CHAPTER ONE

INTRODUCTION

In the United States and in professional sports around the globe, the individuals or entities that own various sports enterprises have been instrumental in setting the direction of the sports business. As long as there have been professional sports, there have been investors motivated by profits, public attention, winning, and community impact. As described in Don Kowet’s 1970s classic The Rich Who Own Sports,1 chariot races in ancient Rome were structured as a league, with corporations owning each of the four teams that competed at Circus Maximus—the Whites, Blues, Reds, and Greens—whose drivers dressed in the appropriately colored tunics. As the Roman Republic became the Roman Empire, the popularity of the races led to an expanded schedule—more races—and the gradual addition of 12 teams, with expansion fees in the millions of sesterces (the currency of the day). Owners of the chariot teams ran a profitable business.

The United States has seen several generations of professional team owners. The “original” generation of owners was largely composed of men (and it was all men) who had playing and/or coaching backgrounds. They typically wore multiple hats—owner, general manager, and coach, for example. The National Football League (NFL) had George Halas of the Chicago Bears and Curly Lambeau of the Green Bay Packers; Major League Baseball (MLB) had Connie Mack of the Philadelphia A’s, Charles Comiskey of the Chicago White Sox, Clark Griffith of the Washington Senators, and John McGraw of the New York Giants.2 Other owners bought teams with the goal of making their team the focus of their entrepreneurship. The team was their business. Though not inconsequential, their monetary investments in their teams was paltry by today’s standards, and their ownership occurred during the start-up days of their leagues—an era marked by franchise and league instability. Without the determination and foresight of these owners, the leagues would not have survived.

The second generation of league owners was comprised largely of men who had made money in other industries and whose interest in sports led them to purchase a franchise. Multimillionaires such as Ray Kroc, Ewing Kauffman, Charlie Finley, and Gene Autry invested part of their fortunes in MLB teams. The second generation of owners blazed a trail for the current, third generation. This third generation is marked by individuals who have accumulated vast fortunes through outside business interests and who have purchased sports organizations for any number of different reasons—from business to pleasure. Corporations are also an important part of this third generation, with entities such as Red Bull, Comcast, and Cablevision joining the ownership ranks (Table 1). These corporations look to use their sports holdings to improve their core businesses.

The individual equity ownership model of sports organizations can take one of two forms. The first form involves a single, independently wealthy owner, such as “new school” owners Dan Snyder, Mark Cuban, Paul Allen, and Jeffrey Lurie, who can take either a passive or active role in the club’s decision making. The owner’s role may change over time as he or she becomes less or more interested in team operations. The second form involves a group of individuals who pool their resources to acquire ownership of the team. League rules usually require that one individual be deemed the majority owner and/or specify that one individual be labeled as the final decision maker. For example, in the NFL the majority owner’s family must have a 30% stake in the team; in the NBA the requirement is 15%. An investment syndicate document typically outlines the rights and responsibilities of each investor. Although this model can be quite successful—witness the Boston Celtics “Banner 17 LLC” group of Wyc and Irving Grousbeck, Stephen Pagliuca, and Robert Epstein—it can be fraught with danger if the members of the syndicate develop philosophical or personal differences. The demise of the Atlanta Spirit LLC group and the antagonistic relationship between the Liverpool Football Club’s owners Tom Hicks and George Gillett are instructive.

Table 1 List of High-Profile and Publicly Traded Corporations that Own Sports Franchises

| Company | Symbol | Teams |

Cablevision Systems |

CVC |

NY Knicks, NY Rangers |

Comcast Corporation |

CMCSK |

Philadelphia 76ers, Philadelphia Flyers |

Liberty Media Corporation |

LCAPA, LCAPB |

Atlanta Braves |

Nintendo Company |

NTDOY |

Seattle Mariners |

Rogers Communications |

RCI |

Toronto Blue Jays |

Source: Based on records of the Sports Business Resource Guide and Fact Book (2009).

League operators have long preferred to work with individuals who they can look directly in the eye at a meeting and with whom they can make decisions on the spot. League commissioners and owners prefer to deal with individuals rather than corporations and their often unwieldy boards of directors. Leagues want to make decisions now, not when the schedules of two dozen corporate boards allow or, worse yet, those of thousands of shareholders. However, with the exception of the NFL, all leagues now allow teams to be owned by both individuals and corporations, despite the fact that the latter is operationally less desirable. Allowing corporate ownership provides the leagues with greater access to capital markets (i.e., the pool of potential buyers). This helps keep franchise sale prices high.

Although it is debatable whether the evolution from individual to corporate ownership is good or bad for the sports industry, there can be no doubt what is motivating this change: money. Although owners have always been wealthy, escalating franchise prices and operating costs have made ownership by the individual “moms and pops” that embodied the first and second generation of owners more difficult. The game has become too risky and expensive for many of them to play. In the United States, estate planning has also led to the divestiture of sports franchises by individual owners. Even when individual owners have remained, the rationale for their involvement may have changed. Although some venerable first- and second-generation owners remain, such as the descendants of the Mara and Halas families of the NFL’s New York Giants and Chicago Bears, respectively, the new breed of individual owners such as Paul Allen, Phil Anschutz, Bob McNair, Jerry Jones, Ted Leonsis, and Jeff Vanderbeek has infused professional sports. Having representatives from all three generations of ownership creates an interesting dynamic within the ownership ranks of each league.

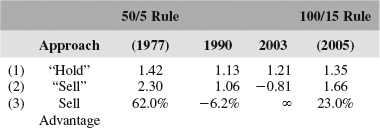

A number of taxation issues are particular to the sports industry. These issues arise primarily upon the transfer of a sports franchise and involve the accounting concepts of amortization and depreciation. A significant part of the acquisition of a professional sports franchise involves intangible assets, such as the league membership agreement, the facility lease, contracts with season ticketholders, media contracts, and player contracts. The preferential treatment that professional sports franchises receive under the federal tax code—especially with respect to player contracts—is controversial, because it provides their already wealthy owners with a lucrative tax shelter for a period of years after the purchase transaction. The resulting tax benefits associated with ownership of a professional sports franchise help to keep the marketplace robust. Along with the consumption value of team ownership and the opportunity for operating profits and overall capital appreciation, the generous tax treatment of professional sports franchises encourages investment in this industry. Thus, it is important for prospective and current owners to understand the applicable taxation principles. In this chapter’s final excerpt, Coulson and Fort provide an excellent overview of these tax issues.

In addition to the financial benefits that can result from the ownership of professional sports franchises in terms of the possible generation of operating profits, tax benefits, and asset appreciation, a very high consumption value is involved as well. Individual owners have long received significant psychological benefits from ownership, such as boosted egos, publicity, access to athletes and other powerful individuals, the chance to be a “winner” on the field, retaining or enhancing a community asset, membership in an exclusive fraternity or club, and the fun of being a real-life “fantasy team” owner. The motivations of some individual owners have changed in recent years, as there is an ongoing shift in focus to the synergies that ownership can provide. Some individuals, such as former owners Bruce Ratner of the NBA’s New Jersey Nets and Victor McFarland of Major League Soccer’s D.C. United, are motivated by the real estate opportunities surrounding the playing facility. The team serves as a means to accomplish the end goal of maximizing the returns on the larger real estate play. For others, team ownership provides valuable networking opportunities. Bob Johnson, the former owner of the NBA’s Charlotte Bobcats, explained it this way:

It’s not the sports side of me that drives ownership, it’s the business side. Owning an asset like this creates the potential for opportunities beyond the business itself. There are opportunities to develop relationships with other team owners. These are entrepreneurs who like to do things outside of the box. There may be other things I can do with [Dallas Mavericks owner] Mark Cuban or [Denver Nuggets owner] Stan Kroenke. It’s just a good club to belong to.3

Other, lower-profile owners use the team to increase their visibility in the local marketplace. Robert Nucci, the owner of the now defunct Arena Football League’s Tampa Bay Storm, said, “The investment is in the community and in the value of the franchise. By owning this franchise, you’re very involved in the community. Your business becomes more well-known, your overall connections increase. You meet people you haven’t met before. I think it’s a very good investment.”4

Some owners are motivated by a desire to win on the field. Owners are usually very competitive individuals, and this competitive nature has helped them to accumulate the vast amount of wealth that it now takes to acquire a professional sports franchise. The ability to compete for a championship provides them with a high-profile outlet for their competitive streak. Roman Abramovich, the Russian billionaire oligarch and owner of the Chelsea Football Club, said, “The goal is to win. It’s not about making money. I have many much less risky ways of making money. I don’t want to throw my money away, but it’s really about having fun and that means success and trophies.”5

Despite having the business acumen that it takes to accumulate enough wealth to afford a professional sports franchise, a number of owners have struggled to be successful in sports. Donald Trump, the owner of the New Jersey Generals of the long-defunct United States Football League (USFL), once said, “I watch the owners suffer. They have businesses and they’re very successful, but when it comes to sports, it’s like they lose a lot of business judgment.”6

It is important to understand why this is the case. The sports industry is an industry of nuance. First, entrepreneurs in other industries are motivated by one thing—making money. However, entrepreneurs in the sports industry are pursuing victories in addition to profits. Craig Leopold, the owner of the NHL’s Minnesota Wild, has stated:

Owning a sports franchise, I would say, is a departure from conventional wisdom. It’s a different business, a different business model, although you use the same principles of management. That is, you get the best people that you possibly can and you let them do their jobs. But ultimately the end game is different: You’re trying to win something, and the value of the asset is getting larger and larger even though your losses may continue. That’s not a normal business model.7

Robert Kraft, owner of the NFL’s New England Patriots concurs:

I learned early on that you come in as a fan, but there’s no on-the-job training for owning an NFL franchise. You have to get in it and get roughed up by it. You go through a learning curve, understanding the nuances of the business that are different. At the same time, I think it’s important that when you run and manage a franchise, that you use the same core values that you use in your other businesses. You always have to decide what is right for you and your system, develop a strategic plan and follow it even when things don’t go your way. It’s pretty cruel in the short term when you lose and things don’t go right, but as long as you believe you have a good plan, you have to stick with it and back the key people in your system.8

Second, most owners are not used to losing in their entrepreneurial ventures, and like most other entrepreneurs, they do not like to do so. Owners do not buy sports franchises envisioning that they will lose a lot of games. However, the binary nature of sports means that every game has a winner and a loser. There is a lot of emotion associated with the games, and it can be very difficult to separate this emotion from logic, especially when the team is losing a lot. Mark Richardson, the former president of the NFL’s Carolina Panthers, explains it this way, “Until you get into it, I don’t think you truly understand it. You don’t realize the impact (an NFL team) has on your community. You don’t understand the depth of emotion that goes with the fans and the team. You don’t realize how hard it is to win.”9 Perhaps the best way for the owners to keep from making emotional decisions is to let others handle the daily operations of the franchise. In many cases, this is contrary to how many owners run their nonsports businesses, and for some it takes the fun out of owning a team. But the NHL’s Chicago Blackhawks chairman Rocky Wirtz agrees: “You realize tomorrow is a new day, so you can’t let your emotions control your better judgment. The owner needs to not get in the way. Too many times the owners in sports tend to let their egos get ahead of them and that is not good. You have to run this as a business.”10

Third, being an owner of a professional sports franchise is a high-profile position that is dissimilar to what most owners have experienced in their other endeavors. Mickey Arison, owner of the NBA’s Miami Heat, explains:

Before you get into it, you don’t realize how high-profile it is and how much focus there is on you personally. I’m better known in the community for the team than [for] Carnival [the cruise line that he owns], and that doesn’t make a whole lot of sense when you think about it. But the reality is that before I owned the team, I could go out to a restaurant and walk around town and people didn’t know who I was. That changed dramatically, and even more so more recently.11

Although some owners enjoy the publicity and thrive on it, others are far more reluctant to spend time in the spotlight. When John Moores owned the San Diego Padres, he once said:

The worst part of owning the club is the public part of it. It’s just tacky. It’s a little bit of a freak show. But being held up to public scrutiny just comes with the territory of owning any baseball team or public enterprise. It means people care. What would disturb me would be the opposite. If you’re not criticized, it means people don’t care. Then I would really worry. But people do care. They care a lot. People in this town care a lot about the Padres, and I’m glad they do.12

In recent years, the ownership entity has evolved from the gritty, individual model embodied by Art Rooney and George Halas to the presence of both individuals and corporations—particularly media, entertainment, and communications companies—looking for synergies to exploit. It seems that the trend towards corporate ownership is waning, with many of the media, entertainment, and communications companies selling their sports holdings in recent years. Indeed, 10% of all teams in the NBA, MLB, NFL, and NHL are owned in the majority by corporations. Corporations own a minority share of 16% of the teams in the NBA, MLB, NFL, and NHL. A recent count shows that 12 MLB, NBA, and NHL teams are owned by corporations. Rogers Communications, Liberty Media, Comcast, and Cablevision are among the media companies that are involved in the ownership of sports franchises. Traditionally, ownership of professional sports franchises is attractive to corporations with interests in the media, communications, and entertainment business, because sports team programming has significant content value due to the franchise’s strong audience loyalty and brand visibility.

Viewing sports franchises as entertainment assets, corporations have attempted to use them to garner additional revenues through the team’s playing facility and media rights. In theory, the ownership of the team and its playing facility and programming rights enable the corporate owner to enhance the team’s value through the exploitation of a wide range of synergies, including cross-promotional opportunities, the creation of additional distribution outlets, and higher visibility in the marketplace, as well as risk reduction and cost savings through economies of scale. For this reason, as revenues and costs grow larger and values keep increasing, theoretically the number of corporate owners should increase. However, this strategy has not been successful for every corporation that has attempted it, and nationally focused media companies have trended away from sports ownership as a result. It is likely that corporate owners with a local or regional focus will be more successful than those with a national or global focus. Politician Tip O’Neill’s statement that “all politics is local” seems to apply to corporate ownership of professional sports franchises as well.

Some notable flameouts have occurred among nationally focused corporate owners. Former team owners Disney, News Corporation, Tribune Company, and Time Warner abandoned their “sports strategies,” at least partially because they were unable to capitalize on their ownership of professional sports franchises. Disney’s failure is likely attributable to its inability to effectively capture the media-related revenues available through its sports franchises, which resulted in the company incurring a $100 million loss during its ownership tenure of the Anaheim Angels MLB team and Anaheim Mighty Ducks NHL team. To Time Warner, the value of owning professional sports franchises was in its ability to charge national advertising rates for the broad cable distribution of local team broadcasts via its TBS Superstation. When this value diminished as the company grew from a local broadcasting interest to a global venture through a series of mergers and acquisitions, and investor pressure grew for the company to reduce its debt load in a difficult economy, Time Warner withdrew from ownership of its sports franchise holdings. Ironically, the Atlanta Braves were sold to another media company, Liberty Media, as part of a larger stock swap transaction between the companies. Liberty Media is widely expected to sell the team after the tax requirements associated with its acquisition of the team are satisfied. News Corp. acquired the Dodgers from its longtime owners, the O’Malley family, in 1997 for a then-record price of $311 million. In doing so, the company was able to secure the team’s broadcasting rights far into the future. Beyond that, however, the Dodgers were never a great fit for the Fox Entertainment Group, the News Corp. subsidiary that operated the team. The team was never part of its parent company’s core business, and the managerial skill of the parent company’s executives was misplaced when focused on the team side. The Dodgers became lost within the larger entity, and as the team struggled to make the playoffs and began to incur substantial operating losses, News Corp. soon tired of owning the team. When the parent company made the additional acquisition of satellite operator DirecTV for over $6 billion, the Dodgers and its related properties were sold to real estate mogul Frank McCourt, in part to help finance the purchase.

A final hurdle facing large corporate entities that own sports teams is investor and analyst pressure. When the parent company is facing financial difficulties, investors and analysts often place pressure on the company to return to its core businesses. The team is rarely part of that core. In addition, the revenues that are generated by sports franchises do not create regular quarterly earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization (EBITDA, a measure of cash flow); instead, revenues are highly seasonal in nature and vary significantly from quarter to quarter. However, public companies are under quarterly pressure to report EBITDA growth; thus, sports teams are not necessarily a good fit for publicly traded corporations.

With the exception of a handful of teams, local sports franchises do not have much impact on a national or international level, where audience loyalty is unlikely to be strong and cross-promotional opportunities limited. Locally focused corporations avoid these problems and can retain the additional revenues that are available through the ownership of professional sports franchises. This is especially true if the corporation is the dominant cable provider in the local marketplace. Companies such as Comcast (owner of the Philadelphia Flyers and 76ers) and Cablevision (owner of the New York Rangers and Knicks) can realize the benefits of vertical integration. By owning the team, its playing facility, and its local media distribution channel, the company captures the lion’s share of revenue generated by the team. It is able to dominate the local marketplace, where fans are most passionate about the local teams and can be most effectively monetized.

In addition to this mix of old-school and corporate owners are anomalies such as the Green Bay Packers, a franchise long held in a public ownership form and a grandfathered exception to the NFL’s rules against corporate ownership. In the 1980s and 1990s, a smattering of other public offerings cropped up as well. The public-offering structure has provided a cash infusion to existing sports enterprises, including several North American franchises and numerous European soccer clubs. The investment merit of these offerings is somewhat dubious; they turned out to be outlets for fan affinity rather than opportunities for real financial returns.

Some private equity (PE) investment has occurred in professional sports. Although there seems to be some trending away from PE investment in sports, such investment has been significant in value when it has occurred. PE investments in major professional sports leagues have presented a number of problems. Operating within a sports league environment is not a great fit for the traditional PE model of purchasing a distressed property, slashing costs, increasing short-term revenue, and exiting for large profit, typically after a 5-year period. The challenges for PE returns are daunting. Growth areas are limited by league rules covering everything from the team’s exclusive and limited geographical territory to marketing prohibitions. Existing long-term local media and sponsorship deals also limit growth opportunities. Cost reduction is difficult because of the presence of collective bargaining agreements negotiated on a leaguewide basis with the players’ unions that establish team and individual player salary floors. An additional concern is whether PE firms are too focused on the short term to be effective team owners. Finally, the exit strategy can prove difficult. Given the aforementioned restrictions, the appreciation of the sports asset may not increase substantially in the window preferred by the PE firm. Thus, it may be that ancillary sports deals are somewhat better suited to PE investment. Indeed, firms such as IMG, Route 2 Digital, Falconhead Capital, and Spire Capital have invested in entities such as rodeo, beach volleyball, cricket, and a number of sports media companies. Minor league baseball and hockey, indoor football and soccer, and lacrosse may offer additional investment possibilities.

Several American sports leagues have recently adopted the single-entity structure. MLS was the first entity to use this model, in which an entire league is controlled by a single operating company. Investments are made in the company, rather than in a particular franchise. This format was developed to avoid the self-destructive behavior displayed by owners in other nascent sports leagues whose desire to win has led them to pay more than they could afford for athlete services. This behavior contributed to the demise of these leagues, because so many teams went out of business that the leagues could no longer survive. By adopting a single-entity structure, competitive bidding among owners for players is eliminated, and a major cause of league failure is sidestepped. In addition, this structure allows sports leagues to evade the application of antitrust laws in management–labor disputes.

Following the lead of MLS, most new leagues have since adopted this operating structure. Despite its strengths, the model may not prove to be an effective method of running a mature league. The single-entity structure places a disincentive on individual investors to engage in entrepreneurial behaviors, because the benefits of such tactics are likely outweighed by their costs. The whole may be weaker than the sum of its individual parts. More on the single-entity model can be found in Chapter 2.

As the sports world has become “flatter,” there has been an influx of foreign ownership in sports leagues throughout the world. While the NBA’s New Jersey Nets were purchased by Russian oligarch Mikhail Prokhorov in 2010, this has been especially prevalent in the English Premier League (EPL), widely regarded as the top soccer league in the world. English clubs Manchester United, Aston Villa, Liverpool, Arsenal, and Derby County are controlled by Americans; Manchester City and Portsmouth (at the time of this writing) are owned by investors from Abu Dhabi and Saudi Arabia, respectively; Fulham is owned by an Egyptian; Chelsea is owned by a Russian; Birmingham City is owned by someone from Hong Kong; and Sunderland is owned by an Irish consortium. The global popularity of the EPL and the more relaxed league rules concerning revenue opportunities and growth make it appealing to foreign investors. Similarly, an entire league, the Indian Premier League (IPL), played its second season in 2009 in South Africa rather than India. The season was moved largely for security reasons, but the action is illustrative of the shrinking sports globe.

The readings that follow examine these various ownership models and the business issues impacting individuals involved in each. There is an emphasis on the functionality of each model. Beyond impact and functionality, the valuable lessons come from understanding who the successful owners have been and who the most successful owners of the future might be.

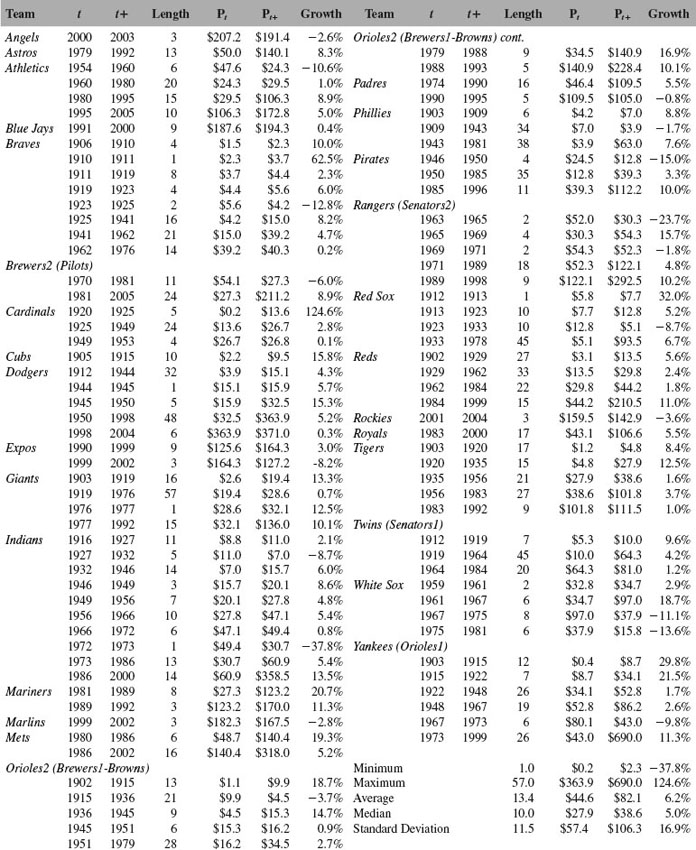

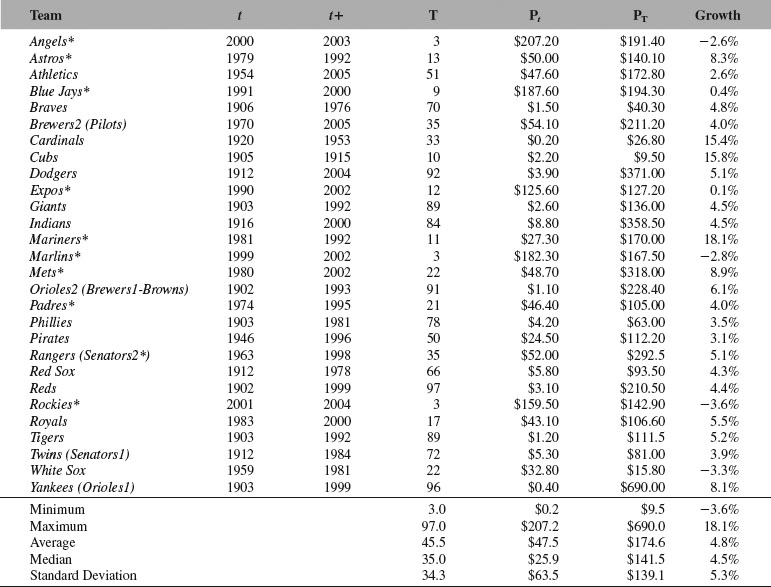

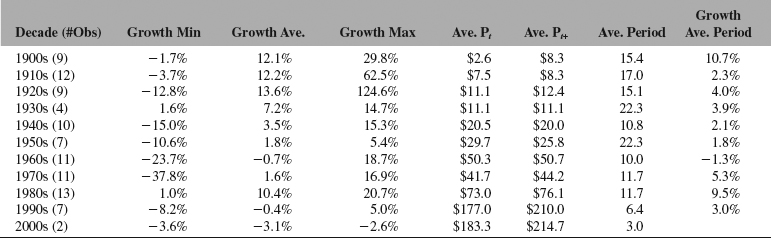

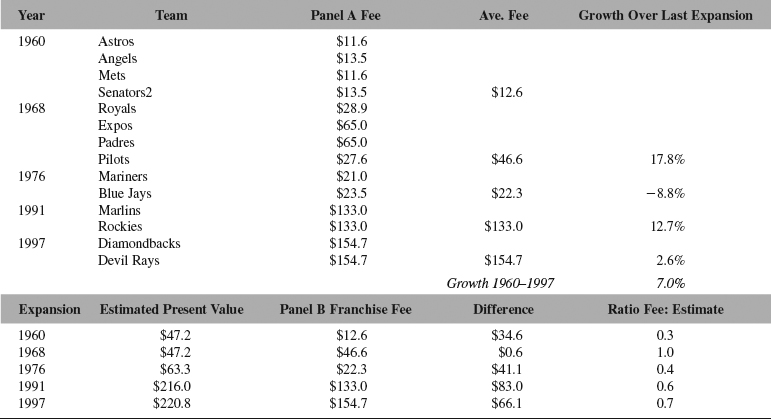

The chapter opens with an excerpt from Quirk and Fort’s classic, Hard Ball: The Abuse of Power in Pro Team Sports, which touches on ownership history and also provides an overview of modern-day owners. The excerpt also focuses on how these owners fit into the modern-day sports league. This is a discussion that will be carried out in more depth in Chapter 11, “Sports Franchise Valuation.” Note that the excerpt discusses the “why” of ownership, both in monetary and nonmonetary terms. Noted sports economist Andrew Zimbalist is excerpted from next, providing an excellent overview of the reasons that investors seek out professional sports. Rod Fort examines the value of owning an MLB team in the third selection. The fourth and fifth excerpts focus on initial public offerings (IPOs). This format, which has received a good deal of attention, seems to be more of a novelty than an important long-term business model. These are faceless owners, but similar to the broader corporate model used for raising funds for business success. After a brief flurry, it seems that the use of this novel approach to ownership has fizzled in North America, although the model endures in Europe.

Among the related readings in other sections of the book, three might be of particular interest. In Chapter 8, “Media,” there is a discussion of vertical integration. In Chapter 4, “Emerging and Niche Leagues,” a selection focuses on the single-entity model of league operation. In Chapter 18, “Race,” the excerpt from the article “Diversity, Racism, and Professional Sports Franchise Ownership: Change Must Come from Within” focuses on the diversity issue as it relates to ownership.

Notes

1. Random House, 1977, pp. 3–8.

2. Quirk and Fort, Hard Ball.

3. Phil Taylor (quoting Bob Johnson), “Franchise Player,” Sports Illustrated, May 5, 2003, 36.

4. Bruce Goldberg (quoting Robert Nucci), “So, You Want to Buy into the AFL? Here’s How,” Sports Business Journal, February 25, 2008, 18.

5. Alexander Wolff (quoting Roman Abramovich), “To Russia with Love,” Sports Illustrated, December 15, 2008.

6. Peter Fitzsimons (quoting Donald Trump), “Select Policy Pays off for Swans,” The Sydney Morning Herald, October 1, 2005.

7. (Quoting Craig Leipold), “The Daily Goes One-on-One with Wild Owner Craig Leipold,” Sports Business Daily, November 25, 2008.

8. Jim Chairusmi (quoting Robert Kraft), “Top of His Game,” The Wall Street Journal, December 2004.

9. (quoting Mark Richardson), “Panthers Celebrate 15th Anniversary in NFL Amid Ups, Downs,” Sports Business Daily, October 28, 2008.

10. (quoting Rocky Wirtz), “Chicago Sports Leaders Gather to Discuss Local Market,” Sports Business Daily, September 18, 2008.

11. John Lombardo (quoting Mickey Arison), “The Man Behind the Scenes,” The Sports Business Journal, April 30, 2007, 1.

12. Barry M. Bloom (quoting John Moores), “Moores Reclaims Active Role with Padres,” mlb.com, September 18, 2008.

PERSONALITIES AND MOTIVATIONS

HARD BALL: THE ABUSE OF POWER IN PRO TEAM SPORTS

James P. Quirk and Rodney D. Fort

The payoffs to a rich owner from owning a sports team might come mainly from the fun of being involved with the sport itself and with the players and the coaches, rather than from the profits the team generates. There is also the publicity spotlight that shines on the owner of any team—Carl Pohlad [late owner of the Minnesota Twins] is much better known in the Twin Cities for the Twins than for his Marquette National Bank…. And all of the fun and publicity is that much more intense when the team you own is a winner.

This view of owners as “sportsmen” ignoring bottom-line considerations has its attractions, and there have been owners who really seem to have fit this image—Tom Yawkey of the Boston Red Sox of the 1930s and 1940s is one who comes immediately to mind. Still, it pays to be a little skeptical. Billionaires don’t get there by throwing their money around recklessly—they tend to be the people who let someone else pick up the tab for lunch. As important as winning is to them, it might well be a matter of ego and personal pride that they manage to do this while pocketing a good profit at the same time.

A competing view of the owners is that, their loud protestations to the contrary, they actually are minting money from their teams’ TV contracts and high-priced luxury boxes and preferred seating licenses. According to this view, owners would very much like to field winning teams if there’s any money in it, but otherwise, they’re quite content to load up the roster with low-priced talent and have no qualms about moving the team if fans don’t flock to watch a second-division turkey.

Whatever view you have of the matter, there is no doubt that almost all of the huge amount of money that pro team sports generates, through gate receipts, TV income, stadium revenues, and sales of memorabilia, passes first through the hands of the owners. But how much stays there, and how much gets passed on in the form of player and coaching salaries, traveling expenses, administrative costs, stadium rentals, and the like? To answer this question authoritatively would require access to the books of sports teams and their owners. Unfortunately, we do not have that access. There are a few—the Boston Celtics, Cleveland Indians, and Florida Panthers—that are publicly traded businesses, so their revenues, costs, and profits are public information. [Ed. Note: All three teams have since been purchased by private individuals and taken off the public market.] But most sports teams are closely held businesses, organized as limited partnerships or subchapter S corporations, with no legal requirement to open their books to the rest of us. What we have instead is a set of estimates of income of the various sports teams, prepared on an annual basis since 1990 by Financial World [and now Forbes] magazine.

….

The first thing that is abundantly clear … is that, with just a handful of exceptions, pro team sports does not appear to be a terribly profitable business.

….

The figures seem to make mockery of the notion that owners are making out like bandits. At most only a few teams in each league are showing impressive book profits, and they are generally the ones that all of us would have predicted …

Another aspect of the financial picture of sports leagues … is the division between the haves and the have-nots ….

The large numbers of have-nots in baseball and hockey reflect the fact that winning is more important to the bottom line in these sports than in basketball or football. NFL and NBA teams derive most of their gate revenue from season ticket sales, whereas in baseball, walk-in ticket sales are an important share of the team’s gate revenues and are much more sensitive to the team’s won–lost record. In the NHL, there are the regular season and the “second season,” the playoffs. Playoff ticket sales are a critical part of any NHL team’s finances, so missing the playoffs almost certainly means financial problems for the team.

Add to this the fact that the value of local TV rights is sensitive to the playing success of a team and that local TV plays a larger role in baseball and hockey than in the other two sports. Thus, a larger share of revenue is sensitive to the won–lost record of baseball and hockey teams, which tends to increase the value of star players to teams, so that salary costs are adversely affected as well.

The large number of have-not teams also provides a clue as to why it was Major League Baseball and the NHL that experienced long debilitating work stoppages in 1994 and early 1995 [Ed. Note: and again in 2004–2005], with the have-not owners holding out for radical changes in the rules governing their leagues’ player markets….

What does this suggest about the profit orientation of team owners? We would argue that the pressures that free agency has imposed on the bottom line in sports, as indicated by operating income figures, have made it all the more important for teams to act like profit maximizers, ferreting out every possible source of revenue and exploiting it to the hilt, while paring away at costs with a vengeance. It is much more expensive to be a sportsman-owner today than it was in Tom Yawkey’s days, and this lesson is well known to everyone who owns a sports team. The drive for stadium subsidies and tax rebates and the hard-line stands in labor negotiations are just a few of the obvious consequences of the tightening of profit margins in sports.

Does this mean that we should be passing the hat again for Paul Allen …, or that we should erect statues to owners for their profitless task of bringing quality athletic entertainment to the masses? Well, maybe not. Let’s try to count some of the ways in which an owner can still break even or do better than that, even with an operating income that is negative or barely on the plus side.

First, it is commonplace for an owner to take on a salaried job with his team, as president or chairman of the board. It’s the owner’s team so he can pay himself whatever salary he wishes….

In the years when Calvin Griffith owned and operated the Minnesota Twins, it was widely reported that there were Griffith relations galore on the payroll of the team. There is nothing illegal or immoral about this, of course; in fact, to the contrary, it makes Griffith seem like what he in fact was, a very family-oriented person. However, it does mean that book figures on team revenues, costs, and profits for the Twins understated the income that the owner and his family derived from the team.

Second, more and more often, team owners today have complex financial interrelationships with their teams….

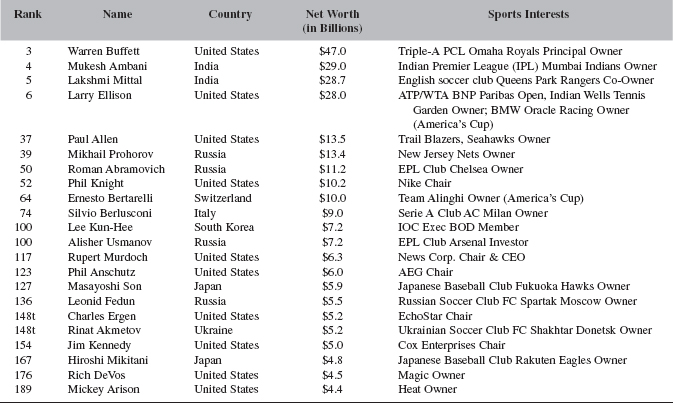

In the case of the Florida Marlins, when Wayne Huizenga owned the team, he also owned the stadium in which the team played as well as the Miami TV station that aired Marlin game telecasts. Into which of Huizenga’s several pockets did the stadium rental or the local TV revenue go? Questions like this have become much more than merely academic matters for the players in the NFL and NBA operating under salary cap rules, because those rules guarantee players a stated minimum percent of league revenues. League revenues will vary depending on whether the team gets the full market value of its TV revenues, or instead a part is transferred to the station, network, or superstation owned by the team owner. (See Table 2 for a list of the wealthy individuals that are involved in the sports industry.)

….

Third, ownership of a sports team provides tax sheltering opportunities that are not available to most other businesses, so that what appears to be a before-tax loss by the team can, in certain circumstances, be converted into an after-tax profit for the owner. The idea behind the tax shelter was one more contribution to the sports industry by the fertile and conniving mind of Bill Veeck, baseball’s greatest hustler and team owner. Back in 1950, Veeck was in the process of selling his Cleveland Indians team to a syndicate headed by his friend Hank Greenberg, the great Tiger outfielder. Veeck convinced the IRS that the purchaser of a team should be allowed to assign a portion of the purchase price of the team to the player contracts that the team owned, and then to treat this as a wasting asset, depreciating the contracts over a period of five years or less. That was an important bit of convincing, because the IRS already had in place rules allowing teams to write off as current costs signing bonuses, scouting costs, losses of minor league affiliates, and all the other costs incurred by a team in replacing its current roster of players with young players coming into the sport.

Table 2 Sports Interests Among Forbes’ Top 200 Billionaires in the World

Sources: “Forbes’ Sports Interests Among Forbes’ Top 200 Billionaires in the World,” SportsBusiness Daily, March 23, 2010. Billionaire rankings reprinted by permission of Forbes Media LLC © 2010. Sports information has not been validated by Forbes.

….

Owners typically plead poverty by quoting net operating losses as the value of the team. And, for people in their wealth class, even 7 percent does not seem like an extraordinary return. Harold Seymour, the eminent baseball historian, quotes Charles Ebbets on baseball operations: “The question is purely one of business; I am not in baseball for my health.” But before we agree that sports are not a high-return investment for rich people, let’s remember the other values of owning a team. Profit-taking can occur under the “other salaries” heading. Most of the rest of the costs may actually be revenues, or generate even larger revenues, in other nonsports business operations of the owners. Business and government associations made during ownership tenure are valuable. And there is, after all, the fun of owning a team. Given all of these benefits, a 7 percent rate of return generating $5 million annually after taxes looks pretty good to us. Now, if only we could come up with that initial $75 million….

A team can show a book loss, yet pay owner-management quite well while they run the team, generate many other values not captured in the team’s income statement, and end up as a very valuable commodity at sale time.

….

Finally, offsetting the bad news about operating income is the good news about the continuing increases in the prices of sports teams themselves. The capital gains that an owner gets from selling his team can more than offset the losses, if any, that the team has shown from its ongoing operations. In fact, this has been true in practically all cases involving recent sales of sports teams.

….

The fact that the market prices of teams keep going up, even while operating income figures remain at very low levels, raises the question as to whether what we are observing is a “bubble,” much like the bubble in California real estate in the 1980s. In a bubble, the current price of an asset is determined not by what the asset is expected to earn in the future, but by what people today think buyers in the future will be willing to pay for the asset. A bubble is fueled by the “greater fool” argument: “Sure, I know this house isn’t worth $300,000, but a year from now, I’ll be able to sell it to some other real estate speculator for $500,000 because he’ll be expecting the price the year after he buys it to be $600,000.” The price is what it is today because everyone expects a “greater fool” to come around tomorrow to take the item off your hands at an even higher price.

All that economists know for sure about bubbles is that, eventually, they burst, and it’s like the old game of musical chairs—whoever gets stuck with the overvalued asset at the time the bubble bursts has nowhere to get rid of it. There is a classic story about the stock market that goes something like this:

A broker touted a small company’s stock to a client and convinced him to buy 1,000 shares at $10 per share. A week later, the broker reported that the price was up to $12, and the client opted for another 1,000 shares. The price kept going up and the client kept buying for several more weeks. When the broker reported the price at $25 per share, the client said, “I’m not greedy. I’ll just take my profits now. So sell my shares.” There was a pause and then the broker asked, “To whom?”

If it really is a bubble that we are observing in the market for sports teams, the problem is that there isn’t any way to know beforehand just when the bubble will burst. Those unlucky people who happen to be holding title to the over-valued team franchises will simply have to eat their losses and live with them. But if it is a bubble, it’s been going on for quite a long time. Historical records of franchise sales in sports indicate that over the past thirty years or so [Ed. Note: from approximately 1970–2000], on average, NBA teams have been increasing in price at a rate of around 26 percent per year, MLB teams at around 14 percent per year, and NFL teams at around 22 percent per year.

The fact that the rates of increase in franchise prices in the 1990s, while in the double-digit range, still are lower than those in earlier years indicates that if there is a bubble in these markets, at least it is tapering off. Actually, over the period of the mid-1990s, investors were making a better rate of return simply “buying the market” with an indexed stock fund than were sports entrepreneurs with their high-visibility team investments.

Rather than being simply a bubble phenomenon, the continuing increase in team prices in sports and the capital gains being captured by owners no doubt reflect a range of factors at work in the sports industry. There are the “fun and games” and publicity aspects of ownership of a sports team. These have been increasing over time along with the media exposure that sports receives. The “spill-over” benefits of owning a sports team, those after-tax returns identified earlier that don’t show up as operating income for a team, have been increasing over time as well, and get reflected in higher team prices. And there is undoubtedly something of a speculative bubble present as well, a common belief among present and prospective owners that because almost no one in the past has sold a team for less than its purchase price, future capital gains are more or less assured.

In summary … the current owners of sports teams are, by and large, very wealthy individuals. But, with teams being as expensive as they are, ownership of a team is a significant investment, even for a wealthy owner. The returns to ownership, as measured by operating income, are below market rates of return from investments of comparable risk in all sports with the possible exception of the NBA. A prime reason for the weak operating income performance of teams is free agency and the continuing escalation of player salaries. This suggests that bottom-line considerations play a critical role in team decision making, perhaps looming larger for today’s owners than for owners of the past. On the one hand, this provides incentives for owners to act as aggressively as possible in attempting to exploit whatever local monopoly power the team possesses—if we don’t squeeze out every cent of money from local fans and taxpayers, how can we afford to compete with the teams that do? On the other hand, the concentration on the bottom line makes it more difficult for teams to act cooperatively as members of a sports league in addressing problems of mutual interest to all teams in the league. What team can afford to sacrifice some of its income for the “common good” in a world in which lots of red ink is waiting just around the bend for any team that loses a star player to injury or ticket sales to bad weather?

There have been exceptional owners such as Phil Wrigley, who refused to schedule night games at Wrigley Field when he owned the Cubs, to keep nighttime noise, traffic, and confusion out of the north side neighborhood of the park; and Ewing Kauffman, who heavily subsidized his Kansas City Royals when he was alive and then set up a committee of leading local citizens to operate and then sell the team after his death, to ensure that the team stayed in town. But everything about the current and historical record of pro sports suggests that if you are trying to understand what is going on in sports, your best bet is to assume that owners will be motivated by bottom-line considerations, however wealthy they are. Wayne Huizenga’s decision to sell off his Florida Marlins, one by one, and then the team franchise itself after the team won the 1997 World Series but reportedly lost $30 million at the gate, fits the mold nicely.

The contribution of owners to the problems of pro team sports does not arise, however, because they operate their teams to make money. After all, one of the fundamental reasons why we in America enjoy the living standards we do is that all those businessmen out there are free to operate to make as much money as they can. The argument in favor of a free enterprise, profit-oriented economy is that the way a businessman makes money is by producing the goods that consumers want, in the style and quantity that they want, at the lowest possible price. And if a businessman doesn’t do this, he should be prepared to be steamrollered by other businessmen who do a better and cheaper job of producing that product.

Once again, the problem with the sports industry is the fact that leagues operate as monopolies, so that team owners in sports are not subject to the same intense market pressures to perform well as if they had to face competition from rivals. The local monopoly power of teams is limited, of course, by the availability of substitutes. NFL football has to compete with the college game, with other pro sports such as the NBA and the NHL, and with alternative forms of entertainment. But, when combined with the monopoly power of the league it belongs to, the local monopoly power of a team is certainly significant, as evidenced, for example, by the success of teams in their campaigns for new, highly subsidized stadiums financed by cities and states….

SPORT AS BUSINESS

Andrew Zimbalist

I. INTRODUCTION

Unlike businesses in other industries, professional sports teams in a given league both compete against and cooperate with each other. The success of a league is, to some extent, affected by the degree of uncertainty of outcome of its contests and its seasonal competitions, or, stated differently, by the degree of balance among its teams.

Professional sports leagues also differ from other industries in the degree of public exposure they garner. The daily game results are reported upon extensively in the local print, audio, and video media, and discussed widely and passionately by millions of fans.

Do these unique features of sporting leagues lead team owners to behave differently from owners of other businesses? Preeminent sportswriter Leonard Koppett (1973, p. 11), writing in the New York Times Magazine 30 years ago, suggested that they do:

Club owners are not ordinary businessmen. To begin with, profit in itself is not the owner’s primary motive. Any man with the resources to acquire a major league team can find ways to make better dollar-for-dollar investments. His payoff is in terms of social prestige…. A man who runs a $100m-a-year business is usually anonymous to the general public; a man who owns even a piece of a ball club that grosses $5m a year is a celebrity. His picture and comments are repeatedly published in news papers known in every corner of his community…. This does not mean, of course, that ball clubs don’t seek profits … but the driving force is to be identified with a popular and successful team … and that motivation leads to important variations from ‘normal’ business behavior.

To be sure, many economists agree with this perspective. Peter Sloane, in his well-known piece on English football (soccer), writes:

It is quite apparent that directors and shareholders invest money in football clubs not because of expectations of pecuniary income but for psychological reasons as the urge for power, the desire for prestige, the propensity to group identification and the related feeling of group loyalty. (Sloane, 1971, p. 134)

He then goes on to quote a 1966 report on the English Football Association (FA) that found the objective of a club owner was ‘to provide entertainment in the form of a football match. The objective is not to maximize profits, but to achieve playing success whilst remaining solvent.’ Sloane suggests an owner-objective function with playing success, average attendance, health of the league, and minimum profits as its arguments.

At the time Sloane was writing, a large share of FA clubs carried payrolls that were above 80 per cent of team revenues and FA rules stipulated maximum dividend pay-outs to shareholders for the minority of teams that were publicly held.2 Indeed, it became commonplace among economists to associate FA club ownership with utility—rather than profit maximization. In a 1999 article, for instance, Stefan Kesenne and Claude Jeanrenaud state matter-of-factly: “The most important difference between the USA and Europe is that American clubs are business-type companies seeking to make profits, whereas the only aim of most European clubs so far is to be successful on the field.” Kesenne and Jeanrenaud are joined in this view by a sizeable list of others….

Of course, the presumption that club owners do not profit maximize is also found in the literature on US sporting leagues. For their book on the baseball business, Jesse Markham and Paul Teplitz (1981, p. 26) interviewed ten owners as well as various other club executives and concluded that owners “were motivated to enter the baseball industry more out of reason of personal gratification, love of the game, devotion to professional sports generally, or out of civic pride than by the prospects of profits.” Markham and Teplitz claim that owners “satisfice,” that is, they seek “good enough” performance—analogous to utility maximization subject to a minimum profit constraint or, as the English football report put it, “playing success whilst remaining solvent.”3

There is no dearth of newspaper articles or television shows where one can find pious ownership claims about their motives. Joe Maloof, owner of the National Basketball Association (NBA)’s Sacramento Kings, for instance, on 13 May 2003, appeared on Jim Rome’s ESPN show and stated: “We have one goal in mind and that’s to win a title. We’re not going to rest until we have that for the city of Sacramento and for our franchise. We’ve never had a title and that’s what we need to get.”4

Another line of economic analysis of sports leagues holds either that team owners fundamentally maximize profit or that analyzing leagues under the profit-maximization assumption provides a useful efficiency standard against which to assess actual performance.

….

Most economists do not accept at face value assertions from ownership to the effect that they are motivated strictly or mostly by civic pride or eleemosynary goals. Interviews and survey data that produce self-proclaimed, non-selfish motives can be found among executives in many industries.

Because of this distrust of the survey interview methodology, some economists have attempted to seek empirical confirmation of ownership motivation. Noll (1974) finds that ticket prices are set where the price elasticity of demand is sufficiently close to unity, so that the hypothesis of profit maximization cannot be rejected…. Of course, it is possible that teams follow profit-maximizing behaviour with regard to ticket pricing, and utility-maximizing behavior with regard to player salaries (by offering above competitive salaries). Furthermore, as Kesenne and Pauwels (2002) point out, profit and win maximizers are likely to follow identical pricing rules.7

Hunt and Lewis (1976) study the level of individual team dominance in MLB with respect to what level of dominance produces profit maximization and what level produces revenue maximization. They find that the actual level of attained dominance is consistent with profit maximization but below the level that would yield revenue maximization.

Scully’s findings (1974, 1989) that baseball teams pay players below their marginal revenue products are consistent with profit-maximizing behaviour, as is Zimbalist’s (1992a) estimate—using a modified Scully methodology—that on balance players are roughly paid their marginal revenue products.

Szymanski and Hall (2003) analyse the performance of 16 FA clubs that went public since 1995 to see if their behaviour changed along with ownership. The hypothesis is that if clubs were utility maximizers when privately held, then when they went public there would be increased pressure for them to perform on the bottom line. They, however, found no significant evidence of modified performance. This finding is consistent either with the argument that FA clubs are still utility maximizers after going public or the argument that clubs were always profit maximizers.8

While some of the empirical results in the literature have been consistent with the hypothesis of profit maximization, the results have not been conclusive. Indeed, Fort and Quirk (2002) find that without holding revenue and labour demand functions constant, it is not possible to find a definitive test to discern whether owners in a league are profit or win maximizing. Still another hypothesis was suggested by author James Michener in his book Sports in America (1976, p. 441):

In the early years of every professional sport, the owners were men of great dedication and expertise…. Their type was soon superseded, however, by the business tycoon who made his fortune in trade, then dabbled in sports ownership both as a means of advertising his product and finding community approval. The beer barons—Jacob Ruppert with his New York Yankees and Augie Busch with his St Louis Cardinals—were prototypes; they became famous across America and the sales of their beer did not suffer in the process. It is interesting that when William Wrigley, the Chicago tycoon, wanted to buy into the National League, he was strongly opposed by Colonel Ruppert, who feared such ownership might be used to commercialize chewing gum.

Then came a third echelon of ownership, the corporate manager who bought a club not only to publicize his business enterprises but also to take advantage of a curious development in federal tax laws.

One could easily quibble with aspects of Michener’s taxonomy. What are particularly interesting for our purposes, however, are the notions that: (a) ownership motives might change over time, particularly as franchise values skyrocket—it being one thing to treat a sports club as a plaything when it is purchased for $lm, yet quite another when it is purchased for $800m, and (b) within a given league, ownership motives may vary.

II. WHY DO OWNER OBJECTIVES MATTER?

The behaviour of clubs and the performance of sporting leagues may be affected by objectives of owners. If club owners are profit maximizers, then they would invest in team success up to the point where the expected marginal revenue from an additional win is equal to the marginal cost. In contrast, if owners are utility or win maximizers, then they may invest beyond this point.9 Thus, if some clubs in a league are utility maximizers and others are profit maximizers, it may provide an additional source of competitive imbalance.10 Of course, if it is the owners of small market teams that utility maximize (while the owners of large market teams profit maximize), then playing balance may be enhanced.

Rottenberg (1956) argued that a league with profit maximizing owners will be more mindful of the need to maintain a certain level of balance and, hence, will be more restrained in labour-market spending.11 In contrast, a league of individual utility maximizers will prioritize winning over league success and spend more aggressively on the players’ market, even if it renders certain teams perennially dominant.

While this logic suggests that profit-maximizing behaviour will lead to greater competitive balance, El Hodiri and Quirk (1971) show that this generally will not be the case as long as market size and revenue potential remain disparate across the teams. Underscoring this point, a recent article by Burger and Walters (2003), using data from MLB during 1995–9 and respecifying the traditional revenue equation, find that profit-maximizing teams in the largest markets will value a player six times more than teams in the smallest markets, and that, within a given market, when a team is in contention, it can raise a player’s value sixfold.

In theory, whether owners in a league are profit or utility maximizers may also affect the success of policies to promote competitive balance. If we assume that owners maximize winning and, therefore, they spend any available revenue on improving their team, then the collective selling of television or Internet rights or other revenue-sharing schemes will improve league balance (Cairns et al., 1986; Kesenne, 1996).12 This is so because collective selling will result in less money for rich teams and more money for poor teams, and, by assumption, this will yield greater equality in payroll spending across teams. Conversely, if we assume that owners maximize profits and that fan attendance depends only on the relative quality of the home team, proportional revenue sharing will not alter the relative marginal revenues from winning and, thus, will not alter the relative payrolls or talent distribution (although all salaries would be reduced under most revenue sharing schemes) (Fort and Quirk, 1995; Vrooman, 1995; Marburger, 1997).13

There is one potentially significant caveat to the last assertion. When teams sign a free agent, they do not know how the player will perform and what impact his performance will have on revenues. They can only estimate a player’s marginal revenue product. Hiring players, then, comes along with risk. Teams with higher revenues may be less risk averse and more willing to be aggressive in the free-agent market. Revenue sharing, although it may not alter the expected relative marginal revenue product of a player, may change owner behaviour by providing poorer teams with a larger financial cushion and making them less risk averse. It may also increase the risk aversion among owners of high-revenue teams. Insofar as revenue sharing promotes either of these results, it may promote competitive balance.14

Although owners’ objectives will affect behavior and league success, existing literature does little more than suggest possible tendencies. Most observed behaviour is consistent with a variety of objective functions. In his 1971 piece on English football, Sloane observes that an owner’s objective could be “rationalised so that it is consistent with almost any type of behaviour and therefore tends to lack operational significance.” And Cairns et al. (1986, p. 10) conclude that “there are great difficulties involved in distinguishing between the competing hypotheses.”15

To be sure, owners themselves seem to have difficulty distinguishing between different objectives. Listen, for instance, to Robert Kraft, owner of the National Football League (NFL)’s New England Patriots: “And if you’re passionate about winning and you help put an organization in place that can win, the business part will follow.” And listen to Robert Johnson, founder of the BET network and [then] owner of the expansion NBA Charlotte Bobcats: “I’m first and foremost a business guy and I don’t see a distinction between a winning team and a profitable team.” Or to Mark Cuban, owner of the NBA’s Dallas Mavericks, expressing a somewhat more enlightened view:

There’s a misconception that people look at sports and say the real people who focus on the business side are just the ones that reduce costs, that the only way to really reflect running it as a business is to keep your player costs low when the reality is if I increase my sales enough it doesn’t matter what my costs are.16

The likelihood is that owner-objective functions are both more nuanced and more varied than is allowed in the literature attempting to model sports leagues. In the next section, I suggest a more complex view of what today’s club owners seek to maximize.

III. WHAT DO OWNERS REALLY SEEK?

Owners, in fact, take their returns on sports franchises in a number of ways. As indicated above, one obvious aspect of their return is the fun, perquisites, power, and ego gratification they receive. Ownership, in part, is a consumption good. Thus, it would make sense to think of owners as maximizing their total (consumption and investment) return, not just their financial profit.

A significant part of the investment return is indirect. For instance, team ownership provides opportunities to develop new business relationships and to leverage political influence—potentially benefiting the owner’s other investments as well as the sports team….

With few exceptions, franchise ownership also produces substantial capital gains. According to Fort’s estimates (2002, p. 389), during the 1990s the average annual rates of franchise appreciation were 11.3 per cent in MLB, 17.7 per cent in the NBA, 10.7 per cent in the National Hockey League (NHL), and 12.7 per cent in the NFL. Moag (2002, p. 2), using a different methodology and updating through mid-2002, estimated the annual rate of return to owning a baseball franchise to be 12.44 per cent from 1960 to 2002, which would put it well above the return to common stock ownership for the same period (6.91 per cent for the S&P 500 through 30 June 2002).18 According to Szymanski and Kuypers (1999, p. 19), an investor who paid 385 pence for a share of Manchester United stock in 1991 and sold the share in mid-1998 would have experienced a capital gain of £24.40 on the single share for an annual rate of return of above 30 per cent.

In each of these instances—consumption value, business connections, political ties, tax benefits, and capital gains—the investment return will not show up on the income statement and is long term in nature. Other than the tax shelter, each of these returns is enriched by having a winning team. This suggests that owners’ objective functions may contain both wins and profits. It may also include accumulation of star players.

There is also a great many ways for an owner to take short-run and pecuniary returns.19 First, an owner can boost other companies in his or her portfolio through favoured contracting with the team. Many team owners today own entities (such as TV, cable, or radio stations, and facility management, concessions, or chartering companies) that do business with the team. When the owner does business with himself he can charge whatever prices he likes—it is money in one pocket or the other. This practice, known as a related-party transaction or transfer pricing, can reduce reported franchise revenues substantially. Consider the example of MLB’s Chicago Cubs.

According to 2001 figures that MLB Commissioner Bud Selig delivered to the U.S. Congress, the Chicago White Sox’s income from local TV, radio, and cable was $30.1m, and that of the Chicago Cubs was $23.6m. Yet, everyone knows that the Cubs are by far the more popular team in the Windy City, and TV ratings bear this out: in 2001 the Cubs’ average ratings were 6.8 on over-the-air broadcasting and 3.8 on cable; the White Sox’s were 3.6 and 1.9, respectively. And this does not take account of the fact that the Cubs games are shown on super-station WGN which reaches 55m-plus homes nationally.

So, how can we understand Selig’s figures? The Cubs are owned by the Tribune Corporation, which also owns WGN. [Ed. Note: The team and its related properties were sold to Tom Ricketts in 2009 for $845 million.] The Tribune Corporation, in effect, is transferring revenue away from the Cubs and lowering the costs of WGN. It does this by using related party transactions, which are entirely lawful and widely used in the sports industry and across business generally. According to Broadcasting & Cable, the industry’s authoritative source, the estimated value of the Cubs’ local media earnings in 2001 was $59m. If the Cubs reported this figure instead of $23.6m, then their reported $1.8m loss would become a $33.6m profit in 2001!20

Why would the Cubs (and all other baseball teams) want to reduce their reported revenues? There are several possible reasons. First, since 1996, MLB has had a revenue-sharing system that levies a tax on a team’s net local revenues. In 2001 this tax was at 20 per cent (in 2003 the effective marginal tax rate is close to 40 per cent) (Zimbalist, 2003, ch. 5). Thus, for every dollar in local revenue not reported in 2001, the team saved just under 20 cents.21 Since WGN pays no such tax to the broadcasting industry, it is preferable for the parent corporation, Tribune, to have the profits appear on WGN’s books.

Second, baseball teams (and even the Cubs, who were seeking public permission to erect higher leftfield stands in 2002) seek various kinds of public support for their facilities. They may believe that the more impecunious they appear, the more likely it is that such support will be forthcoming.

Third, every few years the owners negotiate with the players over a new collective-bargaining contract. The owners always seek new restrictions in the labour market to lower salaries. One of the justifications for these restrictions commonly is that the teams are losing money. Whether or not the Players Association is persuaded by such arguments, it appears to be permanently fixed as part of the owners’ opening gambit.

Fourth, MLB is the only professional sport in the United States that has a presumed antitrust exemption. Periodically, MLB is called before Congress to justify this special treatment. One of the arguments that MLB has repeatedly trotted out—most recently by Selig before the U.S. Congress in December 2001—is that the industry cannot possibly be abusing its market power because it is not profitable.

Fifth, ownership may believe that claims of poverty may help to justify higher ticket or concessions prices to the fans.

As in the example of the Chicago Cubs, many MLB teams and teams in other sports make extensive use of related party transactions. In each case, the team’s true financial return is unlikely to be found on the bottom line. Hence, a cursory glance at a team’s income statement is unlikely to reveal ownership motives.

More generally, it is common for owners to treat sports teams as part of their entire investment portfolio. Often, the team itself is not managed as a profit centre, but rather as a vehicle for promoting the owner’s other investments. Owners can take their investment returns in a number of ways. For instance, George Steinbrenner used his New York Yankees to create the YES regional sports network in the nation’s largest media market. In 2001, YES had a market value upward of $850m. Rupert Murdoch admitted that his purchase of the Dodgers paid off because it enabled him to prevent Disney from creating a regional sports network in southern California. In 1998, Disney had signed up its MLB Angels and NHL Mighty Ducks to a 10-year cable contract with Fox Sports Net West II for a seemingly well-under-market $12m a year. It is not unlikely that Disney received other benefits from the News Corp. (such as carriage at an attractive price for Disney’s many cable channels on the News Corp.’s worldwide satellite distribution systems).

Tom Hicks hopes to use his ownership of the Texas Rangers to develop some 270 acres of commercial and residential real estate around the ballpark in Arlington and to grow his Southwest Sports Group, among other things. [Ed. Note: These efforts proved unsuccessful, and Hicks sold the Rangers in 2010.] Dick Jacobs exploited his ownership of the Indians to promote the value of his downtown real estate. And so on. Once again, the team’s income statement will not tell the whole story.

One important implication of the preceding discussion is that competitive balance may be more elusive to sporting leagues. Not only may different owner objective functions and team-specific revenue potentials engender imbalance, but team synergies with related business interests may exacerbate inequalities. For instance, when Tom Hicks signed Alex Rodriguez to a 10-year deal for $25.2m annually, he was thinking about the return A-Rod would bring to all of his businesses, not just to the Rangers. Thus, what might appear as utility-maximizing behavior by an owner is really global (portfolio-wide) profit-maximizing behavior. Put differently, owners may find that the best way to profit maximize globally is to win maximize at the team level.24

When owner investment in players yields returns to both the ball club and to other businesses of the owner, this may be a significant additional source of league imbalance. Under such circumstances, leagues may be justified in imposing constraints on the legal form of ownership, such as proscribing corporate ownership.

In the United States, however, other than the general and welfare-diminishing prohibition on municipal ownership in all leagues, the NFL is the only league to limit systematically the ownership form. It does so by outlawing corporate ownership. There is an irony here, because the NFL, with its relatively hard salary cap and extensive revenue sharing, is probably the only U.S. league that does not have to worry about competitive balance.

….

In sum, one obvious conclusion to draw from the foregoing discussion is that owners maximize global, long-term returns and that these are very different from a team’s reported annual operating profits. While, at today’s stratospheric franchise prices, it is problematic for most owners to be pure sportsmen—maximizing utility without a financial constraint—it is almost a certainty that different owners give different weights to the variety of arguments in their objective functions. The next task for modelling the behaviour and performance of sports leagues is to take fuller account of this probable diversity of ownership objectives within a given league.

References

Brower, J. (1977), ‘Professional Sports Team ownership: Fun, Profit and Ideology of the Power Elite’, Journal of Sport and Social Issues, 1(1), 16–51.

Burger, J., and Walters, S. (2003), ‘Market Size, Pay, and Performance: A General Model and Application to Major League Baseball’, Journal of Sports Economics, 4(2), 108–25.

Cairns, J., Jennett, N., and Sloane, P. J. (1986), ‘The Economics of Professional Team Sport: A Survey of Theory and Evidence’, Journal of Economic Studies, 13, 3–80.

Dabscheck, B. (1975a), ‘Sporting Equality: Labour Market versus Product Market Control’, Journal of Industrial Relations, 17(2), 174–90.

——— (1975b), ‘The Wage Determination Process for Sportsmen’, Economic Record, 51(133), 52–65.

Daly, G., and Moore, W. (1981), ‘Externalities, Property Rights and the Allocation of Resources in Major League Baseball’, Economic Inquiry, 19(1), 77–95.

Davenport, D. S. (1969), ‘Collusive Competition in Major League Baseball: Its Theory and Institutional Development’, American Economist, 13, 630.

Demmert, H. G. (1973), The Economics of Professional Team Sports, Lexington, MA, D. C. Heath.

El Hodiri, M., and Quirk, J. (1971), ‘An Economic Model of a Professional Sports League’, Journal of Political Economy, 79(6), 1302–19.

Ferguson, D. G., Stewart, K., Jones, J. C. H., and LeDressay, A. (1991), ‘The Pricing of Sports Events: Do Teams Maximize Profit?’, The Journal of Industrial Economics, 34(3), 297–310.

Fort, R. (2002), Sports Economics, Upper Saddle River, NJ, Prentice Hall.

——— and Quirk, J. (1995), ‘Cross Subsidization, Incentives and Outcomes in Professional Team Sports Leagues’, Journal of Economic Literature, 33(3), 1265–99.

——— (2002), ‘Owner Objectives and Competitive Balance’, Washington State University, unpublished manuscript.

Hunt, J. W., and Lewis, K. A. (1976), ‘Dominance, Recontracting and the Reserve Clause: Major League Baseball’, American Economic Review, 66(5), 936–43.

Jones, J. C. H. (1969), ‘The Economics of the National Hockey League’, Canadian Journal of Economics, 2(1), 1–20.

Kesenne, S. (1996), ‘League Management in Professional Team Sports with Win Maximizing Clubs’, European Journal for Sports Management, 2, 14–22.

——— (2000), ‘Revenue Sharing and Competitive Balance in Professional Team Sports’, Journal of Sports Economics, 1(1), 56–65.

——— and Jeanrenaud, C. (1999), ‘Introduction’, in S. Kesenne and C. Jeanrenaud (eds), Competition Policy in Professional Sports, Antwerp, Standard Editions.

——— and Pauwels, W. (2002), ‘Club Objectives and Ticket Pricing in Professional Team Sports’, Department of Economics, University of Antwerp, unpublished manuscript.

Koppett, L. (1973), ‘A Strange Business, Baseball’, The New York Times Magazine, 2 September.

Lewis, M. (2003), Moneyball: The Art of Winning an Unfair Game, New York, Norton.

Marburger, D. (1997), ‘Gate Revenue Sharing and Luxury Taxes in Professional Sports’, Contemporary Economic Policy, 15,114–23.

Markham, J., and Teplitz, P. (1981), Baseball Economics and Public Policy, Lexington, MA, D. C. Heath.

Michener, J. (1976), Sports in America, New York, Random House.

Moag, J. (2002), Moag & Company Industry Analysis, Spring.

Neale, W. (1964), ‘The Peculiar Economics of Professional Sports’, Quarterly Journal of Economics, 78, 1–14.

Noll, R. G. (1974), ‘Attendance and Price Setting’, in R. G. Noll (ed.), Government and the Sport Business, Washington, DC, Brookings.

Rascher, D. (1997), ‘A Model of a Professional Sports League’, in W. Hendricks (ed.), Advances in the Economics of Sport, Vol. 2, Greenwich, CT, JAI Press, 27–76.

Rottenberg, S. (1956), ‘The Baseball Players’ Market’, Journal of Political Economy, 64, 242–58.

Schofield, J. A. (1982), ‘The Development of First-class Cricket in England: An Economic Analysis’, Journal of Industrial Economics, 30(4), 337–60.

Scully, G. (1974), ‘Pay and Performance in Major League Baseball’, American Economic Review, 64(6), 915–30.

——— (1989), The Business of Professional Baseball, Chicago, IL, University of Chicago Press.

——— (1995), The Market Structure of Sports, Chicago, IL, University of Chicago Press.

Sloane, P. J. (1971), ‘The Economics of Professional Football: The Football Club as a Utility Maximiser’, Scottish Journal of Political Economy, 17(2), 121–46.

Szymanski, S., and Hall, S. (2003), ‘Making Money Out of Football’, The Business School, Imperial College, London, unpublished manuscript.

——— and Kuypers, T. (1999), Winners and Losers: The Business Strategy of Football, London, Viking Books.

Vrooman, J. (1995), ‘A General Theory of Professional Sports Leagues’, Southern Economic Journal, 61, 971–90.

Zimbalist, A. (1992a), ‘Pay and Performance in Major League Baseball: Beyond the Scully Model’, in P. Sommers (ed.), Diamonds Are Forever, Washington, DC, Brookings Institution Press.

——— (1992b), Baseball and Billions, New York, Basic Books.

——— (2003), May the Best Team Win: Baseball Economics and Public Policy, Washington, DC, Brookings Institution Press.

Notes

….

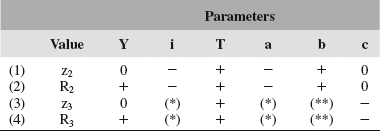

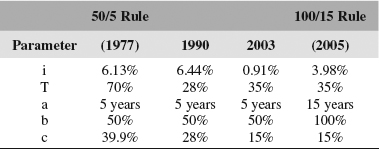

2. In their excellent overview of English soccer, Stefan Szymanski and Tim Kuypers (1999, p. 16) write that the FA first imposed dividend limitations in 1896. The first limit was 5 per cent of paid-in capital. It was raised to 7.5 per cent in 1920 and to 15 per cent in 1983, but most teams had ceased to pay dividends in the 1950s.

3. The most common formalization of this approach is to assume win maximization subject to a break-even constraint.

4. Quoted in the Sports Business Daily, 14 May 2003, p. 20.

….

7. This result may be altered if home-field advantage is partially based on attendance.

8. Szymanski and Kuypers (1999, p. 19) point out that when Manchester United went public in 1991, it organized a holding company that received most of the team’s revenue. Among other things, the holding company was a way to avoid FA regulations over the appointment of directors and limitations on dividend pay-outs.