2 THE CONTEXT FOR UX (1)

Rationale and Concepts

What sort of thing is happening here?

Cutting Edge, Graham Taylor (1994)

INTRODUCTION

This chapter discusses:

- What sort of thing is user experience?

- How does UX relate to customer experience, usability, accessibility, user-centred design, human-centred design and service design?

- What is the business case for UX?

- Why is UX important?

- Why is UX different?

WHAT SORT OF THING IS UX?

At the most fundamental level, the term ‘user experience’ means exactly what it says. That is, as ISO 9241-210 (2019) puts it:

[A person’s] perceptions and responses that result from the use and/or anticipated use of a system, product or service.

As this suggests, user experience at the most basic level is a set of subjective psychological events and states (perceptions) experienced by an individual and immediately accessible only to the person in question. We may gain an insight into those events and states by seeing how the individual speaks and (re)acts (their responses).

Another definition, by the Nielsen Norman Group (n.d.), takes a more objective and impersonal perspective: ‘All aspects of the end-user’s interaction with the company, its services, and its products’.

Although this formulation has not moved far from the first one, the focus has moved away from the individual’s inner world, towards an observable set of interactions. The user’s own subjective point of view is just one part of an overall reality, all of which is amenable to objective analysis. This small shift in perspective has significant implications. If we can describe and analyse elements of the user’s experience objectively, we may also be able to influence that experience in a controlled way. However, it would be going too far to suggest that we can ‘design’ a person’s experience. The most we can hope for is to design parts of the context within which that experience takes place.

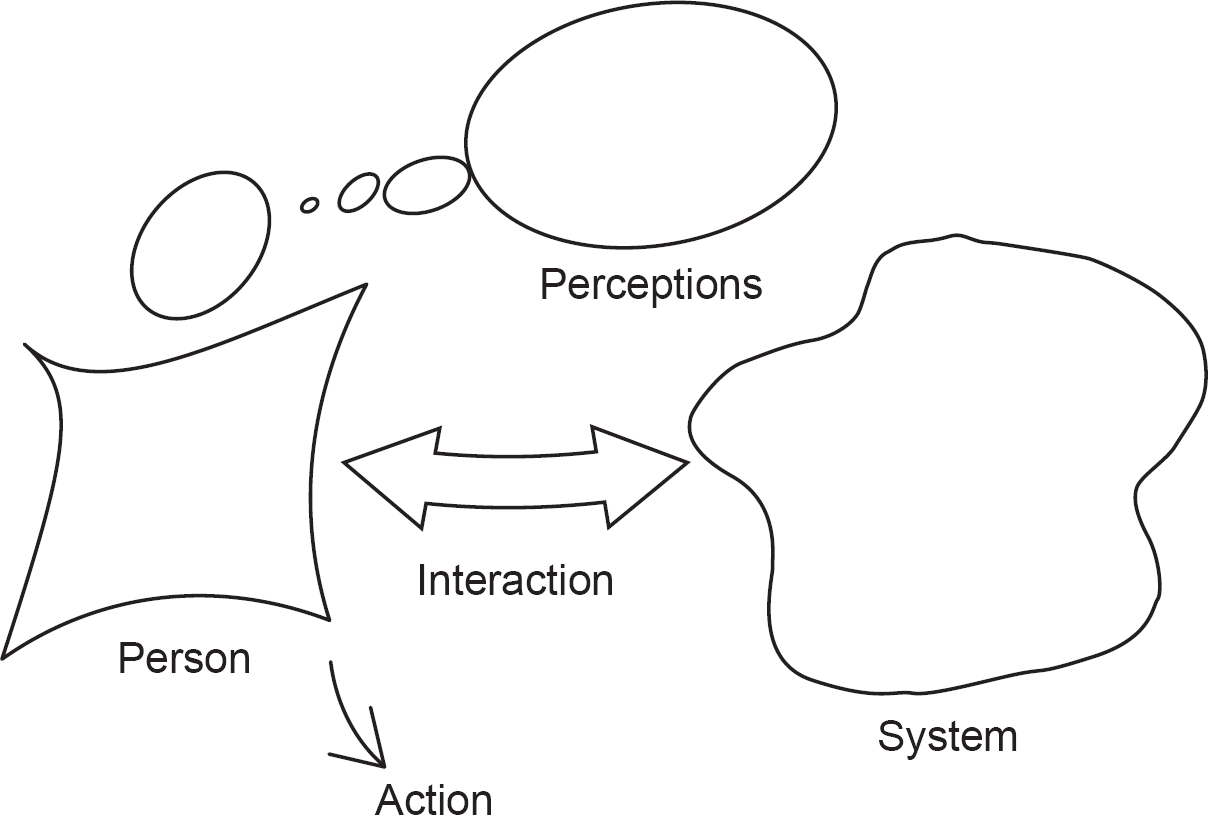

Key elements of UX

We can see five key elements in the definitions above:

- A person – that is, the user.

- A system, whether viewed comparatively narrowly as a product or software application, or more broadly as a service, organisation or brand.

- Use of, or interaction with, the system by the person.

- The perceptions of the person resulting from their use of the system. These are mainly psychological phenomena, potentially of some complexity, but might also stem from physiological factors. For example, they might include some kind of physical discomfort resulting from use of the system, or a feeling of frustration induced by the physical difficulty of operating the system’s interface.

- The person’s responses resulting from their use of the system. While internal emotional responses are relatively hard for an observer to detect and analyse, many responses are behavioural and can be clearly seen in the person’s actions.

These elements can be seen graphically in Figure 2.1. Note that the ‘system’, even if it exists most obviously as a technical artefact, such as a piece of hardware or software, always contains other elements such as people, services, rules, procedures, cultural assumptions and so on. These elements are sometimes overlooked but often play a decisive part in the nature and quality of the user’s experience.

Figure 2.1 Basic model of UX

Products, services and systems

In this book, we will sometimes refer to ‘products’, ‘services’ or ‘systems’. Wherever one of those terms in used, the discussion is equally relevant to products, services or socio-technical systems in the broadest sense. The applicability of the principles described is much wider than a single product. A mobile app, an enterprise IT system or a call centre-based support service would all be examples; equally, an entire organisation, or a service provided by one or more organisations, can and should be considered a system from the perspective of the customers’ experience. Although human-centred design originated as a way of designing individual artefacts, it is equally powerful when applied to systems on a larger scale.

Similarly, when we refer to the user interface, we are not just talking about a software system’s input and output of data via a screen, speakers or microphones. It can include conversations with people, information that is displayed on posters or disseminated through advertisements, the physical delivery of goods and so on.

All these types of products and services can be thought of as examples of what ISO 9241-11 (2018) calls an interactive system, defined as ‘a combination of hardware and/or software and/or services and/or people that users interact with in order to achieve specific goals’.

The key elements of UX in more detail

Why are we interested in the nature of someone’s experience of a product? The answer, of course, is that we want to make it better in some way – or, if the product does not yet exist, to design the product so that the experience will be a good one. To support that aim, we first need to expand our basic model of UX to include some more elements.

Intentions: goals and tasks

First, the person’s use of the system does not happen by chance. There is a reason for it. People are purposeful creatures. They interact with software systems or companies because they want something; the interaction is a means to an end. The system’s usability and the quality of the user’s experience cannot be evaluated without taking the user’s purposes or intentions into account.

It is helpful to distinguish between two kinds of intention, most commonly referred to as goals and tasks. The user’s goals are the outcomes that they want to achieve, and they believe engaging with the system may help them to attain those goals. Tasks are the things that the user needs to do in order to achieve their goal. If we are creating a new technical solution to help people achieve a particular goal, we will first study and understand the tasks that they must currently carry out to that end, and later we will design new tasks that will result in the goal being reached in a different but better way. At a lower level of detail, we can identify individual cognitive or motor operations making up the task that must be carried out using the interface that we are creating. Donald A. Norman (2005) suggests a four-level task hierarchy composed of activities, tasks, actions and operations. As Alan Cooper et al. (2014) point out, these are all subordinate to goals.

Goals and tasks are common-sense ideas that map easily onto the concepts of the same name in requirements engineering, business analysis and systems analysis. Other words that are sometimes used for goals are aims, objectives or needs. A more troublesome near-synonym is requirement, which we will discuss later in this chapter and in Chapters 3 and 5. A near-synonym for tasks is activities.

Goals are discussed further in Chapters 4 and 5, where we consider different ways of classifying and documenting them.

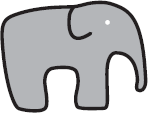

Predispositions

Second, we must acknowledge that we can only hope to gain a good understanding of the user’s perceptions and responses if we are prepared to investigate and model their subjective world in some way. People vary, and we need to think carefully about the ways in which they vary in order to identify groups whose needs we will try to meet, and groups whose needs we will not try to meet. Interaction with a system is reflexive: in other words, not only is each user predisposed to perceive their interaction with the system in a particular way, but also the experience of the interaction will modify those predispositions and influence their future perceptions (see Figure 2.2).

Figure 2.2 Extended model of UX

Attributes of people that we may need to model include (but are not limited to) experience, knowledge, skills, attitudes, motivations, values, expectations and dispositions, as well as their physical abilities. In Chapters 4 and 5 we discuss how to do this.

Environment

Third, use of a system does not happen in a vacuum. The physical environment in which the interaction takes place will impose constraints on the design. Systems are often created on the basis of assumptions about the environment or a relationship to it. These assumptions may not be well-founded. For example, a designer working in a comfortable studio may forget that the user could be in an environment with noteworthy levels of temperature, light, humidity, space, movement, noise or stress. The user may be unable to speak the local language, or to speak at all. The user may be unable to perform the motor or cognitive operations required by the design.

One aspect of the environment that is often particularly important to designers is the technical environment – the set of tools with which the user engages, or which constrain and influence their behaviour.

Social setting and structure

Fourth, although the classical model in human–computer interaction is of one person interacting with one computer, this does not capture the complexity of the real world. In particular, we often need to pay attention to the fact that the user is working as part of a social group of some sort. Very often there will be structure associated with the group, as in the case of a department within an organisation.

The concept of goals is useful in thinking about this situation. To the extent that they can be agreed on, whether explicitly or implicitly, some goals are shared by multiple individuals within an organisation. While tasks are best thought of as something relating to one individual at any given time, shared goals are part of people’s shared reality and can help us to design for successful user experience in an organisational setting.

The social setting may also include other people who do not share the user’s goals. Indeed, they may have other goals that are in conflict with the user’s goals.

These further elements of UX are reflected in Figure 2.2.

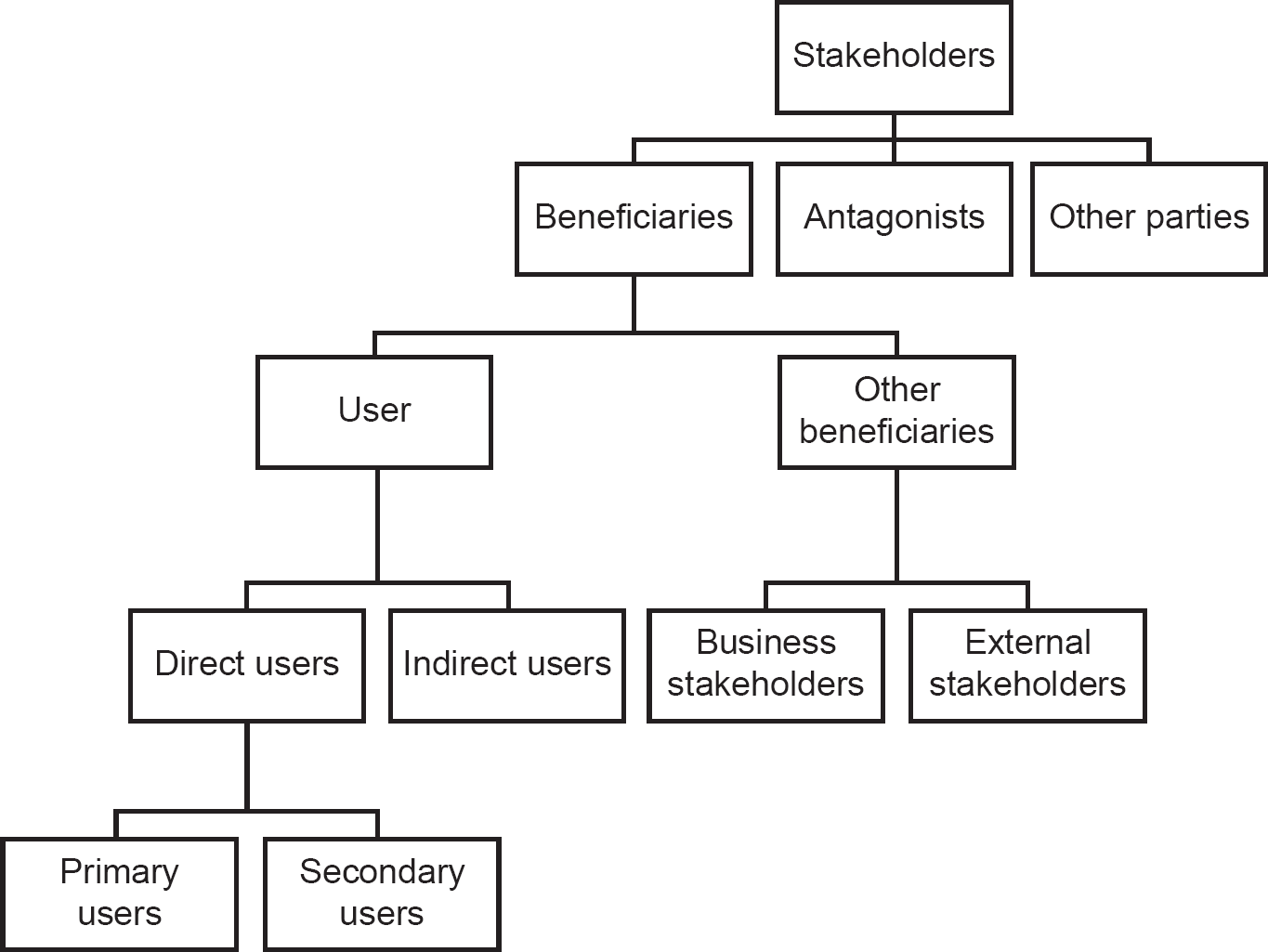

WHO IS THE ‘USER’?

As we have seen, we generally refer to the people whose needs we are concerned with meeting as users. Accordingly, ISO 25010 (2011) defines a user as any ‘individual or group that interacts with a system or benefits from a system during its utilisation’. This definition covers a wide spectrum of ways in which people can relate to a system. ISO 9241-210 (2019) uses the term ‘human-centred’ rather than ‘user-centred’, emphasising that it is not just direct users of the system whose perspective must be taken into account.

ISO 25010 (2011) makes a distinction between direct and indirect users. Direct users are people who interact with the system. Indirect users do not interact with the system, but receive output from it.

Direct users can be divided into primary and secondary users. The primary users of the system are the people who use it to support their achievement of primary goals, whereas secondary users only interact with the system in the course of providing some kind of support function.

It is worth noting that there are also often people who benefit from a system during its utilisation who neither interact with it nor receive output from it – for example, shareholders in a software company.

Stakeholders

Equally, there are people whose perspective needs to be taken into account in designing a system besides those who benefit from it during its utilisation. The concept of stakeholders is useful here. ISO 15288 (ISO/IEC/IEEE 15288, 2015) defines a stakeholder as ‘an individual or organisation having a right, share, claim or interest in a system or in its possession of characteristics that meet their needs and expectations’. This includes anyone to whom the system represents an opportunity or a threat – for example, competitors.

Two meanings of ‘stakeholder’

A stakeholder is any individual or organisation having an interest in a system or its characteristics (ISO/IEC/IEEE 15288, 2015).

A user, in the narrowest definition, is a person who interacts with the system (ISO 9241-210, 2019).

To be strictly accurate, then, users are a subset of stakeholders. All users are stakeholders, but not all stakeholders are users.

In a UX context, ‘stakeholders’ is often used (for example, by Garrett, 2010 and Goodwin, 2011) to mean exclusively ‘business stakeholders’, as distinct from users, that is, people who have a business interest in the system but who are specifically not its users.

Figure 2.3 shows how the different categories of users and stakeholders relate to each other. There are two important points to be made regarding this hierarchy.

From a project management and marketing point of view, the chances of project success will be improved if the perspectives of all the stakeholder groups are considered.

However, to create a good product, it is absolutely essential that the design should be guided by the needs of the primary users, without it being compromised by the preferences, opinions or prejudices of other stakeholder groups.

Figure 2.3 Users and stakeholders

If truth be told, the terms ‘user-centred’ and ‘human-centred’ sometimes describe an aspiration rather than reality. A project is only truly human-centred when it is focused on meeting the users’ needs without regard to the type of solution. In practice, when design teams are working on a product, the thing that is often really at the centre of the stage – even when it does not yet exist – is the product itself. A more accurate term in these cases might be ‘people-oriented design’ (de Voil, 2013). In any human-centred design process, the users and other stakeholders are decisively important, and the whole process is oriented towards them.

UX AND USABILITY

The ISO standards have tried to keep the concepts of UX and usability distinct from each other, by stressing objectively measurable factors in the definition of usability while emphasising the subjective nature of experience in the definition of UX. However, most practitioners would agree that UX is the broader concept and that usability is a part of the overall user experience. Usability is discussed in detail in Chapter 6.

UX AND ACCESSIBILITY

As mentioned earlier, people vary. We need to avoid accidentally or deliberately designing systems that are difficult or impossible for some people to use because of assumptions that are built into them about users’ physiological or cognitive attributes. This is harder than it sounds, because making assumptions about other people is a fundamental and normal thing for human beings to do. Accessibility, discussed further in Chapter 11, is the property of a product or system that refers to this. The key to creating accessible systems is inclusive design, discussed further in Chapter 3.

Often there is a need to design a digital service, that is, a service that is accessed over the internet. To most users, digital services offer compelling advantages, such as convenience, speed, choice and low cost. However, there may be some users of the service who are unable to access it unaided, if at all. This may be because of physical or cognitive disabilities, learning difficulties, language skills or simply lack of access to technology or the ability to use it. To ensure that these users are not excluded from using the service, it needs to include appropriate assisted digital support. This means helping people to use the digital service by providing support, for example in person, on the telephone or via web chat. It is an alternative to designing separate versions of the service, delivered over different channels, for different classes of user.

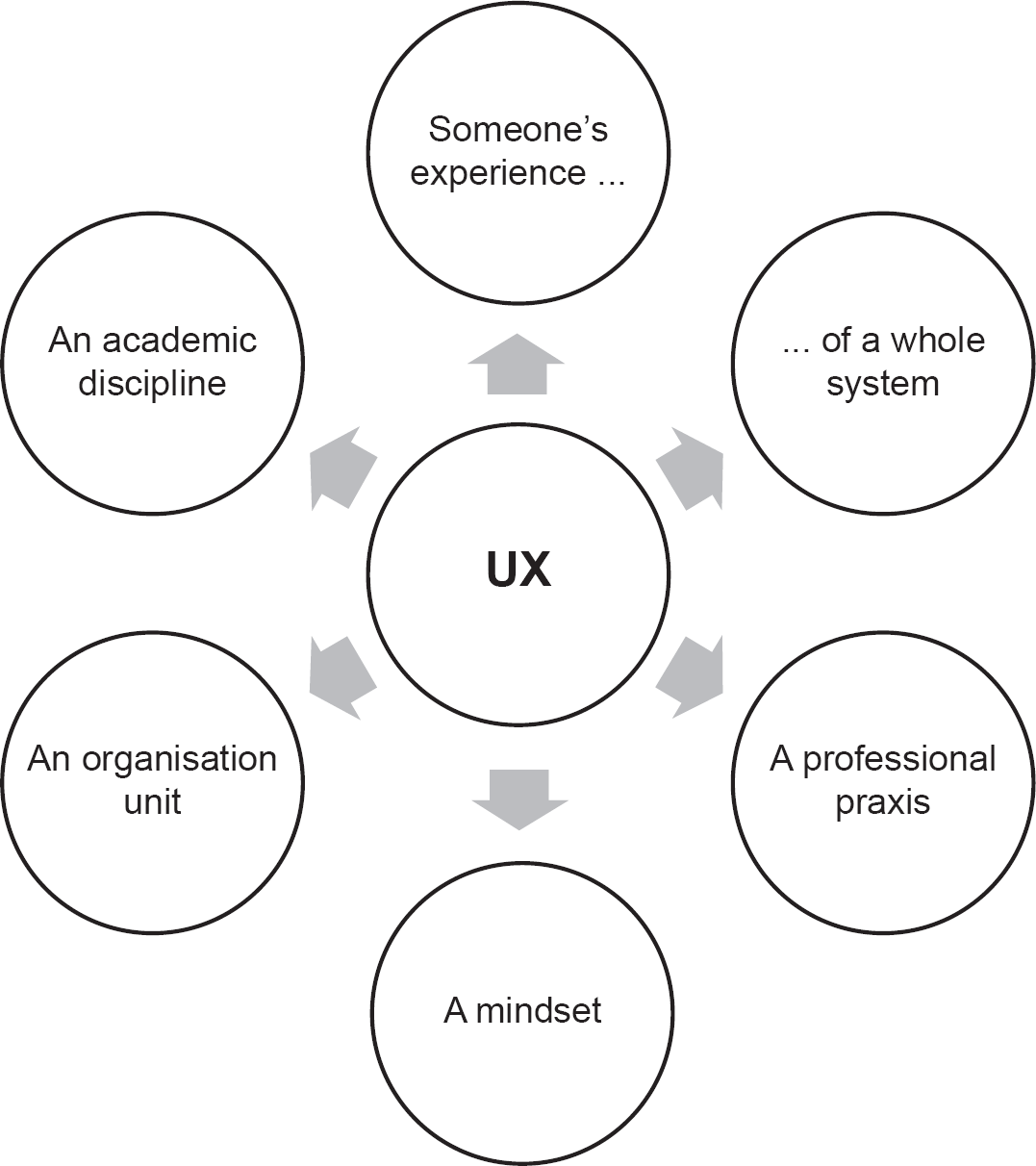

EXTENDED MEANINGS OF ‘USER EXPERIENCE’

The term ‘user experience’ suffers from a bad case of metonymy, the practice whereby people use a word to refer by extension to something different but related. This is one of the reasons why discussions about UX often seem to go around in circles with no evident progress towards mutual understanding. As summarised in Figure 2.4, ‘UX’ is used to refer to all of the following:

- A set of professional practices. We might say that someone is ‘doing UX’.

- A professional community including people who are employed in a more or less well-understood set of roles, such as user researcher, information architect or interaction designer.

- A set of specific techniques that are used, such as contextual observation or usability testing.

- The set of competencies that someone using those techniques or employed in one of those roles needs, for example, usability test moderation or interaction design.

- A set of work products that are typically produced by people engaged in user experience design, such as persona descriptions or wireframes.

- A mindset. A colleague might say that someone is ‘not really doing UX’ because she believes they are paying lip-service to UX practices without wholeheartedly subscribing to our view of the authentic UX philosophy.

- An organisational unit, whether in the general sense of a function that is to be found in many organisations, or in the particular sense of the specific individuals employed by that function in one organisation.

- An academic discipline. The academic discipline relating to UX is more often referred to as human–computer interaction (HCI).

Figure 2.4 Possible meanings of ‘user experience’

MISLEADING USES OF ‘USER EXPERIENCE’

‘UX’ is also sometimes used with the intention of denoting an intrinsic attribute of a product or system, as in: ‘This app has a poor user experience.’ Strictly speaking, this is an inappropriate use of the term. As we have seen already, the user’s experience is a phenomenon that emerges from the interaction between the user and the product. It is not inherent in the product itself.

Particularly in a recruitment context, the phrase ‘UX/UI design’ (user experience/user interface) or ‘UI/UX design’ is often heard. User interface design is actually a sub-discipline of user experience, and so this formulation represents what logicians call a ‘category error’, which inappropriately seeks to place two concepts on the same level when one is in fact subordinate to the other. It is a particularly pernicious mistake, because its take-up and usage help to perpetuate confusion about the field’s basic concepts.

HOW DOES UX RELATE TO OTHER DISCIPLINES?

In this section, we look at the similarities and differences between UX and related disciplines at a high level.

Marketing

For decades, marketing professionals have been attempting to increase sales by understanding customers and their preferences, using tools such as surveys, psychographic profiling, focus groups and Voice of the Customer programmes. Clearly, there is an overlap between the concerns of marketing and UX, and some of the techniques used are superficially very similar. However, the underlying mindset is completely different. The marketing discipline is focused on maximising sales. UX is focused on meeting people’s needs. However, UX projects are often sponsored by marketing departments. In these circumstances the UX design team must be prepared to put time and effort into evangelising for the human-centred approach and its associated business benefits.

Customer experience

Customer experience (CX) is a discipline that has developed from marketing. CX professionals analyse and try to optimise the experience of a company’s customers over time and with reference to specific touchpoints and channels. Bearing in mind the second definition of UX that we looked at earlier, we can see that CX and UX are similar in their scope and aims. However, the marketing culture and mindset is still evident in CX. To put it simply, marketing is about finding customers for a product, whereas UX is about designing products that will help customers.

As we have seen, there is a wide range of relationships that people may have to a product or service, which come under the general heading of ‘user’. A customer relationship is one of these. The customer is the person who makes the purchase decision. By definition, therefore, UX is a broader spectrum than CX because it covers other perspectives besides this.

Business analysis

Business analysts are concerned with finding solutions to business problems. A large part of their work, as well as that of related disciplines such as systems analysis and requirements engineering, is about discovering what users need. The key difference is one of perspective. While business analysts tend to put the needs of the business stakeholders first, user experience researchers are primarily focused on the direct users and their needs. A distinction is sometimes made between ‘business requirements’ on the one hand, and ‘user needs’ on the other. It is fair to say that business analysts are more concerned with the first of these, and user experience researchers with the second. However, the difference can be overstated: business analysts also need to understand user needs, and UX researchers also need to understand business needs.

If users’ experience with a system is bad, then the system is a failure. It may be a technically excellent product from an engineering point of view, but that is of no value if people cannot use it or do not find it an effective way of achieving their goals. User-centred design aims to mitigate this risk.

We also need to consider the bigger picture. As ISO 9241-210 (2019) puts it,

Products, systems and services should be designed to take account of the people who will use them as well as other stakeholder groups, including those who might be affected (directly or indirectly) by their use ... In modern society, a key issue is to encourage socially responsible designs ... integrating and balancing out the economic, social and environmental considerations.

Technology is woven into the fabric of our lives. Our ways of being, thinking and behaving are framed by socio-technical systems that have come into existence as the cumulative result of a series of small-scale and large-scale decisions made by people working in organisations, often on programmes of work that are conceived as IT projects. In effect, the makers of those decisions are designing the experience of all the individuals affected: not only the individuals who interact directly with the system’s technical elements via a user interface (primary users), but the people who are enmeshed in the web of consequences that spreads out, whether by design or not, from the way the system works.

An example of this is provided by companies that offer economic value to users through a business model based on disintermediation via mobile apps. Using an app, you might book holiday accommodation directly with the owner of a property, instead of using the services of existing participants in the holiday accommodation market, such as hotels; or you might book a taxi ride directly with the driver. Is this a simple story of technology meeting an unmet need via the magic of the internet? At first glance, it might look that way, but in fact that is not the case at all. At the core of this situation there is a technical artefact meeting a need, but there are effects that ripple outwards in ever-widening circles, with impacts on the employment market, social and political environment, taxation system and legal system, to name only a few areas.

The business case for UX

The business case for UX can be seen in terms of four levels. These are tactical cost reduction, project risk mitigation, product strategy and dynamic capability management.

At the cost reduction level, there are several well-established ways in which UX can reduce costs, for example:

- Saving operational staff costs by enabling staff to carry out tasks more quickly.

- Saving operational staff costs by enabling staff to carry out tasks more accurately, thus saving costs associated with remedying mistakes.

- Saving support staff costs by allowing customers to understand the product or service and use it effectively without help.

- Saving development costs by eliminating the need for custom-built user interfaces to be rebuilt because of usability defects.

At the risk mitigation level, UX can contribute by providing a process that greatly increases the probability of a usable and successful product.

UX can play a key role in product strategy. Products and services that are usable and genuinely meet people’s needs will ultimately – all other things being equal – be more successful in the marketplace and generate more revenue.

At the capability management level, UX is about understanding people and developing products and services that people want, through a process that allows the organisation to react to new information on a continual basis.

WHY IS UX DIFFERENT?

A human-centred approach to systems design differs from some more traditional approaches in its structural features – the activities required and the order in which they are performed – which are discussed further in Chapter 3. More importantly, a distinctive mindset is required. Here we pick out some additional underlying themes that go to the heart of why the approach of UX is different.

Relative importance of functionality

In a systems engineering approach to systems design, the most important thing is functionality. ‘Non-functional’ attributes and constraints such as usability are often considered to be of secondary importance, and consideration of them may be deferred until the scope and features of the system are already defined. Attention may be paid to the system’s ‘look and feel’, but this is overlaid on a design whose structure is driven by features and functionality. Software companies have traditionally competed on functionality; they aim to improve their competitive position by adding features, rather than maintaining their products’ level of usability. New features are sometimes chosen for their perceived value as technological innovations, rather than with direct reference to users’ needs.

In a human-centred approach, this order of priorities is turned on its head. Usability and usefulness are the most important product attributes, and features are only included if they contribute to those aims.

A concrete way of thinking

In systems analysis, the aim is to identify abstract concepts that can be accurately modelled as data, processes and rules within a computer system. Interaction with stakeholders during a project is implicitly organised to bring about this objective. The specifics of real-life situations are discarded as early as possible in this process. In so far as different individuals can perceive the same situation differently and describe it in differing terms, analysts try to neutralise or overcome that variety of perspectives. Once they have derived a formal model, they can use the tools of logic to develop, implement and test it.

In a human-centred approach, by contrast, we attach great value to the concrete, specific details of the environment that users inhabit and the activities that they carry out. Although we acknowledge that abstraction of concepts and standardisation of vocabulary need to happen eventually, we try to defer that to as late a stage as possible. We actively seek to identify the variety of ways in which different people think about the problem domain, and the range of language that they use to talk about it. A key attribute of many of the techniques described in this book is that they take data derived from multiple viewpoints and go about structuring it in ways that respect the users’ authentic ways of thinking, rather than forcing it into a logical form that prematurely takes over the design process.

The time dimension

This abstraction, or removal of context, which is typical of traditional systems analysis, has one particularly noticeable effect: the loss of the time dimension. Processes tend to be seen as islands of logic. The way in which people experience the service over a sustained period of time is often not explicitly modelled; nor is the way that the experience evolves. Too often, the result of this is frustration and inefficiency when the system turns out not to support the sequence of events that unfolds over the course of time.

A user-centred approach puts this right. UX methods use the power of narrative to understand and communicate the way that people really experience things. The time dimension is the final key conceptual element of UX in addition to those shown in Figure 2.2, which shows a snapshot of the situation at one particular moment in time.

Aesthetics and affect

Sometimes people think that UX is about creating attractive visual interfaces. This is basically incorrect. As the rest of this book will make clear, UX is primarily about understanding users and their needs, and designing to make sure that those needs are met.

However, that does not mean aesthetic considerations are insignificant. Arguably, they are important for their own sake; but also there is a considerable body of evidence supporting the view that aesthetically pleasing user interfaces are more usable than others. Self-evidently, a good-looking interface will result in a better user experience. People react more positively to attractive interfaces. This puts them in a frame of mind where they are more prepared to persevere with finding out how to accomplish a task that might not be self-explanatory. Human-centred design takes this into account.

Psychologists distinguish between two different aspects of our interaction with the world: cognition and affect. Cognition concerns the largely rational process by which we perceive, process and store information. Affect is to do with our emotions and feelings. Conventionally, the design of business systems is largely concerned with supporting cognitive processes in an optimal way. We need to take affect into account as well, most particularly when designing consumer products. This can only be done effectively by including UX design from the start of the process.

While the principles of user experience are often associated with the design of standalone products such as software apps and websites, they ‘scale up’ to the design of services and other socio-technical systems.

User experience emerges from the interaction of one or more users with a product or service. It consists of the users’ perceptions of, and responses to, the interaction. It both affects and is affected by the users’ goals and predispositions. It is strongly influenced by the physical and social environment of the users.

The term ‘user experience’ is used in a wide variety of ways. The concerns and techniques of the UX discipline are superficially similar to those of marketing and customer experience, but the mindset is very different. The respective primary concerns of UX specialists and business analysts are user needs and business needs, but each must also understand the other perspective.

Human-centred design prioritises usability over features or functionality. Rather than trusting in the expertise of specialists to build abstract models, it is based on understanding and valuing the subjective experience of users. Key aspects of this are user emotional responses and the time dimension.

REFERENCES

Cooper, A., Reimann, R., Cronin, D. and Noessel, C. (2014) About Face: The Essentials of Interaction Design. Wiley, Indianapolis, IN.

Cutting Edge, Graham Taylor: The Impossible Job (1994) [TV programme] Channel 4.

de Voil, N. (2013) People-oriented approaches. In Pullan, P. and Archer, J. (eds), Business Analysis and Leadership: Influencing Change. Kogan Page, London. Available from: https://www.koganpage.com/download?id=521

Garrett, J.J. (2010) The Elements of User Experience: User-Centered Design for the Web and Beyond. Pearson Education, San Francisco, CA.

Goodwin, K. (2011) Designing for the Digital Age: How to Create Human-Centered Products and Services. Wiley, Indianapolis, IN.

ISO 9241-11:2018 (2018) Ergonomics of Human-System Interaction – Part 11: Usability: Definitions and Concepts. International Organization for Standardization (ISO), Geneva.

ISO 9241-210:2019 (2019) Ergonomics of Human–System Interaction – Part 210: Human-Centred Design for Interactive Systems. International Organization for Standardization (ISO), Geneva.

ISO/IEC 25010:2011 (2011) Systems and Software Engineering – Systems and Software Quality Requirements and Evaluation (SQuaRE) – System and Software Quality Models. International Organization for Standardization (ISO), Geneva.

ISO/IEC/IEEE 15288:2015 (2015) Systems and Software Engineering – System Life Cycle Processes. International Organization for Standardization (ISO), Geneva.

Nielsen Norman Group (no date) The Definition of User Experience. Available from: https://www.nngroup.com/articles/definition-user-experience/

Norman, D.A. (2005) Human-centered design considered harmful. interactions, 12(4), 14–19.

FURTHER READING

Downe, L. (2019) Good Services: How to Design Services that Work. BIS Publishers, Amsterdam.

Norman, D.A. (2004) Emotional Design: Why We Love (or Hate) Everyday Things. Basic Civitas Books, New York.

Travis, D. (2007) A Business Case for Usability. Available from: https://www.userfocus.co.uk/articles/usabilitybenefits.html