Non-academic and academic social networking sites for online scholarly communities

Abstract:

This chapter discusses various social networking sites and tools that can be used to support and advance a variety of scholarly activities. It is divided into two main sections: (1) popular non-academic social networking sites; and (2) popular and emerging academic social networking sites for online scholarly communities. Each section includes analysis and discussion about the relative strengths and weaknesses of different social networking platforms, their target audience and community norms. The chapter concludes with a discussion on how to decide what social networking sites (academic or non-academic) are the best for academics and for what purposes. After working through the chapter, readers will understand the purpose and functionality of various social media and social networking sites and tools, as well as how they can be used to create and support online scholarly communities.

Introduction

Since the start of the Internet, communities of scholars have relied on more traditional computer-mediated communication (CMC) tools such as email and mailing lists to communicate and facilitate collaboration. With the recent advent of social media and social networking sites, scholars are now making the transition to these more versatile and interactive platforms to support their scholarly activities (CIBER, 2010; Gruzd, Staves and Wilk, 2011; Procter et al., 2010). In addition to being able to participate in informal peer-review processes, other frequently cited benefits associated with the scholarly use of social media and networking sites include their ability to:

1. help scholars find and establish new connections;

2. strengthen and maintain existing connections;

3. keep up to date with the latest research in their research community; and

This chapter will focus on these and other benefits with a special focus on how social media and networking sites can help to foster and strengthen online scholarly communities. The chapter will discuss some popular and up-and-coming general social networking sites that are being adopted by scholars for professional purposes, explore social networking sites and collaboration tools specifically geared towards academics, and conclude with a comparison between both types.

General public platforms for online scholarly communities

With the popularity of online social networking skyrocketing in early 2000 and the lack of sites designed specifically for academic communities, some scholars have turned to mainstream sites such as Facebook and Twitter to connect professionally and personally with their colleagues from around the globe. For example, a recent online survey conducted by Gruzd, Goertzen and Mai (2011) showed that 85 per cent (n= 367) of respondents, mainly North American and European researchers in social sciences, use non-academic social networking sites monthly or more frequently, versus 51 per cent who use academic social networking sites. The two most frequently used non-academic social networking sites that scholars use are Facebook and Twitter.

Facebook (http://facebook.com) is currently the leading social networking site in the world with 800 million active users as of October 2011 (Facebook, 2011). As a result, it is not surprising that there are some scholars mixed in among the avid users of Facebook. However, some of the scholars who do use Facebook for professional purposes find it extremely difficult to separate their personal and professional lives and are wary about what they perceive as a loss of personal privacy; see Chapter 10 in this volume for more about privacy concerns. The inability to separate and control various information silos on Facebook has forced some scholarly users to create multiple profiles on Facebook in order to regain a semblance of control over their various online identities (e.g., professional versus informal). And in a few extreme cases, some have even made the decision to withdraw from Facebook completely (see Gruzd, Staves and Wilk, 2011; Mendez et al., 2009). Nevertheless, the majority of academics who are using social networking sites still rely on Facebook to support their scholarly communication.

Twitter (http://twitter.com), a microblogging site for exchanging messages under 140 characters long, is another example of a general purpose social networking site that some scholars have embraced as a medium to establish and maintain their professional online communities. For instance, in a survey of 61 Semantic Web scholars (primary European), 92 per cent of respondents had a Twitter account that they used for academic purposes (Letierce et al., 2010). Twitter’s simple interface, real-time connections and its ability to form one-way connections (in which one person can subscribe to another user’s updates) creates an effective environment for dissemination of scholarly news and updates. It also creates an informal atmosphere in which two strangers who work in similar areas are now able to easily find and connect to each other via this site. Twitter is commonly used during academic conferences as a service to elicit instant feedback and chat among conference attendees (Young, 2009). But the question still remains: can a semi-anonymous social networking site for exchanging short messages such as Twitter foster and sustain a scholarly online community? Interestingly, early evidence indicates that it might.

A recent study by Gruzd, Wellman and Takhteyev (2011) attempted to answer this very question of whether Twitter can be used by scholars to create a sense of community, a key factor in establishing a successful online community. The study examined the use of Twitter by a networked researcher and scholar, Barry Wellman, who also happens to be a very active Twitter user with a relatively large follower base. The study examined the following three theoretical constructs that have proven to be necessary to support a lively online community, namely Anderson’s Imagined Communities, Jones’ Virtual Settlement, and McMillan and Chavis’ Sense of Community theories. The study confirmed that Twitter is capable of sustaining and fostering various interconnecting communities of scholars. Specifically, it found that Twitter is a common public place where scholars can meet and interact with one another, maintain the awareness of other community members through others’ messages, and experience the feelings of belonging and influence over one’s online community by forwarding others’ messages, and getting help with questions from other online users. One of the key discoveries of this work is that while there was indeed a core group of more closely connected users within Barry Wellman’s Twitter network who held the community together, it was still possible and relatively easy for newcomers to feel welcome and to create connections to members in the core.

One of the challenges of being on Twitter and other social media sites lies in handling an endless stream of information that comes from a multitude of sources. This often leads to information overload and eventually a desire to tune out. This is especially challenging on Twitter where many users follow on average anywhere from 100 people to 400 people (if those with over 500 followers are included) (Takhteyev et al., 2012). As social networking sites such as Twitter gain more acceptance among scholarly users, there are a lot of concerns over how users can deal with the inevitable information overload and how to differentiate conversations among various online communities. Chapter 6 of this book discusses many aspects of Twitter in greater detail. Here, I present one tool that addresses the above concerns of scholars, called AcademiaMap.com, which is in development at the Social Media Lab of Dalhousie University.

AcademiaMap

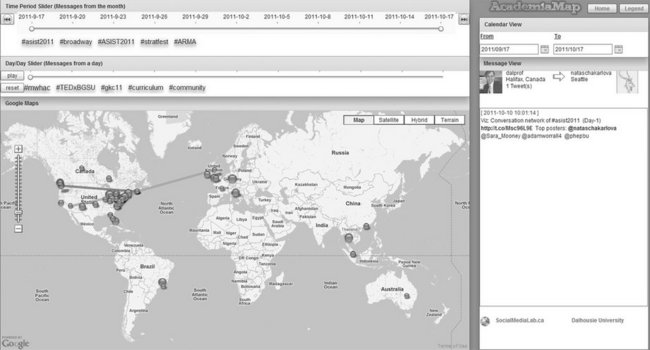

AcademiaMap (http://AcademiaMap.com) is an online Geographic Information Visualization (GIV) system that tracks Twitter conversations (in real time) and visualizes communication connections between scholarly users of Twitter from across the globe. The main interface of the system is shown in Figure 2.1. The tool is designed to help scholars filter the noise from their Twitter stream and allow more popular and potentially more relevant conversations within their scholarly community to be brought to the forefront. The infrastructure of AcademiaMap is designed to track the conversations of any scholarly community found within Twitter. The current beta version of AcademiaMap only tracks the public tweets of scholars who have been followed by the Twitter account @asist2011, which belongs to the American Society for Information Science and Technology (ASIS&T).

The interface is divided into three main areas: (1) the map, which shows where community members come from geographically; (2) the two sliders that control the date range for Twitter messages; and (3) the conversation pane to the right that shows profile information and messages posted by a selected individual or between any two people in the community. For a selected date period, the interface also displays the top five most popular topics (hashtags) posted by the community members. Clicking on any of these hashtags will bring up a list of messages in the conversation pane that mentioned this hashtag. In addition to showing topics that are popular in this community, the tool also shows its most engaged members and how these members are connected to other members of this scholarly community. For example, if one person mentioned another person in his or her message, there will be a line connecting these two individuals. Clicking on this line will show only the messages posted from the original user that mentioned the connecting user. Because of the way this tool is designed, it allows scholars to identify popular topics and voices among their Twitter peer group during a specific time period of their choice. It can also help its users increase their awareness of the community conversations without necessarily having to read the hundreds of messages posted daily. Finally, it can help its users identify new contacts within this community to pursue potential collaborative projects with colleagues in the future, or to follow their messages on Twitter.

Google +

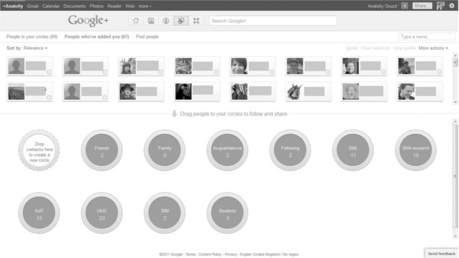

The final social networking site for the general public that will be discussed in this chapter is Google + (http://plus.google.com). Released in summer 2011, the site has already captured the attention of over 40 million users, according to one estimate (Allen, 2011). Not surprisingly, many researchers are found among this group of early adopters of Google +. Many of the scholars seem to be interested in exploring the possibility of using the site for their professional purposes. Just anecdotally, out of about 70 people who initially found and added me to their Google + profiles, all of them are professional, academic contacts (students, collaborators and colleagues in the same or related research areas). As a result, conversations that appear in my profile on Google + are primarily academic. Depending on how Google chooses to develop Google +, it has the potential to address many of the concerns over privacy that some scholars have expressed with regards to Facebook and might eventually become a hub for scholarly communities. One of the selling points of Google + for academics is that the site incorporates many of the useful features found in both Facebook and Twitter. For example, like Twitter, Google + supports asymmetric relationships where one user can follow another but the second user does not have to follow the first one back. As in the case with Twitter, such asymmetric relationships make it easier for one researcher to initiate contact with another researcher without having shared any previous work history together. This is because there is no expectation that the person whom you decide to follow has to also follow you back. At the same time, similar to Facebook, Google + allows its users to organize people in their personal networks into groups, or what Google calls ‘circles’ (see Figure 2.2), which makes it easier to share information with, and receive information from, only relevant groups of online followers (e.g., friends, family or colleagues). But what might give Google + an edge over competing general purpose social networking sites such as Facebook is the fact that Google already offers an entire suite of free, web-based collaborative productivity tools that are well suited for scholarly work such as Google Docs for research collaboration, and Google Chat for synchronous communication among remotely distributed teams; see Chapter 3 for more about technologies that facilitate collaboration. It is likely that over time, Google + will also offer an even tighter integration among all of its various online properties, making Google + the default social networking site for scholars. However, as at the time of this writing, it is still too early to declare Google + a winner or even a contender in the general social networking space or as a niche scholarly social networking space.

Academic sites for online scholarly communities

The previous section outlined some of the popular and trending social networking sites for the general public that have been adopted by scholars for professional uses. However, as noted earlier, these sites raise some privacy concerns and do not have all of the features that make them ideal for use in a scholarly and professional setting. For example, Facebook makes it very easy for its users to share photos with friends; this is a very popular activity, especially among younger users. However, scholars are more likely to be interested in sharing articles and comments about articles than photos. But Facebook does not offer features that would enable sharing of peer-reviewed articles (including the full citation data such as article title, authors, year of publication, journal title, etc.) with other users. Due to these hindering concerns and limitations associated with the mainstream sites, over the last few years a few niche social networking sites specifically aimed at scholars have been launched. In this chapter, only the two fastest growing scholarly sites, ResearchGate. net and Academia.edu, will be discussed. Sites such as Mendeley and Zotero, which have social networking features but primarily focus on the collection and dissemination of bibliographic records, are discussed in Chapter 5.

ResearchGate.net

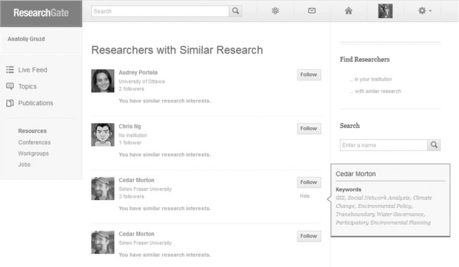

Launched in 2008, ResearchGate (http://ResearchGate.net) had over 1 million users as of 1 December 2011. Most of its current users are researchers from medicine and biology (over 200,000 members in each discipline), followed by researchers in engineering, chemistry, computer science and agricultural science (with ~ 70,000–98,000 members each). Users from other disciplines are also present on the site, but they are few and far between.

From a user interface perspective, ResearchGate includes many of the popular features and functionalities that are now common among current social networking sites such as creating unique user profiles, posting public and private messages, sharing information, and finding other users with similar interests. However, since this site is designed with academics in mind, it contains many features that allow and encourage its user base to connect and converse around research interests and publications. The registration process is easy; once registered, users are required to: (1) enter their research interests in the form of keywords; (2) select one or more research fields; and (3) add publications. Publications can be added by uploading from popular reference managers such as EndNote, by searching publications in databases such as PubMed, IEEE or CiteSeer, or by adding them manually.

One of the useful features of the site is that it can recommend relevant articles and other researchers in the same area just based on the research interests that a user entered (see Figure 2.3). The recommended articles can also be rated and shared with others.

ResearchGate also has a built-in blogging feature that enables users to write a ‘microarticle’ (a short review of a published peer-reviewed paper) or a ‘post’ on a general topic, such as a recent conference trip. Users can also submit their blog posts to be featured on ResearchGate’s main blog where the post will likely get a larger audience. This is a useful and easy-to-use feature. Unfortunately, ResearchGate does not currently offer an automated way for users who already maintain their own blogs elsewhere to cross-post from their external blogs.

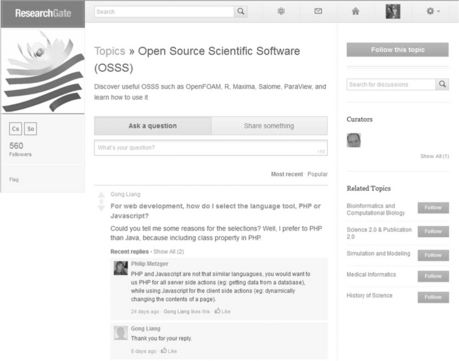

In addition to being able to follow other users, ResearchGate also allows its users to follow research topics. For example, Figure 2.4 shows a page about Open Source Scientific Software (OSSS). The stated purpose of this page is to help users ‘discover useful OSSS such as OpenFOAM, R, Maxima, Salome, ParaView, and learn how to use it’ (Velten, 2011, para. 1). As of November 2011, it had 834 followers. What makes this page interesting and useful to its users is the fact that it is set up like an online forum where users can post and reply to each other’s questions. Some other features worth mentioning here are the ability to create a ‘workgroup’ as well as an invitation-only space to collaborate with colleagues, create polls and share files.

Academia.edu

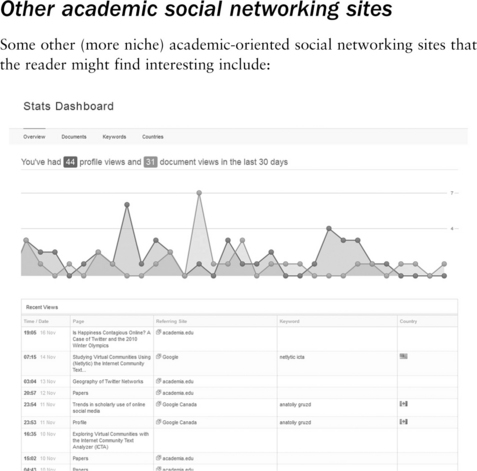

Another popular academic social networking site, also launched in 2008, is Academia.edu. It has over 800,000 members, primarily in the social sciences. Academia.edu has many of the features found in ResearchGate such as maintaining a list of one’s publications, following topics or researchers with similar research interests and publishing blog posts (see Figure 2.5). However, Academia.edu also has a set of unique features that distinguish it from other scholarly social networking sites. First, the site allows its users to add sections to their profiles such as a CV, teaching documents and talks. The site also has the ability to automatically re-post updates to Facebook, a useful feature for academics who maintain their presence on more than one social networking site. Another unique feature of Academia.edu is that it provides its users with information on how many people visited their profile, from what countries and what they found interesting on the user profile (see Figure 2.6). Such analytics offer valuable insights to scholars about the popularity of their research and its geographic reach. They can give users a rough indication as to what papers might get more citations in the future, which in turn may inspire a scholar to pursue and expand a certain line of research.

Other academic social networking sites

Some other (more niche) academic-oriented social networking sites that the reader might find interesting include:

![]() MethodSpace.com, which focuses on methods for qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods research, run by the publisher, Sage.

MethodSpace.com, which focuses on methods for qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods research, run by the publisher, Sage.

The review of these and other social networking solutions for scholars can be found on the Social Media Lab blog at http://SocialMediaLab.ca.

The sites listed above are all public sites and are accessible by any researcher in the world. But sometimes a research group or an institution needs to set up a private social networking solution just for its members. Such solutions can be a simple blog for a research group using an open source platform like WordPress, or a wiki using the popular MediaWiki software. But it can also include a more complex solution for social networking and collaboration such as HUBzero (https://hubzero.org), developed in conjunction with the Network for Computational Nanotechnology or VIVO (http://vivoweb.org). The first solution, based on a blogging or a wiki platform, is especially useful for smaller research labs and can be effectively used to coordinate the lab’s work as well as build a sense of community among lab members. The last two solutions, HUBzero and VIVO, are especially useful for the discovery of experts and potential collaborators based on users’ research interests within a larger unit such as an academic department or a university.

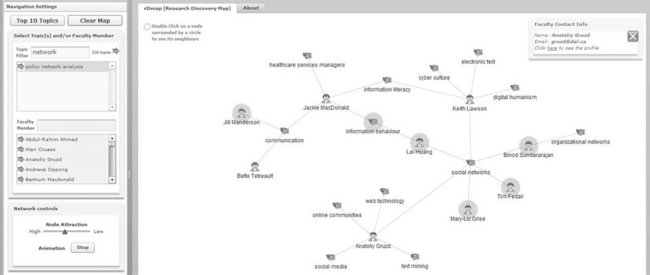

Other similar platforms in this area include KnowledgeNetwork, being developed at the University of British Columbia (http://knowledgenetwork.ubc.ca), and the rDmap (Research Discovery Map) application, currently being developed at the Social Media Lab at Dalhousie University. Both applications attempt to visualize existing and potential research connections among university researchers. For example, rDmap connects faculty members to their research topics and their peers within their university. This helps faculty members to quickly and easily identify potential collaborators, while allowing students to find potential supervisors for their thesis work or reading courses (see Figure 2.7). A sample installation of rDmap for Dalhousie University Faculty of Management is available at http://iresearch.management.dal.ca/fommap.

The primary advantage of such custom solutions is that an institution is in control of the content and customization of the site, but the limitation is that it requires the installation and maintenance of special software.

Conclusions

With so many different social networking sites available to network and share information with peers, which one should you choose? Should you go with a general purpose non-academic site or maybe start a profile on an academic-specific site? One way to answer this question is to ask your local and distant peers in your field what social networking site(s) they are using and then create the profile(s) accordingly. This is because your offline peers will likely be your online ‘followers’ as well. However, be aware that by going down this route, you might be unknowingly excluding some other groups of researchers and professionals in other fields who might also be interested in your work since they may be using a different social networking site. So we are back to the initial question: what site do you choose if you are new to online social networking?

Both non-academic and academic social networking sites discussed in this chapter offer many similar features and benefits to their users such as the ability to: make new research contacts; promote current research; follow other researchers’ work; and keep up-to-date with current topics in your field. However, there are also some clear differences between them. The positive side of non-academic platforms is that they potentially have a larger user base due to their early start and general appeal. But because of their general appeal, it might be difficult for a scholarly user to separate personal from professional contacts and avoid potentially embarrassing and sometimes career-ending situations. As one participant from the study discussed in Gruzd, Staves and Wilk (2011) stated, ‘Managing and negotiating the always changing privacy settings of Facebook is an ongoing task for me.’ On the other hand, academic-specific platforms such as ResearchGate.net and Academia.edu are free of these types of worries, since their users are less likely to find their personal contacts on those sites. But the drawback is that they do not have nearly as many users as Facebook, Twitter or Google +. As a result, many researchers still doubt whether spending time building a professional online identity on academic-only sites will pay off professionally in the long run.

One possible solution to the conundrum outlined above is to maintain multiple accounts on both academic and non-academic social networking sites. The drawback is obvious; it is already time-consuming to manage one online account, not to mention two or three. But the advantage is that it will be easier to reach various overlapping and non-overlapping online communities of scholars and professionals. If you do decide to follow this advice, instead of simply duplicating material on multiple sites, try to identify who follows you on different sites and then customize your messages and content to match different online communities (e.g., scholars in your field, scholars in other fields, professionals, students, media, etc.) Also, try to write goals that you might want to achieve via different networking sites. For example, I reserve Facebook for communication with friends and close collaborators in academia (socializing and awareness maintenance purposes), and Twitter for gathering and disseminating research-related news, publications and events to academic peers and other professionals. I use Academia.edu to maintain an up-to-date list of my publications, which makes it easier for other researchers to discover and cite them, and also to find related others’ papers. And finally, I use LinkedIn, a social networking website for career-related networking, to stay in touch with current and former students and to maintain contacts with industry partners. Furthermore, to help manage these multiple profiles, I often rely on software tools such as TweetDeck (http://www.tweetdeck.com) and Hootsuite (http://hootsuite.com) to follow and cross-post messages to multiple online social networks at once (when it is appropriate).

In summary, there is currently no one-stop solution that will satisfy all of the social networking needs of scholars, and it looks like it might take some time for a clear leader to emerge, if at all. In the meantime, to be an effective online networker in the age of social media, scholars will, for the time being, need to maintain multiple social networking accounts. This can be very daunting for any scholar, since doing so will require a certain level of time commitment. But this effort does often have very tangible pay-offs in the form of new professional and media contacts as well as an increase in the visibility and reach of one’s research initiatives. As one scholar in the Gruzd, Staves and Wilk (ibid.) study noted, it is also time-consuming to go to conferences, but we still do it.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (SSHRC) and NCE Graphics, Animation and New meDia (GRAND) grants. I would like to thank Philip Mai and Kathleen Staves, members of the Social Media Lab at Dalhousie University, for their help and feedback during the preparation of this chapter.

References

Allen, P., Google + is really taking off! Millions joining daily [Google + public post]. 2011, 22 September. Retrieved from. https://plus.google.com/117388252776312694644/posts/K9Qf1UVNyGy

CIBER, Social media and research workflow [report]. 2010. Retrieved from. http://www.ucl.ac.uk/infostudies/research/ciber/social-media-report.pdf

Facebook, Statistics. 2011. Retrieved from. http://facebook.com/press/info.php?statistics

Gruzd, A., Goertzen, M., Mai, P., Survey results highlights: trends in scholarly communication and knowledge dissemination in the age of social media [report]. 2011. Retrieved from. http://socialmedialab.ca/?p=4308

Gruzd, A., Staves, K., Wilk, A., Tenure and promotion in the age of online social media. Grove, A., ed. Proceedings of the ASIS&T 2011 Annual Meeting. Silver Spring, MD: American Society for Information Science and Technology, 2011.

Gruzd, A., Wellman, B., Takhteyev, Y., Imagining Twitter as an imagined community. American Behavioral Scientist. 2011;55(10):1294–1318, doi: 10.1177/0002764211409378.

Letierce, J., Passant, A., Breslin, J.G., Decker, S., Using Twitter during an academic conference: the #iswc2009 use-case. Hearst, M.A., Cohen, W., Gosling, S., ed. Proceedings of the Fourth International AAAI Conference on Weblogs and Social Media. National University of Ireland, Galway, 2010:279–282.

Mendez, J.P., Curry, J., Mwavita, M., Kennedy, K., Weinland, K., et al, To friend or not to friend: academic interaction on Facebook. International Journal of Instructional Technology and Distance Learning. 2009;6(9). Retrieved from. http://www.itdl.org/Journal/Sep_09/article03.htm

Procter, R., Williams, R., James, S., Poschen, M., Snee, H., et al. Adoption and use of Web 2.0 in scholarly communications. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences. 2010; 368(1926):4039–4056.

Takhteyev, Y., Gruzd, A., Wellman, B., Geography of Twitter networks. Social Networks. Special Issue on Space and Networks. 2012;34(1):73–81, doi: 10.1016/j.socnet.2011.05.006.

Velten, K., Open Source Scientific Software (OSSS). 2011. Retrieved from. http://www.researchgate.net/topic/Open_Source_Scientific_Software_OSSS/

Young, J. 10 high fliers on Twitter. The Chronicle of Higher Education. 2009; 55:A10.