30

Higher Education in India

G. Karunakaran Pillai

30.1 Introduction

In the 21st century, the development of higher education figures among the topmost national priorities across nations. In the World Conference on Higher Education organized by UNESCO in October 1998, representatives of 128 nations met at Paris to discuss the form of higher education relevant for the 21st century. The conference reaf-firmed the need for access to higher education and the concern for equity. Setting out the mission for higher education, the conference resolved that ‘beyond its traditional functions of teaching, training, research and study’, higher education must ‘promote development of the whole person and train responsible, informed citizens, committed to working for a better society in future’. In 1998, the World Bank and UNESCO convened the Task Force on Higher Education, and after 2 years of research and intensive discussion and hearing, the Task Force concluded that without more and better education, developing countries would find it difficult to benefit from the global knowledge-based economy. The report presents a powerful message that ‘higher education is no longer a luxury; it is essential for survival’. The Commission on International Education of American Council on Education recognized the need of international competence and suggested that the government and the private sector should support higher education so as to reorient it to the new global realities. The report of UK’s National Committee of Inquiry into Higher Education sets out a vision for the future development of education in the 21st century. The report makes out a case for higher education as a lifelong learning process and pleads for widening the access. On the financing of higher education, the report says that the investment in higher education is an investment for the future. Therefore, the state should contribute the costs, but it is right too that the costs should be shared with those who benefit from improved and expanded higher education. The extracts from the various reports bring out that education is a major political priority and high-quality human capital is developed in high-quality education systems.

The Indian higher education system is the largest in the world, next to the USA, with 504 universities and university-level institutions which include 243 state universities, 53 state private universities, 40 central universities, 130 deemed universities, 33 institutions of national importance and five institutions established under various state legislations and 25,951 colleges including around 2,565 women colleges. The higher education system in India has undergone massive expansion in the post-Independence period with a national resolution to establish several universities, technical institutes, research institutions and professional and non-professional colleges across the country to generate and disseminate knowledge coupled with the noble intention of imparting easy access to higher education to the common man. With public funding no longer in a position to take up the challenging task of expansion and diversification of higher education, to meet the continuously growing demand, the need for bringing in private initiatives in a massive way to meet the various challenges is high. New developments in science and technology, media revolution, the internationalization of education and the ever-increasing competitive environment are revolutionalizing the higher education scene. There are exhortations, to the policy planners of higher education, emanating from economic reforms and World Trade Organization (WTO) formulations, such as the withdrawal of subsidies, reduced control of the state, larger privatization and designing the courses to meet the human resources needs of the markets. The new regime under the WTO, where competence is the cardinal principle of success in international operations, the nation should exploit its excellent potential, of higher education, to export to foreign countries.

30.1.1 Evolution of Higher Education in India

In ancient India, the system of Gurukulam was the pivot of higher education, which was structured around a distinguished rishi or a guru. The education was based on an integrated system of dharma (religion), darshan (philosophy), shaastra (economics), and niti (ethics). Before the arrival of British, education was institutionalized. Warren Hastings, the first Governor General of India, partially recognized the duty to promote education and, accordingly, established the Calcutta Madrasa in 1781 to conciliate the Muslims to qualify them for responsible and lucrative offices in the state. In 1791, the Banaras Sanskrit College was established. Charles Grants, the father of modern education in India, advocated western knowledge through the medium of English. In 1811, Lord Minto recommended the establishment of Hindu colleges and Muslim colleges to win the confidence of the Indians. The East India Company, by the Charter Act of 1813, laid the foundation of the English educational system. In 1834, the Committee of Public Instruction was set up under Lord Macaulay and he presented the minutes regarding the new educational policy. In 1837, English was made the language of education.

Modern education in India started in 1854, with the famous despatch of Sir Charles Wood, which was the equivalent of the Magna Carta in English education in India. The modern system of higher education actually started in 1857, when three universities of Calcutta, Bombay and Madras were established on the model of the London University. In 1882, there were 27 colleges in Bengal, six in Bombay, 25 in Madras, 11 in the North Western Province, two in Punjab and one in the Central Provinces. In 1892, the Indian Universities Commission was appointed to inquire into the conditions and prospects of universities. The recommendations of the commission were embodied in the Indian Universities Act, 1904 and the functions of universities were centralized. The reform measures of Lord Curzon, and the regulations of affiliation, hindered private enterprise in higher education and the immediate effect was the decline in the number of colleges from 192 to 170 from 1902 to 1912. In pursuance of the Educational Policy of 1913, five universities were set up between 1916 and 1918 and five more in the 1920s. The period from 1857 to 1947 was marked by a heavy expansion of higher education. In 1857, there were three universities, 27 colleges with 5,399 students. This rose to 19 universities, 496 colleges with 2.41 lakh students in 1947. Most of the colleges were under private management, mainly Christian missionaries and wealthy Indians.

Free India inherited a system of higher education, which was an integral part of the colonial setup. In 1948, the University Education Commission was set up under the Chairmanship of Dr S. Radhakrishnan. The Commission suggested improvement and extension of university education to suit the present and future requirements of India. The Commission discussed all aspects of university education, particularly changes required in the curriculum, examination and organization. It recommended that university education should be placed on the concurrent list. The recommendations of the Commission gave a direction to the development of higher education in India.

The constitution of India provides the basic framework for policies and the important provisions regarding higher education are as follows:

- Article 24, under Fundamental Rights, Educational Rights and Protection of the Interests of Minorities.

- Under Article 30, Rights of Minorities to establish and administer education.

- Articles 15 and 17, under Fundamental Rights, educational rights of weaker sections.

- Under Article 46, promotion of educational and economic interests of scheduled castes, scheduled tribes and other weaker sections.

- Under Article 28, freedom to attend religious instruction or religious worship in educational institutions.

- Article 15, under Fundamental Rights, Woman’s Education.

- Article 351, special directive for the development of Hindi language.

The University Grants Commission (UGC), the apex body of higher education, began to function in 1954. Early in 1956, the Parliament enacted the UGC Act. The UGC is responsible for the coordination, determination and maintenance of standards, and release of grants for higher education in India. The UGC, a statutory body, has the power to disburse funds and fix standards in teaching, examination and research in the college and university education system. The UGC also advises the central and state governments on the steps necessary for higher education. It frames such regulations as those on the minimum standards of the qualification of teachers, and monitoring and evaluation of teaching and research programmes, and implements schemes and programmes for increasing excellence and enhancing the standards of institutions of higher education.

30.1.2 Growth of Institutions and Enrolment in the Higher Education System

At the time of Independence, there were only 20 universities, 496 colleges and 2.15 lakh students in India. Thus, the higher education system was miniscule. Between 1950 and 2008, the number of universities has increased from 20 to 431, colleges from 500 to 20,677 and the teachers from 15,000 to 5.05 lakhs, and the enrolment of students increased from 1 lakh to over 116.12 lakhs. The stage-wise enrolment of students in universities and affiliated colleges is presented in Table 30.1.

TABLE 30.1 Statewise Statement of Universities, Deemed Universities and Institutions of National Importance, Colleges and Enrolment of Students in 2003–04

Source: University Grants Commission, Annual Report 2003–04.

As is evident from Table 30.1, Maharashtra has the largest number of colleges, followed by Andhra Pradesh, Uttar Pradesh, Karnataka, Tamil Nadu and Madhya Pradesh. The highest enrolment of women students is in Kerala, followed by Goa. Bihar accounts for the lowest enrolment of women students.

30.1.3 Stage-Wise and Faculty-Wise Enrolment

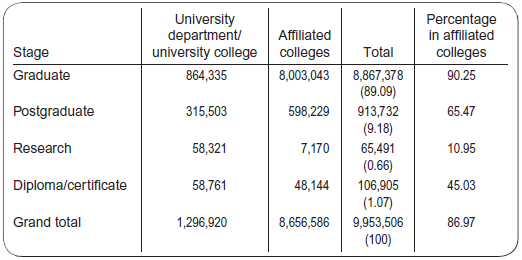

A majority of the students of the higher education system (89.09 per cent) are enrolled for a variety of courses at the under-graduate level. The percentage enrolled for master’s level courses is 9.18. The percentage of students doing research constitutes only 0.66 per cent. The students enrolled for diploma and certificate course are barely 1.07 per cent (Table 30.2).

Most of the students in the higher education system are enrolled in affiliated colleges (90.25 per cent) at undergraduate level. Nearly two-thirds of all post-graduate students are in colleges. In contrast, 89.05 per cent of research students are in universities. Thus, the foundations of higher education are laid in colleges.

The faculty-wise enrolment of students during 2003–04 is given in Table 30.3. As is evident from the table, of the total enrolment, 45 per cent of the students are in the faculty of arts followed by 20 per cent in science and 18 per cent in commerce and management. Thus, 83 per cent of the enrolment was in the faculties of arts, science and commerce and management. The remaining 17 per cent is in professional faculties. The enrolment in agricultural courses has been just 0.59 per cent and in veterinary science it is 0.15 per cent. This is a clear indication for a change in policy, which can reduce the disparity in the enrolment of students in various faculties.

TABLE 30.2 Stage-wise Enrolment of Students, 2003–04

Note: Figures in brackets denote percentage of the total.

Source: University Grants Commission, Annual Report 2003–04.

TABLE 30.3 Faculty-wise Enrolment of Students, 2003—04

Source: University Grants Commission, Annual Report 2003–04.

30.1.4 Faculty Strength

The number of teachers in universities and colleges was 4.57 lakhs in 2003–04. Of these, 83 per cent are in colleges and the remaining 17 per cent in university departments and university colleges (Table 30.4).

The number of research degrees (Ph.D.) awarded by various universities was 13,733 in 2002–03. Of these, the faculty of arts had the highest number, 5,797, followed by science with 5,034 research degrees, agriculture (1,042), commerce and management (857), engineering and technology (779) and medicine (243). The faculties of arts and science together accounted for 69 per cent of the total number of research degrees awarded.

30.1.5 Growth in the Enrolment of Women

There has been a phenomenal growth in the enrolment of women in higher education since Independence, from less than 10 per cent on the eve of Independence to 40.22 per cent in 2003–04. The pace of growth has been faster in the last two decades. Kerala, with 60.6 per cent, topped in terms of woman enrolment, followed by Goa (58.8 per cent) and Punjab (51.4 per cent) (see Table 30.1). There were 17 states with a higher enrolment of women than the national average of 40.22 per cent. Bihar recorded the lowest enrolment of women at 24.3 per cent.

TABLE 30.4 Distribution of Teaching Staff in University Departments and Affiliated Colleges in 2003–04

*Include principals and senior teachers who are equivalent professors.

Source: University Grants Commission, Annual Report 2003–04.

The enrolment of women as a percentage of the total enrolment has been consistently going up at all stages of higher education. Enrolment of women is the highest at the postgraduate stage (42.18 per cent) as compared to other stages—graduates (40.1 per cent), research (39.04 per cent), and diploma and certificate (33.8 per cent).

The faculty-wise enrolment of women in 2003–04 shows that the enrolment of women in the faculty of arts was the highest (51.01 per cent), followed by the faculty of science (20.22 per cent), commerce and management (16.43 per cent), engineering and technology (4.13 per cent) and medicine (3.63 per cent).

Education of women in India has been regarded as a major programme. It has been examined by a number of committees, namely the National Council of Women’s Education (1959), the Committee on Differentiation of Curricula Between Boys and Girls in 1961 and the Bhaktavatsalam Committee (1961), which studied the problem in six states where the education of girls is less. In 1971, a committee was appointed to examine the problems related to the status and advancement of women. In its report submitted in 1974 entitled ‘Towards Equality’, the committee emphasized the development of more employment opportunities, particularly of a part-time nature, to enable the women to participate more in productive activities, and the creation of an employment information and guidance service for women entering higher education. The National Policy on Education, 1986, emphasized the role of education as an agent for change in the status of women and an interventionist role in the empowerment of women.

For the fulfillment of the commitment of ‘Education for Women’s Equality’, the Ninth Five Year plan (1997–2002) envisaged plans for free education even at the college level, including professional courses, for better empowerment of women. The Tenth Five Year Plan (2002–07) aimed to carry forward the goal of education for women’s equality as advocated by the National Policy of Education (1986) (revised in 1992) by reducing the gender gap at the higher education level. The National Policy of Empowerment of Women was declared in April 2001 to empower women as agents of socio-economic change. It highlights steps for eliminating bias in educational programmes and to institute plans for free education of girls up to the college level, including professional levels.

30.1.6 Technical Education

Technical education is one of the most effective ways to create skilled manpower for developmental purposes. The impulse for technical education came from the British, as the East India Company needed doctors for the army, judges for the courts and engineers for constructing roads, canals and government buildings. The Native Medical Institute was established in Calcutta in 1822 and education in engineering began with the Engineering Institute in Bombay in 1824. In 1947, there were 28 degree-level and 41 diploma-level institutions for engineering and technology. In 1945, the Government of India established the All India Council for Technical Education (AICTE) to stimulate and coordinate the provision of facilities for technical education. In 1987, the AICTE was made a statutory body for the proper planning and coordinated development of the technical education system, and the regulations and the proper maintenance of norms and standards in the technical education system.

There has been a spectacular expansion of technical education since independence. Technical education during the first three five-year plans devoted to expansion to meet the growing demand for technical personnel at the diploma, degree and post-graduate levels. From the Fourth Plan onwards, emphasis was shifted to the improvement of quality and standards of technical education.

At the beginning of the Eighth Five Year Plan (1992–97), there were 200 recognized technical education institutions at the first degree level and more than 560 polytechnics at the diploma level with an annual admission capacity of 40,000 and 80,000 students, respectively. There were 140 institutions of post-graduate studies and research in several specialized areas with an annual capacity of 9,400 students. The thrust areas identified in the plan were modernization and upgradation of infrastructural facilities and quality improvement. The New Industrial Policy (1991) created an environment, which required the institutions to adopt a new role as leaders in current and future technology development. Four areas were identified for further action: (i) technology development; (ii) international consultancy; (iii) resource mobilization and setting up of corpus funds; and (iv) industrial foundation.

The Ninth Plan (1997–2002) emphasized the growing need for manpower and the task of improving the quality of technical education. The number of technical and management institutions rose to 4,791 in 2001–02 with an annual intake of 6.7 million students. The AICTE granted approval to set up 1,715 institutions in the private sector, offering courses in engineering and technology, management, architecture, town planning, pharmacy and applied arts and crafts.

During the Tenth Plan (2002–07) period, there was a continuing focus on technical and management education, including research in technology. The recommendations of the Rama Rao Committee on enhancing the quality of post-graduate education and research through the enhancement of scholarships and fellowships, and better networking among institutions, will be implemented during the Tenth Plan. Technology centres will be established or strengthened at IITs, RECs, selected engineering colleges, management institutions and Technical Teachers Training Institutes (TTTIs). Full-fledged departments of biotechnology will be established for developing new and emerging technology areas, like advanced new material technology, biotechnology, nanotechnology, bio-informatics and robotics to provide a competitive edge to the country in the long-term development of biotechnology potential.

The task force on HRD 2001, constituted by the Planning Commission, to suggest strategies for India’s transformation into a knowledge superpower, recommended: (i) creating information on IT manpower; (ii) promoting initiative in HRD in IT; (iii) monitoring the intake and out-turn of IT professionals; and (iv) setting up of exclusive IT institutes. Basically, the Tenth Plan objectives, key issues and focus will be on increasing the quality of education and research in technology.

30.2 Policy of Higher Education

The colonial education policy, drafted by Lord Macaulay in 1834, continued without any change for 20 years after Independence, even though education required a fresh look. The government realized the need for a change in the education system and also a comprehensive resolution on the National Policy on Education. Thus, in 1964, an Education Commission under the chairmanship of Prof. D. S. Kothari was appointed to advise the government on ‘the national pattern of education and the general principles and policies for the development of education at all stages and in all aspects’. The commission submitted its report to the government in 1966. On the basis of the recommendations made by the Education Commission, the government issued a resolution on the National Education Policy in 1968.

30.2.1 The National Policy on Education, 1968

The National Policy on Education 1968 is considered to be a major landmark in the history of education in the post-Independence period. It became the basis of reforms in the educational system in India. A radical reconstruction of the education system was emphasized in the policy. It stressed the improvement in the quality of education at all stages and greater attention to science and technology, the cultivation of moral values, and a closer relation between education and the life of the people. It recognized the need for a revolution in education, which, in turn, will set the motion the much-designed social, economic and cultural revolution.

30.2.2 UGC Policy Frame for University Education

In 1978, the UGC prepared a policy frame for higher education outlining the basic philosophy and strategies for the development of colleges and universities to improve the standard of higher education and research over the next 10–15 years. This policy frame aimed at the creation of the basic conditions for the development of university education. The policy frame called for coordinated and collaborative efforts of the centre, the states and the public to create a new educational system.

30.2.3 Draft National Policy on Education, 1979

The Janata Government came to power in 1977 and revised the National Policy of Education, 1968. The government appointed the Ishwarbhai Patel Committee and Adiseshiah Committee to review the education policy. On the basis of the recommendations of these committees, the draft of the revised National Policy of Education was released in 1979. The policy aimed to reorganize the present system of education in light of contemporary Indian realities and requirements. It emphasized that education should strengthen the values of democracy, secularism and socialism. The Draft National Policy stressed that the central government would review the implementation of the national policy on education every 5 years and modify it in light of its experience. However, the policy was not implemented due to the change of government in the centre.

30.2.4 The National Policy on Education, 1986

In 1980, the Congress Government resolved to promote the National Policy on Education, 1968. At this time, a variety of new challenges and social needs had emerged and it was imperative for the government to formulate a new education policy. The status report entitled ‘Challenges of Education—The Policy Perspectives’ was prepared by the Ministry of Education in 1985. There was a nationwide debate on this report. This became the basis for the National Policy of Education, 1986, which contemplated dynamism in higher education. This dynamism will be expressed through—(i) consolidation and expansion of institutions; (ii) development of autonomous colleges and departments; (iii) redesigning of courses; (iv) strengthening of research; (v) training of teachers; (vi) improvement in efficiency; (vii) creation of a structure for coordination at the state and national level; and (viii) mobility.

With the change in the government in the centre in 1990, a review committee (under the Chairmanship of Acharya Ramamurti) was appointed to review the National Policy on Education, 1986. The review committee submitted its report in December 1990 entitled ‘Towards an Enlightened and Human Society’. The committee was guided by the philosophy of equity and social justice, and decentralization of educational management. When the Congress government came to power in 1991, the Ramamurti report was not taken into consideration. A new committee was appointed in July 1991 under the chairmanship of Janardhana Reddy to review the implementation of various parameters of National Policy of Education, 1986. The committee submitted its report in 1992 and, accordingly, finalized and revised the National Policy on Education, 1986, in 1992.

30.2.5 Revised National Policy on Education, 1992

The review committee viewed that the unplanned proliferation of colleges and universities was the bane of higher education. For a planned development of higher education in the Revised National Policy on Education, 1992, the strategies of the plan of action were—(i) the establishment of a State Council of Higher Education as a statutory body in all the states during the Eighth plan period (1992–97) for planning and coordination of higher education; (ii) in partnership with the UGC, every state government was to undertake a survey of the existing facilities for higher education; and (iii) the Central Council of Rural Institutions was to be set up to promote rural education in the lines of Mahatma Gandhi’s revolutionary ideas on education. The plan of action was spread over years from the Seventh plan (1985–90) to Tenth plan (2002–07) and beyond.

The Revised National Policy on Education, 1992, was in line with the National Policy of 1986. Like the earlier policy, it did not go much beyond a remarkable collection of platitudes. It has been criticized by Amatya Sen and Jean Dreze. According to Dreze and Sen ‘the implication of these vague policies is that they have opened the door to further inconsistencies between stated goals and actual policy’. The lamentable history of the post-Independence education policy is of diverse kinds of inconsistencies and contradictions including—(i) a confusion of objectives; (ii) inconsistencies between stated goals and actual policy; and (iii) a specific contradiction between stated goals and resource allocation.

30.3 Financing Higher Education

Although expenditure on education grew at a faster rate than those in other social sectors, the five-year plan outlay on education showed a declining trend, as is evident from Table 30.5. The outlay on education constituted 7.8 per cent during the First Plan period and continuously declined before reaching 2.8 per cent during the Sixth Plan period. Thereafter, it improved slightly and constituted 4.5 per cent during the Eighth Plan. The outlay on elementary education constituted 58 per cent during the First Plan, declined to 33 per cent during the Seventh Plan and reached 46 per cent during the Eighth Plan. The outlay on university education constituted only 9 per cent during the First Plan, but it registered an increase in subsequent plans before reaching the peak level of 37.6 per cent during the Seventh Plan period. The outlay on technical education showed wide fluctuations during the plan period. The fall in the outlay on education in successive five-year plans is suggestive of the low priority accorded to education in the planned development of the country.

Public expenditure on education is one of the lowest in India. In most countries, the education expenditure accounts for 6–10 per cent of the GNP. In India, it is 3.5 per cent of the GNP, which is lower than most of the developing countries. We are far behind the target of spending 6 per cent of the GNP on education, as recommended by the National Education Commission (1964–66). The expenditure on higher education is also one of the lowest in India, declining from its peak of 1 per cent of the GNP in 1980–81 to less than 0.6 per cent currently. It is 2.7 per cent in the US, 1.6 per cent in Australia, 1.1 per cent in Japan, 0.9 per cent in the UK, 0.8 per cent in Kenya and 0.4 per cent in China. Given the fiscal pressure, and the high priority assigned to primary education, the financial future of higher education is bleak.

TABLE 30.5 Expenditure on Education in the Five-Year Plans

Source: Government of India (Planning Commission) Five Year Plan Documents, New Delhi, Ministry of Human Resource Development, Annual Reports (Various Years).

Figures in brackets denote the percentage of the total.

In 2007–08, the share of higher education and technical education was 11.83 per cent and 5.33 per cent, respectively, of the total expenditure on education. The central plan and non-plan expenditure increased at an annual rate of growth of 31 per cent and 10 per cent, respectively, during the Tenth Plan, while in the first 3 years of the Eleventh Five Year Plan, it increased at an annual growth rate of 54 per cent and 34 per cent, respectively. The share of the central plan and non-plan and that of the state plan and non-plan in the public expenditure in higher education is 8 per cent and 13 per cent and 6 per cent and 73 per cent, respectively. From the Ninth to Tenth Five Year Plan, the central plan expenditure went up by 86 per cent and the state plan expenditure by 76 per cent. The central plan expenditure from the Tenth to Eleventh Five Year Plan increased by a little over 10 times.

Universities in India obtain funds from the following nine sources—(i) government grants; (ii) government grants and allowances or loans to students; (iii) students fees and charges; (iv) contracts for research, courses and consultancy; (v) earning from intellectual property; (vi) commercial activities; (vii) investment of funds; (viii) borrowing of funds; and (ix) gifts and donations. Of the nine sources, government grants constitute the bulk of the funds of universities. The dependence of government funds has increased from 57 per cent during 1950–57 to 80 per cent currently. The share of student fees decreased from 20 per cent to 8 per cent. Student fees in India is probably the lowest in the world. The internal resources of the universities have been dwindling as a percentage of their annual maintenance expenditure. The private contribution to education in the form of donations and endowments, which are the hallmark of pre-Independence period, has declined considerably.

The burden of ever-increasing recurrent costs is perhaps the most important problem of university financiers. The recurrent expenditure include outlays on salaries, maintenance, consumables and financial concessions. These comprise over 94 per cent of the total expenditure of universities. The upward pressure on recurrent costs has increased the cost of pedagogical materials, such as textbooks, journals, laboratory equipments, consumables and others several times.

The decline in resources has been compounded by the internal inefficiency in incurring expenditures by universities. Salaries of the staff form the largest part of university budgets. The salary component is very high on account of the low teacher-to-student ratio, and the high teaching-to-non-teaching staff ratio. The teacher-to-student ratio is low in several universities, for instance, in central universities like the Aligarh Muslim University, it is 1:9, 1:10 in the Banaras Hindu University, 1:10 in the Jawaharlal Nehru University, while in state universities like the University of Madras, it is 1:6 and Karnataka University 1:8, while the University of Kerala has one of the lowest ratio of 1:16. Regarding the teaching-to-non-teaching staff ratio, at present, there are no norms. The ratio of the teaching and non-teaching staff should ideally be 1:1.5, the norms which some of our IIMs and IITs are trying to achieve.

30.3.1 External Efficiency

Universities are affected by two types of external efficiency, namely rising graduate unemployment and declining research output. The reasons behind the rise in graduate unemployment are as follows—(i) the role of the public sector, or the major employer of graduates, has diminished; (ii) the aggregate demand for skilled labour remained sluggish; (iii) university education is highly subsidized. Subsidization is an inequitable and inefficient educational investment. Subsidies are regressive social spending, because students enrolled in universities are disproportionately from the upper end of the income strata; (iv) the expansion of higher education has been completely unplanned, unwieldy and chaotic. There has been unplanned and fiscally unsustainable growth in enrolment; and (v) high enrolment in arts and humanities, as these traditionally lead to government employment.

The country failed to utilize the vast research potential of the national R&D work of universities for advanced scientific training and research. Many universities are mere teaching institutions. Thus, their research is rarely intended for practical application, leading to low-key university-industry interaction.

30.4 The Problems of the Higher Education System

The higher education system in India is at a crossroad. It is facing greater challenges in the 21st century. First, the globalization has far-reaching impact on education. The linking of the Indian economy with that of the world will create a more favourable environment of employment for our best-trained youth in all discipline and all subjects. Secondly, the information and communication revolution is helping transcend the barriers of time and place, as well as space constraints. Thirdly, the higher education has become a marketing commodity, a multi-million dollar business. There has been a shift of education from social good to a marketable commodity. In this context, foreign universities are trying to have a share of the Indian educational market. Fourthly, it is necessary to raise the quality and standards of Indian education and make it globally competitive, locally relevant and enable it to offer a marketing paradigm appropriate for developing societies. Fifthly, national and global competition may create problems of the survival of weaker universities and colleges. Sixthly, support for the education of weaker sections and disadvantaged classes, particularly women, is lacking and the challenge to the marginalized, and deprived in the education system is enormous. Finally, the unit cost of traditional education, particularly of professional education, is high and has gone out of reach of the Indian middle and lower classes. Education should be made accessible to them to uphold socio-economic equity and justice.

The problems of the Indian education system relate to access, equity, number, relevance, quality and resource crunch. Although, India has the second biggest higher education system, the number of students is about 11 per cent of the relevant age group of 18–23 years. The average access ratio of developed countries is about 47 per cent, and in India the access parameter is less than one-sixth of that of developed countries. There is high access in the case of developed countries, for instance, 59 per cent in the US, 54 per cent in Canada, 33 per cent in Israel, 30 per cent in Germany, 29 per cent in Japan and 22 per cent in the UK.

There are wide regional disparities in the access parameter of higher education among states in India. As against 11 per cent of all India average, the Gross Enrolment Ratio (GER) is lower in the states of Arunachal Pradesh, Bihar, Madhya Pradesh, Meghalaya, Mizoram, Rajasthan, Sikkim, Tripura and Jharkhand. A UGC-sponsored study made by Sachidand Sinha (2007) revealed that out of 584 districts in the country about 373 districts had the GER lower than the national average. Of the total educationally backward districts, about 3 per cent had the GER less than 3 per cent. In 21 per cent of the districts, it varies between 3 per cent to 6 per cent, in 38 per cent of the districts between 6 per cent to 9 per cent and in the remaining 37 per cent of the districts, it varies between 9 per cent to 12 per cent.

There are significant intergroup disparities in access to higher education. The NSS data for 2004–05 reveals that the enrolment being 6.73 per cent and 19.80 per cent for the rural and urban areas, respectively. It shows that the GER in urban areas being three times higher compared to rural areas. Intercaste/tribe disparities are the most prominent. The GER among SCs was 6.30 per cent, among STs 6.33 per cent and among OBCs 8.50 per cent.

There are wide gender disparities in terms of the access to higher education. The access is generally lower for girls (9.11 per cent) as compared to boys (12.42 per cent). As against the overall average of 9.11 per cent, the GER among girls was 4.76 per cent, 4.43 per cent and 6.60 per cent, respectively, for ST, SC and OBC girls.

Also there are perceivable differences in enrolment among the poor and non-poor. The GER for the poor was 2.21 per cent as against 12.36 per cent for the non-poor. In the rural and urban areas, the GER for the poor stood at 1.40 per cent and 4 per cent, respectively, which was quiet low compared with 7.12 per cent and 27.15 per cent for the nonpoor, respectively.

The major constraints to access and equity of higher education in India are poverty— leading to high dropout rates, lack of easy access, low status of women, lack of implementation of existing programmes, inadequate utilization of existing resources, financial constraints and lack of political will.

The growth of higher education institutions has not kept pace with the growth of enrolments. In 2009–10, the total number of students enrolled in the formal system of higher education has been reported at 136.42 lakhs. This enrolment translates into a GER of 12.9 per cent. The world average of the GER is 26.7 per cent, the average of developed countries is 57.7 per cent and that of developing is 13 per cent. For raising the GER, many more universities and colleges need to be opened.

30.4.1 Quality and Excellence in Higher Education

The quality and excellence of higher education institutions are promoted by the UGC through grant-giving mechanisms and grants are provided to those who meet the minimum standard. The National Assessment and Accreditation Council is constantly involved in the quality assessment of universities and colleges. The quality of education can be evaluated with the helps of parameters or indicators. The quality gaps and the factors associated with quality in universities and colleges are presented in Table 30.6.

The quality of higher education is critically incumbent on the physical infrastructure, number and quality of teachers, and academic governance.

For promotion of quality and excellence, Eleventh Five Year Plan proposed the policy of improving physical infrastructure and the availability of adequate and qualified faculty. The universities and colleges face serious problems related to the availability of faculty. The sample data collected by the UGC indicate that about one-third of the university faculty is ad hoc/temporary and on contract. The study done by the Sixth Pay Commission for universities and colleges shows a very depressing scenario for all positions (see Table 30.7).

TABLE 30.6 Quality Gap—Factors Associated with Quality

Source: Qamar Furqan (2007), Quality and Excellence in Higher Education Study Sponsored by the UGC, New Delhi.

As is evident from Table 30.7, the overall level of vacant positions in state universities is 58 per cent. As around 90 per cent of students in university departments are enrolled in state universities, such a high incidence of vacant positions is making a damaging effect on both the quantity and quality of teaching and research in universities. The situation in colleges is far more distressing. As many as 52 per cent of the vacancies at the lecturer level and 42 per cent at the level of readers are lying unfilled. The shortage of teachers has led to the employment of part-time or ad hoc teachers. In all types of universities, the ratio of part-time teachers to regular teachers is 0.24 and in state universities, it is 0.33 and in colleges it is 0.38.

The Eleventh Five-Year Plan recognized the faculty problem and initiated policy measures of both short- and medium-term nature. The short-term measures include the increase in the retirement age up to 65 and the removal of restrictions on the recruitment of faculty. The medium-term measures include the increase in the number of research fellowships for M.Phil., Ph.D. and post-doctoral programmes. The Pay Review Committee recommended an improved salary structure and service conditions for attracting talent in the teaching profession.

TABLE 30.7 Vacant Positions of Teachers in 2007–08

Source: Study Sponsored by the Sixth Pay Commission for University and College Teachers, UGC, 2008.

The excellence may not be enhanced without quality education in universities and colleges. The focus is on improving the academic and physical infrastructure for quality improvement. Another aspect related to improving the quality is academic reform, including changes in the admission procedure of various courses, modification in assessment and examination methods, switch over from the annual to semester system, acceptance of the grade and credit system and teachers’ assessment.

The important initiative in the Eleventh Five Year Plan for reforms in higher education include reforms of affiliated systems, preparing a framework for public-private partnerships, rationalization of fee structures, regulation of deemed universities, regulatory framework for collaboration by universities and colleges with institutions in other countries with respect to dual-degree arrangements, sharing of courses, credit transfers and sharing of teachers, etc. Accordingly, the UGC has set up various committees on these reforms. The Yash Pal Committee prepared a framework and Tapas Mazumdar’s Committee recommended the need to set up institutions for research, policy and monitoring of higher education.

In the globalized world, the state-protected educational system cannot withstand the pressure of competition. A new policy initiative should be taken because of the following reasons. First, the economic return of higher education is less than that of primary education. Secondly, the private returns on higher education are greater than the social return. Thirdly, the state funding of higher education is insufficient. Finally, the private sector benefits the most from higher education; it is reasonable to expect that the private sector should make decisive contributions. Universities should generate their own resources to a large extent. With innovative schemes like launching courses for foreign students, obtaining donations from philanthropists, research grants from industries, taking up international- and government-funded R&D projects, funded projects from the industry and other sources, alumni contributions and encouraging knowledge-based consultancy services at institutions.

30.4.2 Vision and Strategies of the UGC

Higher education is essential for the cultural, socio-economic and environmentally sustainable development of individuals, communities and nations. Higher education is essential for the survival and also it is a lifelong process. As the world is passing through a ‘knowledge revolution’, the four key principles—quality, access, equity and accountability— which have always been crucial in the development of higher education continue to be the guiding principles when planning for higher education for the 21st century.

India is recognized internationally as a nation that provides higher level of training to develop human skills. Owing to the globalization of job markets, the demand for Indian skill is rising. Moreover, the service sector, the fastest growing sector in Indian economy, requires trained human power at various levels. As the world demography is changing, and to take advantage of the change, we have to supply trained personnel at par with global standards. The student community in the rural, semiurban and urban areas wants to be a part of the new economic revolution. Proactive efforts are made to attract young members from the disadvantaged groups into the mainstream of higher education by devising well-designed and consistent remedial support, both at the academic and at the financial level.

The salient features of thrust areas of the Eighth Five Year plan (1992–97) were: (i) designing courses, joint funding in emerging areas of science and technology; (ii) quality improvement of education, including campus development; (iii) promotion of autonomous and academic staff colleges; (iv) national education testing and accreditation of universities and colleges; (v) strengthening of undergraduates and post-graduate education and research in colleges; (vi) quality improvement programmes; and (vii) adult education, continuing and distance education, media centres and management of higher education.

The thrust areas included during the Ninth Five Year Plan (1997–2002) were the following: (i) infrastructural development of universities and colleges; (ii) relevance of vocational education, revision of curriculum, orientation of teachers, strengthening of emerging areas and innovative programmes, value education; (iii) promotion of excellence and quality; (iv) special assistance programmes, research awards, cultural exchange programmes and networking of universities; (v) inter-university centres, accreditation of universities and colleges; (vi) equity-special schemes for women, SCs/STs and differently-abled persons; (vii) resource mobilization and state control of higher education; and (viii) computers for universities and colleges and technology course for women.

Various schemes that would be operationalized during the Tenth Five Year Plan (2002–07) are—(i) general development of universities and colleges; (ii) enhanced access and equity; (iii) promotion of relevant education; (iv) quality and excellence; and (v) strengthening of research.

30.4.3 GATS and Higher Education

Education is a big and expanding service industry. The WTO estimated that on the threshold of the 21st century, global public spending on education tops $1 trillion (Rs 4,700,000). This represents the cost of over 50 million teachers, one billion pupils and hundreds and thousands of educational institutions. As a part of the WTO General Agreement on Trade in Service (GATS), the liberalization of trade in services is initiated. The GATS has classified services in 12 sectors including education. International trade in higher education in 1995 was estimated at $27 billion. Between 1995 and 2000, it has gone up one-and-a-half times. Globally, the number of students going to various countries for higher education is two million annually. However, the Indian market share of the global education market is a meager 0.5 per cent. The number of inbound students to India is only 12 per cent of the number of students going abroad for higher education. Currently, most of these students come from developing countries (the Middle east, South East and far east, and Africa). Most of them opt for traditional graduate programmes and only a few professional courses. Most of these universities have inadequate infrastructure in comparison with global competitors.

The mammoth structure of the Indian higher education is well rooted across the length and breadth of the country. In India, education is a social and economic infrastructure. The Indian education system, particularly higher education, falls under the GATS web. Indian education institutions are following all the four modes of trade, namely cross-border supply, consumption abroad, commercial presence and individual presence. The Indian higher education system is now globally accepted as a quality education service, that is, consumption abroad through the presence of Indian students in foreign universities, cross-border supply through teachers working abroad and commercial presence through setting up of colleges and universities in other countries. In a way, India has partially privatized higher education by initiating non-grant teaching programmes and a dual-fees structure for professional subjects.

The GATS would open India’s education sector to foreign universities. India will have to respond in a proactive manner by adopting an open and flexible structure, allowing the students to combine traditional, open and skill-oriented education and allowing private providers. We have to export education, and government rules and regulations will have to be more conducive for easy export. The GATs is a challenge, which is to be met without compromising on the considerations of equity and access to Indian students.

30.4.4 A New Initiative of UGC in the Tenth Plan: Promotion of Indian Higher Education Abroad

In the context of globalization, it is now imperative for Indian campuses to have a multicultural and multi-ethnic ambiance. A proper mix of international students is felt necessary to ensure holistic education to the top universities of the country. The government has already allowed higher education institutions to have 15 per cent of the seats filled up by international students. However, the number of foreign students in Indian campuses is on a decline. According to the Association of Indian Universities, the number of foreign students in India has declined from 13,707 in 1993–94 to 8,145 in 2001–02. On the contrary, in the US, there are 583,000 students, 4.3 per cent of the total enrolment in universities in the US. This brings in $11.95 billion into the economy of the US.

India has a huge global opportunity in the education sector. However, students from developing economies are being lured by the aggressive marketing done by many developed countries. India is losing out due to a lack of coordinated effort in this direction. It is in this context that the UGC has launched a new initiative for the promotion of Indian higher education abroad, a clear vision for internationalization of higher education.

30.4.5 New Reforms in Higher Education

The National Knowledge Commission (2007) and the Yash Pal Committee [Committee to advise on the Renovation and Rejuvenation of Higher Education (2009)] have dealt with various issues affecting the higher education system in the country and both have suggested a definite framework for improvement by way of institutional as well as policy reforms. One of the main recommendations is the establishment of an overall regulatory body, viz., the National Commission on Higher Education and Research (NCHER), which will replace the UGC, the AICTE and the National Council for Teacher’s Training. The other reforms suggested are wide ranging from accreditation of higher education institutions to curbing malpractices to entry of foreign educational providers.

30.4.6 Foreign Educational Institution Bill

The Foreign Educational Institutions (Regulation of Entry and Operations) Bill, 2010 has created a controversy, which would allow foreign educational providers to set up campuses in India and offer degree. A bill to this effect was first introduced in the Rajya Sabha in August 1995. The new bill, introduced in the Lok Sabha on 3 May 2010 aimed at regulating the entry, operations and standards of foreign education providers, providing quality assurance, preventing commercialization, protecting students from fly-by-right operators and promoting educational tourism. The bill allows educational providers abroad to set up campuses here and give degrees. With 160,000 Indians studying abroad, spending $4 billion a year in fee, the bill should help reverse both. Foreign operators to invest at least 51 per cent of the total capital expenditure needed to establish the institution in India. Such institutions shall be granted the deemed university status.

Foreign education providers already have a presence in India. In 2008, around 140 Indian institutions and 150 foreign education providers were engaged in academic collaborations. Of the 150 foreign providers, 90 have the university status and 20 have the college status. There were 225 collaborations, delivering 665 programmes, 168 in Management, 144 on Engineering and Technology and 132 on Hotel Management. Incidentally, these foreign collaborations are highly concentrated in Maharashtra and Delhi, followed by Tamil Nadu.

The bill, a radical move of permitting foreign universities, is far more controversial. It is unlikely to stop either brain drain or attracting top-notch foreign universities. Only substandard universities will be attracted and not Oxford, Cambridge, Harvard, MIT, Yale, etc. The bill is a sell-out of higher education in India. The National Knowledge Commission and Yash Pal Committee recommendations called for the creation of 1,500 universities with freedom to innovate and offer quality higher education.

30.4.7 Establishment of the NCHER

The bill for the establishment of the NCHER implies that the NCHER is not a regulatory or controlling or licensing or inspection body. It is intended to evolve norms and standards for various aspects of higher education, including assessment and accreditation. Existing regulatory bodies like the UGC, AICTE and NTE will consequently stand abolished. A unique function of the NCHER is the identification of academic administrators of national standing who are eligible for appointment as Vice-Chancellors or heads of central educational institutions. The members of the NCHER would be selected by a committee comprising the prime minister, leader of the opposition and speaker of the Lok Sabha and will be free of control by any ministry and will be responsible only to the parliament. Some states oppose the key clauses that they see as the violation of the federal principle. However, for the quality and health of higher educational institutions, we need, bold, imaginative and innovative steps and the NCHER will be a good start.

References

Biswas, A. and Agarwal, S. P. (1994). Development of Education in India. New Delhi: Concept.

Chadha, G. K., Bhushan, S. and Muralidhar (2008). Teachers in Universities and Colleges—Availability and Service Conditions. Study Sponsored by UGC. New Delhi: UGC.

Dayal, B. (1955). Development of Modern Education in India. Bombay: Orient Longman.

Drez, J. and Sen, A. (1997). India: Economic Development and Social Opportunity. OUP, New Delhi.

Government of India (1965). University Education. New Delhi: Ministry of Education.

Government of India (1968). National Policy on Education 1968. New Delhi: Ministry of Education.

Government of India (1979). Draft National Policy on Education. New Delhi: Ministry of Education and Social Welfare.

Government of India (1985). Challenge of Education——A Policy Perspective. New Delhi: Ministry of Education. Government of India (1986). National Policy on Education. New Delhi: Department of Education, Ministry of Human Resource Development.

Government of India (1986). Programme of Action, National Policy on Education. New Delhi: Department of Education, Ministry of Human Resource Development.

Government of India (1990). Reports of the Education Commission 1964–69. New Delhi: NCERT. Government of India (1950). Reports of the University Education Commission 1948–49. New Delhi: Ministry of Education.

Government of India (2007). National Knowledge Commission, Reports of the Nation 2006. New Delhi: Government of India.

Kaur, K. (2003). Higher Education in India (1781–2003). New Delhi: UGC.

Mukerji, S. N. (1953). History of Education in India. Vadodara: Acharya Book Depot.

Mukerji, S. N. (1976). Education in India: Today and Tomorrow. Vadodara: Acharya Book Depot. Nullah, S. and Naik, J. P. (1974). A Student’s History of Education in India 1800–1973.

Raza, M. (ed.). (1991). Higher Education in India. Retrospect and Prospects. New Delhi: AIU.

Sharma, K. A. (2003). 50years of UGC. New Delhi: UGC.

Sharma, S. (2002). History and Development of Higher Education in India. New Delhi: Sarup & Sons. Thakkur, D. and Thakkur, D. N. (1999). New Education Policy. New Delhi: Deep and Deep.

Thorat, S. (2009). Emerging Issues in Higher Education: approach, Strategy and Action Plan. Indian Economic Journal 57 (1) April-June.

UGC. Annual Reports of Various years from 2000–01 to 2005–06. New Delhi: UGC.

UGC (1978). Development of Higher Education India: A Policy Frame. New Delhi: UGC.

UGC (2002). Xthplan of UGC. New Delhi: UGC.

UGC (2003). Higher Education in India: Issues, Concerns and New Dimensions. New Delhi: UGC.

World Bank (2000). Higher Education in India, Perils and Promise. Washington D.C., World Bank.