1.2 Masterplanning

The idea of the planned campus is, in many ways, at the heart of the development of the idea of the university. Although many contemporary institutions bear the marks of uncoordinated developments in relation to periods of rapid growth in research and student numbers, most now recognise the need for strategic planning of their estates. Competition in terms of reputation, the pursuit of research funding and student applications means that universities in the UK and in many other countries have been investing heavily in their built environment. This investment has provided a major opportunity for universities to respond to changes in pedagogy and research practice, to embrace the consequences of the information revolution and to address environmental challenges and the desire for greater public engagement.

Architecture and design have responded to these challenges with notable enthusiasm, producing buildings of distinction that make an important contribution to the public realm and often compete with the best new architecture nationally.

The central challenge is whether, given the rapidity of expansion and pressure on budgets, and with the rate of change being so fast, planning is sufficiently robust to ensure that some of the great university buildings over the last two centuries are matched in the future.

This chapter sets out the key factors that lie behind the masterplanning process and how it fits within wider institutional governance.

Planning the Relationship between Function and Form

The idea of planning the relationship between function and form dates back to medieval European universities which, as for example in the case of Oxford and Cambridge, brought together the classic combination of teaching, residence, dining hall and chapel around a central open space. This model was adapted to the American environment from the early colonial days18 where the monastic model gave way to a ‘campus’ of separate but related and planned buildings, more open to the outside world. Harvard, Yale, William and Mary, Princeton (the first university to which the term ‘campus’ was applied), and the University of Virginia in the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries laid the groundwork for future conceptions of the university’s estate. Joseph Jacques Ramée’s 1813 plan for Union College in Schenectady, New York, was the first comprehensively planned campus in the USA,19 since much used as a point of reference, not least by Thomas Jefferson in the University of Virginia soon afterwards (1817–26).

In Britain, the expansion beyond the medieval universities in England and Scotland during the 19th and early 20th centuries produced a variety of physical responses, determined not least by location. To what extent does the campus of today reflect previous attempts at masterplanning? The picture is mixed. In London, where space was constrained, the new 19th-century institutions such as UCL, King’s College or Queen Mary were characterised by one particularly impressive new building – by William Wilkins, Robert Smirke and E.R. Robson respectively.

Example

University of York UK

The University of York, UK founded in 1963, is a good example of a planned university (designed by RMJM) adapting its founding principles to future expansion as the university grew in stature and size. Its expansion on to a new site at Heslington East in the early 21st century has been guided by a masterplanning process. The university has aimed to create a single campus and maintain a high-quality rural landscape setting in a largely car-free environment, and ‘the strong integration of activities – research, teaching, business, social, sporting, leisure and residential. We intend the campus to be secure, distinctive and publicly accessible.’ University of York, Estates Strategy, 2013–20

Figure 1.1

These developments found echoes in continental Europe, for example the universities of Graz or Lund.20 Outside London, there has been considerable variety of experience, with what became the great ‘red-brick’ institutions21 often planned on an impressive scale – Alfred and Paul Waterhouse at Manchester in the 1870s, for example, or Birmingham’s grand collection of buildings by Aston Webb and others from 1900.

By the 1960s, the wish to expand meant that new universities were created, taking the number of UK institutions from 22 to 46 and the number of students from 108,000 in 1960 to 228,000 in 1970. The new campus universities – Sussex, York, University of East Anglia, Lancaster, Essex, Warwick and Kent – were all created between 1961 and 1965, each to a plan.22 Sussex, designed by Basil Spence, has the only Grade I listed buildings from that period.

In other longer-established institutions, expansion led to perhaps the least happy period for university architecture, with poorly designed buildings, especially for expanding research and teaching in science, springing up. Oxford and Cambridge were not exempt from these challenges, with each having science areas of pedestrian and muddled design.

Subsequent expansion, particularly by giving university status to former polytechnics and other institutions and, especially from 1997 expanding the number of students admitted, has dwarfed earlier growth and thrown the need for adequate planning into sharp relief. By 2013/14, the total student population at over 140 university institutions had risen to 2,299,355.23 There was an increase of 32.5% in postgraduates and 14% in undergraduates since 2000/01, with a considerable increase in those coming from overseas. This has been matched by unprecedented capital expenditure. Between 1997 and 2011, UK higher education institutions spent £27.5 billion,24 generated through a number of financial sources. Part of this was based on external borrowing, part on internal surpluses and part on direct grants for teaching and research infrastructure from the funding councils.

In many other countries in the developed world, universities have also expanded greatly and produce regularly updated masterplans. The USA and Australia abound with examples of institutions planning expansion carefully, but so too do countries in Latin America and the Far East, notably China.

The Process of Masterplanning

In surveying these diverse examples, current masterplanning of the university estate may be seen as being driven, therefore, by ten principal factors.

- 1. The increase in competition among universities, where buildings and facilities are given new prominence in the search for a successful market “brand”, has increasingly led universities to seek out the best architects to deliver high-quality and innovative buildings.

- 2. The increase in student numbers and associated changes in funding – in the UK, for example, fees charged directly to students both from within (most of) the country and from overseas – has given fresh prominence to the idea of student satisfaction. This includes not only high-quality teaching spaces but also libraries, facilities for sport and well-designed common learning spaces and good residential accommodation.

- 3. Investment in research has greatly expanded the need for new build in the leading universities, including major scientific collaborations with external bodies.

- 4. In both teaching and research, the estate needs to be adaptable to future changes in pedagogy and research practice, not least in information technology.

- 5. Specific provision for ‘growth’ subjects, such as business and management, law, or medicine and the life sciences.

- 6. A greater sense of public engagement within local communities, not least through museums and galleries owned by universities and through public art.

- 7. The need to ensure compliance and sustainability, and adequate future maintenance.

- 8. The need to ensure efficient space utilisation to help underpin financial performance.

- 9. The development of many universities as global institutions, attracting overseas students but also increasingly building overseas campuses, often with local partners.

- 10. The need to consider the residential estate and the extent to which external providers reduce the need for universities to engage directly in provision.

We shall discuss the importance of masterplanning within institutions below, but it is also of vital importance with respect to a number of external bodies. These include external lenders, who have financed much recent expansion; and, though their significance has been reduced of late as universities have increasingly become masters of their own fates, external funding bodies (such as the HEFCE, Higher Education Funding Council for England, and its Scottish and Welsh equivalents in the UK) in giving capital grants and applying governmental policy on sustainability. Such was the case, for example, with the CIF (Capital Investment Fund) grants allocated to English universities in the first decade of this century, where demonstration of masterplanning and effective management of the estate was essential.

The Local Context

Example

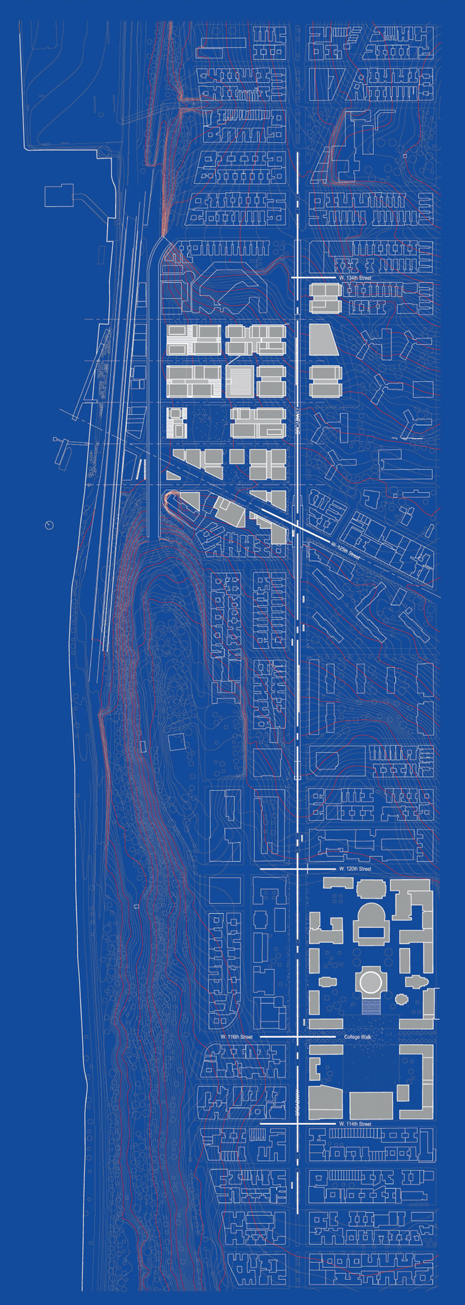

Columbia University Masterplan Renzo Piano

Figure 1.2

Columbia University provides a good example of both masterplanning underpinning the foundation and expansion of a distinguished university and also the perils of further expansion in a local urban environment. Originally founded in 1754, the Morningside Heights campus in New York was designed along Beaux-Arts principles by McKim, Mead and White, following Seth Low’s late 19th-century vision of a university campus where all disciplines could be taught in one place. The university also owns extensive residential property for staff and graduate students in the vicinity, as well as two dozen undergraduate halls of residence. Controversy was sparked in 2002 when a new $7 billion masterplan for the Manhattanville campus in West Harlem by Renzo Piano and Skidmore, Owings & Merrill proposed taking over new land. Although eventually approved in 2009, there was considerable and sustained local opposition by residents and others. The first buildings have now been completed.

Local planning authorities also need to be reassured that individual planning applications are both set within a general institutional plan and have been considered in relation to local planning frameworks. Within this context, too, the importance and sometimes protected status of historic buildings can have a major effect on the planning process. Nor should the possibility of local opposition to new development be underestimated, for the urban campus, neighbours, landowners and adjacent businesses and institutions vie for attention and land. On a greenfield campus, similar concerns overlap and extend to include ecology, landscape and views, and greenbelt policy. Hence the question of when to enter into public engagement on the masterplan needs to be considered, particularly around commercial sensitivity when leading to disposals or acquisitions, through either growth or consolidation. Too soon, with too much on the table can confuse; too late then the only option is to object rather than influence.

As an independent major institution the university can sit uncomfortably between central and local government. Add to that wider European initiatives and potential for funding partnerships and the picture is complex and changing. It is against this background that the local picture for each university unfolds. The relationship between university institution and local authority in the UK varies greatly. Some older universities have a proud heritage of stewardship, evidenced through the commissioning of high-quality buildings, although some have not always maintained this path. The newer UK universities often enjoy a much closer relationship with their local authorities, born out of their technical college and polytechnic heritage, which had strong links to local education delivery.

Universities can, of course, be important partners in regional growth and regeneration, and often the university masterplan may be seen in a wider context.

As Charles Landry observed, ‘The city is an interconnected whole. It cannot be viewed as merely a series of elements, although each element is important in its own right. When we consider a constituent part we cannot ignore its relation to the rest.’25 For example, in London, the University of the Arts relocation, at a cost of £145 million, has been part of a vast scheme for urban regeneration at King’s Cross/St Pancras, which also includes the £650 million Francis Crick Institute for biomedicine. At the Olympic Park in Stratford, planning a higher education presence is very much part of a masterplan to integrate cultural, residential and economic activity. Similarly, in Manchester, the University of Manchester, Manchester Metropolitan University and the city planning authority are working closely together on an integrated regeneration of a substantial chunk of the central city.

As with all future planning there is a dichotomy, balancing private benefit and the public good. For a university, which has clear public benefit, there are also private interests and needs. In an ever-more competitive higher education environment, the concerns of privacy and commercial confidentiality, often motivated by competitive advantage, need to be tempered with public good. When considering long-term aspirations and impact on the campus, its planned future and the options available, a period of private considered reflection is needed before telling the wider world. Working in isolation, while simpler, will give little opportunity for support from key external bodies. So the question is not whether to engage or not, but when. This sits alongside the question of what is the nature and purpose of the engagement. And is it a longer-term relationship and not one born out of short-term aims?

It is a network of interrelated interests, not simply a pyramid from national to local that informs the strategic picture for an individual university. This network brings complexity, but it also puts a greater burden on the clarity of the masterplanning project from inception through to completion. However, by involving others there is potential to unlock opportunities not available by acting alone. With pressure continuing on efficiencies, finding the right partners helps, for example, to exploit space for the full year. Partners extend to NHS Trusts, and beyond to charitable foundations such as The Wellcome Trust and Sainsbury Family Trusts; to private organisations, for conferences, sports and wider events; and to international partners, whether private enterprise or arts and cultural institutions, with many universities holding rare and designated collections.

Estates Masterplanning and Corporate Planning

The way in which these pressures are handled is determined to some degree by type of institution. It is worth recalling that the balance of research versus teaching varies considerably (the proportion of institutional income that derives from research, for example, varies within multi-faculty UK universities from around 70% to almost zero); that the size of institutions varies greatly; and that location, history and rate of growth bring different flavours to the masterplanning process.

Central to how the process proceeds is the link with institutional vision and strategy. Most universities publish a corporate plan, revised periodically, in which investment in estates and facilities is explicitly recognised and is also implicit in wider targets for growth. Much of the thinking around estates development is long-term and therefore the masterplan has a significant role to play in persuading senior members of the university – Vice Chancellors and their deputies, Deans and Heads of Schools – that thinking carefully about

Example

Crick Institute

The Crick Institute in London, due to open in 2016, is a good example of the way in which estates development must adapt to changing university research practices. It is also an important element in the wider commercially driven masterplan for regeneration in the King’s Cross area. The principal partners comprise major universities (UCL, King’s College London and Imperial College London) and the Medical Research Council, Cancer Research UK and the Wellcome Trust. Architects HOK and PLP Architecture have designed a notably innovative building. Total investment is in the region of £650 million and, when completed, it will employ 1,500 staff of whom 1,250 are scientists. The location near major transport hubs, including the Eurostar terminal at St Pancras and many other scientific, educational and cultural buildings (for example, the British Library, King’s Place and the University of the Arts London) give the project a head start.

Whether this building embraces its context by becoming a welcoming public presence in the area in the way the UAL building does further to the north will be demonstrated when it opens. While the public will be able to see into its large central atrium, it will need a strong outreach programme to encourage interaction with the public.

Figures 1.3 and 1.4

space, understanding the importance of good design and ensuring future flexibility, and budgeting appropriately for the estate, is a central part of strategy.

Certainly there is ample evidence that this is being taken on board.26 The University of Oxford, for example, has recent, or soon to be completed, buildings by major international practices, including, among others, Zaha Hadid, Herzog & de Meuron, Rafael Viñoly Architects, WilkinsonEyre Architects, Rick Mather Architects and Dixon Jones.27 This approach is reflected in the award of architectural prizes to university schemes – for example, the Architects’ Journal28 records that four of the top 20 UK clients winning RIBA prizes in the last ten years were universities, and that the RIBA Client of the Year was Manchester Metropolitan University. It also reflects an international trend towards the appointment of ‘star’ architects to bring a particular gloss to image and reputation, though as the examples quoted above show this is not an entirely novel phenomenon.

If masterplanning is to lead to results on the ground, integration with financial planning is essential. Two aspects are significant:

- 1. Full engagement in developing business cases for investment with the academic community who generate the activity.

- 2. Making sure that estates planning is fully integrated with the financial management of the university, with an agreed approach to the development of surpluses and external financing.

The detailed implementation of a plan depends not only on reacting to internal aspiration but also helping to shape that aspiration by the application of good practice from elsewhere. This may include the links between space and pedagogy, and the ways in which students behave and learn on the campus; for example, in relation to developments in information technology.

Equally, a good masterplan also helps the institution to manage compliance and maintenance and develop robust targets for environmental performance (as in the example of Lancaster University, which developed a specific masterplan for what one might call the nuts and bolts of services and environmental performance).

Project Governance

Project Set-Up, Management and Briefing

The normal proposition is that the estates and property team within a university commission a masterplan from external consultants. Rather like a brief for a single capital project, the masterplan will need to be defined in scope. A balance needs to be struck between being specific and limiting the outcomes versus being open to unexpected solutions emerging during the process. The scope of a masterplan can vary hugely, ranging from the development frameworks for major new districts (for example, north-west Cambridge), to supporting organisational change, to spatial capacity studies that increase density in discreet parts of the campus.

Figure 1.5

The University of Oxford: The Blavatnik School of Government by Herzog & de Meuron sits in the delicate historic context of the Radcliffe Infirmary quarter redevelopment. The long double-glazed window above the entrance frames the view across to the Neo-Classical Oxford University Press.

The university will know the critical areas within a physical campus and organisationally that need to be addressed and resolved through the masterplan process. These should be clearly stated.

The brief

A succinct briefing paper developed by the ‘project board’ (see below) setting out the concerns, keeping in mind the ten principal factors (see page 13) and setting out the vision for the institution. The vision should state the ambition of the study, for example:

- • To complete the campus.

- • To improve the sense of place.

- • To increase density, for example more research space or greater intensity in the use of teaching and learning spaces.

- • To overcome poor connectivity.

In addition, an outline of the scope should be stated and should include:

- • Timescale for the study to be completed and what is the plan period, for example 15–20 years?

- • An explanation of engagement required within and external to the university.

- • How will the masterplan be reviewed, for example every 5+ years?

- • How will the masterplan accommodate change?

- • Does the masterplan need to be approved or adopted by the planning authority?

Continuity with the project briefs

There should be a connection into project delivery, including:

- • How the masterplan should be communicated to individual project teams and what aspects can be delivered in individual projects, whether major or minor.

- • Explain expectations about phasing, decant and whether there is flexibility over phasing.

- • Infrastructure (often identified separately to capital works).

- • Impact on facilities management and running costs.

The team

A masterplanner does not come in one size or shape but may have an architectural, urban design, landscape or planning background. How a team is formed and responsibility for coordinating multiple inputs needs to be considered. Typically, there is a single source appointment and an architect leading the team brings a wider educational focus, rather than, say, a town planner or urban designer. The choice of lead will depend on the type of study required. Project management may be a combination of internal or external and benefits come with each. There is accountability from an external consultant, who is dedicated to this project, which avoids the complexity of ongoing day-to-day distractions for an internal project manager, though of course many universities have capable and strong project management skills within existing teams.

Cost, viability and value

A quantity surveyor normally covers this; however, a masterplan study will also often include valuation and potential acquisition or disposal of sites. A valuer may be involved and universities often retain these separately. The costing of a masterplan against the likely timescale is critical. On completion of the masterplan, which plans over, say, a 15–20 year period, there will be a need to consider how to make adjustments for changes in market conditions.

Engineering

Services, infrastructure, highways, energy use and many more are concerns for a masterplan. Note, however, that a masterplan is informed by detail, yet must not get bogged down in it. Keeping the inputs and recommendations at a high level distinguishes the study as a masterplan, rather than as a series of feasibility studies for the implementation of projects.

The project board: engagement, management and decision-making

To ensure the masterplan develops and delivers the aims of the university strategic plan, it is vital that the university develops a clear strategy for the leadership and development of the masterplan, as there is always much to cover, often to a tight timescale.

Responsibility for decision-making

This is the project champion, lead or sponsor. He or she will ultimately be responsible for signing-off the brief, signing-off on the options to be explored and reporting to the university governance. The person may well be a board member or a member of the executive. They will have ownership of the budget, have got buy-in to the aims and objectives, and fully understand the vision to be achieved.

Example

Queen Mary University of London

Queen Mary University of London, founded in the 1880s and a member of the Russell Group of research-intensive universities, has pursued a policy of sharp growth in both student numbers and research over the last 30 years. Located on tight urban sites in inner London, the 1985 masterplan for the main campus (top right) has been used to guide each new building and by 2015 almost all of the buildings envisaged in that plan have been brought to fruition. Two of the most recent – a new Humanities Building (£25 million) and a new Graduate Centre (£39 million), both by WilkinsonEyre Architects – were the product of careful development of business plans with the academic schools and part of an integrated approach to capital planning. Along with other buildings, for example a student village by Feilden Clegg Bradley Studios and a new medical school building by Alsop Architects, good architecture has helped to redefine the institution, both internally and externally.

Figures 1.6 and 1.7

Figures 1.8 and 1.9

Participation in decision-making

This may well be a ‘project board’, involving estates and property, academic, student and professional services representation: a sounding board for the project sponsor, made up of representatives of the wider institution. Where key partners are involved in the masterplanning, then they are likely to be represented here. It is possible to have third-party representation at this level who does not have a direct interest in the project. Their role would be to challenge and support while bringing new skills to the existing group. This could be via peer review from another institution, an independent advisor or RIBA

Design Advisors.

Consultation

Wider consultation should be informed by the Gunning Principles:29

- • Consultation must take place when the proposal is still at a formative stage.

- • Sufficient reasons must be put forward for the proposal to allow for intelligent and timely consideration and response.

- • The product of consultation must be conscientiously taken into account.

There will be numerous other considerations. How does the board consult at a wider level? Will the university want their consultant team to manage this? Will the project board members lead this engagement through workshops with a wider group of academics, professional services and students? Does the representation reflect current faculty and wider institutional lines, or could this be organised as a delivery group, responsible for ensuring the masterplan covers all relevant aspects of the university’s vision? For example, the board has a role in disseminating, commenting on scope and preferred options and chairing sounding boards for specific aspects of the developing proposals.

Informing those affected

How will this be carried out? What should be said at each stage? Social media and online have been successfully used by institutions to inform wide groups. Representative members of the group who are participating in decisions should also be responsible for disseminating and ensuring representation of areas of interest. For example, the Student Union representative would need to work with a wider group, consult them and discuss and debate responses to particular challenges thrown up by the masterplan study.

Inputs and Outputs

For the masterplanner, there are a number of baseline pieces of information which are either essential or informative in creating the brief. These form the hard data from which to develop the masterplan. Part 3 discusses the process of brief development. The table here provides an initial checklist of inputs and outputs.

Baseline data required for a masterplan

The following list provides some guidance to the background needed:

The academic ambition

- • Corporate plan and detailed academic plans, as the aim of the masterplan is to align the academic and corporate vision with the estates strategy.

The historical context

- • Historical context: importance of tradition and heritage and including current and past masterplans.

The existing estate

- • The physical estate; plans of buildings, sites and infrastructure: accurate, up-to-date survey or asset plans which are linked to the space database.

- • Space Utilisation Survey (SUS): combining intensity and frequency of use, normally needed in the UK for the annual Estates Management Statistics (EMS) returns for each university.

- • Building condition, for example rating buildings on a scale from A–D (A = new, D = poor condition).

- • Surveys including topographical and ownership (for example, in the UK Land Registry plans). Not just to understand ownership and tenure, but to consider whether acquisition on non-contiguous parts of the campus could be assembled to create a better campus over the longer term.

- • Electronic management systems, rather than simply electronic record files. This is a developing area, known as ‘Geo-Spatial BIM’, a hybrid of GIS data and Building Information Modelling.30

- • Ongoing projects: work currently being undertaken on site, from small refurbishments, summer works, infrastructure and agreed and budgeted works for the immediate future.

Infrastructure and sustainability

- • Servicing and energy use, including EPC/DEC certificates for all buildings.

- • Water, waste, recycling, deliveries and logistics. Where and how do these happen?

- • Sustainability: in the UK the Carbon Reduction Commitment (CRC) defines overall targets for buildings and wider use, such as purchasing. However, some are being much bolder: for example, the University of California has pledged to become carbon neutral by 2025, becoming the first major university to accomplish this.31

Outputs

The range of outputs from the masterplanning process may include the following:

Spatial strategy

- • Spatial strategy, size of estate, uses and needs, including teaching and learning, research, public engagement and professional services space needs.

- • Space typologies and standards, for example cellular, open (sqm/person per space type).

- • An assessment of space in relation to assumptions on growth, business cases and external funding opportunities.

- • Guide to space use/interfaces with internet learning.

Building and site planning

- • Commentary on existing buildings, and how far they are suitable for conversion and re-use, or need replacement.

- • An assessment of heritage assets.

- • Capacity for new build and expansion.

- • Ownership, boundaries and neighbours, and the potential for acquisition and disposal.

- • Townscape audit, connections, landscape, prioritised projects and improvements.

- • Routes, levels, highways, logistics and parking.

- • Public realm and public arts strategy.

- • Design codes to define critical principles which will define how new buildings and spaces should be designed. This could cover issues such as building uses and location, relationship to landscaping and external space, façade design, heights, circulation, ground floor uses, character and materials. How prescriptive these are will depend upon the circumstances of the site and the approach of the institution. Ambitions rather than rules may provide greater flexibility to tackle future change (as discussed earlier by Tom Kvan on pages 3–9).

Infrastructure and sustainability

- • Infrastructure: power, water, IT and other services.

- • Sustainability criteria and targets.

A completed masterplanning exercise, which reflects the future ambition of the institution and meets the aims of the vision developed through consultation, is clearly an asset for the institution and should be disseminated widely.

Typically there are several audiences for the masterplan, some requiring a non-technical guide to the masterplan, which excludes any commercially sensitive and confidential information, and then the full version is available for those who will work to implement the plan.

Conclusion

The ‘Idea of a University’ was a village with its priests. The ‘Idea of the Modern University’ was a town… ‘The idea of the Multiversity’ is a city of infinite variety…32

The university sector continues on a journey from inward ‘village’, through ‘ivory tower’ and the glorious isolation of the elite, towards the joint aims of broader access and raising achievement. This has meant huge growth in the sector, opening up higher education while to some degree maintaining an idea of retreat from normal life to reflect and grow through learning and research.

Universities, as complex institutions, increasingly play a crucial role in their local, national and international environments in terms of economic and cultural, as well as educational, leadership. This is the task for a masterplan: to plan for this change.