FIVE

Preparing the Relationship

Making the most of your mentoring relationship requires learning from differences. Once you’ve prepared yourself by expanding your understanding of your own culture, identity, and biases, you need to get a good sense of who your mentoring partner really is and the differences between you. As the sociologist Milton Bennett has noted, behavior and values must be understood both in terms of the uniqueness of each person and in terms of the culture of that person.35 There is a bonus! By getting to know your mentoring partner in a deeper way, you may find that you get to know yourself even better. Likely, you will discover that awareness of difference begets more awareness and mutual understanding, which deepens as you explore your differences.

Once Aesha and Heather were settled in with their coffee, Heather launched in. She introduced herself briefly, shared her history at the company, and then described some of the pressures she thought Aesha would face as a young professional with newly acquired health-care experience.

As Aesha listened, one question after another popped up in her head. As Heather kept talking, more questions piled up, and Aesha waited for a break in the story to ask them. Heather, however, continued, offering detailed examples of challenges she had faced in navigating the system, becoming a team member, building successful teams, and hinting at some of the departmental politics that Aesha might face. After ninety minutes, Heather announced that they’d run out of time for the day.

Aesha left Starbucks with her notebook filled with notes and her mind bursting with questions as she tried to process all that she had heard.

Heather didn’t know any more about Aesha after their meeting than she did before it. And although Aesha now knew a lot more about Heather, she was curious to learn more and had many unasked questions. This meeting was all about Heather—Aesha, while physically present, was effectively absent. What was going on here? Heather was delighted to be a mentor and eager to share her experience. She knew how difficult it could be to gain a foothold at Any Healthcare, and she’d learned a lot of hard lessons on her way up. Now she wanted to pay it forward by easing Aesha’s journey.

Aesha listened, as she felt befitted her role as mentee. Although she had many questions, she didn’t want to interrupt Heather or appear disrespectful. Aesha was grateful that Heather had agreed to mentor her but wondered if she would ever be able to really relate. A lot was happening under the surface, but the point here is what wasn’t going on: a genuine conversation. We’ve eavesdropped on what Aesha sat through for an hour and a half and seen that without establishing a real connection, mentoring partners can simply go through the motions and never truly engage with each other or with the mentoring process.

Mentoring cannot reach its full potential if you jump right in and don’t take time to prepare your relationship adequately. Relationships take work and time to mature. When both parties take the time for self-reflection and to understand each other in a way that goes below the surface, they begin to grow and flourish with good conversation.

The Process: Good Conversation

Good conversation is essential in building and maintaining an effective mentoring relationship. Before we dive more deeply into the process, let’s begin with your own experiences.

» YOUR TURN «

Think about a time when you had a really good conversation. What happened that made it a good conversation? What did you and your conversation partner do (the behaviors) and what was going on (the conditions) that made it a good conversation? Make a list of descriptors. (This list can be helpful as a checklist to ensure you stay in good conversation.)

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

The Five Levels of Conversation

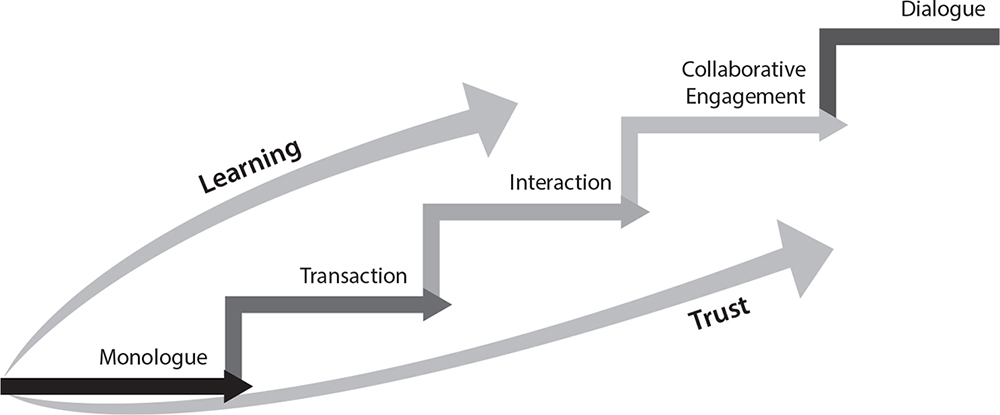

Mentoring conversations are built on a foundation of trust. Learning increases as the conversation moves from basic information transaction to a genuine collaboration and dialogue. Our levels of conversation model (Figure 5.1) illustrates the five levels of conversation and their relationship to building trust and promoting learning in a mentoring relationship.36

1. Monologue: The levels begin with monologue, where one person grabs most of the airspace and ends up doing all the talking. Sometimes mentors in particular get trapped in monologue. Out of nerves, a desire to teach, or a lack of awareness, they launch into their stories and become the “sage on the stage,” attempting to impart knowledge rather than create dialogue. This is what happened with Aesha and Heather in their first meeting. Heather relayed her own journey and lessons to Aesha without allowing any time for Aesha to respond or ask questions.

2. Transaction: In the next level, transaction, an exchange of questions and answers occurs in which talk remains on the surface. Most conversations are merely transactions. A transactional mentoring conversation can feel like a checklist or a recitation of a set of to-dos. It might sound like this:

MENTOR: “Did you read the article I sent you?”

MENTEE: “Yes, I did, thanks.”

MENTOR: “Have you had you had an opportunity to talk with my sponsor?”

MENTEE: “I am happy to report it happened last week.”

FIGURE 5.1 Levels of Conversation Model

Source: © 2019, Center for Mentoring Excellence. The figure was developed by the Center for Mentoring Excellence and is described in Zachary and Fischler, Starting Strong, 166.

The back-and-forth exchange might seem like an efficient way to report progress or hold a mentee accountable for the progress, but the exchange is inherently limiting. It doesn’t generate much energy and satisfaction and does not result in real learning for either party.

3. Interaction: The third level, interaction, gets closer to good conversation, but it is not quite there yet. It often focuses on “how to” and “where to” rather than “why.” Interactions promote knowledge transfer but limit opportunities for insights, reflection, or discovery. For example, a mentee shares her current work struggle, and her mentor tries to make her feel better by stating, “I’ve felt that way myself many times. I wouldn’t worry about it.” The mentee might learn more if her mentor were instead to have asked her why she thinks the problem is occurring, or what’s going on that makes her think there is a problem. The mentor may learn more from that answer as well. Often, conversations where mentoring partners get to know each other fall into this category. Mentoring partners exchange personal information and career stories. Certainly this is both a useful and important conversation, where comfort and trust begin to build. However, for mentoring to be effective, conversations must eventually move beyond interaction.

4. Collaborative engagement: The fourth level, collaborative engagement, is where deeper insight and reflection take place. Once trust has been established, mentoring partners are willing to be vulnerable. As trust deepens, the relationship becomes stronger. The mentor learns something new about the mentee, and the mentee begins to understand that the mentor is a person who also struggled and learned along her own career path.

Aesha and Heather, for example, are still in monologue. It will likely take them a while to move through transaction and on to collaborative engagement, but it is important that they do. In the collaborative engagement stage, curiosity can move mentoring pairs forward in a significant way because there is a mutuality of need-to-know that propels conversation and compels mentoring partners to learn more and be more open to understanding differing perspectives. With increased collaborative engagement, learning can accelerate and take the partnership to a whole new level.

5. Dialogue: Dialogue, the fifth level of conversation, leads to transformational thinking that generates shared understanding from the mutual learning that is taking place. Once trust is high, there can be an open exchange of ideas without defensiveness. Sudden insights grow into new understandings. On this level, there is no debate, and no attempt to convince or change the other person’s mind about something. Both parties expand their understanding as they learn, explore, and grow. There is excitement about their learning and that expands in tandem with the new understandings they create.

Building Trust: Creating Conversations that Dig Deeper

As the days wore on, Heather’s stories and experiences sparked even more questions for Aesha. Although she admired Heather and hoped to be as successful, she seriously wondered if Heather had a life outside of work. Aesha sure hoped so, because she was not interested in a career that left no time for home and family. She had been expecting to get some guidance from her mentor on how to balance home and work life. She had thought that Heather might have some insight about this because she had been a single mom when she started at Any Healthcare, but it hadn’t come up. Aesha made herself a reminder to talk with Heather about it later but then decided instead to text Heather and ask her about it. Here’s how that exchange went:

Aesha: “Good meeting! You have a ton to offer. After we cover all the things you want to cover, I’d like to get your views on work-life balance on the agenda. Can we talk about that next time?”

When Heather received Aesha’s text, her initial response was to chuckle. She’d given up the hope of achieving any sort of balance long ago. She’d realized early on in her career that if she wanted to be successful it had to be career first. The only way she had known to provide for her son, Matthew, was to have a well-paying career so he could have some stability. Thankfully, Heather’s mother and some great care providers had been there to help with her son. Achievement at work had never been a question for Heather: she had always felt compelled to say yes to all opportunities and to be the hardest working executive. The rest would work itself out. She took a breath and texted Aesha.

Heather: “I enjoyed our meeting too. Is there really such a thing as work-life balance??? “

Aesha was confused. She felt dismissed. Was Heather signaling that she was not interested in talking about how Aesha could manage her work obligations and still have time for family? Aesha concluded that it was best not to bring up these concerns about work-life balance again and omitted the topic from the agenda she was preparing for their next meeting. Instead, she decided to find out what Heather’s expectations were for the mentoring relationship and added that to the agenda.

From the beginning, Heather assumed that Aesha was like her and wanted to get ahead, and that therefore Aesha wanted and needed the same things that Heather did when she started at Any Healthcare. Heather assumed that because Aesha was a woman, their wants, needs, and career paths would be similar. When those assumptions turned out to be erroneous, Heather simply made new assumptions. For example, when Aesha persisted in wanting to talk about family, Heather immediately assumed that Aesha wasn’t as serious about her professional success as she was.

Heather began to notice her own irritation every time Aesha brought up feeling guilty or torn between family and work, thinking, “Aesha just doesn’t have what it takes to succeed.” When Heather realized that she was making that conclusion, she felt guilty and a bit conflicted. On the one hand, Heather was proud of her own commitment to work and firmly believed that success in the industry required a 100 percent commitment. On the other hand, as she had gotten to know Aesha, she knew that her mentee had the smarts to succeed, and she’d begun learning about how real the pull of home life was for Aesha. Heather was growing concerned that her own inability to relate was preventing her from mentoring Aesha effectively.

All at once, Heather became acutely aware of her own bias for compartmentalizing work from home life and that she was making judgments about Aesha and other colleagues who wanted more balance. She started to notice her bias in action. When a colleague wasn’t fully committed to work, for example, Heather would look for other evidence to support this conclusion—maybe it was that they took an extra lunch break, or were sick one day, or that they took a bit too long to finish an assignment. Heather really did not want to do this with Aesha, so she made a special effort to look for supporting evidence that the colleagues she had previously judged negatively actually were committed to their work. She was surprised that once she started looking, she found more positive clues quite easily.

Heather was kicking herself now. Why had she treated Aesha’s text about work-life balance so lightly? She could see, in retrospect, how she had shut Aesha down without a second thought. There could have been so much more learning for both Aesha and Heather if Heather had acknowledged Aesha’s need to discuss this topic and gotten curious about why the demands of family life might have been such a pressing concern for Aesha.

Assumptions

Everyone holds assumptions about how the world works, and we view life through these filters. We take action based on our assumptions, and therefore they become “our truth.” But (and this is an essential point to recognize) they are not necessarily the truth in any given situation. In the mentoring relationship, our assumptions about what is true, what is appropriate, and how people should behave can prevent us from seeing what is true about ourselves, our mentoring partners, and the environments in which we work.

In the following example, notice how assumption affects perception. When she was practicing law, coauthor Lisa sometimes represented clients seeking asylum in the United States. In order to have a successful claim, asylum seekers must demonstrate that they have a credible fear of persecution if they were to return home. If the fear could be deemed reasonable by a judge, the client’s claim might succeed. If not, it would likely fail. When she met these clients for the first time, Lisa’s first task was to assess whether they were telling the truth about their fear of returning home.

Lisa was raised in the United States and shared a common cultural assumption that people who are telling the truth look you in the eye and people who are lying will avert their eyes. When she first met Katherine, a client from Uganda, Katherine did not look her in the eye. Automatically, Lisa concluded that Katherine was not being truthful. She judged everything she heard from that point forward through the lens that Katherine did not have a credible claim. Fortunately, Katherine was naturally skilled in cultural competency. Not too far into the conversation, she paused and said, “I want you to know why I am looking down. Americans make eye contact out of respect. In my culture, when you are in the presence of someone you respect, you do not meet their gaze. It is therefore difficult for me to look you in the eye.” Katherine’s astuteness was a check on Lisa’s assumptions. Once this difference was called out, Lisa was able to listen to Katherine’s story with an open mind and represent her in her successful claim for asylum.

All of us, inevitably, have assumptions about others and about our roles that guide our behavior and contribute to us forming conscious and unconscious bias. The key to understanding our assumptions is to bring them to the surface so we can test them for validity and challenge them if necessary. Adult educator Stephen Brookfield talks about the process of “assumption hunting.”37 He breaks it down into three interrelated phases: (1) identifying assumptions, (2) checking them for accuracy, and (3) acting in a more inclusive and integrative way.

Assumption hunting is especially important in a mentoring context. No mentoring partner is well served if they are in a mentoring relationship that is based on misunderstanding. Relying on invalid assumptions can undermine mentoring relationships by making them vulnerable to missteps and misinterpretation. Assumptions are woven deeply into what we consider normal behavior, so assumption hunting can be challenging. Yet, actively seeking to identify them is essential because it helps us realize the judgments we unconsciously make when reality differs from our assumptions. Aesha assumed that her mentor would understand her concerns since they were both working women. Heather assumed that if Aesha wanted to succeed, her mentee would need to make the same career choices that she had.

Testing out assumptions with your mentoring partner—about each other and about your roles as mentor and mentee—is essential. In the long run it will help you manage and meet each other’s expectations and avoid missteps. Untested assumptions can undermine trust and communication, and they can perpetuate bias, judgment, and misunderstanding. Assumption hunting helps raise awareness about why we do things. We’ll talk more about this in the next chapter.

» YOUR TURN «

1. If someone were to view the visible part of your iceberg, what assumptions might they make about you?

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

2. What assumptions do you have about the role of a mentor and the role of a mentee?

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

3. What assumptions do you have about the way your mentoring partner should approach the mentoring relationship?

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

Table 5.1 lists some assumptions that mentors and mentees often mention in our workshops. Do any of these resonate with you?

Curiosity

Once you have uncovered some of your assumptions about your mentoring partner, the next step is to test those assumptions for accuracy. To do this, you must use some constructive curiosity. This is not being nosy. Genuine curiosity springs from your authentic desire to understand something more deeply. Earlier in this book we cited a Harvard Business Review article that defined curiosity as “a penchant for seeking new experiences, knowledge, and feedback and an openness to change.”38

TABLE 5.1 Common assumptions about mentoring

Assumptions about the role of mentee |

Assumptions about the role of mentor |

Assumptions about mentoring |

» The mentee knows what they want from mentoring. » The mentee has clear goals. » The mentee is looking for answers from the mentor. » The mentee has to follow the mentor’s advice. » The mentee aspires to be like the mentor. » The mentee wants to rise in the organization. » The mentee will dedicate the time necessary to make the most of mentoring. |

» The mentor has the answers. » The mentor wants the mentee to succeed. » The mentor will be available whenever the mentee needs them. » The mentor understands the mentee and the mentee’s motivation. » The mentor has mentored before and understands what is needed to be a good mentor. |

» Mentoring doesn’t require much preparation. » I’ve been in a mentoring relationship before, so I know how to do it. » I know how to manage people, so I will be a good mentor. » Mentoring is the key to promotion. » Mentoring is organic and just develops over time. |

Source: Authors.

The authors of that article found that curiosity is the best predictor of leadership competency and that, if appropriate developmental opportunities are offered, curious leaders are usually able to advance to C-level roles.39 A mentoring relationship can be an excellent laboratory to cultivate curiosity and find the right developmental opportunities. “Curiosity,” say these authors, “reduces our susceptibility to stereotypes and to confirmation bias.”40 We have found that curiosity boosts business performance as well as mentor and mentee performance. It inspires mentor and mentees to develop more trusting and more collaborative relationships with one another.

Behavioral scientist Francesca Gino found that “when our curiosity is triggered, we are less likely to fall prey to confirmation bias and to stereotyping people.”41 Curiosity encourages members of a group to put themselves in one another’s shoes and take an interest in one another’s ideas rather than focus only on their own perspective.42 Mentoring partners can encourage curiosity simply by being inquisitive. When a mentor or mentee asks questions instead of presuming to know answers, they are practicing what Gino calls “intellectual humility”—the ability to acknowledge that what they know is limited. This, of course, requires a growth mindset (discussed in Chapter 2). Curiosity is especially important when faced with situations, attitudes, or behaviors we don’t understand. By exercising curiosity (that is, proactively practicing it), we seek to get more information before we reach conclusions, minimizing the extent to which we judge our mentoring partners and allowing us to suspend judgment so that we can better understand and appreciate differences.

As Heather would have discovered if she had taken the time to get to know Aesha more deeply, Aesha deeply values family. In Aesha’s cultural framework, as a daughter-in-law she is expected to care for her husband’s visiting parents during what many Americans might view as a very lengthy stay. Aesha understands this, accepts her role, and is happy to host her in-laws; but she does wonder how she is going to get everything done that she needs to do. Fortunately, though Heather was initially dismissive of Aesha’s concerns about meeting family obligations, Heather eventually got curious about the pull that family obligations had on Aesha.

As Heather gradually understood that Aesha’s concerns were deep and real, the dynamic between them started to shift for the better. Heather, who had been judgmental and mildly annoyed about Aesha’s early insistence that they address “balance,” began to see the influence of Aesha’s culture on her sense of familial obligation. Heather suddenly understood that Aesha couldn’t be comfortable making the same choice Heather had when weighing work and family obligations. More important, Heather started to question whether that would even be essential for Aesha’s success. Aesha gave a deep sigh of relief as she saw that Heather was beginning to understand Aesha as an individual rather than a Heather clone.

Creating space within your mentoring relationship to ask questions and explore answers helps cultivate curiosity and accelerate getting to know one another better. Many mentoring pairs we coach set aside time at the beginning of each meeting to ask each other “power questions” that will help them understand what makes the other tick. Some questions they have come up with include: “What is an ideal day?” “What is your superpower?” and “What motivates you?” While general catch-ups can be helpful in mentoring conversations toward building trust, questions like these go a bit deeper and allow mentoring partners to connect in a way that encourages further questions and dispels judgment.

» YOUR TURN «

1. Think of a time when you felt curious about someone. How did you demonstrate your curiosity? What prompted your curiosity?

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

2. With your mentoring partner, brainstorm a list of power questions to use to get to know each other better and cultivate an environment of curiosity. Set aside five minutes at the beginning of each meeting for each of you to answer one power question.43

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

3. Practice curiosity. Find one opportunity each day to reframe a statement into a question and really listen for the answer. What do you notice?

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

Asking Questions

Good questions are critical in expressing curiosity, generating conversation, creating developmental relationships, building networks, and developing trust. James E. Ryan, dean of the Harvard School of Business, suggests six questions that are “everyday staples of simple and profound conversation.”44 We focus here on four of those questions that are particularly germane to mentoring.45

Wait, What?

Ryan’s first question is—”Wait, what?”—and it’s easy to understand why. “Wait” signifies a pause. “What” begs clarification. Asking “Wait, what?” is an effective way of clarifying thinking and it invites others to do the same.46 It reminds us to slow down and wait, to make sure we truly understand what’s being said before we act/react. According to Ryan, “Wait, what?” is a clarifying question that is at the root of all understanding.47

I Wonder If . . . ?

The second question—”I wonder if . . . ?” or “I wonder why . . . ?”—lies at the heart of all curiosity. It is useful for both mentoring partners because it invites a level of engagement that deepens the conversation. It is how we prompt ourselves and others to try something new, and how we deepen our understanding of one another’s motivations and perspectives.

These questions are particularly important when our mentoring partners’ approach or mindset is different than our own. Summoning a sense of wonder can heighten our awareness and help us come up with more innovative, tailored, and sticky solutions. Aesha wondered why Heather kept dismissing her request to talk about balance. She sensed it was a taboo topic, but it wasn’t until she asked “why?” that she started to understand Heather better.

Couldn’t We at Least . . . ?

The third question—”Couldn’t we at least . . . ?”—is another power question. It’s a great way to get unstuck because merely asking it helps create common ground and triggers other questions. Best of all, it keeps people in conversation. Ryan sees this question as the “heart of all progress”; by sparking momentum it keeps us moving forward. “It is the question,” he says, that “recognizes that journeys are often long and uncertain, that problems will not be solved with one conversation and that even the best efforts will not always work.”48

How Can I Help?

The fourth question—”How can I help?”—is the foundation of all good relationships. “How you help matters just as much as that you do help,” Ryan explains, “which is why it is essential to begin by asking How can I help? If you start with this question you are asking with humility for direction. You are recognizing that others are experts in their own lives, and you are affording them the opportunity to remain in charge, even if you are providing some help.”49

Mentors, this is a great question, and you may be tempted to start your very first mentoring session by asking it. Beware that your mentee may not yet know what they need, nor have you built enough trust for them to feel comfortable answering you honestly so early in the relationship.

How to Ask Good Questions

Good questions are expansive. They unlock possibilities, set the stage for deeper conversations, and build trust. Ryan’s questions are a good start, but curious people should ask many more questions. Sometimes the most generative response to a mentoring partners’ statement is a question that seeks to go deeper. Such questions can elicit more facts, or seek to create a deeper understanding of mindset, feelings, and rationale. We’ll explore some of these types of questions below.

Probing questions usually start with what journalists call the 5W1H: What? Where? Who? When? Why? and How? These open-ended questions are designed for fact-gathering—they cannot be answered with a simple yes or no. (Will? or Did? questions are closed because they solicit a yes or no answer that effectively ends the conversation.) Effective probing questions create shared understanding of what actually occurred.

For example, Heather might ask her mentee: Who might you need to involve in helping you with the design of your presentation? What happened when you pitched your deck to the senior leadership team? When or where did the pitch take place? Why did you feel uncomfortable sharing the deck with your supervisor in advance? How will you follow up? Aesha might ask Heather: Who were your mentors? What support did they provide that made a difference in your career? When did you feel like you had gained enough experience to lead a team? Where did you feel you made the biggest difference in the company? How did you build your network?

Since conversation is not interrogation, both mentor and mentee can use probing questions to illuminate issues. Once you have gathered sufficient information through probing questions, you might use clarifying questions to create mutual understanding about the facts. Clarifying questions are also open-ended. They are designed to help us understand motivation, behavior, and context around the facts. These questions acknowledge the information received from the probing questions and dig deeper. The best clarifying questions begin with a statement that paraphrases the information received and then uses that information as the basis of the next question. For example:

» “It sounds to me like you are saying that you are getting mixed signals from your manager about what she wants you to do next.” (Paraphrasing) “Is that correct?” (Clarifying)

» “You feel really conflicted about pursuing this project.” (Paraphrasing) “What does that mean for you?” (Clarifying)

» “I can tell you need some clarity around this.” (Paraphrasing) “How do you define that?” (Clarifying)

Clarifying questions can also be quite useful when you don’t understand or when you disagree with your mentoring partner. Be sure your question seeks clarification but does not appear judgmental. For example: “I hear that you are concerned that your manager isn’t pleased with you.” (Paraphrasing) “What about her reaction makes you think that?” (Clarifying)

Avoid at all costs the judgmental version of these interactions: “I hear you are concerned your manager isn’t pleased with you. I think you’re reading it wrong.” Or, “I understand you feel concerned, but I don’t think you should feel that way.” We are so used to making judgments that it becomes automatic to offer our opinions. It can be difficult to switch from a position of judgment to clarification, yet doing so is vitally important to your relationship. A question asked with judgment will result in (a) either a nonresponse or (b) a defensive answer or (c) an answer that is crafted to appease your judgment. In any of those cases, judgment contracts and hampers trust. Making the switch takes awareness and practice, but it’s a critical skill for both mentors and mentees to learn and use.

Listening

As thought leader Stephen Covey said, “Seek first to understand and then to be understood.”50 This is the key to listening, and listening is the key to asking good questions. Good listening demands our full attention. It requires paying attention to the other person’s words, intonation, and body language from start to finish. When you are listening well, you are not already planning what you are going to say in response while another person is speaking. Rather, you are listening all the way until the end and responding to what you actually heard.

Significantly, good listening also requires that you pay attention to cultural context. You will need to be aware of your mentoring partner’s preference for direct or indirect communication. Individuals with a preference for direct communication tend to prefer precise and explicit language, put value on speaking their mind, and prefer to verbally assert their difference in opinion. The meaning in their conversations is conveyed primarily through words.51 For individuals with a preference for indirect communication, the meaning comes from the surrounding context, and the speaker often leaves it to the listener to pick up the clues. Both styles can be effective, but it is critical to good listening that you know your own preference and recognize (without judgment) the style of your mentoring partner.

Coauthor Lisa’s cultural preference is direct communication, which was commonplace when she lived in Chicago. But when she moved to her company’s Pacific Northwest location, she encountered a stark cultural divide. There, the general organizational culture was more indirect. In her first few weeks at the new location, Lisa presented a strategic plan on a diversity initiative to a meeting full of stakeholders, hoping to seek alignment so she could roll out the plan. When she was done presenting, the room was quiet but the attendees all nodded their heads. Lisa asked if there were questions or concerns, but there were none. Several attendees gave her a thumbs-up. She left the meeting feeling like she had agreement.

Once Lisa started to implement the initiative, however, one of the stakeholders approached her to say they were not in fact aligned with the initiative. Lisa felt blindsided and confused. After all, there had been head nods and thumbs-up but no objections or questions. Lisa learned quickly (and the hard way!) that in this culture head nods and thumbs-up can mean “I hear you” and “I understand,” not necessarily “I agree” or “I am aligned.” The silence and lack of questions were meant to be indirect signals of lack of agreement, not assent. Now Lisa uses this awareness to “listen” to the silence and more explicitly state her understanding.

Have you ever been in a conversation where the other person said something that you couldn’t understand, but you nodded as if you understood so that you didn’t have to ask for clarification? This happens to many of us, and the intent is often well-meaning (for example, to avoid embarrassing the other person, because you have a hearing impairment, to save time, to not be “rude” by asking the other person to repeat). However—particularly when the native language of mentoring partners differs, or when one member of a mentoring partnership has an accent or speech impediment, and particularly when someone is sharing something personal—ask them to repeat what they said. The conversations in mentoring are deep and important. Pretending to understand can later result in the person feeling dismissed, ignored, or misunderstood. Take the time to ask for clarification.

Here are a few other rules of good listening:

» Good listening requires you to minimize distractions. Obvious distractions are email and phones. Often people will have their phones out but turned over on the table in front of them. Research has shown that the mere presence of a cell phone or smartphone can lessen the quality of conversation, reducing the amount of empathy exchanged.52 Best practice? Put your phone out-of-sight.

» Good listening requires that you listen all the way to the end before you comment. Do you often find yourself nodding while formulating your response to something someone is saying? When you do this, you miss the full context of what is being said. Instead, wait until the end and take advantage of a good long pause to determine how you wish to respond.

» Good listening requires that you listen to understand, not to wait for an opening. Good conversations are not a game of ping-pong, where participants alternate speaking one after another. To be responsive requires you to be fully in the conversation, and not waiting for your chance to get a word in.

» Good listening requires paying attention to tone, body language, and facial expression, not just to the words used (Table 5.2). In a well-cited study, psychologist Albert Mehrabian found that when people talk about their feelings or attitudes, the meaning of a message is conveyed significantly more by tone of voice and body language than by the words used by the speaker.53

TABLE 5.2 Body language matters

What we do |

Level of influence |

Our words |

7% |

Tone of voice |

38% |

Body language |

55% |

Source: Mehrabian, Silent Messages.

» YOUR TURN «

1. If you were to give yourself a grade as a listener, what would it be and why?

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

2. What are your strengths as a listener?

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

3. What are three specific actions you can take to strengthen your listening skills over the next ninety days?

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

Preparing the mentoring relationship requires mentoring partners to learn about one another, seek clarification, and build trust. This happens only by cultivating curiosity, asking questions, and deep listening. In the next chapter, we’ll explore the fine art of simply getting to know one another.

Chapter Recap

1. Sometimes we think we are having a conversation, but we are really engaged in a monologue or a transaction. Mentoring conversations should strive for higher levels of conversation: collaborative engagement or dialogue. The higher the level of conversation, the more it promotes learning and deepens trust.

2. Since we act on our assumptions, we need to test them out and see if they are valid before we come to a conclusion. This is particularly important when it comes to cultural context. Listening for context requires curiosity. Curiosity requires intellectual humility and a growth mindset.

3. There are many types of questions we can ask to generate conversation and develop trust. Mentors and mentees should practice the art of asking the good questions.

4. Good listening requires that you minimize distractions, listen all the way to the end, listen to understand, and pay attention to tone, body language, and facial expression.