Discourse Function Ambiguity of Fragments: A Linguistic Puzzle

Abstract: The puzzle we consider in this paper is that Merchant (2004) judges certain elliptical utterances in context to be ungrammatical, while Culicover and Jackendoff (2005) judge similar examples to be grammatical. The main difference between the examples appears to be that Merchant’s are introduced by no, while Culicover and Jackendoff’s are introduced by yes. We propose that the different judgments do not reflect grammaticality, but complexity associated with ambiguity. First, there is an ambiguity with respect to the reference of noun phrases in discourse: the relationship of the fragment to the preceding discourse is ambiguous. Second, there is an ambiguity with respect to the discourse function of an utterance, and in particular, whether it is an affirmation triggered by yes or a denial triggered by no. In the case of the denial, it needs to be established, which part of the preceding statement has to be corrected, while in the case of the affirmation, no such ambiguity arises. The interactions between these two interpretive functions may under certain circumstances render particular sentences in discourse difficult to interpret. Interpretive difficulty has the subjective flavor of ‘ungrammaticality’; in the case that we discuss here, these judgments form the basis for a particular linguistic analysis. But, we argue, manipulation of the discourse context can simplify discourse interpretation by resolving the ambiguity, which removes the interpretive difficulty. The conclusion that we draw is that the phenomenon in question is not a matter of linguistic structure, but of discourse interpretation.

1 The Puzzle

We consider here a puzzle that turns on dialogues such as (1) and (2), which show bare argument ellipsis (BAE) in B’s response. Surprisingly, (1B) is ungrammatical in its dialogue, while (2B) is grammatical, but they appear to have exactly the same syntactic structure and the same relationship to their respective antecedents.

(1)

- A: Does Abby speak the same Balkan language that Ben speaks?

- B: *No, Charlie.

(Merchant 2004, 688)

- A: John met a guy who speaks a very unusual language.

- B: Yes, Albanian.

(Culicover & Jackendoff 2005, 245)

Merchant’s argument for the presence of invisible structure is based on the observation that the DP which Charlie is associated with, that is, Ben in (1A), is inside of a relative clause. On Merchant’s account, the derivation of the fragment Charlie involves two steps: The first step involves extraction from the interior of the sentence (indicated by the crossed out Charlie), as in (3).

The second step involves deletion of the rest of the sentence on the basis of identity with the antecedent structure, as indicated by the crossed out Abby speaks the same Balkan language that Charlie speaks in (4).

(4) *No, Charlie ![]()

The derivation is graphically represented as in (5) (based on Merchant 2004):

(5) a. No, Charlie ![]()

On this analysis, the derivation involves a violation of the Complex NP Constraint (Ross 1967) or a comparable constraint, known as Subjacency (Chomsky 1973). Since (3) violates this constraint and (4) is derived from (3) (arguably by deletion of phonological material only), it comes as no surprise that (1B) (=(4)) is ungrammatical.

Since extraction from a relative clause is in general ungrammatical in English, Merchant (2004) takes the ill-formedness of (1B) to be evidence that supports the extraction/deletion analysis. Furthermore, in example (6), Merchant shows that the response is grammatical if the complete response without extraction and deletion is provided as an answer to the question, as Krifka’s (2006) association with focus theory predicts (see also Drubig 1994).

- A: Does Abby speak the same Balkan language that Ben speaks?

- B: No, she speaks the same Balkan language that Charlie speaks.

On the other hand, Culicover & Jackendoff (2005) judge A′-extractions out of a relative clause in short answers as grammatical, as in (2B), and take this as evidence against Merchant’s analysis. They argue that BAE is simply a fragment, and is interpreted through reference to the structure and meaning of the antecedent sentence (see Winkler & Schwabe 2003 and Winkler 2005, 2013 for an overview of the different theories of ellipsis).

The puzzle can be stated as follows: why do Merchant and Culicover & Jackendoff judge what appear to be structurally identical cases differently? Our proposal, which we outline in the course of this paper, is that the judgments do not reflect the grammaticality of the bare argument, but the complexity of interpreting it with respect to the discourse antecedent. The complexity of the interpretation is modulated in part by the introductory yes and no particle.

Our puzzle is particularly important because it bears on a central issue in syntactic theory: are sentences with missing material, such as sentences with ellipsis, simply fragmentary structures, or are they complete sentences with rich invisible structure? The standard view in generative grammar is that fragments are complete sentences with rich invisible structure. Grammarians such as Merchant have offered a range of arguments in support of this view, including the ill-formedness of certain cases of BAE such as (1B). Resolving the puzzle in favor of Merchant’s analysis provides additional support for the general uniformity approach (fragments are complete clauses). However, if it is shown that the ill-formedness of (1B) has a non-grammatical source, the argument for the uniformity approach is weakened.

2 Our Proposal: Referential and Discourse Ambiguity

The puzzle observation is that although the fragment answers cited above are syntactically identical, the judgments of the replies in (1) and (2) are not the same. Why does the data receive such contrasting acceptability judgments, even though the examples are in virtually all structural respects identical? In other comparable cases where a constituent in one sentence is in some way referentially related to a constituent in an antecedent clause, access to constituents in a relative clause do not have any special status compared with antecedents that are not in a relative clause. For example, a pronoun may have as its antecedent any DP that agrees with it in number and gender, including one that is a constituent of a relative clause, as in (7).

(7)

- A: John just bought a book that is very critical of the President.

- B: He is currently on vacation.

The pronoun he is referentially ambiguous – it may have either John or the President as its antecedent, and the fact that the latter is in a relative clause is irrelevant. The question is, why is the relationship between Charlie and Ben in (1) constrained, while the relationship between a very unusual language and Albanian in (2) is not?

Our solution to this puzzle is based on the observation that Merchant’s examples are introduced by no, while Culicover & Jackendoff ’s are introduced by yes. We propose that fragments exhibit a discourse function ambiguity and that the discourse particles yes and no eliminate this ambiguity. In addition, we claim that the responses introduced by no are computationally more complex than those introduced by yes, hence judged less acceptable.93

At the same time, antecedents of fragments that are located in relative clauses are more difficult to access than those that are located in the main clause. Thus there is another type of ambiguity at play here, namely the identity of the discourse antecedent of the fragment. Following a general line of analysis initiated in Centering Theory (Grosz et al. 1995), we suggest that there is a greater computational cost to identifying an antecedent DP of a fragment when it is in a lower ranked position in the antecedent sentence. That is, the head of the relative clause is more accessible than a referent within the relative clause.

In §3 we elaborate on what we mean by discourse function ambiguity, and show how the Merchant-Culicover-Jackendoff examples fit this rubric. In §4 we summarize the results of an experiment devised with the goal of testing the hypothesis that these examples are in fact discourse functionally ambiguous, and disambiguated by yes and no. In §5 we provide an explanation for the relative unacceptability of the no cases.

3 The Discourse Ambiguity of a Fragment

3.1 Discourse Functions

The type of ambiguity we are concerned with has to do with the discourse function (DF) or illocutionary force of an utterance. As is well-known, the DF of an utterance may be specified by the content of the utterance (as in performatives, Austin 1962). However, in most cases the DF of fragments is underdetermined by the form and literal meaning of the utterance. In such cases, discourse ambiguity results. (For concreteness we use the categories of DFs in Asher & Lascarides 2003.)

The present examples (1) and (2) illustrate just this type of ambiguity. A simple DP, like Charlie or Albanian, when it is a fragment, does not signal its DF through its form; it has no observable syntactic or morphological properties that indicate what its DF is. Rather, the DF must be inferred from the discourse context. The most relevant relations for our purposes are when a sentence supplements the previous sentence – adds further information to it – and when a sentence corrects the previous sentence – denies the truth of the previous sentence and replaces it with something that the speaker believes is more satisfactory.

In supplementation, the second sentence can add anything of relevance (8a); or it can express another similar situation either without ellipsis (8b) or with ellipsis (8c).

(8) Supplementation

-

- A: Sandy likes bitter lemon.

- B: Yes, and she drinks too much of it. [addition of ‘too much’]

-

- A: Sandy likes bitter lemon.

- B: Yes, and Bill likes elderberry juice. [addition of ‘Bill’ and ‘elderberry juice’]

-

- A: Sandy likes bitter lemon

- B:

- i. Yes, and elderberry juice too. [addition of ‘elderberry juice’]

- ii. Bill does too. [addition of ‘Bill’]

Correction appears to be somewhat more restricted. Typically, when one is offering a correction, it has to be a variant of what is being corrected. But it is possible to offer a correction with a syntactically unrelated sentence (9a), as long as a plausible connection can be found between the propositions. More common is an implicit correction, without ellipsis (9b) or with it (9c).

(9) Correction

-

- A: Sandy likes bitter lemon.

- B:

- i. No, she never drinks it. [literal correction of truth value of ‘Sandy likes bitter lemon’]

- ii.No, she’s a health fanatic. [implicit correction of truth value of ‘Sandy likes bitter lemon’]

-

- A: Sandy likes bitter lemon.

- B: No, Bill likes bitter lemon. [correction of ‘Sandy’ with ‘Bill’]

-

- A: Sandy likes bitter lemon.

- B:

- i. No, elderberry juice. [correction of ‘bitter lemon’ with ‘elderberry juice’]

- ii. No, Bill does. [correction of ‘Sandy’ with ‘Bill’]

Note especially the use of yes in Supplementation and no in Correction. Merchant’s examples (exemplified by (1B)) are Corrections, while Culicover & Jackendoff’s (exemplified by (2B)) are Supplementations. Crucially, the discourse function of the word Charlie as a Correction is restricted by no, while the discourse function of Albanian as a Supplementation is restricted by yes. That is, while in principle Charlie and Albanian could have different DFs than the ones that they have in these examples, yes and no disambiguate them in these specific contexts.

3.2 Computing Supplementations and Corrections

Our hypothesis is that the relative acceptability of the BAE fragments is determined in part by their function as Corrections or Supplementations, interpreted against the background of the antecedent sentence. This interpretation is an inferential process. We assume that the complexity of computing the inference contributes to the relative acceptability. We hypothesize that Corrections are in general computationally more complex than Supplementations as responses to yes-no-questions for several reasons, which we elaborate below.

Note first that while a fragment in discourse may be understood as a Supplementation without yes, it is difficult to understand a fragment as a Correction without no.

(10)

A: Does John speak an unusual language?

B: Yes, Albanian.

B′: Albanian.

B′′: No, English.

B′′′: English.

Response B′′′ in particular strikes us as a Supplementation (meaning that B thinks that English is an unusual language), not as a statement that John speaks English and not an unusual language. This observation leads us to hypothesize that other things being equal, Supplementation is the unmarked default and is thus computationally less costly than Correction. A similar idea was in fact proposed by Yadugiri (1986, 202–203), who argued that yes is computationally less demanding than no as an answer to a yes-no question, because yes “affirms not only the proposition … but also the presuppositional assumption, while no negates only the proposition but not the underlying presupposition. Hence if the addressee wishes to negate the underlying presupposition also the use of no alone proves inadequate.”94 Consider next the examples in (11).

(11)

A: Did Tom read the book that one of his sisters recommended?

B1: Yes, Lolita.

B2: No, Lolita.

B1’s answer may refer either to Nabokov’s book Lolita, or to one of Tom’s sisters. B2 on the other hand answers A’s question with no and thereby negates the whole propositional content of the question – Tom did not read the book that one of his sisters recommended. B2 also provides a correction of the negated statement –Tom read Lolita, not the book that one of his sisters recommended. The reading in which Lolita refers to one of Tom’s sisters is inaccessible because the full relative clause is in the scope of negation (cf. Goldberg 2006, Hooper & Thompson 1973), but subparts are inaccessible. Only the complete object of read can be corrected.

To put it more generally, the negation particle no takes scope over the complete focus phrase (FP), like other focus sensitive operators. The discourse particle yes does not have the scope taking function of a typical focus sensitive operator and therefore allows an elaboration of the most recent DP.

Our hypothesis about why the Corrections are judged to be less acceptable than the Supplementations rests on the following observations: Correction involves rejecting part of the antecedent sentence. In contrast to acceptance of the antecedent, which is a condition of Supplementation, rejection leaves the proposition of the question open – it is known what is not the case, but it is not known what is the case. Rejection of the presupposition associated with the antecedent leads to a greater processing effort than acceptance since it remains unclear which part of the sentence is to be corrected. In the case of (1), for example, no could mean (a) that it is not Abby who speaks the same Balkan language that Ben speaks but rather someone else, like e.g. John or Mary, (b) that Abby does not speak the same Balkan language that Ben speaks, but that she actually studies it, and so on. There are indefinitely many possible inferences that can be drawn from no, only restricted by the number of FPs no can associate with. (Conversely, in the absence of no, it is difficult, if not impossible to understand a fragment as a Correction, suggesting that Correction is not the default interpretation of the DF of a fragment.)

If the fragment relates to an item contained within a relative clause, the negative answer is infelicitous because the implications raised by no are not satisfied. In Merchant’s question (1A), what is at stake is whether Abby speaks the same Balkan language that Ben speaks and not whether someone other than Ben speaks the same Balkan language that Abby speaks. (1B) is infelicitous, it does not actually answer the question. No implies that the proposition of the question is being rejected (and Abby does not speak the same Balkan language that Ben speaks) but Charlie is not supposed to contrast with any element of the proposition. It is supposed to contrast with an element in the sentence that is not particularly in focus. Since Ben is contained in the relative clause, the element that matches the fragment DP is not at issue in the yes/no-question. It has to be identified on the basis of some additional information, such as context or focus, which is not marked in these examples (cf. Hartmann & Winkler 2013).

4 Experiments

With the foregoing points in mind we carried out an acceptability judgment experiment to test the effects of yes and no on interpretation. The key hypothesis is given in (12).

(12)

Hypothesis: No-answers (that is, Corrections) in yes-no-questions are computationally more complex than Yes-answers (that is, Supplementations). This greater complexity is reflected in lower acceptability.

The experiment tested three independent variables: Variable 1 concerns the effect of yes and no in fragment answers. Our prediction, other things being equal, is that yes in fragment answers is easier to understand and therefore will be preferred over no (cf. Yadugiri 1986). This is the Supplementation vs. Correction distinction. Variable 2 concerns whether judgments are facilitated by the presence of yes and no, as contrasted with the absence of such discourse markers. This is the Overtness vs. Covertness distinction. Finally, Variable 3 concerns the location of the antecedent of the fragment, specifically whether it is in a relative clause or not. This is the Relative Clause vs. No Relative Clause distinction.

Overall, there are eight conditions consisting of combinations of the three two-valued distinctions. An experimental test item is provided in the different conditions in (13).

(13) Test item in eight conditions:

- Overt Supplementation, NoRelClause

Did the friendly painter paint a big room of his mother’s house?

Yes, the spacious kitchen.

- Overt Supplementation, RelClause

Did Rufus call the friendly painter that painted a big room of his mother’s house?

Yes, the spacious kitchen.

- Overt Correction, NoRelClause

Did the friendly painter paint a big room of his mother’s house?

No, the antique front door.

- Overt Correction, RelClause

Did Rufus call the friendly painter that painted a big room of his mother’s house?

No, the spacious kitchen.

- Covert Supplementation, NoRelClause

Did the friendly painter paint a big room of his mother’s house?

The spacious kitchen.

- Covert Supplementation, RelClause

Did Rufus call the friendly painter that painted a big room of his mother’s house?

The spacious kitchen.

- Covert Correction, NoRelClause

Did the friendly painter paint a big room of his mother’s house?

The antique front door.

- Covert Correction, RelClause

Did Rufus call the friendly painter that painted a big room of his mother’s house?

The spacious kitchen.

Based on our discussion above, we predict that other things being equal, Supplementation will be judged better than Correction, Overt will be judged better than Covert, and NoRelClause will be judged better than RelClause. The best case should be Overt Supplementation+NoRelClause, and the worst should be Covert Correction+RelClause.

4.1 Design

Sixteen dialogues along the lines illustrated in (13) were distributed over 8 lists in a Latin square design. Each questionnaire was completed by 5 subjects each, so that a total of 40 native speakers of English rated 16 question/answer-pairs formed in accordance with the eight test conditions. The participants were aged 12 to 82; there were 19 speakers of American English, 18 speakers of British English; and one Australian, one New Zealander and one Canadian.

The experiment was designed as a closed scale task. The participants were introduced to the type of items they would encounter in the questionnaire through an accompanying e-mail and the introductory page. They were then presented with the scale and asked to rate B’s answers on a scale from 1 to 7. The scale was also presented at the top of each of the pages containing the test items.

Participants were instructed to use the whole range of the scale, to try to be spontaneous about their judgments and to put them down without changing them later. The test items were presented on five pages, each containing ten items. At the end of the line behind the reply, participants could choose from the numbers one through seven from a dropdown menu. In addition to the main test items, there were fillers and other conditions included in the questionnaire. We do not describe them here since they are not directly relevant to the central point of this paper.

4.2 Results

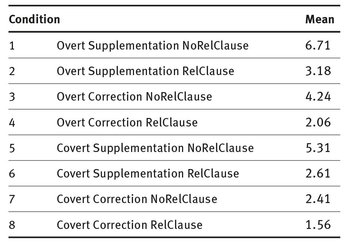

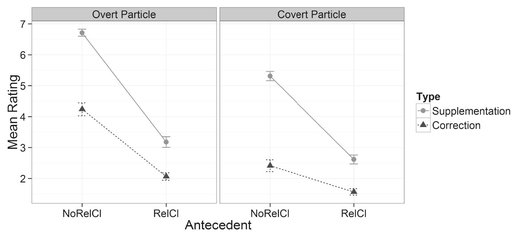

The results of the questionnaire support our predictions. They are summarized in Figure 2 and graphically represented in Figure 3.

The ratings were subjected to a 2 × 2 × 2 repeated measures ANOVAs with the within factors particle (overt vs. covert), type (supplementation vs. correction) and antecedent (relative clause vs. no relative clause), using participants (F1) and items (F2) as random factors. There was a significant main effect of all three factors: (i) Factor particle: The conditions with the particle yes/no overt were rated significantly higher than the conditions without an overt particle (F1 (1,39) = 39.0 p <.001, F2 (1,15) = 89.1, p <.001). (ii) Factor type: Supplementation forms were rated significantly higher than correction forms (F1 (1,39) = 239.7 p <. 001, F2 (1,15) = 47.3, p <.001). (iii) Factor antecedent: With the discourse antecedent of the fragment answer inside a relative clause, sentences are judged significantly lower than when the antecedent was not inside a relative clause (F1 (1,39) = 285.1; p <.001, F2 (1,15) = 252.7, p <.001). Additionally we found a significant interaction between particle and antecedent: the difference between the antecedent in a relative clause and outside a relative clause is significantly bigger when a yes/no-particle is present than when the particle is absent (particle*antecedent: F1 (1,39) = 21.1, p <.001, F2 (1,15) = 20.5, p <.001). The second interaction is found between type and antecedent: the difference between the antecedent in a relative clause and outside a relative clause is significantly larger when the answer provides supplementation (type*antecedent F1 (1,39) = 49.6, p <.001, F2 (1,15) = 70.8, p <.001).

Figure 3: Mean Ratings per Condition

One of our key predictions was that Supplementation is judged to be more acceptable than Correction, regardless of the syntactic structure of the antecedent. That this is the case is seen in the main effect of the factor type (see above), and illustrated in Figure 4: Condition 1 is preferred to Condition 3, Condition 2 is preferred to Condition 4, Condition 5 is preferred to Condition 7, and Condition 6 is preferred to Condition 8.

The experimental results show that locating the antecedent of the fragment in a relative clause has a substantial effect in reducing acceptability, as Merchant originally observed. This is the main effect of the factor antecedent. However, Correction also has a substantial effect in reducing acceptability, even in the absence of a relative clause. This is seen in the main effect of the factor type. Supplementation utterances are judged better than Correction throughout. Thus the judgments on Merchant’s examples, which combine a relative clause with Correction, are lower than those on the Culicover & Jackendoff examples, which combine a relative clause with Supplementation. Finally, the omission of discourse markers appears to contribute comparable unacceptability regardless of whether the fragment has to be understood as a Correction or Supplementation; this may reflect a floor effect.

5 An Explanation

At first glance, the experimental results appear to support Merchant’s account of examples such as (1), since interpretation of a fragment with respect to an antecedent in a relative clause is substantially degraded compared with identical examples in which the antecedent is not in a relative clause. However, the fact that examples with Correction are substantially degraded compared with identical examples with Supplementation regardless of the syntactic structure of the antecedent shows that the severe ill-formedness of Merchant’s examples is not due simply to the relative clause.

It therefore appears that there are two factors that contribute to the degradation of judgments to be accounted for: the location of the antecedent of the fragment inside of a relative clause, and Correction. Our proposal, is that both contribute a computational cost to the interpretation. Individually, this computational cost produces judgments of lowered acceptability, and when they are combined, they produce the severe unacceptability observed by Merchant. This severe unacceptability gives the illusion of ungrammaticality.

To understand how these factors contribute to unacceptability, we must understand the process by which the examples are interpreted. Consider first the case of overt Supplementation with a relative clause, as in (14).

A: Did Rufus call the friendly painter that painted a big room of his mother’s house?

B: Yes, the spacious kitchen.

We assume that the adjacency of the two utterances licenses the presumption of Relevance, in the sense of Sperber & Wilson (1995). The use of yes signals that B’s utterance is a Supplementation. The computational task is to identify what is being supplemented. Because there are several DPs in the preceding sentence, there is an ambiguity that this computation has to resolve – which DP is the antecedent of the Supplementation? Following Centering Theory (Grosz et al. 1995), the candidates are ranked as follows.

(15) subject of main clause > object of main clause > argument of relative clause

Thus the computation (in 14) has to check first Rufus, then the friendly painter and finally a big room of his mother’s house in order to identify a plausible antecedent for the spacious kitchen. We assume that the lower ranking of the plausible antecedent has the consequence of increasing the computational cost of finding the antecedent. This assumption is consistent with the observation in Centering Theory that other things being equal, lower ranked DPs are less likely candidates as antecedents for similar discourse computations, such as coreferential dependency. Consider next the contribution of overt Correction.

(16)

A: Does John speak an unusual language?

B′′: No, English.

Our results show that the use of the fragment as a Correction is substantially degraded (Conditions 1 vs. 3). We attribute this difference to the amount of processing that it required for A to interpret what B means, as summarized in Figure 5. No signals that English is a Correction. First a suitable antecedent must be found. Again, John is not a good candidate, but an unusual language is. But in this case, it is now necessary to determine in what sense English is a Correction to an unusual language.

| Utterance | Action | |

|---|---|---|

| Does John speak an unusual language? | 1 | Ask question about proposition “John speaks an unusual language.” |

| No | 2 | Deny proposition “John speaks an unusual language” |

| 3 | Conclude “John does not speak an unusual language” | |

| English | 4 | Add information “English”. |

| 5 | Figure out what “English” has to do with “John does not speak an unusual language” | |

| 6 | Recognize that English is not an unusual language | |

| 7 | Conclude that John speaks English |

One inferential step is recognizing that in spite of the denial of the proposition “John speaks an unusual language,” the fragment English is also intended to assert something. Another is determining what it is that is intended.

The additional steps in this dialogue can be eliminated by explicitly responding “No, he speaks English.” This eliminates the need to identify the function of English both as a statement about what language John speaks (step 5 in Figure 5), and as triggering the knowledge that English is not an unusual language as a rationale for the no answer (step 6 in Figure 5). Consider the further complication of referential ambiguity in (11B2), here repeated in (17A,B):

(17)

A: Did Tom read the book that one of his sisters recommended?

B: No, Lolita.

In (17B), Lolita may have Tom, one of his sisters or the complete noun phrase the book… as an antecedent. In the first case the interpretation is as in (18), in the second case the interpretation is as in (19).

(18) No, Lolita read the book that one of his sisters recommended.

(19) No, Tom read the book that Lolita recommended.

In addition, Lolita may be the name of the book. In this case, then, the referential ambiguity further complicates the computation of the Correction. Note, in all these Corrections, Lolita must be contrastively focused. Compare now the contribution of yes in (20).

(20)

A: Does John speak an unusual language?

B: Yes, Albanian.

In this case, the computational cost is modest. Yes signifies that the presupposition is accepted, Albanian is a Supplementation, its antecedent must be found: John is not a good candidate, but an unusual language is. The interpretation of the fragment can be substituted into the interpretation of the antecedent sentence along the lines of Figure 6.

| Utterance | Action | |

|---|---|---|

| Does John speak an unusual language? | 1 | Ask question about proposition |

| Yes | 2 | Confirm proposition “John speaks an unusual language” |

| Albanian | 3 | Add information “Albanian” |

| 4 | Accept that Albanian is an unusual language | |

| 5 | Conclude that John speaks Albanian |

Figure 6: Processing Steps of Supplementation.

Returning to our main point, we have observed that there is an inherent ambiguity in discourses involving fragments. The discourse function of the fragment itself is ambiguous, and if the fragment is a DP, there is an additional ambiguity regarding its discourse antecedent.

The function of yes and no is that of disambiguation. But even with disambiguation, Correction (with no) requires more computational effort than Supplementation (with yes) in order to determine the intended meaning of the fragment. On this basis, we account for the difference between the Merchant examples, which are Corrections, and the Culicover-Jackendoff examples, which are Supplementations.

An additional ambiguity concerns the identification of the antecedent of the DP. When the antecedent sentence lacks a relative clause, there is one potential antecedent in the examples considered. But when the antecedent sentence has a relative clause, a referential ambiguity is introduced, further complicating the processing.

In sum, we conclude that while there is a genuine effect of the relative clause structure on the acceptability of fragments in discourse, it is a mistake to take this effect to be unequivocal evidence for invisible structure in elliptical constructions. Rather, we argue, that the evidence adduced for invisible structure in fact reflects the complexity of processing the ambiguity of discourse function and resolving the referential ambiguity. The possibility exists, of course, that there is a grammatical contribution to the unacceptability judgments of such examples. But a conclusive demonstration that grammatical factors are responsible for the markedness of these examples requires that it be shown that a processing account cannot explain all of the variance. Conversely, to rule out grammatical factors, it would be necessary to construct a fully explicit computational model that accounts for all of the observed effects. In the absence of such an account, it is not possible to draw any final conclusions at this point on the basis of our data. Future research on graded grammaticality and psycholinguistic modeling will show whether the account that we proposed here is a promising one.

References

Asher, Nicholas & Alex Lascarides (2003) Logics of Conversation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Austin, John L. (1962) How to Do Things With Words. New York: Oxford University Press.

Chomsky, Noam (1973) Conditions on Transformations. In: S. Anderson & P. Kiparsky (eds.) Festschrift for Morris Halle. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 232–286.

Culicover, Peter W. & Ray Jackendoff (2005) Simpler Syntax. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Drubig, Hans Bernhard (1994) Island Constraints and the Syntactic Nature of Focus and Association with Focus. Arbeitspapiere des Sonderforschungsbereichs 340. Tübingen: University of Tübingen.

Goldberg, Adele E. (2006) Constructions at Work: Constructionist approaches in context. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Grosz, Barbara J., Scott Weinstein & Aravind K. Joshi (1995) Centering: A Framework for Modeling the Local Coherence of Discourse. Computational Linguistics 21, 203–225.

Hartmann, Jutta & Susanne Winkler (2013) Investigating the Role of Information Structure Triggers. Lingua 136, 1–15.

Holmberg, Andres (2013) The Syntax of Answers to Negative yes/no-Questions in English and Swedish. Lingua 128, 31–50.

Hooper, Joan & Sandra A. Thompson (1973) On the Applicability of Root Transformations. Language 4, 465–497.

Krifka, Manfred (2006) Association with Focus Phrases. In: Valeria Molnár & Susanne Winkler (eds.), The Architecture of Focus. [Studies in Generative Grammar 82.] Berlin/New York: Mouton de Gruyter, 105–135.

Merchant, Jason (2004) Fragments and Ellipsis. Linguistics and Philosophy 27, 661–738.

Ross, John R. (1967) Constraints on Variables in Syntax. Unpublished doctoral dissertation. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Sperber, Dan & Dierdre Wilson (1995) Relevance: Communication and Cognition, Oxford: Blackwell.

Winkler, Susanne (2005) Ellipsis and Focus in Generative Grammar. [Studies in Generative Grammar 81. Series Editors: Harry van der Hulst, Henk van Riemsdijk & Jan Koster.] Berlin, New York: de Gruyter.

Winkler, Susanne (2013) Syntactic Diagnostics for Island Sensitivity of Contrastive Focus in Ellipsis. In: Lisa Cheng & Norbert Corver (eds.) Diagnosing Syntax. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 463–484.

Winkler, Susanne & Kerstin Schwabe (2003) Exploring the Interfaces from the Perspective of Omitted Structures. In: Kerstin Schwabe & Susanne Winkler (eds.) The Syntax-Semantics Interface: Interpreting Omitted Structures. Amsterdam, Philadelphia: Benjamins, 1–27.

Yadugiri, M. A. (1986) Some Pragmatic Implications of the Use of Yes and No in Response to Yes-No Questions. Journal of Pragmatics 10, 199–210.