to the top players, who were the big gainers from free agency. Players at the lower end of the distribution, still held captive by united mobility for their first six years, lost ground relative to their star teammates.

….

Notes

1. Quoted in Rick Telander, The Hundred Yard Lie, New York: Simon & Schuster 1989, at 41.

THE SPORTS BUSINESS AS A LABOR MARKET LABORATORY

Lawrence M. Kahn

Professional sports offers a unique opportunity for labor market research. There is no research setting other than sports where we know the name, face, and life history of every production worker and supervisor in the industry. Total compensation packages and performance statistics for each individual are widely available, and we have a complete data set of worker–employer matches over the career of each production worker and supervisor in the industry. These statistics are much more detailed and accurate than typical microdata samples such as the Census or the Current Population Survey. Moreover, professional sports leagues have experienced major changes in labor market rules and structure—like the advent of new leagues or rules about free agency—creating interesting natural experiments that offer opportunities for analysis.

….

Of course, it is wise to be hesitant before generalizing from the results of sports research to the population as a whole. The four major team sports employ a total of 3,000 to 4,000 athletes who … earned … far above the … median earnings of full-time, full-year equivalent workers…. But at a minimum, sports labor markets can be seen as a laboratory for observing whether economic propositions at least have a chance of being true….

MONOPSONY AND PLAYER SALARIES

Sports owners are a small and interconnected group, which suggests that they have some ability to band together and act as monopsonists in paying players. The result is that player pay is held below marginal revenue product. I discuss three sources of evidence on monopsony in sports: evidence from the rise and fall of rival leagues, evidence from changes in rules about player free agency, and studies comparing the marginal revenue product of players with their pay. Sports owners have often had monopsony power over players in the sense that in many instances players have the option of negotiating only with one team. Here, salaries are determined by individual team–player bargaining in which marginal revenue product, and the outside options available to teams and players, will affect the outcome. Rules changes and the rise and fall of rival leagues have their effects by changing players’ and teams’ outside options.

RIVAL LEAGUES

There have been two time periods in which rival leagues posed a substantial threat to existing professional sports. The first is the period from 1876 to 1920, when there was a scramble of professional baseball leagues forming, merging, and dissolving. The second is the period from the late 1960s into the early 1980s, when new leagues were born in basketball, hockey, and football.

… Baseball is the oldest major league sport in the United States, beginning with the birth of the National League in 1876. In this early period, there was competition for player services from other baseball leagues. To protect itself against the competition of rival leagues and improve the team owners’ balance sheets, the National League introduced the “reserve clause” in 1879, which meant that players were bound to the team that originally acquired the rights to contract with them. Owners now had additional monopsony power over players, and player salaries dropped.

However, the lower salaries may have contributed to the birth of a new league in 1882, the American Association…. Average nominal National League salaries rose from $1,375 in 1882 to $3,500 in 1891…

This increase in salaries is not conclusive evidence that monopsony power of owners decreased; after all, salaries could have risen for other reasons, like the growth of baseball’s popularity. However, in 1891, four of the American Association teams were absorbed into the National League, and five dissolved AA franchises were bought out by the survivors…. [which coincided with] an abrupt, massive decline in National League player salaries starting in the first season of the merger: player pay fell from $3,500 in 1891 (before the merger) to $2,400 in 1892 to $1,800 in 1893. This pay cut was accomplished as the outcome of the National League owners announcement in 1893 of a new salary policy: the maximum pay for a player was to be $2,400. Indeed, some teams imposed lower caps: eight top players on the Philadelphia Phillies who were all paid more than $3,000 in 1892 found that they were all paid exactly $1,800 in 1893. The sharp decline in player salaries does not appear to reflect a major decline in the demand for baseball entertainment, as attendance climbed through the 1895 season.

The success of the National League waned somewhat in the late 1890s, partly due to a lack of competitive balance, but the baseball market was growing. A new rival league, the American League, began in 1901 with eight teams. It successfully lured many star players from the older league and actually outdrew it in attendance in 1902 by 2.2 million to 1.7 million. In response, the National League attempted to have its reserve clause enforced by state courts to prevent players from jumping leagues; however, because state courts have no jurisdiction for player movements outside a given state, it was ultimately unsuccessful in this effort.

A familiar pattern then emerges. The huge success of the American League brought with it a dramatic rise in player salaries. In fact the salary increase appears to begin in 1900, perhaps reflecting anticipation of the new league. The two leagues merged during the 1903 season, at the end of which the first World Series was played. Then in 1903, salaries in Major League Baseball fell immediately by about 15 percent…. Again, this decline does not seem to reflect any fall in baseball’s popularity that year.

Major League Baseball prospered for the rest of the first decade of the twentieth century, with player costs under control and attendance on the rise. However, attendance fell beginning in 1910, and owners kept a tight lid on salaries. Player discontent resulted in the formation of a union, the Fraternity of Professional Baseball Players of America, at the end of the 1912 season. The owners were under no legal obligation to bargain with a union and reacted to it with some hostility.

This dissatisfaction among players helped pave the way for the Federal League, which was able to recruit to long-term contracts several well-known Major League ballplayers beginning in 1913. The pay cycle began again. While the Federal League was in existence from 1913 through 1915, many players jumped leagues, and major league salaries went from about $3,000 in 1913 to $5,000 in 1915. After the 1915 season, most of the Federal League’s owners were “bought out” in December 1915 by the major leagues, and nominal salaries plummeted back to $4,000 by 1917, a fall that was even larger in real terms due to the inflation of the World War I period.

The Federal League owners who were not part of the settlement pursued an antitrust suit against the settling parties for creating a monopoly; however, this suit was lost in 1922, when the U.S. Supreme Court declared that baseball was not a business.1 This decision began baseball’s antitrust exemption, which was upheld several times, most notably in an unsuccessful attempt by a player named Curt Flood to become a free agent in 1969.2 While Flood lost his case, it may have set the stage for baseball players’ ultimately successful quest for free agency. However, this goal was not achieved through the antitrust laws; in fact, baseball’s exemption lasted with respect to player relations until legislation ending it was passed in 1998. Rather, collective bargaining brought free agency to baseball, as discussed below.

The early experiences of Major League Baseball provide some compelling evidence for the potential impact of monopsony in this labor market. However, the comparisons just discussed all concern baseball, and thus have no real control group. In the modern period, we can use salaries in some sports as control groups for other sports.

From the late 1960s into the 1970s, highly credible rival leagues were born in basketball and hockey. The American Basketball Association (ABA), which lasted from 1967 to 1976, was able to field some very good teams. In 1976, four of its teams were absorbed into the NBA, and these all made the NBA playoffs in several seasons after the merger. The NBA Players Association (NBPA) challenged the merger on antitrust grounds, but then withdrew its lawsuit as the result of a settlement which granted free agency rights to NBA players. The World Hockey Association (WHA), which lasted from 1971 to 1979, also had several excellent teams which were absorbed into the NHL starting in 1979.

The rise and fall of these two rival leagues offer another opportunity to test how monopsony might affect salaries since the other two major team sports—baseball and football—had no such competition in their labor markets until the advent of free agency in baseball in 1976 and the birth of the United States Football League (USFL) in 1982.

… In 1967, there were no rival leagues in baseball, football, or hockey, and the ABA was just getting started. Further, there was no free agency, and players unions had not yet negotiated their first agreements. Thus, the 1967 salaries can be viewed as representing common initial conditions with respect to negotiating rules, although not necessarily with respect to demand conditions.*

By 1970 and 1972, the ABA had been in existence for several years, and NBA players rapidly became the highest paid of the major team sports. The World Hockey Association started in 1971, and by 1972, NHL players outearned football and baseball players by similar margins. These upward movements in the relative salaries of basketball and hockey players, while consistent with effects of the new competition, need to be judged against the changing popularity of these two sports. For example, in the NBA, total attendance rose by 120 percent between 1966–67 and 1971–72, while television revenues went from $1.5 million to $5.5 million during the same period, rises that were much, much greater than the increases for football or baseball during this time…. The shock of higher salaries may also have spurred the teams to market themselves better. Moreover, NBA salaries as a percentage of gross basketball revenues rose from 30 percent in 1967 to 66 percent in 1972, which suggests a structural shift in salary determination that goes beyond a rise in revenues. In the NHL, attendance growth was actually much faster in the five years before the birth of the WHA (135 percent) than while the WHA was in business (7 percent). Thus, the acceleration of NHL salaries after 1971 is telling indeed.

There is one more important example of the impact of a rival league on player salaries, the United States Football League (USFL). Like some of the baseball experiences earlier in the century, the USFL was born out of labor strife in the established league; in this case, it was a seven-week NFL strike in 1982, in which the players had failed to gain any significant ground in their fight for free agency or a share of revenues. From 1982 to 1985, the USFL posed a challenge to the established NFL. The USFL had strong financial backing from such owners as Donald Trump; many NFL players switched leagues; and the USFL was able to sign some high-profile college players such as Anthony Carter and Herschel Walker. However, poor television ratings for the USFL ultimately signaled its demise.

The pattern of football player salaries during the USFL years follows that set by the example of other rival leagues. Real salary increases for NFL players averaged 4 percent per year from 1977–1982, before the USFL, and 5 percent per year from 1985–1989, just after the USFL. In between, real player salary increases were 20 percent per year from 1982–1985. Changes in the popularity of football do not seem sufficient to explain the explosion of salaries during the USFL years. From 1977 to 1981, NFL attendance rose 23 percent, but attendance was actually 2 percent lower in 1985 than in 1981; further, NFL television revenues rose by similar rates before and during the USFL years. Overall, NFL salaries during the USFL period were much higher than could have been predicted on the basis of revenues during that time.†

If one uses other sports as a control group for the experience of football salaries in the USFL years, the same lesson emerges. The salary growth for football players from 1982 to 1985 was 8–10 percentage points per year higher than baseball and basketball, and 17 percentage points per year higher than for hockey players. However, during the 1981–85 period, attendance grew 5 percent in baseball, 11 percent in the NBA, 11 percent in the NHL, and, as noted, fell 2 percent in the NFL; television revenues grew 211 percent in baseball and 35 percent in the NBA, compared to 29 percent in the NFL. The faster growth of NFL salaries during the 1982–85 period despite worse attendance and television revenue increases again suggests the importance of the USFL.

FREE AGENCY

Until 1976, players in each of the four major sports were bound by the reserve clause to remain with their original team, unless that team decided to trade or sell them to another team. They were not allowed to become free agents, who could sell their services to any team.

The path toward free agency started in baseball. The Major League Baseball Players Association (MLBPA) was started in 1952, but it didn’t become a modern union until the former United Steelworkers negotiator, Marvin Miller, took over in 1966. The MLBPA achieved a collective bargaining agreement in 1968, and in 1970 the National Labor Relations Board ordered the parties to use outside arbitrators for resolving grievances. In a farsighted decision, Miller obtained management’s agreement to incorporate the standard player contract, which included the reserve clause, into the collective bargaining agreement. This meant that grievances about the interpretation of this clause were a proper subject for arbitration. In December 1975, an arbitrator ruled that the reserve clause meant that the team could reserve a player for only one year beyond the expiration of any current contract. With the reserve clause in place, almost all teams signed players exclusively to one-year contracts, and so this ruling would have freed virtually all of the veteran players after the 1976 season. The teams, threatened with this possibility, were thus moved to negotiate a formal system of free agency with the union in 1976, calling for free agency (with some relatively minor compensation to any team losing a free agent) for players with at least six years of Major League Baseball service. This provision remains basically in place. In 1994, about 33 percent of players had at least six years’ service. [Ed. Note: In 2009, 308 of the 1,293 players on MLB teams’ 40-man rosters, voluntarily retired lists and disabled lists had at least 6 years of service.]

The rise of free agency in the 1976–77 period had a powerful impact on the salaries of baseball players. The average real increase in baseball salaries was from 0–2 percent per year from 1973–75. In 1976 the average real salary increase was almost 10 percent; in 1977, the first year under the new collective bargaining agreement, 38 percent (!); in 1978, 22 percent, before falling back into single digits growth in 1979. Moreover, baseball salaries as a percentage of team revenues rose from 17.6 percent in 1974 to 20.5 percent in 1977 to 41.1 percent in 1982, further suggesting that free agency has had a structural effect on baseball salary determination.* A final point to note about baseball salary determination is that in a series of grievance arbitration decisions in the 1980s, the owners were found guilty of colluding by not making offers to free agents. This reassertion of cartel wage-setting behavior appeared to be successful in restraining salary growth. Real annual growth in baseball salaries fell from 11 percent in the 1982–85 time period to 3 percent from 1985–87. Moreover, salaries as a percent of revenues fell from about 40 percent in 1985 to 32 percent in 1989 during the collusion period. In 1989, arbitrators levied a $280 million back pay penalty on the owners to be paid out over the 1989–91 period as compensation for the losses imposed by collusion, and salaries as a percent of revenue bounced back to 43 percent by 1991. The collusion episode provides a further illustration of the potential impact of monopsony on salaries.

Basketball players also won free agency in 1976, but by a different route, through the settlement of the players’ antitrust suit challenging the ABA–NBA merger. As a result, free agency in the NBA came on the heels of the ABA–NBA salary war period of 1967–76. Possibly as a result, average salaries grew more slowly in the NBA in the 1977–82 period than in football or baseball, a comparison which does not suggest a major impact of free agency in the NBA in addition to the impact of competition from the ABA. On the other hand, NBA salaries amounted to about 70 percent of revenue in 1977 and “nearly three quarters” in 1983, suggesting some further increase in basketball players’ relative power after the coming of free agency even without the benefit of an alternative league.3 Finally, basketball imposed a salary cap in 1983, and salaries did indeed decelerate after 1985. However, there were many exceptions to the salary cap, and it may ultimately have had little effect on salaries during this period.

EVIDENCE OF THE DEGREE OF MONOPSONISTIC EXPLOITATION

To this point, the argument has relied on presenting abrupt shifts in salaries that are difficult to explain without appealing to the theory of monopsony. An alternative mode of research on salary determination is to compare estimates of players’ marginal revenue products to salaries, and in this way to approximate the degree of monopsonistic exploitation….

… Scully found that star players in 1987 were paid 29–45 percent of marginal revenue product; even though this was the height of the collusion period, the percentage was still much higher than the 15 percent he found for the reserve clause days.4 Zimbalist’s approach compares the players eligible and not eligible for free agency.5 In 1989, for those players with less than three years service, and thus not eligible for salary arbitration or free agency, the ratio of salary to marginal revenue product was just .38 times what it was for those eligible for salary arbitration only and .18 times that for those eligible for free agency.†

These measures of monopsonistic exploitation must be interpreted cautiously since (as noted by the authors of the studies) they do not control for a player’s effects on revenue other than through his own playing statistics’ effects on winning.* However, taken as a whole, this line of research produces additional evidence that making the labor market more competitive leads to higher salaries than would be the case under monopsony. Nonetheless, during the 1980s there still appeared to be widespread monopsonistic exploitation in baseball, and research from this period also showed similar results for basketball.

[Ed. Note: The author’s discussion of the Coase theorem and sports and racial discrimination is omitted. See Chapter 18 for a discussion of the latter topic.]

….

INCENTIVES, SUPERVISION, AND PERFORMANCE

Some of the most intriguing evidence on the links from incentives to performance comes from sports that have not been much discussed to this point, like golf and marathon running. Ehrenberg and Bognanno used data from the 1984 U.S.-based Professional Golf Association (PGA) and 1987 European PGA tours to estimate the impact of incentives on player performance.6 Because the prize structure of a given tournament is known in advance, one can compute the dollar gain to improving one’s finishing position in a tournament. Ehrenberg and Bognanno found that a greater dollar gain to a better finish had a statistically significant favorable effect on a player’s performance, controlling for the player’s ability, his opponents’ ability, and the difficulty of the course. In addition, golfers appear to perform better when it matters more, particularly in the later rounds of a tournament. Finally, golfers’ labor supply, as measured by their propensity to enter a given tournament, is positively affected by the expected gain to participating, implying an upward-sloping labor supply schedule.† However, a more recent replication study, using 1992 PGA data, found that monetary incentives had small and statistically insignificant effects on player performance and that results were sensitive with respect to who rated the weather that prevailed during a tournament.7

The framework devised by Ehrenberg and Bognanno has been used to examine the incentive impact of prize money in two additional sports: marathon running and auto racing.8 In auto racing, Becker and Huselid found that larger monetary rewards to better finishes lowered individual racers’ finishing times and raised the incidence of accidents, presumably due to a greater effort to go fast.9 In marathon races, Frick found that better prize money and performance bonuses for setting records lowered racing times.10

In the major team sports that have been the primary focus of this paper, free agency has brought with it an increased incidence of long-term contracts, a finding Lehn argued was consistent with wealth effects, as players in essence buy long-term income insurance.11 He noted that as the incidence of long-term contracts went from virtually zero during the days of the reserve clause to 42 percent of baseball players with at least two years pay guaranteed as of 1980, the share of baseball players who spent time on the disabled list rose from an average of 14.8 percent from 1974 to 1976 (before free agency) up to 20.8 percent from 1977 to 1980 (the early years of free agency). Lehn surmised that this increase was a moral hazard response by players on guaranteed long-term contract. In this instance, moral hazard refers to a player’s impact on the decision to go or stay on injured reserve.

To perform a sharper test of this hypothesis, he compared players in 1980 who had long-term contracts of three years or more with those who had short-term contracts of two years or less. Prior to signing these contracts, those with long-term contracts were almost two years younger and had 2.2 days per season less disability than those who signed short-term contracts. Thus, those with long-term contracts do not appear to be an especially injury-prone group. Nonetheless, after signing their agreements, those with long-term contracts averaged 12.6 disabled days per season, compared to only 5.2 days for those with 0–2 years. Lehn confirms in a regression setting that this effect is highly statistically significant.12 The finding is strongly suggestive of a moral hazard effect, although one cannot completely rule out that players who had private information that they were fragile were more likely to sign long-term contracts, in which case the results could also reflect adverse selection.

Of course, one way for a team to reduce the moral hazard response is to reward players for not being injured. Lehn notes that 38 out of 155 players with contracts of three or more years, or about 25 percent, had incentive clauses in their contracts.13 These clauses sometimes rewarded either being available to play for most of the season or postseason awards won (such awards typically require being active for all or most of the year). Before signing such long-term contracts, those who ended up with incentive bonuses had virtually identical average propensities to be injured as those without such incentive bonuses. However, after signing, the injured time of players without incentive bonuses was 2.4 times that of those with bonuses. Again, a strong moral hazard response is suggested, although as before, we cannot rule out the adverse selection possibility that players who suspected that they were likely to be fragile have turned down the opportunity to sign a contract with an incentive bonus.

Hiring better quality management is an alternative route, along with contract incentives, for eliciting desired performance levels. In a study of the impact of baseball managers, I estimated the effect of better managers on team and individual player performance.14 Managerial quality was measured by first running a 1987 regression with manager salary as the dependent variable and managerial experience, career winning percentage, and a National League dummy variable as the explanatory variables. Then, using the coefficients from the regression, I plugged in each manager’s actual experience and winning percentage to get a predicted salary level. I then calculated that during the 1969–86 period, hiring a better quality manager significantly raised the team’s winning percentage relative to its past level—even if one also controls for team scoring and runs allowed, suggesting that good managers win the close games. The effect of good managers was even larger when I didn’t control for offense and defense. The latter effect could indicate that better managers are superior judges of talent, or motivate their players, and thus indirectly contribute to offense and defense.

I also studied individual player performance relative to established career levels when the team was taken over by a new manager. The better the quality of the new manager, the better a player’s future performance relative to his past performance. In related calculations, I found an increase in managerial quality more than pays for itself based on Scully’s results for the effect of winning on revenue.15 Because of this, one might have expected the salaries of highly talented managers to be bid up. The fact that they weren’t as measured in the 1987 salary data used in this study may be further indirect evidence of collusion between baseball owners during this time period.

FINAL THOUGHTS

Labor issues in sports may seem distant from the rest of the economy, since they often seem to pit millionaire players against billionaire owners. But while it would be unwise to extrapolate too strongly from the labor market experience of sports, evidence on a particular labor market should not be discounted just because the market has a high profile, either. The strong evidence for monopsony in sports has some parallels to a similar effect that has been found among groups such as public school teachers, nurses, and university professors.16 The evidence from these areas suggests that the phenomenon of employer monopsony power could be more widespread than is commonly acknowledged by economists. The presence of customer discrimination in sports reminds us that there are many sectors in the economy with producer–customer contact where discrimination could persist. The results on player performance suggest that athletes are motivated by similar forces that affect workers in general.

While this paper has concentrated on sports in North America, many of the same economic issues arise in the sports industry elsewhere. Professional soccer leagues in Europe are tremendously lucrative and also must be concerned with player movement and competitive balance…. In fact, European soccer draws more TV revenue than the NBA, Major League Baseball, or the NHL. The promotion and demotion of individual teams to and from a… European superleague involving teams from several countries raise fascinating questions about the role of competitive balance.

….

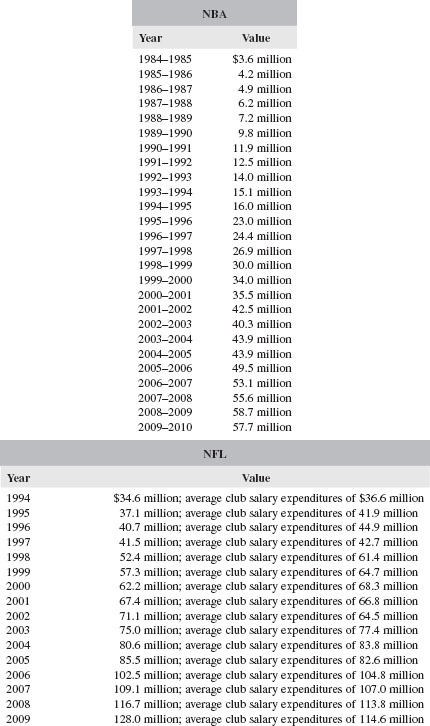

(See Table 3 for salary cap growth in the NBA and NFL.)

Notes

1. Federal Baseball Club of Baltimore, Inc. vs. National League of Baseball Clubs, et al., 259 U.S. 200 (1922).

2. Flood vs. Kuhn, 407 U.S. 258 (1972).

3. Staudohar, Paul D. 1996. Playing for Dollars: Labor Relations and the Sports Business. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, at 108.

4. Scully, Gerald W. 1989. The Business of Major League Baseball. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

5. Zimbalist, Andrew. 1992. Baseball and Billions. New York: Basic Books.

6. Ehrenberg, Ronald G. and Michael L. Bognanno. 1990. “Do Tournaments Have Incentive Effects?” Journal of Political Economy. 98:6, pp. 1307–1324; Ehrenberg, Ronald G. and Michael L. Bognanno. 1990. “The Incentive Effects of Tournaments Revisited: Evidence from the European PGA Tour.” Industrial & Labor Relations Review. 43:3, pp. 74–88.

7. Orszag, Jonathan M. 1994. “A New Look at Incentive Effects and Golf Tournaments.” Economics Letters. 46:1, pp. 77–88.

8. Ehrenberg, Ronald G. and Michael L. Bognanno. 1990. “Do Tournaments Have Incentive Effects?” Journal of Political Economy. 98:6, pp. 1307–1324; Ehrenberg, Ronald G. and Michael L. Bognanno. 1990. “The Incentive Effects of Tournaments Revisited: Evidence from the European PGA Tour.” Industrial & Labor Relations Review. 43:3, pp. 74–88.

9. Becker, Brian E. and Mark A. Huselid. 1992. “The Incentive Effects of Tournament Compensation Systems.” Administrative Science Quarterly. 37:2, pp. 336–50.

10. Frick, Bernd. 1998. “Lohn und Leistung im Professionellen Sport: Das Beispiel Stadt-Marathon.” Konjunkturpolitik. 44:2, pp. 114–40.

11. Lehn, Kenneth, 1990. “Property Rights, Risk Sharing and Player Disability in Major League Baseball,” in Sportometrics. B. Goff and R. Tollison, eds. College Station, Texas: Texas A&M Press, pp. 35–58.

12. Id.

13. Id.

14. Kahn, Lawrence M. 1993. “Managerial Quality, Team Success and Individual Player Performance in Major League Baseball.” Industrial & Labor Relations Review. 46:3, pp. 531–47.

15. Scully, Gerald W. 1989. The Business of Major League Baseball. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

16. Ehrenberg, Ronald G. and Robert S. Smith, 2000. Modern Labor Economics, 7th ed. Reading, Mass.: Addison-Wesley.

Table 3 Salary Cap Growth in NBA and NFL

Source: ESPN.com, NFLPA documents, additional data on file from authors.

DOES ONE SIMPLY NEED TO SCORE TO SCORE?

David J. Berri, Stacey L. Brook, and Martin B. Schmidt

“Players must not only have objectives, but know the correct way to achieve them. But how do the players know the correct way to achieve their objectives? The instrumental rationality answer is that, even though the actors may initially have diverse and erroneous models, the informational feedback process and arbitraging actors will correct initially incorrect models, punish deviant behavior, and lead surviving players to correct models.” Douglass North (1994)

INTRODUCTION

The writing of Douglass North lays forth the role instrumental rationality plays in the workings of an efficient market. Given the requirements outlined above and the prevalence of imperfectly competitive industries, one may not expect many markets to be characterized as efficient. A potential exception is the professional sports industry. Unlike most industries, professional team sports have an abundance of information on individual workers and stark consequences for failure. Failure in sports is not only met with a loss of revenues and employment, but public derision via various media outlets. Given the severity of consequences and abundance of information, it is not surprising that economists expect economic actors in professional team sports to follow the dictates of instrumental rationality.

Despite this expectation, there is some research that suggests that instrumental rationality does not always characterize decision-making in professional sports. In baseball we have the “Moneyball” story [see Lewis (2003) and Hakes & Sauer (2006)], or the argument that on-base percentage was under-valued by decision-makers in Major League Baseball. Michael Lewis (2003) told this story primarily with anecdotal evidence in his best-selling book. Hakes and Sauer (2006) confirmed that the empirical evidence was at one point consistent with the Moneyball story. Historically decision-makers in baseball did undervalue on-base percentage.

Turning to the National Football League we see the work of Romer (2006). Romer investigated how often NFL head coaches choose to “go for it” on fourth down and found that coaches were far too conservative. Going for it more frequently would increase the probability that coaches would win games; hence, the actions of the head coaches actually ran counter to their stated objective.

Staying in the NFL we see the work of Massey and Thaler (2006). This work offered evidence of inefficiency in the amateur draft of the National Football League. Specifically, high draft choices were consistently over-valued, in a fashion the authors argue is inconsistent with the precepts of rational expectations.

With respect to professional basketball—the subject of this study—we have the work of Staw and Hoang (1995) and Camerer and Weber (1999). Each of these authors examined the escalation of commitment in the NBA, defined by Camerer and Weber as follows:

“when people or organizations who have committed resources to a project are inclined to ‘throw good money after bad’ and maintain or increase their commitment to a project, even when its marginal costs exceed marginal benefits.” [Camerer and Weber: 59–60]

With respect to the NBA, Staw and Hoang (1995) and Camerer and Weber (1999) investigated the impact a player’s draft position has on playing time. Both of these sets of authors offer evidence that, after controlling for the prior performance of the player, where a player was chosen in the draft still impacts the amount of playing time the player receives after the first two years of the player’s career. Such a finding suggests that NBA decision-makers are slow to adopt new information, maintaining an assessment of a player when the available evidence suggests that the initial perspective is incorrect.

The purpose of this present inquiry is twofold. First we wish to re-examine several pieces of evidence previously presented in the literature. As we will demonstrate, much of this research suggests that decision makers in the National Basketball Association (NBA)—as suggested by the study of escalation of commitment—do not process information efficiently. Our review will be followed by two empirical models. The first will update Berri and Schmidt (2002), which examined the coaches’ voting for the All-Rookie team in the NBA. A second model will ascertain the relationship between player salary and various measures of player productivity. Each of these models—previously described in less detail in The Wages of Wins [Berri, Schmidt, and Brook (2006)]1—will shed light upon the extent information is utilized efficiently in the evaluation of players in the NBA.

THE LESSONS LEARNED

Our story begins with a review of the lessons the current body of literature teaches about the economics of professional basketball. We begin this list of lessons with the story told by a number of published works examining racial discrimination in professional basketball.

Lesson One: Points Scored Dominates the Evaluation of Player Productivity in the NBA

… Berri (2006) surveyed twelve studies examining racial discrimination in the NBA.7 … Given that some papers offered more than one model, Berri’s survey examined fourteen specific models.

Surprisingly, most aspects of player productivity were not consistently linked statistically to the decision-variable examined. In fact, the only factor consistently found to be correlated with player evaluation in the NBA is points scored. In fourteen of the fifteen models examined, points scored was found to be both the expected sign and statistically significant.8 Of the other factors employed by researchers, only total rebounds and blocked shots were statistically significant more often than not.9 The significance of assists was evenly split,10 while field goal percentage was significant in only four of the nine models where it was employed. Every other factor was not significant more than once. In sum, player evaluation in the NBA appears to be driven by points scored and, perhaps, total rebounds, blocked shots, and assists.

Such results tell two important stories. The first centers on the importance of scoring in the NBA. Virtually every study employed a player’s total points or points scored per game.11 One should note, though, that a player’s accumulation of points is dependent on the playing time the player receives and the number of shots taken. Simply staying on the floor and taking a large number of field goal and free throw attempts can lead to the accumulation of lofty point totals. Clearly, efficiency in utilizing shot attempts would also be an indicator of a player’s worth to a basketball team. As noted, though, field goal percentage was not statistically significant in the majority of studies where this factor was considered.12 In other words, a player who scores points can expect to receive a higher salary. Evidence that scoring needs to be achieved via efficient shooting is not quite as clear.

The second story told is about the insignificance of many other facets of a player’s performance. Players do not appear to be evaluated in terms of free throw percentage, steals, or personal fouls. Turnovers, a factor Berri (2009, in press) has identified as significant in determining wins in the NBA, has only been included once and was found to be insignificant. Given the ambiguous results uncovered with respect to everything else besides a player’s points scored per game, these results suggest that a player interested in maximizing salary, draft position, employment tenure, and playing time should primarily focus upon taking as many shots as a coach allows.

Lesson Two: Player Productivity on the Court Creates Team Wins

The literature on team-wins production, though, suggests that wins are about more than points scored per game. We begin this discussion with an obvious statement. The actions of the players on the court determine the outcome of the contest observed. The key to understanding the individual contribution to team wins, though, requires a bit more investigation.

The seminal work of Gerald Scully (1974) provides a guide to those seeking to uncover the relationship between player action and team wins in professional team sports. Scully, in an effort to measure the marginal product of a baseball player, offered a model connecting team wins to player statistics.13

Berri (in press) recently adopted the Scully approach in developing a simple measure of marginal product in professional basketball. This model,14 indicates that points scored, rebounds, steals, turnovers, and field goal attempts each had an equal impact on team wins. Although points scored are important in determining outcomes, factors associated with acquiring possession of the ball also significantly impact a team’s on-court success.

The review of the literature on racial discrimination revealed the importance of points scored, as well as rebounds, blocked shots, and assists. This list of factors can be thought of as highlight variables, since any collection of highlights from the NBA will consists of players scoring points, collecting rebounds, blocking shots, or making creative passes. Although these highlight variables are often correlated with player compensation, wins in the NBA are about more than these highlight factors.

Lesson Three: Team Wins Drive Team Revenue

Perhaps team wins, though, are not the objective of NBA organizations. Such a possibility was considered in the work of Berri, Schmidt, and Brook (2004). These authors examined the importance of winning games as opposed to the star power of a team’s roster. Specifically, a team’s gate revenue was regressed upon team wins, all-star votes received, and a collection of additional explanatory variables. The results indicate that it is wins, not star power, which primarily determines a team’s financial success.

Two anecdotes support this empirical finding. The team who led the league in attendance during the 2003–04 regular season was the Detroit Pistons. Although the Pistons eventually won the 2004 NBA championship, Detroit achieved its success via team defense. Only five teams scored fewer points than the Pistons. Detroit’s regular season scoring leader, Richard Hamilton, ranked only 27th in the league with 17.6 points per game.15

The story of Allen Iverson and the Philadelphia 76ers further supports the low economic value of star power and scoring for an NBA team. In 2005–06 the 76ers sold out every game on the road.16 At home, though, the 76ers were one of only three teams to play before crowds that were less than 80 percent of their home arena’s capacity. Although the 76ers employed a major star and scorer in Allen Iverson, the team’s sub-0.500 record resulted in below average home crowds.

Lesson Four: Team Payroll is not Highly Correlated with Team Wins

Given the abundance of information on player productivity and the expectation that player productivity is linked to player salary, one might expect payroll and wins to be correlated. Stefan Szymanski (2003) investigated the link between wages and team success in a variety of professional team sports, including the NBA. Although the relationship between relative payroll and wins was found to be statistically significant, only 16% of winning percentage in the NBA was explained by relative payroll.17

A similar result was reported by Berri and Jewell (2004). Specifically, a model was offered that looked at the importance of adding payroll, via the addition and subtraction of players, and simply giving existing players an increase in salary. Of these two factors, only adding payroll was statistically significant. Of interest, though, was that the explanatory power of the model employed was only 6%. Much of the changes in team success upon the court in the NBA are not explained by alterations to a team’s level of talent, as measured by additions to team payroll.

Lesson Five: Player Performance is Relatively Consistent Across Time

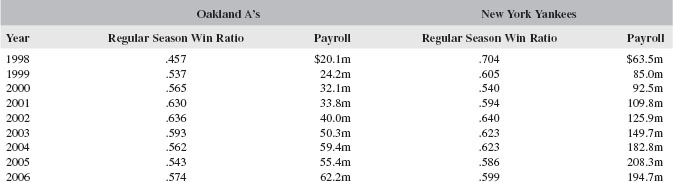

The lack of a strong relationship between wins and payroll is also observed in Major League Baseball and the National Football League. Berri, Schmidt, and Brook (2006) report that relative payroll in baseball only explains 18% of team wins in MLB from 1988 to 2006. If we look at the NFL from 2000 to 2005 we find that only 1% of wins are explained by relative payroll.18

The inability of payroll to explain wins can at least partially be explained when we look at how difficult it is to project performance in both football and baseball. Berri (2007) and Berri, Schmidt, and Brook (2006) present evidence that performance in football is quite difficult to predict. Summary measures such as the NFL’s quarterback rating, metrics like QB Score, Net Points Per Play, and Wins Per Play—introduced in Berri, Schmidt, and Brook (2006)—and various metrics reported by FootballOutsiders.com tend to be quite inconsistent across time. Less than 20% of what a quarterback does in a current season, measured via any of the above listed metrics, is explained by what a quarterback did last season. A similar result is reported for running backs by Berri (2007).

When we look at baseball we also see a problem with projecting performance. Berri, Schmidt, and Brook (2006) report that less than 40% of what a hitter does in the current season can be explained by what he did last season.19 These results suggest that even if teams were perfectly rational, the inability to project performance is going to result in a weak link between pay and wins.