ONE

Building the Framework for Mentoring across Differences

When Mia and Christopher met for the first time, they were immediately struck by the ways in which they were not alike: gender, age, self-expression, and power differential within the organization. You will likely observe substantial differences between you and your mentoring partner. Some things (like ethnicity, race, and gender) may be easy to see; and some things (like values, motivation, and background) are not so visible. Often, we make unconscious assumptions about the meaning of what we see, and those assumptions may be incorrect because ethnicity, race, and gender are not always obvious and don’t always follow an archetype. Nonetheless, each element of identity, and the assumptions that we make about them, affect how we view the world and how we view our mentoring partner.

When mentoring partners focus too much on differences, or when they can’t relate across the differences, the result is fragmentation and judgment. Although it is tempting, and perhaps more comfortable, to focus on what we have in common with someone else, this can discourage authenticity, exclude the things you may learn if you pay attention to differences, and lead to other problems. The first question most people ask themselves when seeking to connect with a new person is, “What do we have in common?” In general, people connect based on commonality, which can give ground to build relationships. But when we are so focused on commonality, differences are ignored or even judged. Unconsciously, we create groupthink; and those who do not share the group’s commonalities feel devalued, excluded, and discouraged from sharing differing ideas and opinions. Often, those of us who are excluding, however inadvertently, have no idea this is happening.

A multiplicity of factors make up our identity, shape the way we look at things, and impact our actions and our behavior. In mentoring (and in life in general), the idea is not to accentuate, avoid, or judge the ways we are different from one another but to honor those differences by balancing commonalities and differences. When we understand and appreciate the differences between us, we can leverage them to improve our conversations, deepen our learning, and spur creative thinking. When we see our partners through the lens of cultural competency, we enhance the relationship between mentor and mentee and boost mentoring outcomes.

What Is Mentoring?

We define mentoring as “a reciprocal learning relationship in which a mentor and mentee agree to a partnership where they work collaboratively toward achievement of mutually defined goals that will develop a mentee’s skills, abilities, knowledge and/or thinking.” This description is packed with a good deal of meaning for our work here. We focus on four key concepts that relate most closely to bridging difference in a mentoring relationship: reciprocal, learning, relationship, and partnership.

Mentoring Is Reciprocal

One of the most beneficial aspects of mentoring is its inherent reciprocity. When reciprocity is present, both mentor and mentee fully engage in the relationship. If the relationship is truly working, there is a big payoff for both parties. Perspectives expand, and each person gains new insight into where their mentoring partner is coming from. Each has specific responsibilities, contributes to the relationship, and learns from the other. Reciprocity is essential to effective mentoring, and the degree to which mentors mutually benefit from it is often surprising to both mentoring partners.

Mentoring Involves Learning

Mentoring, at its very core, is a learning relationship: learning is the purpose, the process, and the product of a mentoring relationship.3 Mentees must come to the relationship as learners, and mentors must view themselves as learning facilitators and as learners. When both partners have a learning mindset, there is no failure. Rather, each encounter with difference and misunderstanding is an opportunity to learn from one another, to course correct and build on our new understandings. When mentors are open to learning, they often learn as much as (if not more than) their mentees.

Mentoring Requires a Strong Relationship

Effective mentoring requires a strong relationship between mentoring partners. From the very start, mentor and mentee must begin to build a relationship that is open and trusting and to honor each other’s uniqueness. This doesn’t happen overnight. Give your relationship time to develop and grow. It is the mentor’s responsibility to create a safe and trusting space that enables a mentee to stretch and step outside their comfort zone, take risks, and show up authentically. It is the mentee’s responsibility to be willing to take these risks, engage with their mentor, and ask for what they need. Both partners need to work at establishing, maintaining, and strengthening the relationship through time.

Mentoring Is a Partnership

Even though the mentor may be higher on the org chart than the mentee, a mentoring relationship is a partnership. Mentoring partners need to establish agreements that are anchored in a bedrock of trust. Trust is predicated on respecting your mentoring partner for who they are and understanding their needs. You are going to need to continuously work at building and strengthening your relationship and holding each other accountable for results. That is what strong partnerships do, and they do it well.

Mentoring is always a collaborative endeavor. Mentor and mentee work together to establish a successful relationship, achieve the mentee’s goals, and make mentoring a win-win for both partners. Together they build the relationship, share knowledge, and come to consensus about the focus of the mentee’s desired learning, and they actively engage with one another to achieve it.4

The Mentoring Cycle

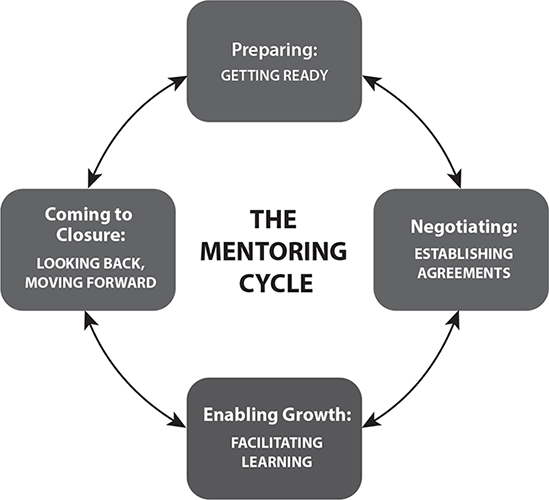

Mentoring relationships travel through a predictable four-phase cycle, each building on the one before it to create a fluid developmental sequence: preparing, negotiating, enabling growth, and coming to closure. Being able to anticipate each phase, knowing where you are in the process, and understanding what each phase offers in terms of learning and growing with your mentoring partner, makes your work together more productive and builds a strong foundation for your partnership to succeed. This mentoring framework, which Lois presented in The Mentor’s Guide, combines good mentoring practice with what we know about how adults learn best.5

FIGURE 1.1 The Mentoring Cycle

Figure 1.1 shows the four phases of the mentoring cycle. We refer to these phases throughout this book. There is no set time for getting through this cycle; the length of each phase varies depending on the mentoring relationship. The two-way arrows between each phase indicate that the phases are fluid: mentoring partners sometimes need to revisit an earlier phase in the cycle in order to move forward. In this chapter we follow Christopher and Mia’s journey as they begin phase 1 of their mentoring partnership.6

In the hundreds of conversations we’ve held with mentors and mentees, we’ve found that successful partnerships—those that can point to significant learning or progress—take care to follow these phases, often revisiting steps as needs and goals change.7 Positive movement through each phase rests on successful completion of specific behaviors and processes. Have faith in the process and be patient.

Phase 1. Preparing

Preparing has two parts: preparing yourself as mentor or mentee and then preparing the relationship. Preparing yourself is critical, yet it is frequently overlooked. Most folks just step into mentoring and gear up when they first meet their mentoring partner. Maybe they look over their partner’s CV and get some background info about the person. But just as you might get your thoughts together before making a presentation, the better way to mentor is to prepare yourself before you engage in your mentoring relationship.

The second part of preparing—preparing the relationship—focuses on the kickoff conversation you engage in with your mentoring partner. Mia and Christopher, whom you met earlier, are just embarking on their mentoring relationship. They haven’t scratched the surface of it yet, let alone begun to bridge differences. What you read in the mentoring story before this chapter represents everything Mia and Christopher know about each other, and it’s the tip of the iceberg—gender, level of professional experience, job title, and age. What they do not yet know still lies beneath the surface: their unique motivations and expectations. They have work to do to get to know each other beyond what they see at first glance, and this work will lay the foundation for a trusting relationship that encourages authenticity.

Both Christopher and Mia need to explore and discover the other person as an individual. What do they care about? What motivates them? What is their view of work and authority? What has their personal journey been? The purpose of this phase is to work toward creating a fuller understanding about who your mentoring partner is: What makes up the “who” of this unique individual? Getting to know another person and reaching a deeper level of understanding doesn’t happen in one meeting. It is a process that unfolds gradually and relies on a high degree of trust that takes time to build. With trust comes increased comfort. The more comfortable one is, the more open one can be; the more open one can be, the more authentic the conversation. The more authentic mentors and mentees are with each other, the deeper and more effective the learning.

Mia and Christopher’s first meeting was typical of many relationships. Although both partners felt like they knew what they needed to accomplish, and felt prepared to succeed, neither had prepared themselves in a way that would build trust and understanding.

Mia was excited and impatient to get started—she felt more than ready for her meeting. She arrived in Christopher’s office with three lists: the goals she was ready to work on, the matters she had worked on since she joined F3, and the partners who had a book of business she admired. After a few minutes of getting acquainted, Mia handed her lists to Christopher. “This is what I want to work on,” she said. “What’s my next best step?”

Christopher was taken aback. He was impressed with Mia’s organization and drive, but to him, she appeared to be moving way too fast. “Seems a bit soon to dive into that,” he said, handing back her lists after a brief glance. “I need to understand more about you and how you work best.” Christopher smiled at Mia, but he felt like a tornado had just burst through his door.

Disappointed and annoyed, Mia took back her papers. She was too busy for this. Making time for mentoring meetings was actually taking up time she could be spending on work, and she just wanted to get moving. How long could this take, anyway? And why didn’t Christopher take her at her word that she knew what she wanted to work on? He seemed too dismissive of the goals and the lists she had spent so much time crafting. She wondered if she should just cut her losses and find another mentor.

As your mentoring partnership unfolds, trust is built and your relationship grows. The information you need about one another reveals itself over time.

Phase 2. Negotiating

Negotiating is the “business” phase of the relationship. Taking time to set processes and structures in place that you both agree on helps ensure mentoring success. Negotiating the parameters of your mentoring relationship involves conversations about goals, processes, ground rules, timelines, and accountabilities. When well executed, negotiating builds a rock-solid foundation for moving forward and staying on track, but it cannot be accomplished without first understanding who your mentoring partner is. Otherwise, mentoring becomes formulaic; better mentoring is not one-size-fits-all.

At their next meeting, Mia walked into Christopher’s office with a pen and a notebook—no lists this time. She felt a real urgency to get to work on her list of goals. Though she was still annoyed about their last meeting, she was also pragmatic. This was a great opportunity for her to connect with an influential colleague who probably did have something to teach her. She didn’t want to alienate Christopher, so she decided to try his approach.

Christopher was ready for another onslaught when Mia walked in, but he was delighted to see Mia’s notebook and no lists. She seemed ready to listen. So, after some small talk, he began. “Let’s set some ground rules,” he said.

Mia sighed to herself. She was ready to work! Why did he want to drag this on? “I’d better buckle up,” she thought, “this is going to be a long ride.”

Phase 3. Enabling Growth

Phase 3, enabling growth, is the longest phase of the mentoring relationship. Now the work of mentoring begins in earnest, as you and your mentoring partner dive into goal achievement. This is where you will spend most of your time, so you want to do a good job of preparing the relationship to keep it growing, keep the learning fresh, and move forward toward achieving your mutual goals.

Mentoring relationships often stall out during this phase, so mutual accountability is paramount. Frequent check-ins will allow for course correction on the process, the goal, and the relationship. During this phase the mentor is supporting, challenging, and encouraging the mentee to create and articulate a vision of possibility. The mentee needs to be able to ask for what they need, and feedback conversations are the norm.

After a few more meetings, Christopher and Mia settled on two goals for Mia. The first one was straightforward: by the end of the mentoring year, she would identify ten potential clients or referral sources and build relationships with the key players. The second goal, however, was a bit tougher. Because Mia was so focused on becoming a partner, she would need to become more aware of how she presented herself so that others saw her potential.

From the start, Christopher knew that Mia needed to learn to speak more slowly and moderately. But telling her to slow down and encouraging her to realize that her speedy approach was holding her back was another matter altogether. Mia’s energy was a positive attribute, her verbal attack mode less so. Christopher wanted Mia to show up authentically, and he anticipated that this would be a sensitive subject. Experience had taught him that telling Mia to slow down was only going to put her on the defensive, so he decided to put the ball in her court.

Christopher asked Mia questions about how she thought she was viewed in the firm. She seemed puzzled by the query. “I’ve never thought about it,” Mia said. “I’m really not sure . . . is this important?”

“Well,” Christopher replied slowly, “I’ve learned that when I know how clients and colleagues see me, it helps me know how to approach them and better get my points across.” Therefore, the second goal they set was more long-term and personal: over the next six months, Mia would work on increasing her self-awareness so that she understood how she was perceived by her fellow attorneys and potential clients.

Mia was taken aback—six months of wasting time on “getting to know herself”? This wasn’t therapy! But on reflection, and despite her initial suspicions, she thought that it might be an interesting learning experience. Still, she found herself annoyed and confused by her mentor’s motives. Did Christopher really respect her? What was she doing that even made him say that? She wondered if it was a male-female thing. Maybe a woman partner would have been better after all, Mia mused.

Phase 4. Coming to Closure

In the fourth phase, mentor and mentee focus on consolidating and integrating the learning, evaluating the learning, celebrating the learning, and moving on. This short phase actually offers the most opportunity for growth and reflection, regardless of whether the relationship has been positive or not. Good closure conversation acts as a rite of passage, offering a framework for moving on and opening the door to new development opportunities. Closure provides an opportunity to reflect on what you’ve learned, process it, and talk about how you are going to leverage and take your learning to the next level.

Phase 4 is not a one-time-only offer. Mia and Christopher will circle back through this phase several times if they continue to be mentor and mentee for the long haul. Successful closure creates new opportunities for growth. If closure is to be a mutually satisfying learning experience, both partners must be prepared for it. A closure conversation is one of the most significant development conversations you will ever have as a mentor or mentee, so take every opportunity to maximize the experience. (As you’ll learn later in this book, closure doesn’t necessarily mean “the end.” It’s a good rule of thumb never to bring a mentoring relationship to closure without identifying the next growth goal.)

» YOUR TURN «

1. Think about your mentoring experiences. In what ways were any of the four concepts (partnership, strong relationship, learning, reciprocity) present? In what ways were they missing?

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

2. Reflect on your past mentoring experiences. Might a more structured model have helped make them more successful? In what ways?

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

The mentoring concepts laid out in this chapter are basic to the mentoring process. In the next chapter you’ll begin to build the foundation for allowing cultural competency to inform your mentoring partnerships.

Chapter Recap

1. The ideal mentoring relationship is a cycle comprised of four phases: preparing, negotiating, enabling growth, and coming to closure. Completion of each phase is critical to a successful mentoring relationship.

2. Mentoring pairs can move backward and forward between the phases, but skipping a phase will deprive each partner of the full benefit of mentoring.

3. Mentoring is a collaborative, reciprocal partnership that focuses on mutually defined goals for the mentee’s learning and development. It is cocreated by the mentor and mentee and customized based on each pair’s needs and preferences.

4. Mentoring partners can connect based on what they have in common and based upon their differences. Pairs need not view differences as obstacles to connection. The key is to understand differences and use them as ways to connect with one another.