2.1

Teaching and Learning Spaces

Opinion

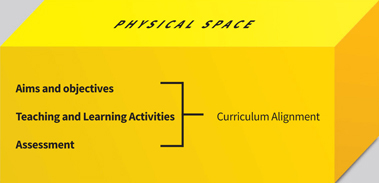

The aim of this introduction is to provide a perspective on the process of developing learning spaces in higher education. The development or redevelopment of learning spaces must be considered from an overall perspective of the intended curriculum experience and curriculum alignment. The core message is curriculum alignment: all physical learning spaces must always be analysed, evaluated and developed in order to align with a current or emerging curriculum.

An analogy is made between the development of technical devices and the development of learning spaces; software and hardware developers have to work together on a specific product in order to make it work. Curriculum developers (software developers) do not always coordinate well with developers of physical learning spaces (hardware developers) and as a consequence we all too often find a clear misalignment between emerging curricula and physical learning spaces. Many new buildings might have a modern shell but remain a ‘museum’ of old-time ideas about teaching and learning inside.

It is suggested here that the educational input into the very early stages of any project – the visionary briefing – is key: a creative, iterative briefing process led by educational experts, who have a central responsibility to articulate educational performance requirements of learning without going into design or technical issues too early.

Hardware and Software Developers: The Missing Interface

According to Biggs and Tang,1 curriculum alignment may be defined as the connection between all aims and learning objectives, teaching and learning activities and the assessment of an educational programme. The aim is to strive for maximum consistency throughout the system and clear objectives should state appropriate levels of understanding rather than report on topics to cover: teaching methods should be chosen on the basis that they lead to realisation of the objectives, and assessment tasks should be created on the basis that they address exactly what the objectives state that the learners should be learning.

What is lacking, though, from the conversation about curriculum alignment is the connection to physical and virtual learning spaces. What kinds of learning spaces are needed in order to implement a specific curriculum?

A traditional discipline-based curriculum is based mainly on lectures. This requires specific physical learning spaces, i.e. lecture halls. However, many universities are putting more emphasis

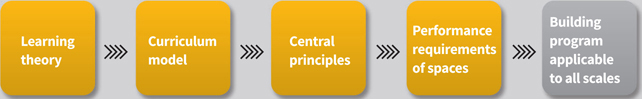

In different industries soft ware development typically works with ‘interface specifications’ which allow different developers to work on their part of the product independently. As long as every team sticks to the agreed interface definition, each separate part will fit together smoothly. Thinking about the interface also means understanding that complex systems can work well and still remain flexible.

What is oft en missing in developing physical learning spaces is the active collaboration between the soft ware and hardware developers.

on active learning and collaboration while the physical learning spaces supporting new curriculum ideas oft en remain as they were, based on ideas about teaching and learning as simple transfer of information.

Figure 2.1

Aligning curriculum with physical space2

It is therefore key that educational performance requirements are an input into the visionary brief of a project. This responsibility rests on educational and academic experts. Briefing processes must be designed in order to accommodate for this and it is particularly important to provide this input in the early stages of visionary and functional briefing. Architects and building consultants will then work (like hardware developers) on design solutions that align with the educational performance requirements. Most likely this is an iterative process and it can be anticipated that the roles between the soft ware and hardware developers might overlap to some degree, but it is central to make sure that both groups are at the table from the very early stages. The educational performance requirement as articulated by the educational experts is one of the driving inputs into the project; not just implicitly assumed by the hardware developers.

Contemporary Educational Concepts Fundamental to Visionary Briefing

There is limited research on how physical space impacts on learning in higher education.3 It is therefore difficult to use evidence-based design principles in the visionary briefing process, and so an alternative educational theory-driven approach to learning space design is proposed here.

Independent of a specific learning theory, there are at least three principles that are common property in the current global discourse driving curriculum development in higher education:

Figure 2.2

The process of creating an interface specification; soft ware and hardware alignment

- • Dialogue: learning is an active process. Learners need to be engaged in conversations between themselves as well as between teacher and individual learners.

- • Visualisation: to access and build on previous knowledge and experience. The ability to visualise, articulate and verbalise previous knowledge and experience is therefore important.

- • Peer-to-peer learning/collaborative learning: there is good evidence that peer-to-peer learning enhances and enriches the individual learning experience. Students may also reach a deeper understanding with the help of peers rather than studying alone.

These three principles (or others, as long as they are derived from educational theory) can function as a first step in interpreting and communicating the underlying research in education to developers of physical learning spaces. Curriculum developers must in simple and concrete terms create the ‘interface specification’ of a curriculum and the kinds of learning space that are needed. The designers (the hardware developers) of learning spaces must be able to clearly understand such principles in order to translate them into a proper building programme and design.

The Networked Learning Landscape

The networked learning landscape model4 used the idea of a learning landscape5 combined with the new technology enabled opportunities for learning in four scales of settings in which particular kinds of learning activities can be organised: classroom, building, campus and city (the integration into the overall urban landscape). The model is a framework to get a better overview of different kinds of learning spaces and how they interconnect6 (see Figure 2.3).

A specific curriculum oft en requires more than one kind of space and it is therefore important to be aware of how spaces in the networked learning landscape are interconnected and can be mutually supportive. The model helps us to understand and analyse the scope of several projects presented in the literature,8 many of which tend to have too limited a focus on only the spaces between classrooms within a building, or on classroom scale alone, with no discussion of how such spaces interconnect across scales and constitute a networked learning landscape.

Figure 2.3

The networked learning landscape7

Four Common Diseases to Avoid in Developing New Physical Learning Spaces

As stated earlier, all physical learning spaces must always be analysed, evaluated and developed in order to align with a current or emerging curriculum. But if we do not pay proper attention to this central message, we might be affected by diseases. The causes of the diseases are the same: lack of access to, and understanding of, underlying educational theories, and lack of recognition of scales and their interconnection.

1. The Power of Un-Surfaced Underlying Assumptions of Learning

No, or too few, ‘soft ware developers’ are involved in the project in early stages or get involved too late. What constitutes contemporary and emerging curricula is therefore left to the designers only or other stakeholders from the client organisation – not primarily involved in education. Their underlying assumptions on learning will then drive and define the educational framing of the project. Consequently – unfortunately – we can see many new projects around the world simply reflecting old-time curricula; the new spaces are already at inauguration ‘museums’ in terms of the design of learning spaces reflecting the history of education rather than the future. This is particularly evident on the classroom scale.

The solution to this disease is: involve software developers in very early briefing stages.

2. Methodological Fetishism

This disease is an obsession with educational methods. A clear symptom and indication of this disease is when universities are marketing their educational strategies via specific methods, such as a university or a specific school in a university defining its offering as a Team-Based Learning (TBL) school or a Problem-Based Learning (PBL) school.

More and more contemporary discussion is moving towards a blended approach to curriculum development, meaning that a building must be able to accommodate more than one specific method. It is therefore critical to avoid situations where an obsession with specific prescriptive teaching methods is driving the building programme, rather than more general principles underlying these methods.

It is a clear responsibility for the software developers to avoid this disease in the visionary stages of briefing and base the educational vision of educational theories rather than individual methods.

3. ‘What’s New on the Educational Catwalk?’

The next disease is closely related to methodological fetishism, namely the sensitivity to the latest of the educational trends. Many schools are trying to keep up-to-date with contemporary education, which is of course honourable. This might, however, become a problem, particularly from a building perspective, if the different ‘seasons on the educational catwalk’ on international conferences will drive specific schools’ curricula.

The vaccine for this particular disease is to base the building programme on specific educational theoretical principles – as above – instead of prescriptive requirements for individual methods. Principles based on contemporary educational theory change at a much slower pace compared with new ‘methods of the educational catwalk’. Many such methods tend to be rather short-lived fads.

4. Lack of Integration between Scales – Isolationism

In some projects the shell of a building is given far more attention and focus than the inside, sometimes to communicate the vision and aspiration of a university. Without any doubt this is one important aspect of developing new buildings. To recognise the interconnection between the four scales of a building and make sure that a specific vision cascades down to the remaining three scales is strongly encouraged. It is important to avoid developing new buildings that look innovative from the outside, just to be aligned with old curriculum models and ideas about learning on the inside.

Innovation and development of the shape and form of a building cannot be isolated to the ‘shell’ scale, but must instead be integrated with the other three scales.

Conclusion

In the device industry, hardware must be compatible with software in order to create new functional products that are successful in the market.

Similarly, in buildings, physical learning spaces must align with contemporary and emerging curricula in order to be successful for teaching and learning in universities.

Ultimately, software developers (the curriculum developers) need to be much more actively involved in developing physical learning spaces together with hardware developers (the designers of the spaces) in an iterative and creative process with a clear curriculum alignment in mind.