CHAPTER ELEVEN

INTRODUCTION

Whether for a prospective sale, a bankruptcy, or leveraging debt, at various times it is necessary to place an accurate value on a sports franchise. As this chapter reveals, valuation of professional sports franchises is no simple task. As evidenced by the numerous sales of both established and expansion teams in the four major North American sports leagues and clubs in many European soccer leagues for seemingly ever-increasing amounts of money, the market for professional sports franchises continues to be robust. Although the study of firm and asset valuation has been a common area of research in finance, there has been little application of these principles to professional sports franchises.

Valuation of professional sports franchises is much different than valuations of most other assets. This is likely because of the idiosyncratic nature of sports franchises, which are somewhat comparable to the valuation of art in that, ultimately, beauty is in the eye of the beholder. Thus, there is significant volatility in the marketplace. The total financial return to owners of professional sports franchises is determined by calculating a team’s profitability and capital appreciation. Although the franchise’s ability to earn a profit and its likelihood of increasing in value in the long term play important roles in determining a team’s present value, numerous other factors impact franchise value.

The nature and quality of a team’s facility arrangement is one factor. Given the increase in the number of new, revenue-generating facilities in the last 15 to 20 years, it is important to gauge the impact that these stadia and arenas have on franchise values. The building boom that has occurred since the late 1980s has resulted in new or renovated stadia for most of the teams in the four major North American sports leagues. Globally, European soccer clubs are still in the early stages of the stadium construction era. The presence of a playing facility with a lease arrangement that allows the team to generate and retain significant revenues from luxury boxes, club seats, signage, naming rights, concessions, parking, and outside events at a low cost (i.e., little rent) will drive franchise values upward. The absence of such an agreement will have the opposite effect.

In addition, a team’s media contracts impact its value. The size of the league-wide television contract provides guaranteed revenues to each team and indicates the nationwide popularity of the sport. However, the size of the local television contract secured by a club varies greatly. The local television contract provides a team with revenue that is largely unshared and is an indicator of a team’s popularity in its home market. Increased involvement of teams in the ownership of regional sports networks not only provides the opportunity for a team to dramatically increase revenues earned from local broadcasting, but it also provides the team owner with a valuable asset against which capital can be raised. Therefore, a team’s national and local television contracts are important factors in determining the team’s value. Global media contracts are a possibility for some of the biggest European soccer clubs, which provide them with a revenue stream that is unavailable to their North American counterparts due to the more restrictive league rules regarding global broadcasting found domestically.

The league in which a franchise plays impacts its value in several ways. As previously mentioned, the league’s national broadcasting contract guarantees revenue to the franchise. Second, the league’s revenue sharing agreement can either enhance or hinder the value of its franchises. A league with a high degree of revenue sharing can ensure the long-term viability of its franchises by guaranteeing them monies every year and protecting them against a shortfall in nonshared revenues in any particular year. However, this may harm the short-term value of franchises that generate significant amounts of revenue by redistributing their wealth to other franchises. The lack of a meaningful revenue sharing plan in European soccer leagues can either help or hinder the value of a club depending on its ability to generate revenues on its own.

A league’s collective bargaining agreement with its athletes can affect the value of its franchises. A settled labor situation with a mechanism for control over player compensation benefits owners by providing them with an assurance that their revenue-generating games will continue to be played. A mechanism for controlling player compensation is vital in that, similar to most businesses, a sports franchise’s ability to predict and control its costs is a very important aspect of its operations. The single greatest cost to professional sports franchises is player salaries; a salary cap provides a team with a degree of cost certainty by dictating the amount of money that it can spend on athlete compensation. Although loopholes and exceptions to these salary-containment systems have somewhat eroded their benefits, they still enhance team values. It follows then that the legal prohibition of cost containment mechanisms in European soccer leagues inhibits the value of most of the clubs.

The debt accumulated by a team also requires consideration. Team debt typically arises when an owner purchases a team and when the team must pay for part, or all, of the construction costs of a new facility; this obligation may be onerous and can ultimately cause the transfer of a team for a lower cost. It is for this reason that it is often better for a sports franchise to lease rather than own its playing facility, especially if the lease terms are advantageous. A team’s debt is often guaranteed by a revenue stream accruing from its facility. This negatively affects a team’s cash flow because the revenues that would otherwise be used for team operations must be utilized to service the debt. In an attempt to protect its members, each league has enacted rules that limit the amount of debt that can be accumulated by a team. However, these debt limitation rules have numerous exceptions and are rarely enforced. Again, the contrast with European soccer leagues is striking. A number of European clubs have amassed stifling amounts of debt due to the run up of franchise acquisition costs, facility-related costs, and player acquisition and salary costs.

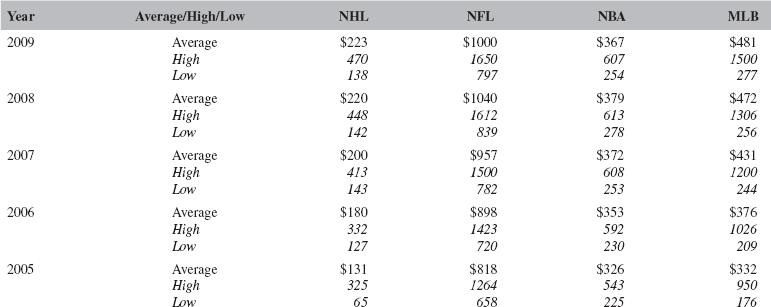

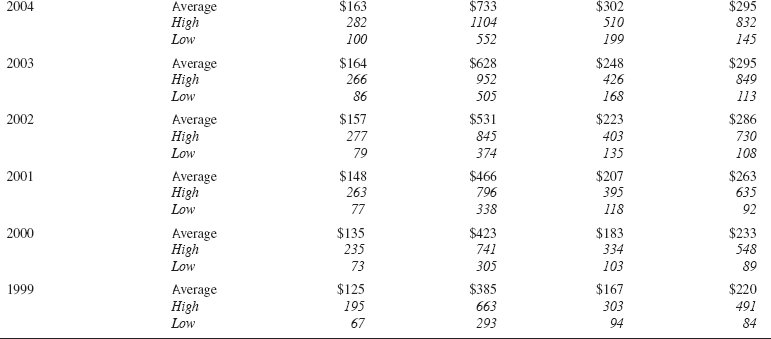

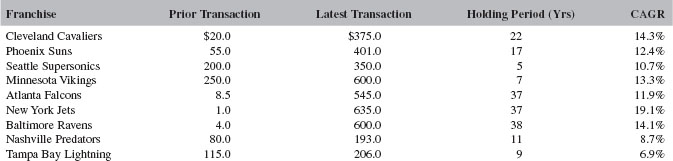

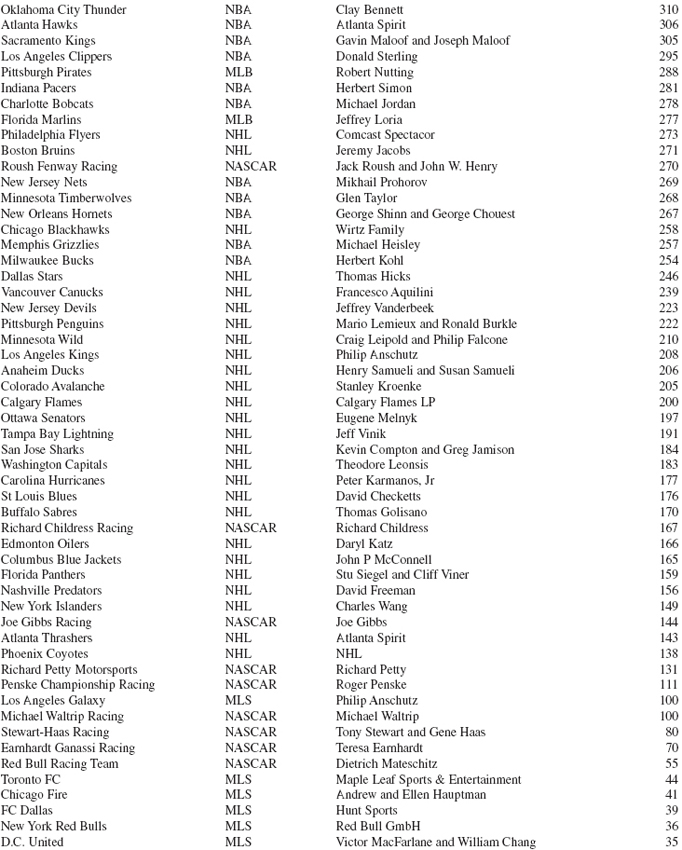

Table 1 Forbes Franchise Values as of January 2010

Source: Forbes.

The tax benefits associated with ownership of professional sports franchises have an impact on value, as well. (See Chapter 1 for further discussion of this topic.)

The real estate value of the sports franchise must also be considered. A real estate developer may purchase a sports franchise as part of a larger development scheme upon which profits can be realized, even if the team itself may suffer operating losses. This will increase the transfer price of the franchise. The nature of the seller will affect team value as well. A corporate owner typically must sell the franchise fairly quickly in order to appease analysts or shareholders, whereas an individual owner, realizing the significant consumption value associated with team ownership, must be compensated for the loss of the psychological premium that team ownership brings. Consequently, an individual owner is less likely to sell the team with any degree of urgency and can thus afford to “hold out” until obtaining the desired price. Thus, the purchase price of a team sold by a corporation may be lower than a comparable franchise sold by an individual.

The quality or reputation of a team as measured in terms of its win–loss record also may impact value, as may the value of its brand. Although seemingly irrational due to the cyclical nature of sports, a team’s recent performance record may factor into the valuation equation. A team’s brand may come into play and enhance the franchise’s value if the team is one of the handful of “trophy” teams in both the North American and European soccer leagues that resonate well beyond their home market.

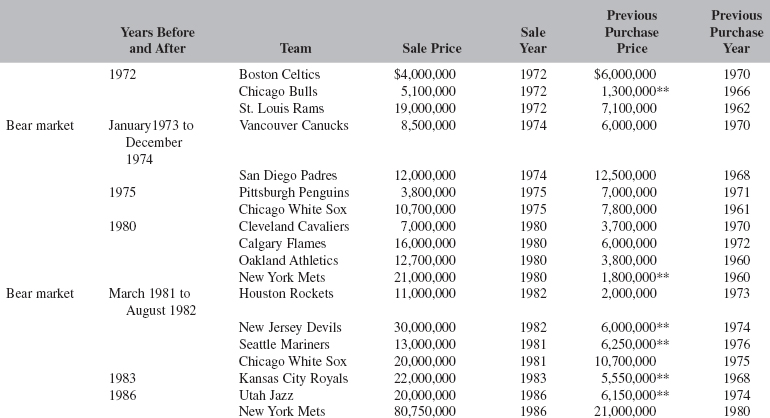

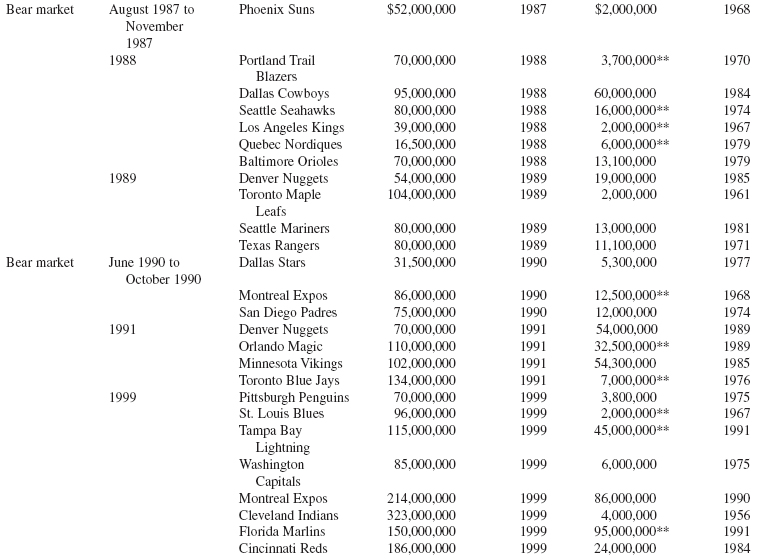

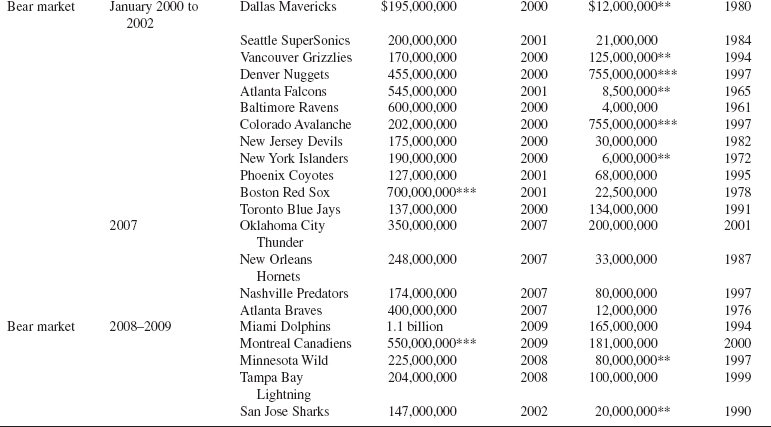

*Except for sales occurring in 2001, represents the percent change from last close in January in the year of the prior sale to the last close in December of the sale year.

**Expansion fee

***Sale includes other assets

Sources: Moag and Company Research; Pay Dirt; additional data on file from authors.

The market size of the city in which a team is located may be important because of its potential effect on the size of the team’s fan base, the local television contract, local sponsorship and advertising agreements, and the number of large corporations and wealthy individuals in the city with the ability to afford luxury seating. In addition, the degree to which the market is saturated by the presence of other professional sports franchises may impact a team’s value.

It is for all of these reasons that valuation of professional sports franchises is considered more of an art than a science. The selections used in this chapter shed additional light on the valuation process. In the first article, Ziets and Haber of sports advisory firm MZ Sports establish the background for the discussion that ensues in the remainder of the chapter. The chapter continues with a Fitch Ratings research publication that provides an overview of the rating process for sports-related transactions. In the third and fourth excerpts, Humphreys and Mondello and then Alexander and Kern offer in-depth scholarly analyses of the determinants of the valuation of a sports franchise. Phillips and Krasner take a peek into the future of sports franchise values in the final selection.

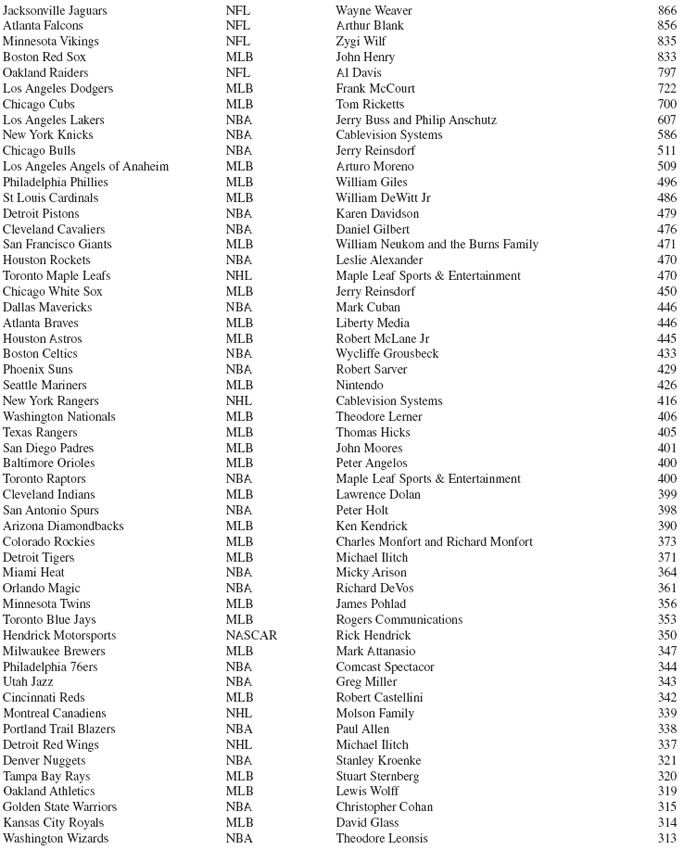

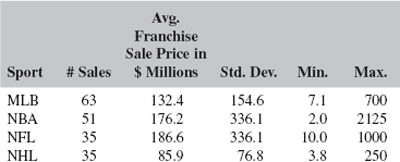

See Table 1 for a list of Forbes franchise valuations; Table 2 for a list of franchise sales before, during, and after bear markets; and Table 3 for a list of average league franchise valuations.

OVERVIEW

THE FINANCIAL VALUATION OF SPORTS FRANCHISES

Mitchell Ziets and David Haber

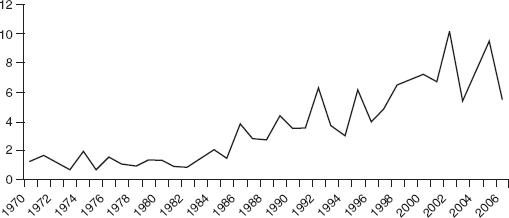

Figure 1 Franchise Valuations

Source: Rodney Fort, “Rodney Fort’s Sports Economics,” Sports Business Data page, 2005, http://www.rodneyfort.com/SportsData/BizFrame.htm, accessed January 2007. Reproduced with permission of ABC-CLIO, LLC.

Figure 2 Average Percent of Revenues Spent on Player Salaries by League

Source: MZ Sports LLC proprietary research. Reproduced with permission of ABC-CLIO, LLC.

Figure 3 CBA Term for Each League

Source: MZ Sports LLC proprietary research. Reproduced with permission of ABC-CLIO, LLC.

Figure 4 Per-Team National Media Revenues by League

Source: Street & Smith’s Sports Business Journal Research, “Sports Rights Fees,” Street and Smith’s Sports Business Daily, 2006, http://www.sportsbusinessdaily.com/index.cfm?fuseaction=tdi.main&departmentId=24#sportsrightsfees, accessed January 2007. Reproduced with permission of ABC-CLIO, LLC.

Figure 5 Average Nielsen Ratings

(1999–2007) by League

Source: Street & Smith’s Sports Business Journal Research, “Final Nielsen TV Ratings,” Street and Smith’s Sports Business Daily, 2006, http://www.sportsbusinessdaily.com/index.cfm?fuseaction=tdi.main&departmentId=24#finaltvratings, accessed January 2007. Reproduced with permission of ABC-CLIO, LLC.

Figure 6 Franchise Sale Prices vs. Market Size

Sources: MZ Sports LLC proprietary research; and AR&D Television Branding, “Nielsen Media Research Local Universe Estimates,” AR&D Television Branding website, www.ar-d.com/pdf/DMAListing_2005-2006.pdf, accessed January 2007. Reproduced with permission of ABC-CLIO, LLC.

Note: (1) Franchise was sold during the term of the 1994–2004 Collective Bargaining Agreement

(2) Franchise was sold during the term of the Collective Bargaining Agreement signed in 2008

Figure 7 Franchise-Owned Regional Sports Networks

Source: AR&D Television Branding, “Nielsen Media Research Local Universe Estimates.” Reproduced with permission of ABC-CLIO, LLC.

Figure 8 Historical Revenue Multiples

Source: MZ Sports LLC proprietary research. Reproduced with permission of ABC-CLIO, LLC.

CREDIT RATINGS

FITCH RATINGS—CRITERIA REPORT GLOBAL SPORTS RATING GUIDELINES, MAY 9, 2007

Chad Lewis, Jessica Soltz Rudd, Laurence Monnier, and Cherian George

SUMMARY

The continued evolution of professional sports from entertainment to big business has spurred billions of dollars of capital-market transactions in the past two decades at the league, franchise and facility level. Fitch’s core credit view of the underlying factors associated with sports-related transactions has not changed. Primary factors that Fitch analyzes to determine all sports ratings include the following:

• League economic model.

• National television contracts.

• Player salary structure.

• Revenue sharing among member clubs.

• Role of league in team financial matters.

• League debt limits and other financial policies on franchises.

• Relationship between league and players’ union.

• Locally generated revenues.

This report lays out Fitch’s view in more detail and guides readers through the analytical framework used in assessing the credit quality of a professional sports league, a professional sports franchise and various types of sports facilities based on the underlying financial viability and fundamentals, economic factors and legal analysis. The underlying economics of a professional sports league play the most critical role in assigning sports ratings. Professional sports’ economic models (consisting of players’ salary structures, media contracts and revenue-sharing policies, among other factors) have become more evident and highlight the leagues’ structural credit differences.

Fitch’s universe of sports ratings includes leaguewide credit facility ratings, franchise ratings, and stadium and arena ratings. Specifically, within the franchise ratings, Fitch has analyzed both corporate and asset-backed transactions. Fitch’s stadium and arena ratings universe includes transactions involving the four major U.S. sports leagues—the National Football League (NFL), Major League Baseball (MLB), the National Basketball Association (NBA) and the National Hockey League (NHL)—as well as European soccer leagues. The primary security structures in the stadium and arena ratings universe include a pledge of all facility-generated revenue, a pledge of selected facility-generated revenues, a pledge of various tax-generated revenues and asset-backed structures.

Fitch views sports ratings from a top-down perspective for team-related ratings, as well as project finance stadium and arena financings. From this perspective, team and sports facility ratings are analyzed within the operating and regulatory environment of their parent league, which provides analysis of that league’s economic model, financial policies and legal structure. Consequently, determining these ratings is in some ways analogous to the “sovereign ceiling” concept of the international bond markets when rating the debt instruments of nations and their subsovereigns or applicable corporate entities, such as provinces, states or corporates that are part of and operate within that respective nation’s laws and financial regulations. For example, Fitch maintains an ‘A+’ rating for the NFL’s senior unsecured notes, and it is unlikely that an individual franchise in the NFL would be rated on par or above the league. For sports facilities, the rating ceiling could be somewhat different, though this is generally unlikely, as stadiums and arenas may have strong economic characteristics stemming from multiple anchor tenants and the ability to host many other revenue-producing events.

The first two sections of this report specifically detail Fitch’s underlying analytical approach and the credit factors incorporated in rating the four U.S. professional sports and the franchises within those leagues. An appendix has been provided that specifically discusses credit fundamentals associated with European soccer transactions. Many of the facility-based credit factors are amendable to European soccer transactions, provided a thorough understanding of the league and franchise exist.

Construction and environmental risk factors and analyses are largely similar and applicable across countries. The legal framework in which a facility is developed is also generally similar across countries, with the stipulation that more or less stringent applicable laws may have a positive or negative rating effect, depending on legal impediments specific to an area that are more favorable or detrimental to a transaction.

PROFESSIONAL SPORTS LEAGUES

A professional sports league analysis is the backbone for all sports-related transactions. The fundamental makeup and economic model of a league is the most significant rating factor in assessing the credit quality for the league, as well as franchise and facility transactions. The primary source of revenues, national television contracts, provides a strong, stable revenue source. Additional shared revenues, such as pooled suite, club seat and ticket revenues, are viewed favorably as they provide revenue diversity. The framework set in place for the largest expense item, player salaries, is the second most important factor in assessing league credit. In addition to the financial and economic profile of a league and potential changes to the general economic framework, Fitch carefully monitors fan attendance levels, television ratings, average ticket prices, changes and trends in ownership, player and union relations and other factors that may have a material effect on the quality of the sports product.

A league structure incorporating strong national television contracts, appropriate salary structure, a strong diverse corporate sponsorship and advertising base, established strong debt policy, league-level support to assist distressed franchises, a solid history of limited work stoppages, and strong covenants and legal provisions is viewed most favorably by Fitch and would be a strong candidate for an investment-grade rating. Leagues that incorporate some of the key rating factors may also achieve investment-grade ratings.

League Revenues

Fitch views positively league policies that share national television revenues equally, as compared with a league that distributes national television revenues based on a team’s performance. From a ratings perspective, equal distribution provides, to some extent, additional parity among franchises by providing some level of revenue certainty per franchise, resulting in a more level playing field for franchises. While locally generated revenues may be dramatically different between small and large market teams, significant revenue sharing from a league level helps to mitigate significant disparities among franchises. Leagues that equally distribute revenues, rather than distribution based on a franchise’s on-field performance and winning record, provide greater revenue certainty and less potential for revenue disparity among franchises. The concept of distribution of revenues based on performance-based measures may be exacerbated if a franchise is unable to generate significant local revenues from ticket sales and other stadium-derived revenues. From Fitch’s standpoint, a league structure that bolsters financial parity among franchises has the potential to drive competition between franchises and grow and maintain spectator interest.

Salary Structure

The various salary structures across existing professional leagues around the world can have a substantial effect on the credit ratings of those leagues. Salary structures ranging from a “hard salary” cap to a “soft salary” cap to no salary cap exist in professional sports today. A hard salary cap establishes a maximum for player payroll. The player payroll may be adjusted upward or downward based on the index to which it is linked. For example, a hard salary cap may be linked to a percentage of the national television broadcast rights fees or a percentage of total league-generated revenues, including national television broadcast rights fees, shared suite and club seat and other nationally shared advertising and sponsorship agreements. Essentially, the player payroll and a team’s share of the national media contracts and other revenue agreements are adjusted in tandem. This is viewed as a credit strength because a franchise’s largest expense item, player salaries, are not able to exceed a certain percentage of defined revenues; thus, it is highly unlikely that expense growth would largely increase at a rate greatly exceeding total revenue growth. Additionally, given that franchises spend the same amount of money on player salaries, teams should have a similar talent level, which drives competition. In Fitch’s opinion, competition between franchises is a key underlying factor for the ability of a league to sustain strong spectator interest over the long term.

A soft salary cap may generally have the same structure as a hard salary, with exceptions for veteran or key franchise players. Exceeding the soft salary cap requires a franchise to pay a fixed amount of money, often equal to the amount above the threshold, into a league’s central fund for equal distribution to the other franchises in the league. The absence of a salary cap (i.e., an owner may choose to spend as much or as little on a franchise payroll) is viewed as a weakness to a league, because there is less expense certainty. Additionally, a significant disparity between franchise payrolls and the subsequent higher talent levels lured by larger payrolls has the ability to risk the long-term competitive nature of the league.

Fitch views the combination of equal distribution of revenues, coupled with a hard salary cap, as a strong foundation for a professional sports league. The current U.S. (NFL) economic model is an example of this. The NFL has a hard salary cap and adjusts player payroll according to the annual amount of national broadcast rights fees and other shared pooled revenues, which are distributed among all the franchises equally.

League Debt Policies

An established debt policy at the league level for franchise-level debt is viewed positively by Fitch. A debt policy that caps a franchise’s maximum debt to an established fixed asset value based on recent historical franchise sales is viewed more favorably than a debt policy that links maximum debt levels to a financial indicator, such as EBITDA. While an EBITDA debt test provides a solid financial indicator, Fitch generally views possible short- to medium-term fluctuations in EBITDA as more volatile than possible declines in franchise values. A franchise may decide to sign a “high profile” player in a year and cause financial margins to decline for that year or the next. Conversely, Fitch’s proactive monitoring of franchise sales across the leagues for the past 10 years supports this premise of greater stability in franchise values. Fitch would expect that, and views favorably, a debt policy linked to the franchise value would yield no more than a debt-to-franchise value of 25% and a debt policy linked to EBITDA would link maximum debt to no less than 10 times (×) EBITDA, which Fitch notes as being on the high end of the spectrum for EBITDA tests.

League Work Stoppage History

The relationship between the players’ associations and league and history of work stoppages is a key factor in rating leagues. Fitch assesses the historical labor environment and any material changes that have occurred to the current environment. A strong history with limited disputes from both sides is viewed positively. Historical disputes over key elements of labor agreements that have been changed and agreed upon, as well as an overall current peaceful labor environment, are viewed favorably.

SPORTS FRANCHISES

An understanding of league policy and procedures, as well as its underlying economic model, is a prerequisite for considering franchise fundamentals. It is the competitive nature and long-term stability of these associations that foster and preserve fan interest, which, in turn, attracts advertisers and broadcasters. Macro- and microinfluences, such as demographics, stadium and arena issues, as well as management ultimately differentiate the financial profiles at the team level. These influences help serve as key credit support measurements.

Fitch also notes, with the advent of various leaguewide borrowing programs in the United States, the majority of franchises seeking capital markets debt have elected to borrow from leaguewide programs as opposed to entering the capital markets. Arguably, the leaguewide programs in the United States give franchises a lower cost of borrowing, because the debt is secured by league revenues and debt service is paid prior to franchises receiving the revenues, which Fitch views more favorably.

Although general rules can be applied, rating debt at the franchise level remains a case-by-case analysis. In reviewing an individual team transaction, several key questions need to be asked, including the following:

• Can a team support both its operating cost and its debt obligations?

• Are there appropriate credit-protection measures in place to support debt service and asset valuations in a downside scenario?

• Does the league take an active role in ensuring the financial viability of its member teams, as well as the financial claims of creditors?

• What has been the track record of ownership in generating consistent financial results?

• Has the team forged a special relationship within a community that makes it an invaluable asset and source of pride?

A thorough understanding of the answers to these questions serves as the basis for Fitch’s sports ratings at the team level.

Because most debt at the team level is secured by a direct lien on the franchise, team debt can be considered a hybrid transaction, incorporating elements of both a traditional cash flow obligation, as well as elements of an asset-based transaction. As a result, Fitch’s approach gives appropriate consideration to both of these measures in establishing a senior secured rating. A more favorable rating will be considered where the team is the legal obligor (team-level debt), as opposed to holding company or partnership (holdco. or partnership) debt. The position of the borrower addresses such issues as structural subordination. Debt at the holdco. level is structurally subordinate to debt at the team level, similar to the concept of a holdco. in traditional corporate finance.

Establishing a senior secured rating is a two-step process. The first step involves establishing a timeliness of repayment rating or implied senior unsecured rating. The second step involves notching from the implied senior unsecured rating based on the collateral coverage provided by the value of the franchise.

IMPLIED SENIOR UNSECURED RATING IN SENIOR SECURED RATINGS

The implied senior unsecured rating effectively serves as the starting point for the secured rating. Key considerations for establishing an implied senior unsecured rating consider the overall quality of the team’s key revenue components. More specifically, Fitch differentiates contractual revenue streams from noncontractual revenue streams. Contractually obligated revenues (COR) primarily include national and local media contracts, local sponsorship agreements and luxury suite rentals. Sometimes revenues are referred to as “highly probable.” These revenues are not explicitly contractual but have a contractual component that may be represented as highly probable. Highly probable revenues are analyzed and reviewed to determine the likelihood that they will be realized. Fitch will only consider such sources if historical evidence suggests a high probability of realization. Season ticket sales, which have demonstrated consistent renewals over a long period of time, may be considered highly probable. The greater portion of revenues deemed contractual and/or highly probable, the higher the “quality” assigned to these revenue streams.

Another key analytical factor is a team’s COR as a percentage of player payroll. Because player payroll constitutes the largest cost component for a team, the extent to which player cost can be matched against contractual revenue streams helps to assess a team’s reliance on less certain revenue streams to support player payroll, operating expenses and debt service. COR representing more than 70% of total player expenditures will, on average, result in a higher implied senior unsecured rating. Conversely, teams with COR substantially less than 70% of player cost will likely receive lower implied senior unsecured ratings. Teams operating in leagues with weak restraints on player costs and loose debt limitations, as well as those in which the COR is less than 70%, would most likely have the lowest implied senior unsecured rating.

EBITDA may not be the most accurate proxy for a team’s cash flow, given that GAAP EBITDA does not take into account items such as cash bonuses, deferred compensation and other cash items that are not reflected in the income statement. Therefore, traditional cash flow based credit metrics, such as total debt/EBITDA and EBITDA/interest expense, have limitations when valuating team-level debt obligations. With this in mind, Fitch uses slightly altered credit measures in rating team debt.

Leverage

The ratio of debt (at the team level) to a team’s annual COR should not exceed 2.0x for investment-grade consideration.

Debt-Service Coverage

Depending on the league, as a general guideline, the Fitch base case and Fitch stress case have targeted minimum ratios of operating income (total revenues less total operating expenses and cash bonuses) to annual debt service to range between 2.25x and 1.75x and 1.75x and 1.40x, respectively, for investment-grade consideration.

As mentioned previously, the relative strength of a league’s economic model is also considered in establishing an implied senior unsecured rating. For example, the NFL’s economic model is extremely strong and helps to create a favorable credit environment for the league’s individual franchises. This is in part due to the NFL’s robust television contracts that roughly match a team’s largest expenditure: player payroll. For leagues in which revenues are not as equitably distributed, the effect is illustrated via a performance gap. Small-market franchises find it increasingly more difficult to compete with large-market teams, as they do not have comparable economic resources to procure top player talent. From a ratings perspective, a lower shared percentage requires greater scrutiny on a franchise’s local revenues. These include gate receipts, local broadcasting rights and stadium-related revenue. These revenues are more closely tied to market demographics and team performance.

Collateral Coverage in Senior Secured Ratings

The second step in rating franchise debt assesses the overall collateral coverage provided by a pledge of the franchise. Recent transaction prices serve as the most relevant valuation measure. From an asset coverage standpoint, most teams exhibit significant asset coverage over committed secured debt amounts. Additionally, leagues with actively enforced debt policies that limit an owner’s ability to leverage a team help to ensure sufficient overcollateralization. Fitch will notch above the implied senior unsecured rating by as many as three notches where ultimate recovery of principal is certain. In general, to receive a three-notch enhancement, loan to value (LTV) should be 50% or less. The 50% LTV guideline is a general rule and should be matched against the overall credit quality of the team.

ANATOMY OF A SPORTS FRANCHISE TRANSACTION

The primary credit risks in a sports franchise transaction involve renewal of the national media contracts (as well as local media contracts and other COR, where appropriate), the possibility of a work stoppage and a deterioration in franchise values. Fitch views favorably debt obligations that contain structural features that help to offset these risks.

National Media Contracts

Fitch considers renewal risk of national media contracts to be among the most important factors in assessing the credit-worthiness of sports franchises. Because broadcasting rights fees provide a substantial portion of a team’s revenues, any adverse change in these contracts would likely have a material effect on a team’s overall credit profile. Ideally, the tenor of the debt obligation should expire prior to the expiration of the national media contracts so as to avoid renewal risk. When the maturity of the rated debt obligation goes beyond the expiration of the national media contracts, Fitch considers the historical trends in renewals for sports programming and for the respective league. In cases where creditors are exposed to broadcast contract renewal risks, covenants that set minimum thresholds for national broadcasting renewals are helpful in providing remedies in the event leaguewide broadcasting contracts are lower than anticipated. Possible remedies may include mandatory ownership capital calls and cash lockups prior to the renewal of national broadcast contracts. Fitch views positively structural features, including covenants, that allow creditors to readjust credit risk in light of lower than anticipated league wide broadcasting renewals.

Labor Environment

Fitch views positively structural provisions that address potential work stoppages. This applies to instances where the collective bargaining agreement (CBA) expires prior to the maturity of the rated debt obligation. While the contractual terms of the national media contracts may provide for the continued receipt of broadcasting fees during a work stoppage, teams will not receive any game-related income (ticket sales) and may have to remit refunds to ticketholders and sponsors. A labor contingency reserve helps to offset this risk by protecting debt service in the event of a work stoppage. Typically, labor contingency reserves will fund one year of debt service. Similar structural protections are required for investment-grade sports facility ratings.

Collateral Coverage

Similar to an asset-based transaction, collateral valuations are a key measure of credit support. Fitch views favorably covenant triggers that set minimum team valuations. Periodic appraisals and/or recent purchase transactions may serve as the mechanisms for collateral monitoring. Fitch examines the rights of creditors to readjust credit risk if asset valuations decline. A mandatory debt repayment to reduce LTVs and asset coverage to prevailing rates is viewed most favorably as an offset to potentially declining franchise values.

Support Agreements/Guarantees

In some cases, a team’s underlying credit profile may be extremely weak and rated low on a stand-alone basis. In these instances, a credit may require some type of third-party support. This support usually takes the form of an operating support arrangement in which the owner or supporting entity agrees to fund operating losses unconditionally or up to a specified, agreed-upon amount. Fitch’s implied senior unsecured rating starts with the team’s creditworthiness on a stand-alone basis and is adjusted to reflect the level of support provided by the outside party. In considering the level of support, a review of the outside party’s financial ability to cover operating losses and debt repayment is considered. The financial strength of the support provider, as well as the level of support required by creditors, helps determine the level of enhancement given to the implied senior unsecured rating.

Lockbox Mechanisms/Accounts

Certain lockbox or debt-service account (DSA) structures may be established to provide debt service through contractual revenue streams. Franchise debt transactions may attempt to somewhat mitigate team financial risk by creating a lockbox structure that directs national broadcasting rights fees into a lockbox account. The lockbox account deducts amounts required for debt service and remits the remaining portion to the team. Furthermore, the transaction may require additional funds be held in the DSA as added debt-service protection. The DSA and lockbox arrangement somewhat insulate creditors from team-related risk. It should be noted that these structures only serve as a method of payment and do not necessarily protect creditors’ claims should the team file for bankruptcy. The automatic-stay provision within the bankruptcy code could freeze interest and principal payments owed to creditors.

FRANCHISE VALUES

One of the biggest unknowns in sports financing is the future of team valuations, which is a key component in a sports franchise rating analysis. Rather than trying to predict the future of team valuations, it may be more useful to understand the underlying fundamentals that support franchise values. Some of these fundamentals include the relative scarcity of sports assets, the exclusive right to operate, the economics of the respective league and the prestige associated with owning a sports team.

Relative Scarcity of Sports Assets

The consensus from officials across all leagues seems to suggest that demand far exceeds supply for ownership of a professional sports team, although Fitch notes that current demand may change in the future. However, given franchise sales over the past 10 years, Fitch believes the likelihood that franchise values would decline in the near term is highly unlikely; thus, demand will remain strong. With waiting lists of buyers and a limited amount of teams available for purchase, competition for ownership can be intense and drive up the price paid for a team, in many cases. However, demand for clubs can differ significantly based on the team’s local market, history of support and the league in which it plays, among other factors.

The Exclusive Right to Operate

The right to operate a team is solely and exclusively granted by the governing league. The right granted by the respective league effectively serves as a key barrier to entry. This right to operate allows an acquiring owner exclusive access to national media revenues and other team-generated revenue streams. Moreover, each major sports league has explicit rules prohibiting competing ownership within the same market. This effectively provides an owner with the ability to operate in noncompetitive geographical markets (for the respective sport).

The Economics of the League

As discussed in the league analysis section, the underlying economics of a league help determine the overall attractiveness of a franchise. One of the major differentiating factors between sports leagues is the allocation of revenues among member teams. For example, the NFL equitably distributes a high percentage of total leaguewide revenues and places a hard cap on players’ salaries. This policy puts franchises on generally level fiscal terms, translating into greater on-field competition and fan interest. As a result of these policies, the overall attractiveness, from a financial standpoint, of NFL member teams is increased.

Trophy Assets

The prestige associated with owning a professional sports team is an intangible benefit that is not easily measured. Instant visibility is gained upon owning a sports team, as fans and local media perceive the owner as a key community figure. Like a valuable piece of art, some of the benefits of owning a professional sports team are less scientific. The emotional aspects of ownership may play a big role in the overall purchase decision.

To the extent that debt is used to finance a significant portion of a purchase price, prudent credit decisions must still be made. Depending on the operating history of the respective franchise and prevailing macroeconomic trends in the industry, credit-protection measures, such as material debt amortization and/or mandatory debt reductions, may help offset credit concerns relating to future franchise values and refinancing risks.

Cash Flow Analysis

In addition to the aforementioned factors analyzed in determining franchise values, the ability and amount of positive cash flow a franchise generates is also analyzed. It is important to note that a thorough understanding of the league framework in which a franchise operates in is a pivotal factor when analyzing cash flows of a franchise in the value of a franchise. A franchise that plays in a league where there is substantial leaguewide revenue sharing and a salary cap has a stronger foundation to produce positive cash flow, because a significant amount of overall revenues flow from national television contracts and the largest expense item, player salaries, is fixed. While franchise performance may affect other revenues, a franchise in a league that does not have significant revenue sharing from a national broadcast agreement and a salary cap may be more susceptible to revenue fluctuations based on on-field performance, which would ultimately have a greater effect on cash flow. Management’s ability to grow revenues in addition to leaguewide revenues from local media contracts, average ticket prices, advertising and sponsorships, and concessions and novelties is an important rating factor.

Management’s historical track record and ability to manage and adjust expenses in a period of declining revenues is also a key credit consideration. Fitch recognizes that while other team-level expenses, such as player development, general administrative costs and benefits are a small portion of total expenses, they are important to a franchise. Historical demonstration and understanding management’s ability, plan and implementation to manage expenses is crucial. Fitch will carefully monitor any changes in league revenues and locally generated franchise revenues and any potential short-term and long-term effects on cash flows.

SPORTS FACILITIES

The increasing importance of sports facility generated revenue to teams’ financial health spurred a significant surge of new construction, as the changing model of professional sports has proven that new facilities are vital to a franchise’s financial success. New facilities have the ability to generate new revenue streams, such as naming rights, club seats and suite revenues and, generally, strong corporate advertising and sponsorship revenues. Older stadiums that have not benefited from the aforementioned new revenue streams and, in many cases, lease agreements that limited financial growth often impede the financial potential of a franchise.

Historically, most stadiums and arenas were financed under the same city-building infrastructure theory as municipal properties; that is, the buildings were intended to be used by all and constructed solely with public dollars for the benefit of the town and people. However, as professional sports leagues expanded into big business, the pressure for modern stadiums with new and increased revenue drivers pushed the trend of facility construction into a new era, much of which with private dollars. Several methods of financing construction have been used, including public financing via tax-generated sources, stand alone nonrecourse project financing and asset-backed securitization of stadium revenues. It is important to note that almost every sports facility financing package is different and has consisted of elements of either tax-backed or project financing, or both, as well as private loans or private cash. However, certain underlying factors are similar and necessary in all sports facility transactions, such as the franchise’s lease agreement with a nonrelocation agreement or a “promise to play” for the term of the debt.

From a project finance perspective, public dollars are considered pseudo equity, helping to bolster the economics of the project finance bond transaction. Fitch observes that there is not a consistent debt-equity structure utilized, as there are many different ways to finance a large-scale project, and that each transaction is structurally different. From a bondholder’s perspective, the lower the leverage and the higher the debt-service coverage the better, but both factors are different in every transaction. While there is almost always a mixture of public debt, private debt and private equity contributed to sports facilities, Fitch notes that, in many cases, the public sector retains the title and ownership to the stadium or arena.

Projected cash flows, debt-service coverage and liquidity levels for these types of project financing transactions must undergo various base and stress test case scenarios. Pro forma projections must be able to withstand several sensitivity analyses. Generally, assumptions in the stress test include reductions in base attendance levels, decreased percentages of premium seating renewals, the exclusion of certain revenue from other events and a significant reduction of other revenue, such as naming rights, concessions, advertising and parking. Structural protections, such as debt-service reserve funds, must also be included in the transaction to mitigate the risk of a work stoppage. The appendix attached to this report, and further discussed below, provides an indication of various assumptions Fitch will build into a base-case and stress-case scenario.

Furthermore, Fitch assesses the viability of each sports project finance transaction through a detailed analysis of the facility’s service and market area, franchise and venue competition, project construction risk, the respective league of the tenant franchise, the quality of the franchise and the strength of facility management and operations.

PROJECT FINANCE—FINANCIAL PROFILE

In general, for project finance sports facility ratings, it is important to note that Fitch uses fan attendance averages from historical trends, rather than from pro forma attendance estimates. Additionally, the rating is based largely on COR, which is not directly dependent on the on-field success of the home team but rather on presigned long-term leases the sports facility enters into with the various counterparties, such as naming rights partners, advertising partners, long-term suites and club seat agreements, guaranteed concession agreements and team rent payments.

Although revenues in entertainment-dependent facilities are often considered volatile because of their nonessential nature, a high percentage of COR provides a degree of stability and predictability to the revenue stream. Key elements of COR include solid lease agreements with the anchor tenants, premium seat license agreements, long-term contracts with concessionaires and advertisers and, possibly, some type of guaranteed public support (such as a sales tax rebate). It is important, for investment-grade consideration, that transactions have at least 60% of projected pledged revenues contractually obligated.

Luxury Suites and Club Seats

Premium seating has become a major source of security for project finance transactions. Premium seating generally consists of luxury suites and club seats that range in price from $50,000–$350,000 and $500–$5,000 per annum, respectively. The pricing structure is driven by demand, actual suite location and associated amenities, the strength of the tenant franchises and the number of included events. Due to their high cost, suites are normally leased by corporations, and Fitch analyzes the service area’s corporate base compared with the overall supply of suites in the area. The length of premium seat leases varies, with average terms ranging between three and 10 years. From a debtholder’s perspective, a transaction with staggered lease expiration dates mitigates the risk of a significant percentage of leases expiring in any given year, which poses renewal risk. Demand factors for luxury seats are based on economic conditions in the local area, historical franchise performance and fan support. For luxury suite agreements, Fitch generally assumes the payment schedule according to the initial terms of the agreement and stresses the renewal of those agreements. Club seat revenue can also represent a significant amount of pledged revenue. Club seat holders are typically small businesses and wealthy individuals, and Fitch believes club seat demand is more dependent on the franchise record than luxury suites.

Naming Rights and Sponsorship Agreements

Naming rights agreements are another revenue source that can be part of a basket of revenue streams that can secure project bonds. Naming rights enable a corporation to name the facility after itself or one of its products. Naming rights agreements may include a substantial upfront payment, in addition to annual payments, typically well in excess of $1 million. A naming rights counterparty analysis is important to the rating of the project debt, and the underlying rating of the corporation is considered. Projected income may be discounted for low-rated counterparties. Additional corporate-related income may be derived through sponsorship and advertising agreements.

Personal Seat Licenses

Personal seat licenses (PSLs) are another source of revenue earned by facilities. A PSL is purchased by individuals, giving them the right to buy season tickets for a certain period of time or for the life of the facility. PSL revenue is typically collected in the initial stages of the construction process, so it is often used as equity to partially fund facility construction, as opposed to being utilized to retire debt.

Season Ticket Sales and Concessions Revenue

Season tickets, and to a greater extent gate receipts, comprise relatively volatile revenue streams in certain sports and markets, since the demand is highly correlated to the franchise’s current performance and economic conditions. Stress levels for these revenue streams are significant and depend on market location, the inclusion of an upfront payment or PSL, franchise support and demonstrated continued demand, such as historical revenues and the existence of a ticketholder waiting list. The guaranteed revenue under a concession agreement is based on calculations that incorporate fan attendance levels and varying percentages of gross annual receipts net of sales taxes. To determine the likelihood of payment of the guaranteed portion of the concession revenue stream, Fitch analyzes the historical concession revenue performance. The strength of the guaranteed revenue stream is also based on the counterparty’s credit rating and its position in the industry. The agreement may include a substantial upfront fee to the facility and a guaranteed portion that is significantly lower than the historical concession revenue generated. Inclusion of these provisions partially mitigates the risk that an obligor may default on its obligation and increases the ability to attract a replacement concessionaire in the event of unacceptable performance.

PUBLIC FINANCING

Traditionally, there has been substantial public support in sports financing, as state governments, local governments and special tax districts pledge support to the projects in various ways. Tax-supported sports transactions have been structured as general obligation bonds, lease-backed bonds and dedicated tax bonds, among others. Specific taxes earmarked to support facilities, including taxes on tobacco and alcohol, general sales taxes, accommodations taxes for hotels and motels, and ticket surcharges, among others, have been used to secure the debt issued for sports facilities. The use of accommodations taxes is a popular method of financing the debt, because it is perceived that the project will attract visitors who, in turn, will occupy the hotels and motels. This method of financing, along with similar tourist development taxes, such as those on rental cars, are politically more palatable and, consequently, may be more successful in gaining local support, because they primarily affect visitors, as opposed to local residents.

LEGAL STRUCTURE

Various legal agreements establish a project framework and each party’s obligations. Fitch analyzes project documents and their legal implications to ensure full and timely principal and interest payments and to evaluate bondholder security. Although there are several primary legal considerations inherent in all sports facility financings, all legal analyses focus on the bondholders’ legal right to receive project revenues on time and in full. Fitch first focuses on collateral pledged to the bondholders. In all sports facility financing structures, a team nonrelocation covenant is required. These agreements protect the economic value of the project by legally requiring the teams to play their games at the facility, thereby mitigating the risk that there will be insufficient revenues due to a team’s departure.

Project Finance and Securitization

In traditional project finance and those structures incorporating elements of securitization, security is derived from pledged revenues and, in some cases, a mortgage on the building, as well as a ground lease. The pledged revenues usually include several revenue streams, the right to future revenues, the right to enter into future contracts and the right to renew contracts. Fitch then evaluates the potential bankruptcy of all parties to the transaction, with a particular focus on the issuer and/or its parent, analyzing the possible delay and the potential of total disruption in bondholder payments.

Bankruptcy analysis is paramount to these transactions. The legal structure and/or supporting credit solutions are evaluated when analyzing the potential bankruptcy of all parties where their bankruptcy could affect full and timely payment to the noteholders. The primary focus is usually on the issuer, parent(s) and affiliates. Fitch’s bankruptcy analysis evaluates the ability of the entity to make timely payments to the bondholders without any interruption in the cash flows and the potential for the complete termination of those cash flows.

In project finance sports facility transactions, the debt-issuing entity is either a newly formed special-purpose vehicle (SPV) or operating subsidiary. Traditionally, the issuer has a first perfected security interest in the collateral, which is then pledged to the indenture trustee for the benefit of the bondholders. If the issuer is not an SPV, Fitch performs a financial analysis of the issuer to ensure that its bankruptcy risk is commensurate with the rating level assigned to the transaction. Transactions incorporating elements of securitization generally involve the sale of the collateral from the operating subsidiary to a bankruptcy-remote SPV created to serve as the issuer of the financing. The issuer SPV then issues bonds supported by the assets acquired by the issuer SPV. Fitch expects the counsel to the transaction would confirm that a true sale of the assets has occurred, such that the assets would not form part of the transferor’s estate if such transferor filed a petition in bankruptcy. Fitch further expects, with respect to the SPV’s issuance of the bonds, that the counsel validate that the issuer SPV has granted the indenture trustee a first-priority perfected security interest in all of the issuer SPV’s assets. Also, Fitch expects that all relevant enforceability opinions required for the transaction will be provided. Generally, both of these transaction structures include the use of a lockbox for bondholder protection.

Fitch expects that the transaction’s counsel would furnish a nonconsolidation opinion with respect to any owner holding more than 50% interest in an SPV. If an SPV has been created, Fitch evaluates the credit strength and financial viability of the SPV’s parent and affiliates. This analysis sometimes provides adequate assurance that voluntary and involuntary bankruptcy of the parent and affiliates is unlikely. In those cases in which parents and affiliates hold real estate interests or are the operator, Fitch, in addition to analyzing the parent’s and affiliates’ credit quality, assumes they become insolvent and declare bankruptcy. Since the operation of the sports facility is usually necessary to generate revenues for the parent or affiliates, Fitch, on a case-by-case basis, will analyze the business incentives for a parent or affiliate to cause consolidation. Fitch has consistently reached the conclusion that bondholders will be ultimately paid. However, a lapse in the timely payment of principal and/or interest is likely while the entity restructures. Certain reserve requirements are traditionally provided to ensure timely payment to the bondholders.

Real Estate Structures

In many tax-supported and project finance structures, as well as structures incorporating elements of securitization, the land is owned by the municipality or other parties and leased via a triple-net ground lease to the issuer through the term of the debt. Traditionally, the improvements are either transferred to the issuing entity through the sale of a fee—simple interest in the building after construction is complete or leased in the form of a triple-net lease through the term of the debt. In either instance, the interest in the building and its fixtures provide lenders with additional repayment security.

Under a triple-net lease, the lessee bears all responsibility on real estate issues, costs of operation, insurance, abatement, assignments and sublets. The leasehold and/or fee interest is sometimes pledged to the bondholders, providing additional security and often the right to replace the operator if the facility is not managed as a first-class facility or up to certain identified industry standards. However, Fitch will evaluate a structure that does not include a mortgage interest granted to the bondholders. For example, instead of a mortgage interest, the issuer and other appropriate parties may incorporate either a pledge not to encumber the fee simple while bonds are outstanding, which is offset by additional overcollateralization or a springing mortgage. Both of these structures are inherently weaker from a credit perspective but can be evaluated and included in investment-grade credits if they have appropriate offsetting strengths.

Construction Risk

As with other types of projects, construction risk often constitutes the greatest risk in the credit quality chain of a stand-alone sports facility project. In certain circumstances, it can constrain the rating to a level below what it would be after completion. Completion risk refers to the risk that the facility will not be completed on time, on budget or up to the required performance standards. For strong, economically viable projects, construction completion risk can be mitigated and investment-grade ratings can be achieved. Fitch will carefully consider the project’s complexity and technology, projected costs, delay risk and quality of contractors, as well as the terms of the construction contract.

Sports facilities vary widely in complexity, ranging from less complex open-air, single-level stadiums on undeveloped land to multilevel, retractable roof stadiums in densely populated areas and arenas in earthquake-prone areas. Fitch relies on the expertise and opinion of independent and reputable engineers (I/Es) to evaluate the design specifications of the project and the reasonableness of the development cost estimates and ongoing maintenance expenditures. The role of the I/E is crucial during the development phase, as one of the critical tasks is to monitor the works process, milestone compliance, and critical path or schedule. Typically, the I/E also approves the release of escrowed funds to compensate the contractors from proceeds of rated debt.

Construction quality and proper maintenance are fundamental for sports facilities, as they are generally considered assets with a useful life of 30–40 years that can support long-term, nonrecourse financing. The I/E’s assurances regarding construction quality and maintenance represent a vital link between the sports facility (the asset) and the financing’s structure.

Project complexity will affect the likelihood that the facility will be completed on time (delay risk). Delays can also occur due to permitting, stop-work orders, availability of critical equipment or labor, weather or seasonal conditions, and other factors. Delays that cannot be controlled by the contractor, such as force majeure and permitting, must be addressed by other means, such as compensation from insurance. Of note, potential delays and construction cost overruns caused by incomplete, ambiguous or evolving specifications, beyond the customary and often inevitable work changes requested by either the sponsors or contractor, are of great concern. Fitch expects projects financed by the capital markets will be undertaken on the basis of minimal design risk. Neither Fitch nor the I/E has the capacity to estimate the ultimate effect on project costs and cash flows from material changes in design once a project has initiated construction, especially if appropriate mechanisms, such as completion and performance guarantees from sponsors, governments or solid third parties, are insufficient or not provided.

Environmental Risk

Another major consideration is environmental risk, including remediation efforts, cost overruns, timing and insurance. Environmental issues are of greatest concern during the construction phase of a project, because unexpected expenses during this period can seriously deteriorate the credit quality of the project. Traditionally, the environmental concerns are identified, and mitigation procedures have been established prior to the project being brought to the capital markets. Also, most project finance and structures incorporating elements of securitization involve guaranteed maximum price contracts, thereby transferring responsibility for unexpected costs. Fitch will review the guaranteed maximum price contract to ensure that such risks are shared by the public and private entity. If the contractor bears the burden for preexisting conditions, the risk could limit the rating. In some instances, the municipality bears all responsibility for environmental risks and will cover the costs associated at the various stages of buildout. Fitch’s concern is for the overall viability of the project: how unexpected environmental costs will be paid for, are there adequate reserves and insurance, or are the risks assumed by the party best able to handle such issues.

FITCH BASE-CASE AND STRESS-CASE SCENARIOS

To assess the ability to repay debt in a full and timely manner, Fitch will first evaluate the economic profile of the project and then layer onto it any legal, financial and policy constraints. To accomplish this, Fitch will initially design base and stress cases solely based on economic factors that incorporate reasonable scenarios that can occur based on Fitch’s experience with the sports industry as a whole and with similar projects. As an illustration, Fitch provides some guidance on how we might design these cases in the matrix … [that follows]. While the appendix is largely a general guide, tailored assumptions may be necessary based on local experience and broader legal, political, economic and financial considerations. The application of each of the factors identified will be a function of the type of the sports facility (new construction or facility with an operating history), the level of conservatism in key finance plan assumptions and the level of financial flexibility maintained.

For each factor, Fitch identifies an analytical approach and a range of possible adjustments. The level of adjustment within the identified ranges will be a function of the nature of the project and its risk profile, which incorporates service area analysis, historical franchise operations and the league framework, as well as Fitch’s assessment of the conservatism or aggressiveness built into the plan of finance provided. Fitch will then layer noneconomic factors to finalize our base and stress cases. Generally, Fitch’s base case will be more conservative than the base case provided by the entity, as Fitch’s base case seeks to establish a scenario that is highly probable under normal conditions. For example, Fitch’s scenarios eliminate any built-in optimism in assumptions with future attendance levels and any additional revenue assumptions, including higher concession, novelty, parking and ticket revenues. Fitch’s stress case then seeks to assess the ability of the structure to withstand a combination of severe, but reasonably probable, stress situations while still paying debt service on a full and timely basis.

The level of financial flexibility that remains after the application of the stress test to absorb further downside events will be an important driver of the facility’s debt rating. Facilities with minimal remaining flexibility will at best achieve low investment-grade ratings. Facilities with higher levels of remaining flexibility and strong structural enhancements may be able to achieve higher ratings, although they will be generally capped in the ‘A’ category.

APPENDIX TO SPORTS RATING GUIDELINES

Sports Financing in Europe

A small number of European football-related (often referred to as soccer in the United States) financings have been completed, mostly via private placements with banks or with institutional investors (frequently in the U.S. market), with the most notable public financing being that for Arsenal Football Club (a soccer club in the English Premiership League) in 2006. In order to understand the importance of relegation risks and other credit factors in European football, as compared to U.S.-based sports, it is necessary to understand how the English Premiership League system and other European counterparts operates. Although all of the specific features of the English Premier League are not necessarily common across the other European leagues, Fitch’s approach to analyzing key credit factors serves to illustrate the differences and specific risks addressed to transactions in Europe.

Because the role of European sport leagues differs significantly from the role of those in the United States, Fitch does not need to rate the league in order to rate a sports transaction. While the rules of the leagues in terms of broadcasting revenue distribution, financial control and sporting sanctions in case of financial difficulties will be reviewed, there is no concept of a league-related rating cap for European football transactions. However, given that Fitch compares sports-related credit ratings across various countries and the risks of relegation in Europe, Fitch notes that European soccer ratings may be limited to rating ceilings based on the league fundamentals analyzed in U.S. sports transactions.

Leagues

Arguably, European football is the most highly developed and popular sport in Europe. The Barclays English Premier League (the top league in England), Serie A (the top Italian Soccer League), Liga de Futbol Profesional (commonly known as La Liga, the top league in Spain), the Bundesliga (the top league in Germany) and Ligue de Football Professionnel (the top league in France) are widely regarded as the top five leagues in Europe. Each league operates and competes within their respective country, as well as in competitions across Europe.

Qualification for the two major European competitions, the Union of European Football Association (UEFA) Champions League and UEFA Cup, is available to clubs finishing in the top 4–8 spots in the league (the exact number depending on the size of the league and past performance of its clubs in the European competitions). At the opposite end of the scale, clubs can be relegated to a lower league if they finish the season in the bottom two or three spots in the league.

This structure has the effect of making virtually all games have some importance, whether for the top clubs seeking to win the league, the middle-ranking clubs seeking to qualify for European competition and the extra income that brings or the bottom clubs seeking to avoid relegation. This apparent lack of a widely competitive league structure has not detracted from the popularity of the game, which continues to improve annually, given Fitch’s observation of attendance levels across Europe. This is undoubtedly partly a result of increased interest in the pan-European competitions, where there are no dominant teams or countries.

Relegation

The major European soccer leagues practice a system of promotion/relegation. This is the key difference in league structures between the U.S. and European soccer leagues and raises unique credit risk concerns. Relegation is the process by which poorly performing teams at the bottom of league standings are demoted to a lower division and replaced by top teams in the next lowest division. This performance-related risk can have significant implications on two fronts. First, broadcast rights fees can be dramatically different from one division to the next, creating a greater degree of uncertainty with regard to revenue flows. Second, attendance figures will be affected, as fan interest is a function of the level and quality of competition. Some leagues provide an element of compensation for relegated teams in the form of a “parachute payment,” payable for two years in the case of the English league, to offset the effect of lower revenues (mostly media), which may not be immediately fully reflected in lower player salaries. Despite the parachute payments (which are not common to all European leagues), relegation is a considerable rating stress scenario for which Fitch seeks reassurance that the relevant club would have adequate financial resources to meet its debt payments.

Locally Generated Revenues

Ticket sales are widely viewed as the most stable revenue source, but they can vary significantly between the largest clubs with stadium capacity of more than 70,000 to the smallest clubs with stadium capacity of 20,000. Historically a club’s revenues would have been principally generated by ticket sales to the local community, in addition to a small proportion of sales to traveling fans. The increased influence of television broadcasting rights, sponsorship, advertising and retail sales via club Web sites has changed the revenue mix significantly, but the importance of local support is a key rating factor and has historically contributed to a signifi-cant proportion of total club revenues.

Given the large dependence on ticket revenues, Fitch will review the history of a football club over the past 10–30 years, with particular focus on its league position and the effect on ticket prices and the stadium occupancy rate. The history of the club in terms of ticket sales and prices in different league positions will be taken into account in applying stresses, but recent evidence of the effect of relegation may be unlikely for one of the leading clubs. In this case, stresses will be based on the experiences of other clubs relegated in more recent years. Some clubs, which are notable for having a very loyal local following, may be stressed less in terms of match attendance.

Similar to U.S. transactions, Fitch will generally use a historical occupancy/attendance average of the stadium as a floor for attendance and create a stress scenario that will apply a steady fall in the premier league position from its most recent performance and, given the long term of these transactions, a relegation scenario one or more times during the life of the transaction for one or more years on each occasion. Fitch will then assess the effect of declining ticket revenues on the transaction’s ability to service the debt. A club that has occupied a high league position over a long period of time or has never been relegated into a lower league will provide guidance in assessing the future financial performance of the club.

Television Contracts

Although generally a less important source of revenue than ticket sales, certainly as compared with U.S. sports, television/media contracts are still crucial to the financial success of a club. Contracts have historically been renewed every 3–4 years, and recent experience has been that significant increases have been achieved with new contracts. This provides Fitch some comfort that future negotiations would be positive, although, there is no certainty the value of future broadcasting contracts will be of equal or greater value. Consequently, Fitch generally will assume minimal, if any, increases in renewal amounts.

The split of media revenues varies from country to country. In England, approximately 50% of the revenues is shared equally across the top 20 premier league teams, 25% is shared by reference to the number of games of a particular club that are televised (inevitably a larger share for the more successful and more widely supported clubs) and the remaining 25% is split by league position on a sum of the digits basis (i.e., the top club receives 20/210th, the bottom team 1/210th). Similar to ticket receipts, there is a built-in bias toward the larger and more successful clubs, thus consolidating their ability to remain larger and more successful.

The broadcasting rights in English football are contracted on a pool basis (i.e., the contracts are negotiated by Football Association [FA], the governing body, on behalf of all the clubs). The revenue is then shared among Premiership League teams according to the above formula. However, as noted, there is a built-in bias toward the larger clubs. This is regarded as a necessary in order to prevent each club from negotiating its own contracts and creating a more size-biased distribution.

Fitch notes the key difference in the distribution of national broadcast revenues in Europe, as compared with the United States, is that the four major sports receive an equal distribution of national broadcast revenues. While this provides some revenue certainty, locally generated media outlets can vary between large and small market teams. Given this key difference, Fitch typically assumes that a club’s share of broadcasting revenue decreases in line with the formula set out above as it moves down the league table. Fitch will create a stress scenario by applying a steady fall in the premier league position from its most recent performance and, given the long term of these transactions, a relegation scenario one or more times during the life of the transaction and for one or more years on each occasion. Again, the extent of the decrease will be based on the experience of relegated clubs in the past. Fitch will then assess the effect of media and other revenues on the transaction’s ability to service the debt.

Sponsorship and Advertising Agreements

The wide appeal of football has seen a huge growth over the past decade in terms of advertising and sponsorship revenue. Similar to the growth in broadcast contracts, sponsorship and advertising agreements, for clubs in comparable league positions, have experienced similar growth. While sponsorship and advertising agreements are usually negotiated on a club-by-club basis with clubs with the biggest fan bases and stadiums commanding the best deals, sponsorship and advertising agreements are key to each club’s financial existence.

Other revenues, such as merchandising, have historically followed similar patterns, but many clubs have developed more sophisticated approaches to exploiting the potential for increasing match day revenues and sales via the Internet to, in many cases, a worldwide audience. The clubs with the bigger grounds also have the ability to use their corporate hospitality facilities on nonmatch days for conferences, weddings, etc. Only this latter source is likely to be delinked from on-the-field performance.

Fitch generally takes a similar approach to creating stress scenarios for sponsorship and advertising, as compared with ticket sales and broadcast revenues, whereby a team performance and league standings are analyzed. Stressed sponsorship revenues will typically follow the terms of the contracts, which often contain reductions for poor performance. In the event that a sponsorship contract expires during a period of relegation, Fitch would assume renewal at a stressed rate. Other commercial revenues that are likely to be directly linked to team performance will be stressed accordingly.

Player Salary Structure

As noted earlier, there are no salary restrictions in European football. However, salary costs as a percentage of overall turnover are a standard measure of financial prudence, with 55% being the average for an English club. There are, of course, anomalies, particularly where the club has been purchased by a wealthy individual who is prepared to buy success. The notable example is Chelsea in the English League, which was purchased by Roman Abramovich, the Russian oil magnate, in 2003. Since then, the club has purchased several players at huge transfer fees and has the highest wage bill in the country.

In terms of costs, Fitch will review player contracts to see whether a club has some flexibility in managing the overall cost (e.g., by staggering contract maturities so as to be able to take the opportunity not to renew a contact for a particularly expensive player). In reality, the better players will seek a transfer to a more successful club, especially in the event of relegation. So, the decline in costs is, to a degree, inevitable even with careful management. However, Fitch will always assume some lag relative to the decline in revenues. Most other costs are seen as independent of league position, so they will not typically be adjusted.

In addition to adjustment to player salaries when a club is relegated, Fitch will also look for features that restrict the net transfer spend (i.e., cost of new players less proceeds from players sold) and, even in a period of strong performance, restrict the use of transfer fees received for football-related assets, usually new players. In the absence of these features, further stresses will be applied.

Relationship Between League and Players’ Unions

Players’ unions exist within European sports leagues, but their role has little overall financial effect because it tends to be focused on protecting players against harsh disciplinary measures (usually by the league rather than an individual club) and securing appropriate compensation in the event of career-threatening injury. There have been no incidents of strike action in recent years, and Fitch generally views this as a strength of European soccer transactions. Furthermore, given the minimal risks associated with work stoppages, stress scenarios for a club or stadium transaction generally do not incorporate a work stoppage, where, given the history of work stoppages in U.S.-based sports, are applied.

Role of League in Team Financial Matters/Debt Limits