When good research goes viral! Getting your work noticed online

Abstract

It is possible to use many online outlets to make your research go viral, or popular with many people online. This chapter provides an overview of how to do this. You can use social media tools such as blogs, Facebook, Twitter, Google +, and YouTube for promoting and providing your research to your academic community. Additionally, this chapter explains how you can influence Google search results to your benefit with techniques such as search engine optimization, and why you should care about search result rankings. Other pointers include using your Google Scholar Citations profile as well as your university’s existing Internet infrastructure to prominently position your research online.

Introduction

Many of us academics have a research component in our job descriptions. I work at a research-intensive university; on paper, research is a full 40 per cent of my job, and research really counts more for tenure and promotion decisions than does teaching. Clearly, it is important for me to win grants, hire capable research assistants and publish in peer-reviewed journals. Equally, or more, important is the task of getting my research noticed by my academic peers. Today’s journals (and, increasingly, books) are mostly only accessed online but this can work to our disadvantage. In today’s digital environment, we are constantly inundated by more and more online information. The relatively level playing field of online information access means that we compete for our colleagues’ online attention alongside every other researcher in our field (not to mention photos of our friends’ children, clips from last night’s The Big Bang Theory, and so on). Certain tools are at our disposal to help us manage all the information, such as publishers’ table of contents email alerts when new journal issues are published online, but there is still no guarantee that our research will get noticed, read or cited because so many elements are working against us. Is there anything we can do? I’d like to suggest in this chapter that we can make our research go viral using both social and traditional tools.

What exactly does it mean when something ‘goes viral’? The idea has been present in business for some time now; essentially it means that you can make your customers do your marketing for you (Scott, 2010). The masses have the power to make online items popular by posting links to them on their Twitter or Facebook accounts, writing about them on their blogs, commenting on YouTube videos they like, emailing them to 200 of their closest friends (we all know people who do this!), and so on. We tend to follow people and organizations we know, trust and like online, which makes us likely to be interested in viewing content that friends or respected organizations recommend.

We have seen this play out in popular culture over the last few years in many contexts. YouTube videos are a good example. As early as 2006, the ‘Diet Coke and Mentos’ YouTube videos started garnering hits on YouTube, providing people with a quick laugh; see http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hKoB0MHVBvM if you’ve never seen this experiment. Regardless of what you might think about his singing abilities, popular music star, Justin Bieber, was discovered after videos of him singing and playing guitar were posted on YouTube and viewed by large numbers of teenage girls everywhere. The ‘Old Spice guy’ commercials went viral instantly in 2010, receiving over 50 million views in just a few months (Wiancko, 2010).

This model works well in business and popular culture, but how would we apply it to academic research? Are 50 million people going to care that a biologist made a new discovery about the eating habits of one frog species that lives in northern Manitoba? That’s not likely, unless this discovery can cure cancer, but we can use similar techniques to help our peers notice what we are doing. This chapter explores ways to do that.

Social networking: Facebook, Twitter, LinkedIn, YouTube, and so on

Using social networking to make our research go viral corresponds with Chapter 2, ‘Non-academic and academic social networking sites for online scholarly communities’. Since this brief chapter draws largely on my own practice and experience, I will be completely honest in stating that most of my viral self-marketing takes place on Facebook. Keeping in line with what Chapter 2 discusses, this is true for me simply because it’s where I connect with most of my colleagues. While I have friends, family and colleagues on my sole Facebook account, I tend to post mostly professional content on Facebook because it’s the least personal common denominator. (My family doesn’t always understand what I post, but my seemingly enigmatic posts provide good conversation fodder at holiday gatherings.)

Let us say that I get the fortunate news that a journal has accepted one of my articles. Since I have waited months for this decision in many cases, I’m obviously excited, and I want to share it with people I know. I post two words and a smiling emoticon as my Facebook status:

What happens when I do this? Unfailingly, a respectable number of my Facebook friends, mostly colleagues, ‘Like’ the status; it seems to be human nature (or Facebook nature) for us to appreciate positive status updates. Additionally, if I don’t give away too much information in the update, I get comments on the status, such as, ‘Congratulations! What’s the topic? What journal?’, which builds ‘buzz’ around the update.

After the article is published, I can take advantage of the online nature of today’s scholarly communication and post a link to the journal article in Facebook. Since I have worked hard to build a friendly and consistent – but not overpowering – presence on Facebook, people do seem to watch my links and updates even more than I necessarily realize. Often, a faculty colleague or doctoral student will see me in the hallway and say, ‘I saw your article on Facebook! It looks interesting! I’m looking forward to reading it.’ I don’t always get direct feedback about the work itself on Facebook but it gets noticed, which is all we can hope for sometimes. These Facebook tactics can work for not only journal articles but conference papers, monographs, exhibitions … whatever ‘research’ means in your field. I also post occasional observations, frustrations or successes I have in my research life. On the day I drafted parts of this chapter, I posted:

This comment prompted posts from a colleague about avoiding the telephone on a research day. The exchange wasn’t anything major but it put the idea that research is on my schedule into colleagues’ minds. It also builds rapport: we can all commiserate about how busy academic life is, and how hard it can be to find uninterrupted time for research.

Twitter is another social networking site you can use to promote your research. Twitter can be a complicated place for new initiates. Chapter 6 covers Twitter usage in great detail so I won’t discuss it too much here. I would like to say here, as Lynne Williams and Jackie Krause say in Chapter 6, that Twitter is more of a one-way communication tool than a two-way discussion tool. For this reason, as well as the fact that it just isn’t as well-populated with my colleagues as Facebook, I cannot say that I participate in Twitter very often. However, if you and your peers use (or want to use) Twitter you can use similar tactics on Twitter. Especially if you are fortunate enough to be a research leader in your discipline, it is possible to build a following if you post often. You can also take advantage of the relatively one-way nature of Twitter (again, that is my opinion) by posting not only announcements related to your productivity but thoughts about your research area, such as thoughts about a new article, your recent research questions, and so on. Since people go there to get news updates, there is no reason why academic researchers can’t share ideas there as well. Invite your closest colleagues to follow you, and see if your following grows as you continue to post thoughtful comments and announcements about your research productivity. Even if this doesn’t get conversation going, hopefully it will at least make people think about your comments.

Linkedln

As Anatoliy Gruzd notes in Chapter 2, LinkedIn is ‘a social networking website for career-related networking’. LinkedIn is a much more active site for private sector professionals than for academics, but it’s definitely worth having a presence there. LinkedIn allows account holders to provide their employment history, education and other CV-related details. LinkedIn members can make ‘connections’ with each other, which is similar in concept to ‘friending’ someone on Facebook.

LinkedIn excels with potential viral capabilities in its ability to recommend people for connections. There are some privacy concerns with LinkedIn, however; it may search your email address books and so on. It is unclear exactly how LinkedIn finds suggestions for connections. Recently, LinkedIn recommended connecting to a personal trainer I worked with about five years ago, and I’m not even sure we exchanged emails! Also, LinkedIn allows your connections to ‘recommend’ you by writing on your profile what they like about you as a professional colleague. When people find your profile, these connections might create some buzz about you. One more piece of potentially viral information LinkedIn provides is how many people have searched for you in the last month. This information in itself is not viral but it can give you a sense of how many people are looking for you – especially if you compare that number to how many people have added you as a connection in the past month.

YouTube

As illustrated by my earlier examples, YouTube videos can go viral for many reasons. It might be unreasonable to think that a video of you talking about the mice in your lab will garner 23 million views in a week but it is certainly possible to gain the attention of students and colleagues in your field.

The standard lecture or ‘talking head’ video format is prevalent. This has been used for many years in contexts such as distance education classes and it can certainly convey important messages. In some circumstances, these can go viral, especially if they get attention from non-academics. For example, the video at http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dBnniua6-oM, which features Dr Robert H. Lustig of the University of California, San Francisco, discussing the negative health impact of eating sugar, has had over 1.8 million views at the time of this writing. You can tell by reading the comments that many of the viewers have not been academics. If you want your research to reach an audience that exists outside of academia, it may be necessary to either: 1) change your research agenda, which would entail too much work; or 2) find an angle that makes your work interesting and relevant to the general public. (Think Carl Sagan.)

It is also possible to present work and ideas in a non-standard lecture format. Many people create instructional videos with software such as Camtasia, which records anything you do on the computer screen and your voice, so you can narrate as you demonstrate. This is an effective tool for online classroom demonstrations but it can be used for conference-style presentations or other demonstrations as well. The possibilities are limitless!

Once you’ve started creating YouTube content, or at least have a plan for content, consider creating a YouTube ‘channel’. YouTube users can ‘subscribe’ to channels that interest them, so they get updates when their favourite channels receive new content. Individuals and organizations create channels to hold and organize their YouTube content; a directory of these can be found at http://www.youtube.com/channels. Universities, too, create channels; for example, the University of California’s channel at http://www.youtube.com/user/UCtelevision contains a video of Dr Lustig’s lecture and many others. If your university or department has a channel, you should definitely consider contributing content. If not, create your own channel. The link to the channel should be listed in your email signature as well as your Facebook page/LinkedIn profile/Twitter account – whatever social media platforms you decide to utilize. As your social media profile becomes noticed, your YouTube channel will get known too.

Blogs

In Chapter 1, Carolyn Hank reviews academic blogging basics so I will avoid exploring details about blogging in this chapter and just discuss some promotional ideas. While blogs can be a wonderful way to get your research noticed, keep in mind that if your blog isn’t in your adoring public’s minds, it won’t get read. Just like your official publications, you can link to your blog on your Twitter, Facebook and LinkedIn profiles, and mention when a new post is available. Likewise, place links to your Twitter, Facebook and LinkedIn profiles on your blog. The blog I co-edit, ‘tl-dr.ca: where gamers and information collide’, is linked on the faculty profile page hosted by my university’s website and I do get blog readers referred from that profile page. Ensure that it is easy for people to follow your blog by using Really Simple Syndication (RSS) feed aggregators such as Google Reader. This involves placing a link to your RSS feed on your blog; WordPress themes will typically assist you with this via an RSS widget. This is very important to do because many people rely on RSS-based services to keep current with all their online news sources, and you want your blog to be one of those sources.

Google, you and ‘the filter bubble’

On today’s Internet, Google is the indisputable leader in providing our starting point to online content, and social media further directs us to online content. According to Alexa (2011), a company that provides web metrics, Google is the top website in the world, followed by social media sites Facebook and YouTube. ‘Googling’ a topic – even our own name – has become a household word. On social media, if we ask a question about something, other people sarcastically tell us to ‘just Google it’. My research into how young people find and evaluate online mental health information (Neal et al., 2011) has revealed, however, that although people typically start with a Google search, they do not always find the accurate, reliable information they want. Additionally, most people do not look beyond the first page of Google’s search results (McTavish et al., 2011). Therefore, as hard as we might work to make our research go viral, if Google doesn’t rank our work prominently when someone Googles our name or research area, it will be disadvantageous. As Bailyn (2011, back cover) wrote, ‘If you aren’t at or near the top of Google searches, you won’t be found.’ We must understand and plan against the factors affecting this phenomenon as much as possible.

Nobody really understands the mechanics behind how Google’s search result list ranking works except Google itself, but we do know a few things about it. Google’s ranking order, which is known in the information retrieval system terminology we use in my field of information science as ‘relevance ranking’, is based on something Google calls PageRank. When Google founders, Sergey Brin and Larry Page, started Google as graduate students at Stanford University, they built their search algorithm on the idea that the importance or relevance of web pages was based on how many other web pages link to it. So, the more web pages link to a site, the higher the Google PageRank (Bailyn, 2011; Langville and Meyer, 2006). Influences on PageRank’s evaluation of a website’s importance constantly evolve, and the influence of social media sites is an increasing factor: how many times a page is linked on Twitter, Facebook or Google +, for example.

Clearly, then, it is important to get as many sites to link to sites containing your research output as possible (and to link to them yourself on social media sites), but there are tactics around it as well. There is an entire industry called search engine optimization (SEO) that focuses on increasing websites’ search engine rankings. Understanding how to implement SEO for your sites is a little technical, but not insurmountable. For an introduction to SEO’s workings and implementation options, see one of many resources such as Bailyn (2011) or Tossell (2011).

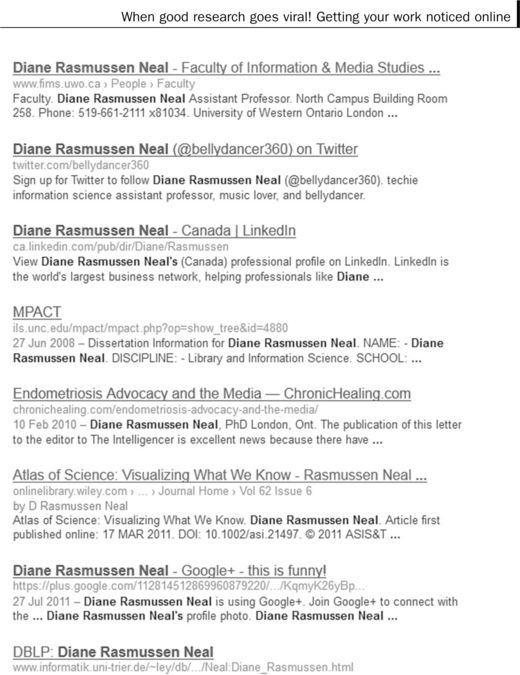

Another factor influencing people’s Google search results is what Eli Pariser (2011) calls ‘the filter bubble’. A video of Pariser’s talk about this concept is available at http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=B8ofWFx525s. Essentially, he points out that every individual’s Google results are personalized based on one’s computer, browser, geographic location, and so on. You do not have control over what he calls this ‘personal unique universe of information’. Based on this principle, the faculty member next door to you could do a search identical to yours and get different results than you because she is using a MacBook as opposed to your PC. I have seen this at play as well when I travel to different countries: I get google.ca results at home in Canada, google.com.au results in Australia, and so on, all with country-specific rankings. Somebody browsing the web with Google Chrome may get different results than an Internet Explorer user. This makes it difficult to predict exactly how Google’s search results for my name will appear on the first page of any one person’s ‘hit list’. To demonstrate this, Figure 9.1 displays the hits on my first page of results for ‘Diane Rasmussen Neal’ on google.ca in December 2011, using Windows 7 and Firefox.

The first result is my profile page on my university faculty’s official website. This is a very good result to have listed first; see the following section for more thoughts on this. The second and third results are my Twitter and LinkedIn profiles, respectively. Next is a discipline-specific website with information about my dissertation and associated ‘academic genealogy’ information. Surprisingly, the next result is a letter I wrote to an editor in a blog post written by my friend that referenced me; this makes me a little uncomfortable because while it is a discussion about chronic illness misinformation, I am not sure how much I want my colleagues to know that I suffer from this disease. Next is an invited book review I wrote for the Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology (JASIS&T). It is ‘only’ a book review, but I am very proud of it, since the editor really liked the review, and the book won the Society’s Information Science Book of the Year award in 2011. Next is a Google + post of little consequence, a citation database that attempts to link information scholars by shared publications, http://www.peekyou.com (one of those pesky ‘people search’ engines that does not represent anybody in a flattering way!), and a link to a site containing the presentations for a panel I sat on at the Annual Meeting of the American Society for Information Science and Technology in 2011. As this demonstrates, all these sites relate to me, and some of them are ‘social’ sites. None of my published peer-reviewed articles shows up, which is unfortunate. However, these results are better than what I would get if I searched Diane Rasmussen Neal without quotes, or just Diane Neal – in which case I get gossip pages about the Law & Order actress, Diane Neal! Feel free to Google my name from your computer and see what results you get.

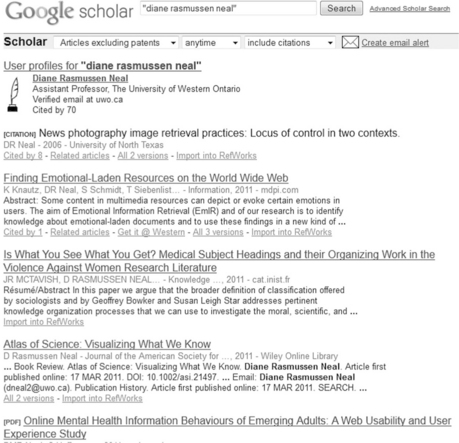

In Chapter 4, Maureen Henninger discusses Google Scholar (http://scholar.google.com) in some detail, including its ability to help you find other scholars’ papers of interest. Figure 9.2 shows a screen shot of the Google Scholar results for ‘Diane Rasmussen Neal’ (again, in quotes).

I find Google Scholar to be quite accurate in its results for scholars’ names, and extremely accurate for paper titles. For this reason, it’s important to make sure that your Google Scholar Citations profile is up-to-date.

To learn more about Google Scholar Citations, seehttp://googlescholar.blogspot.com/2011/11/google-scholar-citations-open-to-all.html. Based on the connections Google Scholar made for my Google Scholar Citations profile, it was excellent at determining which ‘Diane Neal’ needed to be linked to me. I should know better as a librarian but I have published under different versions of my name (Diane Rasmussen Neal, Diane M. Neal, Diane Neal, etc.), which makes my citation counts look lower than they are. This is one pitfall to avoid, whether you get married and use your husband’s last name or just cannot decide if you like your middle initial.

Official university pages: viral is not always better

Despite the shiny newness of social media, there are still some ‘old school’ web outlets that rank prominently in Google’s hits. University websites are one such example. Since we have a content management system (CMS) in my faculty and I am allowed to edit my page, I keep the page very current with lists of upcoming and recent publications as well as brief teaching and service descriptions. As previously mentioned, I also link to the blog I co-moderate, ‘tl-dr.ca’, on this page. I want to note here that it is very important to keep your faculty profile page as current and up-to-date as possible! Simply because that page is tied to the university website as a whole it will probably receive higher search rankings than almost anything you create yourself, because the domain name has been in existence for years and receives frequent hits from many stakeholders. If you create your own website (such as DianeRasmussenNeal.ca, for example) it will be difficult to receive higher search engine rankings because the site is not part of that larger infrastructure. Blame PageRank. Not every academic department is fortunate enough to have a CMS, but if it is possible to at least ask your local web contact to link to some publications on a perfunctory faculty profile page for you, you will notice a difference in how many people read and cite your research.

Another option for promoting your research within your university’s existing online infrastructure might be its ‘institutional repository’ (IR). In this model, the university library provides an option for researchers to place electronic copies of published work on a university server and people can access your work there for free. There are licensing issues to be worked out with certain publishers, especially if it is the type of publication in which you must relinquish copyright, but these details can be worked out. When copies of your work are available in an IR, people can find all your work (not just journal articles but other forms of literature such as presentation slides, conference abstracts, etc.) in one place. You can see my university’s IR, called Scholarship@Western, at http://ir.lib.uwo.ca/. If you are not sure whether your university has an IR, ask the library. IRs are an emerging mode of providing scholarship; faculty have legitimate reasons to avoid placing their work in them (Brown and Abbas, 2010). However, if we all agree to work through the challenges and start using them we can work through the issues collectively. If it becomes easier for people to access and cite our work because of increased IR activity we can only benefit from this service.

Conclusions

As I conclude this chapter, the question arises: How viral do you want to be? Lynne Williams demonstrates in Chapter 10 how all your online ‘yous’ can blur, and unless you go off the grid you may not be able to avoid this completely. One suggestion is to employ different usernames. If you are BioDoctor65 on your professional YouTube videos, you might want to be HotMama99 when you post YouTube videos of you and your dogs playing in the park. Your academic circle does not need to know that you dress your chihuahua in purple sweaters, but that’s something I do!

Also, it is important to use only the viral outlets that appeal to you. For example, if you find that Twitter’s constant update stream is too busy for your tastes, consider spending more time on building your LinkedIn presence or just link your papers on your university faculty profile. Conversely, if you find it helpful to tweet ideas as you think and write you are likely to gain followers. Whatever you choose, make sure that: 1) it fits with your personality; and 2) you do it consistently and thoroughly. Nothing reflects worse on your online, professional, viral self than a lingering Twitter profile that you have not touched for over a year – especially if it is the first hit in a Google search for your name! Perhaps the most important thing we can do is to make sure that only the things you want colleagues to find online, are online … and nothing else.

References

Alexa, Top sites. 2011. Retrieved from. http://www.alexa.com/topsites

Bailyn, E. Outsmarting Google. SEO Secrets to Winning New Business. 2011. [Indianapolis, IN: Que].

Brown, C., Abbas, J.M. Institutional digital repositories for science and technology: a view from the laboratory. Journal of Library Administration. 2010; 50(3):181–215.

Langville, A.N., Meyer, C.D. Google’s PageRank and Beyond: The Science of Search Engine Rankings. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press; 2006.

McTavish, J., Harris, R., Wathen, N. Searching for health: the topography of the first page. Ethics and Information Technology. 2011; 13(3):227–240.

Neal, D.M., Campbell, A.J., Williams, L., Liu, Y., Nussbaumer, D. ’I did not realize so many options are available’: cognitive authority, emerging adults, and e-mental health. Library & Information Science Research. 2011; 33(1):25–33.

Pariser, E. The Filter Bubble: What the Internet is Hiding From You. New York: Penguin Press; 2011.

Scott, D.M. The New Rules of Marketing and PR: How to Use Social Media, Blogs, News Releases, Online Video, and Viral Marketing to Reach Buyers Directly. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons; 2010.

Tossell, I., Handle SEO with care Retrieved from. 2011. http://www.theglobeandmail.com/report-on-business/small-business/digital/web-strategy/handle-seo-with-care/article2015296/

Wianko, R., And the ‘Oldspice Maneuver’ is created, blows the doors off of advertising [blog post] Retrieved from. 2010. http://ryanwiancko.com/2010/07/15/and-the-oldspice-maneuver-is-created-blows-the-doors-off-of-advertising/